Emotion dysregulation has been consistently linked to psychopathology, and the relationship between disability and depressive symptomatology in old age is well-known.

ObjectiveTo examine the mediational role of emotional dysregulation in the relationship between perceived disability and depressive symptomatology in older adults.

MethodsTwo hundred eighty-three participants, aged 60–96 years (M±SD=74.22±8.69; 62.9% women; 29.0% with long-term care support [LTC-S] and 71.0% community residents without LTC-S), were assessed with the Geriatric Depression Scale-8 (GDS-8), the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-2 (WHODAS-2), and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 (DERS-16).

ResultsA mediation model was established, which revealed: (1) a moderate association between WHODAS-2 and GDS-8 (β=0.20; p<.001); (2) DERS-16 partially and weakly mediated the relationship between WHODAS-2 and GDS-8 (β=0.003; p<.01). The model explained 31.9% of the variance of depressive symptoms. An inconsistent mediation model was obtained in the LTC-S group.

ConclusionsGlobally, our findings indicate that disability has an indirect relationship with depressive symptomatology through emotional dysregulation (except for those in the LTC-S). Accordingly, we present suggestions for the treatment of depressive symptoms and for the inclusion of other emotion regulation variables in the study of the disability-depressive symptom link in future studies with older people in the LTC-S.

La desregulación de las emociones se ha relacionado sistemáticamente con la psicopatología, y es bien conocida la relación entre la discapacidad y la sintomatología depresiva en la edad avanzada.

ObjetivoExaminar el papel mediador de la desregulación emocional en la relación entre la discapacidad percibida y la sintomatología depresiva en los adultos mayores.

Materiales y métodosDoscientos ochenta y tres participantes, entre 60-96 años de edad (M±DE=74,22±8,69; 62,9% mujeres; 29% con apoyo de cuidados de larga duración [A-CLD] y 71% residentes en la comunidad sin A-CLD), fueron evaluados con la Geriatric Depression Scale-8 (GDS-8), el World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-2 (WHODAS-2) y la Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 (DERS-16).

ResultadosSe estableció un modelo de mediación que reveló: (1) una asociación moderada entre el WHODAS-2 y el GDS-8 (β=0,20; p<0,001); (2) el DERS-16 medió parcial y ligeramente la relación entre el WHODAS-2 y el GDS-8 (β=0,003; p<0,01). El modelo explicó el 31,9% de la varianza de los síntomas depresivos. Se ha obtenido un modelo de mediación inconsistente en el grupo A-CLD.

ConclusionesGlobalmente, nuestros hallazgos indican que la discapacidad tiene una relación indirecta con la sintomatología depresiva a través de la desregulación emocional. En consecuencia, presentamos sugerencias para el tratamiento de los síntomas depresivos y para la inclusión de otras variables de regulación de las emociones en el estudio del vínculo discapacidad-síntomas depresivos en futuros estudios con personas mayores en el A-CLD.

Depression and depressive symptoms are major public health problems among older adults (e.g.,1,2), for which the loss of autonomy, independence, and functional capacity could be contributing factors.3 Functional impairment and disability are critical health-related problems in older people, and their relationship with depression is well recognized (e.g.,4). Older people, limited by functional impairment and disability, tend to experience dependence, reduced social contacts, and greater social isolation, creating the conditions for depressive symptoms.4–6

Disability has many conceptual and operational definitions, but the umbrella conceptualization from the World Health Organization based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) is the most accepted. It includes impairments from disease and injury, physical and mental functional problems resulting from the impairments, and participation constraints related to unsupportive environments.7

Various other factors also influence the development of depressive symptoms and depression. Many studies addressed the role of age in depression in older people (e.g.,8), with a review discovering no significant increased propensity to depression with increasing age.9 The link with advancing age found in some studies (e.g.,10) may be explained by aspects linked to aging, such as a higher proportion of women in this group, more incapacity, worse cognitive functioning,11 and institutionalization.8 Extensive literature has shown that depressive symptomatology and depression prevalence in older adults differs between men and women (e.g.,9,12). Other factors have been associated with depressive symptomatology and depression in old age, including low education or no formal education12,13; being unmarried12; and being supported in long-term care,2,13 where dependency is usually higher.14

To the best of our knowledge, no research has been conducted to identify mechanisms of the relationship between disability and depressive symptoms in older adults. One possible mechanism of depression and depressive symptoms is emotion regulation.15 Emotion regulation strategies involve several skills that influence the type of emotional response (e.g., awareness and understanding of emotions; acceptance of negative emotions,16 problem-solving, reappraisal17). Conversely, emotion dysregulation includes maladaptive strategies associated with greater psychological difficulties (e.g., avoidance, rumination, and suppression,17 nonacceptance of emotional responses, and lack of emotional awareness16). Some studies reveal that, with increasing age, there is a tendency for better emotion regulation18 and a diminution in maladaptive strategies (e.g.,15,18). Despite its decrease with age, emotion dysregulation has been growingly studied in older people, among whom it was shown an association with depression symptoms.15,17 A meta-analysis showed that maladaptive strategies associate more strongly with psychopathology than adaptive ones, with the relationship being more robust in mood-related disorders than other problems.19 Therefore, in this paper, we concentrate on emotion dysregulation. Besides age, other factors play a role in emotional dysregulation, such as sex (women are more likely to use several and different emotion strategies than men15) and schooling (education attainment protects against emotional dysregulation20).

In synthesis, the relationship between the level of disability and depressive symptoms may be mediated by emotional dysregulation. Functional impairment and limitations can be assumed to increase emotion dysregulation,21 and, in turn, emotion dysregulation can predict depression.22 Therefore, identifying specific mechanisms for the association between disability and depressive symptoms may provide a theoretical model to explain the relationships between these variables. Such a mediational model can help understand how these constructs are related, which is vital to act preventively and develop tailored interventions to address depressive symptomatology. Thus, in the present study, we intend to verify whether emotional dysregulation was a significant mediator between the level of disability due to health conditions including diseases, illnesses, or injuries, mental or emotional problems, and depressive symptomatology in older adults. According to the evidence reviewed, we hypothesized that emotional dysregulation significantly mediated the relationship between perceived disability due to health conditions and depressive symptoms. We assumed conditional relationships between disability, emotional dysregulation, and depressive symptoms as per age, sex, marital status, having vs. not-having long-term care support (LTC-S), and years of education.

MethodsGeneral scopeThis study is part of the research project “Aging trajectories” (PTDC/PSI-PCL/117379/2010). In this project, we assess the cognitive, mental, and physical health of older people in Portugal's central region. The Ethics Committee of Miguel Torga Institute of Higher Education approved the project (CE-P11-18).

ParticipantsThe study's inclusion criteria were: (1) age 60 years or older; (2) ability to understand the assessment instructions and willingness to provide written informed consent; and (3) sufficient cognitive capacity. The exclusion criteria were: severe neurocognitive disease, severe cognitive or severe physical impairment (e.g., bedridden), severe organic disorders, or alcohol abuse. Severe cognitive impairment (cognitive functioning below normal for schooling, without meeting the criteria for dementia) was based on the cutoff points established for the MMSE (0–2 years of education: 22; 3–6 years: 24; and ≥7 years, 2723).

Eighteen people (5.2%) refused to participate, and we removed 43 (12.5%) from the analyses due to severe cognitive impairment. Moreover, within LTC-S, we did not assess 73 participants (17.3%) for being bedridden with a physical illness or unable to partake due to severe neurocognitive disease (e.g., dementia, stroke). Two hundred and sixty-seven additional people (63.3%) were not assessed due to logistical constraints and institutional closure due to the COVID pandemic.

Thus, a total of 283 individuals accepted to participate. Table 1 presents their main sociodemographic characteristics. Age varied between 60 and 96 years (M±SD=74.22±8.69). The majority of the respondents were female (n=178; 62.9%), had more than 4 years of formal education (M±SD=5.10±3.81), and were married (n=156; 55.1%). The sample included 82 (29.0%) having LTC-S and 201 (71.0%) from the community without LTC-S, mainly residing in the Center Region of Portugal mainland (97.5%), with the remaining living in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Groups | N | % | Statistical test and significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | χ(1)2=2.58;p=.108 | ||

| ≤74 years | 155 | 54.8 | |

| ≥75 years | 128 | 45.2 | |

| Sex | χ(1)2=18.83;p<.001 | ||

| Male | 105 | 37.1 | |

| Female | 178 | 62.9 | |

| Education | χ(1)2=62.51;p<.001 | ||

| 0–3 years | 75 | 26.5 | |

| ≥4 years | 208 | 73.5 | |

| Marital status | χ(1)2=2.97;p=.085 | ||

| Unmarried | 127 | 44.9 | |

| Married | 156 | 55.1 | |

| Long term care support | χ(1)2=50.04;p<.001 | ||

| No | 201 | 71.0 | |

| Yes | 82 | 29.0 | |

Note. N=283. χ2=goodness of fit chi-square.

Long-term care users were recruited from nursing homes (42.7%), day-care centers (39.0%), and home care provided by these institutions (18.3%). Home care users were included in the LTC-S group, considering that previous studies showed no statistically significant differences regarding the variables under study (e.g.,2,24,25). The community residents without LTC-S were enrolled through snowball sampling and geographical convenience: researchers’ families and acquaintances asked their friends and relatives to partake. All participated without compensation.

ProceduresAuthorization was requested from institutions, when justified, and from authors of the instruments. Criteria for including participants having LTC-S were ascertained by inspecting the individual medical records and supported by resident psychologists. In the community recruitment, inclusion criteria were assured by the researchers’ assessment.

Trained psychologists evaluated the volunteer participants with 16 instruments (9 questionnaires alternated with 7 neuropsychological tests), including the four questionnaires described in this study, taking about 2h. The assessment was scheduled in one session with a break after eight instruments. However, another day for the remaining assessment was used if the older person preferred instead of a break. Informed consent and the assessment questionnaires were read to all subjects during one or two sessions.

InstrumentsSociodemographic questionnaireThe questionnaire consisted of 16 questions, including age, sex, education, marital status, and housing. Education levels were recategorized into two groups (0–3 years) and (≥4 years), as few participants had secondary education and post-secondary/tertiary education.

Geriatric Depression Scale-8The GDS-813 ascertains the existence of depressive symptoms and their severity, with eight items answered in a dichotomous manner (“yes” or “no”) regarding the last week. The score ranges from zero to eight (cutoff>6 suggestive of major depression). As for reliability, Cronbach's alpha was .87 in this study.

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-2The WHODAS-26 is based on the ICF and assesses the functioning and disability related to self-perceived health conditions regarding the last 30 days. The 12-item version assesses six components: mobility, self-care, daily activities, cognition, participation, and interpersonal relationships. The underlying factor is a general disability factor. Answers are given on a scale ranging from zero to four, with the total varying between 0 (less disabled) and 48 (more dependent). Scores between 10 and 48 indicate probable clinically significant disability.6 WHODAS-2 presented a Cronbach's alpha of .93 in the present study.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16The DERS-1626 consists of five subscales that evaluate significant difficulties in emotion regulation; however, we only used the total score. The DERS-16 is answered on a Likert scale (1–5) varying from 16 to 80 (more difficulties). In this study, the DERS-16 full scale showed high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.96).

Statistical analysisStatistical calculations were performed using the JASP software (version 0.14.1).

Power analysisA pre-analysis of statistical power with G*Power software (https://bit.ly/3FZArXO, accessed January 25, 2022) showed that the adequate sample size should be over 102 to detect medium effects (d=0.50; r=0.30) to get a power >.80, with alpha=.05 for the respective statistical tests (t-test, and correlation). We assumed the effect of WHODAS-2 on DERS-16 would be of medium size, and the effect of DERS-16 on GDS-8 would be large. Thus, using G*Power with the linear multiple regression module, a sample size between 33 and 74 was required for .95 power with seven ‘predictors’ (predictor, mediator, and covariates).

Descriptive, comparisons, and correlationsCategorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were conveyed as means±standard deviation. Student's t-test and Cohen's d effect size, Pearson chi-square test, and phi measure (φ) were used to compare the GDS-8 scores between categories of sociodemographic factors. ANOVA and post hoc Bonferroni-corrected t-tests were used to compare the scores of study variables according to the type of LTC-S plus the community setting without LTC-S. Pearson's correlations tested GDS's relationship with age, WHODAS-2, and DERS-16. The determination coefficient (R2=r2×100) was calculated to determine the relationships’ magnitude.

Group differencesThe number of participants did not differ by age group (χ(1)2=2.58;p=.108) or marital status (χ(1)2=2.97;p=.085). There were statistically significant differences regarding the variables sex (χ(1)2=18.83;p<.001), education (χ(1)2=62.51;p<.001) and having vs. not-having LTC-S (χ(1)2=50.04;p<.001), as detailed in Table 1.

MediationWe performed mediation analysis to study whether the relationship between WHODAS-2 and GDS-8 was mediated by DERS-16, i.e., a mediation model was used to test whether there was a significant indirect effect between WHODAS-2 and GDS-8 through DERS-16. Sociodemographic factors were entered as covariates to the mediational model. Estimates were computed with bias-corrected bootstrapping (n=5000) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We considered the 95% confidence intervals for the coefficients calculated by bootstrapping methods statistically significant if the confidence intervals did not include zero. Variance accounted for (VAF)27 GDS-8 was calculated. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and significance was determined at the .05 level.

ResultsDescriptive analysis of GDS-8, WHODAS-2, and DERS-16Descriptives are presented in Table 2. In addition, it should be noticed that 38.5% (n=109) were above the cutoff point suggestive of a depressive state, and 60.0% (n=174) had probable clinically significant disability.

Descriptives statistics and Pearson's correlations between study variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. GDS-8 | 3.53 | 2.83 | – | ||

| 2. WHODAS-2 | 21.87 | 21.22 | 0.31*** | – | |

| 3. DERS-16 | 32.78 | 15.56 | 0.42*** | 0.16*** | – |

Note. N=283. DERS-16: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; GDS-8: Geriatric Depression Scale; WHODAS-2: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

Individual differences in the study variables are presented in Table 3. Adding to Table 3, GDS-8 correlated weakly but significantly with age (r=.21; p<.001; 95% CI .09–0.32; R2=4.2%). The prevalence of depressive symptoms was lower in the 60–74 years (43.1%) than the >75 years age group (56.9%) in a statistically significant way (χ2=9.72; p<.01; φ=.19).

Group descriptives and group differences, with effect sizes.

| Variables | Groups | M | SD | t | p | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| GDS-8 | ≤74 years | 2.97 | 2.71 | 3.70 | <.001 | 0.44 |

| ≥75 years | 4.20 | 2.83 | ||||

| WHODAS-2 | ≤74 years | 14.77 | 16.29 | 6.13 | <.001 | 0.73 |

| ≥75 years | 29.07 | 22.85 | ||||

| DERS-16 | ≤74 years | 31.97 | 15.51 | 0.97 | 0.332 | 0.12 |

| ≥75 years | 33.77 | 15.49 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| GDS-8 | Male | 2.40 | 2.54 | 5.40 | <.001 | 0.66 |

| Female | 4.19 | 2.78 | ||||

| WHODAS-2 | Male | 14.96 | 18.36 | 4.01 | <.001 | 0.49 |

| Female | 24.94 | 21.25 | ||||

| DERS-16 | Male | 28.40 | 13.55 | 3.74 | <.001 | 0.46 |

| Female | 35.37 | 16.03 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| GDS-8 | 0–3 years | 4.20 | 2.75 | 2.43 | 0.016 | 0.33 |

| ≥4 years | 3.28 | 2.82 | ||||

| WHODAS-2 | 0–3 years | 33.19 | 21.43 | 6.19 | <.001 | 0.83 |

| ≥4 years | 16.93 | 18.77 | ||||

| DERS-16 | 0–3 years | 36.15 | 15.85 | 2.21 | 0.028 | 0.30 |

| ≥4 years | 31.57 | 15.23 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| GDS-8 | Unmarried | 4.21 | 2.85 | 3.77 | <.001 | 0.45 |

| Married | 2.97 | 2.69 | ||||

| WHODAS-2 | Unmarried | 24.52 | 21.91 | 2.43 | .016 | 0.29 |

| Married | 18.56 | 19.44 | ||||

| DERS-16 | Unmarried | 33.90 | 16.02 | 1.09 | 0.275 | 0.13 |

| Married | 31.87 | 15.06 | ||||

| Long term care support | ||||||

| GDS-8 | No | 3.44 | 2.88 | 0.78 | 0.436 | 0.10 |

| Yes | 3.73 | 2.71 | ||||

| WHODAS-2 | No | 16.52 | 17.33 | 6.39 | <.001 | 0.84 |

| Yes | 32.80 | 23.84 | ||||

| DERS-16 | No | 32.44 | 15.74 | 0.58 | 0.561 | 0.08 |

| Yes | 33.62 | 14.97 | ||||

Note. N=283. DERS-16: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; GDS-8: Geriatric Depression Scale; WHODAS-2: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

In support of the argument for including older people in-home care in the LTC-S user group, there were no statistically significant differences between home care users vs. nursing home residents (GDS: t=0.27, pbonf=1.00; WHODAS-2: t=1.45, pbonf=.888; DERS-16: t=1.79, pbonf=0.447) and home care users vs. day-care center residents (GDS: t=0.30, pbonf=1.00; WHODAS-2: t=1.47, pbonf=.852; DERS-16: t=2.07, pbonf=0.234). Additionally, it should be noted that older community people without LTC-S presented similar levels in GDS, WHODAS-2, and DERS-16 compared to the other three groups (pbonf=1.00).

Correlations between GDS-8, WHODAS-2, and DERS-16Table 2 shows that the GDS-8 correlated positively and moderately with WHODAS-2 (R2=9.6%) and weakly with DERS-16 (R2=2.7%). It should be noted that the correlation between the predictor (WHODAS-2) and the mediator (DERS-16) reduced the effective sample size to 256; however, power (>.95) was not compromised.27

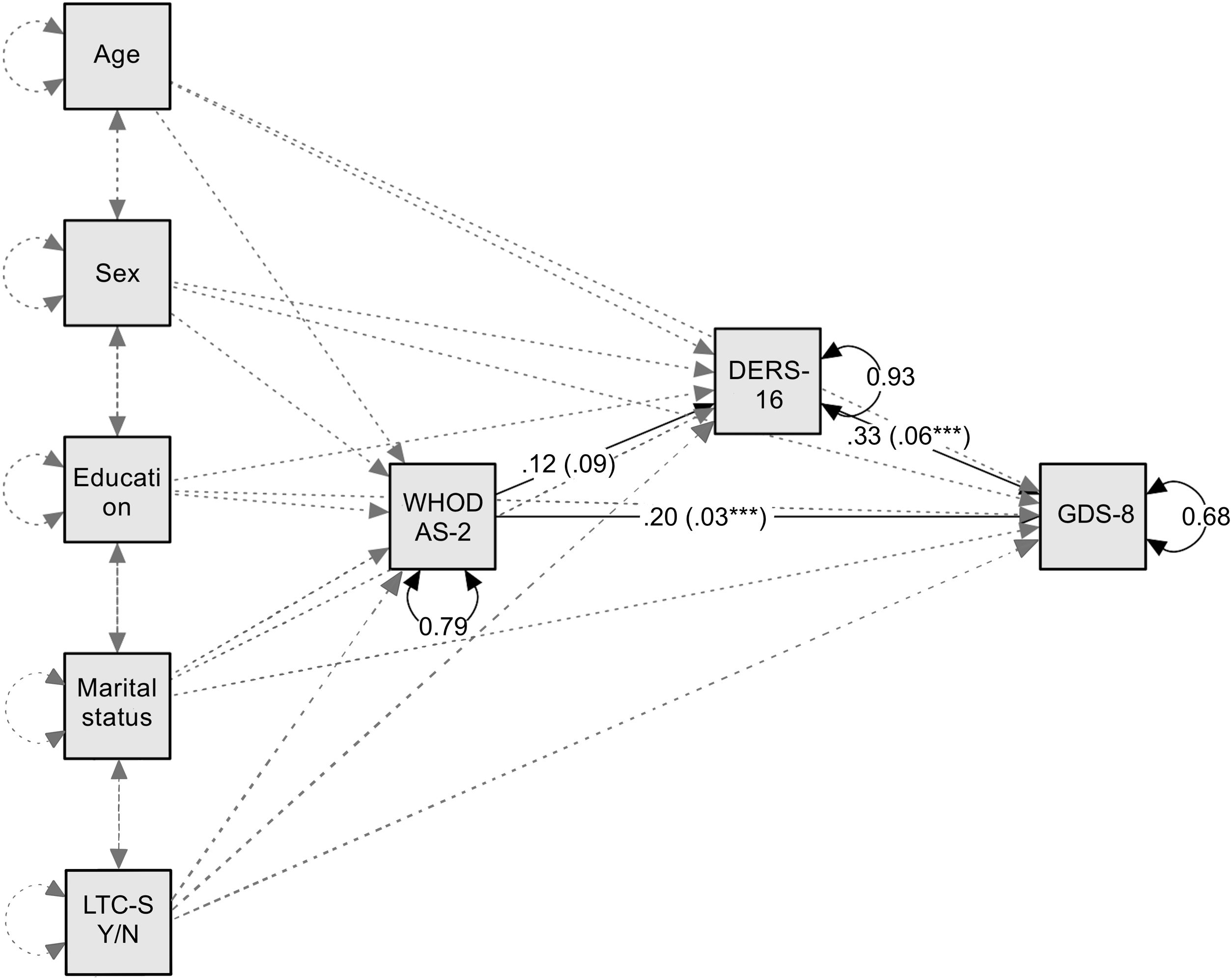

Mediation effect of DERS-16 in the relationship between WHODAS-2 and GDS-8The hypothesized mediational model (Table 4) was tested, weighing the effects of sociodemographic factors as covariates (age, sex [dummy coded], education, marital status [dummy coded], and having vs. not-having LTC-S [dummy coded]).

Mediating effect of emotional dysregulation in the relationship between perceived disability and depressive symptoms.

| Predictors | β | B | SE B | z | p | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age→GDS-8 | 0.13 | 0.723 | 0.330 | 2.19 | .028 | 0.076 | 1.369 |

| Sexa→GDS-8 | −0.14 | −0.798 | 0.308 | 2.59 | .010 | −1.402 | −0.194 |

| Education→GDS-8 | −0.10 | −0.072 | 0.039 | 1.83 | .067 | −0.149 | −0.005 |

| Marital statusb→GDS-8 | −0.16 | −0.927 | 0.304 | 3.05 | .002 | −1.523 | −0.331 |

| Long term care supportc→GDS-8 | −0.19 | −1.151 | 0.370 | 3.11 | .002 | −1.877 | −0.425 |

| WHODAS→DERS-16 | 0.12 | 0.089 | 0.048 | 1.84 | .065 | −0.006 | 0.183 |

| DERS-16→GDS-8 | 0.33 | 0.060 | 0.009 | 6.49 | <.001 | 0.042 | 0.078 |

| Direct effects: WHODAS-2→GDS-8 | 0.20 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 3.55 | <.001 | 0.012 | 0.042 |

| Indirect effects: WHODAS-2→DERS-16→GDS-8 | 0.04 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 1.77 | .076 | −0.0005 | 0.011 |

| Total effects: WHODAS-2→GDS-8 | 0.24 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 3.76 | <.001 | 0.016 | 0.048 |

| R2 | 31.9% | <.001 |

Note. N=283. Analysis computed with JASP software with 5.000 bootstrap samples. β: standardized regression coefficients; B: unstandardized regression coefficients. DERS-16: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; GDS-8: Geriatric Depression Scale; WHODAS-2: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

Weighing the effects of all covariates, the total effect of WHODAS-2 on GDS-8 was significant, explaining 21.7% of GDS-8 scores variance. We found no evidence of a direct effect of WHODAS-2 on DERS-16. WHODAS-2 directly influenced GDS-8, and the association of DERS-16 with GDS-8 also was different from zero (Fig. 1). The mediation effect of emotional dysregulation in the relationship between disability and depressive symptoms was weak (VAF=15.6%). The results from 5000 bootstrapping samples indicated that the indirect effect was not statistically significant, with the bootstrapping 95% CI including zero. The proportion of the total indirect effect of WHODAS-2 on GDS-8 estimated by DERS-16 was 31.9%.

A partial mediation model of the relationship between disability and depressive symptomatology.

Note. N=283. Standardized regression coefficients of the mediational model (solid lines; unstandardized coefficients are in parentheses). Dashed lines represent covariates paths. DERS-16: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-16 items; GDS-8: Geriatric Depression Scale-8 items; LTC-S Y/N: long term care support (yes/no); WHODAS-2: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

***p<.001.

Given the potential role of the sociodemographic variables on the degree to which the functionality predicted depressive symptoms through emotional dysregulation, we retested the model again in eight separate mediation analyses (education was not analyzed as the estimate was not statistically significant): young-olds vs. old-olds; female vs. male; unmarried vs. married; having vs. not-having LTC-S. The mediation role of DERS-16 took place in both having vs. not-having LTC-S groups (p<.01). The indirect effects of DERS-16 were different (Index=−0.021; BootLLCI=−0.038; BootULCI=−0.006) in the comparison between groups, being statistically significant only in the not-having LTC-S group (effect=0.020; BootSE=0.007; BootLLCI=0.009; BootULCI=0.036). The mediation was inconsistent in the LTC-S group due to WHODAS-16 predicting lower scores in DERS-16 (B=−.293; BootLLCI=−0.164; BootULCI=0.107) and higher levels of GDS-8 (B=.036; BootLLCI=0.013; BootULCI=0.059).

The mediation role of DERS-16 took place in all the other groups (p<.05), with no differences in the indirect effects between them. Thus, DERS-16 mediated the link between WHODAS-2–GDS-8 in young-olds and old-olds; female and male; unmarried and married; and not-having LTC-S.

DiscussionThe main purpose of this study was to clarify the mechanism of the relationship between disability and depressive symptomatology by concurrently examining the mediational role of emotional dysregulation. The results showed that the level of disability was closely correlated with depressive symptomatology. Furthermore, somewhat consistent with our hypothesis, the relationship between disability and depressive symptomatology was partially and weakly mediated by emotional dysregulation. This mediation effect of emotional dysregulation accounted for a significant portion of the relationship between independent (disability) and dependent (depressive symptoms) variables.

Sociodemographic factors could influence the relations between core variables of the mediation model. For this reason, the influence of age, sex, education, marital status, and having-not-having LTC-S was assessed.

Regarding the GDS-8, scores varied significantly with age, consistent with other studies showing that depressive symptoms become more prevalent with aging.8,10 An age-associated increase in depressive symptoms is further strengthened by longitudinal research findings in a population-based sample.28 One possible explanation for our result can be cognitive and physical decline that limits activity and interaction and decreasing personal control of own life and destiny.29 Another study revealed a decrease with age13; however, this study only included older adults in long-term care homes. Older women reported more depressive symptoms than men. These results align with the studies by Figueiredo-Duarte et al.13 and de Silva et al.8 Possible reasons include women being more subject to lower socioeconomic conditions, inferior access to social activities, and less emotional support.13 GDS-8 scores did not differ between having vs. not-having LTC-S, although, in a longitudinal study,28 it was found that institutionalization was associated with an increased risk of developing depression. One would expect that people in the community (without LTC-S) would have fewer depressive symptoms since it is known that the transition to LTC-S results from aspects that increase depressive symptoms in older people, such as exacerbation of chronic conditions, falls, and hospitalizations.25,30 A possible justification for the absence of difference in depressive symptoms levels could be the higher number of social contacts in institutions and home care due to the larger number of people (staff and/or other older residents). Now, belongingness feelings and the level of support that older people receive in both institution- and home-based support settings could reduce depressive symptoms levels.1,25 Our findings support the potential protective role of education and marriage in mood, as those with low or no formal education12,13 and unmarried have higher GDS-8 scores.12

Considering WHODAS-16, it was found that disability is higher in the oldest-olds, women, those with less education, unmarried (including widowers, the divorced, and the never married), and receiving LTC-S. These findings are consistent with other studies (e.g.,4,5). The higher levels of disability among older people receiving LTC-S is an obvious result, considering that older people receive LTC-S precisely because they are usually disabled, especially in terms of getting around and self-care.14 Sex differences in disability could reflect lower socioeconomic status, more chronic diseases, and more debilitating effects of diseases in women.31 Similarly, educational differences could express the connection between education, income, and health care (e.g.,31). Regarding marital status, being unmarried may lead to experiencing demands that exceed older people coping strategies, and this imbalance eventually disturbs their health and functional status.32

As for emotion dysregulation, age was not an influencing factor, but in our study, age cohorts’ comparisons differed from those that found a decrease in maladaptive strategies with age.15,18 The absence of a decrease with older age could be explained by a reduction of cognitive flexibility, as Eldesouky and English33 suggested. Women had higher levels of emotional dysregulation, which is in line with the more suppression and rumination observed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Aldao.15 Older people with less formal education revealed higher levels of emotional dysregulation. Given the well-established relationship with depression, our finding is supported by investigations suggesting a protective role of education in depression.13

Our analyses showed that respondents with more disabilities or higher dependency had higher levels of depressive symptomatology. Other researchers previously ascertained the role of disability in depressive symptoms (e.g.,4). Others have found that physical and social disabilities compromise the quality of life and increase social isolation and dependency, which are related to depression.34

Disability also had a direct effect on emotional dysregulation, which means that higher dependency is associated with emotional dysregulation. As far as we know, this was the first study addressing these variables in old age, but the link is known in other age-independent diseases (e.g.,21). We also found an association between emotional dysregulation and depressive symptomatology corroborated by other studies.15,17

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show a (partially) mediated relationship between disability and depressive symptomatology in older adults. As hypothesized, disability was indirectly related to depressive symptomatology through emotional dysregulation. However, the mediation effect was small after controlling for covariates. This result, on the one hand, can indicate that other potential emotion regulation mechanisms are in place. Mechanisms such as mindfulness35 and cognitive control processes36 have been shown to be essential in emotion regulation. On the other hand, the mediation effect, being present in all older people groups, except in those with LTC-S, points to other processes involved in the LTC-S. Since disability does not predict more emotional dysregulation in this group, although it predicts more depressive symptoms, it is potentially because other aspects are potentially involved. Despite feeling sad about disability, older people with LTC-S do not need to avoid/ruminate/not-accept or engage in other maladaptive strategies due to potential fortitude and stoicism or acceptance regarding their situation.16,37 It could be that people having LTC-S accept disability as part of their condition.

Thus, our results indicate that older people with disabilities, especially those not having LTC-S, may experience less depressive symptoms if intervention focuses on emotional dysregulation, such as acceptance and commitment, mindfulness, and emotion regulation therapy therapies.35,37,38 Psychological treatments promoting emotion regulation and cognitive control processes over the development and persistence of depressive symptoms are likely to reduce depression in older people with disabilities. Special attention needs to be devoted if the older adults are women, widowers, and with less education. Due to the inconsistency of the mediational results in the group of older people in LTC-S, it is suggested that future studies examine the role of other aspects, such as the sense of fortitude, stoicism, acceptance, or other positive emotion regulation strategies.

LimitationsIn this study, some limitations should be reported.

First, considering that the study presents some limitations in population representativity and stratified sampling was not used, precaution is required before generalizing the present results to the national level and other cultures.

Second, participants were volunteers and were not randomly selected; thus, results may not be consistently reproduced, affecting the study's reliability. Due to social desirability bias, the participants may have underreported their problems and difficulties.

Third, cognitive functioning was not controlled despite the high variability in the cognitive decline process in older adults (e.g.,39).

Another limitation of the study was that only self-perceived disability was measured, but not the objective disability. Other variables were not controlled, like perceived discrimination, emotional, psychological, or psychiatric conditions that frequently co-occur in older people with a disability (e.g.,40).

Finally, we are aware that the study's cross-sectional nature limits interpretations of the directionality of effects between variables. Moreover, one could argue that mediational models are best tested with longitudinal data. However, the model is sustained by the reviewed literature, and such a model should be tested on a causal conceptualization of the relations between the variables under study.27

ConclusionOur findings indicate that older people with a disability are more likely to have depressive symptoms partially due to emotion dysregulation. Given this and considering that mindfulness35 and cognitive control36 have been shown to be mechanisms that regulate emotions, it may be important to design interventions for older people with disabilities that improve emotional regulation, such as mindfulness-based and cognitive therapies, to reduce depressive symptoms. However, future studies should examine the role of other aspects, such as emotion regulation strategies acceptance-related in older people receiving LTC-S.

Ethical approvalOur study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Miguel Torga Institute of Higher Education (CE-P11-18). All participants gave their permission to be part of the study and signed an informed consent form following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interestsThe Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsH.E.S. devised and supervised the project and the main conceptual ideas. H.S. contributed to collect and prepare the data. H.E.S. and H.S. performed the computations, conducted the analytical methods, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript draft. L.C. helped in the statistical analysis and proofreading. All authors provided critical feedback and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors wish to thank participants who agreed to take part in this study.