The objective of this study was to perform an epidemiological analysis of patients presented to the Musculoskeletal Tumors Committee of a reference hospital.

Material and methodA retrospective analysis of patients with sarcomas treated in a reference Sarcoma Unit between 2009 and 2022 was carried out.

ResultsA total of 1978 patients were analysed, of which 1477 (74.67%) were diagnosed as sarcomas. They were divided into 446 (30.20%) bone tumours and 1.031 (69.80%) soft tissue tumours. The most common benign bone tumour was enchondroma (27.23%), giant cell tumour (59.21%) was the most common tumour of intermediate malignancy and the malignant one was osteosarcoma (24.78%). The most frequently observed benign soft tissue tumour was lipoma (50.74%), the atypical lipomatous tumour (53.25%) was the most frequent tumour of intermediate malignancy and the malignant one was sarcoma of uncertain differentiation (38.10%).

ConclusionOur study represents the first work on the epidemiology of sarcomas and other musculoskeletal tumours in our country, being very useful to adapt the resources destined for their diagnosis and treatment.

El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar un análisis epidemiológico de los pacientes presentados en el Comité de Tumores Musculoesqueléticos de un hospital de referencia.

Material y métodoSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de pacientes con sarcomas tratados en una unidad de sarcomas de referencia entre 2009 y 2022.

ResultadosSe analizaron un total de 1.978 pacientes, de los cuales 1.477 (74,67%) fueron diagnosticados como tumores musculoesqueléticos. Se dividieron en 446 (30,20%) tumores óseos y 1.031 (69,80%) tumores de partes blandas. El tumor óseo benigno más frecuente fue el encondroma (27,23%), el tumor de células gigantes (59,21%) fue el tumor de malignidad intermedia más frecuente y el maligno fue el osteosarcoma (24,78%). Dentro de los tumores de partes blandas, los más frecuentes en nuestra serie según el grado de malignidad fueron el lipoma (50,74%) como tumor benigno, el tumor lipomatoso atípico (53,25%) como tumor de malignidad intermedia y el sarcoma de diferenciación incierta (38,10%) como tumor maligno.

ConclusiónNuestro estudio supone el primer trabajo sobre epidemiología de los sarcomas y otros tumores musculoesqueléticos en nuestro país, siendo de gran utilidad para adaptar los recursos destinados a su diagnóstico y tratamiento.

Sarcoma and other musculoskeletal tumours are rare diseases that should be treated in referral centres in order to improve their diagnosis and treatment.1

Knowledge of the epidemiological characteristics and geographical distribution of these tumours is very important for appropriate clinical suspicion and for optimising the referral of these patients to specialist units.1,2 However, few studies have analysed these characteristics, and there is no descriptive epidemiological study based on the Spanish population.

The aim of our study was to carry out an epidemiological analysis of the patients presented to the Sarcoma and Musculoskeletal Tumour Committee of a referral hospital.

Material and methodsStudy designWe conducted a retrospective study of patients aged 15 years or older presented to the Musculoskeletal Tumour Committee of the Hospital Universitario i Politécnico La Fe de Valencia (HUP La Fe), accredited as a CSUR (national unit of expertise) for sarcoma and other musculoskeletal tumours (Date of accreditation: 15-12-2018), in the period between 01/09/2009 and 31/12/2022. Patients under 15 years of age were excluded as they are presented to different committees.

The patients were divided into 4 groups according to diagnosis: musculoskeletal tumours, metastases, non-musculoskeletal tumours, and non-tumour involvement. Musculoskeletal tumours were subclassified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2020 classification3 into bone or soft tissue, benign histology, intermediate malignancy (locally aggressive, but with low metastatic potential), or malignant. Metastases were grouped according to their primary. The histopathological diagnosis was determined after review by 2 pathologists specialising in bone and soft tissue tumours.

The following variables were collected for each tumour subtype: frequency, age, sex, anatomical location and histopathological diagnosis.

Statistical analysisSPSS® (version 24.0; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis; a descriptive analysis of the variables was performed to determine frequencies and percentages.

Ethical aspectsThis work was carried out in accordance with the European recommendations for good clinical practice and the principles of the Helsinki declaration of the World Medical Assembly (WMA) revised in 2013 for clinical studies involving human subjects. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution, whose registration number is 2023-752-1.

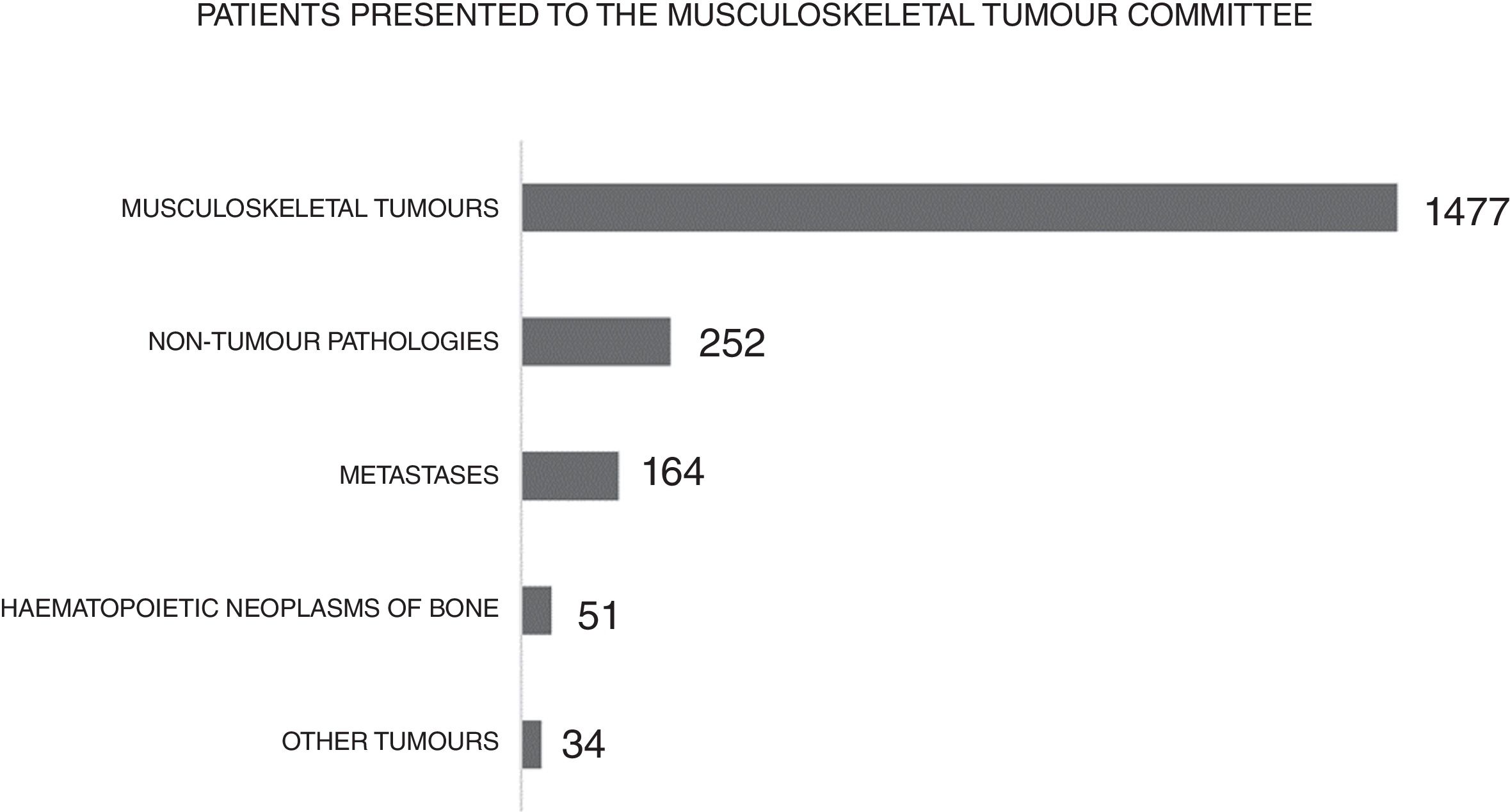

ResultsA total of 1978 patients presented to the Musculoskeletal Tumour Committee of the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe between 2009 and 2022 were studied. Of the total number of patients, 74.77% were diagnosed with musculoskeletal tumours – which were divided into 30.20% bone tumours and 69.80% soft tissue tumours – 1.72% non-musculoskeletal tumours (melanomas, carcinomas, neural tumours, etc.), 8.29% metastases (melanomas, carcinomas, neural tumours, etc.), 8.29% metastatic tumours (melanomas, carcinomas, carcinomas, neural tumours, etc.), 8.29% metastases, 2.58% haematopoietic bone neoplasms and, finally, 12.74% non-tumour conditions (osteomyelitis, arteriovenous malformations, cysts, arthrosis, etc.) (Fig. 1).

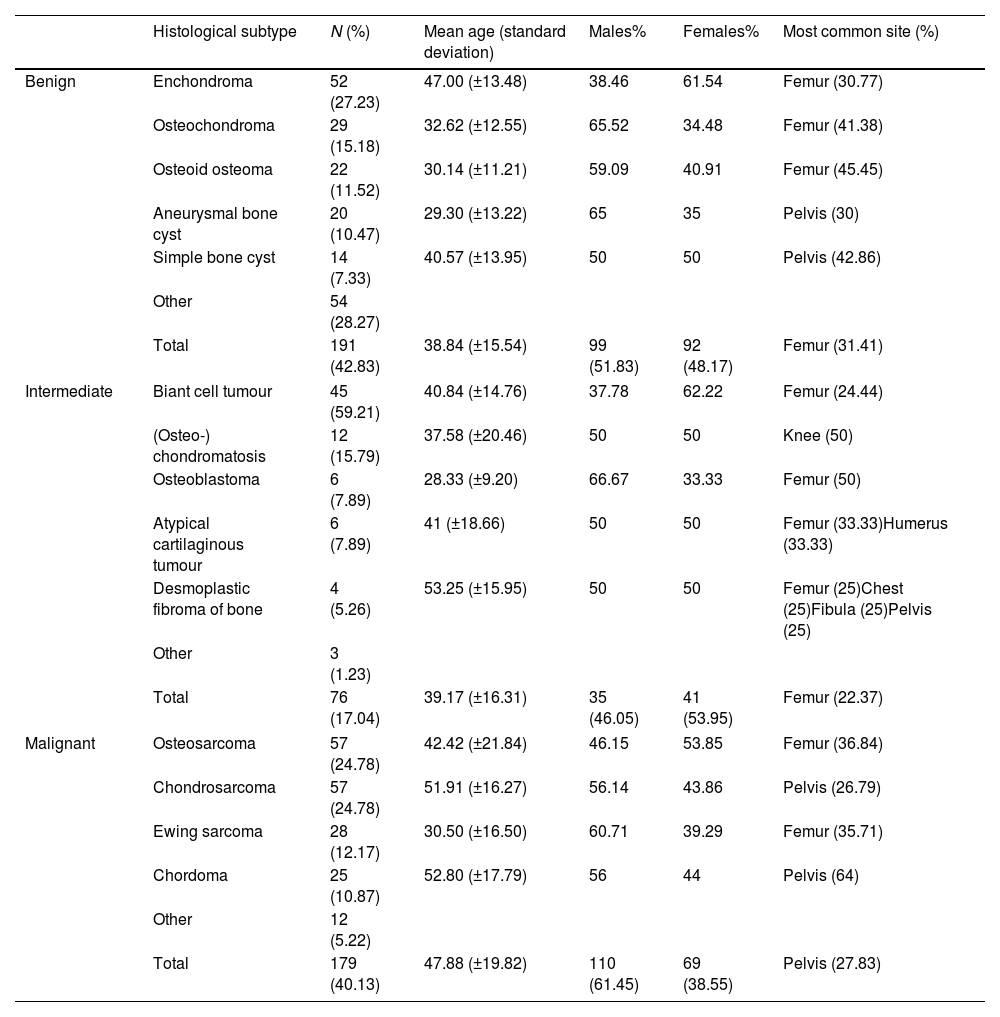

According to the classification, 42.83% of the bone tumours were benign, 17.04% were intermediate malignant, and 40.13% were malignant.

In this series, the most common benign bone tumours were enchondroma (27.23%), osteochondroma (15.18%), osteoid osteoma (11.52%), aneurysmal bone cyst (10.47%), and simple bone cyst (7.33%). Enchondroma was most frequently located in the femur in 30.77% of patients; with a mean age of 47±13.48 years and divided into 37.04% males and 62.96% females.

Among intermediate malignant bone tumours, the most commonly found were giant cell tumour (59.21%), osteochondromatosis (15.79%), osteoblastoma (7.89%), atypical cartilaginous tumour (7.89%), and desmoplastic bone fibroma (5.26%). Giant cell tumour was most commonly found in the femur in 30.77% of patients. It was found in 37.78% of males and 62.22% of females; with a mean age of 40.84±14.76 years.

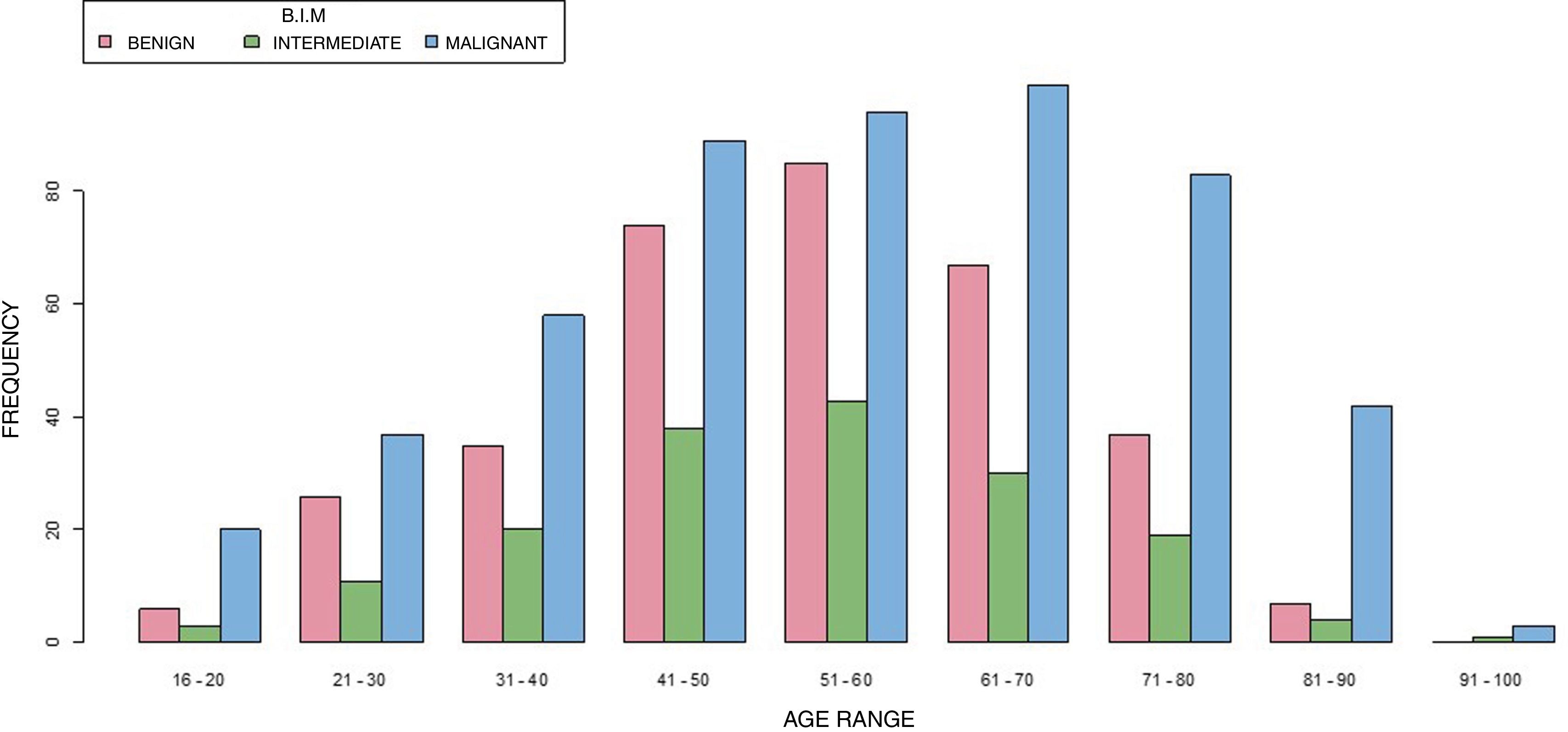

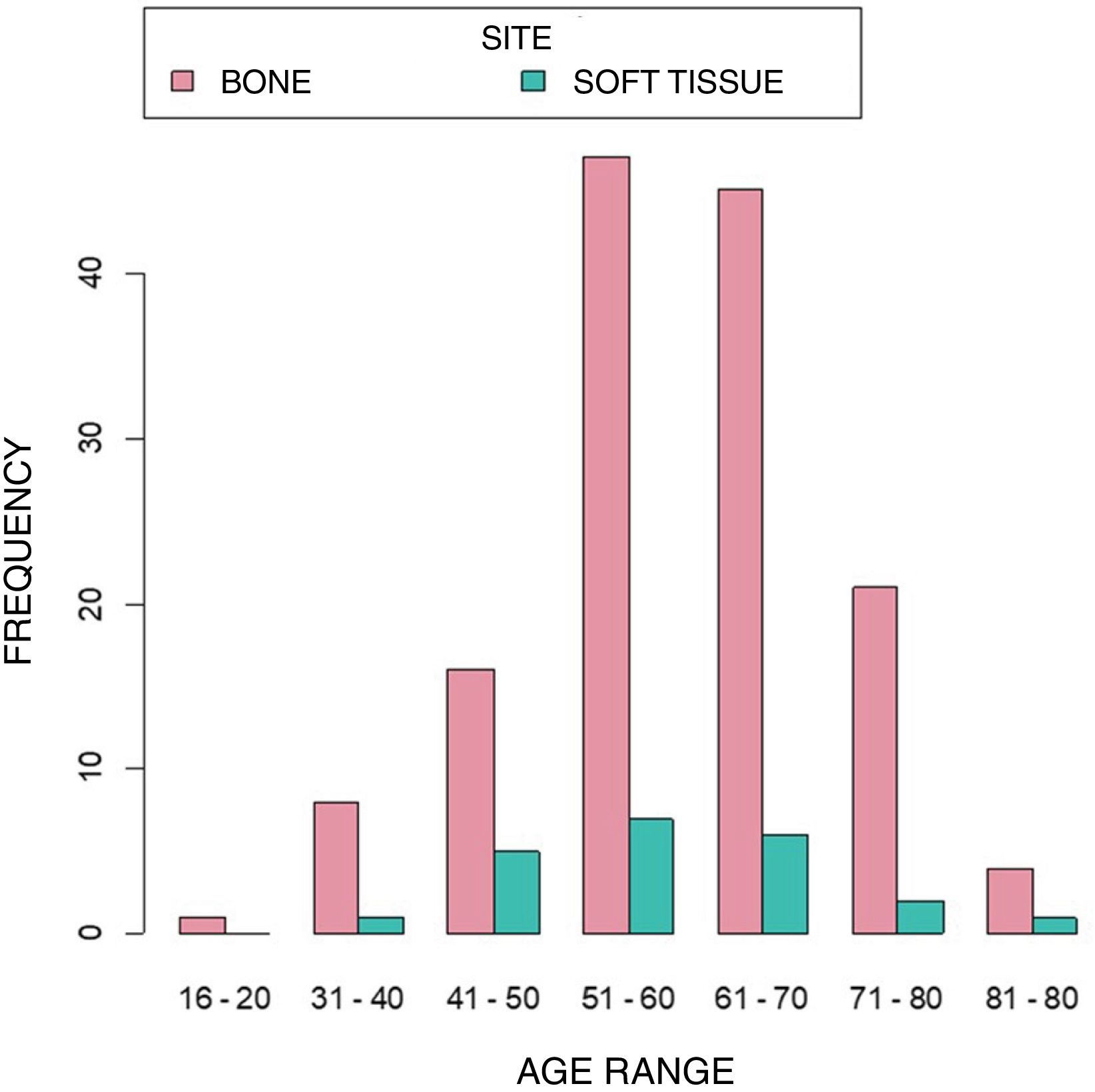

Of the total number of malignant bone tumours, the most common were osteosarcoma (24.78%), chondrosarcoma (24.78%), Ewing sarcoma (12.17%), and chordoma (10.87%). In osteosarcoma, the femur was the predominant site in 21, in 36.84% of patients, affecting 46.15% of males and 53.85% of females, with a mean age of 42.42±21.84 years. In contrast, the most common site of chondrosarcoma was the pelvis in 26.79% of patients. This tumour affected 56.14% of males and 43.86% of females; with a mean age of 51.91±16.27 years. The characteristics of the rest of the subtypes are shown in Table 1. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of bone tumours according to age range, and Fig. 3 shows the distribution according to sex.

Classification of bone tumours according to grade of malignancy.

| Histological subtype | N (%) | Mean age (standard deviation) | Males% | Females% | Most common site (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Enchondroma | 52 (27.23) | 47.00 (±13.48) | 38.46 | 61.54 | Femur (30.77) |

| Osteochondroma | 29 (15.18) | 32.62 (±12.55) | 65.52 | 34.48 | Femur (41.38) | |

| Osteoid osteoma | 22 (11.52) | 30.14 (±11.21) | 59.09 | 40.91 | Femur (45.45) | |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | 20 (10.47) | 29.30 (±13.22) | 65 | 35 | Pelvis (30) | |

| Simple bone cyst | 14 (7.33) | 40.57 (±13.95) | 50 | 50 | Pelvis (42.86) | |

| Other | 54 (28.27) | |||||

| Total | 191 (42.83) | 38.84 (±15.54) | 99 (51.83) | 92 (48.17) | Femur (31.41) | |

| Intermediate | Biant cell tumour | 45 (59.21) | 40.84 (±14.76) | 37.78 | 62.22 | Femur (24.44) |

| (Osteo-) chondromatosis | 12 (15.79) | 37.58 (±20.46) | 50 | 50 | Knee (50) | |

| Osteoblastoma | 6 (7.89) | 28.33 (±9.20) | 66.67 | 33.33 | Femur (50) | |

| Atypical cartilaginous tumour | 6 (7.89) | 41 (±18.66) | 50 | 50 | Femur (33.33)Humerus (33.33) | |

| Desmoplastic fibroma of bone | 4 (5.26) | 53.25 (±15.95) | 50 | 50 | Femur (25)Chest (25)Fibula (25)Pelvis (25) | |

| Other | 3 (1.23) | |||||

| Total | 76 (17.04) | 39.17 (±16.31) | 35 (46.05) | 41 (53.95) | Femur (22.37) | |

| Malignant | Osteosarcoma | 57 (24.78) | 42.42 (±21.84) | 46.15 | 53.85 | Femur (36.84) |

| Chondrosarcoma | 57 (24.78) | 51.91 (±16.27) | 56.14 | 43.86 | Pelvis (26.79) | |

| Ewing sarcoma | 28 (12.17) | 30.50 (±16.50) | 60.71 | 39.29 | Femur (35.71) | |

| Chordoma | 25 (10.87) | 52.80 (±17.79) | 56 | 44 | Pelvis (64) | |

| Other | 12 (5.22) | |||||

| Total | 179 (40.13) | 47.88 (±19.82) | 110 (61.45) | 69 (38.55) | Pelvis (27.83) | |

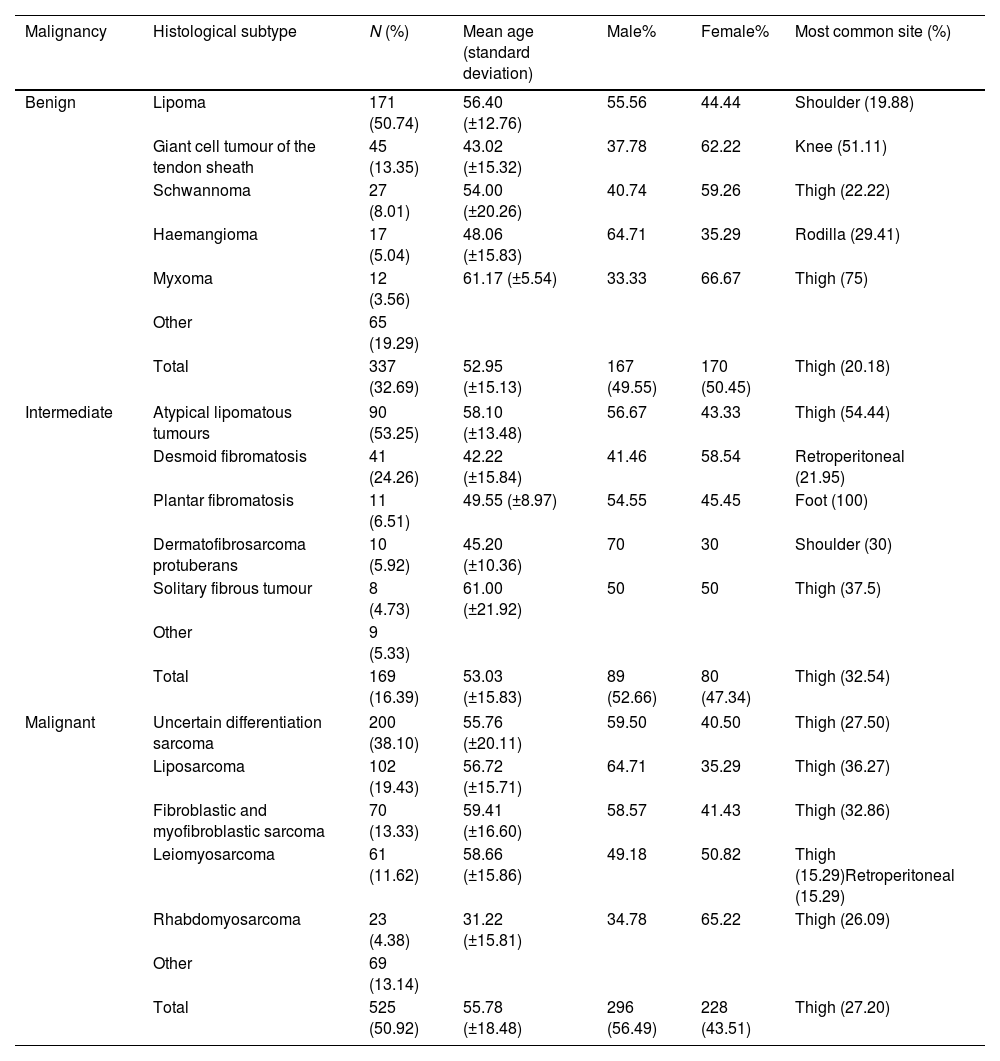

Soft tissue tumours were grouped according to grade of malignancy. Of the total number of soft tissue tumours, 32.69% were benign, 16.39% were intermediate malignant, and 50.92% were malignant.

The most common benign tumours were lipoma (50.74%), giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath (13.35%), schwannoma (8.01%), haemangioma (5.04%), and myxoma (3.56%). Lipoma was most commonly found in the shoulder in 19.88% of patients. The mean age of collected lipomas was 56.40±12.76 years; affecting 55.56% of males and 44.44% of females.

The most common intermediate malignancies were atypical lipomatous tumour (53.25%), desmoid-type fibromatosis (24.26%), plantar fibromatosis (6.51%), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (5.92%), and solitary fibrous tumour (4.73%). All are classified as intermediate malignant tumours, the first 3 being locally aggressive and the last 2 rarely metastatic. Atypical lipomatous tumours were located in the thigh in 54.44% of patients, with a mean age of 58.10±13.448 years, 56.67% in males and 43.33% in females.

Among the malignant soft tissue tumours, sarcoma of uncertain differentiation (38.10%), liposarcoma (19.43%) (subdivided into 48.45% myxoid liposarcoma, 24.74% dedifferentiated liposarcoma, 13,40% in well-differentiated liposarcomas, 12.37% pleomorphic liposarcoma, and 1.03% sclerosing liposarcoma), fibroblastic and myofibroblastic sarcoma (13.33%), leiomyosarcoma (11.62%), and rhabdomyosarcoma (4.38%). Sarcoma of uncertain differentiation at 38.10% were the most common, mainly located in the thigh (27.50%), the mean age of these patients being 55.76±20.11 years; affecting 59.50% of males and 40.50% of females.

Sarcoma of uncertain differentiation, which include those sarcomas that do not show a clear pattern of differentiation towards a specific tissue type (undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, synovial sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, myxoid chondrosarcoma, etc.); they are mainly subdivided into undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (47.5%), synovial sarcoma (20%), extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma (7%), extraskeletal osteosarcoma (7%), and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (5.5%). The characteristics of the remaining subtypes are shown in Table 2. Fig. 4 shows the distribution of soft tissue tumours by age range and Fig. 5 by sex.

Classification of soft tissue tumours according to grade of malignancy.

| Malignancy | Histological subtype | N (%) | Mean age (standard deviation) | Male% | Female% | Most common site (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | Lipoma | 171 (50.74) | 56.40 (±12.76) | 55.56 | 44.44 | Shoulder (19.88) |

| Giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath | 45 (13.35) | 43.02 (±15.32) | 37.78 | 62.22 | Knee (51.11) | |

| Schwannoma | 27 (8.01) | 54.00 (±20.26) | 40.74 | 59.26 | Thigh (22.22) | |

| Haemangioma | 17 (5.04) | 48.06 (±15.83) | 64.71 | 35.29 | Rodilla (29.41) | |

| Myxoma | 12 (3.56) | 61.17 (±5.54) | 33.33 | 66.67 | Thigh (75) | |

| Other | 65 (19.29) | |||||

| Total | 337 (32.69) | 52.95 (±15.13) | 167 (49.55) | 170 (50.45) | Thigh (20.18) | |

| Intermediate | Atypical lipomatous tumours | 90 (53.25) | 58.10 (±13.48) | 56.67 | 43.33 | Thigh (54.44) |

| Desmoid fibromatosis | 41 (24.26) | 42.22 (±15.84) | 41.46 | 58.54 | Retroperitoneal (21.95) | |

| Plantar fibromatosis | 11 (6.51) | 49.55 (±8.97) | 54.55 | 45.45 | Foot (100) | |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | 10 (5.92) | 45.20 (±10.36) | 70 | 30 | Shoulder (30) | |

| Solitary fibrous tumour | 8 (4.73) | 61.00 (±21.92) | 50 | 50 | Thigh (37.5) | |

| Other | 9 (5.33) | |||||

| Total | 169 (16.39) | 53.03 (±15.83) | 89 (52.66) | 80 (47.34) | Thigh (32.54) | |

| Malignant | Uncertain differentiation sarcoma | 200 (38.10) | 55.76 (±20.11) | 59.50 | 40.50 | Thigh (27.50) |

| Liposarcoma | 102 (19.43) | 56.72 (±15.71) | 64.71 | 35.29 | Thigh (36.27) | |

| Fibroblastic and myofibroblastic sarcoma | 70 (13.33) | 59.41 (±16.60) | 58.57 | 41.43 | Thigh (32.86) | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 61 (11.62) | 58.66 (±15.86) | 49.18 | 50.82 | Thigh (15.29)Retroperitoneal (15.29) | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 23 (4.38) | 31.22 (±15.81) | 34.78 | 65.22 | Thigh (26.09) | |

| Other | 69 (13.14) | |||||

| Total | 525 (50.92) | 55.78 (±18.48) | 296 (56.49) | 228 (43.51) | Thigh (27.20) | |

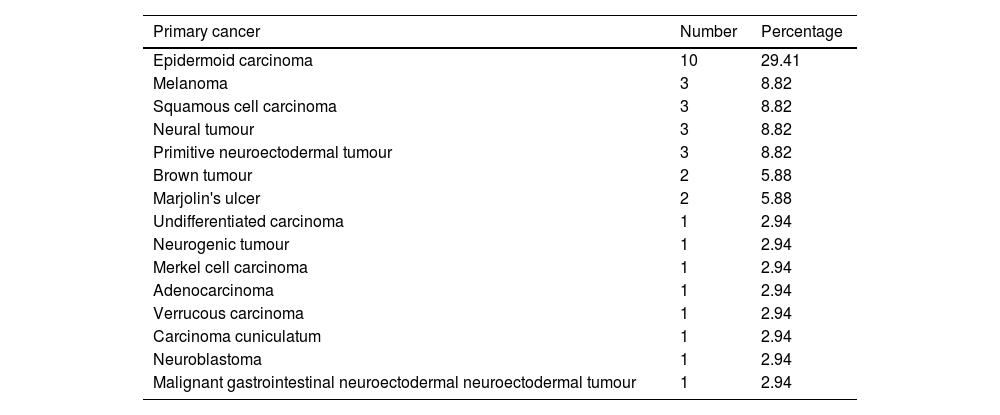

Of the patients presented to the Committee, 34 were diagnosed with tumours of histology other than sarcoma, the most common being epidermoid carcinoma (29.41%), followed by melanoma (8.82%), and squamous cell carcinoma (8.82%) (Table 3). The most common sites for epidermoid carcinoma were the foot and thigh, at 40% of the cases. The mean age of epidermoid carcinoma was 69.60±17.87 years; 60% in males and 40% in females.

Tumours of aetiology other than sarcoma.

| Primary cancer | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermoid carcinoma | 10 | 29.41 |

| Melanoma | 3 | 8.82 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3 | 8.82 |

| Neural tumour | 3 | 8.82 |

| Primitive neuroectodermal tumour | 3 | 8.82 |

| Brown tumour | 2 | 5.88 |

| Marjolin's ulcer | 2 | 5.88 |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 1 | 2.94 |

| Neurogenic tumour | 1 | 2.94 |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 1 | 2.94 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 2.94 |

| Verrucous carcinoma | 1 | 2.94 |

| Carcinoma cuniculatum | 1 | 2.94 |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 | 2.94 |

| Malignant gastrointestinal neuroectodermal neuroectodermal tumour | 1 | 2.94 |

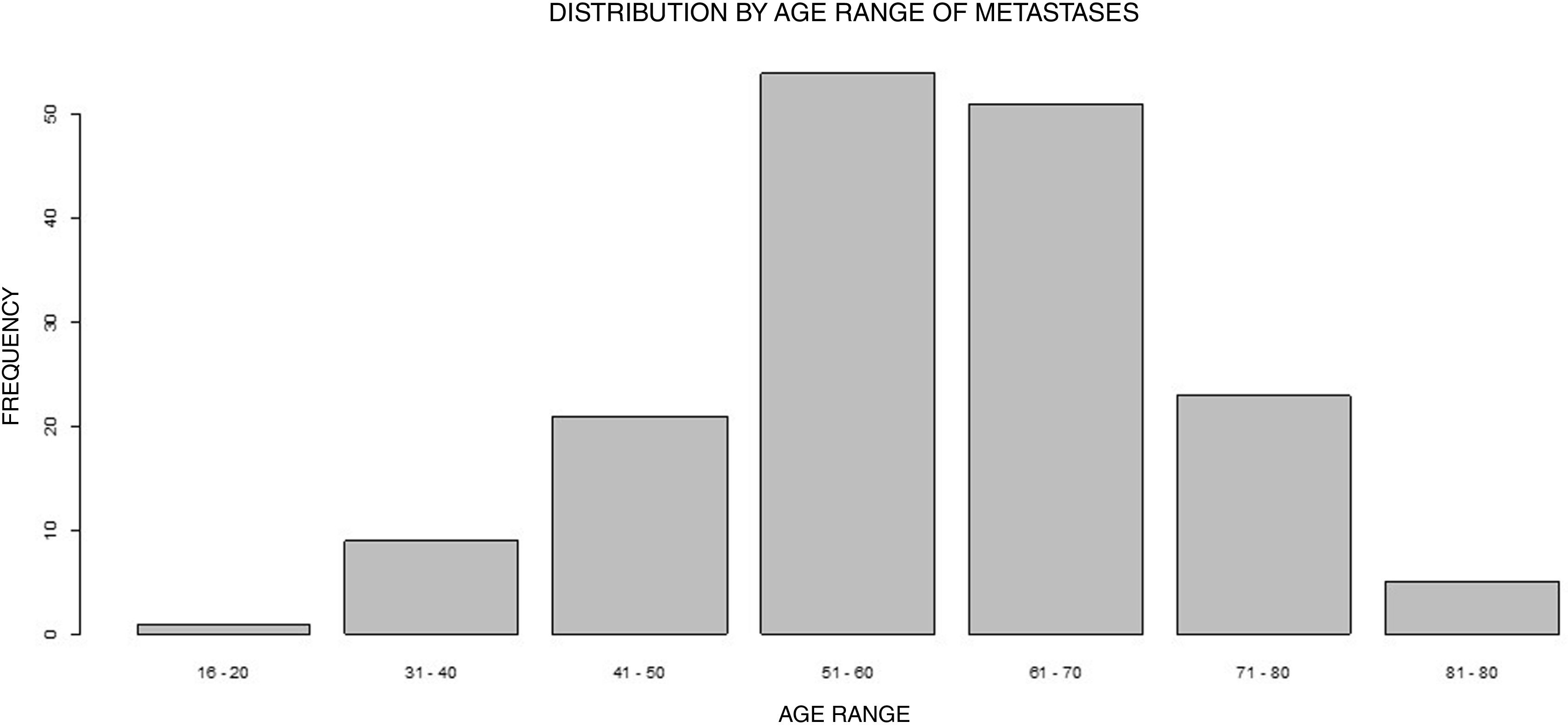

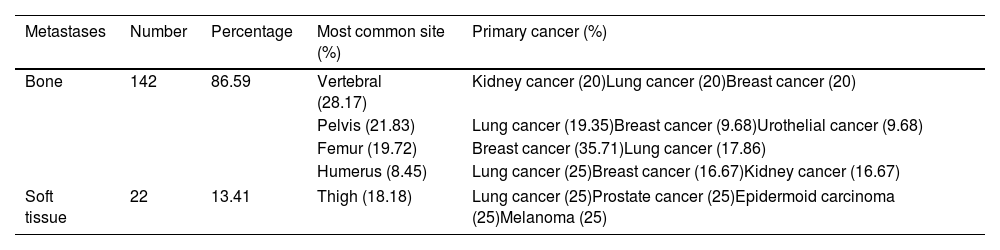

Of the 162 patients with metastases, 86.59% were located in bone and 13.41% in soft tissue (Table 4). The most common sites for bone metastases were the vertebrae (17%) and the thigh (18.18%) in soft tissue. The primaries of the metastases were lung cancer (24.69%), breast cancer (19.75%), and kidney cancer (10.49%). For lung cancer, the predominant site was vertebral column (20%). The mean age of the cases with lung cancer metastasis was 60.35±9.77 years. Of those affected, 65% were male and 35% were female.

Metastases of other tumours in bone and soft tissue.

| Metastases | Number | Percentage | Most common site (%) | Primary cancer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | 142 | 86.59 | Vertebral (28.17) | Kidney cancer (20)Lung cancer (20)Breast cancer (20) |

| Pelvis (21.83) | Lung cancer (19.35)Breast cancer (9.68)Urothelial cancer (9.68) | |||

| Femur (19.72) | Breast cancer (35.71)Lung cancer (17.86) | |||

| Humerus (8.45) | Lung cancer (25)Breast cancer (16.67)Kidney cancer (16.67) | |||

| Soft tissue | 22 | 13.41 | Thigh (18.18) | Lung cancer (25)Prostate cancer (25)Epidermoid carcinoma (25)Melanoma (25) |

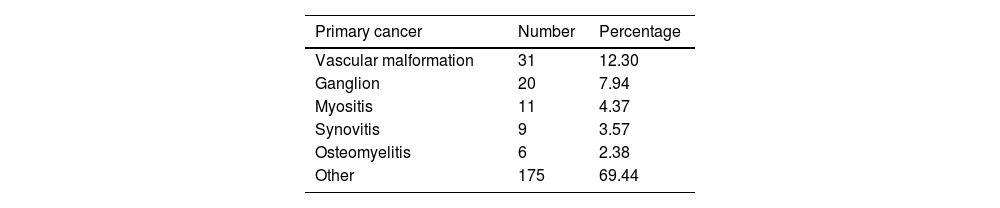

Two hundred and fifty-two patients who were presented to the Committee and were not diagnosed with musculoskeletal tumours on individual examination. Of note were vascular malformation (12.30%), ganglion (7.94%), myositis (4.37%), pigmented non-villonodular synovitis (3.57%), and osteomyelitis (2.38%) (Table 5). Vascular malformations were found in the thigh in 22.58% of the patients; with a mean age of 39.48±15.87 years and a gender distribution of 29.03% in males and 70.97% in females.

DiscussionSarcoma and musculoskeletal tumours should be treated in referral centres to improve their multidisciplinary management.4 One of the reasons for the poorer prognosis of these patients is the late diagnosis of these tumours,1,2 and therefore knowing their epidemiology allows us to guide the distribution of resources and optimise their diagnosis and referral to referral centres.

Currently, there are a limited number of studies showing the distribution of bone and soft tissue tumours in different countries; demographic data have only been published for specific regions such as Switzerland, Croatia, and Turkey.5–7 We did not find any studies presenting the epidemiology of musculoskeletal tumours in Spain, this being the first to date.

The age distribution of musculoskeletal tumours varies according to their bone or mesenchymal origin. Regarding bone tumours, in this study benign tumours reached their highest incidence in the age range 21–50 years, whereas malignant tumours were mainly concentrated in the 4th decade and in the 61–70 age range, being more frequent around the age of 70 years. Öztürk et al. (2019)8 and Dabak (2014) describe a peak incidence in the age range 0–20 years in bone tumours; we would highlight that this trend is not shown in our work, because patients younger than 15 years were not included as they are assessed in a different committee.

For soft tissue tumours, we describe a progressive increase in incidence with age for both benign and malignant tumours, peaking between the 6th and 7th decade of life. After this peak, their frequency gradually decreases. Series published in Turkey8,9 describe similar age distributions for soft tissue tumours.

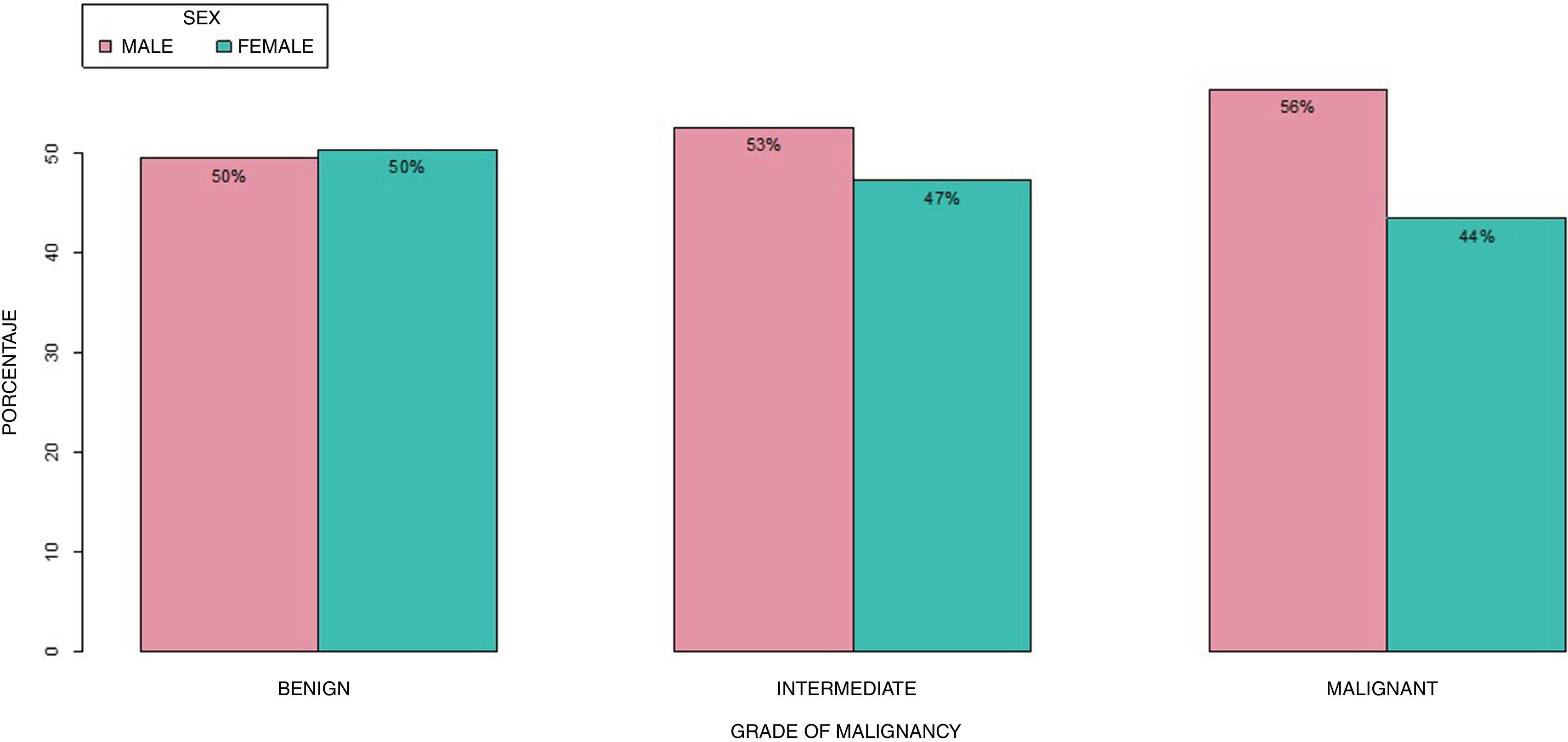

Similar to other studies, some male predominance is described for both benign and malignant bone tumours (Table 1) and malignant soft tissue tumours (Table 2).5,7–10 However, the female sex slightly predominates in benign soft tissue tumours in this work. This finding is, however, difficult to compare with works such as Öztürk et al. Öztürk et al. (2019)8 and Sevimli (2017),5 as these authors analyse sex globally in bone or soft tissue tumours; regardless of their grade of benignity or malignancy.

In this series, benign bone tumours were most commonly located in the femur, humerus, and tibia, coinciding with studies previously published in other regions.5,6,9 Malignant bone tumours were predominantly located in the pelvis and around the hip joint (Table 1), similar to that described by Sevimli (2017)5 and Dabak (2014).9 Soft tissue tumours, on the other hand, were located in the lower limbs, with the thigh being the most common site (Table 2). Some studies report the hand and wrist as the main region for benign soft tissue tumours,5,9 unlike this series, probably because many benign tumours are not referred to referral centres. Bone metastases were mainly located in the spine, followed by the pelvis and femur (Table 4) as described in the literature.4

With regard to benign bone tumours, we compared our series with studies from Turkey,5,8,9 Mexico,6 and Croatia.10 These studies present osteochondroma as the most frequently reported benign bone tumour. However, in this study, as in the series of patients by Yücetürk (2011),11 who also studied patients presented to their multidisciplinary committee, enchondroma was the most common, followed by osteochondroma. This may be because enchondroma causes more diagnostic uncertainty in low-grade chondrosarcoma than osteochondroma and is more frequently referred to these referral centres.

The most common malignant bone tumours were osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma, followed by haematological bone neoplasms. This series is consistent with the work of Baena-Ocampo et al. (2009),6 Öztürk et al. (2019),8 Dabak (2014),9 Bergovec et al. (2015),10 Yücetürk (2011),11 and Blackwell et al. (2005),12 highlighting that in the work by Kóllar et al. (2019)7 in Switzerland and Sevimli et al. (2017)5 in Turkey, chondrosarcoma is the most frequent, followed by osteosarcoma, possibly related to geographical differences.

In this work, the most common benign soft tissue tumour was lipoma, accounting for more than half of all soft tissue tumours, followed by giant cell tumour of the tendon sheath. Some authors5,9 report the predominance of ganglion (cystic hygroma), while others such as Öztürk et al. (2019)8 agree with the predominance of lipoma as the most common benign soft tissue tumour, albeit with a lower representation. For their part, Yücetürk (2011)11 report vascular tumours as the most common tumours in their series. Again, this suggests that although ganglion is probably the most common, their benignity and the familiarity of general orthopaedic surgeons with the management of this pathology means that referrals to a referral centre such as ours are infrequent.

The most common malignant soft tissue sarcomas in our series were liposarcoma (19.43%) and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (17.5%), data similar to other published studies.5,7–9,11

In our series, lung, breast, and kidney tumours are described as the most common primaries, consistent with previous studies.8,9,11 These authors describe metastases from unknown primary tumours as the most common, although in this study this was a sporadic finding in 4 patients.

The approach to management of metastases is undergoing a paradigm shift, and we must consider the possibility of curative treatment in patients with single or even oligometastatic metastases. Consequently, referral units will have to adapt their resources to deal with this new scenario.

The main limitations of our study are, firstly, not having included patients under 15 years of age and, consequently, the lower incidence of tumours common in children, such as osteosarcoma. On the other hand, most of the patients referred were from our Autonomous Community, with different incidences in the different regions of Spain. Finally, the incidence of some benign tumours may be biased due to their treatment in other centres of origin.

In conclusion, our epidemiological data agree in most aspects with those published in studies carried out in other areas. However, multicentre studies at a national level would be very useful to understand the epidemiology of these tumours in our country, and to be able to adapt resources to optimise their treatment.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the European recommendations for good clinical practice and the tenets of the World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2013 for clinical studies in humans. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution, whose registration number is 2023-752-1.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.