Charcot arthropathy of the spine is a neuropathic affectation of the spine, it is considered rare, has a destructive and progressive evolution. It is usually due to a previous traumatic injury, but it has also been described as secondary to other infectious or tumoural processes. Initially, surgical treatment has always been considered for possible complications such as pain control and trunk instability. We present a series of 13 cases diagnosed with Charcot arthropathy at the Institut Guttmann, in which the following variables are described: aetiology (traumatic, infectious, iatrogenic), clinical features (pain, loss of trunk control, vegetatism, spasticity), interval of onset of the clinical features, location (L2-L3), treatment (surgical or conservative) and the evolution they presented, with the aim of evaluating conservative treatment as the first option, instead of surgery. In our sample, 61.5% (8/13) were treated surgically with posterior instrumentation (7/8), except for one case which was anterior and posterior; 38.5% (5/13) were treated conservatively and none required subsequent surgery. In conclusion, our line of action would initially be to consider conservative treatment, and to use surgery for cases in which the clinical evolution was not as expected, either due to poor pain control and/or limitation of mobility secondary to the deformity limitation of mobility secondary to the deformity of the trunk, or when the spinal involvement or the patient's symptoms are not tolerated and require a quicker and more aggressive solution.

La artropatía de Charcot en el raquis es una afectación neuropática de la columna, es considerada como rara, tiene una evolución destructiva y progresiva. Habitualmente suele ser debida a una lesión traumática previa, pero también se ha descrito secundaria a otros procesos infecciosos, tumorales. Inicialmente siempre se ha planteado un tratamiento quirúgico para las posibles complicaciones como son el control del dolor y la inestabilidad del tronco. Se presenta una serie de 13 casos diagnosticados de artropatía de Charcot en el Institut Guttmann, donde se describen como variables: la etiología (traumática, infecciosa, iatrogénica), la clínica (dolor, pérdida de control de tronco, vegetatismo, espasticidad), el intervalo de aparición de la clínica, la localización (L2-L3), el tratamiento (quirúrgico o conservador) y la evolución que presentaron, y se pretende valorar el tratamiento conservador como primera opción, en lugar de la opción quirúrgica. En nuestra muestra, el 61.5% (8/13) fueron tratados quirúrgicamente con instrumentación posterior (7/8), salvo un caso que fue anterior y posterior; el 38.5% (5/13) fueron tratados de manera conservadora y ninguno necesito una cirugía posterior. En conclusión, nuestra línea de actuación sería inicialmente contemplar un tratamiento conservador, y utilizar la cirugía para casos en los que la evolución de la clínica no fuera la esperada, bien por un mal control del dolor y/o la limitación de la movilidad secundaria a la deformidad del tronco, o cuando la afectación raquídea o la clínica que presenta el paciente no fuera tolerada y necesitara de una solución más rápida y agresiva.

Charcot arthropathy of the spine, also known as spinal neuroarthropathy, is an unusual disease that evolves progressively and destructively. It affects the vertebral body, the intervertebral disc, and the posterior ligamentous complex.

It is due to the loss of deep sensation, due to the destruction of afferent sensory fibres that allow small traumas to go unnoticed, causing mechanical degeneration of the facet joint.1

It may be associated aetiopathologically with diseases such as diabetic neuropathy, tertiary syphilis, syringomyelia, congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis (CIPA), infectious disease, tumours, post-radiation therapy and most commonly with spinal cord injury.2

Initially studied in 1868 by Jean-Martin Charcot who reported a causal relationship between neurological damage and bone and joint injury. In this case it was related to patients with tertiary syphilis and destruction of peripheral joints.3

It was as early as 1884 when Kronig first described the onset of spinal injury in a diabetic patient; but it was not until 1978 that Slabaugh et al. described the first case secondary to spinal cord injury.3–5

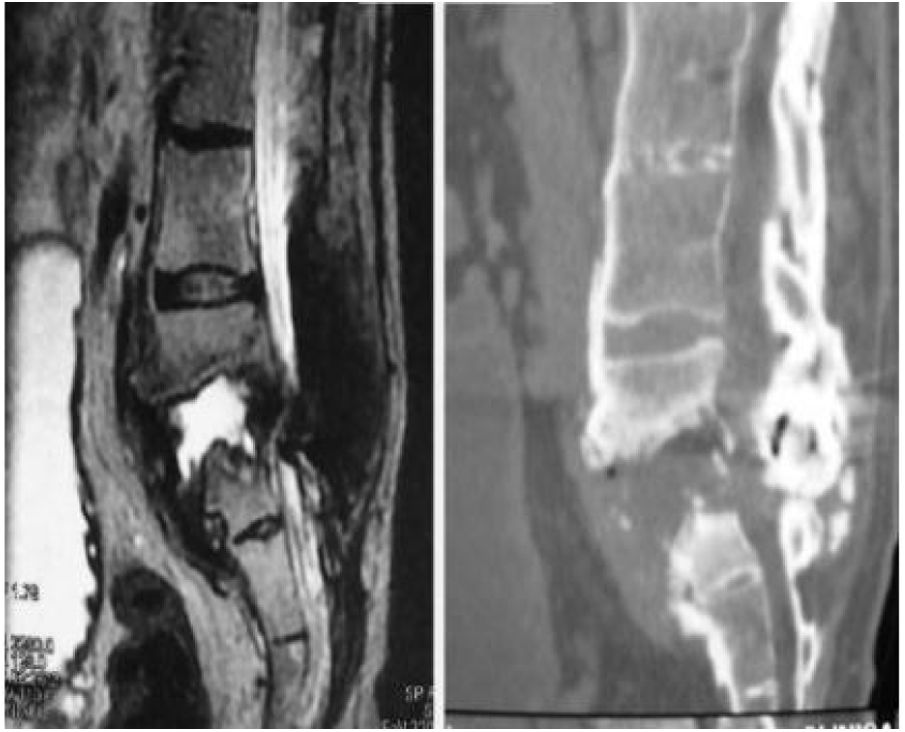

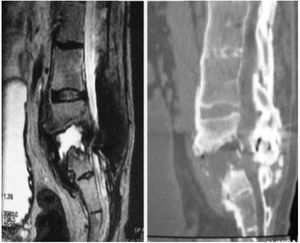

We now see that the main cause of Charcot arthropathy is traumatic injury to the spinal cord. The area most affected is the thoracolumbar junction.3–5 Vertebral and disc degeneration, osteopenia and vertebral collapse occur, especially with destructive lesions in the posterior vertebral joints in association with fibrosis formation of the perivertebral tissue that can take place during the degenerative process. This injury to the three spinal columns can eventually cause vertebral instability, subluxation or even vertebral dislocation leading to kyphosis, scoliosis, or both. Kyphosis type deformity is the most prevalent and disabling. It is also often associated with back pain, neurological changes such as spasticity, loss of sensation, loss of trunk control, loss of sphincter control, dysreflexia, and autonomic symptoms such as hyperhidrosis, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, as well as an audible cracking noise when changing position (Fig. 1).3–5

Charcot arthropathy of the spine is probably underdiagnosed, and is often diagnosed late, due to its non-specific clinical presentation and because a differential diagnosis needs to be made with diseases such as chronic infections (spondylodiscitis) or tumours. However, it is very important to know how to recognise this disease due to its disabling consequences in patients with spinal cord injury.3–5

Material and methodsA retrospective observational study of a series of 13 cases diagnosed with Charcot arthropathy of the spine from 2004 to 2016 at the Institut Guttmann in Badalona (Barcelona).

Adult patients of all genders with a diagnosis of Charcot and a follow-up of at least two years (range: two to 11 years) were included).

We collected sociodemographic data (age and sex), diagnoses (origin of the neuropathic lesion [traumatic, medical such as myelitis or abscesses, and iatrogenic due to the placement of a sacral anterior root electro-stimulator system for sphincter control [SARS], interval between diagnosis of Charcot and initial surgery), location of the Charcot arthropathy and neuromuscular status, location of the Charcot arthropathy and neurological status assessed using the ASIA scale]), clinical variables (pain, trunk instability, autonomic signs and symptoms and spasticity) and treatment-related variables (type of treatment [surgical or conservative] and type of surgical instrumentation [anterior or anterior/posterior]).

Charcot spine was diagnosed based on radiological changes on plain radiography, CT and MRI scans that included intervertebral disc destruction, osteophytes, facet joint erosions or growths, spondylolisthesis, hyperkyphosis, in addition to pseudarthrosis. Results compatible with destructive spondylodiscitis. To complete the differential diagnosis with infectious, inflammatory and tumour pathology, a negative gallium scan and lumbar puncture culture were also required, as well as negative analytical parameters of infectious activity, CRP, ESR and HLA B27.6,7

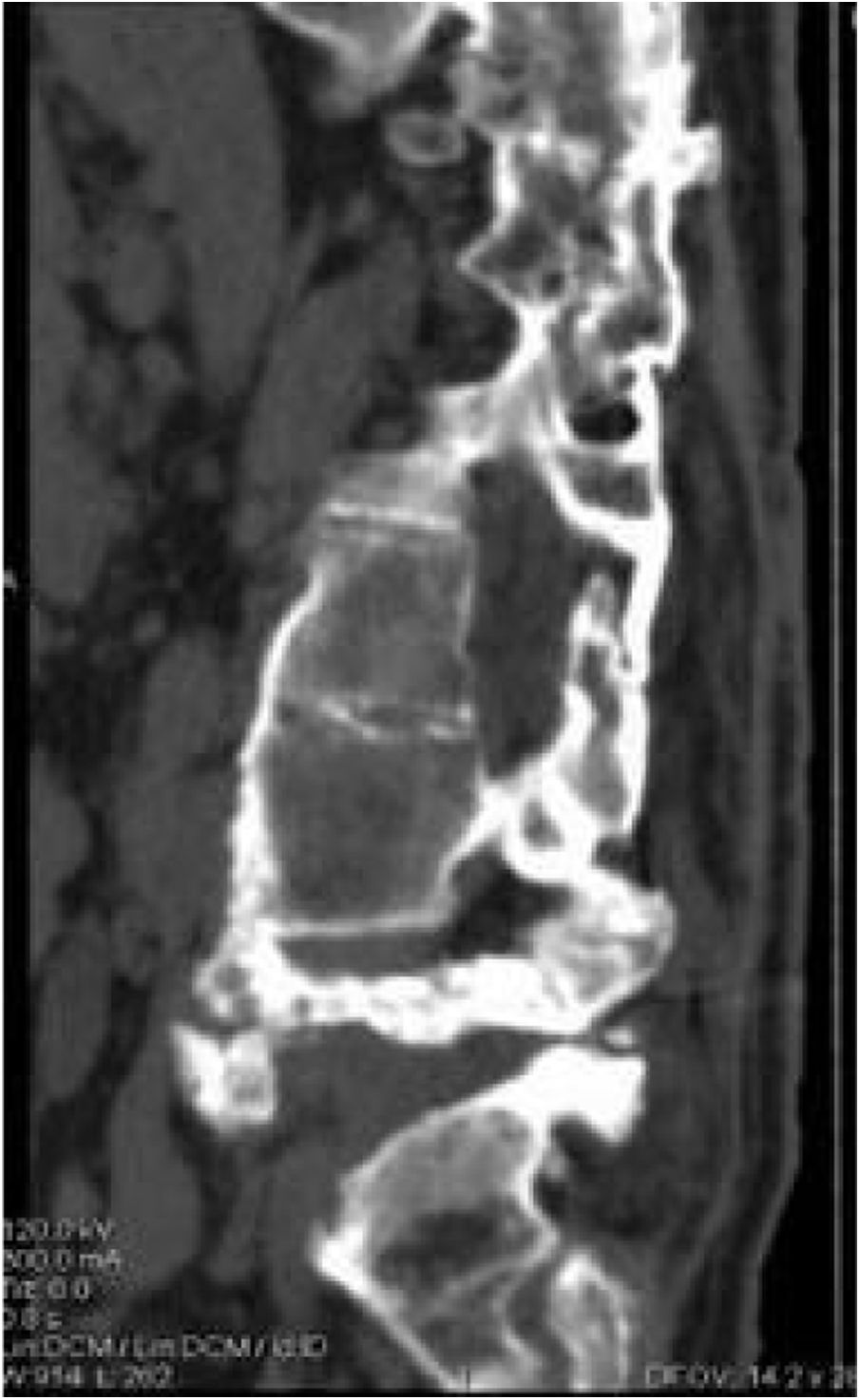

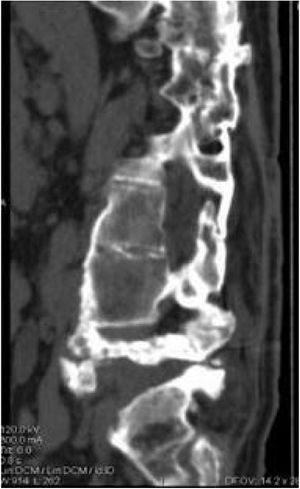

The patients received either surgical or conservative treatment according to their clinical situation. Surgical treatment was initially considered in patients with significant trunk instability, poorly controlled pain, and advanced neurological symptoms. In seven patients, treatment consisted of posterior stabilisation and reduction of the deformity by posterolateral arthrodesis with pedicle screws of three proximal and two or three distal segments, with posterior closure osteotomy to achieve fusion of the affected somas, and use of a lateral traction device or cross-link, to avoid the complication of hinge effect. An anterior approach with intersomatic graft placement was used in one case, which increases the stability of the construction but also increases the morbidity of the surgery (Figs. 2 and 3), as opposed to conservative treatment based on follow-up, with no aggressive intervention, just the use of braces.

Statistical analysis: STATA statistical software was used for the data analysis.

Quantitative variables were expressed with their measure of central tendency and deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

ResultsOf the 13 patients included in our series, 23% (3/13) had scoliosis secondary to myelitis in two of the cases, one during the first year of life and the other at the age of six, the third patient had a vertebral abscess, compatible with spondylodiscitis due to Staphylococcus aureus. Seventy-seven per cent (10/13) had a previous fracture of the spine. Of the total number of patients, 69% (9/13) had undergone previous stabilisation surgery, including the patient with the vertebral abscess and eight of the patients with a previous fracture, the other two with a previous fracture did not undergo surgery at the time of the initial injury.

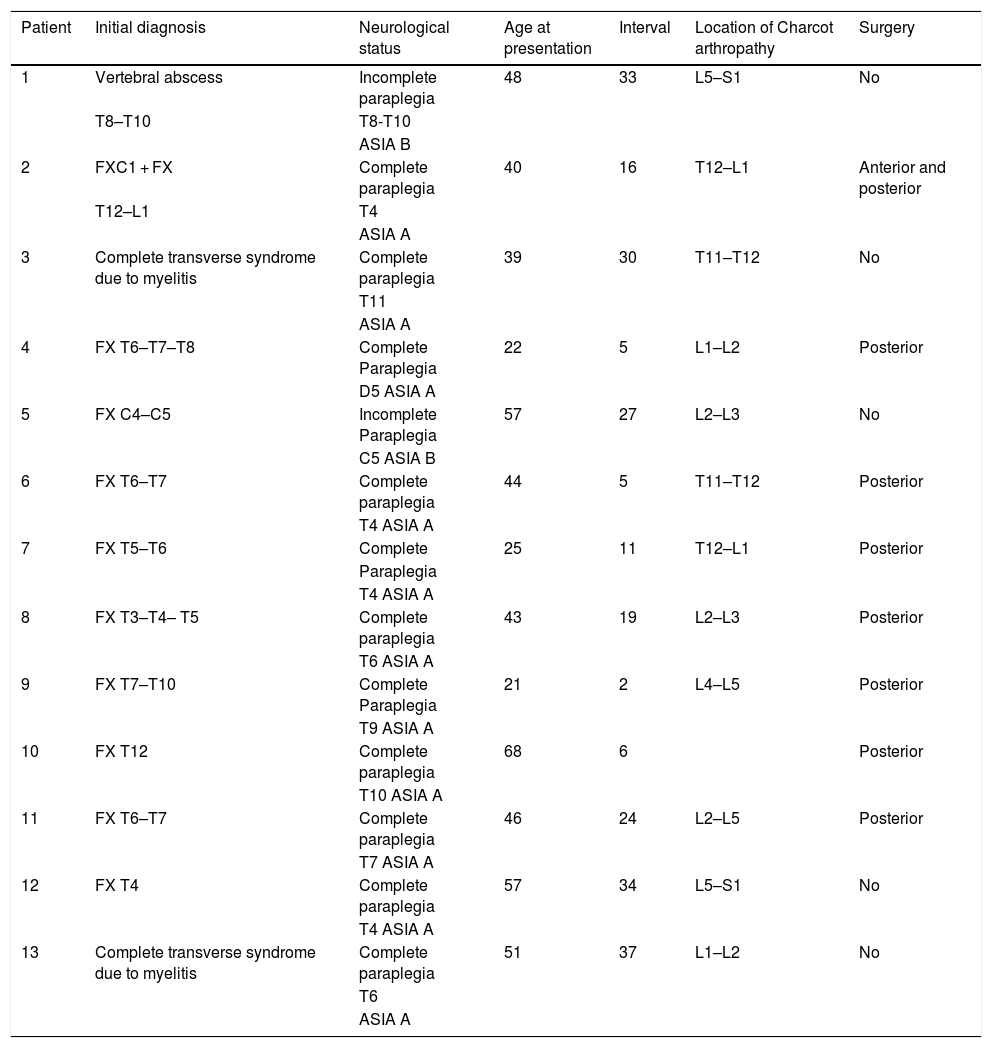

The origin of the injuries was grouped into three groups; 54% were traumatic disease, 31% paralytic scoliosis, and finally 15% were iatrogenic related to wide L1-L2 laminectomy for placement of SARS. (Tables 1 and 2).

Patient demographics.

| Patient | Initial diagnosis | Neurological status | Age at presentation | Interval | Location of Charcot arthropathy | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vertebral abscess | Incomplete paraplegia | 48 | 33 | L5–S1 | No |

| T8–T10 | T8-T10 | |||||

| ASIA B | ||||||

| 2 | FXC1 + FX | Complete paraplegia | 40 | 16 | T12–L1 | Anterior and posterior |

| T12–L1 | T4 | |||||

| ASIA A | ||||||

| 3 | Complete transverse syndrome due to myelitis | Complete paraplegia | 39 | 30 | T11–T12 | No |

| T11 | ||||||

| ASIA A | ||||||

| 4 | FX T6–T7–T8 | Complete Paraplegia | 22 | 5 | L1–L2 | Posterior |

| D5 ASIA A | ||||||

| 5 | FX C4–C5 | Incomplete Paraplegia | 57 | 27 | L2–L3 | No |

| C5 ASIA B | ||||||

| 6 | FX T6–T7 | Complete paraplegia | 44 | 5 | T11–T12 | Posterior |

| T4 ASIA A | ||||||

| 7 | FX T5–T6 | Complete | 25 | 11 | T12–L1 | Posterior |

| Paraplegia | ||||||

| T4 ASIA A | ||||||

| 8 | FX T3–T4– T5 | Complete paraplegia | 43 | 19 | L2–L3 | Posterior |

| T6 ASIA A | ||||||

| 9 | FX T7–T10 | Complete Paraplegia | 21 | 2 | L4–L5 | Posterior |

| T9 ASIA A | ||||||

| 10 | FX T12 | Complete paraplegia | 68 | 6 | Posterior | |

| T10 ASIA A | ||||||

| 11 | FX T6–T7 | Complete paraplegia | 46 | 24 | L2–L5 | Posterior |

| T7 ASIA A | ||||||

| 12 | FX T4 | Complete paraplegia | 57 | 34 | L5–S1 | No |

| T4 ASIA A | ||||||

| 13 | Complete transverse syndrome due to myelitis | Complete paraplegia | 51 | 37 | L1–L2 | No |

| T6 | ||||||

| ASIA A |

ASIA: American Spinal Injury Association.

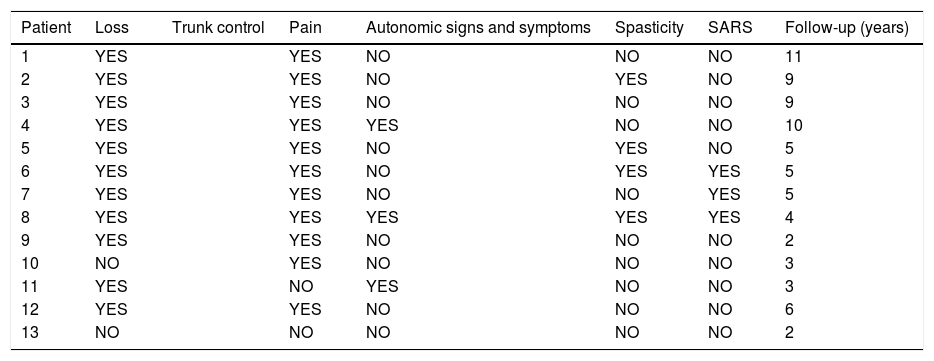

Patient symptoms and follow-up.

| Patient | Loss | Trunk control | Pain | Autonomic signs and symptoms | Spasticity | SARS | Follow-up (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | 11 | |

| 2 | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO | 9 | |

| 3 | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | 9 | |

| 4 | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | 10 | |

| 5 | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO | 5 | |

| 6 | YES | YES | NO | YES | YES | 5 | |

| 7 | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | 5 | |

| 8 | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | 4 | |

| 9 | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | 2 | |

| 10 | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | 3 | |

| 11 | YES | NO | YES | NO | NO | 3 | |

| 12 | YES | YES | NO | NO | NO | 6 | |

| 13 | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | 2 |

SARS: Sacral Anterior Root Stimulator.

The location of the Charcot arthropathy was distal to the initial lesion/instrumentation in 69% (9/13) of cases. In 23% (3/13) more specifically at level L2-L3; and 84.5% (11/13) the lesion was located one to three levels below the instrumentation.

The locations of the Charcot arthropathy varied widely in the series of patients, with 23% found at L2-L3 level; other frequent locations were the thoracolumbar hinge and levels adjacent to those already mentioned.

Regarding the clinical manifestations secondary to the Charcot arthropathy itself, it was found that 92% (12/13) of the cases presented some type of clinical manifestations compatible with increased spasticity 31% (4/13), dysreflexia and autonomic signs and symptoms (hyperhidrosis, hypotension, dizziness, nausea or vomiting) 23% (3/13), pain 85% (11/13) and discomfort, and loss of trunk control 85% (11/13) (Table 2).

Pain and limitation of mobility secondary to the deformity were raised as indications for treatment. A total of 38.5% (5/13) were treated conservatively with the use of braces and 61.5% (8/13) with surgical treatment, in the latter cases spinal stabilisation was performed with posterior instrumentation (7/8), except in one case where instrumentation was anterior and posterior. The goals of surgical treatment were primarily to correct kyphosis, improve pain and achieve solid spinal fixation (Table 1). None of the patients treated conservatively required subsequent surgical treatment.

Of the patients who underwent surgery, 50% (4/8) had complications secondary to surgery, including instrumentation failure 50% (2/4) and infection 25% (1/4), which we considered serious, and pressure ulcers 25% (1/4), considered moderate. The patients treated conservatively had complications of this type.

DiscussionCharcot arthropathy of the spine is a disease that progresses slowly. It is due to a combination of vertebral and intervertebral disc degeneration with massive bone formation secondary to spinal dislocation. The main mechanism of injury is damage to the innervation of the joint with loss of proprioception and pain/temperature sensitivity. This loss of sensitivity leads to a lack of defence mechanisms of the joint that would otherwise help prevent excessive ligament and disc stress and result in even distribution of loads. Normally, the stress on these ligaments causes a reflex contraction of the muscles and thus stabilises the joint. This failure leads to repeated microtrauma to the synovial joint cartilage resulting in subsequent destruction of the joint capsule itself. It causes hyperplastic and hypertrophic changes in the membrane and capsule with synovial effusion and progressive subluxation of the joint.1–8

It has also been suggested that loss of sympathetic innervation is a trophic factor that promotes hyperaemia and osteoclastic hyperactivity.

Some cases have been described in patients with chronic insensitivity to pain and temperature, an autosomal disease characterised by the absence of small unmyelinated fibres.3,9,10

In terms of spinal neuroarthropathy, mechanical factors will be critical. In paraplegic patients, the mechanical stress caused by chair positions and transfers themselves, which repeatedly expose the part of the mobile spine below the fused area to an area of stress, is very relevant, and the risk of Charcot arthropathy in the spine is higher in more active patients.1–5,8 The intervertebral zone is usually the most stressed and fragile area, typically in the thoracolumbar hinge and the lumbosacral transition zone.1–5,8

In patients who have undergone previous surgery, the typical location of Charcot arthropathy is the operated area itself or below the instrumentation area. According to our series, the location of the Charcot arthropathy was distal to the initial lesion, one to three levels below the instrumentation, and the L2-L3 level was the area most affected. Barrey et al., in their 2010 review, found that the most affected levels were L2–L3, L1–L2, T12–L1 and L4–L5, in that order.3

According to several authors, laminectomy appears to be, an aggravating factor for onset of the lesion.3,11–14 Loss of stability of the posterior elements, (the interspinous ligament, the spinous ligament, the lamina, the joint capsule), possible damage to the paravertebral musculature increase the stress, load on the rest of the articular elements such as, the intervertebral disc itself, the facet joints. Sobel et al. found development of Charcot arthropathy in four of their five laminectomies.11 In their series Vialle et al. treated six of their seven patients. In our series of,13 patients, three underwent laminectomy for placement of SARS.14

Clinical progression is usually very slow, and remains subclinical for months or years, until the advanced stages. Barrey et al. report a mean of 17.3 years; in their series it was 19 years. In our series the mean time of onset was also 19 years. Finally, the patient may present with non-specific and variable symptoms, but if there is an important level of suspicion, they can be referred satisfactorily. Common symptoms include local pain, loss of trunk control, progressive deformity (usually increased kyphosis), and autonomic signs and symptoms (hyperhidrosis, increased spasticity, dizziness, hypotension, nausea and/or vomiting). In paraplegic patients with complete neurological damage, the most frequent symptom is a feeling of instability in the sitting position and deformity. Pain and cracking sounds are also common. In patients with incomplete neurological injury, Charcot arthropathy often aggravates the previous neurological state, associated with increased spasticity, and in lesions above T6 or high paraplegics it may present as a dysautonomic syndrome combining hypertension, bradycardia, hyperhidrosis, and headache, also known as dysreflexia. This syndrome can be triggered by certain trunk movements or sitting position.3–8

Clinical progression is usually very slow, and remains subclinical for months or years, until the advanced stages. Barrey et al. report a mean of 17.3 years; in their series it was 19 years. In our series the mean time of onset was also 19 years. Finally, the patient may present with non-specific and variable symptoms, but if there is an important level of suspicion, they can be referred satisfactorily. Common symptoms include local pain, loss of trunk control, progressive deformity (usually increased kyphosis), and autonomic signs and symptoms (hyperhidrosis, increased spasticity, dizziness, hypotension, nausea and/or vomiting). In paraplegic patients with complete neurological damage, the most frequent symptom is a feeling of instability in the sitting position and deformity. Pain and cracking sounds are also common. In patients with incomplete neurological injury, Charcot arthropathy often aggravates the previous neurological state, associated with increased spasticity, and in lesions above T6 or high paraplegics it may present as a dysautonomic syndrome combining hypertension, bradycardia, hyperhidrosis, and headache, also known as dysreflexia. This syndrome can be triggered by certain trunk movements or sitting position.3–8

Disease progression can have two paths. One is towards healing, although the lesion itself does not disappear, but ankylosis of the posterior arches can occur, providing some stability that is sufficient and long-lasting. In cases like this the patient's clinical condition improves. Another possibility is progression towards mechanical instability and persistence of symptoms and the risk of worsening of the patient's previous neurological condition.

Clinical management, immobilisation with braces, and surgery are the available therapeutic options.

Charcot arthropathy has a destructive and progressive pattern, therefore we could initially consider surgical treatment as the first option in these patients.1–8 The main aim of surgery is to stabilise the affected spinal segment, correct sagittal balance, and eliminate pain.1–15 A quality fusion must be achieved by debridement of the inflamed and/or necrotic tissues to stabilise the segment. The anterior approach is the best according to some authors. All authors insist on anterior or posterolateral fixation of the anterior spine (50% of cases according to the surgical series of Vialle et al). The choice of the exact type of surgery will be based on the surgeon's training and personal preferences.

A single anterior approach is not sufficient in terms of stabilisation and carries the risk of complications. Arnold and Mohit et al. describe a posterolateral approach with decompression and intervertebral fixation with an instrumented posterior cage and fixation.15 However, many authors advocate a two-stage approach. Vialle et al. in their series of nine cases, performed a combined approach in eight, achieving bone fusion, improvement of pain, spasticity, and function.14 Suda et al. in 2007, in four cases, used an anterior and posterior approach with autologous bone grafting and subsequent stabilisation with osteosynthesis, and had satisfactory results in bone fusion and no complications.16

Aebli et al. in 2013, in a series of 28 patients, seven of whom were treated conservatively and 21 surgically, observed surgical treatment including extensive debridement, posterior instrumentation and circumferential spondylodesis as the current treatment option.7

To achieve kyphosis reduction, some authors suggest a small posterior osteotomy,17 and in cases where bone destruction is limited, a single posterior phase with intersomatic fusion may be sufficient. Morita et al. recommended this option in patients with a complete sensorimotor neurological injury. In their series of nine cases, bone fusion was achieved in all their patients at six months.8

The limits of the instrumentation site, particularly the lower limits, are a cause of debate according to the authors, since after bone fusion there is a risk of developing injury below the fixed segment. Brown et al. in 1992, in their series of eight patients, two had mechanical complications and two had new Charcot arthropathies below the area of instrumentation. Some authors systematically recommend extension up to the pelvis, but this has certain disadvantages, as it increases the complexity of the surgery and limits the patient's mobility.18 For example, Morita et al. found in one of the cases in their series that the patient was unable to perform self-catheterisation after surgery. In this respect, it is also important to assess the condition of the hips, as ankylosis of the hips leads to excessive tension in the lumbar region and can result in mechanical problems postoperatively.8 Haus et al., in their series of nine cases, suggested that sacral or pelvic fixation should be performed to prevent secondary development of a new Charcot joint, even if this would mean significant loss of mobility for the patient.6

De Iure et al. in 2015 stated that to achieve sagittal axis balance correction, extension to the sacrum or pelvis should be considered in some cases, even though it would reduce the patient's ability to reach the genital area for self-care.1

In conclusion, the literature tells us that bone fusion should ideally be achieved by posterolateral fixation and anterior fixation using both approaches or an extensive posterior approach only, and that extension of instrumentation to the pelvis or sacrum will lead to increased limitations in mobility for the patient’s daily care, and therefore the choice of the type of patients in whom it is performed should be selective.

Eight of the patients in our series were treated surgically with a wide posterior approach, except one case in whom an anterior approach was also used. Wide instrumentation to the pelvis was not performed in any of the cases. Improvements in stability and neuroautonomic symptoms were found. Even so, it led to the onset of complications such as instrumentation failure, infection, and pressure ulcers in several cases.

Possible complications include instrumentation failure, infection, pressure ulcers, loss of autonomy and/or worsening of the patient's neurological status.1–20 With the intervention, the patient will recover an upright posture but will lose some of the mobility and functionality they had prior to the intervention, and when correcting their posture they will probably require readjustment of their chair and the way they sit may even be affected, with the risk of pressure ulcers at the ischiatic or trochanter level.

Conservative treatment is another option, not only for cases for whom surgery has been ruled out due to associated disease or when the patient refuses surgery. It consists of the use of braces to achieve correct immobilisation, clinical and radiological follow-up, and no aggressive interventions. Authors such as Moreau et al. in 2014 initially proposed conservative treatment and surgery was reserved for patients with persistent symptoms or very unstable cases. From their series of 12 cases, of different aetiologies, as in our series, five of the patients were treated surgically and seven conservatively with a brace for at least three months in three of them, and strict bed rest for two of the patients, and they observed that symptoms had been controlled in five of their patients, there was even complete regression of pain secondary to spontaneous bone fusion in one case. They concluded that in wheelchair-bound or paraplegic patients, loss of autonomy should be considered, and recommended trying braces prior to considering surgery, to assess function if bone fusion was achieved. Furthermore, patients who achieved spontaneous or stable spinal fusion would rarely benefit from surgery.

Haus et al. in 2010, in a series of nine patients, eight treated surgically and one conservatively, found that in 75% of the patients treated surgically severe instability and long-term pain had not been eliminated and even these patients required revision surgery over a period of 14.3 years. Furthermore, 38.3% had a recurrence of Charcot arthropathy in another joint. They concluded that, as the surgery of choice, all three planes of the spine should be stabilised using an anteroposterior or wide posterior approach, but that bone fusion secondary to this stabilisation did not guarantee that instrumentation would not fail or that another Charcot joint would occur in another location and that some patients would benefit temporarily from the use of stabilising braces, although they might have to undergo further surgery.6

Five of the cases of our series were treated conservatively, using a brace for at least three months, with radiographic and consultation follow-up, where disease stabilisation (Fig. 4) and clinical improvement were observed. Pain, spasticity, hyperhidrosis, improved stability, and trunk control disappeared. In addition, our patients did not present complications secondary to this management as had occurred with surgical treatment.

Therefore, we propose the conservative option as a course of action that should be considered from the outset. Hoppenfeld et al. in 1990 and Moreau et al. in 2014 considered whether all Charcot spines required surgery as initial treatment, finding that conservative treatment had a positive effect on instability and back pain.4,19 It was also observed that this treatment is not related to the appearance of other Charcot joints at a later stage4 and that the spinal cord patient usually benefits from this extra mobility at the site of the injury, provided by a kind of functional pseudoarthrosis, to carry out daily activities: transfers, hygiene, bladder catheterisation, enemas. In addition, the patient does not usually have the sensation of a severe problem of stability in their spine.

In conclusion, our line of action would be to consider conservative treatment initially, reserving surgery for cases in which the clinical evolution is not as expected, either due to poor pain control and/or limited mobility secondary to deformity of the trunk, or when the spinal involvement or the clinical presentation of the patient was not tolerated and required a more rapid and aggressive solution.

FundingThis paper has received no funding.

Please cite this article as: Del Arco Churruca A, Vázquez Bravo JC, Gómez Álvarez S, Muñoz Donat S, Jordá Llona M. Artropatía de Charcot en el raquis. Experiencia en nuestro centro. A propósito de 13 casos. Revisión de la literatura. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2021;65:460–467.