The purpose of this study is to assess the need to lock the Gamma 3 nail (Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA) distally for intertrochanteric fractures of femur 31-A1 and 31-A2 of the AO.

Materials and methodsDetails were recorded on a sample of 177 patients with intertrochanteric femoral fractures treated in our hospital by a standard Gamma nail between June 2011 and January 2013. A prospective study was conducted by randomizing patients by year of birth, even numbers with, or odd numbers without, and distal locking, forming two groups of 90 and 87 fractures, respectively.

ResultsThe patients treated with a distal locking nail had an increased incidence of medical complications, a lower incidence of biomechanical complications, and an increase in the fracture collapse compared with the control group, with statistical significance (P<0.05). It is also observed in the group that distal locking increased transfusion requirement and a higher death rate, with statistically significant differences (P<0.05), but this significance disappears when adjusting for other patient-related characteristics.

ConclusionsBased on the results found in this work, the use of distal locking screw in the Gamma 3 nails should be restricted to unstable trochanteric fractures after reduction where additional stability to the intramedullary nail is required, and may decrease the risk of complications from use.

El propósito de este estudio es valorar la necesidad de bloquear distalmente los clavos Gamma 3 (Stryker. Mahwah, New Jersey. USA) en fracturas pertrocantéreas de fémur 31-A1 y 31-A2 de la AO.

Material y métodosDesde junio de 2011 hasta enero de 2013 se recoge una muestra formada por 177 pacientes con fractura pertrocantérea de fémur tratados en nuestro centro mediante osteosíntesis con clavo Gamma 3 estándar. Es un estudio prospectivo y aleatorizado según el año de nacimiento de cada paciente, par con bloqueo o impar sin bloqueo distal del clavo, formando dos grupos de 90 y 87 fracturas respectivamente.

ResultadosEn los pacientes intervenidos mediante clavo con bloqueo distal se observó una mayor incidencia de complicaciones médicas, una menor incidencia de complicaciones biomecánicas y un aumento en el colapso del foco de fractura en comparación con el grupo control, siendo estas diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p<0,05). También se observa en el grupo con bloqueo distal un mayor requerimiento transfusional y una mayor tasa de éxitus presentando diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p<0,05), sin embargo esta significación desaparece al ajustar los resultados por otras características relacionadas con los pacientes.

ConclusionesBasándonos en los resultados hallados en este trabajo, el uso del tornillo de bloqueo distal en los clavos Gamma 3 debe restringirse a fracturas pertrocantéreas inestables tras reducción donde se requiera una estabilidad adicional al clavo intramedular, pudiendo así disminuir el riesgo de complicaciones derivadas de su uso.

Intertrochanteric femoral fractures account for about 55% of fractures in the proximal segment of the femur and their incidence has increased in recent years due to gradual population aging. These pathologies have become commonplace in Traumatology and Orthopedic Surgery Services like ours, with an annual mean of 196 interventions (range: 168–243) of these type of fractures during the period between 2005 and 2013.

Intramedullary nailing is the first line of treatment in these fractures, as it offers a shorter surgery time, less aggression on soft tissues and considerable stability due to its reduced lever arm compared to sliding plate-screw systems, thus enabling early mobility and load in most cases.1–5 Intramedullary devices have evolved in order to reduce complications, improve results and facilitate surgical techniques.6 One example is the Gamma 3 nail (Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA), which, unlike its predecessor, the trochanteric Gamma nail (TGN), presents a valgus of 4°, reduced transversal diameter (11mm) and shorter length (180mm), thereby offering a more anatomical design which simplifies its use.3

The complications associated to intramedullary osteosyntheses with this type of nails have been well documented since they began to be used in the 70s. One such source of complications is the placement of distal blocking screws, which account for 10–13% of the total depending on the series,2,7 especially in cases of screws with diameters of 6mm or more.6,8 The complications described include intra- and postoperative diaphyseal femoral fractures caused by a weakening of the cortices and excessive rigidity in the tip of the nail,1,6,8–12 irritation of the fascia lata at the site of insertion,13 nonunion with femoral malrotation, implant tears (due to increased stress caused by the neutralization of loads on the facture focus in nails with distal blocking or by notches on the orifices of the nail for the blocking screw during its introduction which decrease the resistance of the implant by 50–80%),2,10,13,14 malposition of the blocking screw,6 stress-shielding phenomena11,15 and aneurisms of the femoral artery.16,17 According to some published works, such as the biomechanical studies by Rosenblum et al. and Mahomed et al.10 distal blocking increases the tension at the tip of the nail, where all the loads are transmitted when standing, and may increase the risk of collapse of the fracture, stress-shielding phenomena and cut-out effects, due to an excessive rigidity of the assembly.2,6,10,11,14,15

According to the technical datasheet, implantation of a nail with distal block is indicated in cases of unstable fractures where rotational stability is required or when there is a considerable difference between the diameter of the nail and the femoral medullar cavity. Unstable intertrochanteric fractures are those which present comminution of a large posteromedial fragment, an inverse oblique fracture pattern and those in which a correct reduction of the calcaneal or medial cortical cannot be achieved.18

However, literature in this respect is scarce and there are many different opinions regarding application. Some authors implant Gamma nails with a distal block systematically3,6,7,19,20 or do not specify their use,2,6,11,12,21 so most series are very heterogeneous and include intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric femoral fractures. Nevertheless, other authors suggest that the use of distal blocking should be restricted to cases of unstable fractures following reduction.4,13,15,18 In the literature review conducted, only the works of Albareda et al.12 on Gamma nails and Ozkan et al.13 on PFN nails (Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland) directly cover the use of distal blocking screws in these devices.

This prospective and randomized cohort study aimed to verify, based on the literature12,13 and the experience at our own Service, the indications for distal blocking in Gamma 3 nails as a treatment for AO 31-A1 and 31-A2 intertrochanteric femoral fractures, assessing the surgical time, irradiation of patients and healthcare staff, bleeding, collapse at the fracture focus and both medical complications and those derived from the fracture and/or osteosynthesis.13

Materials and methodsA total of 177 patients diagnosed with intertrochanteric femoral fractures (31-A1 or 31-A2 in the AO classification) were intervened at our Service through anterograde intramedullary nailing with a standard, Gamma 3 steel nail between June 2011 and January 2013. In all cases, the procedures were carried out through closed reduction and with drilling of the medullar canal up to 13mm in the femoral diaphysis and 15mm in the metaphyseal region. Patients were randomized, so that those born on an even-numbered year were intervened by osteosynthesis with a distally blocked nail, always dynamically, whilst those born on odd-numbered years were intervened using nails without distal blocking, thus forming two groups with 90 (50.8%) and 87 fractures (49.2%), respectively. We verified the homogeneity between both groups and observed statistically significant differences regarding the distribution by gender (P=0.030), Pfeiffer index (P=0.017) (both factors only in the group of 31-A1 fractures) and the type of fracture, so that patients intervened with blocked nails presented more complex lesions (P=0.044). Considering these results, we carried out an analysis of the available data stratified by type of fracture.

The criteria for exclusion from the study included: (1) fractures caused by high-energy trauma (falls and traffic accidents); (2) patients who were incorrectly randomized according to their date of birth; (3) unstable fractures requiring the use of a blocked nail or longer nails (particularly in AO 31-A2.3 and 31-A3 fractures); (4) pathological fractures; (5) implants from other commercial brands and (6) patients who did not wish to be included in the study, with no distinguishing features compared to the group which accepted to participate. These criteria led to the exclusion of 60 patients intervened for proximal femoral fractures during the same period of time.

The work comprised two phases: a transversal study in which the data of each patient was collected during hospital admission, and a longitudinal study in which the evolution of each patient was monitored during consultation. The first phase gathered intraoperative data on the dimensions of the implant, surgical time, radioscopy time, total (mGy) and absorbed (mGy m2) radiation doses, levels of hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (HTO) before the intervention and after 24h in order to calculate blood loss associated to the procedure, and requirements for transfusion of packed red blood cells (conducted by the Internal Medicine Service according to the usual protocol: Hb values under 8, symptomatic anemia and significant associated comorbidities). The study also gathered information on the cognitive and functional status of patients through the Pfeiffer scale and the Barthel index, respectively, the level of independence for walking (assessing the use of support devices) and the most significant medical complications, defined as those causing a significant vital risk, functional disability or problems related to the surgical wound.

We assessed all the radiographic data, including the level of reduction of the fracture compared to the contralateral hip in an anteroposterior radiograph (considering as correct reductions those with variations of the femoral cervicodiaphyseal angle under 5°, acceptable between 6° and 10° and poor above 11°), as well as the placement of the cephalic screw within the femoral head according to the Cleveland quadrants7,13,21,22 and depth within the subchondral bone.

All patients were allowed immediate load depending on their tolerance. Antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed for the first 24h after the intervention, along with antithrombotic prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparins for 30 days after discharge.

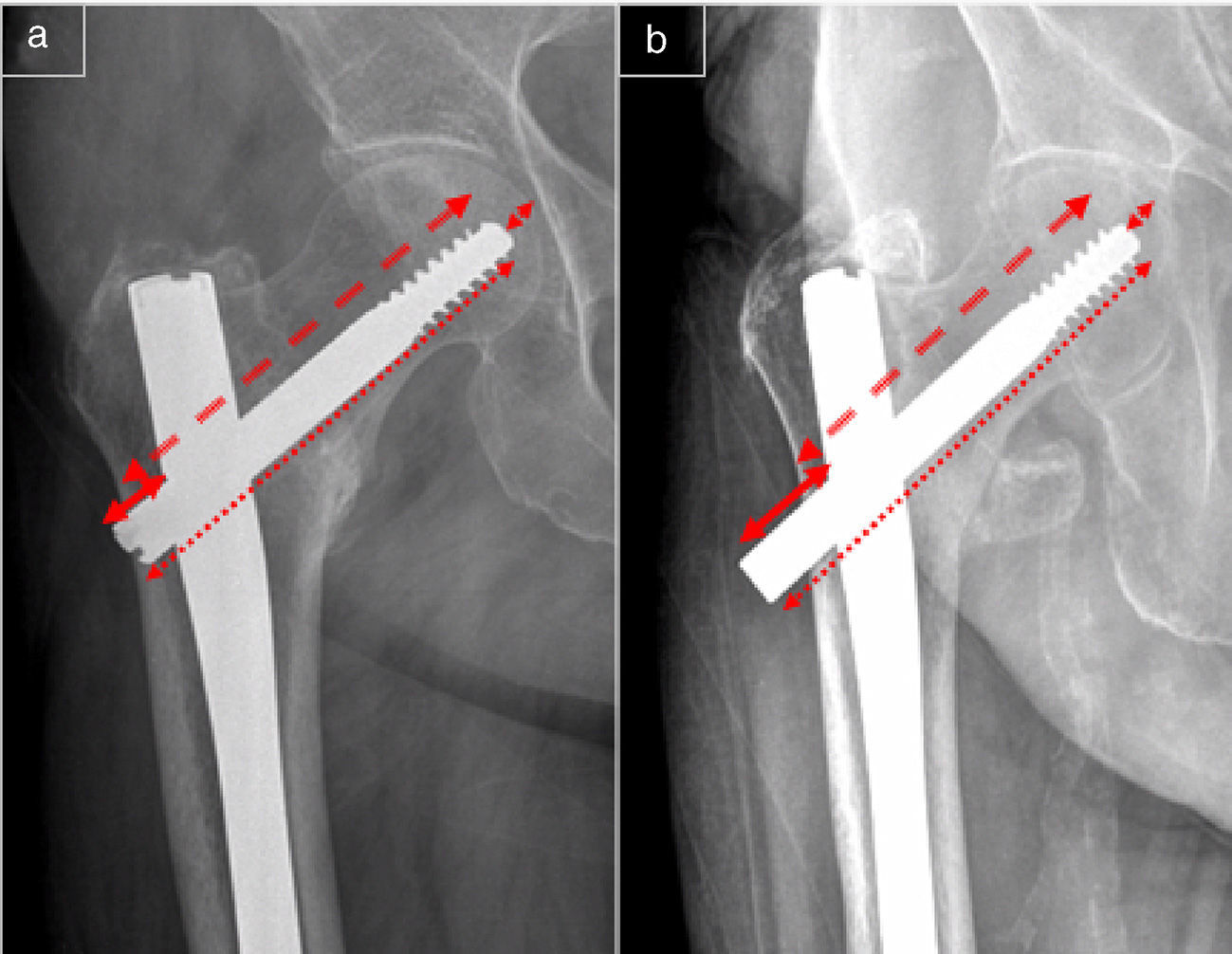

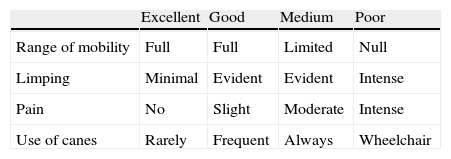

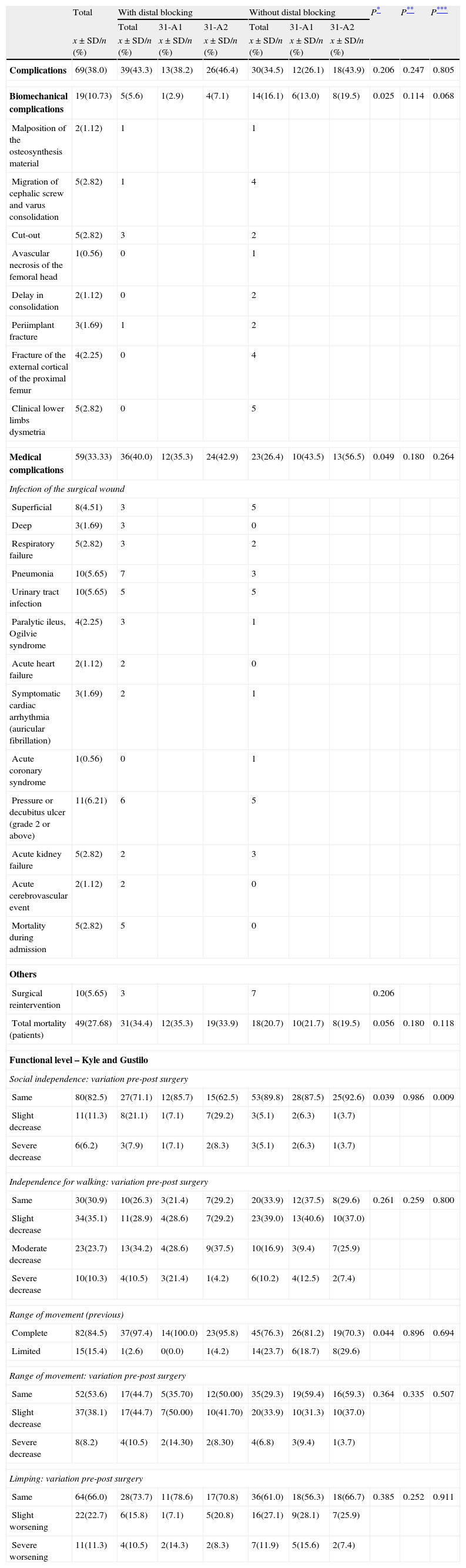

In the second phase of the study we carried out monitoring during consultation for at least 3 months after the intervention. We assessed clinical condition, functional level and quality of life using the Kyle and Gustilo index (Table 1) and the level of social independence measured as the possibility of living at home as opposed to the need to live with relatives or in a residence for the elderly and/or chronic patients. In addition, we also carried out radiographic controls in the anteroposterior and axial projections, in which the level of fracture collapse was measured as the distance between the nail and the distal tip of the cephalic screw (distance A) and as the distance from the external cortex of the femur to the tip of the cephalic screw (distance B) (Fig. 1), as well as variations in the position of the cephalic screw or the cervicodiaphyseal angle and biomechanical complications defined as those derived from the fracture and/or osteosynthesis. We considered as full consolidation the existence of a radiographic bone callus and the absence of symptoms at the fracture focus. All the radiographic assessments were carried out by the same surgeon using the software package IMPAX (v. 6.4, Agfa).

The anteroposterior radiograph of each evolution control showed the location of the cephalic screw in the subchondral bone (arrowheads) and the level of collapse of the fracture measured as the distance between the nail and the distal end of the cephalic screw (solid line) (distance A) and the distance from the external cortical of the femur to the tip of the cephalic screw (broken line) (distance B). These values depend on the focal distance of the X-ray tube, which varies in each case, so the real measurement of the cephalic screw (dotted line) was used as a constant, as this value was certain.

All this information was introduced into an MS Excel data matrix (Office, v. 2007. Microsoft) for its subsequent statistical analysis with the software package SPSS Statistics (v. 22.0, IBM), using the Student's t test for quantitative variables and the Chi-squared test for qualitative variables. We considered as statistically significant a value of P<0.05. We also applied a Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to the two groups being studied, with and without distal blocking, in relation to the probability of exitus and a Cox lineal regression to assess other possible variables associated to this outcome.

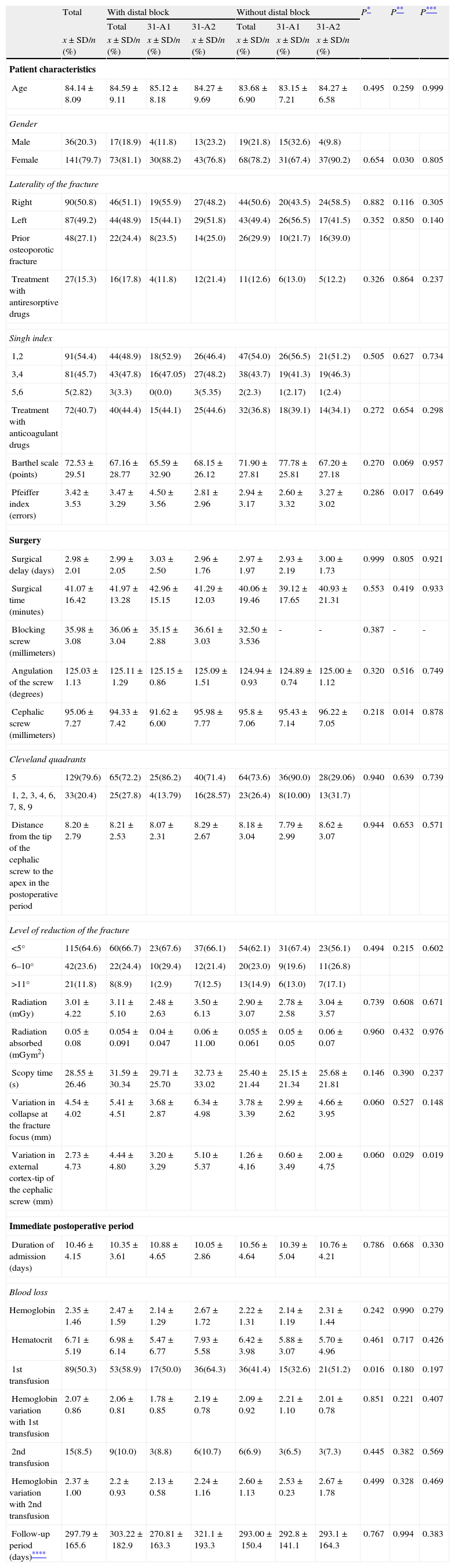

ResultsThe sample was comprised by 177 patients, 36 males (20.3%) and 141 females (79.7%) with a mean age of 84.14 years (range: 43–99 years). In total, 27.1% of patients had a previous history of osteoporotic fracture, 15.3% were following treatment with some type of antiresorptive and/or osteogenic drug and 40.7% with some anticoagulant or antiaggregant drug at the time of admission. The mean result in the Barthel scale was of 72.53 points and 3.42 errors in the Pfeiffer index. Regarding the fractures, 45.2% were classified as type 31-A1 and 54.8% as 31-A2 of the AO classification, with 90 of the intertrochanteric fractures occurring on the right side (50.8%) and 87 on the left (49.2%). The grade of osteoporosis determined by the trabecular architecture visible in simple anteroposterior radiographs of the hip (Singh method) was high in 54.4% of cases (Singh grades 1 and 2) and low in 45.7% of cases (Singh grades 3 and 4).

Out of the 177 patients who started the first phase of the study, 96 (53.9%) were monitored radiographically and clinically during traumatology consultation for at least 3 months after the surgical intervention, with a mean follow-up period of 297.79 days (range: 91–779 days). Losses during follow-up, including those of patients deceased in the first 90 days after surgery, accounted for 46.1% of cases.

In the cross-sectional phase of the study (n=177) (Table 2), the mean surgical delay was 2.98 days (range: 0–14 days) and the mean hospital stay was 10.46 days (range: 2–30 days). We achieved a good or acceptable reduction in 88.2% of the fractures and the cephalic screw was implanted in Cleveland quadrant 5 in 79.6% of cases and at a mean distance of 8.2mm from the joint surface (range: 3.1–19.3mm). No statistically significant differences were observed between the blocking groups.

Characteristics of the intervened patients, surgical procedure and postoperative evolution.

| Total | With distal block | Without distal block | P* | P** | P*** | |||||

| Total | 31-A1 | 31-A2 | Total | 31-A1 | 31-A2 | |||||

| x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | ||||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||||||

| Age | 84.14±8.09 | 84.59±9.11 | 85.12±8.18 | 84.27±9.69 | 83.68±6.90 | 83.15±7.21 | 84.27±6.58 | 0.495 | 0.259 | 0.999 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 36(20.3) | 17(18.9) | 4(11.8) | 13(23.2) | 19(21.8) | 15(32.6) | 4(9.8) | |||

| Female | 141(79.7) | 73(81.1) | 30(88.2) | 43(76.8) | 68(78.2) | 31(67.4) | 37(90.2) | 0.654 | 0.030 | 0.805 |

| Laterality of the fracture | ||||||||||

| Right | 90(50.8) | 46(51.1) | 19(55.9) | 27(48.2) | 44(50.6) | 20(43.5) | 24(58.5) | 0.882 | 0.116 | 0.305 |

| Left | 87(49.2) | 44(48.9) | 15(44.1) | 29(51.8) | 43(49.4) | 26(56.5) | 17(41.5) | 0.352 | 0.850 | 0.140 |

| Prior osteoporotic fracture | 48(27.1) | 22(24.4) | 8(23.5) | 14(25.0) | 26(29.9) | 10(21.7) | 16(39.0) | |||

| Treatment with antiresorptive drugs | 27(15.3) | 16(17.8) | 4(11.8) | 12(21.4) | 11(12.6) | 6(13.0) | 5(12.2) | 0.326 | 0.864 | 0.237 |

| Singh index | ||||||||||

| 1,2 | 91(54.4) | 44(48.9) | 18(52.9) | 26(46.4) | 47(54.0) | 26(56.5) | 21(51.2) | 0.505 | 0.627 | 0.734 |

| 3,4 | 81(45.7) | 43(47.8) | 16(47.05) | 27(48.2) | 38(43.7) | 19(41.3) | 19(46.3) | |||

| 5,6 | 5(2.82) | 3(3.3) | 0(0.0) | 3(5.35) | 2(2.3) | 1(2.17) | 1(2.4) | |||

| Treatment with anticoagulant drugs | 72(40.7) | 40(44.4) | 15(44.1) | 25(44.6) | 32(36.8) | 18(39.1) | 14(34.1) | 0.272 | 0.654 | 0.298 |

| Barthel scale (points) | 72.53±29.51 | 67.16±28.77 | 65.59±32.90 | 68.15±26.12 | 71.90±27.81 | 77.78±25.81 | 67.20±27.18 | 0.270 | 0.069 | 0.957 |

| Pfeiffer index (errors) | 3.42±3.53 | 3.47±3.29 | 4.50±3.56 | 2.81±2.96 | 2.94±3.17 | 2.60±3.32 | 3.27±3.02 | 0.286 | 0.017 | 0.649 |

| Surgery | ||||||||||

| Surgical delay (days) | 2.98±2.01 | 2.99±2.05 | 3.03±2.50 | 2.96±1.76 | 2.97±1.97 | 2.93±2.19 | 3.00±1.73 | 0.999 | 0.805 | 0.921 |

| Surgical time (minutes) | 41.07±16.42 | 41.97±13.28 | 42.96±15.15 | 41.29±12.03 | 40.06±19.46 | 39.12±17.65 | 40.93±21.31 | 0.553 | 0.419 | 0.933 |

| Blocking screw (millimeters) | 35.98±3.08 | 36.06±3.04 | 35.15±2.88 | 36.61±3.03 | 32.50±3.536 | - | - | 0.387 | - | - |

| Angulation of the screw (degrees) | 125.03±1.13 | 125.11±1.29 | 125.15±0.86 | 125.09±1.51 | 124.94±0.93 | 124.89±0.74 | 125.00±1.12 | 0.320 | 0.516 | 0.749 |

| Cephalic screw (millimeters) | 95.06±7.27 | 94.33±7.42 | 91.62±6.00 | 95.98±7.77 | 95.8±7.06 | 95.43±7.14 | 96.22±7.05 | 0.218 | 0.014 | 0.878 |

| Cleveland quadrants | ||||||||||

| 5 | 129(79.6) | 65(72.2) | 25(86.2) | 40(71.4) | 64(73.6) | 36(90.0) | 28(29.06) | 0.940 | 0.639 | 0.739 |

| 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 | 33(20.4) | 25(27.8) | 4(13.79) | 16(28.57) | 23(26.4) | 8(10.00) | 13(31.7) | |||

| Distance from the tip of the cephalic screw to the apex in the postoperative period | 8.20±2.79 | 8.21±2.53 | 8.07±2.31 | 8.29±2.67 | 8.18±3.04 | 7.79±2.99 | 8.62±3.07 | 0.944 | 0.653 | 0.571 |

| Level of reduction of the fracture | ||||||||||

| <5° | 115(64.6) | 60(66.7) | 23(67.6) | 37(66.1) | 54(62.1) | 31(67.4) | 23(56.1) | 0.494 | 0.215 | 0.602 |

| 6–10° | 42(23.6) | 22(24.4) | 10(29.4) | 12(21.4) | 20(23.0) | 9(19.6) | 11(26.8) | |||

| >11° | 21(11.8) | 8(8.9) | 1(2.9) | 7(12.5) | 13(14.9) | 6(13.0) | 7(17.1) | |||

| Radiation (mGy) | 3.01±4.22 | 3.11±5.10 | 2.48±2.63 | 3.50±6.13 | 2.90±3.07 | 2.78±2.58 | 3.04±3.57 | 0.739 | 0.608 | 0.671 |

| Radiation absorbed (mGym2) | 0.05±0.08 | 0.054±0.091 | 0.04±0.047 | 0.06±11.00 | 0.055±0.061 | 0.05±0.05 | 0.06±0.07 | 0.960 | 0.432 | 0.976 |

| Scopy time (s) | 28.55±26.46 | 31.59±30.34 | 29.71±25.70 | 32.73±33.02 | 25.40±21.44 | 25.15±21.34 | 25.68±21.81 | 0.146 | 0.390 | 0.237 |

| Variation in collapse at the fracture focus (mm) | 4.54±4.02 | 5.41±4.51 | 3.68±2.87 | 6.34±4.98 | 3.78±3.39 | 2.99±2.62 | 4.66±3.95 | 0.060 | 0.527 | 0.148 |

| Variation in external cortex-tip of the cephalic screw (mm) | 2.73±4.73 | 4.44±4.80 | 3.20±3.29 | 5.10±5.37 | 1.26±4.16 | 0.60±3.49 | 2.00±4.75 | 0.060 | 0.029 | 0.019 |

| Immediate postoperative period | ||||||||||

| Duration of admission (days) | 10.46±4.15 | 10.35±3.61 | 10.88±4.65 | 10.05±2.86 | 10.56±4.64 | 10.39±5.04 | 10.76±4.21 | 0.786 | 0.668 | 0.330 |

| Blood loss | ||||||||||

| Hemoglobin | 2.35±1.46 | 2.47±1.59 | 2.14±1.29 | 2.67±1.72 | 2.22±1.31 | 2.14±1.19 | 2.31±1.44 | 0.242 | 0.990 | 0.279 |

| Hematocrit | 6.71±5.19 | 6.98±6.14 | 5.47±6.77 | 7.93±5.58 | 6.42±3.98 | 5.88±3.07 | 5.70±4.96 | 0.461 | 0.717 | 0.426 |

| 1st transfusion | 89(50.3) | 53(58.9) | 17(50.0) | 36(64.3) | 36(41.4) | 15(32.6) | 21(51.2) | 0.016 | 0.180 | 0.197 |

| Hemoglobin variation with 1st transfusion | 2.07±0.86 | 2.06±0.81 | 1.78±0.85 | 2.19±0.78 | 2.09±0.92 | 2.21±1.10 | 2.01±0.78 | 0.851 | 0.221 | 0.407 |

| 2nd transfusion | 15(8.5) | 9(10.0) | 3(8.8) | 6(10.7) | 6(6.9) | 3(6.5) | 3(7.3) | 0.445 | 0.382 | 0.569 |

| Hemoglobin variation with 2nd transfusion | 2.37±1.00 | 2.2±0.93 | 2.13±0.58 | 2.24±1.16 | 2.60±1.13 | 2.53±0.23 | 2.67±1.78 | 0.499 | 0.328 | 0.469 |

| Follow-up period (days)**** | 297.79±165.6 | 303.22±182.9 | 270.81±163.3 | 321.1±193.3 | 293.00±150.4 | 292.8±141.1 | 293.1±164.3 | 0.767 | 0.994 | 0.383 |

The calculations were carried out based on the real data obtained for each variable.

The group of patients intervened through a blocked Gamma nail required a longer surgical time, more doses of radiation and a longer radioscopy time (41.97min, 3.11mGy and 31.59s, respectively) compared to the group treated with unblocked Gamma nails (40.06min, 2.90mGy and 25.40s), although these differences were not statistically significant. On the other hand, the dose of radiation absorbed was slightly higher in the group of patients with unblocked nails, compared to the group with blocked nails (0.055mGym2 and 0.054mGym2, respectively), albeit with no statistical significance.

Loss of blood associated to the fracture and the intervention was higher in the blocked group, with a mean decrease of 2.47 Hb points and 6.98 HTO points, compared to 2.22 and 6.42, respectively, in the unblocked group, with no statistically significant differences being found. In the first group, a total of 53 transfusions of packed red blood cells were conducted due to postoperative anemization, with a mean increase of 2.06 points in the Hb count, compared to 36 transfusions in the control group, with a mean increase of 2.09 points, with the differences being statistically significant for a number of transfusions (P=0.016). When stratifying these results according to the type of fracture, we observed that 17 patients with 31-A1 fracture and 36 with 31-A2 fracture treated with a blocked nail were transfused, a larger number than among the group intervened with a nail without distal blocking, where there were 15 cases in 31-A1 fractures and 21 in 31-A2 fractures. A trend toward statistical significance (P=0.180 for the 31-A1 group and P=0.197 for the 31-A2 group) was observed. We also found a statistical association with other variables, such as surgical delay, according to which those patients who were intervened later presented a greater decrease of their Hb (P=0.001) and HTO (P=0.001) values in the postoperative period, or the Hb and HTO values prior to surgery, so that patients with a higher grade of anemization were transfused more frequently (P=0.001) and these transfusions had a better performance regarding Hb (P=0.001) and HTO (P=0.015) points, or the complexity of the fracture, so that AO 31-A2 fractures presented a greater HTO decrease (P=0.018) and higher transfusion requirements (P=0.013) after the intervention.

In the longitudinal phase of the study (n=96) (Table 2) the collapse at the focus of the fracture measured as distance A and distance B (Fig. 1) was greater in the blocking group, with a mean value of 5.41mm and 4.44mm, respectively, compared to the group without blocking, where the values were 3.78mm and 1.26mm. Both measurements showed a trend toward statistical significance (P=0.06). The complexity of the fracture also affected the results, so that patients with AO 31-A2 fractures (with comminution of the posteromedial femoral cortical) suffered greater collapse at the focus of the fracture compared to 31-A1 fractures (distance A: 3.4 and 5.79mm, respectively). Upon stratification, we observed statistically significant differences regarding variation in the external cortical – tip distance of the cephalic screw (distance B) (P=0.029 in 31-A1 fractures and P=0.019 in 31-A2 fractures).

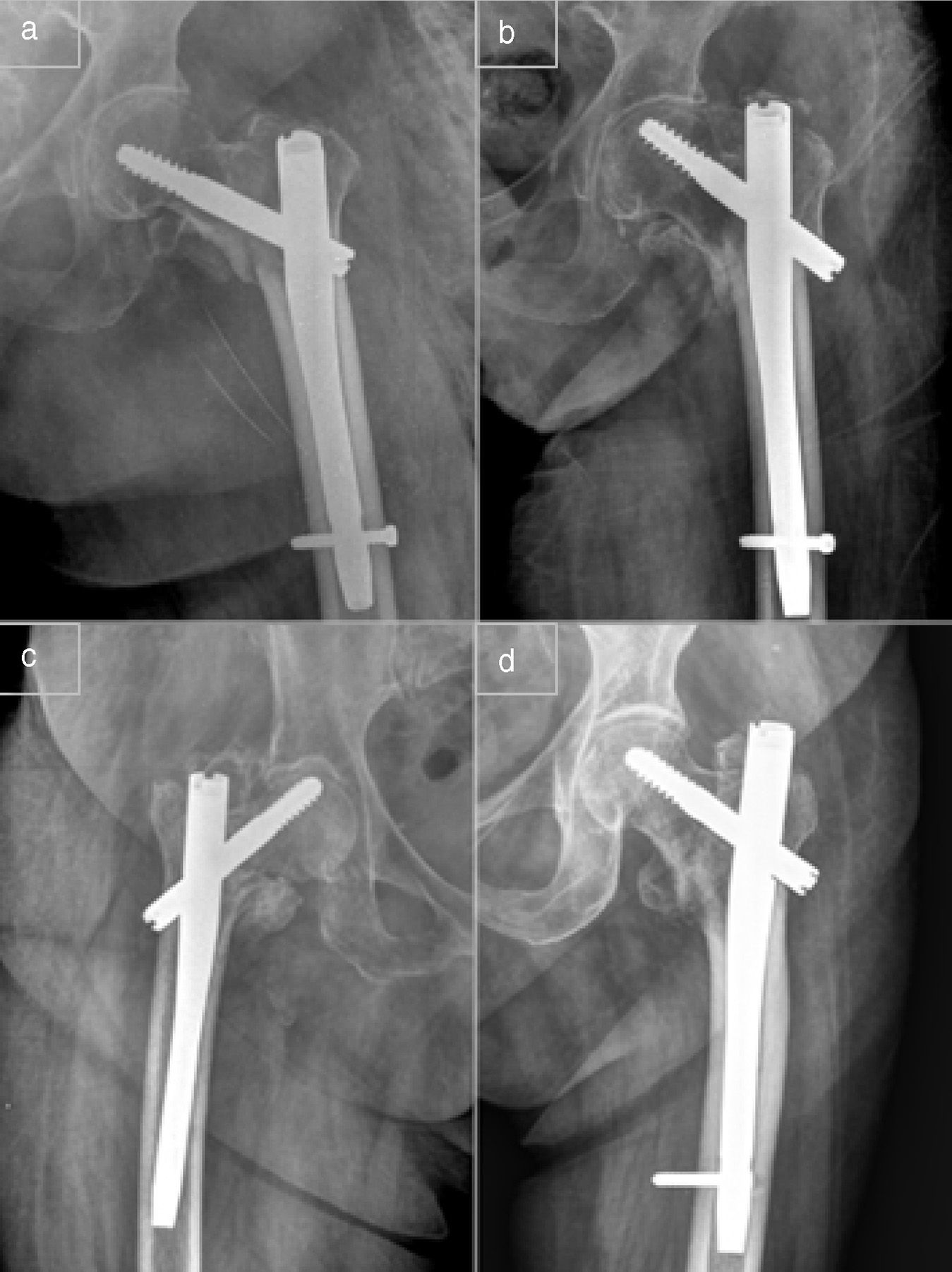

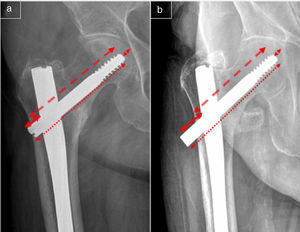

During follow-up we observed 27 mechanical complications in 19 patients (10.7%) (Table 3). Of these, 14 belonged to the group without blocking and five to the group with distal blocking, with these differences showing statistical significance (P=0.025), as well as a trend toward statistical significance when stratified by type of fracture (P=0.114 in 31-A1 fractures and P=0.068 in 31-A2 fractures). Among these complications were two symptomatic cases of delayed consolidation diagnosed through CT at 4 and 5 months, respectively, which evolved toward consolidation without requiring surgical treatment, 5 cases of migration of the cephalic screw and varus consolidation of the fracture (cervicodiaphyseal angle<110°) (Fig. 2a and b), 3 cases of posttraumatic periimplant fracture, 1 of which required a new osteosynthesis with a longer nail and with distal blocking, 4 cases of atraumatic fracture of the external cortical of the proximal femur, 1 case of avascular necrosis in a 90-year-old patient, and 5 cases of cut-out (Fig. 2c), 1 of which was lost during follow-up, another was an asymptomatic patient with low functional demands who did not wish to be treated and the remaining were intervened through implantation of an arthroplasty, partial in 2 cases and total in the other, all with cemented components. One unblocked nail in a fracture that developed cut-out effect was the only case of tear of the material, in this case through the orifice of the cephalic screw. Intraoperative biomechanical complications associated to the osteosynthesis represented 10.5% of the total, with 1 case of malposition of the distal block which required extraction after 2 months (Fig. 2d) and 1 case of intraarticular protrusion of the cephalic screw which required replacement by a shorter one, 4 days after the intervention.

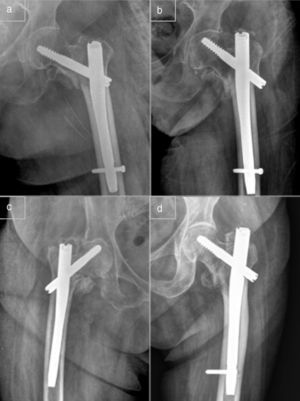

Biomechanical and medical complications. Clinical and functional condition of the patients.

| Total | With distal blocking | Without distal blocking | P* | P** | P*** | |||||

| Total | 31-A1 | 31-A2 | Total | 31-A1 | 31-A2 | |||||

| x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | x±SD/n (%) | ||||

| Complications | 69(38.0) | 39(43.3) | 13(38.2) | 26(46.4) | 30(34.5) | 12(26.1) | 18(43.9) | 0.206 | 0.247 | 0.805 |

| Biomechanical complications | 19(10.73) | 5(5.6) | 1(2.9) | 4(7.1) | 14(16.1) | 6(13.0) | 8(19.5) | 0.025 | 0.114 | 0.068 |

| Malposition of the osteosynthesis material | 2(1.12) | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Migration of cephalic screw and varus consolidation | 5(2.82) | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| Cut-out | 5(2.82) | 3 | 2 | |||||||

| Avascular necrosis of the femoral head | 1(0.56) | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Delay in consolidation | 2(1.12) | 0 | 2 | |||||||

| Periimplant fracture | 3(1.69) | 1 | 2 | |||||||

| Fracture of the external cortical of the proximal femur | 4(2.25) | 0 | 4 | |||||||

| Clinical lower limbs dysmetria | 5(2.82) | 0 | 5 | |||||||

| Medical complications | 59(33.33) | 36(40.0) | 12(35.3) | 24(42.9) | 23(26.4) | 10(43.5) | 13(56.5) | 0.049 | 0.180 | 0.264 |

| Infection of the surgical wound | ||||||||||

| Superficial | 8(4.51) | 3 | 5 | |||||||

| Deep | 3(1.69) | 3 | 0 | |||||||

| Respiratory failure | 5(2.82) | 3 | 2 | |||||||

| Pneumonia | 10(5.65) | 7 | 3 | |||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 10(5.65) | 5 | 5 | |||||||

| Paralytic ileus, Ogilvie syndrome | 4(2.25) | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| Acute heart failure | 2(1.12) | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia (auricular fibrillation) | 3(1.69) | 2 | 1 | |||||||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1(0.56) | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Pressure or decubitus ulcer (grade 2 or above) | 11(6.21) | 6 | 5 | |||||||

| Acute kidney failure | 5(2.82) | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Acute cerebrovascular event | 2(1.12) | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Mortality during admission | 5(2.82) | 5 | 0 | |||||||

| Others | ||||||||||

| Surgical reintervention | 10(5.65) | 3 | 7 | 0.206 | ||||||

| Total mortality (patients) | 49(27.68) | 31(34.4) | 12(35.3) | 19(33.9) | 18(20.7) | 10(21.7) | 8(19.5) | 0.056 | 0.180 | 0.118 |

| Functional level – Kyle and Gustilo | ||||||||||

| Social independence: variation pre-post surgery | ||||||||||

| Same | 80(82.5) | 27(71.1) | 12(85.7) | 15(62.5) | 53(89.8) | 28(87.5) | 25(92.6) | 0.039 | 0.986 | 0.009 |

| Slight decrease | 11(11.3) | 8(21.1) | 1(7.1) | 7(29.2) | 3(5.1) | 2(6.3) | 1(3.7) | |||

| Severe decrease | 6(6.2) | 3(7.9) | 1(7.1) | 2(8.3) | 3(5.1) | 2(6.3) | 1(3.7) | |||

| Independence for walking: variation pre-post surgery | ||||||||||

| Same | 30(30.9) | 10(26.3) | 3(21.4) | 7(29.2) | 20(33.9) | 12(37.5) | 8(29.6) | 0.261 | 0.259 | 0.800 |

| Slight decrease | 34(35.1) | 11(28.9) | 4(28.6) | 7(29.2) | 23(39.0) | 13(40.6) | 10(37.0) | |||

| Moderate decrease | 23(23.7) | 13(34.2) | 4(28.6) | 9(37.5) | 10(16.9) | 3(9.4) | 7(25.9) | |||

| Severe decrease | 10(10.3) | 4(10.5) | 3(21.4) | 1(4.2) | 6(10.2) | 4(12.5) | 2(7.4) | |||

| Range of movement (previous) | ||||||||||

| Complete | 82(84.5) | 37(97.4) | 14(100.0) | 23(95.8) | 45(76.3) | 26(81.2) | 19(70.3) | 0.044 | 0.896 | 0.694 |

| Limited | 15(15.4) | 1(2.6) | 0(0.0) | 1(4.2) | 14(23.7) | 6(18.7) | 8(29.6) | |||

| Range of movement: variation pre-post surgery | ||||||||||

| Same | 52(53.6) | 17(44.7) | 5(35.70) | 12(50.00) | 35(29.3) | 19(59.4) | 16(59.3) | 0.364 | 0.335 | 0.507 |

| Slight decrease | 37(38.1) | 17(44.7) | 7(50.00) | 10(41.70) | 20(33.9) | 10(31.3) | 10(37.0) | |||

| Severe decrease | 8(8.2) | 4(10.5) | 2(14.30) | 2(8.30) | 4(6.8) | 3(9.4) | 1(3.7) | |||

| Limping: variation pre-post surgery | ||||||||||

| Same | 64(66.0) | 28(73.7) | 11(78.6) | 17(70.8) | 36(61.0) | 18(56.3) | 18(66.7) | 0.385 | 0.252 | 0.911 |

| Slight worsening | 22(22.7) | 6(15.8) | 1(7.1) | 5(20.8) | 16(27.1) | 9(28.1) | 7(25.9) | |||

| Severe worsening | 11(11.3) | 4(10.5) | 2(14.3) | 2(8.3) | 7(11.9) | 5(15.6) | 2(7.4) | |||

The calculations were carried out based on the real data obtained for each variable.

A total of 59 patients (33.3%) (Table 3) suffered 73 major medical complications in the immediate postoperative period, 36 of them in the blocked group and 23 in the unblocked group, with these differences showing statistical significance (P=0.049) and a trend toward statistical significance upon stratification by fracture complexity (P=0.180 in 31-A1 fractures and P=0.264 in 31-A2 fractures). In total, 5 patients died during admission and 3 required surgical cleaning due to deep infection of the wound. All of these patients had been intervened with a distally blocked Gamma nail. In addition, we observed 8 superficial infections which were satisfactorily treated through antibiotic therapy guided by an antibiogram. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups.

A total of 11 patients (5.05%) were reintervened due to complications developed during surgery or follow-up, 7 in the group without distal blocking and 3 in the group with blocking, with no statistical significance (P=0.206). Among these patients were 3 cases of deep infection, 2 cases of malposition of the osteosynthesis material, 3 cases of cut-out and 1 periimplant fracture.

The rate of early mortality during the first month after surgery was 6.7% (12 patients) and the total mortality after 1 year of follow-up was 27.7% (49 patients), of which 63.26% (31 patients) were cases intervened with blocked nails. These differences showed a trend toward statistical significance (P=0.056) upon stratification according to the complexity of the fracture (P=0.180 in 31-A1 fractures and P=0.118 in 31-A2 fractures). The Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival showed that the incidence of exitus increased and took place earlier among the group with blocked Gamma nails. However, when other variables were included through a Cox lineal regression, it was possible to observe that, although blocking had a considerable effect on the rate of exitus, its statistical significance disappeared (P=0.132), and other variables, such as suffering medical complications and surgical wound infection, the Pfeiffer index and loss of blood during surgery, gained statistically significant relevance (P=0.049, P=0.043, P=0.030 and P=0.022, respectively).

Out of the 96 patients with a valid follow-up, those intervened with a distally blocked nail presented greater dependence on support devices in order to walk, greater loss of mobility with respect to their condition before the fracture, greater tip-effect pain (anterior aspect of the thigh) and greater social dependence, compared to the group without distal block, with only the latter showing statistical significance (P=0.039) (Table 3). Pain in the fascia lata was associated in a statistically significant degree to distally blocked nails, with 11 cases compared to 7 in the group without block (P=0.035).

DiscussionDistal blocking of intramedullary nails in the treatment of intertrochanteric femoral fractures has been used systematically in several studies.3,5–7,11,19,20 The onset of complications derived from its use, as well as the rotational stability provided by the nail-cephalic screw assembly,4 have led some authors to question its routine use and to establish indications for distal blocking. In fractures which fulfill instability criteria, especially those with subtrochanteric patterns, blocking is necessary to maintain the integrity of the fracture, enabling early consolidation and load,4,15,18 although in stable cases it can become a source of preventable complications.7,11–13 In their works on the use of intramedullary nails in proximal femoral fractures, and based on the biomechanical studies of Lacroix et al. and Rosemblum et al. Albareda et al.12 and Ozkan et al.13 established that distal blocking is not necessary for a satisfactory treatment of AO 31-A1 and 31-A2 fractures.

According to the findings of this study, the use of blocking screws with standard, Gamma 3 femoral nails entails a lower risk of biomechanical complications, a greater risk of postoperative medical complications and a higher rate of collapse of the fracture with respect to unblocked nails. The normal values of collapse reported by other studies vary between 2.7 and 4.8mm,5 coinciding with those found in the present work, where the mean value was of 4.54mm. The increase in blood loss and transfusion requirements and the higher incidence of exitus in this group could bear no clinical correlation due to the multiple variables involved, but the use of blocking should be one more variable to be taken into account.

The complications derived from the osteosynthesis and/or the fracture account for 10.7% of the sample, coinciding with other published data ranging between 3% and 16%.1,6,10,20 These were associated, with statistical significance, to the use of nails without distal blocking, and this relation was maintained independently of the complexity of the fracture. The incidence of cut-out in the literature and varies between 0% and 16%,1,6,10,15 with the most significant predictive parameters for its onset being the grade of reduction, fracture instability, tip-apex index or TAD under 25mm (Baumgaertner et al.17) and the placement of the cephalic screw in Cleveland quadrant 5.17,21–23 In our study there were 5 cases of cut-out (2.8%), all of them associated to technical errors, as in 3 cases the cephalic screw was placed in Cleveland quadrant 9 and the other 2 presented a tip-apex distance or TAD over 30mm with a cephalic screw which was too short.

In addition, there were 11 cases (6.1%) of surgical wound infection, more than in similar studies, which reported incidences between 0% and 3.6%.1,6,7,10 The incidence of surgical reintervention was 5.05%, coinciding with other literature references which reported values between 1.4% and 9.4%.6,18

In other case series, mortality at 1 year after the intervention ranged between 15% and 30% of patients intervened for intertrochanteric femoral fractures, whereas acute mortality (first month after the intervention) was around 9%,6,10,20 coinciding with the data recorded in the present study.

The results of this study, in addition to those found in other works,12,13 suggest that the use of distal blocking screws with Gamma 3 nails adds not only considerable stability to the osteosynthesis of intertrochanteric femoral fractures but can also be a source of complications. Therefore, their use should be restricted to cases in which the fracture requires additional stability to that provided by the nail itself, rather than cases which are stable after the reduction, like AO 31-A1 fractures, which in clinical practice represent around 25% of proximal femoral fractures.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Limitations of the studyIn this work, loss during follow-up accounted for 46.1% of the sample, due to the advanced age of patients (mean age of 84.18 years), added comorbidities and social problems, thus hindering attendance to periodic controls.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Vega M, Gil-Monzó ER, Rodrigo-Pérez JL, López-Valenciano J, Salanova-Paris RH, Peralta-Nieto J, et al. Randomized prospective study on the influence distal block and Gamma 3 nail on the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures of femur. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:26–35.