The aim of the present study is to present a transcultural adaptation and validation of the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index questionnaire into Spanish (Spain), and to assess its psychometric properties.

Material and methodsThe transcultural adaptation was conducted according to sequential forward and backward translation approach. A pilot study was subsequently performed to ensure acceptable psychometric properties. The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index questionnaire was administered to 79 patients twice within a period of 2 months, and patients were stratified into 3 groups (cohorts).

Results-

Structural validation: valid, though uneven results were obtained regarding the structure of the 4 domains of the original questionnaire.

-

Criterion validity: Pearson's correlation coefficient: ROWE: 0.74; EQ-5D-5L: 0.471.

-

Internal consistency: Cronbach's alpha: 0.96; coefficient of intraclass correlation: 0.949.

-

Sensitivity to change: t-Student ⿿ t: 42.38; standard response means: 2.69; effect size: 2.61; standard error of measurement: 23%; minimal detectable change: 76%. No floor or ceiling effects were detected.

The Spanish version of the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index questionnaire is a valid, reliable tool, and highly sensitive to change to assess patients with shoulder instability.

El propósito del presente trabajo es presentar la adaptación transcultural y validación realizada del cuestionario Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index al idioma español (España), así como la evaluación de sus propiedades psicométricas.

Material y métodosLa adaptación transcultural se realizó mediante la técnica de traducción y retrotraducción. Posteriormente se realizó una prueba piloto y se ponderaron las propiedades psicométricas. Se evaluaron 79 pacientes que cumplimentaron el cuestionario Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index en el periodo de 2 meses y se estratificaron estadísticamente en 3 grupos diferentes (cohortes).

Resultados-

Validez estructural: ofreció un resultado válido, aunque dispar de la estructura de 4 dominios del cuestionario original.

-

Validez de criterio: coeficiente de correlación de Pearson: 0,745 (ROWE) y 0,471 (EQ-5D-5L).

-

Consistencia interna: alfa de Cronbach: 0,96, test-retest (ICC): 0,949.

-

Sensibilidad al cambio: t-Student: 42,38; respuesta promedio estandarizada (SRM): 2,69; tamaño del efecto (ES): 2,61; error estándar de medición (SEM): 23%; mínimo cambio detectable (SDC): 76%. No se halló efecto suelo o techo.

La versión española del cuestionario Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index ofrece una herramienta válida, confiable y con una alta sensibilidad al cambio para la valoración de pacientes afectos de inestabilidad de hombro.

Recurrent luxation of the shoulder with a prevalence of approximately 2% in the general population frequently presents in almost 60% of patients under 20 years of age.1

Medical professionals have some difficulty in studying shoulder instability because once dislocation has been reduced, pain and range of movement are not usually affected. Patients complain of subjective characteristics such as apprehension and lack of confidence in their shoulder when carrying out sports activities or in their everyday lives.

A stable shoulder may result from treatment of this condition and for this reason assessment by these patients, whether pre or postoperatively, cannot solely be based on objectives issues such as the number of recurrences, range of movement or muscle strength.2

Specific quality of life questionnaires, currently also called PROM,3 allow the patient to express subjective issues and express how the condition has affected everyday life activities from different angles, whether these be regarding their profession, involvement in sports or their emotional well-being.

The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index questionnaire (WOSI) (appendix 1), which was described by Kirkley, Griffin et al.4 in 1998 was designed for the study of patients with shoulder instability. It was based on the methodology reported by Kirschner and Guyatt5 and in its original version in English (Canada) it offers a correct design and methodology. It contains 21 items which are divided into 4 sections:

- (1)

Physical symptoms (10 items).

- (2)

Sports, recreation and work activities (4 items).

- (3)

Lifestyle (4 items).

- (4)

Emotional well-being (3 items).

Each item responds to a 100mm VAS with a maximum total score amounting to 2100 (where 0 is the best possible score and 2100 is the worst). A percentage result may obtained by calculation with the following equation: score obtained: 2100/2100ÿ100.

This questionnaire has been recommended and tested in different studies as a diagnostic and follow-up tool for patients with shoulder instability.6,7 It has been culturally adapted and validated in different languages8⿿13 and it has been used and administered online6⿿8 and by telephone13. The EQ-5D-5L14 and ROWE15 questionnaires were used to assess the psychometric properties of the adapted document.

The aim of this study is to present cultural adaptation, validation into the Spanish language and assessment of the psychometric properties in keeping with the international regulations of the Medical Outcome Trust.16

Material and methodTranslation, back-translation and cultural adaptation of the questionnaireThe questionnaire was culturally adapted in different phases (Fig. 1) in keeping with internationally accepted recommendations17,18 and the translation and back-transition technique.19

TranslationTwo bilingual people were involved in this process, one of them specialised in English grammar although not in the health area, and the other a doctor specialising in orthopaedics. Both of them translated the original WOSI questionnaire independently. Once both translations had been completed meetings were held to reach a consensus regarding a single final translation.

Back-translationOnce a single translation was obtained a double back-translation was made, i.e. two separate translations from the original language.

This double back-translation was completed by two different professionals to the ones who had done the initial translation and the same work pattern was repeated. Both did a back-translation independently, resulting in two documents. The necessary consensus meetings were then convened to obtain a single back-translation.

At this stage it is important that the back-translation obtained may be available to the author/s of the original questionnaire, as was also our case, in order to compare the original linguistic meaning intended in the phrases or items. Doctor Griffin suggested several corrections which were included in the document prior to final presentation.

Pilot testThe Spanish version of the WOSI questionnaire was assessed with regards to comprehension, clarity and familiarity using cognitive interviews with probing and paraphrasing methodology.20,21

With this in mind, it was distributed to 10 patients (7 men and 3 women). Five of them completed the self-administered questionnaire after a brief explanation on how to go about it and with a clarification document to hand in order to later complete an interview for analysis of the items. The remaining five patients participated in an interview where the meaning of each item was explained prior to responding to it.

Several clarifications were given, particularly regarding the significance of the following terms expressed: clicking, cracking, snapping, stiffness, feeling of instability, and the difference between lack of strength and lack of resistance.

Contrary to what we imagined regarding the translation and adaptation of item 17 where the conceptual translation would have been ⿿roughhousing⿿ or ⿿horsing around⿿ and we translated this as ⿿jugar a pelear⿿ (pretend fighting), the term was understood in all cases.

The major items on the questionnaire were generally well understood and all patients completed it within a mean time of 14min.

Final versionConsensus meetings were held with all members of the work group. The linguistic equivalence of the back-translation was compared with the original questionnaire and to do this the linguistically adapted items were compared with the original version in English and classified in accordance with the assessment scale proposed by Alonso et al.22 as follows:

-

Type A: totally equivalent.

-

Type B: fairly equivalent, but with a few doubtful words or expressions.

-

Type C: with more than two different words or expressions and dubious equivalence.

Particular attention was paid to type B and C items.

When checking the back-translation with the original questionnaire, the scores obtained were:

-

Two items were classified as type C (10%: 2 out of 21) or of doubtful equivalence (items 9 and 17).

-

Eleven items (52%: 11 out of 21) were classified as type B or with a few doubtful words or expressions (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 14, 15 and 20).

-

Eight items were classified as type A (38%: 8 out of 21) with total equivalence (items 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 19 and 21).

A final version (Table 1) was then obtained.

Linguistic equivalence of the transcultural adaptation of the WOSI questionnaire in its Spanish version.

| P. | Original version | Linguistic adaptation | Equiv. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | How much pain do you experience in your shoulder with overhead activities? | ¿Cuánto dolor siente en el hombro con las actividades que requieren elevar los brazos por encima de la cabeza? | B |

| 2 | How much aching or throbbing do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánto dolor o punzadas siente en el hombro? | B |

| 3 | How much weakness or lack of strength do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta debilidad o pérdida de fuerza siente en el hombro? | B |

| 4 | How much fatigue or lack of stamina do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánto cansancio o falta de resistencia siente en el hombro? | B |

| 5 | How much clicking, cracking or snapping do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuántos chasquidos, crujidos o resaltes sienten en el hombro? | B |

| 6 | How much stiffness do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta rigidez siente en el hombro? | B |

| 7 | How much discomfort do you experience in your neck muscles as a result of your shoulder? | ¿Cuántas molestias siente en los músculos del cuello debido al hombro? | B |

| 8 | How much feeling of instability or looseness do you experience in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta sensación de inestabilidad o laxitud siente en el hombro? | B |

| 9 | How much do your compensate for your shoulder with other muscles? | ¿Cuánto compensa con otros músculos la pérdida de fuerza de su hombro? | C |

| 10 | How much loss of range of motion do you have in your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta pérdida de movilidad siente en el hombro? | A |

| 11 | How much has your shoulder limited the amount you can participate in sports or recreational activities? | ¿Cuánto limita el hombro su participación en actividades deportivas o recreativas? | A |

| 12 | How much has your shoulder affected your ability to perform the specific skills required for your sport or work? (If your shoulder affects both sports and work, consider the area that is most affected.) | ¿Cuánto afecta el hombro a su capacidad para realizar las tareas propias de su trabajo o deporte? (Si el hombro afecta tanto al trabajo como al deporte, piense en la que resulta más afectada) | A |

| 13 | How much do you feel the need to protect your arm during activities? | ¿Cuánta necesidad siente de proteger el brazo durante sus actividades? | A |

| 14 | How much difficulty do you experience lifting heavy objects below shoulder level? | ¿Cuánta dificultad experimenta al levantar objetos pesados por debajo del nivel del hombro? | A |

| 15 | How much fear do you have of falling on your shoulder? | ¿Cuánto miedo tiene de caer sobre el hombro? | B |

| 16 | How much difficulty do you experience maintaining your desired level of fitness? | ¿Cuánta dificultad experimenta en mantener el nivel de forma física que desea? | A |

| 17 | How much difficulty do you have ⿿roughhousing⿿ or ⿿horsing around⿿ with family or friends? | ¿Cuánta dificultad tiene para realizar «actividades bruscas» con la familia y amigos (como jugar a pelear)? | C |

| 18 | How much difficulty do you have sleeping because of your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta dificultad experimenta para dormir a causa del hombro? | A |

| 19 | How conscious are you of your shoulder? | ¿Cuánto está usted pendiente de su hombro? | A |

| 20 | How concerned are you about your shoulder becoming worse? | ¿Cuánto le preocupa que el hombro pueda empeorar? | B |

| 21 | How much frustration do you feel because of your shoulder? | ¿Cuánta frustración le produce el hombro? | A |

Following the framework of Salomonson8 patients were classified into three groups, the intention being to reach the highest percentage of variability with regards to the pathology under study:

Group 1: N: 21This was the healthy sample benchmark group.

During the third quarter of 2014 thirty physiotherapy students with no previous background of shoulder problems or instabilities, were requested to complete the WOSI and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires. Two months later, the same students were requested to complete it again. A total of 21 students responded: (5 were removed due to incompletion of some of the questionnaire questions and 4 for not participating in the second questionnaire). Eight women (38%) and 13 men (62%) took part, with a mean age of 18.

Group 2: N: 21Between 2014 and 2015, a study was made of the patients who had had an episode of traumatic scapula-humeral luxation and for which they had presented at and were treated by the emergency services of our hospital with closed reduction and immobilisation of the affected arm. A control X-ray was performed immediately following reduction.

The sample requisite was to have had a luxation episode with a minimum evolution of 2 years prior to the commencement of the study. These patients were given appointments and attended the emergency services between 2012 and 2013.

During the second half of 2015 the patients were initially contacted by phone and were asked to attend the health centre to be assessed by a specialist in shoulder surgery. During this assessment visit they were requested to complete the WOSI and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires and they were clinically examined and asked to complete the ROWE questionnaire. Two months later they were again requested to have a clinical examination and again completed the WOSI and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires. They were also given a physical examination and asked to complete the ROWE questionnaire.

The sample included 21 patients: 4 women (19%) and 17 men (81%). The mean age was 32.3 years (range from 19⿿52 years).

Group 3: N: 37All the patients in this Group were examined in our hospital due to presentation with glenohumeral instability. At the close of study (October 2015), 20 of them (54%) were randomly chosen to undergo surgical intervention by the same team.

Prior to surgery all patients completed the WOSI questionnaire and the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire on quality of life. The healthcare specialist carried out a clinical examination and completed the ROWE questionnaire.

Six months later, the same process as described above was repeated only on the patients who had undergone surgery (20 in total).

The sample included 19 men (94%) and 1 woman (6%). The mean age was 23.58 years (range from 16 to 39 years).

In 8 patients (44%) the arm operated on did not coincide with their dominant hand. 6 of them (75%) were operated on the left shoulder with their dominant hand being the right hand.

At the close of the study 17 patients in Group 3 had not undergone surgery. Inclusion dates were from 11/14 until 10/2015. The sample included 18 men (95%) and 1 woman (5%). The mean age was 26.21 years (range from 16 to 43 years).

Inclusion criteria- (1)

Over 16 years of age.

- (2)

Symptoms of any form of shoulder instability (anterior, posterior or multidirectional).

- (1)

Lacking command of the Spanish (Castilian) language.

- (2)

Patients with genoid or proximal humeral fractures (patients with Hill Sachs or bony Bankart lesions (<20% were included).

- (3)

Patients who had received treatment or follow-up for the said problem in a different hospital.

- (4)

Patients with neurological and/or rheumatic type lesions of the upper limb.

All participants in the study were voluntary and gave their written documented consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí (Sabadell).

The psychometric properties of regarding validity, reliability and sensitivity to change recommended by the Medical Outcome Trust were chosen as a means of comparison with the original study. These included: Pearson's correlation coefficient, the interclass correlation coefficient ICC), the test-retest coefficient, the Cronbach alpha coefficient, the Student's t-test, the size effect, the standardised response mean [SRM]), standard error measurement (SEM), standard detectable change (SDC) and the floor and ceiling effects.

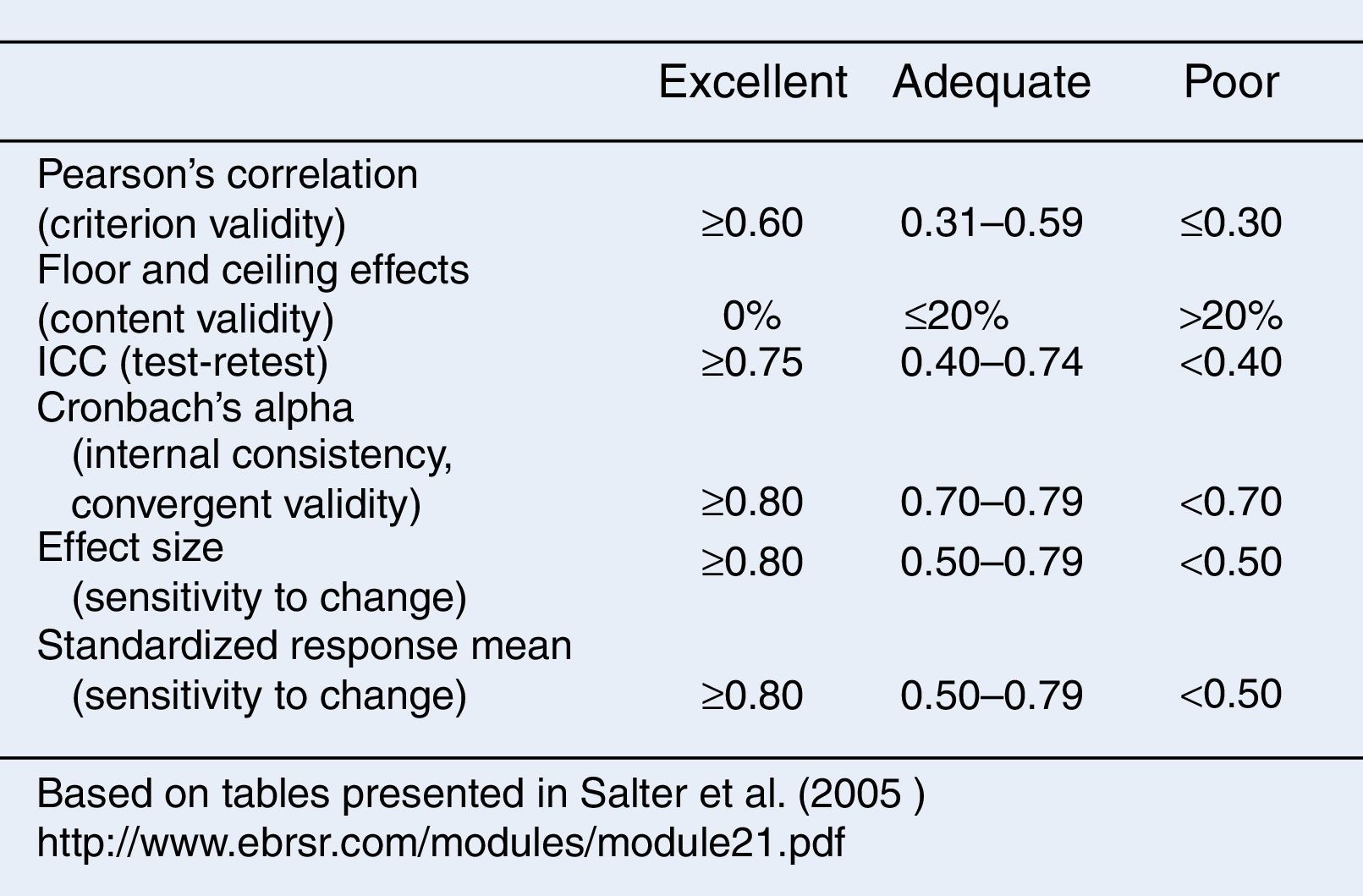

References of the previously mentioned values were taken from Salter et al. (Fig. 2) who established a grading of results to define their psychometric quality and to classify them as poor, adequate or excellent.

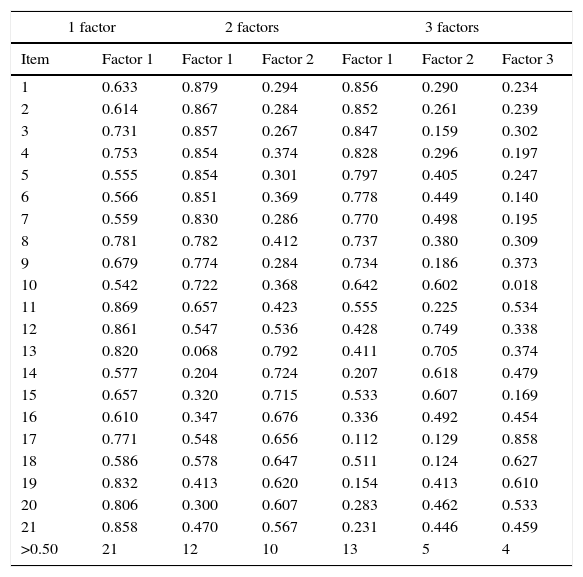

ResultsStructural validityThis was defined as the degree to which the scores of an assessment tool are a suitable reflection of dimension (expected number of subscales or dominions) of the construct to be measured. In the Spanish version weighting was performed using factorial analysis with a varimax rotation method (Table 2).

Factorial analysis of the Spanish version of the WOSI questionnaire with a Varimax matrix rotation method.

| 1 factor | 2 factors | 3 factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

| 1 | 0.633 | 0.879 | 0.294 | 0.856 | 0.290 | 0.234 |

| 2 | 0.614 | 0.867 | 0.284 | 0.852 | 0.261 | 0.239 |

| 3 | 0.731 | 0.857 | 0.267 | 0.847 | 0.159 | 0.302 |

| 4 | 0.753 | 0.854 | 0.374 | 0.828 | 0.296 | 0.197 |

| 5 | 0.555 | 0.854 | 0.301 | 0.797 | 0.405 | 0.247 |

| 6 | 0.566 | 0.851 | 0.369 | 0.778 | 0.449 | 0.140 |

| 7 | 0.559 | 0.830 | 0.286 | 0.770 | 0.498 | 0.195 |

| 8 | 0.781 | 0.782 | 0.412 | 0.737 | 0.380 | 0.309 |

| 9 | 0.679 | 0.774 | 0.284 | 0.734 | 0.186 | 0.373 |

| 10 | 0.542 | 0.722 | 0.368 | 0.642 | 0.602 | 0.018 |

| 11 | 0.869 | 0.657 | 0.423 | 0.555 | 0.225 | 0.534 |

| 12 | 0.861 | 0.547 | 0.536 | 0.428 | 0.749 | 0.338 |

| 13 | 0.820 | 0.068 | 0.792 | 0.411 | 0.705 | 0.374 |

| 14 | 0.577 | 0.204 | 0.724 | 0.207 | 0.618 | 0.479 |

| 15 | 0.657 | 0.320 | 0.715 | 0.533 | 0.607 | 0.169 |

| 16 | 0.610 | 0.347 | 0.676 | 0.336 | 0.492 | 0.454 |

| 17 | 0.771 | 0.548 | 0.656 | 0.112 | 0.129 | 0.858 |

| 18 | 0.586 | 0.578 | 0.647 | 0.511 | 0.124 | 0.627 |

| 19 | 0.832 | 0.413 | 0.620 | 0.154 | 0.413 | 0.610 |

| 20 | 0.806 | 0.300 | 0.607 | 0.283 | 0.462 | 0.533 |

| 21 | 0.858 | 0.470 | 0.567 | 0.231 | 0.446 | 0.459 |

| >0.50 | 21 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 5 | 4 |

Internal consistency was analysed. This is understood to be the degree to which the items on a single scale or dominion can be interrelated and how they assess the same situation or problem on the presumption that if several items measure the same attribute or dimension then they have to be intercorrelated. This correlation may be measured using the Cronbach alpha coefficient, which in our case was 0.96 for the total (0.88⿿0.94 for the different dimensions) (Table 3).

Results of the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the Spanish version of the WOSI questionnaire.

| Dimensions of the WOSI questionnaire | Before (n=79) | After (n=60) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical examination | 0.918 | 0.919 |

| Sports/recreation/work | 0.914 | 0.893 |

| Lifestyle | 0.856 | 0.884 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.940 | 0.905 |

| Total | 0.968 | 0.964 |

Reliability, which is understood to consist of the stability over time of observations measured by the test-retest method, indicates the degree to which the same results are obtained after repeated administrations of a certain tool, when there is no change. The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) is the statistical test used to assess this (Table 4).

Results of test-retest coefficient of the WOSI Spanish version questionnaire.

| Dimensions of the WOSI questionnaire | Test-retest coefficient (ICC) (n=42) | Confidence interval 95% | Significance ⿿P⿿ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical examination | 0.976 | 0.956⿿0.987 | 0.000 |

| Sports/recreation/work | 0.974 | 0.953⿿0.986 | 0.000 |

| Lifestyle | 0.972 | 0.948⿿0.985 | 0.000 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.969 | 0.943⿿0.983 | 0.000 |

| Total | 0.949 | 0.988⿿0.997 | 0.000 |

ICC: interclass coefficient correlation.

The criteria of Salter et al.23 suggest that values oscillate between 0.969 for the emotional well-being dimension and 0.949 for the overall score (P: 0.000) thus presenting correct psychometric eligibility.

Criterion-related validityThis indicates the degree to which the scores of the questionnaire correlate with other questionnaires (or tools) which measure the same trait or variable. Criterion validity was tested by determination of the relationship between the overall score of the WOSI questionnaire and the ROWE questionnaire on the one hand, and the same overall score of the WOSI questionnaire and the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire scores.

The hypothesis was that the WOSI scores would correlate more closely with the ROWE questionnaire than with the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. Results showed that there was a Pearson correlation of 0.745 with the ROWE questionnaire and a 0.474 correlation with the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, confirming the initial hypothesis (Figs. 3 and 4).

Sensitivity to changeThis refers to the measurement which reliably detects and quantifies variations of a trait in a dimension or construct, however small they may be. This is an important characteristic to consider in the tools for measuring health since it offers us an indication of the degree to which measurements discriminate between groups possessing different amounts of one attribute or characteristic (⿿sensitivity⿿), or between the changes in this attribute, characteristic or variable which have taken place (⿿responsiveness⿿). The weighting of the changes was performed using:

- 1.

Analytical approximation to the concept of sensitivity to change: this is shown in the descriptive presentation of the following box diagramme (Fig. 5) and the presentation of results obtained inferentially through different calculations made using Student's t-test.

- 2.

Student's t-test: the result obtained was that the average of differences was 42.38 points, with confidence intervals (CI 95) ranging from 34.56 to 50.21 points with a P value of .000 (Table 5).

Table 5.Results (Student's t-test, standardised mean response, effect size) of the Spanish version WOSI questionnaire.

WOSI Student's t-test Limits of the 95% confidence interval Standardised response mean (SRM) Effect size

(ES)Physical examination 33.01 23.71 42.31 1.98 1.96 Sports/recreation/work 56.79 46.05 67.53 2.20 2.57 Lifestyle 38.87 26.60 51.15 1.57 1.76 Emotional well-being 59.50 46.99 72.02 2.36 3.99 Total 42.38 34.56 50.21 2.69 2.61 ES: effect size; SRM: standardised response mean.

- 3.

Effect size (ES): this is the result between the mean change which has occurred and the standard deviation of the initial measurement obtained, which was 2.61 (Table 5).

- 4.

Standardised response mean (SRM): this is the ratio of the differences between the previous and subsequent averages divided by the standard deviation of the differences. The result obtained was 2.69 (Table 5).

- 5.

Standard error measurement (SEM): this is the standard deviation of measurement errors associated with scores observed from a test, for a particular sample group tested. The result obtained was 23% (Table 6).

Table 6.Comparative results of the transcultural adaptation of the WOSI questionnaire into different languages and the original.

Kirkley/Gryphon Swedish German Italian French Japanese Dutch Spanish α 0.96.

ICC 0.949α 0.95.

ICC 0.89α 0.89.

ICC 0.87α 0.95.

ICC 0.93α 0.85.

ICC 0.84α 0.84.

ICC 0.91α 0.96.

ICC 0.92α 0.96.

ICC 0.94SRM

0.931N=22

SRM

1.40

ES

1.67NA

NAN=39

SRM

1.94

ES

1.47NA

NANA

NAN=39

SRM 1.94N=20

SRM 2.69

ES 2.61α: Cronbach alpha; EF: effect size; ICC: interclass coefficient correlation; SRM: standardised response mean.

- 6.

Minimum detectable change (MDC): this represents the minimum amount or lower limit which a score must show, and it reflects a real clinical change rather than a change caused by a measurement error. The result was 76% (Table 6).

From a statistical viewpoint this study is analogous to that of Salomonson et al.8 who were the first to adapt the WOSI questionnaire. The highest percentage of variability was observed in the group distribution they made. They used the EQ-5D-5L14 questionnaire which is a widely used and contrasted quality of life questionnaire, generic and standardised in tone, and is the basis of the national health survey created by the Spanish Government's Ministry of Health.

One of the specific quality of life questionnaires most frequently used in shoulder pathology for the study and follow-up of patients with glenohumeral instability is the ROWE15 questionnaire, which is also used in practically all adaptation and validation studies into other languages of the WOSI questionnaire, with the limitation that its different adaptations have not been validated. In fact, up until our study we have no record of whether any specific questionnaire exists in the Spanish language for the assessment of patients with shoulder instability with the appropriate psychometric validation, since the Constant24 (partial validation) and the DASH25 questionnaires (with validation) are not very specific for this pathology.

Mention should be made of the questionnaire translation and cultural adaptation process, since only correct methodology of the same ensures a result which is conceptually equivalent to the original and reproducible in other adaptations. This detail is often omitted in other works. Assessment of the back-translation by the author/s of the original questionnaire may help to give conceptual meaning to several items, as occurred in our case.

The pilot test was an indication of the how well the patients understood the questionnaire adaptation. We believe it is necessary that patients have to hand a documented clarification of the items, particularly if they are completing a self-administered questionnaire, either on-site or by post8 and/or through a web site.13

Structural validity was weighted using a factorial confirmatory analysis in order to verify the validity of the 4 dominions⿿ structure analogously to the validation made in Dutch13 and these were the only two validations to date made by this analysis. Factorial analysis shows us that the original structure of 4 dominions did not obtain the best results, although it works appropriately after rotation and functions better than the three dominion model. The factorial structure that works best is that corresponding to one dominion (Table 2) with values above 0.50 in all items (as results are considered significant when the said value is found to be above 0.30⿿0.40). We believe that this derives from the lack of distinction of some questions such as ⿿the need to protect your arm⿿ or ⿿fear of falling⿿ which form part of the sports activities and lifestyle section, respectively, and which could perfectly easily also fit the emotional aspects section. This could result in bias relating to saturation of the corresponding dimension.

After matrix rotation the 4 dimension or factor model results in saturation of items and certain correct associated commonalities which enables us to maintain it.

Our comparative results are located in the upper band of adaptation (Table 6). They are measured with the Cronbach alpha: 0.96 and ICC: 0.94 and are practically identical to the results of the original questionnaire (Tables 3 and 4). This proves that no changes were made during the cultural adaptation process of the questionnaire that undermine its properties compared to the original questionnaire (Table 6).

Groups 2 and 3 (only those patients who underwent surgery in the latter group) were ⿿used⿿ for criteria validity analysis, and they were correlated with:

-

The ROWE questionnaire for convergent validity, where they presented a Pearson correlation of 0.745 and a proportion of explained variance which oscillated between 54.9% and 55.7%. From this analysis we were able to conclude that, in keeping with statements by Salter et al., eligibility and psychometric sufficiency are excellent.

-

A Pearson correlation of 0.471 arose for divergent validity with the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. As was foreseen, this correlation has less statistical power than that obtained by the Rowe questionnaire, given that the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire is a non-specific quality of life questionnaire.

Sensitivity to change was weighted using the Student's t-test; SRM; ES; SEM; MDC. Proportional results are shown in Table 6. The 20 patients assessed after surgery indicated a substantial change in scoring on the WOSI questionnaire and this was confirmed by:

-

The Student's t-test statistic: the statistical hypothesis test proving the hypothesis of an absence of change in mean response of a measurement between two times. Since this is a design with repeated measurements of the same subject, the t is used for related data (Table 5). In our case the average difference was high, with a score of 42.38 points (95% confidence limits 34.56 to 50.21, P: .000) reflecting a major difference between the measurement averages before and after surgical treatment.

-

ES: statistically this is a measure of the strength of a phenomenon (for example, the change in result after an experimental intervention). It is a way of quantifying the effectiveness of a particular intervention, relating to a comparison. Our result was 2.61 (in the Salter classification an excellent result starts at 0.80).

-

SRM: this is the ratio between the mean change which has occurred and the standard deviation of this change. It is independent of sample size and change variability is taken into consideration. It is believed to be the most appropriate statistic for the study of sensitivity in this type of design. The result obtained was 2.69, which is also greater than that obtained by Kirkley and Gryphon in the original questionnaire. One of the advantages of having highly sensitive questionnaires is that moderate changes in patients may be observed and they facilitate the need for a lower N to demonstrate statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.8

-

SEM: when it is used to calculate confidence intervals for the scores obtained it may help to express the uncertainty of individual scores in an easily comprehensible manner. In our study this was 23%, which would indicate a more than acceptable amount of error for working with any applicable confidence level.

-

MDC: proves that a statistically significant difference between two periods does not necessarily indicate that a significant clinical change has occurred or that this is not about a measurement error. In our study a high percentage of patients surpassed the MDC (76%) (MDC%) indicating that the questionnaire is able to detect any clinical change occurring as a consequence of treatment.

-

The floor and ceiling effect occurs when over 15% of patients achieve the lowest or highest possible score prior to surgical intervention, so that it would be impossible to measure the degree to which they subsequently improve or deteriorate. Although no floor or ceiling effect arose in our study, as was expected scores were very high in Group 1 (the benchmark). The fact that the score value is not 100% for all individuals with healthy shoulders supports the idea that scoring may also be sensitive to patients with moderate symptoms and there are also questions which are not ⿿solely⿿ related to shoulder instability but which deal with symptoms such as stiffness and neck muscle pains, etc.

To conclude, our work endorses the Spanish version of the WOSI questionnaire which combines validity, accuracy and sensitivity to change with optimum values. Its administration is versatile and we therefore recommend its use in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with shoulder instability.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence I.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed adhere to the ethical guidelines of the Committee responsible for human experimentation and with the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding patient data publication.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent from the patients and/or individuals referred to in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Mr. J. Rincón, scientific consultant, for his collaboration in this study development. Also Mrs. Silva Torosian and Mr. S. Castellvi, specialists in English grammar, and to Mr. J.C. Oliva and Mr J. Ortiz, specialists in mathetmatics and statistics.

Please cite this article as: Yuguero M, Huguet J, Griffin S, Sirvent E, Marcano F, Balaguer M, et al. Adaptación transcultural, validación y valoración de las propiedades psicométricas, de la versión española del cuestionario Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:335⿿345.