Rachis deformities are very common in patients suffering from neuromuscular diseases (25–80%), particularly in those with limited mobility.1 Neuromuscular scoliosis usually presents early in life, does not respond to orthopaedic treatment and the patient is referred for surgery when there is 35–60° depending on aetiology (in a Duchenne type muscular dystrophy the patient is referred for surgery from 35° to 45° when there is no ambulation, whereas in type II spinal atrophy or infantile cerebral palsy in many cases surgery is postponed until 60°).2

The complication rates associated with surgical treatment are very high (18%) compared with other types of scoliosis (idiopathic scoliosis: 1%). Complications are inherent with the comorbidities associated with this type of patient: loosening of material secondary to osteoporosis, respiratory failure due to muscular weakness, malnutrition and repetitive urinary infections, particularly in patients with myelomeningocele.1–4 Respiratory complications are by far the most frequent (2.7%), whilst complications related to mobility or implant migration are less common (1.27–13.3%).3

We present an unusual complication related to implant migration.

Clinical caseWe present the case of a male patient aged 32, who could not walk, as a result of neuromuscular scoliosis secondary to myelomeningocele, and who had undergone a two-stage surgical procedure at 13 years of age with Luque-Galveston type instrumentation. The patient's medical history showed that he had a ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to hydrocephalus and had been operated on multiple occasions for left femoroacetabular dislocation. The patient also had a history of repetitive urinary infections attributed to the presence of vesicoreteral reflux and for which he was monitored in the urology department of our centre.

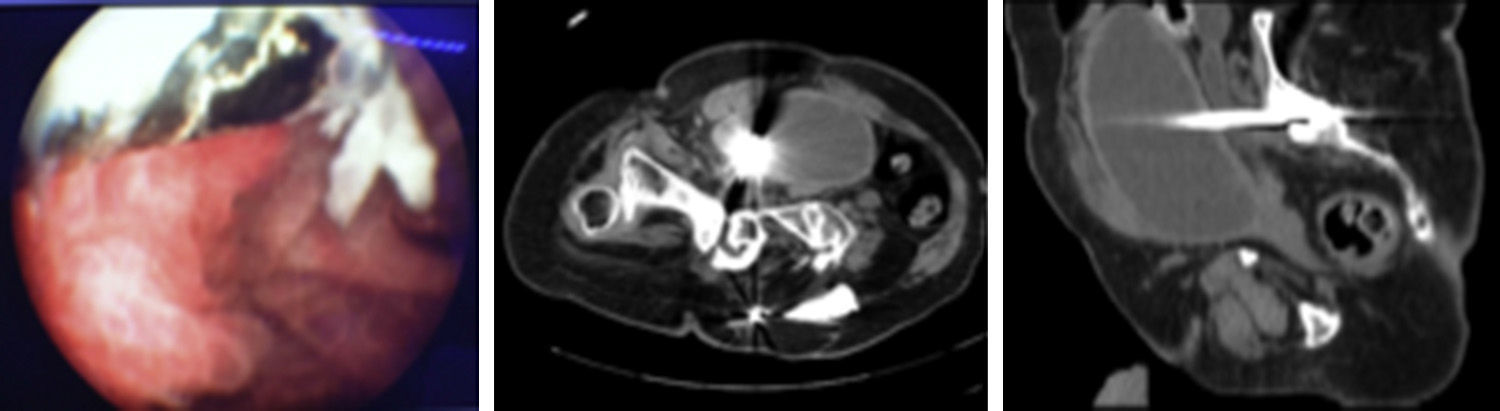

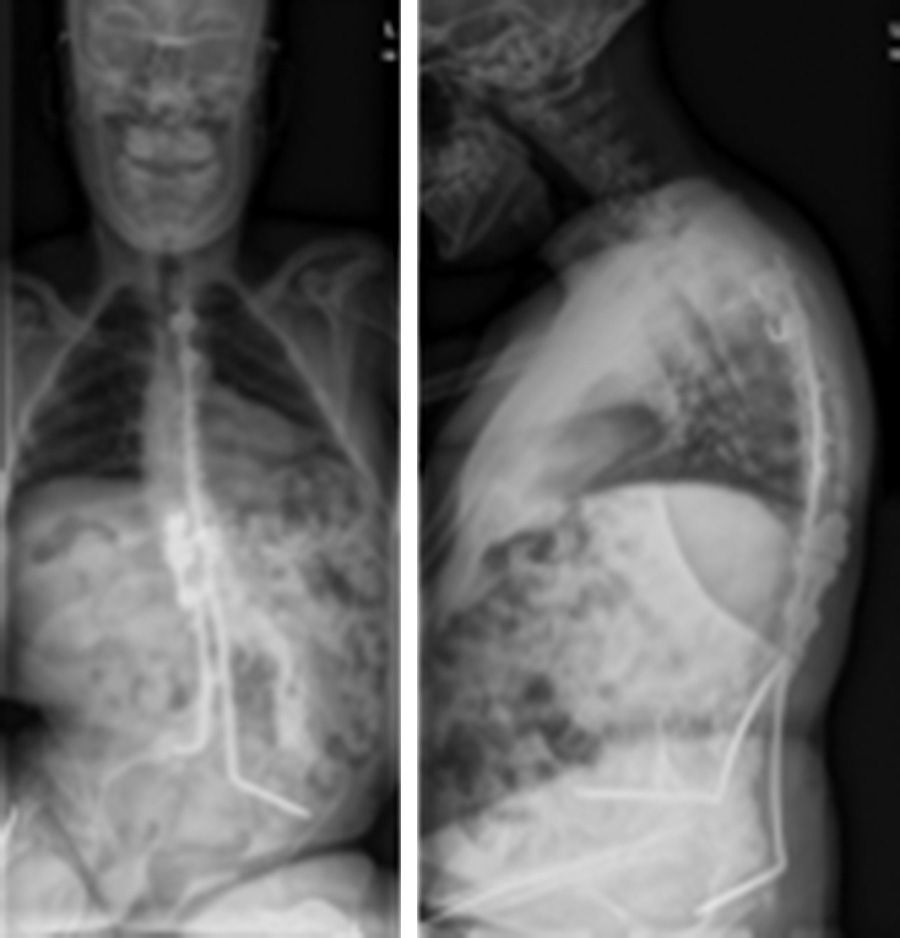

Current disease and diagnostic studyThe patient presented at the surgery due to the three-year old presence of intermittent leakage associated with a granuloma of <0.5cm at paravertebral level on the lower part of the surgical scar. A culture of the fistula was done which tested positive for Escherichia coli and removal of the implant was therefore recommended. The patient was concomitantly under examination due to repetitive MRSA urinary infections and the urology department therefore carried out a cystoscopy which showed the presence of a foreign metallic body at intravesical level (Fig. 1); a biochemical study was therefore performed on the leakage from the lumbar wound which tested positive for urine. Plain radiography (Fig. 2) showed a displacement of the left iliac anchorage screw, confirmed by a CAT scan (Fig. 1), which substantiated the intravesical location of the displaced implant.

Two-stage surgery was performed: (1) pre-operative cystoscopy confirmed the presence of the metallic material; (2) removal of the implant by posterior route; (3) post-operative cystoscopy which verified the disappearance of the foreign body and damage to the bladder wall <1cm which was treated with 3 months permanent urinary catheterisation.

Complications: during post-operative cystoscopy the patient suffered from a cardio respiratory arrest when standing up from a supine position due to massive PTE; heartbeat was recovered with no sequelae following PCR and urokinase.

ResultsThe intra operative cultures tested positive for MRSA which resulted in anti-biotic treatment for 6 months with a good clinical and analytical evolution. After 1.5 years the patient had had no recurrence of the fistula and the frequency of his urinary infections was reduced. As a result of the PTE he required anticoagulant treatment for 9 months, and there were no further symptoms. Radiologically no progression of the scoliosis was present two years after the surgical removal of the implant.

DiscussionThe incidence of scoliosis in patients with myelomeningocele is extremely high (82.5% by the age of 10).5 The progression of this scoliosis is one of the major problems in children with myelomeningocele and in the majority of cases some type of surgical intervention is required.

Surgery in patients with neuromuscular scoliosis has been associated with a high rate of complications. The SRS reported a complication rate of up to 17.9% in neuromuscular scoliosis, followed by 10.6% in congenital scoliosis, and a 6.3% in idiopathic scoliosis; mortality rates are similar in pattern at 0.34% in neuromuscular scoliosis and 0.02% in idiopathic scoliosis.6

Complications related to surgery are divided into different types: medical, neurological, infectious and those relating to implant and pseudarthrosis. The complication rate relating to implants is variable in literature (0–66.7%). A recent meta-analysis estimated that this incidence is around 12.51% (465/7612 NMS). These complications are divided into maladjustment of the implants leading to perforation or penetration (PR 4.81%), review of implants due to infections or skin irritation (PR 7.87%), rupture of implants (PR 4.6%) and their migration (PR 2.38%).3

In a selected sample of patients with myelomeningocele, Greiger et al. described a higher rate of complications relating to implants (52.9%). In this study 29.8% of complications were related to the implant with the most frequent being in patients who underwent surgery after they were 14 years old (40% vs. 21%). The authors describe 5% of implant rupture with a flow migration of the rod in 2 of the cases (2/4) and 22% migration with these complications being more frequent in the instrumentations with Harrington rods (75%) than patients instrumented with CD system rods (28–30.8%).7

Nectoux et al. reported a complication rate of 56.2% related to implants in patients with cerebral palsy who were operated on with the Luque-Galveston technique: 7 ruptures of the sublaminar wiring at T2–T7 level, one iliac bone perforation, one cutaneous irritation and 3 sacral ulcers.1 We were however unable to find articles in the literature referring to visceral perforation as a consequence of implant mobilisation in patients who underwent surgery for scoliosis like that case presented in this article.

Bladder injuries are uncommon and are usually associated with high energy trauma. Penetration injuries are less frequent and their most common aetiology is iatrogenic (the most common).8,9 The majority occur intra-operatively during: urological surgery (0.4/1000), gynaecological surgery (1.5/1000–3/1000) or abdominal surgery (1.6/1000).9 Some anecdotal reports exist regarding injuries secondary to implant erosion (catheters, gynaecological implants,9 artificial hips).

Bladder injuries are classified into different types depending on the type of injury, location (intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal) and its size (above or below 2cm).8 In our case the extraperitoneal injury was below 2cm.

Treatment of extraperitoneal bladder injuries focuses on the insertion of an indwelling urinary catheter.8 The majority of these injuries are resolved with this treatment within a period of 10–21 days.9 However, several authors have published a complication rate of 26% with this treatment including: vesico-cutaneous fistula (3%), no wound healing (15%) and one case of sepsis which led to the patient's death.10 in the case of iatrogenic injuries, the authors recommend immediate repair if the injury is detected intra operatively. If the injury is not noticed or in injuries with late diagnosis, treatment must be defined by each individual case, depending on the type of injury, time of evolution and medical condition of the patient.9 In our case, the injury was resolved without complications with the insertion of a permanent urinary catheter for 3 months.

Although visceral complications by perforation are infrequent in orthopaedic surgery and the cases published in the literature have been linked to prosthetic hip surgery, it is important to bear in mind that surgery for scoliosis, and particularly when a migration of pelvic anchorage elements have led to complications from delayed diagnosis may have a serious outcome. Exhaustive preoperative studies are essential in the light of an event that may easily go unnoticed.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animals subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were carried out on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have adhered to the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Please cite this article as: Rieiro G, Matamalas A, García-de Frutos A. Fístula vésico-lumbar por migración de la instrumentación posterior. Complicación a largo plazo en la escoliosis neuromuscular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:394–396.