Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a syndrome characterized by progressive parkinsonism with early falls due to postural instability, typically vertical gaze supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, pseudobulbar dysfunction, neck dystonia and upper trunk rigidity as well as mild cognitive dysfunction. Progressive supranuclear palsy must be differentiated from Parkinson's disease taking into account several so-called red flags.

Materials and methodsWe report a case series hallmarked by gait abnormalities, falls and bradykinesia in which Parkinson's disease was the initial diagnosis.

ResultsDue to a torpid clinical course, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed demonstrating midbrain atrophy, highly suggestive of progressive supranuclear palsy.

ConclusionThe neuroradiological exams (magnetic resonance imaging, single photon emission computer tomography, and positron emission tomography) can be useful for diagnosis of PSP. Treatment with levodopa should be considered, especially in patients with a more parkinsonian phenotype.

La parálisis supranuclear progresiva (PSP) es un síndrome caracterizado por parkinsonismo progresivo con caídas tempranas secundarias a inestabilidad postural, oftalmoplejía supranuclear típicamente de mirada vertical, disfunción seudobulbar, distonía de cuello y tronco superior, rigidez y deterioro cognitivo moderado. La parálisis supranuclear progresiva debe ser diferenciada de la enfermedad de Parkinson tomando en cuenta las llamadas banderas rojas.

Materiales y métodosReportamos una serie de casos distinguidos por anormalidad de la marcha, caídas y bradicinesia, en quienes el diagnóstico de inicio fue enfermedad de Parkinson.

ResultadosDebido a un curso clínico tórpido se realizaron resonancias magnéticas que demostraron atrofia mesencefálica altamente sugestiva de parálisis supranuclear progresiva.

ConclusiónEl examen neurorradiológico (resonancia magnética, tomografía por emisión de positrones y tomografía simple) pueden ser útiles para el diagnóstico de PSP. El tratamiento con levodopa debe ser considerado especialmente en pacientes con fenotipo parkinsoniano.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), first described in 1963 by Richardson, Steele and Olszewski, is an uncommon rapidly progressive degenerative disease.1 PSP has a strong male predominance with a typical presentation in the 5th or 7th decades with a mean age of onset of approximately 63 years. The mean survival is about nine years after the symptom onset. The prevalence of PSP is estimated to be between 1.4 and 5.3 per 100,000. The highest prevalence of PSP has been recently reported in the French Antilles, with a minimum prevalence of 14 per 100,000 in the island of Guadaloupe.2–4

From a pathological view, PSP is classified as a tauopathy along Alzheimer's disease (AD), Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and frontotemporal dementias.5 Genetic studies have demonstrated an overrepresentation of polymorphisms and haplotypes on chromosome 17q21 that predisposes the development of PSP, yet the genetic background is insufficient to cause the disease.6,7 The resulting dysfunction of dopaminergic, GABAergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic pathways are responsible for the symptoms of PSP.8

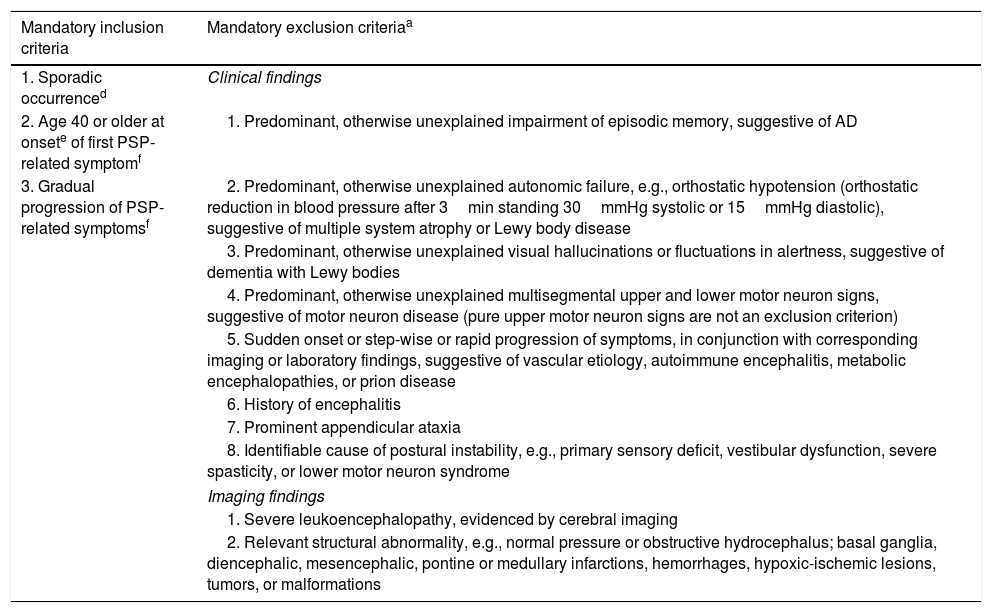

Current diagnostic criteria are based on mandatory basic features, mandatory exclusion criteria and context-dependent exclusion criteria. According to these criteria, PSP diagnostic certainly can be classified as probable PSP, possible PSP and suggestive of PSP, still, the definite PSP requires neuropathological confirmation.9

The current pharmacological treatment of PSP is based on poor evidence and low recommendation grades due to a lack of clinical trials. Most patients will be trialed on l-DOPA and amantadine. Unfortunately, although well tolerated, their clinical response ranges from none to moderate, and is not sustained.10,11

Since parkinsonism is usually a major feature of PSP, the main differential diagnosis includes Parkinson's disease. From a clinical standpoint there are several “red flags” useful to differentiate between these two diseases. In addition, neuroimaging techniques can also aid in improving the diagnostic accuracy.

Materials and methods: case series reportWe present four cases initially diagnosed as PD, in which the atypical course led to further reassessment resulting in PSP diagnosis.

Patient 1An 81-year-old male with a history of hypertension and no history of family neurodegenerative diseases. At the age of 70 years he developed micrographia, clumsiness of fine hand movements, bradykinesia, gait abnormalities and repeated unprovoked falls; within five years he presented progressive freezing of the gait. One year later he developed gait start hesitation, transient motor blocks, speech alterations (slow, low volume and pitch), parkinsonian facies, back pain and axial rigidity, dysphagia, as well as vertical supranuclear gaze palsy without cognitive decline. The falls became more frequent up to four times a day. Treatment with levodopa was started without improvement. Eight years after the symptom onset a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the Brain T2-weighted was performed, showing mesencephalic atrophy; with a decrease in tegmentum and relative conservation of the protuberance size, bilateral degeneration of the globus pallidus, substantia nigra and the subthalamic nucleus. He was diagnosed as probable PSP with predominant parkinsonism. Two years later he started to show signs suggestive of cognitive decline, social disinhibition, lack of motivation, loss of empathy, personality changes, visual hallucinations with worsening of previous symptoms. One month later he died due to bronchial aspiration pneumonia.

Patient 2A 71-year-old female with no family history of neurodegenerative diseases, not exposure to toxicants (pesticides). At the age of 62 she began with falls (usually to the right) up to four times a year, difficulties with gait initiation, bradykinesia, non-axial dystonia, right hand rest tremor, without any cognitive decline. Four years later micrographia, parkinsonian facies, back pain and axial rigidity, bradylalia, dysarthria and dysphagia added to the clinical picture. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease plus Parkinson's disease and started treatment with citicoline and levodopa/carbidopa. Two years later, she developed hypoesthesia, stiffness of the lower limbs, freezing of gait, generalized weakness, personality changes, social disinhibition, apathy, loss of empathy. A brain MRI was performed, sagittal plane of T2-weighted showed moderate mesencephalic atrophy along with loss of superior convexity near the protuberance (Hummingbird sign). She was diagnosed as suggestive of PSP with predominant parkinsonism, she continued treatment with levodopa/carbidopa, and 3 years later died of pneumonia.

Patient 3An 85-year-old male, with a family history of a mother who died of hemorrhagic stroke, a brother with unspecified brain cancer and a sister diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. He had a personal history of hypertension and prostate cancer. The later led to chemotherapy and radical prostatectomy at age 76, leaving as a complication urinary incontinence. He began at age of 75 years with multiple falls. By the age of 80 years, falls were periodic and dysphagia, hypophonia, bradykinesia, micrographia to agraphia, back pain, axial rigidity, and slowness of gait were added. One year later he developed parkinsonian facies, difficulties with the initiation of walking and freezing of gait. He was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and started treatment with levodopa/benserazide and pramipexole. Nevertheless, two years later he develop limitation of the range of voluntary gaze in the vertical, along with a worsening on handwriting and speech difficulties, loss of sensitivity, generalized weakness, stiffness of the lower limbs, visual hallucinations, social disinhibition, absence of motivation and loss of empathy along personality changes. A Brain MRI was performed. T2-weighted showed the Hummingbird sign and the diagnosis was changed to PSP. Later he developed severe dysphagia leading to broncho-aspiration and pneumonia.

Patient 4A 73-year-old female, without relevant family history. She had a medical history of morbid obesity with gastric bypass placement and mild pulmonary hypertension without treatment. She started at age of 60 with repetitive falls related to daily life activities, abnormal gait described as lurching and unexplained falls asymmetrically backwards without loss of consciousness. At age 63 she developed bradykinesia, cognitive dysfunction, gait apraxia, postural instability, hypomimia, stiffness of the lowers limbs as well as urinary incontinence. She was diagnosed with Hakim Adams syndrome and peritoneal ventricle bypass valve was placed with partial improvement, leading to a change in diagnosis to Parkinson's disease. Levodopa/carbidopa was started and a brain MRI was performed. Sagittal plane of T2-weighted showed Hummingbird sign, and was then diagnosed as suggestive PSP with predominant parkinsonism., Sever dysphagia was added to the clinical picture, leading to gastrostomy. Due to recurrent pneumonia, a tracheotomy was placed. She later died from bronchoaspiration pneumonia.

ResultsAll of the patients had an initial PD diagnosis, nevertheless due to a torpid clinical course; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed demonstrating midbrain atrophy in the four cases which is highly suggestive of PSP, thus the diagnosis of PSP was established in all patients; still, no neuropathological study was performed after demises.

DiscussionPSP is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by supranuclear gaze paralysis, parkinsonism, behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms. PSP is more frequent in men than in women and the mean age of onset is approximately 63 years.4 PSP must be differentiated from other forms of parkinsonism, mainly PD.

Mutation in the MAPT gene, responsible for coding the production of microtubules associated with TAU protein on chromosome 17q21 is associated with different primary tauopathies including PSP. An abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau and an increased aggregation of this protein are present in tauopathies, although, these disorders are differentiated by their spectrum of symptoms. The absence of gross atrophy and the distribution and type of pathological hallmarks (tangle formation, tufted astrocytes in the basal ganglia, amygdala, and motor cortices, and absence of neuritic plaques) are consistent with a diagnosis of PSP.5–7,18 Motor disorders could present due to a dysfunction of dopaminergic striatal transmission and a final increase of thalamic inhibitory action on motor cortex. Pallidal, putaminal, and subthalamic lesions could be responsible for the absence of response to levodopa. Ocular motility disorders have a more complex origin, with an involvement of both GABAergic and dopaminergic pathways. Movement disorders are caused by lesions of the dorsolateral frontal cortex, prefrontal motor cortex and the dorsolateral part of the caudate nucleus, whereas behavioral disorders (apathy and disinhibition) seem to be caused by frontal cortex lesions. The cognitive deficit in PSP is widespread as shown by the profound deficits obtained in sustained and divided attention tests.4,5,19

Diagnostic criteria include: Sporadic occurrence, gradual progression of PSP-related symptoms, onset age 40 or later, any new onset of neurological, cognitive or behavioral deficit that subsequently progresses during the clinical course in absence of other identifiable cause as a PSP-related symptom. In addition, there are several mandatory exclusion context dependent exclusion criteria (red flags) (see Table 1). Specific combinations of these features lead to three degrees of diagnostic certainty (probable PSP, possible PSP, and suggestive of PSP).9

Show the diagnostic criteria for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy 2017.

| Mandatory inclusion criteria | Mandatory exclusion criteriaa |

|---|---|

| 1. Sporadic occurrenced | Clinical findings |

| 2. Age 40 or older at onsete of first PSP-related symptomf | 1. Predominant, otherwise unexplained impairment of episodic memory, suggestive of AD |

| 3. Gradual progression of PSP-related symptomsf | 2. Predominant, otherwise unexplained autonomic failure, e.g., orthostatic hypotension (orthostatic reduction in blood pressure after 3min standing 30mmHg systolic or 15mmHg diastolic), suggestive of multiple system atrophy or Lewy body disease |

| 3. Predominant, otherwise unexplained visual hallucinations or fluctuations in alertness, suggestive of dementia with Lewy bodies | |

| 4. Predominant, otherwise unexplained multisegmental upper and lower motor neuron signs, suggestive of motor neuron disease (pure upper motor neuron signs are not an exclusion criterion) | |

| 5. Sudden onset or step-wise or rapid progression of symptoms, in conjunction with corresponding imaging or laboratory findings, suggestive of vascular etiology, autoimmune encephalitis, metabolic encephalopathies, or prion disease | |

| 6. History of encephalitis | |

| 7. Prominent appendicular ataxia | |

| 8. Identifiable cause of postural instability, e.g., primary sensory deficit, vestibular dysfunction, severe spasticity, or lower motor neuron syndrome | |

| Imaging findings | |

| 1. Severe leukoencephalopathy, evidenced by cerebral imaging | |

| 2. Relevant structural abnormality, e.g., normal pressure or obstructive hydrocephalus; basal ganglia, diencephalic, mesencephalic, pontine or medullary infarctions, hemorrhages, hypoxic-ischemic lesions, tumors, or malformations | |

| Context dependent exclusion criteriab |

|---|

| Imaging findings |

| 1. In syndromes with sudden onset or step-wise progression, exclude stroke, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) or severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy, evidenced by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), fluid attenuated inversion recovery, or T2*-MRI |

| 2. In cases with very rapid progression, exclude cortical and subcortical hyperintensities on DWI-MRI suggestive of prion disease |

| Laboratory findings |

| 1. In patients with PSP-CBS, exclude primary AD pathology (typical CSF constellation [i.e., both elevated total tau/phospho-tau protein and reduced b-amyloid 42] or pathological b-amyloid PET imaging) |

| 2. In patients aged <45 years, exclude |

| a. Wilson's disease (e.g., reduced serum ceruloplasmin, reduced total serum copper, increased copper in 24h urine, and Kayser–Fleischer corneal ring) |

| b. Niemann–Pick disease, type C (e.g., plasma cholestan-3β,5a,6β-triol level, filipin test on skin fibroblasts) |

| c. Hypoparathyroidism |

| d. Neuroacanthocytosis (e.g., Bassen–Kornzweig, Levine Critchley, McLeod disease) |

| e. Neurosyphilis |

| 3. In rapidly progressive patients, exclude |

| a. Prion disease (e.g., elevated 14-3-3, neuron-specific enolase, very high total tau protein [>1200pg/mL], or positive real-time quaking-induced conversion in CSF) |

| b. Paraneoplastic encephalitis (e.g., anti-Ma1, Ma2 antibodies) |

| 4. In patients with suggestive features (i.e., gastrointestinal symptoms, arthralgias, fever, younger age, and atypical neurological features such as myorhythmia), exclude Whipple's disease (e.g., T. Whipplei DNA polymerase chain reaction in CSF) |

| Genetic findingsc |

| 1. MAPT rare variants (mutations) are no exclusion criterion, but their presence defines inherited, as opposed to sporadic PSP |

| 2. MAPT H2 haplotype homozygosity is not an exclusion criterion, but renders the diagnosis unlikely. |

| 3. LRRK2 and Parkin rare variants have been observed in patients with autopsy confirmed PSP, but their causal relationship is unclear so far |

| 4. Known rare variants in other genes are exclusion criteria, because they may mimic aspects of PSP clinically, but differ neuropathologically; these include |

| a. Non-MAPT associated frontotemporal dementia (e.g., C9orf72, GRN, FUS, TARDBP, VCP, CHMP2B). b. PD (e.g., SYNJ1, GBA). c. AD (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2). d. Niemann–Pick disease, type C (NPC1, NPC2). e. Kufor–Rakeb syndrome (ATP13A2). f. Perry syndrome (DCTN1). g. Mitochondrial diseases (POLG, mitochondrial rare variants). h. Dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy (ATN1). i. Prion-related diseases (PRNP). j. Huntington's disease (HTT). k. Spinocerebellar ataxia (ATXN1, 2, 3, 7, 17) |

Perform genetic counseling and testing, if at least one first- or second-degree relative has a PSP-like syndrome with a Mendelian inheritance trait or known rare variants; high-risk families may be identified as described elsewhere49; the list of genes proposed reflects current knowledge and will evolve with time.

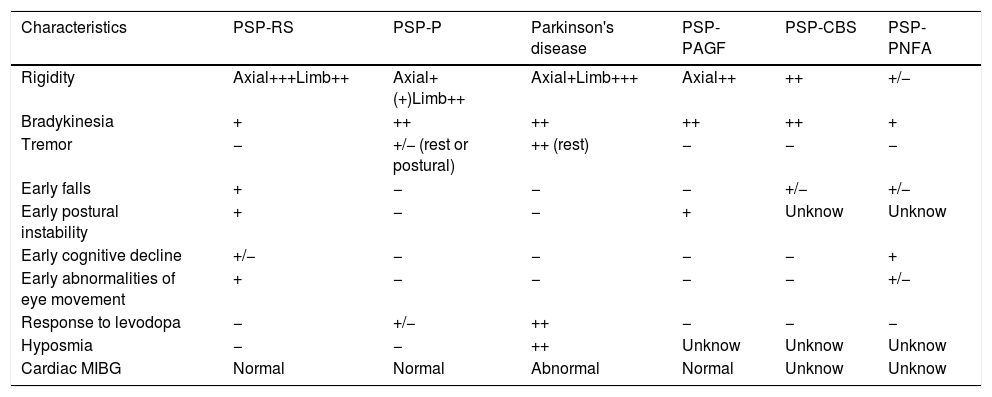

There are progressive supranuclear palsy variants with different characteristics12–17 (see Table 2).

Progressive supranuclear palsy variants.

| Characteristics | PSP-RS | PSP-P | Parkinson's disease | PSP-PAGF | PSP-CBS | PSP-PNFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigidity | Axial+++Limb++ | Axial+(+)Limb++ | Axial+Limb+++ | Axial++ | ++ | +/− |

| Bradykinesia | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Tremor | − | +/− (rest or postural) | ++ (rest) | − | − | − |

| Early falls | + | − | − | − | +/− | +/− |

| Early postural instability | + | − | − | + | Unknow | Unknow |

| Early cognitive decline | +/− | − | − | − | − | + |

| Early abnormalities of eye movement | + | − | − | − | − | +/− |

| Response to levodopa | − | +/− | ++ | − | − | − |

| Hyposmia | − | − | ++ | Unknow | Unknow | Unknow |

| Cardiac MIBG | Normal | Normal | Abnormal | Normal | Unknow | Unknow |

PSP=progressive supranuclear palsy; RS=Richardson's syndrome; P=Parkinsonism; CBS=corticobasal syndrome; PAGF=pure akinesia with gait freezing; PNFA=progressive non-fluent aphasia; MIGB=131I-labeled meta-iodobenzylguanidine.

In the initial approach of the patient with suspected Parkinson's disease with clinic of bradykinesia and at least one of the following symptoms and signs (muscle stiffness, resting tremor of 4–6Hz and postural instability not caused by primary visual dysfunction, vestibular, cerebellar or proprioceptive), it is necessary to determine the existence of red flags, for example: (acute onset, onset or rapid progression to asymmetry in one year, postural instability or prominent dementia during the first year of diagnosis, abrupt gait (“freezing of the gait”), low or no response to levodopa, hallucinations in the absence of hallucinogenic drugs, early and severe dysautonomia, early diplopia, gaze microscopes, paraplegia apraxia, fascia reptileana, paralysis of the vertical gaze, abnormal movements other than tremor (myoclonic tremor, reflex myoclonus), snoring stiff breathing, frequent cramps, polylalia, polylogy, echolalia, cold hands, dysarthria, coordination disorders, gait apraxia with increase of the base of support), the continuous approach to an atypical parkinsonism such as infectious, traumatic, iatrogenic, hereditary, and sporadic (multisystemic atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, atypical Parkinson's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy).20–25

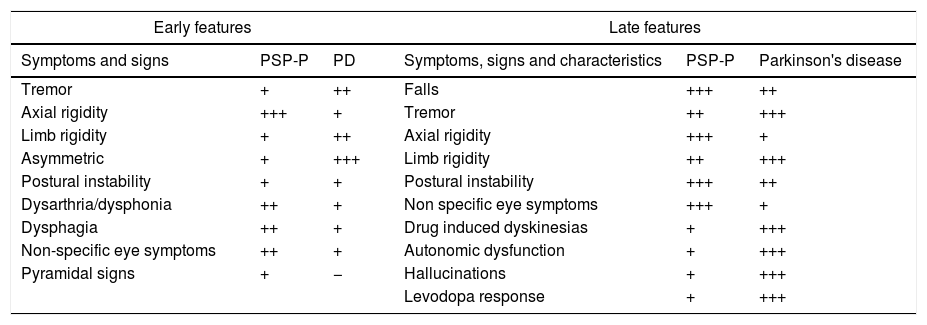

The onset of PSP typically occurs with a prevailing proximal axial muscle rigidity, which causes head and trunk hyperextension [symmetric rigid-akinetic syndrome, and an early instability of balance with frequent falls (especially backward)]. Parkinson's disease is characterized by bending forward. The characteristic sign of PSP is the supranuclear palsy of vertical gaze followed by abnormalities of horizontal gaze. This sign, rarely present at the onset of the disease, usually appears after 3 or 4 years and is absent in very few patients. The disorder begins with a slowing of vertical saccade movements (rapid eye movements) followed by alterations of downward gaze and a complete palsy of vertical gaze. Pursuit movements (slow ocular movements) can be relatively preserved, especially at the beginning of the disease, and in Parkinson's disease are almost normal. Speech and swallowing problems are much more common and serious in progressive supranuclear palsy than in Parkinson's disease, and they tend to appear earlier in the course of the disease4,26,27 (see Table 3).

Early and late features in progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson's disease.

| Early features | Late features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms and signs | PSP-P | PD | Symptoms, signs and characteristics | PSP-P | Parkinson's disease |

| Tremor | + | ++ | Falls | +++ | ++ |

| Axial rigidity | +++ | + | Tremor | ++ | +++ |

| Limb rigidity | + | ++ | Axial rigidity | +++ | + |

| Asymmetric | + | +++ | Limb rigidity | ++ | +++ |

| Postural instability | + | + | Postural instability | +++ | ++ |

| Dysarthria/dysphonia | ++ | + | Non specific eye symptoms | +++ | + |

| Dysphagia | ++ | + | Drug induced dyskinesias | + | +++ |

| Non-specific eye symptoms | ++ | + | Autonomic dysfunction | + | +++ |

| Pyramidal signs | + | − | Hallucinations | + | +++ |

| Levodopa response | + | +++ | |||

Among the most important clinical features with which our patients began were: Gait abnormalities and falls, bradykinesia, later presented slowness of gait, micrographia, back pain and nuchal rigidity, parkinsonian facies, bradylalia, dysphagia and hypophonia and ended with social disinhibition, and it is suggested that a patient with a high suspicion of progressive supranuclear palsy should be asked to ask directed questions about these clinical symptoms and red flags. It is important to adequately evaluate patients with early falls, their evolution and their characteristics as well as to perform an adequate exploration of eye movements, in addition to taking into consideration the neuropsychiatric symptomatology and its temporality, since they allow an early suspicion of paralysis supranuclear and an early approach.

The MRI usually shows midbrain atrophy, and sagittal sections are particularly useful to demonstrate the thinning of the quadrigeminal plate, which is more marked rostrally. Atrophy and dilatation of the third ventricle are present in PSP patients. The “hummingbird” sign (atrophy of dorsal midbrain resembles hummingbird's head and bill in midsagittal plane, the “morning glory” sign (concavity of the lateral margin of the midbrain tegmentum in axial planes, Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity values are typically high (>90%) for differentiating PSP-RS from controls and from MSA and PD using midbrain area. T2-weighted images sometimes show putaminal and/or basal ganglia hyperintensity, suggesting gliosis, and ischemic lesions; a slight increase in signal intensity may be present in the periaqueductal region, suggesting the presence of gliosis. In proton density-weighted images, a decrease of the signal intensity in the superior cerebellar peduncle can be present, representing a sign of demyelination and gliosis.28–30 In three of the four cases, MRI was performed several years after the initial diagnosis of PD was made. While structural MRI does not have a role in confirming the diagnosis of PD, its usefulness in ruling-out other differential diagnosis such as vascular parkinsonism, brain tumors and hydrocephalus should not be forgotten. In addition, as mentioned before there are some signs that may be present suggesting other atypical parkinsonisms such as PSP or even multiple system atrophy. In our patients were found in the Cranial MRI, the characteristics mentioned above, however it is important to mention that not all PSPs have a hummingbird sign with a sensitivity of 68.4 and specificity of 100 and not all hummingbird signs are PSP (e.g. fragile X), etc. Initially, all patients were diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and by the presence of red flags subsequently granted some variant of progressive supranuclear palsy. The patient 1 was PSP-Pallido-nigro-lusyan degeneration and axonal atrophy (PSP-PNLA) because the initial characteristics clinical was gait abnormalities and falls asymmetrical, micrographia and bradykinesia. The patient 2 was PSP-Parkinsonism (PSP-P) Plus Alzheimer's disease because the initial characteristics clinical was falls in initial asymmetrical, presence of tremor, bradykinesia non axial dystonia, difficulties with the initiation of walking, accompanied by neurological deterioration. The patient 3 was PSP-Pure akinesia with gait freezing (PSP-PAGF) because the characteristics clinical were falls in initial asymmetrical, features of micrographia, hypophonia and slowness of gait. The patient 4 was PSP-Richardson's syndrome (PSP-RS) plus Hakim Adams syndrome because the characteristics clinical was abnormal gait described as lurching and unexplained falls asymmetrical backwards without loss of consciousness, following cognitive dysfunction, urinary incontinence, gait apraxia and hydrocephalus.

Single photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) studies have reported a marked reduction of frontal and basal ganglia perfusion. Positron emission tomography (PET) with 2-fluoro-deoxyglucose in PSP patients has shown a global reduction of cortical glucose metabolism, specifically in the medial and lateral frontal gyri, basal ganglia, and midbrain. PET has shown a reduction of dopaminergic terminals, as labeled by (18F)-fluoro DOPA, both in the caudate and in the putamen; this contrasts with neuroradiological findings in PD, where dopaminergic terminals are more compromised in the putamen terminals than in the caudate nucleus.2,30,31

An effective pharmacological intervention for PSP is not available. l-DOPA therapy improves rigid akinetic symptoms in about 10% of patients, however this efficacy is just for about 2 years or less. PSP patients, however, do not suffer from the motor and psychic side effects of dopaminergic drugs, therefore l-DOPA therapy is recommended (up to 2g/day), despite its low efficacy. Dopamine agonist does not offer any advantage compared to l-DOPA. Amitriptyline and amantadine can improve some PSP symptoms, potential clinical benefit, particularly with regard to improvements in apathy and locomotion. But anticholinergic effects can damage cognitive function and ambulation, and their use must be limited only to few particular indications (e.g. hypersalivation).32,33 In two cases the dose of levodopa was titrated and clinical improvement was achieved, however in two patients, so its evolution was torpid. In all cases levodopa was started from the diagnosis.

Neither noradrenergic drugs nor cholinergic replacement therapy with donepezil, a centrally acting cholinesterase inhibitor, is likely to improve PSP symptoms, positive effects on memory but decreased motor function. The GABAergic drug zolpidem produces some improvement of motor symptoms, dysarthria, and ocular abnormalities according to anecdotal evidence from case reports.34 Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are effective at treating depression, obsessive-compulsive behavior and emotional lability but may worsen apathy. Some studies with neurotrophic drugs, free radical scavengers and anti-inflammatory drugs have been performed for memory. Physiokinesy therapy, logopedic, and ergotherapy may have an important role in motor function. Other symptomatic palliative therapies are botulin toxin injections for the blepharospasm and levator palpebrae inhibition, oxybutynin for the hyperreflexia of detrusor muscle, and antidepressants for emotional incontinence.4,11,30

The mean survival in recent studies has reported an average survival of 5–8 years. The most common causes of death in this group of patients are: primary neurogenic respiratory insufficiency or pulmonary embolism, and bronchial aspiration so you should consider tracheostomy and gastrostomy before it happens.4,27,35 In our series of cases, survival was 9–10 years and mortality was associated with bronchial aspiration pneumonia. Due to the poor evolution, all of them required palliative therapies and had a tracheostomy and gastrostomy by the high risk of bronchial aspiration.

ConclusionThe progressive supranuclear palsy should be considered after an initial approach to Parkinson's disease with red flags and subsequently according to clinical characteristics and patient evolution can be subclassified to the specific PSP type. The resulting dysfunction of dopaminergic, GABAergic, cholinergic, and noradrenergic pathways causes the symptoms of PSP. Moreover, PSP has to be differentiated from the following atypical parkinsonisms: multisystemic atrophy, Lewy body disease, etc. The neuroradiological exams (MRI, SPECT, and PET) can be useful for diagnosis of PSP. Treatment with levodopa, especially in patients with a more parkinsonian phenotype, should be considered.

Patient's data protectionWe declare to have used Médica Sur's protocols to access to the patient's data and the information was obtain with the unique purpose of the scientific investigation and scientific disclosure.

FundingThis work was performed in “Médica Sur Clinic & Foundation”. The present investigation has not received any specific scholarship from the agencies of the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflict of interests or something to disclose.