Fast-track surgery, or enhanced recovery, has appeared in the last 20 years or so as a combination of the optimisation of clinical protocols ans organisational processes, pursuing the reduction in surgical stress with the aim of reducing peri-operative comorbidities, convalescence time, and functional recovery, resulting in a reduction in admission time.

After a review of the European literature available on this subject, this article attempts to present an update. It highlights its interest and origins, basically being set out as a response to the question: ‘Why is this patient in Hospital today?’ It also attempts to summarise the essence of such programmes the search for immediate post-surgical mobilisation, being supported by a multidisciplinary approach. This includes a multimodal intervention and analgesia a limitation in the use of opiates, and the active participation by the patients in their own recovery.

Furthermore, mention is made of the initiatives by European State organisation as a boost to enhanced recovery programmes in their respective countries, as is the case in Denmark, France, and the United Kingdom.

The clinical outcomes published up to September 2015 have been reviewed. A subsequent decrease in mean hospital stay is observed in 11 studies, achieving patient satisfaction, low complication rates, a reduction in the transfusion rates, and with no apparent increase in re-admissions.

Mention is also made of the financial consequences, and how to implement these programmes.

As a conclusion, an analysis is made of the future challenges of fast-track surgery, such as the possibility of moving towards outpatient surgery or the obtaining of a surgery ‘with no risk or pain’ in general, for which there are still open lines of work.

La cirugía de recuperación rápida, o fast-track, aparece en las últimas décadas como una combinación de optimización de procesos organizativos y clínicos, persiguiendo la atenuación del estrés quirúrgico con el fin de reducir las comorbilidades perioperatorias y el tiempo de convalecencia y de recuperación funcional, resultando en una reducción del tiempo de hospitalización.

Tras la revisión de la literatura europea disponible sobre el tema, el artículo pretende realizar una actualización, poniendo de relieve su interés y orígenes, básicamente planteándose como una respuesta a la pregunta: «¿Por qué está el paciente en el hospital hoy?», e intentando resumir la esencia de este tipo de programas: buscar la movilización posquirúrgica inmediata apoyándose en un enfoque multidisciplinar, una intervención y analgesia multimodales, una limitación en el uso de opiáceos y una participación activa del paciente en su propia recuperación.

Asimismo, se mencionan las iniciativas de organismos estatales europeos como fomento a programas de recuperación rápida en sus respectivos países, como es el caso en Dinamarca, Francia y el Reino Unido.

Se han revisado los resultados clínicos publicados hasta el mes de septiembre de 2015, observando en 11 estudios una reducción consecuente de la estancia media, consiguiendo la satisfacción de los pacientes, unas tasas de complicaciones bajas y una reducción de la tasa de transfusiones, sin que aparezca un aumento de los reingresos.

Se mencionan también las consecuencias económicas y la forma de implementar tales proyectos.

Como conclusión, se analizan los retos futuros de la cirugía fast-track, como puede ser el posible planteamiento hacia una cirugía ambulatoria, o de forma más general la obtención de una cirugía «sin dolor ni riesgo», existiendo para ello todavía líneas de trabajo abiertas.

Fast-track surgery or simplified peri-operative process may be defined as all surgery that seeks to reduce surgical stress by fast-paced rehabilitation, leading to early hospital discharge and an improvement in the patient's hospital experience.

According to professor Henrik Kehlet, leading peri-operative therapy in the Hospital Universitario Rigshospitalet of Copenhagen (Denmark), and a pioneer of fast-track surgery, this is a “a package of care management that aims to reduce morbidity to deliver a pain and risk free procedure that significantly reduces the number of days a patient is in the hospital”.1

Fast-track programmes have their origin in colorectal surgery but have been applied to a multitude of surgical specialities since the end of the 1990s. Professor Kehlet's influence contributed to their adoption in orthopaedic surgery, mainly in knee and hip arthroplasty. For Dr. Peter Pilot, senior ex-researcher of the Orthopaedic Department of the Hospital Reinier de Graaf in Delft (Holland), the rapid recovery programme is “more a philosophy than an actual rigid programme. It is a continued willingness to improve care around the orthopaedic patient”.2

The clinical need for rapid recovery programmesMajor surgery is usually followed by pain, fatigue, nausea, stress-induced organ dysfunction, catabolism, changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis, etc., which may all lead to a risk in medical complications (cardiopulmonary, thromboembolic, cognitive, infections, etc.) and also functional deterioration leads to hospital stay and subsequent rehabilitation.3

Based on the question “Why is the patient in hospital today?”3,4 and analysing the many factors involved in peri-operative care, the concept of fast-track surgery, ERAS (enhanced recovery after surgery), enhanced recovery or rapid recovery has evolved based on a multimodal intervention in all peri-operative care, aimed at reducing postoperative organ dysfunction and its associated morbidity.

OriginsPatient healthcare has notably improved during the last 2 decades. Historically the patients were hospitalised for weeks after arthroplasty, with a long bed-rest time but today hospital stay has been reduced to under one week.

In the 1980s and 1990s the creation of so-called clinical pathways began. This was initially restricted to English-speaking countries,5 as a management tool for facilitating systematic and multidisciplinary care to the patient.

Clinical pathways focus on the quality and efficiency of patient care and are evidence-based.6 They are systematically developed to help both the professional and the patient. They are multidisciplinary and are designed to order the clinical management of the procedure, from the moment decisions are taken to hospital admission. They aim to minimise delays and consumption of resources, maximising care quality. They represent state of the art medical care. 7 Their application, together with a quality healthcare programme8 has led to working in accordance with the concept and methodology of continuous improvement.

In the mid-nineties, professor Henrik Kehlet and his work team synthesised, integrated and applied the findings from a research which focused on reducing the physiological and psychological stress associated with surgical interventions, thus reducing a series of possible complications.3 An extensive programme was started, now commonly known as fast-track surgery, driving the clinical pathway to a higher level.9

Fast-track surgery evolved as a combined co-ordinated effort of modern educational concepts to the patient with the new methods of anaesthesia and analgesia. Their intention is to reduce the response to stress and minimise pain and malaise. One has to take into account that the key pathogenic factor in post-operative morbidity, excluding surgical and anaesthetic techniques, is response to surgical stress which leads to increased demands on organ function.3

The concept has been tested with great success on different surgical specialities, and has resulted in rapid recovery, an improved analgesia, reduced organ dysfunction and lower morbidity. Although most documentation on surgical physiopathology and parameters of clinical results derive from abdominal procedures, significant improvements have been made during the last few years in major joint replacement.

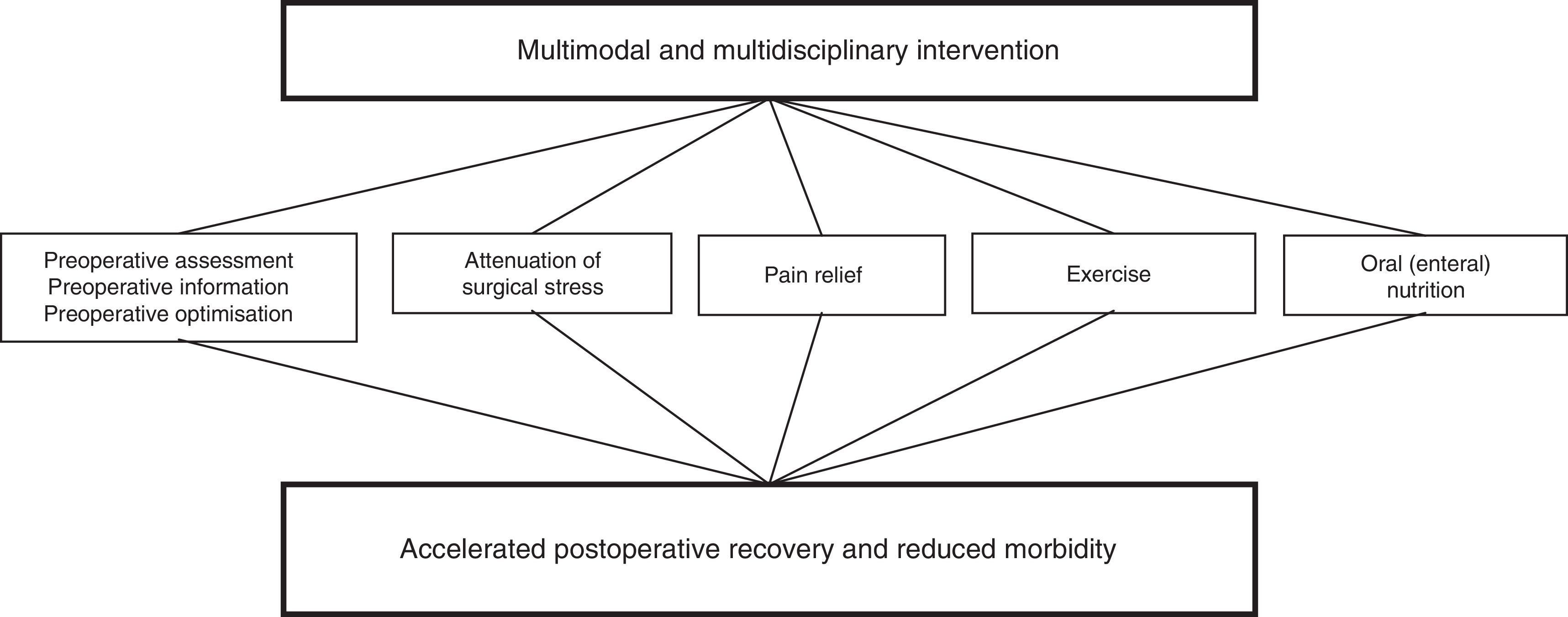

The keystone of rapid recovery programmesThe change in focus of rapid recovery programmes in relation to conventional clinical pathways is multimodal intervention implementation (Fig. 1). Multimodal interventions may lead to a major reduction in the undesirable sequelae from surgery and fast recovery which as a result will lead to a reduction in postoperative morbidity and overall procedural costs.9

Multimodal model of early rehabilitation.

Source: Kehlet and Dahl.11

The success of the fast-track programme resides in patients moving around quickly after surgery, within 24 hours, and requires a multidisciplinary focus: participation from anaesthetists, surgeons, nurses and physiotherapists. The anaesthetist is key to having a wider perspective of the entire painful process of the patient. Clinical anaesthetic practice today emphasizes preoperative optimisation, intraoperative monitoring optimisation, exhaustive control of fluid therapy,10 maintaining normothermia, restrictive transfusion policies and the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting.11

According to the multimodal analgesia concept, the combination of different types of analgesics with different administration routes is higher to the action of a single analgesic or single technique and pain relief is therefore higher, with fewer side effects from the administered drugs.12 The multimodal analgesia technique4,12 focuses on the nociceptive blockage, and inflammatory response. Furthermore, pain relief must come about both in repose and during movement (pain evoked by movement) so that the patient may participate in an intensive rehabilitation programme, leading to reduced morbidity.

Available analgesic modalities for postoperative pain management include regional or local techniques such as neuraxial analgesia and peripheral nerve blocks, as well as infiltration into the site and intra-articular or intra-cavity administration of local anaesthetics.13 Analgesia with opiates should preferably be administered in minimum quantities to prevent adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, sedation, dizziness, somnolence, kidney dysfunction and constipation, all of which lead to a delay in recovery.14

Orthopaedic surgical innovations such as less invasive approach pathways, may have a positive effect on optimising healthcare quality and a higher reduction in hospital stay,15 although it has been demonstrated that another essential factor for rapid recovery is the patients’ pre-operative education.16 Ideally, preoperative education includes rehabilitation exercises which will be made in the postoperative period. The patient's education and motivation reduces their anxiety, provides greater autonomy, allows them to be more personally active in their own recovery and has a positive influence on pain management.17

Lastly, fast-track surgery implies review of the essential principles of pre-intra- and-post-operative care, on occasions opposing the traditions to the evidence-based medicine. A periodical assessment of routine practices is essential in accordance with existing evidence. Although there is no reference guide, the main recommendations18 based on systematic review include non systematic use of probes, drains, catheters, passive continuous movement devices, no restrictions on mobility in the case of hip arthroplasty, or the withdrawal from surgical closure in extension in the case of knee arthroplasty. Placing limits on fasting and ischaemia time is also recommended.

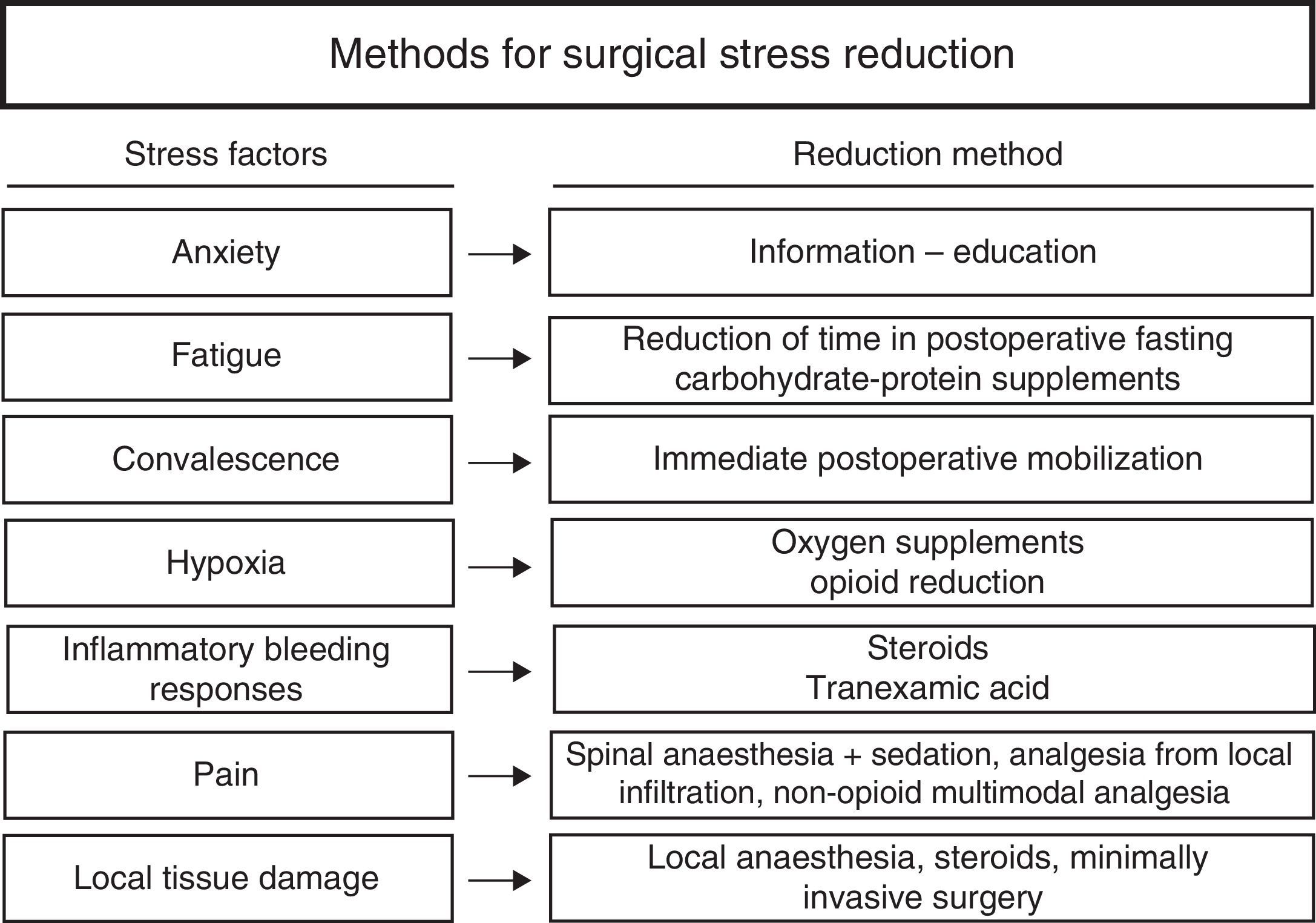

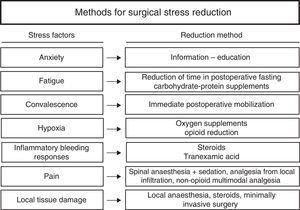

To conclude, a multimodal treatment is essential in rapid recovery. The use of an appropriate clinical pathway and optimisation of the procedures, combined with care focused on a reduction in surgical stress both in the patient's body and mind (Fig. 2), combined with an active involvement of the patient in their own recovery, notably boosts rehabilitation, satisfaction and safety.6

Measures for reducing surgical stress.

Source: Kehlet and Wilmore.9

In Denmark, fast-track surgery was successfully adopted by the orthopaedic surgery departments,19 promoted by the Danish Orthopaedic Society [DOS] and the Unit of Peri-operative Nursing Care founded by the Danish Ministry of Health. According to the data reported to the national patients register (Landspatientregistret), median average hospital stay dropped from 10 days in primary hip arthroplasty and 11 days in primary knee arthroplasty in 2000 to 4 days in 2009. Mean stay dropped from 10.9 days in hip arthropoasty in 2000 to 5.0 days in 2009, and in knee arthroplasty from 12.6 days to 5. 1 day.

Recently, a great many European countries have begun to promote this type of care. In France, for example, the Regional Health Agency of Ródano-Alpes (Agence Régionale de Santé Rhône-Alpes [ARS]) promotes the development of improved rehabilitation after surgery (réhabilitation améliorée après chirurgie [RAC]) through initiatives made together with the GRACE group (Groupe francophone de Réhabilitation Améliorée après Chirurgie), founded at the beginning of 2014.20

In the UK, the National Health System, NHS England, is looking for ways to comply with the recent Stevens Challenge of the NHS five year forward view plan which demands improvement in productivity to the tone of 22 billion pounds for 2020/21. The Getting it right first time (GIRFT) report, by professor Briggs,21 published at the end of 2012 and considered to reflect the current state of orthopaedic surgery in England, stipulated that within the necessary changes to improve productivity of healthcare in orthopaedic surgery it is essential to work in conjunction with primary healthcare, to redesign the clinical pathways, good practice guidelines and updated protocols, the establishment of specialised benchmark hospitals, and a greater involvement of the patient. Specifically, they recommended the adoption of enhanced recovery programmes and their extension to further orthopaedic procedures in order to improve clinical findings and reduce hospital stays. The secretary for State and the NHS England financed a national pilot project aimed at developing the study strategies.

Clinical results publishedRapid recovery surgery refers to work carried out on an organisational and clinical level, achieving a reduction in convalescence time. However no unified criteria exist to measure the partial or total obtainment of objectives, nor have minimum results reached been considered to establish the so-called “rapid recovery”.

In preparation of this article, we conducted a review of the literature until September 2015 with the search terms: fast track, rapid recovery, enhanced recovery or accelerated rehabilitation and arthroplasty. Only European articles which presented clinical findings were included in order to observe the European philosophy of fast-track surgery, apparently with greater similarities in their health systems.22 Rapid recovery programmes were also actually being applied in other continents.

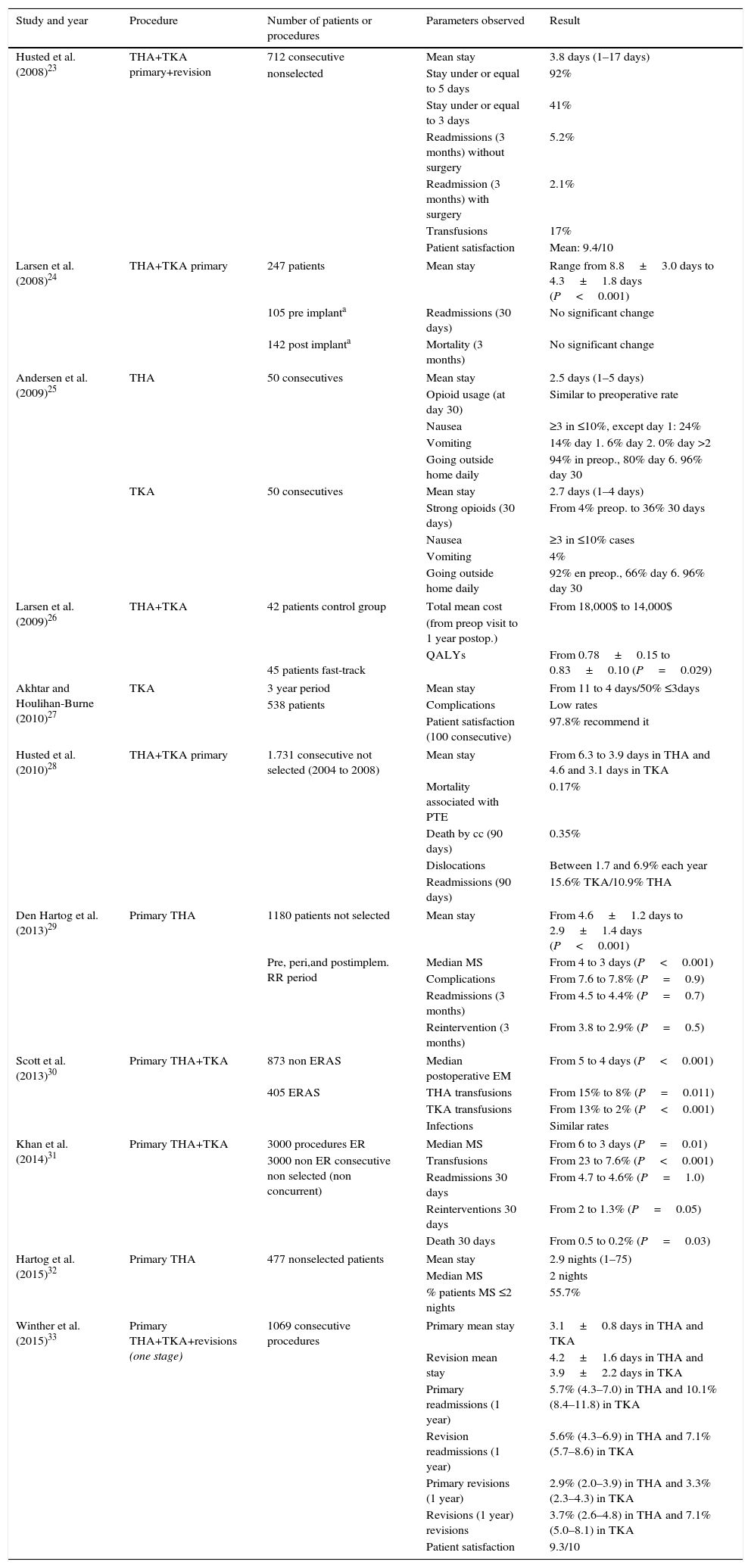

Table 1 extracts and lists the main parameters of recovery and safety observed in the 11 selected articles.

Revision of results from the literature in the main parameters of recovery and safety of the rapid recovery programmes.

| Study and year | Procedure | Number of patients or procedures | Parameters observed | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husted et al. (2008)23 | THA+TKA primary+revision | 712 consecutive | Mean stay | 3.8 days (1–17 days) |

| nonselected | Stay under or equal to 5 days | 92% | ||

| Stay under or equal to 3 days | 41% | |||

| Readmissions (3 months) without surgery | 5.2% | |||

| Readmission (3 months) with surgery | 2.1% | |||

| Transfusions | 17% | |||

| Patient satisfaction | Mean: 9.4/10 | |||

| Larsen et al. (2008)24 | THA+TKA primary | 247 patients | Mean stay | Range from 8.8±3.0 days to 4.3±1.8 days (P<0.001) |

| 105 pre implanta | Readmissions (30 days) | No significant change | ||

| 142 post implanta | Mortality (3 months) | No significant change | ||

| Andersen et al. (2009)25 | THA | 50 consecutives | Mean stay | 2.5 days (1–5 days) |

| Opioid usage (at day 30) | Similar to preoperative rate | |||

| Nausea | ≥3 in ≤10%, except day 1: 24% | |||

| Vomiting | 14% day 1. 6% day 2. 0% day >2 | |||

| Going outside home daily | 94% in preop., 80% day 6. 96% day 30 | |||

| TKA | 50 consecutives | Mean stay | 2.7 days (1–4 days) | |

| Strong opioids (30 days) | From 4% preop. to 36% 30 days | |||

| Nausea | ≥3 in ≤10% cases | |||

| Vomiting | 4% | |||

| Going outside home daily | 92% en preop., 66% day 6. 96% day 30 | |||

| Larsen et al. (2009)26 | THA+TKA | 42 patients control group | Total mean cost | From 18,000$ to 14,000$ |

| 45 patients fast-track | (from preop visit to 1 year postop.) | |||

| QALYs | From 0.78±0.15 to 0.83±0.10 (P=0.029) | |||

| Akhtar and Houlihan-Burne (2010)27 | TKA | 3 year period | Mean stay | From 11 to 4 days/50% ≤3days |

| 538 patients | Complications | Low rates | ||

| Patient satisfaction (100 consecutive) | 97.8% recommend it | |||

| Husted et al. (2010)28 | THA+TKA primary | 1.731 consecutive not selected (2004 to 2008) | Mean stay | From 6.3 to 3.9 days in THA and 4.6 and 3.1 days in TKA |

| Mortality associated with PTE | 0.17% | |||

| Death by cc (90 days) | 0.35% | |||

| Dislocations | Between 1.7 and 6.9% each year | |||

| Readmissions (90 days) | 15.6% TKA/10.9% THA | |||

| Den Hartog et al. (2013)29 | Primary THA | 1180 patients not selected | Mean stay | From 4.6±1.2 days to 2.9±1.4 days (P<0.001) |

| Pre, peri,and postimplem. RR period | Median MS | From 4 to 3 days (P<0.001) | ||

| Complications | From 7.6 to 7.8% (P=0.9) | |||

| Readmissions (3 months) | From 4.5 to 4.4% (P=0.7) | |||

| Reintervention (3 months) | From 3.8 to 2.9% (P=0.5) | |||

| Scott et al. (2013)30 | Primary THA+TKA | 873 non ERAS | Median postoperative EM | From 5 to 4 days (P<0.001) |

| 405 ERAS | THA transfusions | From 15% to 8% (P=0.011) | ||

| TKA transfusions | From 13% to 2% (P<0.001) | |||

| Infections | Similar rates | |||

| Khan et al. (2014)31 | Primary THA+TKA | 3000 procedures ER | Median MS | From 6 to 3 days (P=0.01) |

| 3000 non ER consecutive non selected (non concurrent) | Transfusions | From 23 to 7.6% (P<0.001) | ||

| Readmissions 30 days | From 4.7 to 4.6% (P=1.0) | |||

| Reinterventions 30 days | From 2 to 1.3% (P=0.05) | |||

| Death 30 days | From 0.5 to 0.2% (P=0.03) | |||

| Hartog et al. (2015)32 | Primary THA | 477 nonselected patients | Mean stay | 2.9 nights (1–75) |

| Median MS | 2 nights | |||

| % patients MS ≤2 nights | 55.7% | |||

| Winther et al. (2015)33 | Primary THA+TKA+revisions (one stage) | 1069 consecutive procedures | Primary mean stay | 3.1±0.8 days in THA and TKA |

| Revision mean stay | 4.2±1.6 days in THA and 3.9±2.2 days in TKA | |||

| Primary readmissions (1 year) | 5.7% (4.3–7.0) in THA and 10.1% (8.4–11.8) in TKA | |||

| Revision readmissions (1 year) | 5.6% (4.3–6.9) in THA and 7.1% (5.7–8.6) in TKA | |||

| Primary revisions (1 year) | 2.9% (2.0–3.9) in THA and 3.3% (2.3–4.3) in TKA | |||

| Revisions (1 year) revisions | 3.7% (2.6–4.8) in THA and 7.1% (5.0–8.1) in TKA | |||

| Patient satisfaction | 9.3/10 | |||

THA: total hip arthroplasty; TKA: total knee arthroplasty; cc: complications; MS: mean stay; ER: enhanced recovery; ERAS: enhanced recovery after surgery; QALYs: quality-adjusted life-years; RR: rapid recovery; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

Although there are no minimum criteria or results to measure definitive obtainment of a rapid recovery, review of the literature underlines consequential and statistically significant reduction in mean stay, compared with previous stay which was between 2.525 and 4.3 days24 according to studies and depending on the point of departure, differences in patient satisfaction23,27,33 (9.3 and 9.4/10 and 97.8% of recommendations), low complication rates27,28,31 or similar24,29 to the period prior to implementation, a reduction in transfusion rates30,31 (from 15% to 8% in hip replacements and from 13% to 2% in knee replacements, or from 23% to 7.6% in primary knee and hip), with no appearance of an increase in readmissions.24,28,29,31,33 There was also an agreement regarding the nonselection of patients, with high risk patients also being able to benefit from this type of care.

In addition, publications of the most recent cases of Dr. Henrik Husted from the Hospital Hvidovre in Denmark refer to a mean stay in THP and TKP of 1.5 days in 2010,2 whilst in 201134 a stay of between 1 and 2 days could be achieved, with a peri-operative analgesia improvement (multimodal and avoiding the use of opioids), a reduction in orthostatic hypotension risk, an improvement in the function of the quadriceps and management of internal logistic problems which could impede high temperature.

Is rapid recovery for financial reasons?Reductions in hospital stays, complications and the use of consumables, together with changes in analgesia and nursing and physiotherapy care has a major impact on the cost of these procedures.

In 2009, the Larsen et al.26 study reported a 22% reduction in the cost of arthroplasty per patient, associated with an increase in quality of life related to health, whilst Husted et al. published that same year a saving of 24% per patient operated on for a total knee replacement,35 as surgery, reanimation, hospital ward, analgesic treatment and physiotherapy costs all fell.

Using data from 2013 regarding mean cost of all patient diagnosis-related groups (AP-DGR's 209 —major joint replacement except hip and inferior member replacement, except due to complications—, and 818—hip replacement except due to complications—of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality website,36 it was possible to calculate the hypothetical cost reduction to be obtained for primary knee and hip arthroplasties when rapid recovery programmes were applied in Spain. A 20% reduction per patient would mean a reduction of €1700 per knee replacement, the cost of the AP-DRG 209 would drop from €8500 to 6800, and €1840 in hip, with the cost of AP-DRG 818 dropping from €9200 to €7360. A major part the saving in costs would be reflected as cost of opportunity for the hospitals.

Despite the need for health system actions and projects to focus on efficacy and sustainability, fast-track surgery did not arise out of the search for economy. In all the studies under review the main objective was healthcare quality and continuous improvement, with economic impact being a consequence of doing what was right for the patient.

The implementation processAlthough in the literature it is not specifically detailed, the process of implementation of a rapid recovery programme involves an organisational change mostly based on personnel. It maybe carried out sequentially, or gradually, without creating any disturbance to the centre,17 but their main challenge resides in the management of resistance to change, inherent in any organisation.37

Success consists in creating a cohesive multidisciplinary team, with a single message and a common objective: the search for continuous evidence-based improvement. The professionals in direct contact with the patients are those who can and should cause the optimisation of the processes, the updating of clinical procedures and patient education. However, the workload, the centre size, and traditions and habits are some of the standard obstacles which considerably impede or delay the execution of these programmes. For this, the choice of a project coordinator outside the organisation or the multidisciplinary team may be a point to consider.

As previously seen, as there are no measurement criteria regarding the obtainment of optimum recovery, and as there are continuously innovations and new evidence, it is essential that the multidisciplinary team regards the project as a new way of working, a continuous improvement, instead of a project with a beginning and an end. As a result, and regardless of the point of departure, any organisation may adopt its own recovery programme and periodically plan a redesign of its structural processes, and indeed its clinical protocols.

Future goalsThe reduction in post-surgical recovery time and the consequent reduction in hospital stay opens up the debate regarding the possibility, and safety of carrying out outpatient arthroplasty surgery. Procedures without hospital admittance have already been described in North American publications,38–42 and recently they have also been reported in Europe. Although there is a limited casuistic – 24 and 20 patients respectively – both European studies of Den Hartog et al.43 and Kort et al.44 from 2015 conclude that outpatient surgery is possible and satisfactory for unicompartmental hip and knee replacements in selected patients with a natural evolution within the rapid recovery programmes, although the latter do not imply any patient selection.

Over and above the need for hospital stay and although rapid recovery surgery has been able to considerably decrease convalescence time and hospital stay time as well as morbidities, challenges still remain in order to achieve hypothetical “painless, risk-free” surgery.4 Perioperative risk needs to be mainly worked upon, with re-assessment of the specific risk by patients or types of patients, aimed at reducing the postoperative risk of the patients with high preoperative risks.45 Efforts to improve pain management may be focused towards the study of new analgesics, avoiding the use of opiates, and towards the search for methods to impede transition of postoperative severe pain to chronic pain.46 The future development of rapid recovery surgery will also lead to the analysis of the techniques which enable change to be made to inflammatory responses, knowing the precise need for postoperative rehabilitation and reconsidering international directives regarding thromboembolic prophylaxisis treatment.47

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence v.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for this research no experiments on human beings or animals have been conducted.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests relating to the subject matter of this document.

Please cite this article as: Molko S, Combalia A. La cirugía de recuperación rápida en las artroplastias de rodilla y cadera. Una actualización. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:130–138.