To analyse the differences in the management of ankle fractures between orthopaedic/trauma surgeons and foot and ankle specialists.

Material and methodAn e-mail survey was performed asking some of the country's orthopaedic surgeons controversial questions regarding the analysis of 5 clinical cases of different ankle fractures.

ResultsSeventy-two surgeons responded to the questionnaire (response rate of 24.2%): 37 foot and ankle specialists and 35 non-specialist orthopaedic surgeons. For trimalleolar fracture, 40.5% of the specialists would request a computed tomography scan compared to 14% of the non-specialists (p=.01). Ninety-four percent of all the respondents would synthesise the posterior malleolus; 91% of the non-specialists would use an antero-posterior approach, either with a plate or with screws (p=.006). No differences were found between groups in the treatment of syndesmotic injuries (p>.05). For trans-syndesmotic fracture (Weber B) with signs of medial instability, 54% of the non-specialists would revise the internal lateral ligament compared to only 32% of the specialists (p=.06).

ConclusionsThe foot and ankle specialists ask for more complementary tests to diagnose ankle fractures. In turn, they use a greater diversity of surgical techniques in synthesis of the posterior malleolus (posterior plate) and the medial malleolus (cerclage wires). Finally, they indicated a lower revision rate of the internal lateral ligament.

Analizar las diferencias en el manejo de las fracturas de tobillo entre cirujanos ortopédicos/traumatólogos y especialistas en enfermedad de pie y tobillo.

Material y métodoSe realizó una encuesta vía correo electrónico que planteaba cuestiones controvertidas a propósito del análisis de 5 casos clínicos de diferentes fracturas de tobillo a cirujanos ortopédicos del país.

ResultadosSetenta y dos cirujanos respondieron la encuesta (tasa de respuesta del 24,2%): 37 especialistas en pie y tobillo y 35 cirujanos ortopédicos no especialistas. En el caso de la fractura trimaleolar, el 40,5% de los especialistas solicitarían una tomografía computarizada frente al 14% de los no especialistas (p=0,01). El 94% de todos los que respondieron sintetizaría el maléolo posterior; el 91% de los no especialistas, con tornillos vía anteroposterior, mientras que el 43% de los especialistas utilizarían la vía posteroanterior, bien con placa o con tornillos (p=0,006). No se hallaron diferencias entre grupos en el tratamiento de las lesiones sindesmales (p>0,05). En las fracturas transindesmales (B de Weber) con signos de inestabilidad medial, el 54% de los no especialistas revisarían el ligamento lateral interno frente a solo el 32% de los especialistas (p=0,06).

ConclusionesLos especialistas en pie y tobillo solicitan más pruebas complementarias para el diagnóstico de las fracturas de tobillo. A su vez, utilizan una mayor diversidad de técnicas quirúrgicas en la síntesis de los maléolos posterior (vía posterior-placas) y medial (cerclajes). Por último, indican una menor tasa de revisión del ligamento lateral interno.

Ankle fractures are highly prevalent injuries, considered to be the most frequent intraarticular fractures in a load-bearing joint and comprising 9% of all skeletal fractures.1 They also present an extensive variability with regards to the type of injury and its treatment.2 Despite the extreme specialisation of orthopaedic surgery, the frequency of this type of fracture in daily practice leads to several types of professionals participating in its management, from general orthopaedic surgeons to foot and ankle specialists, or trauma specialists. As a result of this and also the diversity of factors which have an impact on the decision-making of each type of lesion, several aspects are currently under discussion. These include diagnoses, surgical options and postoperative protocols to be followed.

Existing literature is not able to establish clinical practice guidelines based on scientific evidence with respect to fractures affecting the posterior tibial malleolus or tibioperoneal syndesmosis.3,4 Neither are there any established postoperative management aspects regarding ideal non-weight bearing time for this type of injury.5

The aim of this study was to analyse the differences in ankle fracture management among orthopaedic/trauma surgeons and foot and ankle specialists.

Material and methodA survey was designed for this study through an online platform: www.surveymonkey.com. The first part of the questionnaire consisted of 2 basic demographic questions: (1) if the respondent belonged to a unit specialising in foot and ankle disorders, and (2) how many years of experience the professional respondent had.

In the second part the respondent was asked about which classification or classifications of ankle fractures they were using in their daily practice.

The third part of the survey consisted of 24 items: 18 questions on 5 cases of ankle fractures selected to represent the different patterns of injury likely to be controversial with regards to management, and 6 general questions on the approach used for tibioperoneal syndesmosis injuries.

The cases included plain radiographs of fractures and were presented in the context of a young, active patient with no clinical history of interest.

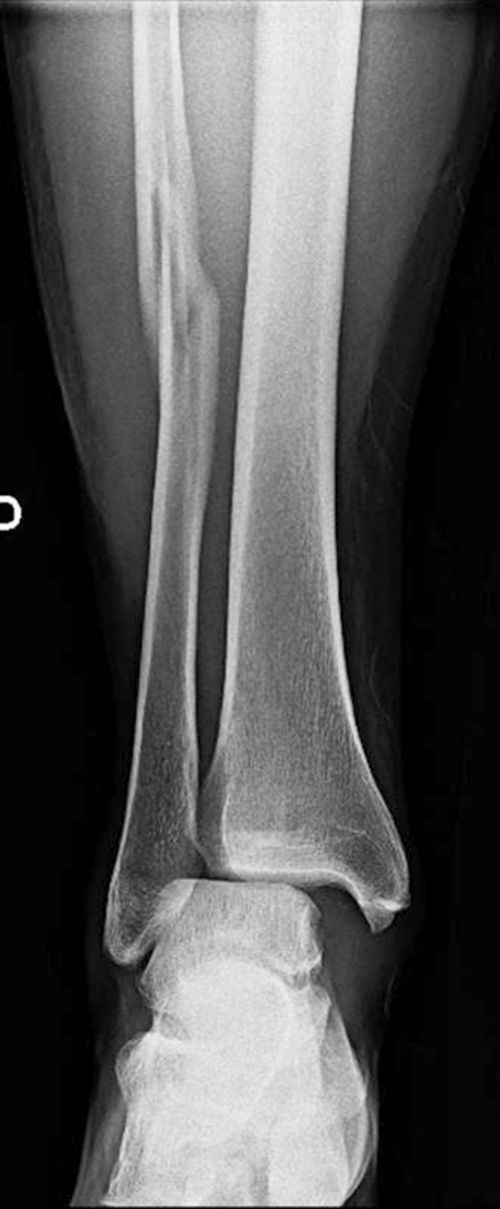

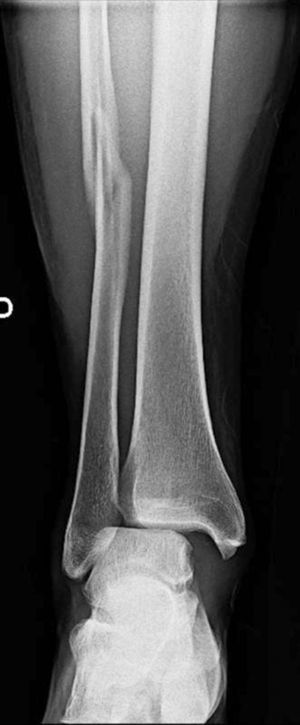

Case 1 consisted of a trimalleolar fracture with a posterior malleolar fragment involving approximately 40% of the joint surface (Fig. 1). Case 2 presented a Dupuytren type fracture above the syndesmosis (Fig. 2) and case 3 a spiral-type fracture of the peroneal above the syndesmosis with a lesion associated with tibioperoneal syndesmosis, the interosserous membrane and the deltoid ligament, or Maisonneuve type (Fig. 3.). Case 4 presented with a fracture transverse to the syndesmosis of non displaced fibula (Fig. 4). Lastly, case 5 presented with a fracture transverse to the syndesmosis of the displaced fibula with an increase in the medial tibiotalar space (Fig. 5).

An email was sent with the survey link to 300 orthopaedic surgeons in 7 hospital centres in the country and all the members of the Foot and Ankle Surgery Group of Barcelona. Between January and June 2015, 75 physicians responded to the survey, comprising a 25% (75/300) response rate. However, out of the total, 3 professionals sent an incomplete response, and the final effective response rate was therefore 24.2% (72/297).

Statistical analysis was made using the Chi-square test for paired data and the exact Fisher test for dichotomous variables from the SPSS software package, with a statistical significance level of p<.05.

Results37 food and ankle specialists (51.4%) responded and 35 orthopaedic non specialist surgeons (48.6%) responded. The professional experience of the sample was a mean of 13 years (range from 1 to 20 years).

The most used ankle fracture classification by the respondents was that of Weber – 71% of the professionals interviewed stated they used it, followed by the classification Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) (53%) and the Lauge-Hansen (49%) classification. Moreover, 73% of the specialists and 71% of the non specialists used more than one classification of the proposals in the survey. There used more than one classification of those proposed in the survey. There were no significant differences in the classifications used between the specialists and the non specialists in foot and ankle (Figs. 1–5).

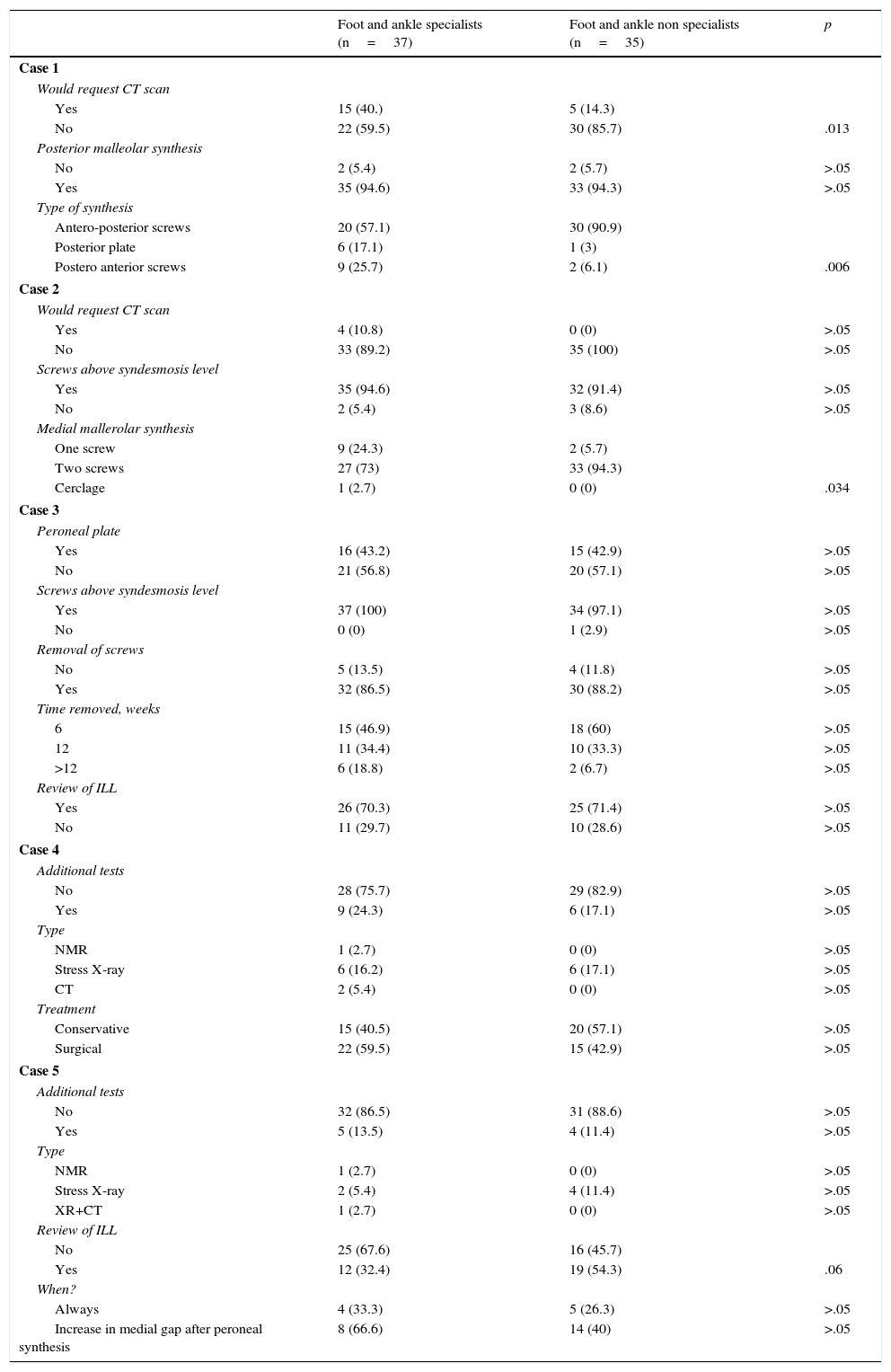

The results of the different questions are shown in Tables 1 and 2, specifically separated by specialists and non specialists in foot and ankle diseases.

Questions on clinical cases (1–5).

| Foot and ankle specialists (n=37) | Foot and ankle non specialists (n=35) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | |||

| Would request CT scan | |||

| Yes | 15 (40.) | 5 (14.3) | |

| No | 22 (59.5) | 30 (85.7) | .013 |

| Posterior malleolar synthesis | |||

| No | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) | >.05 |

| Yes | 35 (94.6) | 33 (94.3) | >.05 |

| Type of synthesis | |||

| Antero-posterior screws | 20 (57.1) | 30 (90.9) | |

| Posterior plate | 6 (17.1) | 1 (3) | |

| Postero anterior screws | 9 (25.7) | 2 (6.1) | .006 |

| Case 2 | |||

| Would request CT scan | |||

| Yes | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | >.05 |

| No | 33 (89.2) | 35 (100) | >.05 |

| Screws above syndesmosis level | |||

| Yes | 35 (94.6) | 32 (91.4) | >.05 |

| No | 2 (5.4) | 3 (8.6) | >.05 |

| Medial mallerolar synthesis | |||

| One screw | 9 (24.3) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Two screws | 27 (73) | 33 (94.3) | |

| Cerclage | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | .034 |

| Case 3 | |||

| Peroneal plate | |||

| Yes | 16 (43.2) | 15 (42.9) | >.05 |

| No | 21 (56.8) | 20 (57.1) | >.05 |

| Screws above syndesmosis level | |||

| Yes | 37 (100) | 34 (97.1) | >.05 |

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | >.05 |

| Removal of screws | |||

| No | 5 (13.5) | 4 (11.8) | >.05 |

| Yes | 32 (86.5) | 30 (88.2) | >.05 |

| Time removed, weeks | |||

| 6 | 15 (46.9) | 18 (60) | >.05 |

| 12 | 11 (34.4) | 10 (33.3) | >.05 |

| >12 | 6 (18.8) | 2 (6.7) | >.05 |

| Review of ILL | |||

| Yes | 26 (70.3) | 25 (71.4) | >.05 |

| No | 11 (29.7) | 10 (28.6) | >.05 |

| Case 4 | |||

| Additional tests | |||

| No | 28 (75.7) | 29 (82.9) | >.05 |

| Yes | 9 (24.3) | 6 (17.1) | >.05 |

| Type | |||

| NMR | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | >.05 |

| Stress X-ray | 6 (16.2) | 6 (17.1) | >.05 |

| CT | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0) | >.05 |

| Treatment | |||

| Conservative | 15 (40.5) | 20 (57.1) | >.05 |

| Surgical | 22 (59.5) | 15 (42.9) | >.05 |

| Case 5 | |||

| Additional tests | |||

| No | 32 (86.5) | 31 (88.6) | >.05 |

| Yes | 5 (13.5) | 4 (11.4) | >.05 |

| Type | |||

| NMR | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | >.05 |

| Stress X-ray | 2 (5.4) | 4 (11.4) | >.05 |

| XR+CT | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | >.05 |

| Review of ILL | |||

| No | 25 (67.6) | 16 (45.7) | |

| Yes | 12 (32.4) | 19 (54.3) | .06 |

| When? | |||

| Always | 4 (33.3) | 5 (26.3) | >.05 |

| Increase in medial gap after peroneal synthesis | 8 (66.6) | 14 (40) | >.05 |

ILL: internal lateral ligament; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; XR: X-ray; CT: computed tomography.

The data are shown as the number of responses, with the percentage value in brackets. An analysis was performed using the Chi-square test.

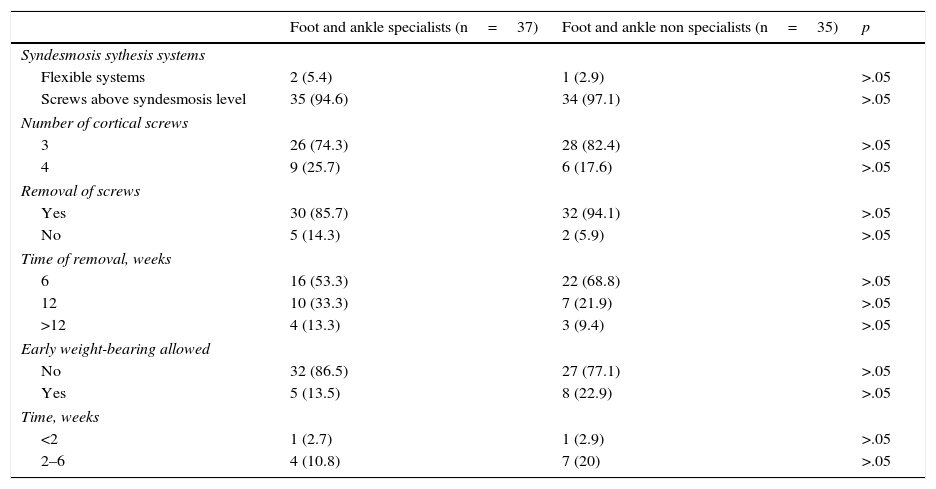

Management of tibioperoneal syndesmosis injuries.

| Foot and ankle specialists (n=37) | Foot and ankle non specialists (n=35) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syndesmosis sythesis systems | |||

| Flexible systems | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.9) | >.05 |

| Screws above syndesmosis level | 35 (94.6) | 34 (97.1) | >.05 |

| Number of cortical screws | |||

| 3 | 26 (74.3) | 28 (82.4) | >.05 |

| 4 | 9 (25.7) | 6 (17.6) | >.05 |

| Removal of screws | |||

| Yes | 30 (85.7) | 32 (94.1) | >.05 |

| No | 5 (14.3) | 2 (5.9) | >.05 |

| Time of removal, weeks | |||

| 6 | 16 (53.3) | 22 (68.8) | >.05 |

| 12 | 10 (33.3) | 7 (21.9) | >.05 |

| >12 | 4 (13.3) | 3 (9.4) | >.05 |

| Early weight-bearing allowed | |||

| No | 32 (86.5) | 27 (77.1) | >.05 |

| Yes | 5 (13.5) | 8 (22.9) | >.05 |

| Time, weeks | |||

| <2 | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | >.05 |

| 2–6 | 4 (10.8) | 7 (20) | >.05 |

The data are shown as the number of responses, with the percentage value in brackets. Analysis was performed using the Chi-square test.

In the case of the trimalleolar fracture (case 1), 40.5% of specialists would request a computed tomography (CT) scan compared with 14% of non specialists, with this difference being significant (p=.01). 94% of the respondents would synthesise the posterior malleolus, with no differences between groups, except that the specialists would use a greater variety of techniques for this synthesis. 91% of the non specialists opted to use antero-posterior screw technique approach, whilst 43% of the specialists would use the postero-anterior technique, with either a plate or with screws (p=.006).

With regard to case 2, the Dupuytren type fracture above the syndesmosis, 93% of the surgeons would use screws above the syndesmosis, without any apparent differences between the two groups of surgeons. However, there were differences with respect to the type of synthesis used in the medial tibial malleolus. Whilst non specialists mostly used 2 cancellous bone screws (94%), 73% of the specialists used them, whilst using other options such as a single screw or a cerclage on the other occasions (p=.03). In this type of fracture, only 11% of specialists would request a TC.

In the Maisonneuve (case 3) fracture type we found there were no differences between groups on the issues raised. 43% of respondents would perform bone synthesis with a plate in the fibula (p=.97), 71% would review the internal lateral ligament (p=.91) and 99% would implant screws above the syndesmosis (p=.48). The removal of these screws would be made by 87% of the respondents, the majority after 6 weeks, with no differences between groups (p=.4).

In case 4, the fracture transverse to the syndesmosis of non displaced fibula, 24% of the specialists would request complementary tests compared with 17% of the non specialists (p=.45). Of the options put forward (TC, RMN and stress X-ray), 80% would prefer a stress X-ray. With regard to appropriate treatment for this type of fracture, 60% of the specialists consider surgical treatment compared with 40.5% of non specialists, but there was no statistical significance (p=.16).

In the last clinical case, fracture transverse to the syndesmosis with displaced fibula and increased medial tibiotalar space (case 5), 13.5% of specialists would request additional tests compared with 11.4% of non specialists. Again, of the options put forward, the majority would prefer stress X-ray. When asked if they would initially review the internal lateral ligament, 54% of non specialists would review it compared with only 32% of the specialists (p=.06). This review would be mainly carried out only if an increase in the medial space after fibular synthesis took place (74% compared with 66%). Only 14% and 11%, respectively, would review it in all cases.

With regards to analysis of the questions on general aspects of syndesmotic injuries, the majority of surgeons would use screws for syndesmosis synthesis. Only 5.5% of specialists would use flexible systems, compared with 3% of non specialists (p=1). Regarding the number of cortical syntheses wit screws, 78% of respondents synthesis 3 corticals, with no differences between groups (p=.42). Neither are there any differences between specialists and non specialists in screw removal: 86% and 94$ respectively would do this (p=.43). The screws above the syndesmosis are removed by the majority of surgeons after 6 weeks (53% of specialists compared with 69% of non specialists). The others would remove them after12 weeks (31% compared with 47%, respectively; p=.53). Lastly, only 13.5% of specialists would accept early weight-bearing, whilst 23% of non specialists would accept support before 6 weeks had passed (p=.66).

DiscussionThis survey shows the diagnostic and therapeutic preferences in management of ankle fractures in our environment, providing evidence that foot and ankle specialists request a higher number of diagnostic tests and dispose of a wider range of surgical techniques compared with orthopaedic surgeons.

In the references, similar surveys where specialists and non specialists in foot and ankle participate, only a specific type of injury or treatment aspect is dealt with, such as syndesmotic injuries or weight-bearing period. Furthermore, the majority of them do not analyse the differences between different types of specialists.5,6

The treatment of posterior malleolar fractures is in itself the purpose of a survey conducted by Gardner et al. for members of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society.7 This is an online questionnaire based on 5 clinical cases with a response rate of 20%, similar to our study. In contrast, the sample of 401 respondents presents greater heterogeneity: 50% of the participants are foot and ankle specialists, 24% in trauma, 2% in both sub-specialties and 24% in neither of them. Unlike this study, they show a higher preference of specialists in trauma due to the open reduction using the posterolateral approach and attachment with a posterior plate than the members of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society in the fractures which affect the posterior malleolus.

Swart et al. conducted a survey for 702 members of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (34%) and of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (67%) through an online platform over the weight-bearing period to be followed after the synthesis of 3 types of ankle fracture in different types of patients. Its 31% response rate presents a wide range of outcomes, mainly influenced by the type of injury and comorbidity of the patient, but it does not analyse the results by specialist type.5

In the Low Countries, Schepers et al. used a postal survey which was sent to 86 hospitals, with a response from 207 specialists in trauma and 281 orthopaedic surgeons with respect to the treatment of syndesmosis injuries, and a response rate of 74%. Their results are comparable with those established by the previous reference, except for the higher rate of material removal. The only difference between both groups is higher use of 4.5mm screws for the stabilisation of syndesmosis by orthopaedic surgeons compared with trauma specialists.8 In this study we did not find any differences between the professionals of both sub-specialties with regards to technical aspects of syndesmosis stabilisation (number of corticals, removal of screws or weight-bearing time).

With regards to the review of the deltoid ligament in the type B Weber fractures with an increased medial tibiotalar space, the studies which reviewed scientific evidence in this respect suggest that direct repair of the same is not essential after correct peroneal synthesis.9–11 We found no references to determine the therapeutic approach in these controversial cases whilst bearing in mind the surgeon's speciality. In this study it is precisely the foot and ankle surgeons who would indicate review of the deltoid ligament to a lower degree. This could be due to greater updating of these subspecialists in ankle fractures.

Regarding preoperative additional tests, Gibson et al. recently observed that more than 25% of surgeons make changes to their therapeutic strategy after analysing CT imaging, and they therefore recommend its use in the management of all trimalleolar fractures.12 This would be consistent with the fact that almost half of foot and ankle surgeons in this study would request a CT scan in this type of injury.

The response to surveys is usually a low priority activity for health professionals fully engaged in healthcare duties.13 Specifically, surgeons are usually characterised by their low response rates, ranging between 20% and 30%.6,14 Despite the fact that a low response rate means lower external validity (ideally, over 70%),15 this type of study makes it possible to establish attitudes and trends regarding the management of different aspects in clinical practice.

Although generally systematic review of prospective, randomised studies is accepted as a source of higher evidence for therapeutic guidelines, the scarcity of this type of study in surgery means that in daily clinical practice our decisions are not based on a high level of evidence.16 Despite this, Eddy established that the consensual therapeutic strategies in over 95% of them could be described as standard when the level of evidence was not high.17 Of the diverse aspects presented in this study, only the indication for screws above the syndesmosis in Maisonneuve type fractures and the use of screws as a method for tibiotalar syndesmosis attachment gained such consensus (in both subgroups of surgeons) and could thus be considered as standard clinical practice in the management of ankle fractures among the population surveyed.

If the respondents of a survey belong to a specific region, this may lead to bias and results which may not be extrapolated. However, a national survey like this one provides greater validity for broadening results, but associated with a lower response rate.8,12,18 The lower response rate obtained (24.2%) would thus be the main limitation of our study.

ConclusionsThe results of this survey, which involves different types of ankle fracture shows that the foot and ankle specialists request more complementary tests in the diagnosis. In turn, they use greater diversity of surgical techniques in the posterior and medial malleolar synthesis. Lastly, they indicate a lower rate of internal lateral ligament review after correct peroneal synthesis in Weber type B fractures.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been performed on humans or animals in this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: González-Lucena G, Pérez-Prieto D, López-Alcover A, Ginés-Cespedosa A. Controversias en fracturas de tobillo: ¿es diferente la visión del especialista en pie y tobillo? Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:27–34.