The aim of the present study is to describe the pattern of suicide deaths in the region of Osona (Barcelona) during the period 2013–2015, and to analyse the use of the Psychological Autopsy (PA) method.

Material and methodsIt is a retrospective design using the suicide deaths register (n=31). The PA sample (n=14) was composed of adult relatives and close friends, recruited from the Consorci Hospitalari de Vic. The PA method was performed using the Semi-Structured Interview for Psychological Autopsy (SSIPA), adapted and validated to the Spanish language (García-Caballero et al., 2010).

ResultsThe main profile was of a male, married, with no psychiatric history, and used methods like hanging or being running over by a train. In the sub-sample on which the PA was carried out, it was observed that the main precipitating or motivating factors were those related to social, family, and health problems. The prevalence of diagnosed psychopathologies was not a majority profile, but vulnerable personality traits were found. As most of the cases showed previous preparations and verbalisations regarding their intention, it can be concluded that the decision was not impulsive but deliberate.

ConclusionsThe PA method is an efficient tool to describe and obtain data about suicide that may be relevant and useful in the design and implementation of prevention programmes. Moreover, it may help to perceive the individual characteristics of each region promoting a better adjustment and individualisation of these programmes.

El objetivo del presente estudio es describir el perfil de las muertes por suicidio en la comarca de Osona (Barcelona) durante el período 2013–2015 y analizar la aplicación de la técnica autopsia psicológica (AP).

Material y métodosEl diseño es retrospectivo a partir del registro de suicidios (n=31). La muestra de la AP (n=14) estuvo formada por familiares y personas adultas próximas al fallecido, reclutadas a través del registro del Consorci Hospitalari de Vic. Se utilizó el método de la AP mediante la Semi-Structured Interview for Psychological Autopsy (SSIPA), una entrevista semiestructurada adaptada y validada al español (García-Caballero et al., 2010).

ResultadosEl perfil mayoritario de las muertes por suicidio corresponde a varones, casados, sin antecedentes psiquiátricos que utilizaron métodos como el ahorcamiento o el arrollamiento por tren. En la submuestra en que se realizó la AP se observa que los factores precipitantes o motivadores están relacionados con problemas a nivel social, familiar y de salud. La prevalencia de psicopatologías diagnosticadas no fue mayoritaria, pero se detectaron rasgos de personalidad vulnerables. En muchos casos hubo preparativos y verbalizaciones previas respecto a sus intenciones, por lo que se deduce que la decisión fue tomada de forma premeditada y no impulsiva.

ConclusionesLa AP representa una herramienta eficaz para la obtención de datos relativos al suicidio que pueden ser relevantes y útiles en el diseño y la implementación de programas de prevención, ayudando a detectar la idiosincrasia particular de cada región y permitiendo una mayor adaptación e individualización de dichos programas.

Suicide, understood as the voluntary action of taking one's own life, is the second most common cause of violent death among individuals between 15 and 29years of age worldwide, and the fifth most common among individuals aged between 30 and 49, constituting a major public health problem, as it accounts for more deaths per year than homicides, deaths in armed conflicts and road accidents.1 According to the data presented by the World Health Organisation,2 the suicide death rate globally is 11.4 per 100,000 inhabitants (15 males/8 females). The rate in Europe is slightly higher, at 11.6 per 100,000 inhabitants, probably owing to the more thorough recording thereof.3 Spain is in 30th position among the 36 European countries studied, being one of the geographic areas in Europe with the lowest suicide rate, at 8.41.4 Finally, the rate in Catalonia is 7.06, accounting for 13.6% of the total number of suicides in Spain5; and, specifically in Osona, the region in which this study is conducted, a rate of 9.56 is observed.

The phenomenon of suicide and its high frequency across the world has led many countries to address this situation on 2 different levels; on one hand, by establishing healthcare policies aimed at prevention and the reduction of the suicide rate; and, on the other, by focusing on raising awareness of the non-stigmatisation of the problem through mental health information and promotional campaigns. The detection and description of the risk factors, the precipitating factors, as well as the protective factors, comprise a primary objective in the prevention of suicide globally.2 Interest in the study and in-depth understanding of the causes surrounding a suicide has fostered the design of different research tools, one of which is psychological autopsy (PA).

The concept of PA was coined by Edwin Shneidman, an American psychologist and co-founder of the American Association of Suicidology.7 It is a post-mortem research tool designed to retrospectively analyse the profile of the death by suicide. It consists of gathering, describing and analysing all the information on the events surrounding a suicide: medical certificates and examinations, forensic reports, clinical history, personal documents, letters, notes and, in particular, the information provided through interviews with family members and close friends.8 Initially, its main function was to shed light on and help clarify what we know as suspicious deaths, to allow the NASH (Natural, Accidental, Suicide, Homicide) code to be applied in the death certificate.9 As it was used, this function evolved gradually and the technique was perfected, and it began to shed light on other types of variables, such as precipitating factors and stressors, as well as the patient's mental state in the period prior to committing suicide. More recently, a therapeutic function in the grieving process of family and close friends has been observed; this is an important fact as, according to the World Health Organisation,10 each case of suicide directly affects around 6 individuals close to the deceased.

There are different methodologies for applying PA.11–15 Some of the most widely used instruments are the Modelo de Autopsia Psicológica Integrado [Integrated Psychological Autopsy Model], MAPI-I for suicides and MAPI-II for homicides16 and the Semi-Structured Interview for Psychological Autopsy (SSIPA)17 adapted and validated for Spanish by García-Caballero et al.8

In Spain, the use of PA for the analysis of deaths by suicide is limited and there are scant studies in this regard,8,18 despite the usefulness thereof having been demonstrated on informative, preventative and treatment levels. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, in Catalonia no study has been published on PA. Thus, the aim of this study is to describe and analyse deaths by suicide in the region of Osona (Barcelona) during the period 2013–2015, by means of applying the PA technique.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis work is a cross-sectional observational study by means of which a record was made of all suicide deaths occurring in the region of Osona during the period 2013–2015 using statistical data originating from the official record and the use of the PA technique.

The records were obtained from the Vic Hospital Consortium, which has a framework partnership agreement with the Department of Justice, and more specifically with the Institute of Legal Medicine.19

SampleThe total number of cases recorded was 31 suicide deaths, on which the socio-demographic data and basic death-related statistics were obtained. Of the total number of cases, PA was performed on 14, after obtaining consent from a family member to do so.

The inclusion criteria established for PA were as follows: (a) being a first-degree family member or close friend of the deceased, (b) being of legal age and (c) having no learning disability.

Participation in the study was voluntary, subject to signature of the informed consent. Data confidentiality was guaranteed, pursuant to Organic Law 15/1999 on the Protection of Personal Data.

MethodThe instrument used to conduct the PA was the SSIPA,17 translated into and validated in Spanish.8

The SSIPA collects the following data. Firstly, the socio-demographic data on the circumstances of the death and on the interviewed party. Secondly, data relating to the type of relationship between the family member and the deceased and a family genogram. Finally, relevant information related to the death, structured into 4 main modules. The first evaluates the precipitating factors and stressors which may have played a role in the suicide. The second assesses the patient's motivation for committing suicide, on the basis of recent psychosocial and environmental problems or life events; the symptoms of malfunctioning; personality characteristics or traits, and events associated with family life. The third evaluates lethality, the method used and the probability of death. Lastly, the fourth refers to intentionality and planning.

The PA concludes with a decision algorithm for each of the modules, plus one of a global nature in which, taking into account the responses recorded during the interview, a conclusion is reached as to whether the information obtained suggests suicide or if, on the contrary, there is a high probability of unintentional death.

ProcedureFirstly, the reference hospital provided us with the data relating to the total number of suicide deaths. The primary healthcare physicians were then contacted to notify them of the project and to establish contact with the deceased's family. After establishing initial telephone contact with family members and requesting their voluntary participation, a date, time and location was set for conducting the interview. In all cases, the contact and the interview took place between the third and sixth month after suicide, with the aim of avoiding the initial moments of bereavement, but without allowing too much time to pass with a view to preserving clarity of memory. All interviews were conducted by a clinical psychologist experienced in handling situations of bereavement and trained in the PA method.

Statistical analysis of dataData analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; version 23.0; Inc., Chicago, Illinois). To present the descriptive data, means and standard deviations were used for the continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were employed for the categorical variables.

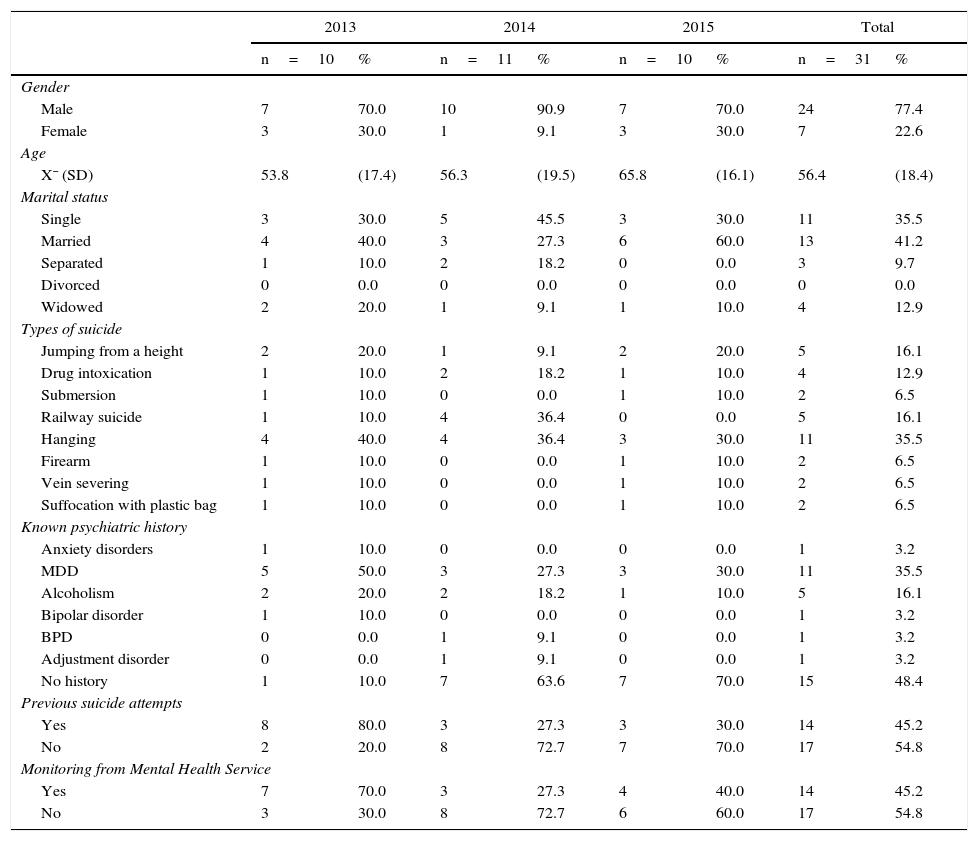

ResultsSocio-demographic and descriptive data on the total number of suicide deathsThe data relating to the total number of suicide deaths (n=31) can be consulted in Table 1. It can be seen that the number of cases is stable, averaging around 10 cases per year, with a higher prevalence in males (77.4%). In relation to marital status, the highest rate is found among married individuals (41.9%) with a lower rate among separated individuals (9.7%) and divorcees (0%). The most common methodology is hanging (35.5%), followed by jumping from a height (16.1%), railway suicide (16.1%) and drug intoxication (12.9%).

Socio-demographic and descriptive data on the total number of suicide deaths in Osona during the period 2013–2015 (n=31).

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=10 | % | n=11 | % | n=10 | % | n=31 | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 7 | 70.0 | 10 | 90.9 | 7 | 70.0 | 24 | 77.4 |

| Female | 3 | 30.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 3 | 30.0 | 7 | 22.6 |

| Age | ||||||||

| X¯ (SD) | 53.8 | (17.4) | 56.3 | (19.5) | 65.8 | (16.1) | 56.4 | (18.4) |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 3 | 30.0 | 5 | 45.5 | 3 | 30.0 | 11 | 35.5 |

| Married | 4 | 40.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 6 | 60.0 | 13 | 41.2 |

| Separated | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.7 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Widowed | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 10.0 | 4 | 12.9 |

| Types of suicide | ||||||||

| Jumping from a height | 2 | 20.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 20.0 | 5 | 16.1 |

| Drug intoxication | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 4 | 12.9 |

| Submersion | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Railway suicide | 1 | 10.0 | 4 | 36.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 16.1 |

| Hanging | 4 | 40.0 | 4 | 36.4 | 3 | 30.0 | 11 | 35.5 |

| Firearm | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Vein severing | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Suffocation with plastic bag | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 6.5 |

| Known psychiatric history | ||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 |

| MDD | 5 | 50.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 11 | 35.5 |

| Alcoholism | 2 | 20.0 | 2 | 18.2 | 1 | 10.0 | 5 | 16.1 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 |

| BPD | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 |

| Adjustment disorder | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.2 |

| No history | 1 | 10.0 | 7 | 63.6 | 7 | 70.0 | 15 | 48.4 |

| Previous suicide attempts | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 80.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 3 | 30.0 | 14 | 45.2 |

| No | 2 | 20.0 | 8 | 72.7 | 7 | 70.0 | 17 | 54.8 |

| Monitoring from Mental Health Service | ||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 70.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 4 | 40.0 | 14 | 45.2 |

| No | 3 | 30.0 | 8 | 72.7 | 6 | 60.0 | 17 | 54.8 |

BPD, borderline personality disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; n: sample size; SD, standard deviation; X¯, mean.

With regard to psychiatric history, it should be stressed that 48.4% of subjects presented no type of known history, whilst the most common disorder associated with suicide was major depressive disorder (MDD; 35.5%), followed by alcoholism (16.1%). Other disorders, such as borderline personality disorder (BPD) or anxiety disorders, had a lower prevalence (3.2% in both cases). In 45.2% of cases, there had been a previous suicide attempt; and, at the same percentage (45.2%), some type of control or follow-up had been carried out by the public mental health services. In the remaining 54.8% of cases, no type of monitoring was carried out in the mental health departments of the Vic Hospital Consortium, although it is not known whether there was any type of private follow-up.

Data relating to the sub-sample in which the psychological autopsy was conductedData relating to the sub-sample (n=14) in which the PA was conducted are presented ordered on the basis of the 4 modules examined by the PA, and with a final section devoted to the decision algorithms. 92.9% of the PAs were conducted on close relatives and 7.1% on close friends of the victim.

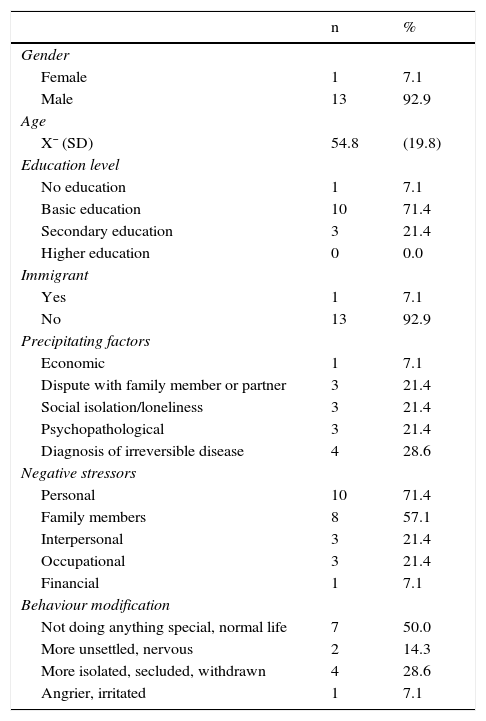

Precipitating factors and stressors92.9% of those subjects who committed suicide were male, principally with a basic educational level (71.4%), from Catalonia and/or Spain (92.9%).

The factors which could precipitate the decision to commit suicide (Table 2) include the diagnosis of an irreversible disease (28.6%), a dispute with a family member or partner (21.4%), social isolation (21.4%) and the presence of some type of psychopathology (21.4%). Some examples reported by family members are the death of a pet, the diagnosis of bladder cancer or the breakup of a relationship, while stressors immediately prior to the act include mainly personal factors (71.4%) and family factors (57.1%), such as sexual dysfunction or infidelity. In both categories, it can be seen that financial factors are not perceived as being precipitating factors or stressors (7.1%), although this does not mean that there were not any.

Precipitating factors and stressors on the basis of psychological autopsy (n=14).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1 | 7.1 |

| Male | 13 | 92.9 |

| Age | ||

| X¯ (SD) | 54.8 | (19.8) |

| Education level | ||

| No education | 1 | 7.1 |

| Basic education | 10 | 71.4 |

| Secondary education | 3 | 21.4 |

| Higher education | 0 | 0.0 |

| Immigrant | ||

| Yes | 1 | 7.1 |

| No | 13 | 92.9 |

| Precipitating factors | ||

| Economic | 1 | 7.1 |

| Dispute with family member or partner | 3 | 21.4 |

| Social isolation/loneliness | 3 | 21.4 |

| Psychopathological | 3 | 21.4 |

| Diagnosis of irreversible disease | 4 | 28.6 |

| Negative stressors | ||

| Personal | 10 | 71.4 |

| Family members | 8 | 57.1 |

| Interpersonal | 3 | 21.4 |

| Occupational | 3 | 21.4 |

| Financial | 1 | 7.1 |

| Behaviour modification | ||

| Not doing anything special, normal life | 7 | 50.0 |

| More unsettled, nervous | 2 | 14.3 |

| More isolated, secluded, withdrawn | 4 | 28.6 |

| Angrier, irritated | 1 | 7.1 |

SD, standard deviation; n, sample size.

Finally, it should be noted that 50% of those interviewed did not refer to any type of modification in the subject's behaviour habits, or any relevant change in the period prior to the suicide; while the other half referred to the subject being more insular or withdrawn, unsettled or nervous, and angry or irritated.

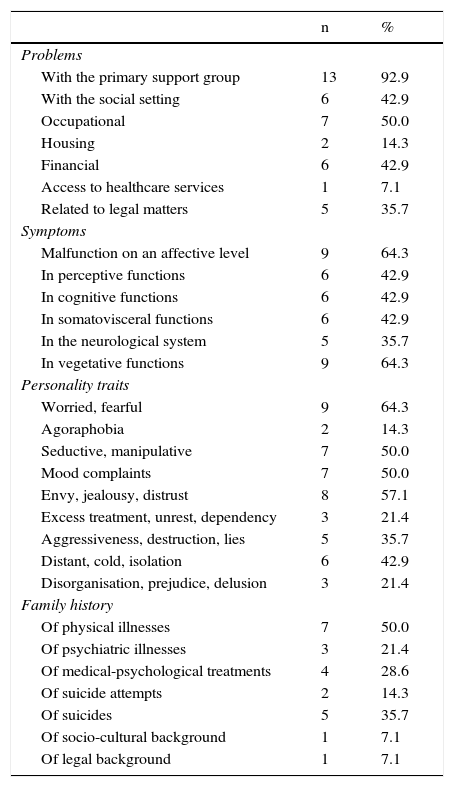

Motivating factorsThe motivating factors are divided into 4 sub-categories: problems, symptoms, personality traits and family history (Table 3).

Motivating factors on the basis of psychological autopsy (n=14).

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Problems | ||

| With the primary support group | 13 | 92.9 |

| With the social setting | 6 | 42.9 |

| Occupational | 7 | 50.0 |

| Housing | 2 | 14.3 |

| Financial | 6 | 42.9 |

| Access to healthcare services | 1 | 7.1 |

| Related to legal matters | 5 | 35.7 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Malfunction on an affective level | 9 | 64.3 |

| In perceptive functions | 6 | 42.9 |

| In cognitive functions | 6 | 42.9 |

| In somatovisceral functions | 6 | 42.9 |

| In the neurological system | 5 | 35.7 |

| In vegetative functions | 9 | 64.3 |

| Personality traits | ||

| Worried, fearful | 9 | 64.3 |

| Agoraphobia | 2 | 14.3 |

| Seductive, manipulative | 7 | 50.0 |

| Mood complaints | 7 | 50.0 |

| Envy, jealousy, distrust | 8 | 57.1 |

| Excess treatment, unrest, dependency | 3 | 21.4 |

| Aggressiveness, destruction, lies | 5 | 35.7 |

| Distant, cold, isolation | 6 | 42.9 |

| Disorganisation, prejudice, delusion | 3 | 21.4 |

| Family history | ||

| Of physical illnesses | 7 | 50.0 |

| Of psychiatric illnesses | 3 | 21.4 |

| Of medical-psychological treatments | 4 | 28.6 |

| Of suicide attempts | 2 | 14.3 |

| Of suicides | 5 | 35.7 |

| Of socio-cultural background | 1 | 7.1 |

| Of legal background | 1 | 7.1 |

n=sample size.

In practically the entire sample, there were problems with the primary support group (92.9%), it being qualified that said support was non-existent, weak or manipulative, and that the existing relationship was cold and distant, tense or very tense. Accordingly, 42.9% exhibited problems with the social setting, highlighting fragility in relationship ties and isolation. Half referred to occupational problems (50%) and financial problems (42.9%), such as multiple fines and tax debts. If we take into account that 7 of the subjects were retired, this means that all of the employed individuals had some type of labour problem or conflict.

Worthy of note in the symptoms category were those of an affective type (64.3%) with symptoms of sadness, desperation, self-reproach and anhedonia, and on the level of vegetative functions (64.3%) with problems of insomnia and nightmares, or digestive distress.

With regard to personality traits, the individuals questioned mainly reported personality traits of worry or fear (64.3%), jealousy or mistrust (57.1%), mood complaints (50%), manipulation (50%) and isolation (42.9%).

Lastly, the interviewees referred to family histories of physical illnesses (50%), such as cancer or stroke, and mental disorders (21.4%), such as MDD or Alzheimer's disease. The family history of suicide attempts was 14.3%, while deaths in the family as a result of suicide rose to 35.7%.

Lethality factorsThe most frequently used methods were hanging (28.6%) railway suicide (28.6%), followed by jumping from a height (14.3%), and submersion (7.1%), use of firearms (7.1%), intoxication (7.1%) and the combined method of intoxication/submersion (7.1%). The location for carrying out the act was predominantly in indoor areas, such as within the individual's own home (57.1%). In almost all cases, the methods were considered easily accessible and conducive to a rapid death.

Intentionality factorsWith regard to intentionality, it was significant that in a number of cases there was prior intentionality (21.4%) and the verbalisation (35.7%) of the wish to die during the past year. Family members stated that the deceased had amassed medicines, bought a rope, had left the flat clean and the fridge empty, or would often say that they were a “burden” and that “the best thing would be for them to die”. It is also important to highlight the verbalisation of death as an only option (14.3%), the verbalisation of death with a manipulative affect (7.1%), the verbalisation of suicide-related premonitions or dreams (7.1%) and the occurrence of multiple accidents or dangerous situations related to death (14.3%), such as, for example, multiple car accidents over a short period of time.

With regard to the planning of death, it can be seen that half of the subjects made prior preparations, such as the purchase of a weapon, a rope or poison (14.3%), or they visited a relative or friend whom they had not visited in some time (21.4%). 28.6% left specific instructions to their family and/or close friends in the event of death, such as, farewell letters (28.6%), recently written wills (21.4%) and gifts or the sharing out of possessions (14.3%). In 71.4% of cases, the subjects had the opportunity to notify or ask for help but did not do so; and in 42.9% of cases, they took specific measures to ensure that they would not be interrupted or saved, such as leaving their mobile phone at home or disconnecting it.

Decision algorithmsFinally, on the basis of the 4 categories of the PA, different decision algorithms were developed in order to be able to conclude whether the death was actually motivated by suicide, or whether other possible causes could be considered. In this study, in 92.8% of the cases, it was concluded that the cause was “highly suspected of being suicide” and only in 7.1% of cases it was concluded that the cause was “fairly suggestive of suicide”.

DiscussionThis study shows the data relating to the total number of suicide deaths (n=31) in the region of Osona in the period 2013–2015, as well as the data relating to PAs performed on family members and close friends in 45.1% of the cases. The most common profile of suicide deaths corresponded to married men with no known psychiatric history, and who employed rapid methods with high levels of lethality, such as hanging or railway suicide. Considering the sub-sample in which the PA was performed, we also observed that the precipitating or motivating factors are generally related to social, family and health problems. Although the prevalence of diagnosed psychopathologies was not predominant, personality traits denoting shortcomings on a relational and affective level were detected. Lastly, it should be mentioned that in many cases there were prior preparations and verbalisations with regard to their intentions, owing to which it follows that the decision was taken in a premeditated manner, and not hastily or impulsively.

Comparing these results with previous data from Osona19 (2006–2011), similar data can be observed with regard to the higher percentage of males (80.72%), the mean age (range 51.3–60.25) and the principal methods, namely hanging and railway suicide. Nonetheless, a slight drop in the number of suicides per year is observed (range 12–17 vs 10–11) along with an increase in the percentage of previous suicide attempts, rising from 26.5% in the period 2006–2011 to 45.2% in the period 2013–2015.19 This may be due to the fact that in 2012 a suicide attempt detection programme was implemented in which the patients attended to for suicide attempts were monitored, and individuals were urged to attend A&E for any type of suicidal ideation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on PA to be conducted in Catalonia, and one of the few conducted in Spain.8,18 In our study, the PA provided important data with regard to the characteristics of death, and the decision algorithms helped us to determine death by suicide.

Generally speaking, there are a number of different risk factors in the decision to commit suicide. According to the Guía práctica clínica de prevención y tratamiento de la conducta suicida [Clinical practice guide for the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour],20 some of the most important are the presence of mental disorders, previous suicide attempts, a physical illness and social–family and environmental factors, such as social support. Nonetheless, these factors display significant variations depending on the different geographical and cultural areas. In Spain, the study by Antón-San-Martín et al.,18 conducted in the region of Antequera-Málaga, identified the predominant risk factors as being male, age range between adulthood and old age, family history of suicide and familial aggregation of mental disorders, a diagnosis of personality disorders, and family conflicts in the month prior to the suicide. Conversely, the study by García-Caballero et al.8 conducted in Ourense found that the majority of suicides were committed by women (57.7%), the majority of whom were single. These data show that, even though there are repetitive patterns in suicidal behaviour, the local specificities of each region need to be identified in order to be able to adapt the different prevention programmes in a more appropriate manner.

On the contrary, if we consider protective factors, it can be observed that one of the most important is social support, mainly from the primary support group.21 In this study, we have observed that, in the majority of cases, this was found to have deteriorated, with an enormous component of social isolation and problems of an affective nature. In general, social isolation has been linked to suicide in a number of studies,22–24 and it is also considered an important risk factor for the development of depression,25 one of the psychopathologies largely associated with suicidal behaviour.26 Social isolation gives rise to a negative bias in social cognition, and may have an effect on an emotional, behavioural and interpersonal level and, consequently, in decision-making.27 For this reason, an important proportion of prevention programmes should focus on improving social support and minimising social isolation, particularly in those groups most vulnerable to affective disorders.

This study has proved useful for the better understanding and insight into the phenomenon of suicide in the region of Osona. However, it does have a number of important limitations, such as the small sample size and the possible biases arising from the methodology employed. Although the family members interviewed represented almost 50% of the cases, it would be desirable to have a higher representation in order to be able to collect the greatest possible quantity of data by adding a third informer. Moreover, voluntary participation in the PA may constitute a bias in itself, owing to the fact that more traumatic or violent cases of death–such as the death of a child, or even the most vulnerable individuals or those with emotional difficulties for processing the bereavement–may be omitted. On the other hand, mention should also be made of the bias inherent to retrospective studies, given that this may result in the effect of searching for elements in the memory evoked by the PA questions themselves.

By way of conclusion, the results of this study have shown that the PA represents an effective tool for describing and obtaining data relating to suicide which may be relevant and useful in the design and implementation of prevention programmes. Furthermore, it is useful for detecting the local specificities of each region, allowing the greater adaptation and individualisation of such programmes. Lastly, the PA provides extremely valuable information regarding the degree of subjective discomfort and the psychiatric and psychological symptomatology of both the deceased and of family members, fostering greater understanding and helping to deal with grief.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors wish to thank all those individuals who have participated in this study.

Please cite this article as: Naudó-Molist J, Arrufat Nebot FX, Sala Matavera I, Milà Villaroel R, Briones-Buixassa L, Jiménez Nuño J. Análisis descriptivo de los suicidios y la aplicación del método autopsia psicológica durante el período 2013–2015 en la comarca de Osona (Barcelona, España). Rev Esp Med Legal. 2017;43:138–145.