Osteoporosis represents a public health problem that can be prevented and treated early through health education. Over time, screening techniques, diagnosis and treatments even conservative and surgical, have improved.

Through this publication we want to highlight the importance of the medical and orthopaedic management of these fractures, describing the benefit of diet and physical exercise as the protagonists of conservative treatment but above all its indications and contraindications, emphasising the limitations of exercise in a vertebral osteoporotic fracture. The different orthoses prescriptions are also highlighted.

La osteoporosis representa un problema de salud pública que se puede prevenir y tratar de forma precoz mediante la educación sanitaria. A través de los tiempos se han mejorado las técnicas de cribado, el diagnóstico y, por supuesto, los tratamientos indicados, tanto conservadores como quirúrgicos.

Mediante esta publicación se quiere resaltar la importancia del manejo rehabilitador y ortopédico de estas fracturas, describir el beneficio de la dieta y el ejercicio físico como los protagonistas del tratamiento conservador, pero, sobre todo, sus indicaciones y contraindicaciones, con énfasis en las limitaciones ante una fractura vertebral osteoporótica. Se destaca también el uso de ortesis y sus prescripciones.

Osteoporosis (OP) is considered a public health problem, as outlined in Bone Health and Osteoporosis.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of diseases, osteoporosis is defined as a bone mineral density (BMD) at the hip or lumbar spine that is less than or equal to 2.5 standard deviations below the young adult mean BMD. Osteoporosis is a risk factor for fracture,1 although most vertebral fractures are initially clinically silent, they are often associated with symptoms of pain, disability, deformity, and high mortality rate.1 Posture change and/or kyphotic attitude is often the most striking effect in patients and has significant psychological impact2; fracture risk and decreased BMD increase exponentially with age.

In the process of bone remodelling old bone is continually removed and replaced with new bone; when this balance is disturbed, more bone is removed than replaced resulting in disordered skeletal architecture and an increase in fracture risk,1 all of which is usually caused by menopause and ageing.

It is recommended that people with fractures or clinical conditions associated with an elevated fracture risk be referred to bone metabolism specialists or hospital units for management.3 Peak bone mass is largely determined by genetic, nutritional, physical activity, and health factors.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) first published the guideline in 1999 that recommends a comprehensive approach to the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, which includes:

- -

Detailed medical history.

- -

Physical examination to identify osteoarticular pain and muscle lesions.

- -

BMD assessment.

- -

Vertebral imaging to diagnose vertebral fractures.

- -

Fracture risk assessment tool.

- -

Risk factors for falls.

The treatment of vertebral compression fractures can be divided into surgical and non-surgical. Non-surgical treatment options include pain control, relative rest, and back bracing.4 However, population education to prevent future fractures by addressing the underlying cause and recovery of functional mobility is the fundamental cornerstone.5

There are universal recommendations for the treatment of osteoporosis:

- -

Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

- -

Regular exercise.

- -

Muscle strengthening exercise programmes.

- -

Smoking cessation and reduction of alcohol consumption.

- -

Treatment of risk factors for falls.

Supervised exercise rehabilitation programmes constitute one of the most important non-surgical treatments. They can reduce disability and improve agility, strength, posture, and balance, which can reduce the risk of falls and fractures.

Another important aspect to highlight is a differential diagnosis between the muscle and the bone component, hence a cross-sectional study published by Tiftik T et al. in 2023,6 that attempted to identify the relationship between sarcopenia and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women, with a sample of 546 postmenopausal women of whom 222 (40.7%) had OP. Among the parameters related to sarcopenia, grip strength, and anterior thigh muscle thickness were positively associated with lumbar vertebral BMD. The chair stand test was positively associated with femoral neck BMD. Another parameter analysed was grip strength, cases of grip strength<22kg had a 1.6-fold increased risk for OP. In conclusion, they state that sarcopenia and OP can coexist in these patients and that grip strength can be recommended as a predictor of risk for fall and postmenopausal vertebral fractures, given its easy application, reliability, and low cost.6

ExercisesExercise has been proposed as a potential strategy for managing osteoporosis7; however, the magnitude of the benefit of exercise intervention is traditionally perceived as modest at best.

The best estimate is what happens in postmenopausal women who exercise described as:

- -

Those who exercised had, on average, .85% less bone loss than those who did not exercise.

- -

People who participated in combinations of exercise types had, on average, 3.2% less bone loss than those who did not exercise.

In 1993, M.R. Forwood,8 reported sufficient data to demonstrate that moderate to intensive training can bring about modest increases of about 1–3% in bone mineral content in men and premenopausal women.

A consensus process was conducted to develop exercise recommendations for people with osteoporosis or vertebral fractures due to osteoporosis,9 and the panel strongly recommended a multicomponent exercise including resistance and balance training for individuals with osteoporosis or osteoporotic vertebral fracture, under professional supervision in older patients due to associated comorbidities and osteoarticular disease. As recommended in the guidelines and exercises of the Spanish Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SERMEF), https://www.sermef.es.

In the 2018 LIFTMOR trial, a brief programme of high-intensity resistance and impact training was shown to be effective in improving bone density and functional performance in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. It also highlights the importance of effective pain management in vertebral fracture rehabilitation.10

The guidelines for osteoporotic and postmenopausal patients usually recommend exercises of moderate intensity calculated as 1 repetition maximum (RM) which is the maximum weight that a person can lift for a single repetition of a given exercise, and the weight is calculated at 70–80%, 8–15 repetitions, exercises for individual muscle groups that are unlikely to generate the skeletal strain necessary to stimulate an osteogenic response.7,10

By contrast, large multi-joint compound exercises such as the squat and deadlift conducted in weight-bearing positions and involving extensive muscle recruitment have the potential to apply large loads at clinically relevant bone sites such as the spine and the hip, and have shown osteogenic changes.

Regular exercise with muscle loading and strengthening is recommended. However, there is insufficient evidence to quantify the risks of exercise in people with osteoporosis or vertebral fracture because there are few studies involving training and exercise testing in people with osteoporotic vertebral fracture, and therefore certain conditions must be met before indicating training.

The NOF strongly supports lifelong physical activity at all ages, both for the prevention of osteoporosis and for general health.

Recommended exercise includes walking, jogging, Tai Chi, stair climbing, dancing, and tennis. Muscle-strengthening exercise includes resistive exercises, such as yoga, Pilates, and boot camp programmes.1

Rehabilitation and exercise are recognised means of improving function, as well as activities of daily living. Psychosocial factors also greatly affect the functional capacity of the osteoporosis patient who has already suffered fractures. Fall prevention programmes are often multimodal, including balance, functional, and resistance training, and can achieve a 61% reduction in falls that result in fractures.10

Some aspects must be considered when starting a rehabilitation programme in osteoporotic patients:

- -

Age.

- -

Functional status before the fracture.

- -

Psychological and social status.

- -

Nutritional status.

- -

Medication.

Provide training for performing safe movement and safe activities of daily living, including posture, transfers, lifting, and ambulation in older populations with or at high risk for osteoporosis.1

The rehabilitation programme has various objectives:

- -

Prescribe assistive devices to improve balance with mobility.

- -

Correct underlying deficits whenever possible.

- -

Improve posture and balance.

- -

Strengthen muscles to allow a person to rise unassisted from a chair; promote the use of assistive devices to help with ambulation, balance, lifting, and reaching.

- -

Evaluate home environment for risk factors for falls.

Therefore, the latest guidelines recommend aerobic exercise including walking, cycling, stair climbing daily for more than 20min and weight training 2–3 days a week and 2–3 cycles per muscle group, the latter being the most recommended to prevent further bone loss and maintain or improve BMD.19

Patients should be advised to avoid forward bending and exercising with trunk in flexion, especially in combination with twisting, and should start activities of daily living as soon as possible if pain permits.

Effective pain management is critical in the rehabilitation of vertebral fractures, and can be achieved through a variety of physical, pharmacological, and behavioural techniques, taking care that the benefits do not outweigh the risks of side effects, such as disorientation or sedation, which may result in falls.

Back bracingBack bracing is part of the conservative medical treatment of osteoporotic fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. It can provide pain relief by providing postural correction and reducing loads on the fracture sites leading to alignment of the vertebral bodies. However, long-term use may lead to muscle weakness with atrophy and further physical deconditioning.11

Traditionally, conservative treatment consists of a combination of back bracing for 3 months excluding patients with neurological injury and unstable fracture, specific analgesia, and medication to treat osteoporosis. Immobilisation with a brace is not well tolerated by older patients. It also requires regular radiological monitoring to detect worsening of displacement and vertebral fracture malunion leading to chronic residual pain.

Although the efficacy of the regular use of back bracing in patients with vertebral osteoporotic fractures is not supported by scientific evidence, Norton and Brown4 described the efficiency of back braces, concluding that they exert pressure at three points on bony prominences to remind the patient to change or maintain posture. However, Morris et al.12 found that increased abdominal pressure decreases the net force applied to the spine when attempting to lift from the floor.

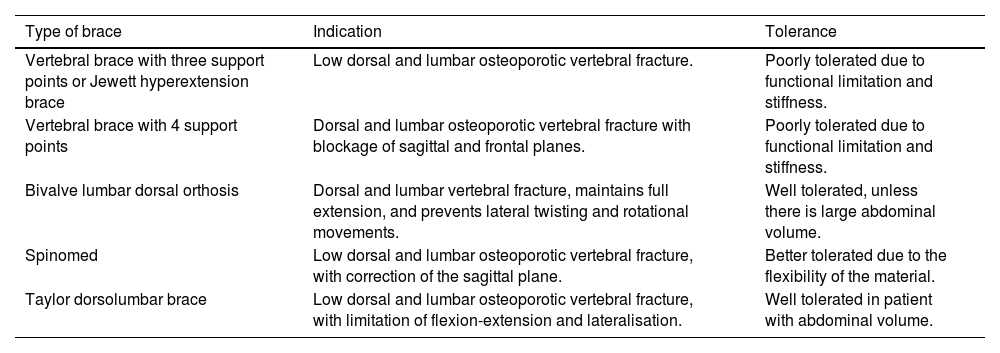

However, three-point braces (3PB) are the most commonly used means of fracture treatment, their support points being sternal, suprapubic, and dorsolumbar13 but their use in patients with osteoporotic fractures is limited by potential complications such as atrophy of the paraspinal musculature and respiratory restriction leading to low tolerance and in turn poor adherence to bracing. However, the Spinomed dynamic back brace has been an alternative since 1991, because by means of an adjustable aluminium structure that occupies almost the entire dorsolumbar hinge and, through a connection with lined and padded bands that hook through the shoulders in its upper part and an adjustable band in the lower abdominal region, it allows greater mobilisation for patients in activities of daily living and especially in paravertebral muscle activation14 (see Table 1).

Summary of recommended dorsal and lumbar braces.

| Type of brace | Indication | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Vertebral brace with three support points or Jewett hyperextension brace | Low dorsal and lumbar osteoporotic vertebral fracture. | Poorly tolerated due to functional limitation and stiffness. |

| Vertebral brace with 4 support points | Dorsal and lumbar osteoporotic vertebral fracture with blockage of sagittal and frontal planes. | Poorly tolerated due to functional limitation and stiffness. |

| Bivalve lumbar dorsal orthosis | Dorsal and lumbar vertebral fracture, maintains full extension, and prevents lateral twisting and rotational movements. | Well tolerated, unless there is large abdominal volume. |

| Spinomed | Low dorsal and lumbar osteoporotic vertebral fracture, with correction of the sagittal plane. | Better tolerated due to the flexibility of the material. |

| Taylor dorsolumbar brace | Low dorsal and lumbar osteoporotic vertebral fracture, with limitation of flexion-extension and lateralisation. | Well tolerated in patient with abdominal volume. |

A 2022 study by Weber A, et al. demonstrated that continuous wearing of a dynamic brace for 6 weeks resulted in a more upright posture, which appeared to have a positive effect on gait and stability.13 This protocol was for a multicentre randomised controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dynamic bracing versus standard care alone. The hypothesis was that, in patients with an osteoporotic vertebral fracture, dynamic bracing would improve quality of life with a positive effect on pain, sagittal spinal alignment, physical activity, and decrease the recurrence rate of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Due to the study design, the results were interpreted with caution and higher-level evidence is needed to analyse whether these effects are due to dynamic bracing or to natural recovery after an osteoporotic vertebral fracture. They conclude that dynamic bracing is a cost-effective treatment for patients with an osteoporotic vertebral fracture.13

In 2019, Christina Kaijser Alin concluded that there was no significant difference in back pain, back extensor strength, or kyphosis index after 6 months of treatment. In the back brace group, pain decreased slightly, and strength increased by 26.9%, which indicates that back bracing could become an alternative treatment method.15

In 2004, Pfeifer et al.16 published a prospective, randomised, crossover study, using an intention-to-treat analysis with two groups of 31 people in each. Group A used the back brace for 6 months and Group B was the control group. The following was observed in the back brace group:

- -

Increase in back extensor strength (73%) and increase in abdominal flexor strength (58%).

- -

An 11% decrease in angle of kyphosis.

- -

A 7% increase in vital capacity.

- -

A 38% decrease in average pain resulting in a 15% increase in well-being.

- -

27% reported a decrease in limitations of daily living.

Overall tolerability of the brace was good, no side effects were reported, and the drop-out rate was 3%, which is considered rather low.

In 2011, Pfeiffer et al. concluded that back bracing increases trunk muscle strength and therefore improves posture in patients with vertebral fractures caused by osteoporosis. In addition, better quality-of-life is achieved by pain reduction, decreased limitations of daily living, and improved well-being. Therefore, back bracing may be an efficacious nonpharmacological treatment option for spinal osteoporosis.17

A 2022 systematic review18 highlights that wearing a back brace for at least 2h per day for six months significantly reduced the thoracic kyphosis angle and improved back pain, extensor strength, and quality of life in older women with osteoporosis.

Squires et al.19 report that current knowledge on conservative management for thoracolumbar compression fractures is inadequate. All comparisons for function, quality of life, radiographic kyphotic progression, and opioid use showed statistically insignificant differences between bracing modalities.19

Education of patients with osteoporotic vertebral fractures is essential to avoid bed rest that results in muscle atrophy, impaired activities of daily living, worsening pain, limitation of vital respiratory capacity, and worsening of kyphotic deformity. Back bracing is still under discussion and more publications are needed. However, although there is nothing to contradict it, its benefit has been observed in some patients, relieving pain when walking and avoiding uncomfortable posture that worsens the fracture, it is also necessary to watch out for excessive compression, skin lesions, and other issues.

In summary, the decision to use back bracing must balance the potential benefits against the possible risks, such as long-term muscle weakness. Continued research is essential to fully understand the efficacy and safety of back bracing in the management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

FundingNo funding was received for this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.