Energy balanceand malnourishment in instutionalized elderly

De Groot,L.

Division ofHuman Nutrition & Epidemiology. Wageningen University. TheNetherlands.

The worldwideraising number of people aged of 65 and over is well documented(1). Aging is known as «a process that converts healthyindividuals into frail ones, with diminished reserves in mostphysical systems and with exponentially increasing vulnerability tomost diseases and death» (2-4). This may negatively influenceenergy and nutrient use.

Further, inall aging populations, an adequate dietary intake has well beenrecognised as a necessary factor in improving longevity (5),maintaining good health (6) and quality of life (7).

Both Europeanand American health surveys have shown that at the age of 65-70 yand beyond, body weight tends to decrease, even in healthyindividuals (3, 8-12).

Involuntaryunexplained weight loss in later life increases the risk ofprotein-energy malnutrition, micronutrient deficiencies andnutrition-related illnesses and is associated with frailty andincreased morbidity (13).

This loss ofbody weight appears to go with a dysregulation in appetite controland energy intake which makes it difficult to compensate for theday to day fluctuation in dietary intake and subsequently may leadto malnutrition and progressive weight loss (14, 15).

Loss ofappetite occurring with age or so-called anorexia of aging has beendefined (16) as «the physiological decrease in food intakeoccurring to counterbalance reduced physical activity and lowermetabolic rate, not compensated in the long term».

Unintentionalweight loss has been found to occur in both institutionalised andnon-institutionalised elderly people and is associated withphysiological, psychological and immunologic consequences,regardless of the underlying causes (17-20).

Especiallyamong nursing home residents weight loss has traditionally beenmade a matter of concern. Yet, also among free-living frail elders,weight loss has been shown to be a predictor of early morbidity andmortality. These findings confirm the important role of losingweight as a major risk factor for the downward spiral leading tofrailty and mortality (21-26).

The etiologyof weight loss occurring with old age is multifactorial and in thisregard, anorexia of aging seems to be a key issue (27). Appetiteand the extent to which food is enjoyed vary greatly betweenpeople. In the elderly, these differences may be explained bydifferences in the health characteristics and eating habits of thegroups studied. Second, social and environmental factors remainimportant determinants of appetite, more especially in elderly withan unstable or poor health condition. Third, the incapacity toadjust energy intake in the elderly on both the short and long-termseems to be a non-reversible process. In daily practice, this lackof regulation suggests that the consumption of energy and nutrientdense supplements between meals could help to prevent weight lossin older adults.

From a publichealth perspective, the lack of regulation in appetite, dietaryintake and energy balance asks for nutritional interventions inelderly people residing in nursing homes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. INED. Population &sociétés. Bull Mensuel d'information de l'INED 1999(348).

2.Miller R. The biology of agingand longevity. En: Hazzard W, Bierman E, Blass J, Ettinger W,Halter J, Andres R, eds. Principles of geriatric medicine andgerontology. 3rd ed. New York: Mc Graw-Hill, Inc.; 1994. p.3-18.

3.Diehr P, Bild DE, Harris TB,Duxbury A, Siscovick D, Rossi M. Body mass index and mortality innonsmoking older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am JPublic Health 1998;88:623-9.

4.Lovat LB. Ageg related changesin gut physiology and nutritional status. Gut1996;38:306-9.

5.De Groot L, Van Staveren W,Burema J. Survival beyond age 70 in relation to diet. Nutr Rev1996;54:211-2.

6.Sullivan DH. Impact ofnutritional status on health outcomes of nursing home residents. JAm Geriatr Soc 1995;43:195-6.

7.Vetta F, Ronzoni S, Taglieri G,Bollea MR. The impact of malnutrition on the quality of life in theelderly. Clin Nutr 1999;18:259-67.

8.Cornoni-Huntley JC, Harris TB,Everett DF, Albanes D, Micozzi MS, Miles TP, Feldman JJ. Anoverview of body weight of older persons, including the impact onmortality. The National Health and Nutrition Examination surveyI-Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. J Clin Epidemiol1991;44:743-53.

9.Allison DB, Gallagher D, Heo M,Pi SF, Heymsfield SB. Body mass index and all-cause mortality amongpeople age 70 and over: the Longitudinal Study of Aging. Int J ObesRelat Metab Disord 1997;21:424-31.

10.De Groot C, Perdigao AL,Deurenberg P. Longitudinal changes in anthropometriccharacteristics of elderly Europeans. SENECA Investigators. Eur JClin Nutr 1996;(Supl 2):S9-15.

11.Lehmann AB, Bassey EJ.Longitudinal weight changes over four years and associated healthfactors in 629 men and women aged over 65. Eur J Clin Nutr1996;50:6-11.

12.Fischer J, Johnson MA. Low bodyweight and veight loss in the aged. J Am Diet Assoc1990;90:1697-706.

13.Mowe M, Bohmer T. Nutritionproblems among home-living elderly people may lead to disease andhospitalization. Nutr REv 1996;54:S22-4.

14.Zandstra E, Mathey M-F, deGraaf C, Van Staveren W. Short-term regulation of food intake inchildren, young adults and the elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr2000;54:239-46.

15.Roberts SB, Fuss P, Heyman MB,et al. Control of food intake in older men. JAMA1994;272:1601-6.

16.Morley JE, Silver AJ. Anorexiain the elderly. Neurobiol Aging 1988; 9:9-16.

17.Yeh SS, Schuster MW. Geriatriccachexia: the role of cytokines. Am J Clin Nutr1999;70:183-97.

18.Blaum CS, Fries BE, FiataroneMA. Factors associated with low body mass index and weight loss innursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci1995;50:M162-8.

19.Fabiny AR, Kiel DP. Assessingand treating weight loss in nursing home patients. Clin Geriatr Med1997;13:737-51.

20.Morley JE, Silver AJ.Nutritional issues in nursing home care. Ann Intern Med1995;123:850-9.

21.Mattila K, Haavisto M, RajalaS. Body mass index and mortality in the elderly. Br Med J Clin ResEd 1986;292:867-8.

22.Murden RA, Ainslie NK. Recentweight loss is related to short-term mortality in nursing homes. JGen Intern Med 1994;9:648-50.

23.Berkhout AM, Van HJ, Cools HJ.[Increased chance of dying among nursing home patients with lowerbody weight] (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd1997;141:2184-8.

24.Payette H, Coulombe C, BoutierV, Gray-Donald K. Weight loss and mortality among frail livingelders: a prospective study. J Gerontol Sci Med Sci1999;54:M440-5.

25.Allison DB, Zannolli R, FaithMS, Heo H, Pietrobelli A, Van Itallie TB, et al. Weight lossincreases and fat loss decreases all-cause mortality rate: resultsfrom two independent cohort studies. Int J Obes 1999;23:603-11.

26.Wallece JI, Schwartz RS, LaCroix AZ, Uhlmann RF, Pearlman RA. Involuntary weight loss in olderoutpatients: incidence and clinical significance. J Am Geriatr Soc1995;43:329-37.

27.Mathey, MFAM. Aging &appetite, social and physiological approaches in the elderly.Phd-thesis Department of Human Nutrition & Epidemiology,Wageningen University, The Netherlands, 2000. p. 1-120.

Sarcopenia andLoss of Function in Aging

Roubenoff,R.

Jean Mayer USDAHuman Nutrition Research Center on Aging. Tufts University. BostonMA. USA.

Normal agingis accompanied by loss of muscle quantity and quality. This declinein muscle causes a decline in strength, and eventually in theability to carry out activities required for independent dailyliving. There are many potential causes of this decline, which canbe summarized as an overall withdrawal of anabolic stimuli presentin youth, and of possibly an increase in catabolic stimuli as well.Among the potential mechanisms involved in sarcopeniaare:

* Loss ofcentral nervous system motor unit input into muscle.

* Loss ofgrowth hormone secretion.

* Loss ofandrogen and estrogen secretion (menopause, andropause).

* Inadequatedietary protein and energy intake.

* Increasedproduction of catabolic cytokines (IL-6, IL-1, TNF).

* Reducedphisical activity.

* Increasedfat mass (leading to insulin resistance and more TNF).

More is knownabout how to treat sarcopenia than about what causes it. Manystudies have shown that strength exercise training (progressiveresistance training) can reverse sarcopenia. Pharmacologicaltherapy is less well established, and at this time it is not clearif either growth homone or androgen therapy has a role to play insarcopenia treatment. The role of macronutrient and micronutrientdietary manipulations also needs much more extensiveevaluation.

Nevertheless,as the population ages, there is good reason to hope that anepidemic of frailty can be prevented by agressive application ofpublic health programs that emphasize physical activity and ahealthy diet.

Clinical aspectsof malnutrition

Enzi, G.; Sergi,G.

Department ofGeriatrics. University of Padova. Italy.

Severalpopulation studies demonstrate that some 5-10% of the home livingelderly are malnourished. The prevalence of malnutrition increasesto 26% in hospitalized patients and reach a maximum of 40-60% ininstitutionalized elderly patient.

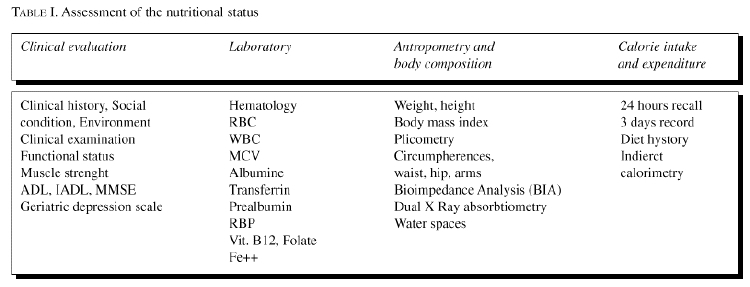

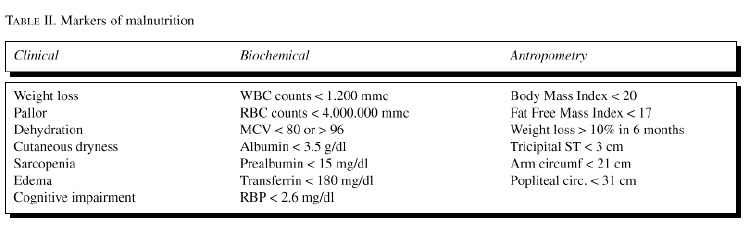

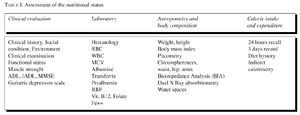

The clinicalapproach to the elderly patients at risk of malnutrition Tab. 1 and2 include:

1. An earlydiagnosis of malnutrition.

2. Ascreening of those individuals who need a nutritionalsupport.

3. A clinicaland biochemical definition of the type and severity of nutritionaldeficits.

4. A closecontrol of the efficacy of the nutritionalsupplementation.

The clinicalevaluation includes the signs and symptoms of malnutrition, i.e.:weight loss, associated diseases, drug assumptions, dietary habitsvariations, cutaneous and mucous lesions, pallor, edema.

Thefunctional evaluation includes the muscular strenght and thecognitive functions. The laboratory investigation includes themeasure of the visceral proteins (Serum albumin, pre-albumin,Retinol binding protein and transferrin) the iron status (red bloodcell count, serum iron, transferrine and ferritine) the vitaminstatus (Folate, Vit. B12 and other).

The record ofAnthropometric parameters (body weight, eight, body mass index,plicometry and arm circumferences) will provide useful information,namely in longitudinal population study.

Theevaluation of body composition with simple and unexpensive methods(Bioelectrical impedance analysis) gives relevant information onbody fat mass and lean body mass.

The loss oflean body mass (Sarcopenia) is a main sign of caloric-proteicmalnutrition. The Fat Free Mass Index (FFMI) = Body fatmass/Squared height seems to be a reliable marker of malnutritionand sarcoopenia. More sophysticated techniques, i.e. DEXA, bromidespace, deuterium or double labelled H20 allows accurate evaluationof body compartments and represent gold standards for thevalidation of other methods of measure. Finally, an estimate of theenergy intake and expenditure is a nutrient and caloric intake canbe evaluated trough the 24 hours recall, the 3 days diary the usualnutrient intake and the meals weight. The mini NutritionalAssessment seems to be a very useful and simple method to evaluatethe individual nutritional status. The energy expenditure at restand the substrate utilization can be evaluated by indirectcalorimetry and respiratory quotient calculation.

Folate, vitaminB12 and Vitamin B6 and One CarbonMetabolism

Selhub,J.

Jen Mayer USDAHuman Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University.Boston MA. USA.

Folate,vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 (and B2) are water-soluble vitamins thatfunction as coenzymes in one carbon metabolism. This metabolismcomprises of a network of interrelated biochemical reactions inwhich a one-carbon unit from a donor is transferred totetrahydrofolate for subsequent reduction or oxidation and/ortransfer of the one-carbon moiety for the synthesis of thymidylate,purine nucleotides, methionine or for serine-glycineinterconversion. Thymidylate and purine nucleotides are used forDNA and RNA synthesis and repair. Methionine is used for proteinsynthesis and for the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), theuniversal methyl donor.

Vitamin B12,in the form of methyl B12, participates in the methylation ofhomocysteine to from methionine. FAC, the coenzyme form ofriboflavin (B2), acts as a prosthetic group formethylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Pyridoxal-5'-phosphate (PLP)is used for the serine-glycine interconversion as well as for thedisposal of homocysteine through the transsulfurationpathway.

Interest inone-carbon metabolism, as a public health issue, has been growingsince the demonstration that periconceptional intake of folic acidprevents the occurrence and recurrence of neural tube defects. Thisinterest emanates from reports which link inadequate vitamin statusor intake, or higher plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) levels, toincreased risks of a variety of diseases that afflict the elderly,including occlusive vascular disease, cancers, cognitivedysfunction and others.

In 1992, weproposed a hypothesis to explain the biochemical regulation ofplasma tHcy levels (Selhub and Miller, 1992). Our premise was thatplasma tHcy concentration is a reflection of the intracellularmetabolism of homocysteine. Furthermore, since tHcy metabolism iscatalyzed by enzymes that employ folate, B12, B6 and B2 coenzymesfor their activities, we postulated that the amount of homocysteinein plasma is determined by the status of these vitamins as well asby regulatory checkpoints in the metabolic scheme which aremodulated by metabolic intermediaries such as SAM, the levels fowhich are also in part determined by B-vitamin status.

We usedvitamin deficient rat models to support many aspects of thishypothesis (Miller et al, 1994). In the Framingham Study, we showedthat plasma tHcy levels are strongly and inversely correlated withplasma folate levels (Selhub et al, 1993). Plasma tHcy levels werealso inversely correlated with both plasma vitamin B12 and PLPlevels, although to a lesser extent than the relationship withplasma folate. Similar data were obtained with the analysis of USrepresentaive serum samples from NHANES III (Selhub et al,1999).

The use ofhomocysteine and methylmalonic acid (MMA) as functional indicatorsof vitamin status has been useful in clarifying the diminishingvitamin status in the elderly. Thirty percent of the elderly in theFramingham Study original cohort had elevated tHcy plasma levels,and 2/3 of these elevations is attributable to inadequate vitaminstates (Selhub et al, 1993). In NHANES III, the relationshipbetween tHcy and serum vitamin B12 levels is most evident in thoseover the age of 60 years. Serum MMA levels in the Framingham Studyhas been valuable in estimating the proportion of the elderly withinadequate vitamin B12 status (Lindenbaum et al, 1994).

Incardiovascular disease, emphasis has been placed on therelationship with tHcy. Nearly all observational studies that haveexamined this issue have demonstrated a highly significantrelationship. In the Framingham study, we showed a strongassociation between prevalence of carotid stenosis and tHcy levels,as well as with plasma folate and PLP levels (Slhub et al, 1995).There have been few other studies that showed similar relationshipsbetween disease and systemic vitamin levels or estimated intake(Robinson et al, 1998). The majority of the studies, however,either did not measure blood vitamins or found no significantrelationships between blood vitamin levels and disease.

Neurodegenerative disease due to B12 deficiency has beenrecognized for years, whereas epidemiological evidence linking lowfolate and B6 status with a decline in neurocognitive function inthe elderly was first described by Goodwin et al (1983). Theydemonstrated that healthy elderly subjects with low blood levels orlower intake of folate, vitamin B12, vitamin C and riboflavinscored more poorly on tests of memory and nonverbal abstractthinking. Other studies (reviewed by Selhub et al, 2000) have, forthe most part, reiterated these epidemiological associationsbetween vitamins and neuropsychological functions, while a fewother studies reported improvement in mental health after vitaminsupplementation (LIndenbaum et al, 1988; Martin et al, 1992). Theseobservations argue that poor vitamin status is in part responsiblefor the cognitive decline seen in some elderly.

Morerecently, elevated plasma homocysteine levels have been related tocognitive dysfunction and subsequent studies suggest that therelationship of cognitive dysfunction and dementia to plasma tHcyis stronger than the relationship to plasma vitamin levels(reviewed in Selhub et al, 2000). Plasma tHcy was a far strongerpredictor for spatial copying performance than either folate orvitamin B12 (Riggs et al, 1996). Plasma tHcy also exhibited astronger correlation to dementia of Alzheimer's type (DAT) in 164consecutive patients, including 76 patients with histologicallyconfirmed diagnoses (Clarke et al 1998). Finally, Lehmann et al(1999) showed tHcy, but not vitamin levels, inversely correlatedwith the degree of memory loss.

Fassbender etal (1999 found that patients with small and subcortical vascularencephalopathy (SVE), a distinct type of vascular dementia which ischaracterized by progressive loss of memory, cognitive decline andother manifestations, have higher tHcy than both healthy controlsand patients with large vessels cerebrovascular disease. Regressionanalysis revealed that tHcy is the strongest independent riskfactor for SVE.

Low folatestatus, and more recently, low B12 and B6 status have beenassociated with increased rates of certain types of common cancers.Observational studies of a case-control as well as prospectivecohort design have consistently demonstrated a 40-60% decline inthe development of colorectal neoplasm when comparing populationsconsuming high versus low folate (reviewed in Kim, 1999). Dietscontaining low levels of methionine and excessive alcohol, each ofwhich would be expected to further impair one carbon metabolism,contribute to the risk of low folate intakes in the prospectivecohort studies (Giovannucci et al, 1993, 1995).

There arethree addtional observations that contribute evidence that lowfolate status actually contributes to the risk of developing thecancer. We have conducted two studies with animal models ofcolorectal cancer demonstrating an inverse dose-response effectbetween dietary folate intake and the development of bothmicroscopic foci of cancer as well as macroscopic tumors (Cravo etal, 1992; Kim et al, 1996). in the Physician's Health Study weobserved that homozygosity for the C677T mutation is associatedwith a 70% reduction in the relative risk of colorectal cancer (Maet al 1997) in those with a normal folat status. Lastly, we andothers have performed numerous studies in cell culture, animalmodels and in humans which provided several biologically plausiblemechanisms by which folate status might modulate colorectalcarcinogenesis. These mechanisms largely relate totetrahydrofolate's prominent role in sustaining critical patternsof DNA and RNA methylation as well as its role in thymidylate andpurine synthesis and thereby in sustaining normal DNA synthesis andrepair. We have shown that folate deficiency in rats leads tohypomethylation of the critical regions of the p53 tumor suppressorgene as well as a concurrent excess of strand breaks in the sameregion (Kim et al, 1997) Recently, our group proposed a scheme thatintegrates the most likely mechanisms that are responsible forfolate's modulation of carcinogenesis into a unified explanationfor the effect (Choi & Mason, 2000).In addition, we havecollaborated with the nutritional epidemiology group at theNational Cancer Institute to begin to explore the relationship ofB12 and B6 with cancer. Low plasma vitamin B12 is associated with a2-fold increase in breast cancer risk (Wu et al, 1999); in malesmokers, low PLP and folate levels are associated with increasedpancreatic cancer risk (Stolzenberg-Solomon et al, 1999) and lowPLP increases the risk of lung cancer (Hartman et al, 2000). Innone of the cases does tHcy exhibit any significant relation withdisease risk.

Minerals

Vaquero, M.P.

Instituto deNutrición y Bromatología (CSIC-UCM). Madrid.Spain.

Ageing ischaracterised by an increase in the capacity to adjust toenvironmental and intrinsic changes finally affecting survival.Homeostatic mechanisms breakdown and nutrient bioavailability,including that of minerals, declines.

Poor intakeof minerals and interactions between them and other components ofthe diet may lead to deficiencies. Imbalances between mineralintakes and recommended amounts have been observed in differentgroups of elderly. However, except perhaps for calcium and iron,assessment of mineral status is difficult, because they participatein many metabolic functions.

Among themajor minerals, calcium absorption efficiency and its acreetioninto the bone is known to be low during elderly. In contrast,metabolic processes that lead to bone resorption and body calciumlosses are enhanced. Bioavailability of other minerals such asmagnesium and that of trace elements, such as zinc, selenium,chromium, etc, may also change due to ageing. Old people do notneed food to grow but to maintain body functions. The relationshipdiet-health is especially relevant at this stage. Age-dependentdiseases in which minerals may play a role include: cardiovasculardisease, osteoporosis, cancer, hypertensión, anaemia,diabetes mellitus, and macular degeneration.

Moreover, inthe elderly interactions between nutrients may change andmedication to treat chronic diseases may interfere with mineralutilisation. Therefore, formulation of mineral recommendation iscomplex and individual recommendations are sometimesneeded.

Recommendediron intake is lower for older women compared to young, becausemenstruation ceases after menopause. In contrast, recommendedcalcium intakes are higher in order to protect from osteoporosis.Dietary recommendations for the rest of elements are similar tothat of adults, although several suggestions on the quantities havebeen given. Electrolytes, particularly sodium and potassiums houldbe considered, because the renal capacity to conserve and excretewater and electrolytes is usually altered compared to adults.Consequently, control of salt intake should be prometed in order tolower the hypertension risk, but al the same time preventing anexcessive reduction of sodium intake that could producehyponatremia.

This reviewexamines various aspects of the changes on mineral bioavailabilitydue to ageing, of data published on mineral intakes and status inthe elderly, and finally the dietary recommendations for thisvulnerable group of population.

Improvingappetite in the elderly

De Graaf,C.

Department ofHuman Nutrition and Epidemiology Wageningen University. Wageningen.The Netherlands.

Background. More than 50% of elderly in Dutch nursinghomes has a lower than recommended intake of at least onemicronutrient. The high prevalences of low micronutrient intakescan be attributed to a low food intake, which may result from a lowappetite. One possible cause of this so-called anorexia of agingmay be of sensory origin, another cause may be of socialorigin.

Objective. To determine whether interventions in thesocial or sensory domain improve appetite, food intake andnutritional status.

Methods. In a 1 year intervention we improved the socialambiance at mealtime in two somatic wards (with n= 15 in each ward)of a nursing home, by a series of measures related to 1. theserving of the meal, 2. physical environment (making it more cosy),and 3. participation of nursing staff in the meal. In two controlwards, there was no change from the original mealtime situation.Foods served in both conditions were identical, and the measureswere carried without extra (labour) costs. Dependent variables inthis study were body weight, food intake (3 d. observed),haematological parameters, and quality of life. In other studies,not reported in this abstract we did interventions within thesensory domain.

Results. The average weight in the intervention group(n=12) increased by 2.8 kg (p<0.05), whereas in the controlgroup (n=10) there were no weight changes. There were no noticeableeffects of measured food intake. Quality of life remained stable inthe intervention group, while it declined in the control group.Some haematological parameters improced in the intervention groupwhile they remained stable in the control group.

Discussion/conclusion. Improving the social ambiance atmealtime in nursing homes has positive effects on nutritionalstatus and quality of life. The social ambiance at mealtime canplay an important role in improving appetite in elderly. A similarconclusion can be drawn with respect to sensory factors.

Food likes anddislikes in elderly people

Briz, J.; DeFelipe, I.

PolytechnicUniversity of Madrid. ETSIA. Madrid. Spain.

Although mostof the current studies have been focus to young and middle agepopulation, elderly people are becoming a significant group inwestern countries, with political, social and economic importance.Therefore, an important issue in a market economy is to know thereasons why they likes or dislikes food, to understand the buyingprocess.

On the otherhand consumer behaviour is very complex due to the influence ofmany factors. Therefore the research focus to food likes anddislikes requires the knowledge of several sciences such associology, nutrition, physiology, sensory analysis, medicine,marketing and others.

The consumerdecision process follow different steps that we may identify asneed recognition, search for information, evaluation ofalternatives and choice.

In needrecognition, consumers may experience a need for stimulation.Through marketing activities enterprises inform the consumers aboutthe attributes and advantages of their products. However we shouldkeep in mind that old persons prefer the written information thatmay check, read carefully an understand better.

Search forinformation is the next step, and most of the elderly people havehad previous opportunities for traditional food. However they facea barrier for new products, with no former experience beenreluctant to them due to their special conditions of taste, smell,health and price.

In theevaluation of alternatives elderly people tend to think about foodin relation to the function. There is a priority on theconsequences on health while are secondary other elements such aslabel, preservation or color.

Thegeographic origin of the food may be an important factor in foodchoice. Elderly people have a long life and they have positive andnegative experiences influencing food likes anddislikes.

In generalconsumer choice behavior may be influenced by socioeconomicenvironmental conditions and by psychological effects. Although itmay be a diminished economic status in the elderly, specially thoseretired with lower income, several factors indicate the relativeincrease in food expenditures. Rising incomes on the elderly willlead to higher per capital food expenditures. We know that when lowincomes rise, more food is usually consumed, and many elderly arein the lower income step. Old adults living alone spend more perperson in food than larger households. Besides they demand smalleror single serving packages with higher cost per unit. Also demandfor convenience and services may increase in several ways: foodpackaging, ready to eat, home delivered or eaten away fromhome.

As they havemore spare time, food shopping is a major activity for many elderlypeople. There are opportunities for home-delivered food at areasonable price, but the social function of shopping is veryimportant for the elderly.

However theyface some difficulties as a consequence of diminished physicalstrength necessary for lifting heavy loads, handling carts, walkinglong distances.

Physiologicaleffects are significant. Ageing is usually accompanied by anorexia:a decline in appetite followed by weight loss. Appetite changegreatly among people. In the elderly these differences mayfrequently explained by differences in health. We should considerthat aging bodies need fewer calories, because physical activityslows, muscle mass is lost and often replaced by fat. Because fattissue burns fewer calories than muscle, fewer calories are need tomaintain body weight.

However wemay get some solutions to balance the alternative food like ordislike. Thus, the consumption energy vitamin drink and nutrientdense supplements between meals may prevent their weight loss. Someother times adding ready to use flavor enhancers to the meals wasan effective way to improve food likes.

One opportunequestion is how western society response to elderly people needs? Ashort discussion is showed about the action of public and privatesector. How public institutions should adapt their programs toincrease food intake and health in old population.

Commercialoriented to «third age» are related to insurance,retirement of recreation activities. However in food sector bigchanges are appreciated. Promotion is usually focus to young anddynamic persons.

Foodproducers and distributors should also adapt their marketingstrategies looking at the potential of the new market segment. Theyshould avoid common mistakes creating new products for«senior citizen». Quite often old people do notidentify individually as member of the old age. After, in thispaper there is a description of the food intake evolution of theSpanish old population, with a comparative analysis of the mainbasic products.

A decrease inthe consumption of fresh fruit and vegetable and other typicalMediterranean products during last decades called the attention tosome nutritionists that see a degradation of our healthydiet.

A seriousanalysis of the reasons should be done. Why fresh fruit aresubstituted by dairy products as dessert? It is the more variety ondairy that make them more atractive? Why do people like more the«imported» food habits? Why did not like sometraditional, healthy and creap products (such as beans, lentiles,garbanzos)? Is it a consequence of globalization, promotion, pricecompetition, or more dynamic distribution?

Those aresome questions to be answered by producers, specialist, merchants,politicians or consumer associations. Something has to be done tomaintain our traditional Mediterranean food habits.

Nutritionalproblems in nursing home

Ribera Casado,J. M.

Servicio deGeriatría. Hospital Universitario San Carlos. Madrid.Spain.

More than 6million people in Spain are over 65 years-old (16%). We will beover 20% before year 2020th. With 80 years or over are 1.350.000.Life spectancy at 65, is 20 years in women, and 16 in men. Healthand related health problems are the main concerns for theelderly.

Thenursing-home world is a very complex one. We could clasifynursing-homes according with different schedules. Mainly size anddependence, both with effect on the nutritional status and problemsof residents. The number of nursing-homes beds in Spain were in1998 of 188.862; a little more than two-thirds (130.369) areprivate.

Changesassociated to the human aging process are clasified asphysiological, pathological and related to enviromental and riskfactors. Nutritional changes arrive by any of these ways. In anursing-homes we must add as specially critical situations: acuteintercurent processes, use and abuse of drugs, and several diseaseslike tumors or dementia.

There are notmany nursing-homes dietetic-nutritional studies carried out in ourcountry. Among them, along the last ten years, I willrefer:

a)«Estudio Canarias» (Morales et al. 1991).

130nursing-home residents (71 years old).

Nutritional status was worse in those with:

* cognitiveimpairment.

*deambulatory dificulties.

* need ofhelp to eat.

Mortality at 20 month was close related with a worse basalnutritional status.

b)«Cataluña» (Salvá et al.1996).

Nutritional assessment in Catalonia nursing-homes.

Instrument: Mini-Nutritional-Assessment.

Undernourished residents: 5.7%.

Inrisk: 47%.

c)«Sociedad Española de Geriatría-IMSERSOStudy» (1998).

1152residentes, living in 35 nursing-homes all around thecountry.

BMI> 20: 4%.

d)«Nutricia Study in Nursing-Homes» (1998).

582healthy residents (81 years old).

Public nursing-homes (Andalucía, Cataluña andGalicia).

* 30% neededsome special diet.

* Nutritionalstatus were good.

* 14% drunkalcohol daily (mean: 16 gr/day).

e)«Demenu-Study». Madrid (2000).

99demented patients (86 y.) living in nursing-homes.

Dailynutritional suplements with one year follow-up.

Nochanges in the evolution of dementia.

Lessmorbi-mortality.

Main concernsrelated to nutrition in the elderly at nursing-home are: a) lossesof weight and malnutrition, b) dehidratación, c)hyponatremic status, d) comorbidity, e) demented patients, f)special diets, and g) patients with parenteral nutrition or withgastrostomy.

Nursing-homepolicy must include: a) assessment of nutritional status atarriving and periodically, b) to provide healthy foods and a wellbalanced diet, and c) to respond in every case to the nutritionalneeds of the resident.

Some generalsuggestion related to the diet are:

Toavoid an uniform diet or forbidden foods in an age-basedpolicy.

Toprepare menus according with the cultural habits of theresidents.

Anatractive presentation of the foods.

Todivide the diet in 4 or 5 daily meals schedule.

Residents must eat the liquid component of the meals, in order toget profit from there minerals and vitamins. To avoid (or toreduce) frites. To consume fuits and fresh vegetables.

Aminimum of 1,5-2 of liquids each day (water, milk, juice,infussions, etc.).

In case ofmalnutrition the protocol will include:

To lookfor and to treat the eventual precipitating disease.

Toassess the efects on the different systems: weight, blooddeterminations (haemoglobin, albumine, cholesterol,...).

Tostart an incentivated and supervised open dietetic program adding,allowing a free diet, with, if necessary, oral nutritionalsupplements.

Ifafter one month BMI shows not response or albumine level are below< 2.8 gr/dl we can start with enteral nutrition (nasogastrictube).

Micronutrientstatus and mental health

Haller,J.

F. Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd. Vitamins and Fine Chemicals Division. Human Health andNutrition. CH-4070 Basel. Switzerland.

Mental healthpartly reflects the functional and structural condition of thebrain, which in turn is dependent on its supply of nutrients andoxygen. Vitamins play a direct role in the synthesis of the majorneurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, dopamine, noradrenaline,serotonin and GABA. Acetylcholine is involved in the mechanisms ofattention and memory, noradrenaline and serotonin are involved incontrolling mood and GABA is involved in modulating anxiety. Thevitamins with antioxidative properties such as ascorbic acidand *-tocopherol aid theendogenous mechanisms in combating lipid peroxidation and oxidationof neurotransmitters. Animal studies have shown that vitamin Ereduces the neurotoxicity of ß-amyloid and in one human intervention study the progress ofAlzheimer's disease could be slowed by treatment with vitamin E.The brain's function also reflects the performance of thecardiovascular system, as it receives 19% of the body's bloodsupply and 20% of the oxygen supply. Epidemiological studies haveshown that there is an inverse relationship between the plasmalevels of homocysteine and carotid artery stenosis and between theformer and the levels of vitamins B-6, B-12 and folic acid.Intervention studies have shown that these vitamins lower the bloodlevels of homocysteine and methylmalonate and reduce theprogression of atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries.Epidemiological studies suggest that populations with higher plasmalevels or higher dietary intake of folate and vitamin B-6 have alower risk of carotid artery stenosis and coronary heart disease.The B-vitamins therefore play an important role in maintaining anoptimal blood supply to the brain throughout life. In manyepidemiological studies correlations have been found betweenvitamin intake or vitamin plasma levels and various markers ofmental health.

Phisicalperformance and quality of life

Schroll,M.

Departament ofGeriatrics. Bispebjerg Hospital. Copenhagen. Denmark.

Objective: To describe the predictive power of ADL, age76-80, for Quality of Life, live years later.

Design: ADL measured at SENECA survey 2, 1993 wasrelated to Quality of Life measured in SENECA survey 3, 1999 in 532men and women from 8 European countries. 310 persons from SENECA 2had died 1993 - 1999, and 249 did not participate in1999.

Methods: For Activities of daily living (ADL) 16 itemsthe level of competence was measured on a 4-point scale andcombined ability scores calculated.

Differentdimensions of Quality of Life questions (QoL) pain, sleep, energy,emotions, social network, physical performance have been formed assum scores of answers (yes/no) to ingoing questions.

Results: For each gender and in almost every countryability to perform ADL (1993) was almost doubling the chance toomit pain, slee-plessness, loss of energy, depresion, lonelinessand impaired mobility (p< 0.05).

Discussion: Participants in SENECA survey 3 were themost healthy and well functioning of the survivors in 1999 born1913-18. Even in this group of healthy survivors a gradient in QoLcould be detected, associated with former ADL performance. Ifmortality and nonparticipation had been less, 1993-1999, thepredictive power of ADL for QoL could have been evengreater.

Type 2 DiabetesMellitus and Cognitive Dysfunction

Sinclair,A.

University ofBirmingham. Department of Geriatric Medicine. Selly Oak Hospital.Birmingham. United Kingdom

Type 2Diabetes mellitus and cognitive dysfunction appear to be relatedalthough other factors such as hypertension, depression, anddyslipidaemia may play a role. Whilst the complications of diabetesmellitus have been extensively studied in the micro- andmacrovascular systems, relatively little is known about the effectof this metabolic disorder on longer term cerebral and cognitivefunction. This dysfunction is likely to result from severalfactors, for example, the presence of co-existing cerebrovasculardisease, metabolic decompensation, hypoglycaemia, or even theeffect of persistent hyperglycaemia.

This lecturewill provide a summary of the literature in this area, discussseveral underlying mechanisms which may operate to producecognitive impairment and dementia, and look at possible ways ofgaining greater insight into this probable complication ofdiabetes. The implications of having this complication will bediscussed briefly in terms of management strategies. A briefaccount of the Welsh Community Diabetes Study (the AWARE Study)will be given with data presented relating cognitive function andits impact on use of healthcare services and self-carebehaviour.

SENECA's FINALE:Dietary quality, lifestyle factors, nutritional status and survivalin old age

Van Staveren, W.A.; Haveman-Nies, A. and De Groot L., on behalf of the SENECAinvestigators.

Department ofHuman Nutrition and Epidemiology. Wagenigen University. TheNetherlands.

The SENECAstudy is a Europe-wide study among mostly free living elderlypeople who have been followed for a period of ten years. The aim ofthis study was «to explore dietary patterns in the elderlyliving in different European communities in relation to both socialand economic conditions and to health and performance». Inthis paper we present the first results of SENECA's FINALEfocussing on dietary quality, lifestyle factors, and nutritionalstatus and their relationship with survival. The SENECA studystarted in 1989, included an intermediate measurement schedule in1993 and the FINALE data collection was conducted in1999.

At baseline,participants were a randomised stratified sample from 19 centresstratified for age and sex. About 2600 elderly people, with anequal number of men and women participated. At that time they were70-74 years old. For this presentation we use data of about 50% ofthe original participants, including those with full longitudinaldata sets.

The followingmeasurements were included in the core protocol atbaseline:

General questionnaire. Including questions on socialdemographic data, health, medicine use, supplement use, physicalactivity and performance.

Dietary intake. Validated modified diet history, including a3-day diet record.

Anthropometry. Body height and weight, othermeasurements.

Biochemistry. Several vitamins, lipids, albumin andhaematology.

Nonresponse. Questionnaire.

In SENECA'sFINALE we added questions on mental health (also included in thefollow-up study in 1993), vital status and quality oflife.

So far, weonly explored diet, physical activity, body mass index(Kg/m2) and smoking in relation to survival.

Examiningdiet two macronutrient profiles emerged: a northern profile withcomparable contributions of carbohydrate and total fat to totaldaily energy intake and a southern profile with a larger share ofcarbohydrates to total energy intake. We decided to use forexploring the relationship between diet and survival theMediterranean diet score as developed by Trichopoulou et al andonly made small adaptations in the cut-off values. The followingitems were included in the score:

monounsaturated/saturated fat ratio;

grains;

fruitsand products, vegetables;

alcoholic beverages;

meatand poultry;

milkand milk products.

Por physicalactivity we used tertiles of the Voorrips-score.

Smokers werecategorised in current- ex- and no smokers.

During thelecture we will discuss the results of our explorative analysis.Preliminary analyses indicate that a healthy lifestyle stillmatters: even at ae 70-75 years.

REFERENCES

De Groot CPMG, Van Staveren WA,Hautvast JGAJ. Euronut-SENECA: A concerted action on nutrition andthe Elderly in Europe. Eur J Clin Nutr 1994;45(supl3):196.

Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A,Wahlquist ML, et al. Diet and overall survival in elderly people.BMJ 1995;311:1457-60.

Voorrips LE, Eavelli ACJ,Dongelmans PCA, et al. A aphysical activity questionnaire for theelderly. Med Sci Sports Exercise 1991;23:974-9.

Micronutrientsand drug interactions in elderly

Ferry, M.*;Roussel, A. M.**

* Service deGeriatrie. Centre Hospitalier de Valence Cedex. ** LBSO.Université Joseph Fourier. La Tronche. France

A variety ofphysiological, economic, psychological and social changes cancompromise the nutritional status in elderly. Regardingmicronutrients, the functional decline of gastrointestinal, renal,and endocrine functions result in a reduction of theirbioavailability and in a modified metabolism. Parallely, the needsare increased to restore immunity (Zn, Se, Cu, Vitamin E, C), toimprove glucose tolerance and lean body mass (Cr), to maintaincognitive function (Se, ßcarotenes, vitamin E, folates), to prevent bone density loss(Ca, Cu, Zn), and to protect against oxidative stress (Zn, Se, Cu,vitamin E, C, carotenes). In free living people, alterations ofmicronutrient status are reported to be at moderate incidence.However, in SENECA study, we observed inadequate intake of one ormore nutrients in 23.9% of men and 46.8% of women 74-79 years oldliving at home. In hospitalized or institutionalized elderlypatients, several recent surveys have reported a high incidence ofcombined vitamin and trace element deficiencies due both to acute(e.g. cancers, CVD) or chronic diseases (e.g. inflammatory chronicdisorders) that generally increase the needs and to medicationsthat modify the absorption and metabolism ofmicronutrients.

MODIFICATIONS OF MICRONUTRIENT ABSORPTION ANDMETABOLISM

One mode ofaction of dietary enhancers and inhibitors is to elicit a change ofabsorption through the formation of complexes with the traceelement in the GI tract. I f the binding of the trace elementwithin the complex is very tight, then the trace element may not bereleased to the transport protein associated with the enterocytes;the substance is then an inhibitor e.g. phytate with iron and zinc.Conversely, if the binding of the compound is lower that of thetransport protein, then the trace element will be released from thecomplex and the result will be an enhanced absorption. Substancesclassed as enhancers include ascorbic acid with iron, amino acidswith Cr, Cu, Zn, Fe. The formation of these complex is highlydependant of the gastric pH. In aged patients, the decreased acidgastric secretion, associated to a lowered acid lipase secretionleads to a lower iron absorption. Zinc and selenium seem lessinfluenced by gastric pH.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN NUTRIENTS

Competitiveor synergistic interactions also occurs between micronutrients.Hundreds of interactions among mineral elements and/or vitamins andbetween those and other nutrients are known but have not beenquantified. The quantitative description of all these interactionsis probably the treatest challenge for assessment of the efficientyof a supplementation. For trace elements, the antagonism issignificant when the intake of one metal is particularly high. Theinteractions occur mostly between zinc and copper, zinc and iron,zinc and folates, iron and copper. Calcium reduce magnesium, ironand zinc absorption and balance. In post menopausal women, lactosemay interfere with copper metabolism and be, surprisingly, anaggravating factor of osteoporosis. For vitamin E, synergisticeffects of selenium, vitamin C or sulfur containing amino acids arewell documented, with high intakes of vitamin A may decreasevitamin E absorption. Conversely, high levels of vitamin E reduceintestinal absorption of vitamin K.

MICRONUTRIENT AND DRUG INTERACTIONS

Oldersubjects frequently receive several combined treatments which caninterfere with micronutrient metabolism and status. It is welldocumented that a polymedication induces inappetence and results inlow nutritional intakes, which lead to an inadequate intake ofmicronutriments. Moreover, specific mineral traces such aspotassium, magnesium and zinc appear to be important for optimalIGF1 synthesis and anabolic effects on animal models. Drugs andmicronutrient interactions in elderly are not well documentedalthough they frequently occur. Vitamins taken in large dosagesshould be considered as drugs. High doses of vitamin C aggravatethe decline of renal clearance of acidic drugs such asacetylsalicylic acid. Vitamin B6 reduces the therapeutic effect ofL-Dopa. Vitamin E interacts with numerous medications asclofibrate, isoniazid, cholestyramine, adriamycin, warfarin,phenothiazines. Conversely, drugs can modify vitamin metabolism.Anticonvulsives that induce hepatic microsomal enzymes acceleratevitamin D metabolism and aggravate post-menopausal osteoporosis.Antiacids and hydrogen pump blocking agent develop bacterialovergrowth of the small intestine and decrease the absorption offolates, calcium, vitamin B12 and vitamin K. But this overgrowthproduces also menaquinones which contribute to vitamin K nutriture.Some drugs are well known to interfere with minerals. Diureticsusually decrease potassium, magnesium, zinc and long term diuretictherapy, which is the most widely used in cardiac failure,increases urinary excretion of water soluble vitamins, particularyB1. Antidepressant treatmment can alter zinc status.Antiinflammatory drugs interact with zinc and copper. Recentlyinteractions between chromium and corticosteroids have beenreported. Atherogenicity of homocysteine may be related tocopper-dependent interactions. Antioxydant balance can also bemodified by some drugs. In women with breast cancer, tamoxifenresulta in an increase of antioxidant status as vitamins E, C, andselenium, whereas the effect is not found with cisplatin which actsconversely as prooxydant.

Inconclusion, regarding the importance of these interactions, thedata are still scarce, and further studies are needed for a betterknowledge and an optimal effficiency of treatments.