To compare outcomes and complications when performing bone lengthening with two different techniques: isolated external fixation versus external fixation combined with intramedullary nail.

Material and methodComparative retrospective study of 30 cases of tibial lengthening divided in two symmetrical groups. Cases were matched based on several variables to maximise homogeneity between the groups.

Variables used for comparison were external fixation time, external fixation index, rate of consolidation, clinical outcomes, complications and range of joint motion.

ResultsMean external fixation time was 2.08 months in the group lengthened with nail while the standard group showed 5.85 months (p<0.0001). Mean external fixation index was 0.42 months per centimetre in the nail group compared with 1.15 in the group without nail (p<0.0001). There were no significant differences in the rate of consolidation (1.23 months per centimetre against 1.15) or in terms of clinical outcomes. We found differences in the rate of complications (1.2 per patient to 2.6) in favour of the technique with nail. There were no differences in the range of motion of ankle joint.

Discussion and conclusionsLengthening over an intramedullary nail is more effective than using external fixation alone for tibial lengthening with regard to time of external fixation, index of external fixation and complication rate. We found no advantages in terms of consolidation and joint mobility.

Comparar resultados y complicaciones al realizar elongaciones óseas con dos métodos diferentes: fijación externa aislada versus fijación externa sobre clavo intramedular.

Material y métodoEstudio comparativo retrospectivo de 30 casos de elongación tibial divididos en dos grupos simétricos. Los casos se emparejaron en función de una serie de variables para maximizar la homogeneidad entre los grupos.

Las variables utilizadas para la comparación fueron el tiempo de fijación externa, el índice de fijación externa, el índice de consolidación, los resultados clínicos, las dificultades y el rango de movilidad articular.

ResultadosEl tiempo medio de fijación externa fue de 2,08 meses en el grupo alargado sobre clavo, frente a los 5,85 del grupo estándar (p < 0,0001). La media del índice de fijación externa fue de 0,42 meses por centímetro en el grupo de clavo frente a los 1,15 del grupo sin clavo (p < 0,0001). No hubo diferencias significativas en el índice de consolidación (1,23 meses por centímetro frente a 1,15) ni en cuanto a los resultados clínicos. Se aprecian diferencias en la tasa de complicaciones (1,2 por paciente frente a 2,6) en favor de la técnica con clavo. No hay diferencias en el rango de movilidad articular del tobillo.

Discusión y conclusionesLa elongación sobre clavo intramedular es más efectiva que la fijación externa aislada para alargamientos tibiales en cuanto al tiempo de fijación externa, índice de fijación externa y tasa de complicaciones. No se han demostrado sus ventajas en cuanto a índice de consolidación y movilidad articular.

External fixation has been and continues to be the most common method of bone lengthening because of its minor invasiveness which enables corrections on multiple planes and the possibility it offers to the surgeon for undertaking secondary corrections or altering mounting rigidity at will.

However, the fixators are not exempt from problems. Their use is only viable in patients who collaborate to maintain appropriate hygiene (to avoid infections), and the transfixion of musculature and soft tissues may lead to the appearance of stiffness or severe muscle contractions. We should also mention the discomfort involved for the patient, living with an external device which impedes daily activities and may be an added psychological complexity. Another specific problem of the external fixators is deciding on the appropriate removal time as early removal may lead to bone regeneration fracture.

One of the routes followed aimed at reducing external fixation time and improving clinical outcomes is the technique known as lengthening over nail [LON]. The procedure consists of placing an intramedullary nail without impeding the simultaneous implantation of the external fixator and practising osteotomy. The nail helps to encourage lengthening from the inside of the canal, theoretically reducing axial deviations, and stabilising the bone by blocking it once the distraction phase has been completed. The fixator may thus be removed without waiting for bone healing, with the hope that this will minimise the problems associated with the use of this device. Different studies published have found significant differences between the use of the LON technique and the traditional technique without assistance from intramedullary implant.1–5 The author systematically analysed and compared the results obtained in tibial elongations using the LON method and the standard external fixator lengthening (EFL). The objective of this article is to study the differences between both methods to confirm the hypothesis in accordance with the intramedullary nail assisted distraction osteogenesis (LON) is a more effective therapeutic procedure than the isolated external fixator lengthening (EFL) for tibial elongations.

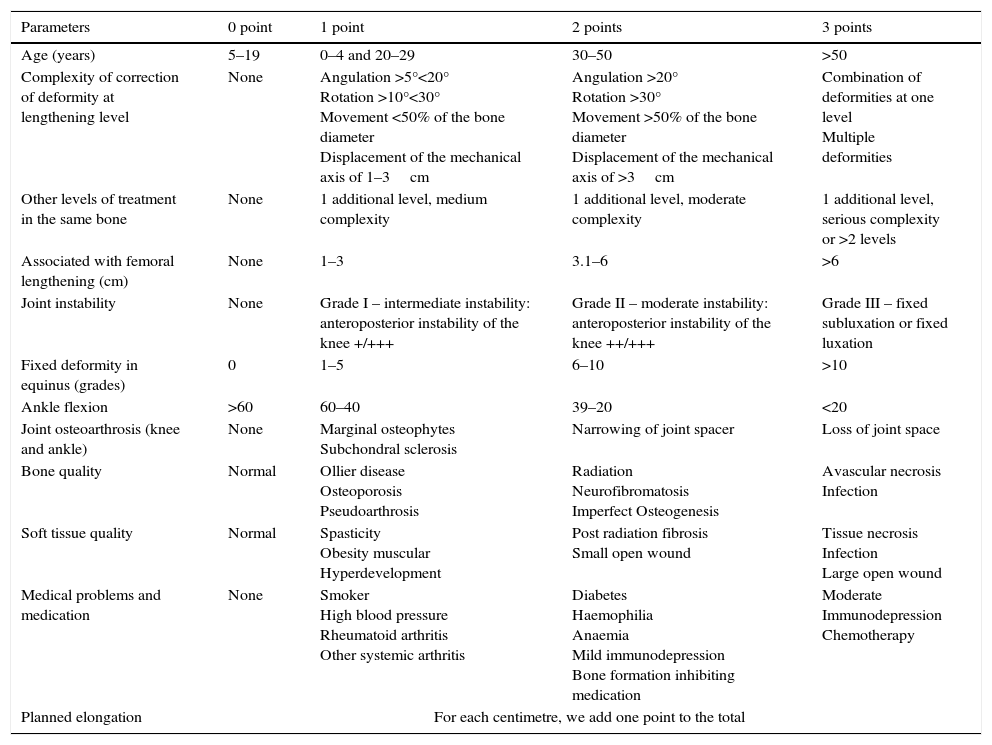

Material and methodsIn order to make a valid comparison between the LONG and EFL, we made a retrospective study of 15 tibial elongations carried out with each technique. Variability between patients and pathologies hindered analysis and for this reason the difficulty and risk of each case was classified on a scale based on 12 parameters approved by the scientific community,1 modified for tibial lengthening. The parameters are shown in Table 1.

Scale of classification of level of procedure difficulty.

| Parameters | 0 point | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 5–19 | 0–4 and 20–29 | 30–50 | >50 |

| Complexity of correction of deformity at lengthening level | None | Angulation >5°<20° Rotation >10°<30° Movement <50% of the bone diameter Displacement of the mechanical axis of 1–3cm | Angulation >20° Rotation >30° Movement >50% of the bone diameter Displacement of the mechanical axis of >3cm | Combination of deformities at one level Multiple deformities |

| Other levels of treatment in the same bone | None | 1 additional level, medium complexity | 1 additional level, moderate complexity | 1 additional level, serious complexity or >2 levels |

| Associated with femoral lengthening (cm) | None | 1–3 | 3.1–6 | >6 |

| Joint instability | None | Grade I – intermediate instability: anteroposterior instability of the knee +/+++ | Grade II – moderate instability: anteroposterior instability of the knee ++/+++ | Grade III – fixed subluxation or fixed luxation |

| Fixed deformity in equinus (grades) | 0 | 1–5 | 6–10 | >10 |

| Ankle flexion | >60 | 60–40 | 39–20 | <20 |

| Joint osteoarthrosis (knee and ankle) | None | Marginal osteophytes Subchondral sclerosis | Narrowing of joint spacer | Loss of joint space |

| Bone quality | Normal | Ollier disease Osteoporosis Pseudoarthrosis | Radiation Neurofibromatosis Imperfect Osteogenesis | Avascular necrosis Infection |

| Soft tissue quality | Normal | Spasticity Obesity muscular Hyperdevelopment | Post radiation fibrosis Small open wound | Tissue necrosis Infection Large open wound |

| Medical problems and medication | None | Smoker High blood pressure Rheumatoid arthritis Other systemic arthritis | Diabetes Haemophilia Anaemia Mild immunodepression Bone formation inhibiting medication | Moderate Immunodepression Chemotherapy |

| Planned elongation | For each centimetre, we add one point to the total | |||

Interpretation: normal: 0–6 points, moderate: 7–11 points, severe: 12 points or more.

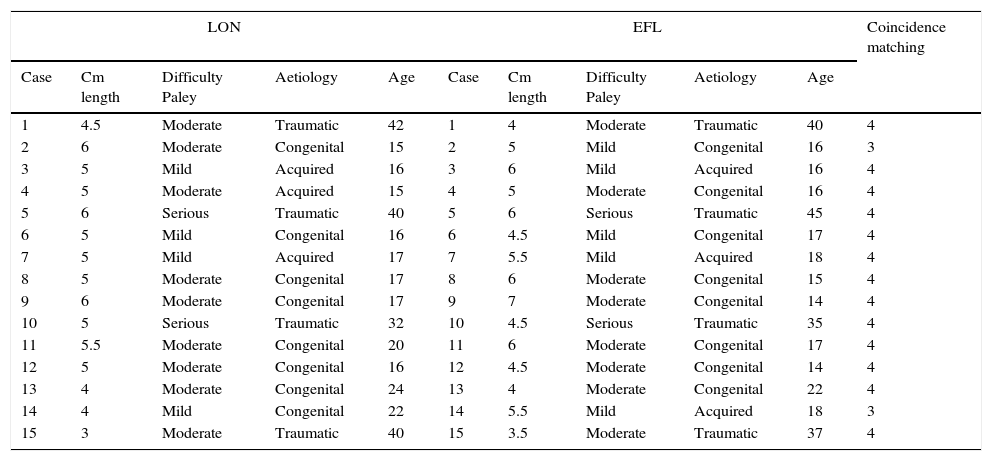

Fifteen patients treated between February 2003 and December 2013 were taken as the study sample Mean time of follow-up was 2.5 years (range between 2 and 10 years). The mean patient age at surgery was 23.06 years (range between 15 and 42 years). Seven patients were male and eight female. The 15 patients treated for discrepancy in limb length and the aetiology of their dissymmetries may be viewed in Table 2.

Matching of cases of elongations by LON and EFL techniques.

| LON | EFL | Coincidence matching | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Cm length | Difficulty Paley | Aetiology | Age | Case | Cm length | Difficulty Paley | Aetiology | Age | |

| 1 | 4.5 | Moderate | Traumatic | 42 | 1 | 4 | Moderate | Traumatic | 40 | 4 |

| 2 | 6 | Moderate | Congenital | 15 | 2 | 5 | Mild | Congenital | 16 | 3 |

| 3 | 5 | Mild | Acquired | 16 | 3 | 6 | Mild | Acquired | 16 | 4 |

| 4 | 5 | Moderate | Acquired | 15 | 4 | 5 | Moderate | Congenital | 16 | 4 |

| 5 | 6 | Serious | Traumatic | 40 | 5 | 6 | Serious | Traumatic | 45 | 4 |

| 6 | 5 | Mild | Congenital | 16 | 6 | 4.5 | Mild | Congenital | 17 | 4 |

| 7 | 5 | Mild | Acquired | 17 | 7 | 5.5 | Mild | Acquired | 18 | 4 |

| 8 | 5 | Moderate | Congenital | 17 | 8 | 6 | Moderate | Congenital | 15 | 4 |

| 9 | 6 | Moderate | Congenital | 17 | 9 | 7 | Moderate | Congenital | 14 | 4 |

| 10 | 5 | Serious | Traumatic | 32 | 10 | 4.5 | Serious | Traumatic | 35 | 4 |

| 11 | 5.5 | Moderate | Congenital | 20 | 11 | 6 | Moderate | Congenital | 17 | 4 |

| 12 | 5 | Moderate | Congenital | 16 | 12 | 4.5 | Moderate | Congenital | 14 | 4 |

| 13 | 4 | Moderate | Congenital | 24 | 13 | 4 | Moderate | Congenital | 22 | 4 |

| 14 | 4 | Mild | Congenital | 22 | 14 | 5.5 | Mild | Acquired | 18 | 3 |

| 15 | 3 | Moderate | Traumatic | 40 | 15 | 3.5 | Moderate | Traumatic | 37 | 4 |

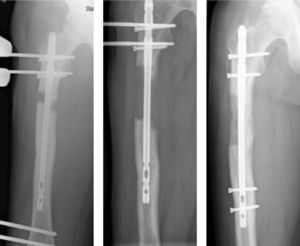

In all cases the same type of external monolateral fixator was used (Monotube Triax, Stryker; Kalamazoo, U.S.A.) and an identical intramedullary nail (T2, Stryker; Kalamazoo, U.S.A.), with anterograde insertion and cut two centimetre above its diameter. Osteotomy was always performed under tibial tuberosity and resected 1cm from the fibula in 12 cases, and with a plain percutaneous osteotomy in the other three cases. The distal tibiofibular joint was temporarily fixed using an osteosynthesis nail in 14 cases and Kirschner wires in the others. Fixation was applied with the ankle in dorsiflexion to prevent loss of movement in the ankle. It is important to use Kirschner wires and cannulated drill bits to guide us prior to implanting the most compromised screws so that there is no contact with the nail. No prophylactic elongation of the Achilles tendon was practised in any case (Fig. 1).

Tibial elongations using isolated external fixation lengthening (EFL)Given that the number of patients treated with EFL was higher than that treated with LON, the standard selection criteria was applied aimed at maximising comparability between both groups. For this, and after making the cases anonymous, they were classified in accordance with the amount of lengthening, their age, the aetiology of their pathology and the level of difficulty in accordance with the Paley criteria modified for the tibia. From here, the different patients we matched if there were three or more coincidences in these four parameters analysed. Thus 10 of the patients were comparable in the four criteria and another five in three (Table 2).

The patients were treated between May 2002 and December 2013 and their mean clinical follow-up was 3.5 years (range between 2 and 10 years). The mean age at the time of surgery was 22.66 years (range between 14 and 45 years) and there were 7 males and 8 females. Thirteen of the lengthening procedures were due to dissymmetry whilst the remaining two were performed on a short patient. The aetiologies of their conditions are shown in Table 2.

The fixators used were the LRS system (Orthofix; Bussolengo, Italy) in nine tibias, Monotube Triax (Stryker; Kalamazoo, U.S.A.) in three and TrueLok (Orthofix; Bussolengo, Italy) in the remaining three. The osteotomy was performed under the tibial tuberosity in 13 cases, was diaphysaria in another and in the distal third in the others. 1cm of fibia was resected in 14 cases, with a simple percutaneous osteotomy in the others. The distal tibiofibular joint was temporarily fixed using an osteosynthesis screw in 13 cases and with a Kirschner wire in the other two. Prior to fixing the tibiofibular mortise the ankle was placed in dorsiflexion to reduce possible loss of movement. No prophylactic elongation of the Achilles tendon was practised in any case (Fig. 2).

Variables studied for comparing LON with EFLIn order to discern the clinical differences between the two methods of lengthening considered we have to quantify the measurement of a series of variables which are relevant for assessing treatment benevolence. In line with the existing references we chose the following:

- •

External fixation time. Months passing between insertion and removal of external fixator.

- •

External fixation index (EFI). Defined as the time of external fixation divided by elongated length, measure in centimetres.

- •

Consolidation index (CI). Calculated as the months passing between surgery and bone consolidation divided between the lengthened centimetres. Consolidation was considered completed when the X-rays confirmed that at least three of the four corticals were intact or completely ossified.6,7

- •

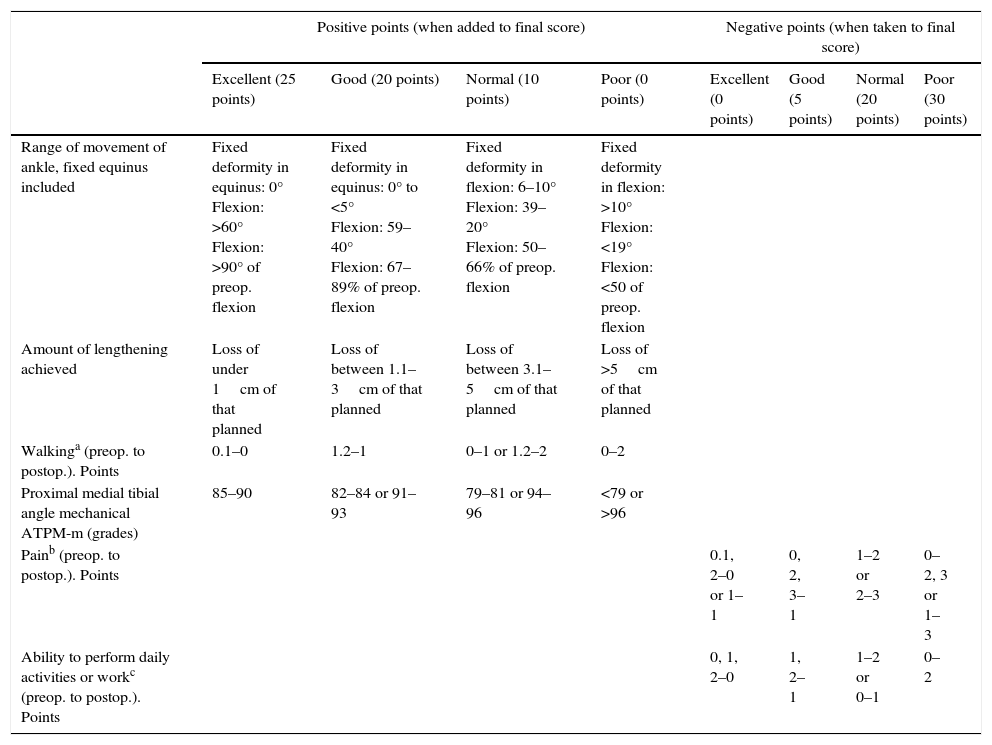

Evaluation of clinical and radiologic outcomes. In line with existing literature we have followed the classification made by Paley for the femur1 distinguishing excellent, good, normal and poor results with several minor modifications to adapt it to tibial elongations. The scale and parameters used are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.Point scale for clinical and radiologic outcome of tibial lengthening.

Positive points (when added to final score) Negative points (when taken to final score) Excellent (25 points) Good (20 points) Normal (10 points) Poor (0 points) Excellent (0 points) Good (5 points) Normal (20 points) Poor (30 points) Range of movement of ankle, fixed equinus included Fixed deformity in equinus: 0°

Flexion: >60°

Flexion: >90° of preop. flexionFixed deformity in equinus: 0° to <5°

Flexion: 59–40°

Flexion: 67–89% of preop. flexionFixed deformity in flexion: 6–10°

Flexion: 39–20°

Flexion: 50–66% of preop. flexionFixed deformity in flexion: >10°

Flexion: <19°

Flexion: <50 of preop. flexionAmount of lengthening achieved Loss of under 1cm of that planned Loss of between 1.1–3cm of that planned Loss of between 3.1–5cm of that planned Loss of >5cm of that planned Walkinga (preop. to postop.). Points 0.1–0 1.2–1 0–1 or 1.2–2 0–2 Proximal medial tibial angle mechanical ATPM-m (grades) 85–90 82–84 or 91–93 79–81 or 94–96 <79 or >96 Painb (preop. to postop.). Points 0.1, 2–0 or 1–1 0, 2, 3–1 1–2 or 2–3 0–2, 3 or 1–3 Ability to perform daily activities or workc (preop. to postop.). Points 0, 1, 2–0 1, 2–1 1–2 or 0–1 0–2 Excellent: 95–100 points; good: 75–94 points; normal: 40–74 points; poor: under 40 points.

- •

Difficulties. We adhered to the division made by Paley8 regarding problems, obstacles and complications. The problems are defined as difficulties which require a non surgical intervention for resolution; obstacles which require surgical intervention for resolution and the complications which may be intraoperative or problems which cannot be resolved prior to the end of treatment.

- •

Joint balance. The range of ankle movement was analysed, measured at several times during treatment and with the knee flexed to relax calf tension. Values between 0° and 60° were taken.

According to El-Husseini et al.3 and Guo et al.,4 the external fixation index (EFI) for the control group of the tibia (bony lengthening performed only with external fixation) is 1.23month/cm; we expected to reduce this EFI by one point to 0.23 for the bone lengthening group with intramedullary nail assisted external fixation. For a confidence level of 95% and a strength of 80% we would require 12 patients per group and adjusted to 15% of losses we would need 15 patients.

We performed a descriptive study in which the numerical variables were summarised as a mean, typical deviation and range. For qualitative variables frequencies and percentages were used.

We did this both for the group of elongations using isolated external fixation lengthening (EFL) and for the intramedullary nail assisted external fixation (LON). The first group was considered to be the control group and the second the intervention group.

For contrast of hypotheses and their objectives, after studying the normality of distribution of the continuous variables using the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test, we used the student's t-test for normality and the non-parametric test for the contrary (U-Mann–Whitney) with the Wilcoxon for paired samples.

For the qualitative variables we used the Chi-square test with the Yates correction when necessary and a typified residue study for analysing the address of the associations.

All the results will be considered significant for a p<0.05 level. Analyses were performed with the SPSS version 19.0 software programme.

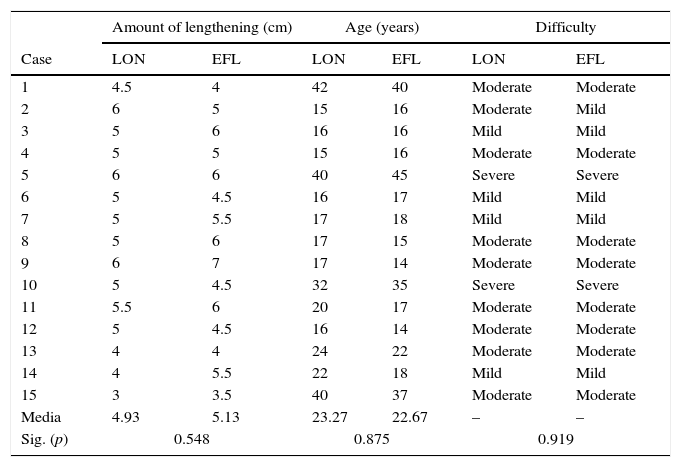

ResultsPrior to beginning analysis of results, we confirmed that the groups were comparable with one another. For this we analysed parameters such as the amount of lengthening, age or level of difficulty of the procedure. The comparative is displayed in Table 4.

Comparability between the groups.

| Amount of lengthening (cm) | Age (years) | Difficulty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | LON | EFL | LON | EFL | LON | EFL |

| 1 | 4.5 | 4 | 42 | 40 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 2 | 6 | 5 | 15 | 16 | Moderate | Mild |

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 16 | Mild | Mild |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 16 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 5 | 6 | 6 | 40 | 45 | Severe | Severe |

| 6 | 5 | 4.5 | 16 | 17 | Mild | Mild |

| 7 | 5 | 5.5 | 17 | 18 | Mild | Mild |

| 8 | 5 | 6 | 17 | 15 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 9 | 6 | 7 | 17 | 14 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 10 | 5 | 4.5 | 32 | 35 | Severe | Severe |

| 11 | 5.5 | 6 | 20 | 17 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 12 | 5 | 4.5 | 16 | 14 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 13 | 4 | 4 | 24 | 22 | Moderate | Moderate |

| 14 | 4 | 5.5 | 22 | 18 | Mild | Mild |

| 15 | 3 | 3.5 | 40 | 37 | Moderate | Moderate |

| Media | 4.93 | 5.13 | 23.27 | 22.67 | – | – |

| Sig. (p) | 0.548 | 0.875 | 0.919 | |||

There were no differences in the mean amount of tibial elongation achieved (p=0.548). In the LON group it was 4.93cm (range between 3 and 6cm) compared with 5.13cm (range between 3.5 and 7cm) in the control group.

There were no age differences between the groups either (p=0.875). This was 23.27 years in the LONG group (range between 15 and 42 years) and 22.67 in the other group (range between 14 and 45 years).

Lastly, after analysing the level of difficulty between the groups, it was not possible to confirm that there had not been any significant difference (p=0.919).

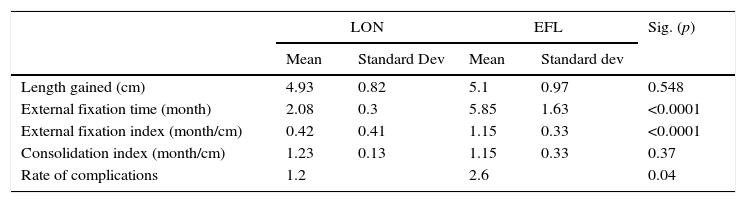

After these preliminary analyses, we may confirm that the groups may be comparable to one another and we can go through to analyse the results obtained (Table 5).

Compared outcomes.

| LON | EFL | Sig. (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Dev | Mean | Standard dev | ||

| Length gained (cm) | 4.93 | 0.82 | 5.1 | 0.97 | 0.548 |

| External fixation time (month) | 2.08 | 0.3 | 5.85 | 1.63 | <0.0001 |

| External fixation index (month/cm) | 0.42 | 0.41 | 1.15 | 0.33 | <0.0001 |

| Consolidation index (month/cm) | 1.23 | 0.13 | 1.15 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Rate of complications | 1.2 | 2.6 | 0.04 | ||

The mean time for insertion of the fixator was significantly lower in the LON cases (p<0.0001), with 2.08months (range between 1.5 and 2.63months) compared with 5.85months (range between 3.86 and 10months).

As a consequence, the external fixation index mean (EFI) was also significantly lower in the LON group (p<0.0001). The values recorded were 0.42months for each elongated centimetre (range between 0.372 and 0.52month/cm) compared with 1.15 (range between 0.81 and 1.86month/cm).

Consolidation indexIts mean was 1.23months per centimetre (range between 1 and 1.5month/cm) for the LON group and 1.15months per centimetre (range between 0.81 and 1.86month/cm) for the EFL group. We were not able to confirm significant differences between the groups (p=0.370), since it appears that the time it takes for the bone to heal is similar with both types of treatment.

Clinical resultsIn the LON group 8 excellent results were recorded and 7 good ones. In the control group they achieved 10 excellent results, 4 good ones and one normal. There were no poor results in any group. Clinically there was no statistically significant difference on comparing both surgical techniques in our series. (p=0.361).

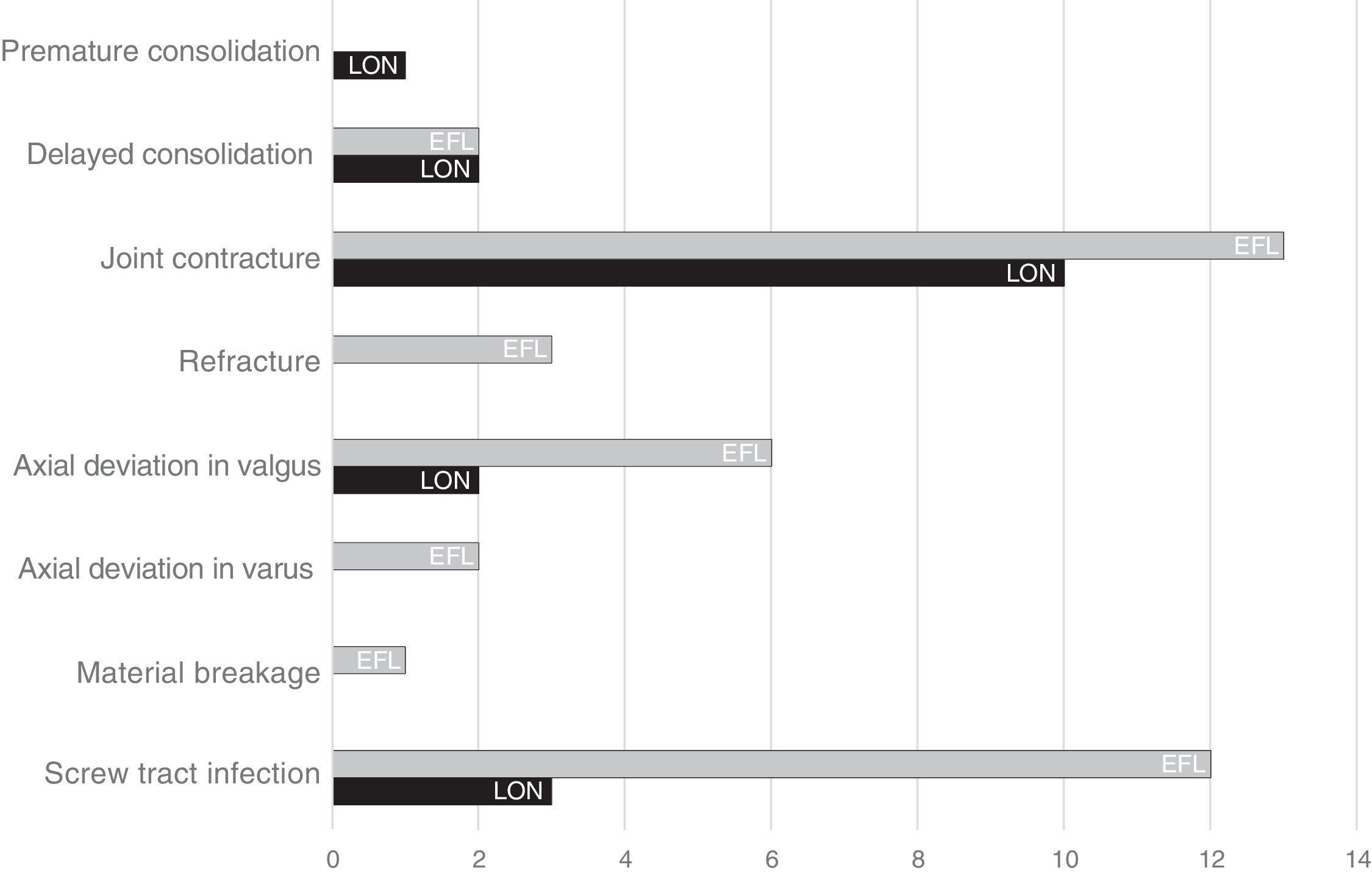

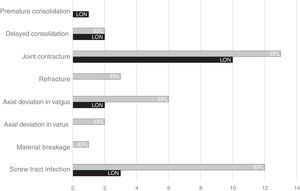

Problems, obstacles and complicationsAnalysis of the difficulties entailed during treatment (classified as problems, obstacles and complications) are contained in Fig. 3. Taken as a whole and as a mean, each of the LON patients suffered 1.2 difficulties, with this rate rising to 2.6 per patient in lengthening without intramedullary nail assistance. This difference was considered statistically significant with a p<0.05.

In more detail, in the intervention group we found a total of 18 difficulties, including 8 problems, 7 obstacles and 3 complications. In the control group we found there were 39 difficulties, including 17 problems, 12 obstacles and 10 complications.

In order to find out what type of difficulties are the most frequent in each technique, analysis according to typology could be summarised as follows:

- •

Axial deviations. These are significantly more frequent (p=0.02) in the control group (8 compared with 2).

- •

Joint contractures. There were no differences between groups (p=0.409). In the LON group we found 10 contractures compared with 13 in the EFL group.

- •

Infection of the screw tract. This occurred more frequently in the control group (12 cases) than in the LON group (3 cases), with p<0.0001. The mean of number of screws per segment used in the LON group was 4, whilst in the other group it was 5.86 (range between 4 and 9).

- •

Fractures of regenerated bone. Although in the control group three fractures of regenerated bone presented and none in the LON group, the difference was not significant (p=0.068).

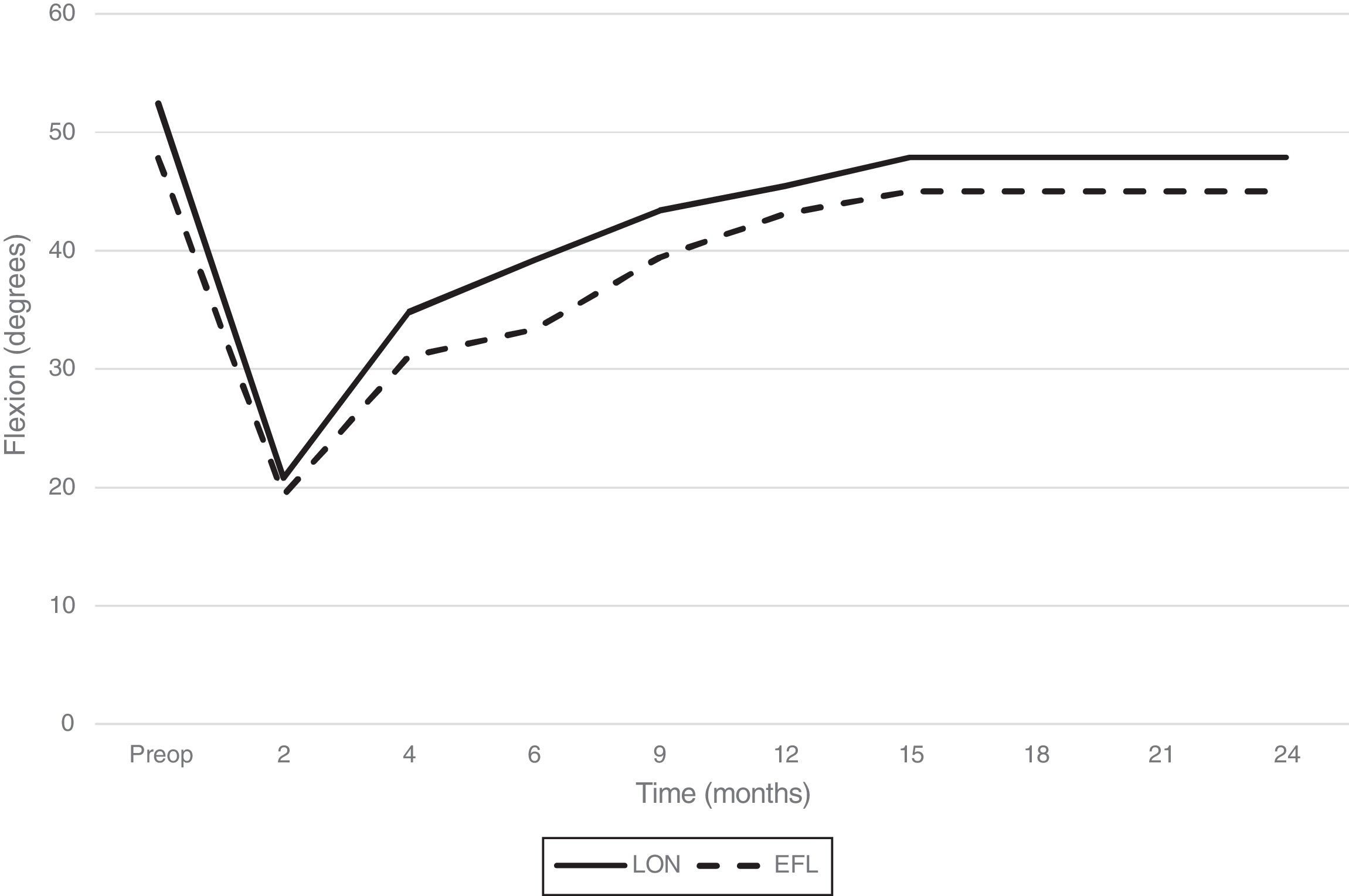

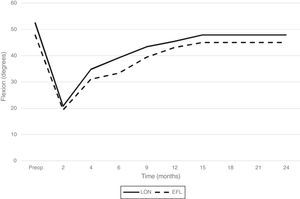

For the group of tibias elongated with the LON technique, the preoperative mean flexion was 52.43° and for the EFL group it was 47.86°, with no significant differences being found between them (p=0.423).

In the intervention group the joint mobility was again measured at the end of distraction, with flexion being 20.79°, 39.64% of initial mobility. Eight weeks after the removal of the external fixator the measurement was repeated, which revealed a value of 34.7842° (66.34% of initial mobility). At the end of the consolidation phase a mean of 39.21° was recorded (74.79% of initial mobility) and 24 months after surgery it was 47.85° (91.28% of initial mobility).

In the control group, mean flexion at the end of the distraction phase was 19.36° (40.33% of initial mobility). For obvious reasons, no corresponding measurement was made eight weeks after removal of the fixator. At the end of the consolidation phase a value of 33.35° was recorded (69.69% of initial mobility) and after the 24 month follow-up the mean was 45° (93% of initial mobility).

The difference in the values recorded at the end of the distraction and consolidation phase was not statistically significant (p=0.567 and p=0.157, respectively), and neither of the two therefore demonstrated a faster rehabilitation.

All previous measurements were repeated at 9, 12, 15 and 24 months after surgery. The evolution of the ankle mobility for the two methods compared may be viewed in Fig. 4.

DiscussionDespite the fact that our study was limited by retrospective analysis, statistical comparison of the groups considered allow us to confirm that they were homogeneous as regards age, aetiology, elongated centimetres and degree of difficulty (parameter which covers the other 12 variables). We may therefore now study of the different variables put forward to compare the two study techniques.

External fixation time, external fixation index and consolidation indexExternal fixation time (EFT) was lower in the LON group (2.08 months compared with 5.86 months; p<0.0001). The same occurred with the external fixation index (EFI) (p<0.0001). These results are also concordant with other studies published about the same subject.4,9

We reviewed the literature to find out what influence the canal over-milling had on regeneration consolidation, confirming that it appeared to have positive effects in this respect.10 We always try to mill 2mm above the size of the nail to use this to our advantage and to aid segment slippage. In our series we obtained a consolidation index (CI) of 1.23 months per centimetre in the LON group and of 1.5cm in the EFL group, with no significant differences existing between the two (p=0.366). In the literature we found reports of elongation over nail which had obtained similar values to our series. Specifically, in the works of Kim et al.11 who exhibited a CI of 1.7 months per centimetre, and in Bilen et al.,12 of 1.26 per centimetre. The before-mentioned study of Guo et al.4 did not reveal any significant differences regarding consolidation index between the two groups compared.

El-Husseini et al.3 presented a comparative prospective and randomised study between these techniques. It is not directly comparable with our series since elongations in femur and tibia are missed but they also found differences in EFT and EFI, whilst consolidation times were similar for both groups. Jain and Harwood10 reached these same conclusions in a systematic review on LON tibial lengthening.

Clinical outcomeWe have confirmed that from a statistical point of view, there do not appear to be any differences in clinical outcome (measured according to the scale modified by Paley) on using one technique or another. For this, we many state that, with regard to the functional results, the patient is indifferent to whether one or another technique is applied.

Problems, obstacles and complicationsIn general, we may state that analysis of our series reveals a higher rate of complications in the group of non nail assisted lengthening. The article by Guo et al.4 states the same, but Jain and Harwood10 found no clear differences between the two groups.

Notwithstanding, if we study the comparisons with regards to typology, we find several particularities worthy of mention. One of the most common difficulties in this type of treatment is the joint contracture of ankle equinus, and our study found no statistically significant differences between both groups (p=0.409). Analysis of the literature led us to similar conclusions. Kim et al.11 detected a tendency of equinus in 58 of their 80 elongations, despite the intensive use of physiotherapy. Standard solutions to this problem are the lengthening of the fascia of the calves or the Achilles tendon. It is also useful to reduce the speed of distraction and in very severe cases, to block ankle articulation using a cross bridge.

In our series we applied temporary blocking of the ankle in certain pathologies such as fibular hemimelias submitted to elongations above 5cm and with no intramedullary nail assistance. Out of the three patients treated like this, we confirmed that two did not develop the feared joint contracture and a third did, although the latter already had reduced ROM and previous equinus.

There appears to be a relationship between the magnitude of lengthening (understood as a percentage of the increase in bone length) and the possibility of having to lengthen the triceps surae muscle. Kim et al.11 states that in a subgroup of elongations of the tibia by LON with over 20% increase in length, only 5% of patients had to have operations to relax the triceps surae muscle. In contrast, in the subgroup of lengthenings by EFL with over 20% increase in length, up to 95% of patients needed relaxation of the triceps surae muscle or for a cross bridge to be added to the foot. In our series, for LON cases, we found there were 4 problems and 6 obstacles related to joint contractures, leading to an occurrence rate for this event of 0.66. For cases of EFL we had 7 problems, 4 obstacles and 2 complications, with an occurrence rate of 0.86. The difference is not significant (p=0.409) and therefore both the analysis of our series as well as that of the literature suggests that the losses of mobility in tibial elongations are more closely related to the amount of centimetres to be elongated than to the technique applied.

We found no differences between both methods in functional ankle recovery. The range of movement was the same during follow-up and at the end of treatment in both groups, which is consistent with that recorded in the literature.4

Joint deviations are another circumstance which may negatively alter the outcome of a tibial elongation. In our series we found significant differences in favour of the LON technique (p=0.02). It appears logical that, on carrying out distraction on an internal tutor, good alignment is made. However, in the literature we may find angular deviations, particularly in varus or valgus.11,13

The tendency for deviation in valgus produced by tibial lengthening is a proven reality and several factors may explain it. One is the difference between the tibia distraction and the fibular distraction. Also, the greater strength of the tissues in the posterolateral region of the tibia lead to greater tension in that direction. With regard to the use of nails as internal tutors of elongation, the fact that its diameter is reduced or the proximal fragment is unstable may lead to the appearance of this type of difficulty. Several authors have suggested the use of Poller screws to centre the implant in the canal, thus attempting to minimise desaxations.

Although our series was short, we found two residual deviations in valgus but these lacked any medical relevance.

Screw tract infection of the fixator poses a certain amount of risk in LON lengthening, as the possibility exists that the intramedullary nail spreads this local infection, leading to deep osteomyelitis. Fortunately, there are several factors which have reduced infection rates. Among them we may point out the general use of hydroxyapatite coated screws, the limitation of the number of screws to an average of four per elongated bone and the reduced time of external fixation. In cases of LON in our series we found three cases of infection of the screw tract. Two were superficial (problems) and were treated with oral anti-biotherapy, whilst the third was interpreted s a latent infection (complication) and presented one and a half years after the fixator was removed (treated with local abscess drainage and anti-biotherapy). For the series of lengthening without nails, three infections were classified as obstacles (removal of the affected screw and antibiotherapy) and another nine were considered problems. The increase in the occurrence of infections in this series was due to the larger number of screws per segment and the longer external fixation time required to complete treatment. There were no cases of deep infection after two years of follow-up.

We found no nerve damage in any of our groups. Nogueira et al.14 found 9.3% of nerve damage in a series of 814 cases and which, of the patients in whom nerve damage would found, 70% required nerve decompression. This did not occur in our case.

In our series we were also able to confirm a lower number of bone regeneration fractures, although the skeletal maturity of the patients was not taken into account. We considered that, in one patient with the epiphyseal plate open, undertaking an anterograde tibial interlocking could damage the growth cartilage and generate a recurvatum of the limb. As a result the LON technique is not valid for patients undergoing growth (girls under 10–12years of age and boys between 12 and 14).14,15

ConclusionsIn our study we compared tibial lengthening made using the external fixator with others which combined this fixator with an intramedullary nail.

Analysis of our series and of the literature consulted allowed us to make a series of affirmations when comparing both techniques:

- •

External fixation time is considerably lower in the case of lengthening made using the LON technique.

- •

The external fixation index (understood as the time necessary for inserting the fixator by the elongated unit) was also lower in the case of intramedullary LON.

- •

The use or non use of an intramedullary nail had no implications on the time necessary for bone consolidation.

- •

Although it is true that additional surgery may be involved for removing the intramedullary implant, in our environment we do not do this systematically and we only extract it if the patient suffers discomfort.

- •

Assisted external fixation with intramedullary nail presents with a lower rate of complications compared with isolated external fixation.

- •

Functional recovery of the ankle joint is similar in both elongation techniques.

Due to all the above, and based on the results previously published by different authors,4,5,16 together with data provided by our study on the clinical and radiologic effects of bone elongation in the tibia, we may confirm that the osteogenesis to distraction using intramedullary nail is a more effective therapeutic procedure than isolated external fixation for elongations of the tibia with regards to external fixation time, external fixation index and complication rate, whilst its advantages regarding clinical outcome, consolidation index and joint mobility have not been demonstrated.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been performed on humans or animals in this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Salcedo Cánovas C. Alargamiento óseo tibial mediante fijación externa. Estudio comparativo entre la técnica tradicional y la asistida por clavo intramedular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:8–18.