To evaluate, from a clinical perspective, and with easily identifiable variables, those factors that influence the survival of patients admitted to a care unit designed for the comprehensive treatment of patients with hip fracture after being surgically treated.

Material and methodsA prospective study was conducted on a cohort of patients (n=202) aged 65 years or older with a low impact hip fracture, who were surgically intervened in a tertiary hospital. An analysis was performed to determine mortality at 90 days, and at one and 2years after surgery using demographic, clinical, analytical, and functional variables.

ResultsThe independent risk factors of mortality in the 3periods analyzed were age (P=.047, P=.016, and P=.000 at 90 days, 1, and 2 years, respectively) and a low Barthel index (P=.014, P=.005, and P=.004 at 90 days, 1, and 2 years, respectively). Male sex (P=.004) and a high risk for anaesthesia (P=.011) were only independent risk factors of mortality at 2years after surgery.

Discussion and conclusionAge and dependency were the major determining factors of mortality at 30 days, 1, and 2 years after surgery for hip fracture. Both are easily measurable to identify patients susceptible to poor outcomes, and could benefit from a more thorough care plan.

Valorar desde una perspectiva clínica y con variables fácilmente identificables aquellos factores que influyen en la supervivencia de los pacientes ingresados en una unidad asistencial diseñada para el tratamiento integral de pacientes con fractura de cadera, tras ser intervenidos quirúrgicamente.

Material y métodoEstudio prospectivo de una cohorte de pacientes (n=202) de edad igual o mayor de 65 años con fractura de cadera de bajo impacto, intervenidos quirúrgicamente en un hospital terciario, que analizó la mortalidad a 90 días, 1 y 2años tras la intervención con relación a variables demográficas, clínicas, analíticas y de funcionalidad.

ResultadosLos factores de riesgo independientes de mortalidad en los 3periodos analizados fueron la edad (p=0,047; 0,016 y 0,000 a 90 días, 1 y 2 años, respectivamente) y el bajo índice de Barthel (p=0,014; 0,005 y 0,004 a 90 días, 1 y 2 años respectivamente). Sin embargo, el sexo masculino (p=004) y el riesgo para anestesia (p=0,011) resultaron ser solo factores de riesgo independientes de mortalidad a los 2años de la intervención quirúrgica.

Discusión y conclusiónTanto a corto plazo (30 días) como hasta los 2 años de la intervención quirúrgica por fractura de cadera los mayores condicionantes de mortalidad fueron la edad y la dependencia. Ambos son parámetros fácilmente medibles que permiten identificar a pacientes susceptibles de mala evolución desde el ingreso y que podrían beneficiarse de una atención más exhaustiva.

Hip fractures affect the proximal third of the femur, between the head and 5cm below the trochanter minor.1 Low impact fractures reduce life expectancy and may be considered as a risk factor for short- and long-term mortality.2 Most of the persons affected are over 65 years of age and 75% are female, often with chronic diseases, at risk for functional decline3 and mortality due to both the fracture and its complications as well as their own fragility.4 The risk factors described for mortality within the term of one month following an osteoporotic hip fracture include, among others, advanced age, male gender, prior comorbidity or cognitive impairment5,6 and, in the longer term (from 1 to 3 years after), the other factors added include high-risk indications as defined by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA), dependency, scant functional capacity or malnutrition.7–9 The personal characteristics of patients are, in and of themselves, risk factors for mortality that require comprehensive multidisciplinary care for peri-operative preparation and maintenance, and also for the prevention and handling of complications. This care model has been shown to reduce mortality one month10,11 and one year8,11 after the surgical procedure.

The aetiopathogenesis of hip fractures involves osteoporosis and falls.12 In view of the ageing of the population, the number of cases will increase in the decades ahead, although some age-adjusted rates show stagnation or reduction.13 In Spain, an estimate produced in 2013 considered the risk of hip fracture after 80 years of age to range from 6 to 32% in women and from 2.8 to 19.2% in men.14 The incident rate published is 511 cases per annum for every 100,000 inhabitants over 65 years of age15 and a year-on-year increase of close to 1.5% is observed when comparing the rates per 100,000 inhabitants. Approximately 90% of all cases occur in persons over 64 years of age.16

The goal of this paper is to analyze the factors associated with mortality 3 months, 1 year and 2 years after surgery for an osteoporotic hip fracture in patients aged 65 or over.

Material and methodProspective observational study on osteoporotic hip fractures in patients aged 65 or older and operated on in a reference-level hospital with 2 years’ follow-up. Throughout 2010, all patients were consecutively included if they were aged 65 or over and had been operated on for a low-impact hip fracture at what was then the “Virgen del Camino” Hospital in Pamplona, currently known as “Navarre Hospital Complex B”. patients were excluded if they died before the surgical procedure, or if they presented a high energy fracture, or were transferred to other hospitals or regions and it was not possible to maintain follow-up.

Patients were seen by an internal medicine specialist as well as an orthopaedic surgeon. They all received rehabilitation 24h after surgery and a social and family assessment was carried out by the Social Work Department. The patients’ demographic, functional and clinical details were noted, along with any prior treatments and their level of dependency. Patients on anticoagulant therapy had this withdrawn and those receiving anti-platelet medication were switched to 100mg of acetylsalicylic acid from admission. Following removal of the surgical drainage 24h after the procedure, the acetylsalicylic acid was withdrawn from those receiving anti-platelet medication and they were ponce more put on their habitual treatment, as well as maintaining anti-thrombotic prophylaxis for the 30 days following discharge. Those previously receiving anticoagulant therapy were also put back on their regular treatment following removal of the surgical drainage 24h after the procedure. All of them received antibiotic prophylaxis (cephazolin or vancomycin if allergic to beta-lactamases), analgesia, intravenous iron saccharose (200mg or 400mg if Hb<12g/dl), as well as nutritional supplements, vitamin B12, and folates if any deficit was detected.

The information collected included demographic variables (age and gender), their status prior to surgery such as their comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index),17 dependency (Barthel index),18 risk for anaesthesia (ASA scale)19 and analytical results (haemoglobin, creatinine and albumin levels prior to surgery), as well as their progression (complications, blood transfusions, the number of days admitted to hospital and the time to surgery if, in these last two cases, these times were influenced by the type of care received). Note was taken of all cardiac complications (heart failure, acute coronary syndrome and fast ventricular fibrillation), respiratory complications (pulmonary embolism, flare-up of chronic obstructive disease and infections of the lower airways, with or without X-ray imaging), renal complications (reduction in glomerular filtration compared to admission), acute retention of urine, diabetic decompensations, metabolic decompensations (hyponatraemia), urine infections with a positive culture, infections of the surgical wound and acute confusional syndrome as per the criteria of the Confusion Assessment Method.20 A categorical variable entitled “Complications” was created to reflect whether or not they presented any of the complications specified above.

The survival of the patients over the periods analyzed was confirmed by means of their computerized case history.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as their absolute and percentage values while continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviation. Survival was assessed at 90 days, 1 year and 2 years. The mortality-related risk factors were analyzed for all 3 periods by means of a bivariate and multivariate statistical analysis; the level of significance was established at P<0.05. In the comparison of variables according to age and in the bivariate analysis, Pearson's χ2 test was used for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney's U test for continuous variables. The multivariate analysis was performed using Cox's proportional risk model. The dependent variable was the vital status at 3 months, at one year and at 2 years following the surgical procedure. The survival analyses using Cox's regression at 90 days, 1 year and 2 years included, on the one hand, the mortality-related variables in all periods in the bivariate analysis (age in years, dependency according to the Barthel index >60 or ≤60, complications [yes/no] and acute confusional syndrome [yes/no]) and other variables considered clinically relevant such as gender (male/female), ASA score, the Charlson index, pre-surgery haemoglobin (≥12 or <12g/dl) and albumin (≥3.5 or <3.5g/dl). The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS 20.0 software programme.

The possible limitations of the study are selection bias, through including only patients operated on, the scant number of patients, not having recorded any details of variables prior to the procedure and not being multicentric.

The study was proposed as part of a strategy for the improvement of the care provided to elderly patients with hip fracture and multiple pathologies and it was approved by the management of the hospital complex. In the course of the study, the patients were seen by the Orthopaedic Surgery Department at a care unit with the collaboration of the Internal Medicine Department. All patients were seen according to the protocol established at the multidisciplinary care centre for elderly patients admitted for osteoporotic hip fracture without the performance of any other kind of procedure. Data confidentiality was guaranteed through the dissociation of patients’ identification details from their clinical-administrative details, thus complying with the provisions contained in national laws 15/1999 and 41/2002 and in the Navarre Regional Government's law 17/2010 on rights and duties of persons with regard to health matters.

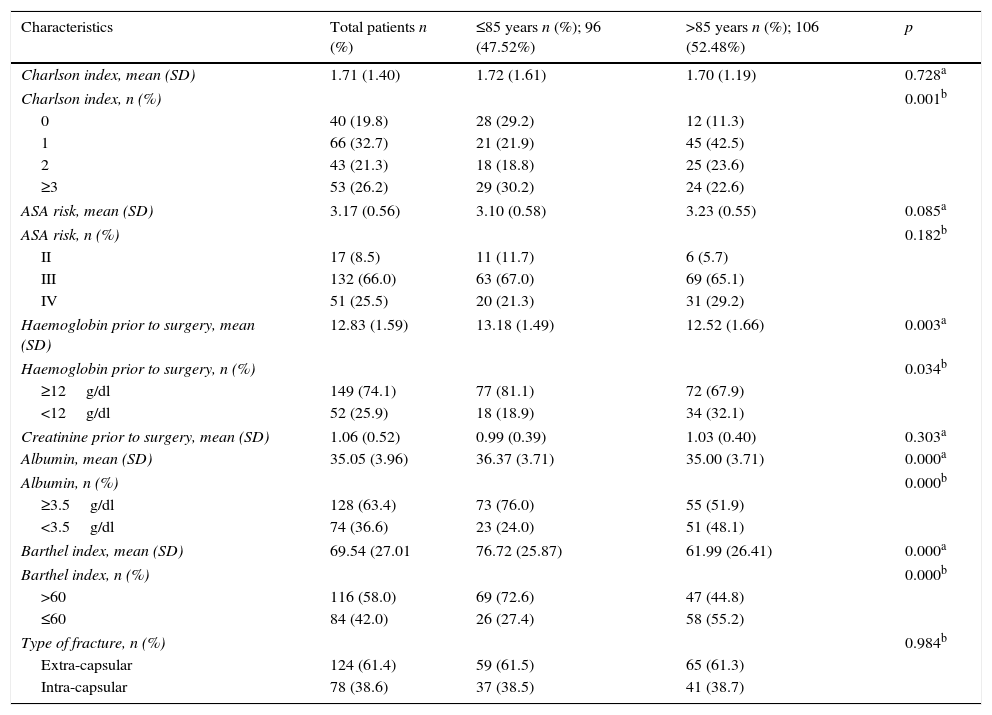

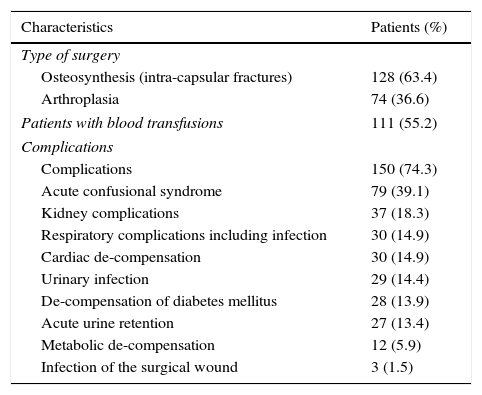

ResultsThe initial cohort was 211 patients; 9 were excluded from the study. Of the patients excluded, 3 died before the surgical procedure, one presented a high-energy fracture, another was transferred to a different hospital before being operated on and 4 were transferred to other regions following discharge from hospital. Ultimately, 202 patients admitted for surgical procedures due to low-impact hip fractures were included. The patients’ mean age and standard deviation was 84.9 (±7.5) years. Of these, 96 (47.5%) were 85 or less and 106 (52.5%) were over 85 years of age. In this series, 164 (81.2%) were female and 38 (18.8%) were male. The mean duration of their admission was 13.7 (4.2) days and the time to surgery was 2.6 (1.3) days. The pre-surgery clinical, analytical and functional details and fracture type are shown in Table 1 and the type of surgery, transfusions and complications in Table 2.

Characteristics of patients prior to surgery.

| Characteristics | Total patients n (%) | ≤85 years n (%); 96 (47.52%) | >85 years n (%); 106 (52.48%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlson index, mean (SD) | 1.71 (1.40) | 1.72 (1.61) | 1.70 (1.19) | 0.728a |

| Charlson index, n (%) | 0.001b | |||

| 0 | 40 (19.8) | 28 (29.2) | 12 (11.3) | |

| 1 | 66 (32.7) | 21 (21.9) | 45 (42.5) | |

| 2 | 43 (21.3) | 18 (18.8) | 25 (23.6) | |

| ≥3 | 53 (26.2) | 29 (30.2) | 24 (22.6) | |

| ASA risk, mean (SD) | 3.17 (0.56) | 3.10 (0.58) | 3.23 (0.55) | 0.085a |

| ASA risk, n (%) | 0.182b | |||

| II | 17 (8.5) | 11 (11.7) | 6 (5.7) | |

| III | 132 (66.0) | 63 (67.0) | 69 (65.1) | |

| IV | 51 (25.5) | 20 (21.3) | 31 (29.2) | |

| Haemoglobin prior to surgery, mean (SD) | 12.83 (1.59) | 13.18 (1.49) | 12.52 (1.66) | 0.003a |

| Haemoglobin prior to surgery, n (%) | 0.034b | |||

| ≥12g/dl | 149 (74.1) | 77 (81.1) | 72 (67.9) | |

| <12g/dl | 52 (25.9) | 18 (18.9) | 34 (32.1) | |

| Creatinine prior to surgery, mean (SD) | 1.06 (0.52) | 0.99 (0.39) | 1.03 (0.40) | 0.303a |

| Albumin, mean (SD) | 35.05 (3.96) | 36.37 (3.71) | 35.00 (3.71) | 0.000a |

| Albumin, n (%) | 0.000b | |||

| ≥3.5g/dl | 128 (63.4) | 73 (76.0) | 55 (51.9) | |

| <3.5g/dl | 74 (36.6) | 23 (24.0) | 51 (48.1) | |

| Barthel index, mean (SD) | 69.54 (27.01 | 76.72 (25.87) | 61.99 (26.41) | 0.000a |

| Barthel index, n (%) | 0.000b | |||

| >60 | 116 (58.0) | 69 (72.6) | 47 (44.8) | |

| ≤60 | 84 (42.0) | 26 (27.4) | 58 (55.2) | |

| Type of fracture, n (%) | 0.984b | |||

| Extra-capsular | 124 (61.4) | 59 (61.5) | 65 (61.3) | |

| Intra-capsular | 78 (38.6) | 37 (38.5) | 41 (38.7) | |

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists.

Characteristics of the surgery and post-surgical characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of surgery | |

| Osteosynthesis (intra-capsular fractures) | 128 (63.4) |

| Arthroplasia | 74 (36.6) |

| Patients with blood transfusions | 111 (55.2) |

| Complications | |

| Complications | 150 (74.3) |

| Acute confusional syndrome | 79 (39.1) |

| Kidney complications | 37 (18.3) |

| Respiratory complications including infection | 30 (14.9) |

| Cardiac de-compensation | 30 (14.9) |

| Urinary infection | 29 (14.4) |

| De-compensation of diabetes mellitus | 28 (13.9) |

| Acute urine retention | 27 (13.4) |

| Metabolic de-compensation | 12 (5.9) |

| Infection of the surgical wound | 3 (1.5) |

Four of the patients (1.98%; 95% CI: 0.77–4.98) died at our hospital, 16 in the first 3 months (7.9%; 95% CI: 4.93–12.48), 39 (19.3%; 95% CI: 14.46–25.30) in the first year and 64 (31.7%; 95% CI: 2566–3839) before the 2-year follow-up.

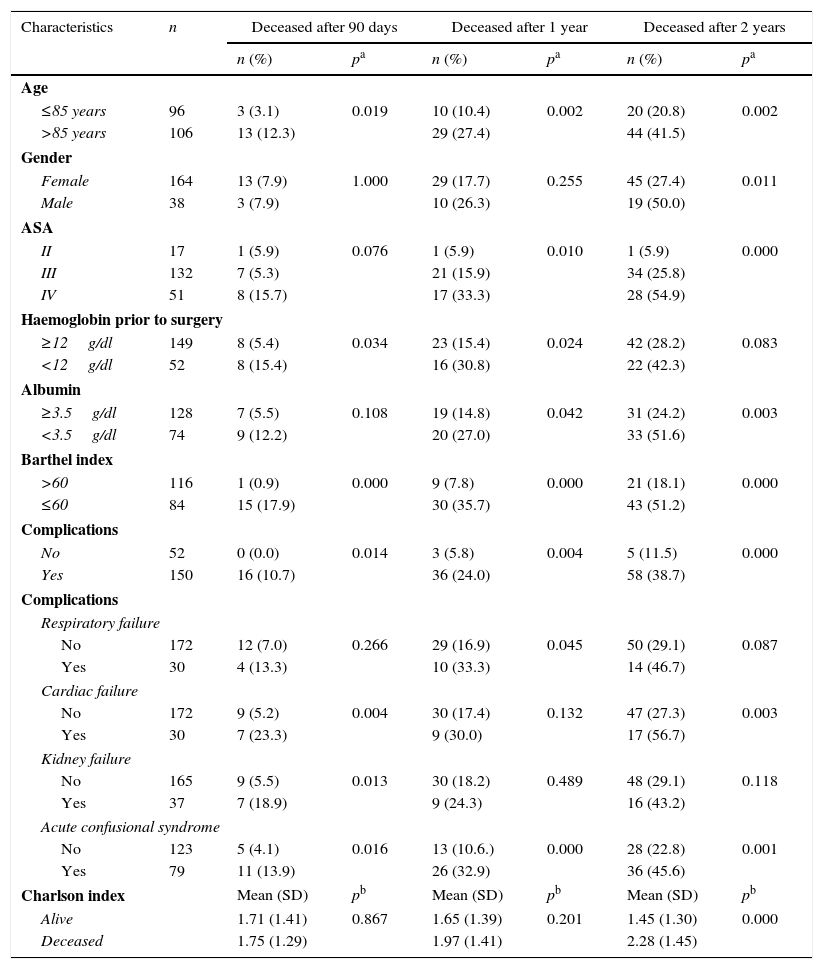

Table 3 reflects all the mortality-associated variables in each of the 3 periods analyzed. Non-existent values can be seen in some cases due to not having recorded, specifically, the Barthel index and the ASA risk of two of the patients and pre-surgical haemoglobin for one of them. Neither the length of their admission nor the time to surgery was associated with greater mortality. The statistical significance for the relationship between the duration of admission and mortality after 90 days, 1 and 2 years was 0.811, 0.393 and 0.856, respectively, while for time to surgery it was 0.573, 0.378 and 0.666, also respectively.

Variables associated with mortality according to a bivariate analysis.

| Characteristics | n | Deceased after 90 days | Deceased after 1 year | Deceased after 2 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | pa | n (%) | pa | n (%) | pa | ||

| Age | |||||||

| ≤85 years | 96 | 3 (3.1) | 0.019 | 10 (10.4) | 0.002 | 20 (20.8) | 0.002 |

| >85 years | 106 | 13 (12.3) | 29 (27.4) | 44 (41.5) | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 164 | 13 (7.9) | 1.000 | 29 (17.7) | 0.255 | 45 (27.4) | 0.011 |

| Male | 38 | 3 (7.9) | 10 (26.3) | 19 (50.0) | |||

| ASA | |||||||

| II | 17 | 1 (5.9) | 0.076 | 1 (5.9) | 0.010 | 1 (5.9) | 0.000 |

| III | 132 | 7 (5.3) | 21 (15.9) | 34 (25.8) | |||

| IV | 51 | 8 (15.7) | 17 (33.3) | 28 (54.9) | |||

| Haemoglobin prior to surgery | |||||||

| ≥12g/dl | 149 | 8 (5.4) | 0.034 | 23 (15.4) | 0.024 | 42 (28.2) | 0.083 |

| <12g/dl | 52 | 8 (15.4) | 16 (30.8) | 22 (42.3) | |||

| Albumin | |||||||

| ≥3.5g/dl | 128 | 7 (5.5) | 0.108 | 19 (14.8) | 0.042 | 31 (24.2) | 0.003 |

| <3.5g/dl | 74 | 9 (12.2) | 20 (27.0) | 33 (51.6) | |||

| Barthel index | |||||||

| >60 | 116 | 1 (0.9) | 0.000 | 9 (7.8) | 0.000 | 21 (18.1) | 0.000 |

| ≤60 | 84 | 15 (17.9) | 30 (35.7) | 43 (51.2) | |||

| Complications | |||||||

| No | 52 | 0 (0.0) | 0.014 | 3 (5.8) | 0.004 | 5 (11.5) | 0.000 |

| Yes | 150 | 16 (10.7) | 36 (24.0) | 58 (38.7) | |||

| Complications | |||||||

| Respiratory failure | |||||||

| No | 172 | 12 (7.0) | 0.266 | 29 (16.9) | 0.045 | 50 (29.1) | 0.087 |

| Yes | 30 | 4 (13.3) | 10 (33.3) | 14 (46.7) | |||

| Cardiac failure | |||||||

| No | 172 | 9 (5.2) | 0.004 | 30 (17.4) | 0.132 | 47 (27.3) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 30 | 7 (23.3) | 9 (30.0) | 17 (56.7) | |||

| Kidney failure | |||||||

| No | 165 | 9 (5.5) | 0.013 | 30 (18.2) | 0.489 | 48 (29.1) | 0.118 |

| Yes | 37 | 7 (18.9) | 9 (24.3) | 16 (43.2) | |||

| Acute confusional syndrome | |||||||

| No | 123 | 5 (4.1) | 0.016 | 13 (10.6.) | 0.000 | 28 (22.8) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 79 | 11 (13.9) | 26 (32.9) | 36 (45.6) | |||

| Charlson index | Mean (SD) | pb | Mean (SD) | pb | Mean (SD) | pb | |

| Alive | 1.71 (1.41) | 0.867 | 1.65 (1.39) | 0.201 | 1.45 (1.30) | 0.000 | |

| Deceased | 1.75 (1.29) | 1.97 (1.41) | 2.28 (1.45) | ||||

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; SD: standard deviation; n: number of patients.

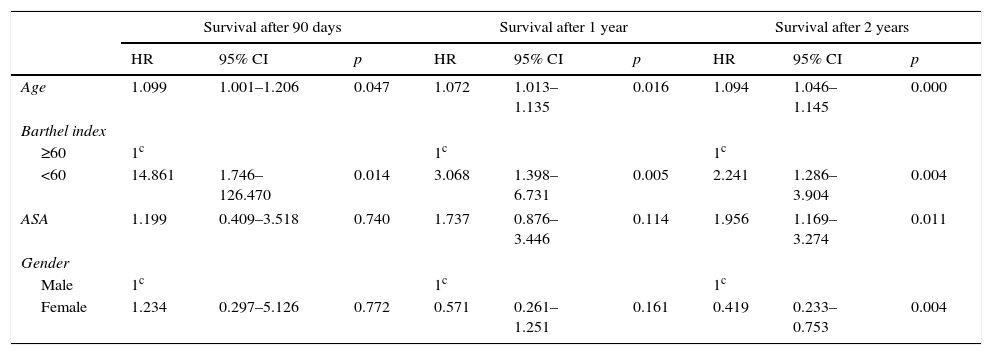

Table 4 shows the variables with a statistically significant relationship with mortality in any of the periods analyzed after performing the survival analysis using Cox's proportional risk model.

Multivariate survival analysis. Independent risk factors for mortality.

| Survival after 90 days | Survival after 1 year | Survival after 2 years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 1.099 | 1.001–1.206 | 0.047 | 1.072 | 1.013–1.135 | 0.016 | 1.094 | 1.046–1.145 | 0.000 |

| Barthel index | |||||||||

| ≥60 | 1c | 1c | 1c | ||||||

| <60 | 14.861 | 1.746–126.470 | 0.014 | 3.068 | 1.398–6.731 | 0.005 | 2.241 | 1.286–3.904 | 0.004 |

| ASA | 1.199 | 0.409–3.518 | 0.740 | 1.737 | 0.876–3.446 | 0.114 | 1.956 | 1.169–3.274 | 0.011 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1c | 1c | 1c | ||||||

| Female | 1.234 | 0.297–5.126 | 0.772 | 0.571 | 0.261–1.251 | 0.161 | 0.419 | 0.233–0.753 | 0.004 |

1c: reference category; ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists; HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: significance (Cox's regression).

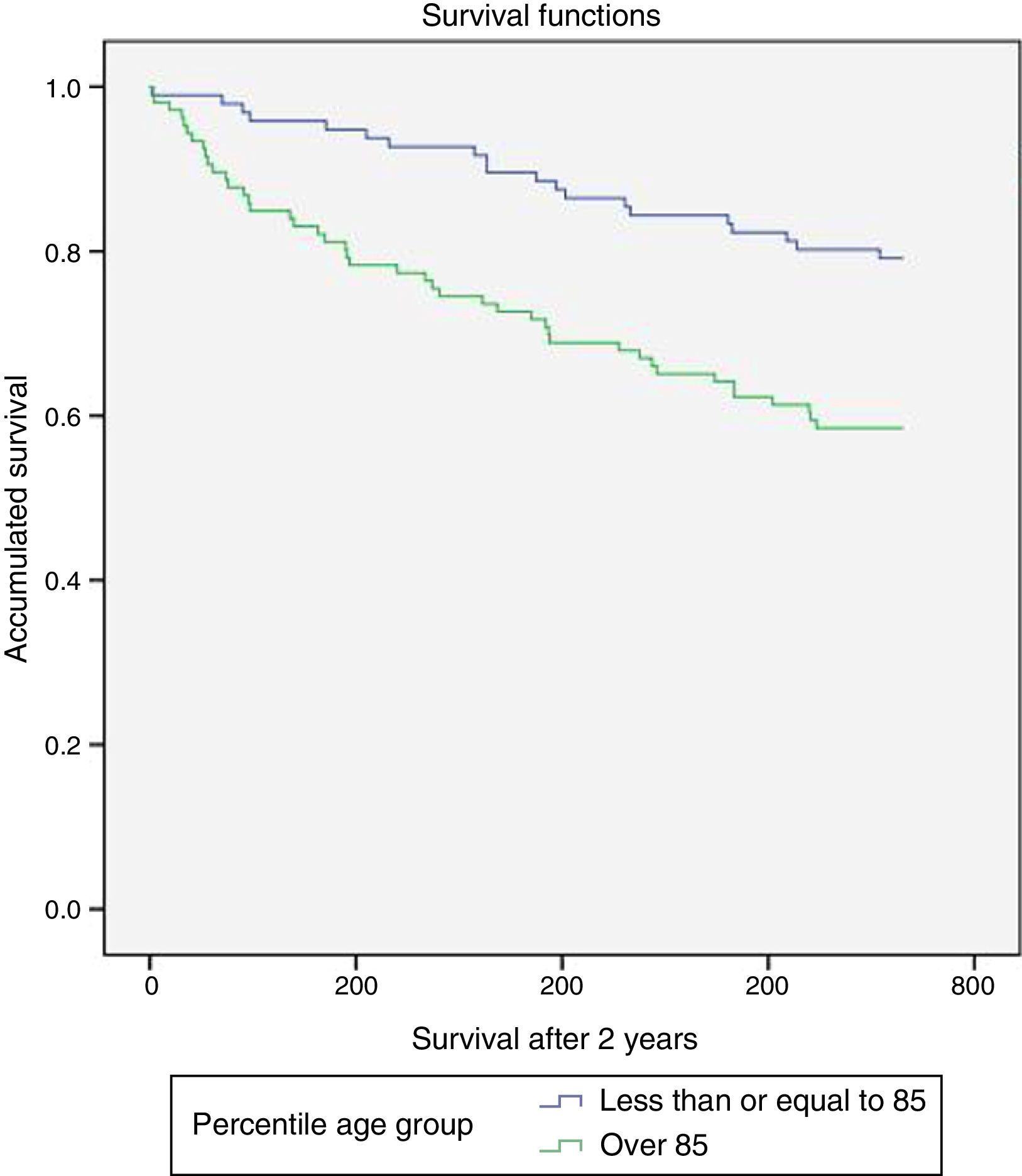

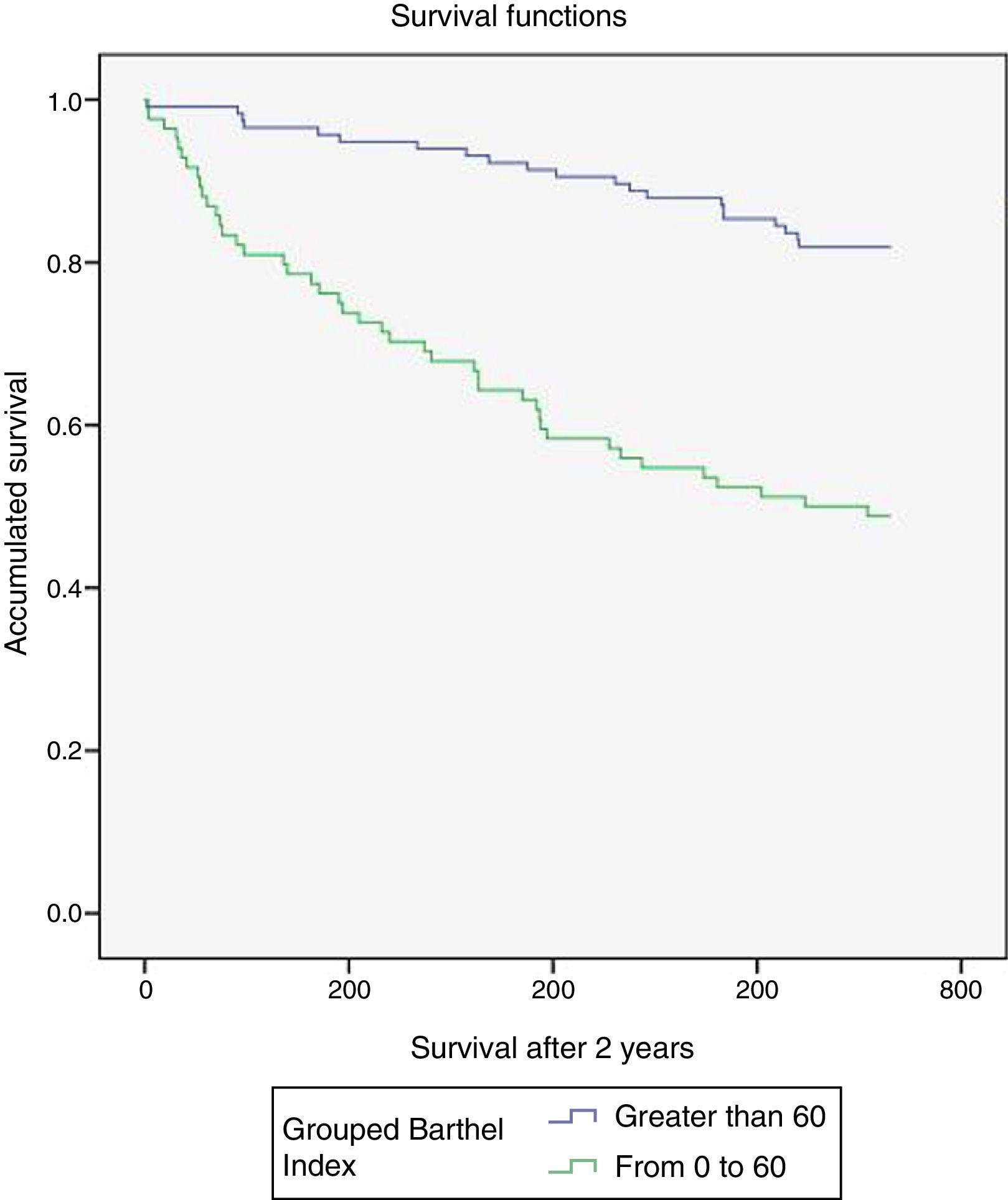

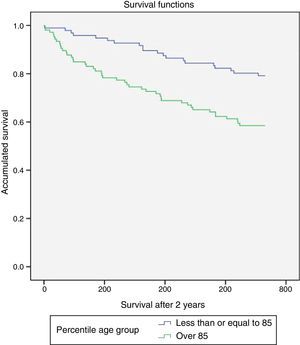

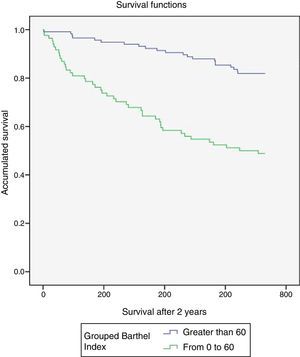

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate the Kaplan–Meier survival curves over the 2 years following the surgical procedure by age and Barthel index. These show statistically significant differences of lower survival at greater age and lower Barthel index score (statistical significance according to the log rank test [Mantel–Cox] was 0.001 and 0.000, respectively).

DiscussionOsteoporotic hip fractures in elderly individuals increase the likelihood of dying, although the age and comorbidity of patients contribute to this. The characteristics of the patients affected by hip fracture in the present study are similar to those published elsewhere.21,22 More than 80% of patients were female and, in general, of advanced age (85 years old on average and more than half of them over this age). Outstanding features included fragility, with moderate to severe dependency in half of the patients, comorbidity (Charlson index≥2) also in half of them and an elevated anaesthesia risk (ASA≥III) in a majority of cases (91.5%). The scant physiological reserve of these patients makes the appearance of complications during admission something to be frequently expected, although the data vary in this regard from one series to another.21,22 In our study, complications were detected in 74.3% of cases. Acute confusional syndrome was the most frequent complication as it affected almost 40% of those operated on (the published percentages are similar and higher: 56%).22

Even considering series of patients receiving multidisciplinary treatment from admission or seen at orthogeriatric units, the mortality data are variable: post-operative intra-hospital mortality22 is up to 5% approximately, rising to 8% after 3 months,9 between 12 and 32% after one year7,8,11,21 and between 30 and 33% after 2 years in a variety of care models.7,23 The mortality figures in our study (1.98% intra-hospital, 7.9% after 3 months, 19.3% after one year and 31.7% after 2 years) are within the ranges of series treated with care models similar to that in place at our centre. Mortality after 3 months provides short-term results without overlapping with the intra-hospital post-surgical period and is usually associated more with the consequences of the fracture episode. Nonetheless, after 1 or 2 years, mortality is related to co-morbidity and the fragility inherent to advanced age.21

Complications (generally speaking, acute confusional syndrome, age and moderate-severe dependency) were associated with mortality in all 3 periods analyzed. Complications presented in three quarters of the patients and avoiding them whenever possible would contribute to a reduction in mortality. Several studies have identified predictive factors for complications such as age,24 dependency,24 elevated Charlson index values,25 low haemoglobin prior to surgery24,26 and the time to surgery.26 Correcting anaemia and trying to shorten the time to surgery might reduce complications and, in consequence, overall mortality.

Acute confusional syndrome is related to greater mortality.20 Predisposing factors20,27 (whether modifiable such as malnutrition, certain drugs, uncorrected visual and auditory deficits, or non-modifiable such as prior cognitive impairment, age, comorbidity, institutionalization and poor functional capacity prior to surgery) and triggering factors20 (time to surgery, immobilization, pain, metabolic alterations such as hyponatraemia, acute urine retention, hypoxia, cardiac de-compensation, certain types of medication and recurrent infections, as well as environmental factors) must be detected and treated, where feasible, as early as possible to prevent more serious conditions.27

The older patients show lower figures for haemoglobin and albumin and are more dependent than the younger ones, however no differences have been found in the comorbidity and ASA risk between these two groups of patients. Of all the mortality risk factors, age and dependency were the only ones found to be independent in all three periods. Each additional year of age represents approximately 10, 7 and 9% higher probability of dying within the 90-day, 1-year and 2-year windows, respectively. With respect to dependency, patients with moderate to severe dependency had a mortality rate approximately 15, 3 and 2 times higher at 90 days, 1 and 2 years, respectively, than those who were not dependent. Age and dependency have also been classified as independent risk factors for mortality in other studies.8 With regard to other variables considered clinically relevant, an elevated Charlson index (described as an independent risk factor for mortality28) was associated in our series with a higher proportion of deceased patients 2 years after the procedure, albeit without being considered an independent risk factor. Male gender and an ASA grade≥III were independent factors predicting mortality 2 years after the surgical procedure. Around twice as many men as women died and each grade in the ASA score doubled the probability of dying in that period. These results agree with those of other studies.15 With respect to laboratory findings, anaemia (haemoglobin <12g/dl) and hypoalbuminaemia (albumin <3.5g/dl) (both detectable and, in many cases, correctable) are related to greater mortality29; in our study they were also related to a higher proportion of deceased patients, although not in all the periods analyzed.

Blood transfusions are not related to greater mortality in any of the periods analyzed, although they had been a predicting factor for mortality in other studies.30 Time to surgery was not related to mortality, as in other series.2 The positive influence in our case may be that most of the patients were operated on in the first 48–72h and that morbimortality has been shown to increase clearly above this time.6 In multidisciplinary units such as the one this study was conducted at, both the time in hospital and the delay before surgery are lower than in units without a multidisciplinary team.21

This study has showcased the complexity of fragile elderly patients affected by low-impact hip fractures when they have multiple pathologies and are susceptible to complications. This patient profile may benefit from comprehensive care by multidisciplinary teams of co-ordinated orthopaedic surgeons and internal medicine specialists or experts in geriatric care who identify the patients at greatest risk, detect problems early and prescribe treatment, which may even lower the mortality in the short term (one month)10 and in the longer term (one year).8,11,21 The factors that were most determinant for mortality were age and dependency: both these parameters are easy to measure and allow identification from admission of patients more susceptible to having poor progress and potentially benefiting from more exhaustive care.

Level of evidenceLevel IV evidence.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that no experimentation has been conducted on human beings or animals for the purposes of this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that this article contains no patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that this article contains no patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Aranguren-Ruiz MI, Acha-Arrieta MV, Casas-Fernández de Tejerina JM, Arteaga-Mazuelas M, Jarne-Betrán V, Arnáez-Solis R. Factores de riesgo de mortalidad tras intervención quirúrgica de fractura de cadera osteoporótica en pacientes mayores. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:185–192.