To assess the health related quality of life (HRQOL) and associated factors of patients before, and one year after, total knee (TKA) and hip (THA) arthroplasty.

MethodsA quasi-experimental prospective study conducted in hospitals with different levels of complexity and volume in Catalonia, and on patients (n=672) with an indication of a TKA or THA. Demographic and psychosocial variables were recorded, and the SF-36 and WOMAC, and a questionnaire on perception of change after surgery were administered to patients by telephone interview. The standardised differences (effect size) of perceived change using the SF-36 and WOMAC scores before and after surgery were calculated. The factors associated with HRQOL one year after surgery were analysed using adjusted general linear models.

ResultsAlthough there was an overall improvement in most HRQOL domains, 9% saw little improvement after surgery, with their scores at baseline and follow-up being very similar (small size effect: 0.0–0.4). Women, patients with low social support, with lower scores (worse) in perceived mental health and baseline HRQOL, and who declared that their condition was more severe, perceived a poorer HRQOL one year after surgery (P<.05).

ConclusionsFactors associated to a worse prognosis one year after an arthroplasty have been identified and are consistent with other published studies. The assessment of HRQOL can be a key instrument for identifying possible patients without improvement, in order to assess alternatives to an intervention, or apply other interventions in order to improve the efficiency of the healthcare process.

Evaluar la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) de los pacientes antes y después de su artroplastia total de rodilla (ATR) y cadera (ATC) y los factores relacionados al año.

MetodologíaEstudio prospectivo cuasi-experimental. Se seleccionaron hospitales de diferente nivel de complejidad y volumen en Cataluña y pacientes con indicación de ATC o ATR. Se administraron el SF-36 y el WOMAC, variables demográficas, psicosociales y una pregunta sobre percepción de cambio a los pacientes por entrevista telefónica. Se calcularon las diferencias estandarizadas en las puntuaciones del SF-36 y WOMAC antes y después de la cirugia (tamaños del efecto, TE) según percepción de cambio. Se analizaron factores relacionados con la CVRS al año a partir de modelos lineales generales ajustados.

ResultadosA pesar de que a nivel global, los pacientes (n=672) presentaron mejoría en la mayoría de dimensiones de CVRS, un 9% percibió poca mejoría al año, siendo sus puntuaciones muy parecidas en el basal y seguimiento (TE pequeñas: 0,0-0,4). Las mujeres, pacientes con bajo apoyo social, con puntuaciones más bajas (peores) en la salud mental percibida y CVRS basal, y que declaran que su enfermedad es más grave percibieron peor CVRS al año (p<0,05).

ConclusionesSe han identificado factores relacionados con peor pronóstico de la artroplastia consistentes con otros estudios publicados. La valoración de la CVRS puede ser un instrumento clave para identificar casos de posible no mejora y poder valorar alternativas o aplicar alguna intervención previa y mejorar así la eficiencia del proceso asistencial.

The most commonly used strategy to measure the clinical effectiveness of arthroplasties is survival of the prosthesis, generally defined as the period elapsed from the time when the patient underwent a primary arthroplasty and the prosthesis was implanted until another intervention was required to replace the faulty prosthesis. Thus, international arthroplasty registers, which include monitoring of the majority of the population attended in a given territory or country, usually incorporate survival of the implant as a primary result in the medium and long term.1 In addition to this indicator of healthcare quality, other performance indicators are commonly used in the field of traumatology and orthopaedic surgery.2 Scandinavian registers, such as the Swedish Arthroplasty Register, measure the level of patient satisfaction with the intervention, mortality at 90 days, improvements in pain and functional capacity 1 year after the arthroplasty.3–5

In spite of the advantages of measuring clinical effectiveness based on prosthesis survival, in terms of robustness and credibility in the field of traumatology, this approach does not include the perspective of users regarding assessment of healthcare quality nor a comprehensive assessment of the benefits of surgery.6 The use of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measurements or other measurements of patient perception, Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS), can offer a broader view of the healthcare problem under study. The incorporation of these tools helps to describe the groups of patients with problems in one or more health dimensions, identifying those patients whose pain, functional limitations or symptoms do not improve after surgery, with the ultimate goal of facilitating clinical planning and decision making.7 In addition to the Swedish register and other international registers, the United Kingdom8 is an example of the extended use of these HRQoL measures. Since 2008, the National Health Service (NHS) routinely collects information reported by users for all publicly funded hip and knee arthroplasty interventions. The objective of these measurements is to assess the quality of care, seeking a healthcare model which is more focused on patients (in short, healthcare services which are adapted to the expectations of patients and their families, respecting their values and beliefs, and a greater participation alongside physicians in the decision-making process).

In operational terms, HRQoL includes the measurement of general health, functional physical, emotional and social status, cognitive function and physical and mental symptoms. The most widespread definition of HRQoL presents a multidimensional perspective of health, which includes the perspective of patients and individuals regarding their health and general welfare status, as well as the influence it has on their own ability to carry out activities considered important by the individuals themselves.9 The extension of their use and application in different contexts10 and the dissemination of results could improve understanding of HRQoL results, as well as the application of these instruments for the management of patients.

Recent studies have reported that a worse HRQoL score prior to surgery, as well as a worse score for anxiety/depression and other factors related to patient characteristics, have an influence on a worse outcome of hip and knee surgery.8,11–14

In the area of Catalonia, despite having a population registry like the Catalan Arthroplasty Registry (RACat) to evaluate the effectiveness of arthroplasties and describe the variability in the use of implants in this field, there were no recent multicentre data regarding prospective measurements of HRQoL. It is for this reason that the present project was initiated, in order to complement the information on the clinical effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA), and identify the most relevant factors related to HRQoL, for their possible inclusion in a population-based registry. The main objective of this study is to describe the HRQoL of patients undergoing TKA and THA in 7 public hospitals in Catalonia, before and after arthroplasty, as well as factors related to the scores 1 year after the intervention.

MethodologySample selection and designThis was a prospective, quasi-experimental (before–after) study in which each patient was followed-up by a telephone interview before and 1 year after undergoing THA or TKA (January 2007–July 2008). For the sake of convenience, we selected 7 public hospitals with a different level of healthcare and volume of activity. Collaboration from the Traumatology and Orthopaedic Surgery (COT) services was requested, along with informed consent forms from patients, in order to enter the study and conduct a telephone interview on 2 separate occasions (before and 1 year after surgery). COT services collected informed consent forms permitting telephone interviews by Sanitat Respon (Medical Emergencies Service). We expected a response rate of around 60% for the telephone interviews. We selected patients scheduled for THA and TKA interventions. The exclusion criteria were urgent interventions, having to undergo surgery for replacement arthroplasty or partial hip arthroplasty, having a diagnosis of fracture or malignant bone tumour, and interventions on patients under 18 years of age. We also excluded patients with organic or psychiatric conditions which prevented their collaboration in the study (generally representing criteria preventing arthroplasty interventions), and patients who suffered sensory deficits (being deaf and/or mute) which prevented them from completing the questionnaires administered by telephone. We ruled out the possibility of conducting interviews with direct informers (e.g. relatives).

Study instruments and variablesWestern Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis IndexThe Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) questionnaire is a specific HRQoL tool for patients with osteoarthritis, which includes a total of 24 items. In the present study we used the dimensions (functional capacity, pain and stiffness), which included a range of scores from 0 to 100, with a lower score indicating a better HRQoL.15,16

Short Form-36 Healthcare QuestionnaireThe Short Form-36 (SF-36) is a generic, HRQoL questionnaire which can be applied in different groups, regardless of the health problem under study. It includes a total of 36 items grouped into 8 dimensions (physical function, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, emotional role and mental health). The scores can be standardised with a range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a better HRQoL.17,18

Both the WOMAC and the SF-36 questionnaires have shown adequate sensitivity values to detect changes in HRQoL after an intervention. The present study described HRQoL scores at baseline (before surgery) and after 1 year (post-intervention). The baseline scores in the mental health dimension of the SF-36 (range: 0–100) were recoded from scores into tertiles: low (<40), medium (40–70) and high (>70) mental health.

DUKE Social Support ScaleThis questionnaire includes a total of 9 items grouped into 3 scales which give a total score for social support; with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support.19 Social support was recoded from scores into tertiles: low (<33), medium (33–39) and high (>39) social support.

Sociodemographic variablesWe collected information on gender, age at the time of interview (continuous), people who the patient lived with, whether they received help for daily tasks (yes, no), whether they had dependents (yes, no) and their educational level (regrouped into primary or less, secondary and university).20

Other variables related to health status and use of health servicesWe collected information on the type of arthroplasty (hip or knee), about hospital readmissions due to the arthroplasty which motivated the study (yes, no), previous arthroplasties (no, yes), perceived severity (very severe, quite severe, severe, scarcely-not severe) and on the overall perception of change at 1 year of surgery (adapted from the SF-36 “Compared to your condition before hip or knee surgery, how is your hip or knee problem currently?” with 5 possible answers: much better, somewhat better or only slightly better now than 1 year ago, about the same as 1 year ago, somewhat or much worse now than 1 year ago). These categories were regrouped into: considerable improvement (much better, somewhat better), some improvement (only slightly better) and no improvement (about the same, somewhat or much worse now than 1 year ago).

Statistical analysisWe calculated standardised differences in SF-36 scores before and after surgery (effect size) overall and according to the perception of change. We compared the effect size of the dimensions of this questionnaire regarding HRQoL in patients who reported being much better compared to those who did not improve after surgery. Effect size values >0.8 were considered considerable differences in scores, values between 0.6 and 0.8 were considered moderate differences, and values between 0.2 and 0.5 were considered small differences. Differences less than 0.2 were considered as null differences in HRQoL scores. We computed a general linear model (GLM) for each dimension 1 year after surgery (for example, postoperative physical function as a dependent variable), introducing each independent variable considered in the model (for example, gender) adjusted for the remainder of demographic, psychosocial and health variables of patients (age, educational level, requiring help to perform daily tasks, having dependents, social support, type of arthroplasty, previous arthroplasties, perceived severity), and baseline HRQoL (if the GLM for postoperative physical function was computed, then we introduced continuous, preoperative physical function) and, lastly, baseline mental health measured from the SF-36.

Statistical analyses were performed using the software package SPSS®.

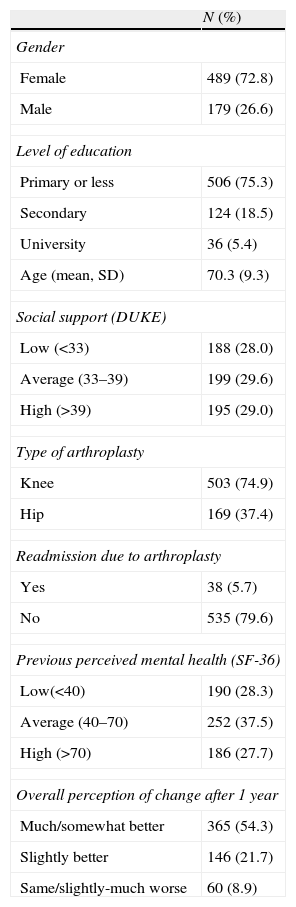

ResultsCharacteristics of participantsWe conducted the baseline interview before surgery on 922 patients, and an interview 1 year later on 956 patients (a response rate of 60%, compared to the 1549 patients recruited with informed consent). A total of 672 patients were able to respond to both telephone interviews (baseline and follow-up after 1 year). Of the 672 patients finally included in the analysis, 73% were female, 75% had primary education or less and a mean age of 70 years at the time of the baseline interview. Most patients underwent TKA (75%), 54% reported feeling much better 1-year after surgery, 22% somewhat better, and 9% felt they had not improved (Table 1).

Characteristics of the patients included in the study (n=672).

| N (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 489 (72.8) |

| Male | 179 (26.6) |

| Level of education | |

| Primary or less | 506 (75.3) |

| Secondary | 124 (18.5) |

| University | 36 (5.4) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 70.3 (9.3) |

| Social support (DUKE) | |

| Low (<33) | 188 (28.0) |

| Average (33–39) | 199 (29.6) |

| High (>39) | 195 (29.0) |

| Type of arthroplasty | |

| Knee | 503 (74.9) |

| Hip | 169 (37.4) |

| Readmission due to arthroplasty | |

| Yes | 38 (5.7) |

| No | 535 (79.6) |

| Previous perceived mental health (SF-36) | |

| Low(<40) | 190 (28.3) |

| Average (40–70) | 252 (37.5) |

| High (>70) | 186 (27.7) |

| Overall perception of change after 1 year | |

| Much/somewhat better | 365 (54.3) |

| Slightly better | 146 (21.7) |

| Same/slightly-much worse | 60 (8.9) |

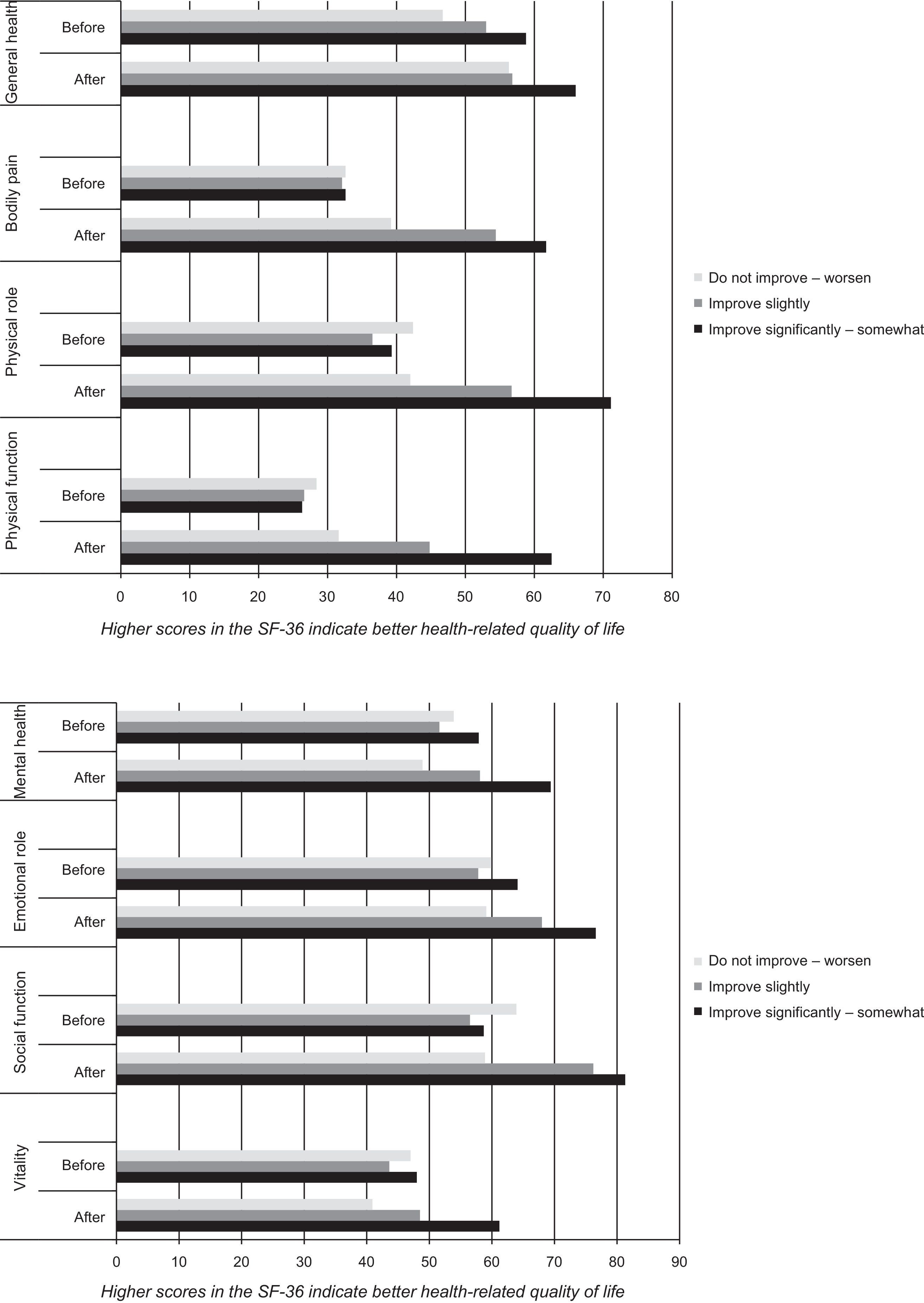

Overall, patients improved their HRQoL 1 year after surgery, presenting elevated standardised differences (effect size >0.8) in their scores 1 year after surgery in all dimensions of the WOMAC scale, both for knees (effect size: 1.2–1.7) and for hips (effect size: 1.5–1.8); the latter data are not shown. In the case of the SF-36 and in the group of patients who felt much-somewhat better after surgery (Fig. 1), we observed elevated standardised differences (effect size >0.8) between the scores before and 1 year after surgery in physical health dimensions (physical function, physical role and bodily pain), and moderate differences in social function (effect size: 0.6). In the group of patients who perceived some improvement, we observed a moderate effect size (0.8) in physical function and elevated effect size (0.9) in bodily pain. The remaining dimensions of the SF-36 showed little or no differences (effect size <0.2) in scores before and after surgery in this group who perceived some improvement. Finally, we observed little or no differences in all dimensions of the SF-36 in the group of patients who perceived no improvement at 1 year after surgery.

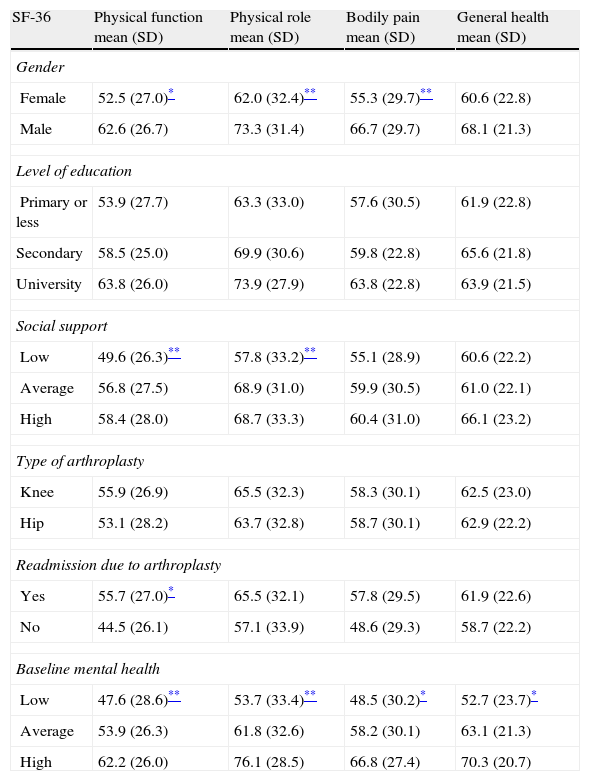

Tables 2 and 3 show the factors associated with the adjusted scores of the SF-36 and WOMAC scales 1 year after arthroplasty. Females presented lower (worse) HRQoL scores in most dimensions of the SF-36 1 year after surgery, compared to males (P<.05). Patients with a primary education level or less also presented lower scores (worse) in social role (limitations in activities due to health problems) 1 year after surgery (P<.05). On the other hand, patients who reported low social support presented lower scores (worse) in their physical function, physical role, vitality, emotional role and mental health of the SF-36 1 year after the arthroplasty. In the present study, no dimension of the SF-36, showed a statistically significant association with the type of arthroplasty (knee or hip) or the presence of previous operations. Requiring hospital readmission due to the surgery was associated to lower scores (worse) in physical function, vitality and emotional role in the SF-36. Lastly, lower scores in baseline perceived mental health were associated with worse HRQoL scores after 1 year in all dimensions of the SF-36 (P<.05). In addition to prior mental health, baseline HRQoL was associated in a statistically significant manner with HRQoL 1 year after the TKA and THA in all dimensions of the SF-36.

Factors related to scores in the SF-36 questionnaire 1 year after surgery (n=672).a

| SF-36 | Physical function mean (SD) | Physical role mean (SD) | Bodily pain mean (SD) | General health mean (SD) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 52.5 (27.0)* | 62.0 (32.4)** | 55.3 (29.7)** | 60.6 (22.8) |

| Male | 62.6 (26.7) | 73.3 (31.4) | 66.7 (29.7) | 68.1 (21.3) |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary or less | 53.9 (27.7) | 63.3 (33.0) | 57.6 (30.5) | 61.9 (22.8) |

| Secondary | 58.5 (25.0) | 69.9 (30.6) | 59.8 (22.8) | 65.6 (21.8) |

| University | 63.8 (26.0) | 73.9 (27.9) | 63.8 (22.8) | 63.9 (21.5) |

| Social support | ||||

| Low | 49.6 (26.3)** | 57.8 (33.2)** | 55.1 (28.9) | 60.6 (22.2) |

| Average | 56.8 (27.5) | 68.9 (31.0) | 59.9 (30.5) | 61.0 (22.1) |

| High | 58.4 (28.0) | 68.7 (33.3) | 60.4 (31.0) | 66.1 (23.2) |

| Type of arthroplasty | ||||

| Knee | 55.9 (26.9) | 65.5 (32.3) | 58.3 (30.1) | 62.5 (23.0) |

| Hip | 53.1 (28.2) | 63.7 (32.8) | 58.7 (30.1) | 62.9 (22.2) |

| Readmission due to arthroplasty | ||||

| Yes | 55.7 (27.0)* | 65.5 (32.1) | 57.8 (29.5) | 61.9 (22.6) |

| No | 44.5 (26.1) | 57.1 (33.9) | 48.6 (29.3) | 58.7 (22.2) |

| Baseline mental health | ||||

| Low | 47.6 (28.6)** | 53.7 (33.4)** | 48.5 (30.2)* | 52.7 (23.7)* |

| Average | 53.9 (26.3) | 61.8 (32.6) | 58.2 (30.1) | 63.1 (21.3) |

| High | 62.2 (26.0) | 76.1 (28.5) | 66.8 (27.4) | 70.3 (20.7) |

| SF-36 | Vitality mean (SD) | Social role Mean (SD) | Emotional role Mean (SD) | Mental health Mean (SD) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 53.6 (25.6)* | 77.0 (30.2) | 70.7 (31.2) | 62.0 (24.7)* |

| Male | 66.6 (22.8) | 84.6 (24.9) | 81.5 (28.0) | 75.6 (21.8) |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary or less | 56.0 (26.1) | 78.4 (29.1)* | 71.2 (31.4) | 63.4 (25.3) |

| Secondary | 61.2 (24.4) | 78.7 (31.2) | 79.5 (28.3) | 72.1 (21.7) |

| University | 59.9 (19.4) | 88.5 (21.2) | 85.4 (22.9) | 74.3 (20.1) |

| Social support | ||||

| Low | 49.9 (26.0)* | 72.2 (33.5) | 65.2 (31.8)** | 58.3 (24.9)** |

| Average | 57.7 (24.0) | 81.8 (25.6) | 75.6 (28.6) | 67.5 (22.3) |

| High | 62.7 (25.5) | 82.1 (27.2) | 81.2 (29.3) | 70.9 (25.0) |

| Type of arthroplasty | ||||

| Knee | 57.1 (26.0) | 79.0 (29.2) | 72.5 (31.0) | 65.0 (24.8) |

| Hip | 57.1 (24.6) | 79.4 (29.2) | 77.3 (29.4) | 68.1 (24.3) |

| Readmission due to arthroplasty | ||||

| Yes | 56.5 (24.8)** | 78.4 (35.6) | 73.3 (30.5)** | 64.9 (24.4) |

| No | 52.3 (26.6) | 71.4 (35.5) | 65.1 (34.3) | 63.0 (25.7) |

| Baseline mental health | ||||

| Low | 44.1 (24.1)* | 67.2 (34.7)* | 53.3 (32.4)* | 48.7 (23.4)* |

| Average | 55.3 (23.3) | 79.0 (28.4) | 77.5 (27.0) | 66.3 (20.5) |

| High | 68.9 (23.3) | 89.4 (19.8) | 87.3 (23.5) | 78.9 (21.4) |

SD: standard deviation.

Higher scores in the SF-36 indicate a better health.

Factors related to scores in the WOMAC questionnaire 1 year after surgery (n=672).a

| WOMAC | Pain mean (SD) | Rigidity mean (SD) | Functional capacity mean (SD) | Overall WOMAC mean (SD) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 19.3 (18.4)* | 18.9 (21.6) | 23.2 (18.5) | 21.9 (17.5) |

| Male | 13.5 (16.4) | 15.4 (19.5) | 19.6 (19.6) | 18.2 (18.5) |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary or less | 18.2 (18.2) | 17.5 (29.7) | 22.5 (19.0) | 21.2 (17.8) |

| Secondary | 17.1 (18.1) | 20.7 (23.4) | 22.4 (18.8) | 21.2 (18.4) |

| University | 12.6 (13.9) | 11.8 (14.9) | 16.9 (16.5) | 15.5 (15.2) |

| Social support | ||||

| Low | 19.5 (18.0) | 20.3 (21.2) | 25.7 (18.4)** | 24.0 (17.6) |

| Average | 17.6 (18.0) | 17.5 (21.0) | 21.2 (18.6) | 20.2 (17.5) |

| High | 16.3 (18.7) | 16.1 (21.7) | 20.2 (19.6) | 18.9 (18.6) |

| Type of arthroplasty | ||||

| Knee | 18.2 (18.0) | 18.4 (21.4) | 22.0 (18.8) | 20.9 (17.9) |

| Hip | 16.2 (18.1) | 16.6 (20.4) | 23.3 (19.0) | 21.1 (17.7) |

| Readmission due to arthroplasty | ||||

| Yes | 17.1 (17.1) | 17.8 (20.8) | 21.8 (18.3) | 20.5 (17.3) |

| No | 24.9 (23.5) | 26.6 (27.0) | 30.1 (18.8) | 27.9 (18.2) |

| Baseline mental health | ||||

| Low | 23.0 (20.5)** | 22.9 (24.4)* | 28.0 (21.0)** | 26.8 (20.3)** |

| Average | 18.1 (17.1) | 18.8 (20.0) | 23.7 (19.0) | 22.4 (17.8) |

| High | 13.1 (15.2) | 13.1 (17.7) | 16.3 (15.3) | 15.1 (14.2) |

SD: standard deviation.

Lower scores in the WOMAC indicate better health.

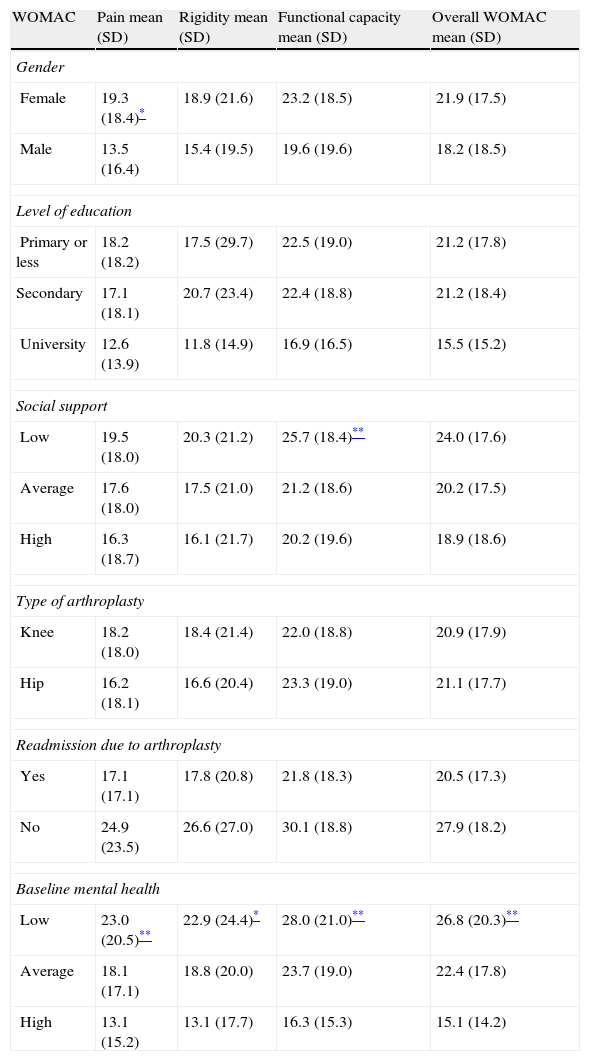

In the case of scores on the specific WOMAC questionnaire 1 year after surgery, we observed statistically significant differences according to gender, social support and perceived mental health in baseline HRQoL. Females presented higher scores (worse) in pain after arthroplasty, compared to males (P<.01). Patients who reported having low social support, presented worse scores in functional capacity compared to patients with high social support (P<.05). Finally, patients with low baseline perceived mental health (measured from the SF-36) presented higher scores (worse) in all WOMAC dimensions, including overall HRQoL score.

DiscussionAlthough most patients perceived improvement at 1 year after surgery, 9% of the subjects in this study reported feeling the same or worse and 22% perceived scarce improvement. HRQoL scores in these patient groups were similar at baseline and 1 year after surgery. Thus, there is evidence that females, people with primary education level and low social support, as well as those who perceive more severity and worse mental health prior to surgery, presented a poorer HRQoL 1 year after the arthroplasty in this study. These results are consistent with those of other published studies.11–13,20–22 A study of the Swedish knee registry noted that anxiety/depression measured from the EQ-5D represented a predictive factor of pain relief and patient satisfaction with the care received in the medium term.5,13 Like the SF-36, the EQ-5D is a generic HRQoL questionnaire which can be administered to users suffering different health problems and also to a healthy population, in order to compare scores with normal values, as well as conducting cost effectiveness studies. Other studies in the Basque Country and Catalonia11,12,20 have revealed similar results to the SF-36 and WOMAC instruments, showing the usefulness of measuring patient perception in order to deepen knowledge about health needs of patients requiring orthopaedic surgery and to study factors related to a better/worse prognosis.

HRQoL includes a holistic and complex concept, pointing out the possible interrelationship between the different health dimensions (physical, psychological and social). For this reason, it is important to describe and interpret HRQoL scores in different groups, identifying those patients or subgroups with most healthcare needs. Detection of unmet health needs (HRQoL scores below the expected threshold) would imply the relevance of other interventions to improve the health status of these patients, in addition to prosthetic surgery. Since we did not record the mental health diagnosis, but rather the perceived mental health and emotional role, we cannot know whether poor physical health (arthritis, pain and functional limitation) led to a worse mental health or limitation of social activities, or if comorbidity was present prior to the surgery. This would require further, in-depth studies, in order to understand the mechanisms linking perceived mental health with improvements or lack thereof in HRQoL after arthroplasty.

Studies with a quasi-experimental design are most commonly used to measure the effectiveness of hip and knee arthroplasties, based on measurements of perception by patients in a national and international context. This type of assessment-based design shares characteristics with an experimental methodology (exposure to an intervention, response and hypothesis to be verified), but unlike in randomised clinical trials, there is no random assignment of patients to treatments.22 The quasi-experimental design enables the analysis of factors related to postoperative improvement in terms of HRQoL, allowing selection of patients in routine clinical practice conditions to study the effectiveness of surgery. It should be noted that, since it is not an experimental design, and no control group was selected in the present study, there are limitations in the attribution of changes in HRQoL to the intervention itself. Future studies should take into account the inclusion of other types of patients and control groups (e.g. patients not undergoing surgery or with partial hip surgery) in order to compare their HRQoL scores with those of patients undergoing THA or TKA. It would also be interesting to study the relationship of other clinical variables with HRQoL after arthroplasty, such as the surgical risk of ASA, the body mass index and the presence of comorbidities. In addition to patient characteristics and previous health, other factors, such as the type of implant and hospital,23 have been associated with better performance of surgery in terms of improvement perceived by patients.

It is important to mention some additional limitations of the study. In relation to the sample and how representative it was, we recruited fewer patients than expected, especially in the case of patients with an indication of THA. The consequences of epidemiological changes in this type of surgery at the start of the study led to increased difficulties in recruiting patients requiring THA. In most studies, losses during follow-up are attributed to patients with worse health conditions. In our study, these potential selection biases could have introduced an overestimation of the benefit of THA and TKA in terms of improvement in HRQoL, by including patients with better health and less severe conditions. Despite these limitations, the study was able to show that the characteristics of the baseline and postoperative samples were similar to those of the final sample of patients, with both telephone interviews (in terms of distribution by gender, type of joint, educational level and scores on the WOMAC and SF-36 scales).

In conclusion, apart from the quality of healthcare indicators which measure clinical effectiveness and safety of arthroplasties, such as prosthesis survival and complications during or after surgery, it is also important to measure aspects of care focused on patients. Such results would enable us to analyse which groups of patients do not improve in terms of pain, functional capacity and physical and emotional well-being. It is also worth mentioning that a possible impact of the results of the present study is that, in addition to prosthetic surgery, it would be advisable to take into account complementary interventions which helped to improve the performance of surgery, or to review the criteria or the indication of an arthroplasty among those patients whose HRQoL would benefit less. The results indicate that the planning of healthcare resources for elderly patients, especially females, in addition to the perception of physical health, should also take into account perceived mental-emotional and social health in patients requiring THA or TKA. The application of patient perception measurements in clinical practice would enable us to gather valuable information for decision-making.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThis work was financed by the Healthcare Research Fund (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria) (PI052850 and PI1100166).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The research team wishes to thank all those professionals who participated in the recruitment of patients, as well as other researchers from FIS, for their collaboration in the project. They also wish to thank all the patients for their invaluable collaboration by dedicating their time to this study.

Josep Riba (clinical coordinator, Hospital Clínico de Barcelona); Xavier Chornet (clinical coordinator, Hospital Comarcal de Blanes); Joan Leal (clinical coordinator, Parc de Salut Mar); Marta Riu (coordinator, Parc de Salut Mar); Moisès Coll (clinical coordinator, Hospital de Mataró); Jordi Ramón (clinical coordinator, Hospital de Sabadell); Enric Castellet (clinical coordinator, Hospital de la Vall d’Hebrón); Vicky Serra-Sutton (researcher-coordinator, AQuAS); Alejandro Allepuz (researcher, AQuAS); Olga Martínez (support technician, AQuAS), and Mireia Espallargues (principal researcher, FIS, AQuAS).

Please cite this article as: Serra-Sutton V, Allepuz A, Martínez O, Espallargues M. Factores relacionados con la calidad de vida al año de la artroplastia total de cadera y rodilla: estudio multicéntrico en Cataluña. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:254–62.

Annex 1 contains the names of the members of the Working Group for the Evaluation of Arthroplasties in Catalonia.