Multifocal necrotizing fasciitis is a condition in which there is more than one non-contiguous body area affected, and it is usually the result of the dissemination of septic emboli.

Clinical caseWe present a 67-year-old patient, on oral corticosteroid treatment, who was admitted with a septic shock. During the previous week he had been operated on due to the perforation of a colon diverticulum.

He had signs that suggested necrotizing fasciitis on all four limbs which progressed quickly.

Emergency fasciotomies on all limbs were performed, and empirical antibiotic treatment was started.

ResultsAfter the surgery the patient improved, and seven days after the debridement, primary closure of the wounds was performed. Tissue cultures were negative.

DiscussionBeing a rare entity, there is no consensus regarding the management of multifocal necrotizing fasciitis. However, early and aggressive debridement (including fasciotomies and even amputation) and broad-spectrum antibiotics are essential for its treatment.

La fascitis necrosante multifocal es aquella entidad en la que hay afectada más de un área corporal no contiguas, y que suele ser resultado de la diseminación de émbolos sépticos por vía hematógena.

Caso clínicoPaciente de 67 años, en tratamiento corticoideo oral, que presenta un cuadro de shock séptico. La semana anterior había sido sometido a una intervención de urgencia por la perforación de un divertículo colónico.

Presentaba signos compatibles con fascitis necrosante en las 4 extremidades que evolucionaron rápidamente.

Se decidió la realización urgente de fasciotomías de las 4 extremidades e iniciar tratamiento antibiótico empírico.

ResultadosTras la intervención, el paciente evolucionó favorablemente, y 7 días después del desbridamiento se realizó el cierre primario de las heridas. Los cultivos intraoperatorios fueron negativos.

DiscusiónDebido a su escasa frecuencia, no existe consenso para el manejo de las fascitis necrotizantes multifocales. Sin embargo, se considera esencial el desbridamiento precoz y la antibioticoterapia de amplio espectro.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe infection affecting soft tissues that progresses rapidly, usually involving the limbs. Although the most common entry point is through trauma, there have been some cases described secondary to intestinal perforation.

A much less common occurrence is the onset of multifocal necrotizing fasciitis, referred to an entity in which more than one, non-contiguous body areas are affected, and which is usually caused by the hematogenous dissemination of septic emboli.

Case reportWe present the case of a 67-year-old male patient who was admitted to our hospital with septic shock symptoms. Nine days earlier he had suffered a case of peritonitis secondary to diverticular perforation which had been treated at another center, and which had required resection of the colon at the rectal sigma level, as well as a colostomy (Hartmann intervention). Peritoneal fluid cultures were negative.

The postoperative evolution was correct until, on the ninth day, he began to suffer from hemodynamic instability symptoms, oliguria and disorientation.

Upon arrival, the patient suffered tachycardia, hypotension and significant disorientation. The analysis revealed leukocytosis, with 34,000cells/μl, 79% segmented neutrophils and 8% immature neutrophils. Other levels included lactate 26mg/dl, C reactive protein 28.12mg/dl, sodium 130mEq/l, hemoglobin 9.0g/dl, creatinine 0.92mg/dl and glucose 134mg/dl.

Examination by the general surgery service did not find peritonitis and an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan did not reveal the presence of intraperitoneal fluid or images of abscesses.

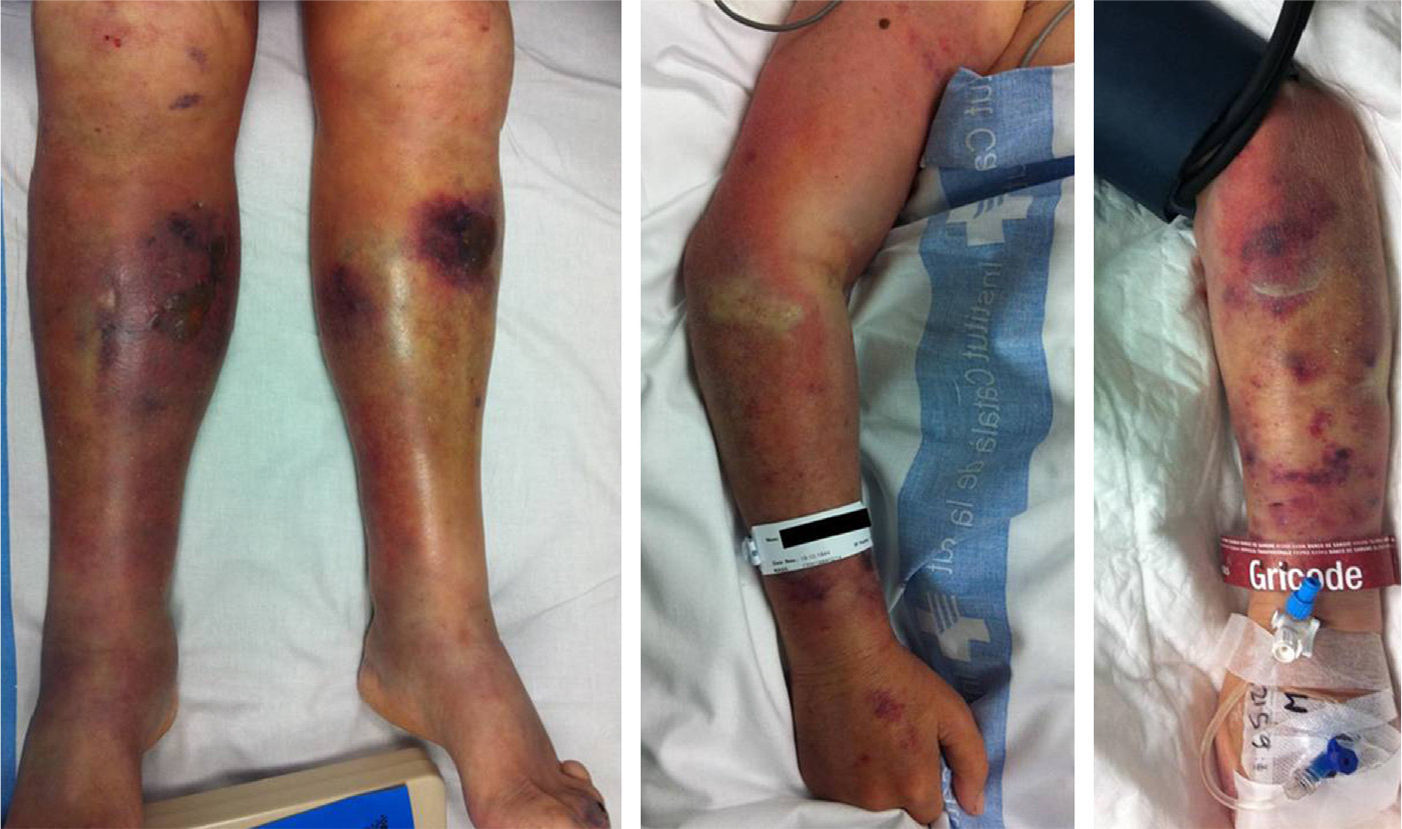

Examination identified purplish lesions on the 2 lower limbs, extending from the feet to the thighs and evolving rapidly, as well as phlyctenas and areas of ecchymosis. In addition, these lesions progressively began to appear in the upper limbs, which initially presented no abnormalities (Fig. 1).

The 4 limbs were swollen and no distal pulses were palpated.

The patient worsened systemically so we began treatment with vasoactive drugs to maintain vital constants.

Given the rapid evolution of the lesions toward all 4 limbs and the systemic deterioration of the patient without any other focus which could explain the shock symptoms, we suspected sepsis secondary to necrotizing fasciitis and opted for urgent surgical intervention.

We carried out urgent surgical debridement, with fasciotomies of all 4 limbs. We identified edema and friability of the subcutaneous tissue, which appeared gray and was easily separated from the underlying fascia, releasing a liquid which appeared like meat washing water. The subfascial musculature appeared viable, with the exception of the deltoid region of the right upper limb.

We collected samples for microbiological culture and anatomopathological assessment.

We initiated broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin 4g/tazobactam 500mg every 8h.

ResultsThe hemodynamic status improved notably during surgery. The patient was admitted into the ICU, where his overall and septic parameters continued to improve. Primary wound closure was performed 7 days after debridement.

Intraoperative cultures taken during the first surgery were negative.

DiscussionNecrotizing fasciitis is caused by the proliferation of a microorganism on the surface of the fascia. The specific mechanism of proliferation is not completely clear, but it is attributed to liquefactive necrosis caused by the action of bacterial enzymes, such as cytokines, toxins and hyaluronidase. The subcutaneous tissue undergoes ischemic necrosis due to vessel obturation.1

The clinical manifestations include swelling, rapidly spreading cellulitis, severe pain and even palpable crepitus if the causative germ is anaerobic. The patient may suffer septic shock.

The definitive diagnosis is obtained through surgical exploration,2 where the characteristic findings include gray, edematous, subcutaneous fat which is easily separated from the fascia by blunt dissection, fascia which do not bleed and the presence of a gray liquid with a fetid smell (meat washing water) throughout the fascial plane.3

Necrotizing fasciitis is traditionally classified into type I (polymicrobial/synergistic) and type II (monomicrobial, generally caused by a gram-positive germ). The majority of fasciitis cases are secondary to polymicrobial infections.1

Negative cultures (both blood cultures and intraoperative tissue samples) do not rule out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. In a series of 89 fasciitis, Wong et al.4 obtained negative results in 18% of cases, often linked to the start of empiric antibiotic therapy before samples were taken. Other diagnostic tests, such as detection through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) upon suspicion of a particular bacteria (like group A streptococcus), have shown greater sensitivity but are not routinely performed at our center.2

The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is determined upon the observation of soft tissue edema and necrosis at the time of surgery, and when the histopathological analysis finds necrosis of the superficial fascia, with fascial edema and polymorphonuclear infiltrate.3

It can be difficult to identify the symptoms preoperatively, especially in acute and subacute variants of necrotizing fasciitis, since they have a very fast evolution which leaves little time for the onset of typical cutaneous signs, and we may find a patient suffering septic shock and multiorgan failure with relatively well-preserved skin.5

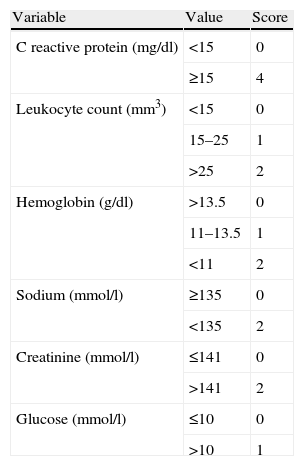

In order to help distinguish between necrotizing fasciitis and other soft tissue infections, Wong et al6 developed a scoring system based on laboratory parameters, known as Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) (Table 1). Scores of 8 or more points are considered as strong predictors of necrotizing fasciitis (positive predictive value of 93.4%).

The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) test is a tool developed to facilitate the distinction between necrotizing fasciitis and other soft tissue infections.

| Variable | Value | Score |

| C reactive protein (mg/dl) | <15 | 0 |

| ≥15 | 4 | |

| Leukocyte count (mm3) | <15 | 0 |

| 15–25 | 1 | |

| >25 | 2 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | >13.5 | 0 |

| 11–13.5 | 1 | |

| <11 | 2 | |

| Sodium (mmol/l) | ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 | |

| Creatinine (mmol/l) | ≤141 | 0 |

| >141 | 2 | |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | ≤10 | 0 |

| >10 | 1 |

By establishing a cut-off point of ≥6 points we obtain a positive predictive value of 92%, and with a cut-off point of ≥8 points, of 93.4%.

Necrotizing fasciitis can affect any part of the body but is most common in the abdominal wall, limbs and perineum. It is often not possible to discern the entry point of the pathogen, although the most common are lesions in the affected limb, with a traumatic, infectious (like varicella) and even iatrogenic origin (from vaccine inoculation points to surgical wounds).1 There have also been reports of the onset of necrotizing fasciitis symptoms in the lower limbs secondary to peritonitis, in which the pathogen moved to the leg through the femoral canal or sciatic nerve.7

Once bacteremia has appeared, hematogenous metastatic deposition of septic emboli may take place and this can result in more than one area of non-contiguous necrosis (multifocal necrotizing fasciitis).

This entity is associated with a 39–70% mortality rate; higher than that of unifocal fasciitis.8 There are very few clinical series in the literature dealing with multifocal fasciitis, but they are apparently linked to the presence of a single germ (type ii necrotizing fasciitis). This is the opposite scenario of unifocal fasciitis, where type i cases account for 80% and type ii for only 20%. This could be due to the fact that type ii necrotizing fasciitis is usually much more aggressive in its progression: considering that bacteremia and toxic shock are more likely to appear in type ii fasciitis, we can extrapolate that the metastasis of septic emboli is also more likely to occur in type ii cases.

Due to its rarity, there is no consensus on the management of multifocal necrotizing fasciitis. However, certain approaches, such as early and aggressive debridement (including fasciotomies and, in some cases, even amputation) and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, are considered essential.

Surgical debridement should not await the result of blood cultures or skin smear tests. Clinical suspicion should take precedence.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Navarro-Cano E, Noriego-Muñoz D. Fascitis necrosante multifocal. A propósito de un caso. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:60–63.