To evaluate how the decision regarding limitation of life support treatment (LLST) has varied in a tertiary ICU over a period of ten years.

MethodsAn observational, retrospective and comparative study of ICU patients in a tertiary university hospital in Spain from January 2005 to December 2014. Through the analysis of the unit's computerised database, we obtained the sample of patients in whom LLST was performed in the period described. The categorical variables are described as absolute frequencies and percentages, and the quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation. Chi-square was used to assess the statistical significance of categorical variables and Student's t-test was used for quantitative variables. The relationship between variables and LLST decision was studied using logistic regression.

ResultsLLST was performed in 409 (4.95%) of the 8258 patients studied. The comparative analysis showed significant differences between the APACHE II values on the day of the decision regarding LLST (p=0.0001), there was a change in the distribution of the type of LLST, a change in the health status of patient prior to ICU admission and ICU mortality at different stages. Type I LLST went from the most common type of LLST in 2005 to the least common a decade later (26.06%; 95% CI: 15.60–40.26 versus 7.32%; 95% CI: 2.52–19.43). Type V LLST is currently the second most common option (19.51%; 95% CI: 10.23–34.01) when deciding on LLST.

ConclusionLLST decisions have changed the way in which this decision is made and the consequences surrounding it. It seems reasonable to standardise individualised records for this purpose.

Evaluar cómo han variado las decisiones de limitación del tratamiento de soporte vital (LTSV) en una unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) de tercer nivel a lo largo de un período de diez años.

MétodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo y comparativo, en la UCI de un hospital universitario terciario en España, desde enero de 2005 hasta diciembre de 2014. Mediante el análisis de la base de datos informatizada del servicio, se obtuvo la muestra de enfermos en los que se realizó LTSV en el periodo descrito. Se presentan las variables categóricas como frecuencias absolutas y porcentajes, y las cuantitativas como media y desviación estándar. La χ2 se utilizó para evaluar la significación estadística de las variables categóricas y se utilizó la t de Student en las variables cuantitativas. La relación entre las variables y la decisión de LTSV se estudió mediante regresión logística.

ResultadosLTSV se realizó en 409 (4,95%) a partir de 8.258 pacientes estudiados. El análisis comparativo mostró diferencias significativas entre el valor de APACHE II el día de la decisión LTSV (p=0,0001), se produjo una modificación en la distribución del tipo de LTSV, el estado de salud de los pacientes previa al ingreso en la UCI y mortalidad en la UCI en diferentes etapas. La LTSV tipo I pasó de ser el tipo de LTSV más frecuente en el año 2005, a ser el menos una década después (26,06%; IC95%: 15,60-40,26 frente a 7,32%; IC95%: 2,52-19,43). Actualmente la LTSV tipo V se ha convertido en frecuencia en la segunda opción (19,51%; IC95%: 10,23-34,01) cuando se decide la LTSV.

ConclusiónLas decisiones de LTSV han cambiado la forma y las consecuencias de tomar esta decisión. Parece razonable estandarizar registros individualizados para tal finalidad.

The advancement of medicine in recent decades has, on the one hand, made it possible for patients to live longer and, on the other hand, for physicians in intensive care units (ICUs) to develop the ability to prolong life, even in situations in which death seems inevitable.1

When the initial aim of treatment is not possible, the initial therapeutic approach changes, giving rise to the limitation of life-sustaining treatment (LLST) and end-of-life care.2

The General Law on Health opens the way for a further regulation in Law 41/2002 of 14 November, basic regulation of patient autonomy and of rights and obligations in the field of information and clinical documentation, which completes the provisions that the General Law on Health stated as general principles. In this sense, it reinforces and gives special treatment to the right to patient autonomy, with special emphasis on the patient's prior consent. This must be obtained after receiving adequate information, and must be in writing in the cases provided for in the Law; the right of the patient to decide freely between the available clinical options after receiving adequate information and the right to refuse treatment, except in the cases determined in the Law. Denial of treatment must be made in writing.3

It seems reasonable to think that this new legal regulation would have driven, at the time, a new doctor–patient relationship based on autonomy over the previous paternalistic model and in turn that this fact would reflect substantial changes in the decisions regarding LLST.4,5

Moreover, in the following years, different medical societies emphasised the specific recommendations for end-of-life care in our country's ICUs.6,7

However, the impact of this new scientific-legal configuration on end-of-life decisions within Spanish ICUs has been evaluated in a secondary way.8,9

The main objective of this study is to learn the factors associated with LLST decision-making in a third-level ICU over a period of ten years.

Subjects and methodsStudy design and scopeThis is an observational, retrospective and comparative study of patients admitted to the ICU in a single tertiary care centre in Spain between January 2005 and December 2014.

Population and sampleThe inclusion criteria in the study were being older than 18 years at the time of admission and having been admitted to the ICU during the study period (2005–2014). The exclusion criteria were being younger than 18 years, having been admitted to the ICU to receive a minor procedure with admission of less than 24h and/or having entered the ICU to receive terminal sedation during the study period.

Variables and data collectionThe intensive medicine department has a computerised database that is completed through a form. Each doctor responsible for the patient completes this when the patients are discharged from the ICU.

This form consists of a first section of identification, a second section with the characteristics of the patient on admission, a third of the characteristics of the patient at discharge, a fourth with the procedures applied in the ICU, a fifth documenting the infections on admission to the ICU and a sixth with the severity scores of the patient. Finally, the main and secondary diagnoses of the patients are recorded, choosing from 271 predefined diagnoses and grouped into 11 categories: cardiovascular, nervous system, haematology, respiratory, endocrine, infectious, gynaecological/obstetrical, gastrointestinal, renal, traumatological and others.

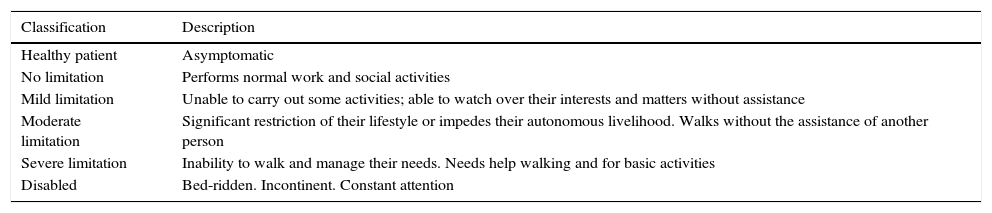

The variables that were collected from the database of the unit in addition to the LLST were: demographic (age and sex); clinical variables (date of admission, date of discharge or death, category of the main diagnosis of the patients which led to admission to the ICU [cardiovascular, digestive, haematological, endocrine, renal, respiratory, systemic, central nervous or neuromuscular system, traumatic, clinical monitoring or other]); previous performance status of the patient based on the modified Rankin scale10,11 (Table 1); severity on admission to the ICU (assessed by the APACHE II scale).12

Modified Rankin scale.

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Healthy patient | Asymptomatic |

| No limitation | Performs normal work and social activities |

| Mild limitation | Unable to carry out some activities; able to watch over their interests and matters without assistance |

| Moderate limitation | Significant restriction of their lifestyle or impedes their autonomous livelihood. Walks without the assistance of another person |

| Severe limitation | Inability to walk and manage their needs. Needs help walking and for basic activities |

| Disabled | Bed-ridden. Incontinent. Constant attention |

Modified from Rankin.10

From the review of the medical records, the following information was obtained: type of LLST performed according to the modified Gómez-Rubí classification,13 APACHE II the day when the LLST decision was taken, the time elapsed between the LLST decision and time of death, if this occurred, and the status of patients at discharge by the intra-ICU mortality dichotomous variable: yes or no.

Data analysisThe patients were classified into two groups: on the one hand, those in which LLST was performed and the other in which LLST was not performed.

The patients on whom LLST was performed were classified according to the date of admission to the ICU in two groups: those who were admitted to the ICU during the study period between January 2005 and December 2009 (first five years) and those who were admitted between January 2010 and December 2014 (second five years).

A descriptive analysis of the sample was performed initially. The results were presented as absolute frequency and percentage of the sample (with 95% confidence interval [95% CI], calculated by the Wald method) for the categorical variables; and as mean plus standard deviation for the continuous quantitative variables.

The comparative analysis was performed using the Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2) (with Yates correction in the applicable cases) or the Fisher exact test for the comparison of categorical proportions. The comparison of the quantitative variables with respect to the categorical variables was performed using the Student's t-test, except when it was not possible to assume homogeneity of the samples by using the Levene test, in which case the Welch test was used.

The data were processed with the IBM® SPSS® Statistics® 22.0 software programme.

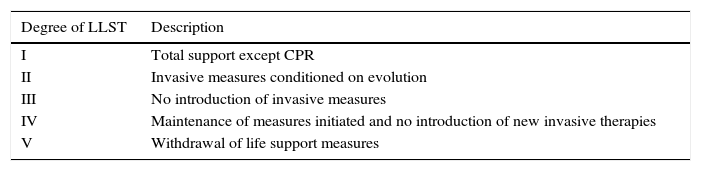

Ethical considerationsOur intensive medicine department has a Protocol of Limitation and Adaptation of Therapeutic Effort in paper and electronic format, available to all members of the medical and nursing staff; it was updated in 2013. This protocol establishes a series of guidance criteria in relation to the limitation of ICU patient admissions, the decision not to initiate new therapies and to withdraw them. The therapeutic efforts are individualised adopting the classification proposed by Gómez-Rubí in his book “Ethics in Critical Medicine”13 (Table 2).

Modified Gómez-Rubí scale for LLST.

| Degree of LLST | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Total support except CPR |

| II | Invasive measures conditioned on evolution |

| III | No introduction of invasive measures |

| IV | Maintenance of measures initiated and no introduction of new invasive therapies |

| V | Withdrawal of life support measures |

Modified from Gómez-Rubí.13

The review was carried out by three members of the research team who were not involved in the subsequent data analysis, either in paper or electronic format.

All data were processed in accordance with the organic law of personal data protection. The study was approved by the Hospital's Ethics Committee. The lack of intervention justified the withdrawal of the need for informed consent.

ResultsDuring the study period, a total of 8258 patients were collected through the registration form at discharge in the computerised database of the Intensive Medicine Department. The mean age of the total of 8258 patients was 59.47 (17.97) years, with 63% (95% CI: 59.81–66.38) male. The mean value of the APACHE II scale at admission was 18.17 (8.51), the mean length of stay was 11.52 (90.78) days and mortality in the ICU was 23% (95% CI: 21.21–27.03).

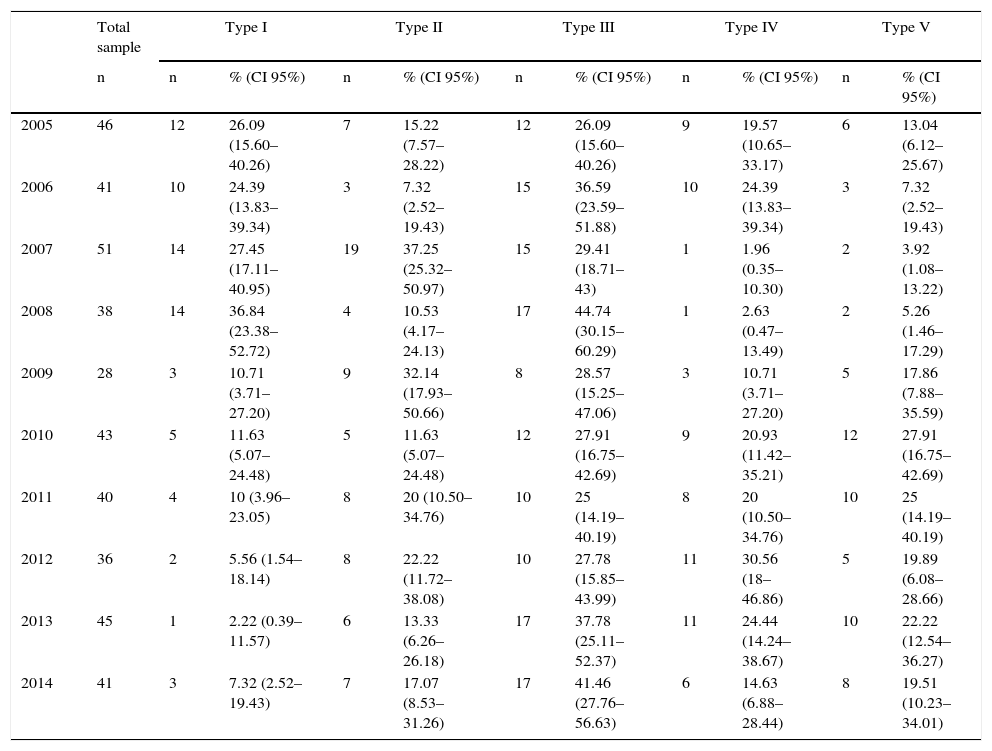

LLST was performed on 409 (4.95%) patients of the 8258 patients studied. The annual distribution of the types of LLST performed is reflected in Table 3.

Distribution of the different types of LLST, as per the modified Gómez-Rubí scale, throughout the 10 years of the study.

| Total sample | Type I | Type II | Type III | Type IV | Type V | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % (CI 95%) | n | % (CI 95%) | n | % (CI 95%) | n | % (CI 95%) | n | % (CI 95%) | |

| 2005 | 46 | 12 | 26.09 (15.60–40.26) | 7 | 15.22 (7.57–28.22) | 12 | 26.09 (15.60–40.26) | 9 | 19.57 (10.65–33.17) | 6 | 13.04 (6.12–25.67) |

| 2006 | 41 | 10 | 24.39 (13.83–39.34) | 3 | 7.32 (2.52–19.43) | 15 | 36.59 (23.59–51.88) | 10 | 24.39 (13.83–39.34) | 3 | 7.32 (2.52–19.43) |

| 2007 | 51 | 14 | 27.45 (17.11–40.95) | 19 | 37.25 (25.32–50.97) | 15 | 29.41 (18.71–43) | 1 | 1.96 (0.35–10.30) | 2 | 3.92 (1.08–13.22) |

| 2008 | 38 | 14 | 36.84 (23.38–52.72) | 4 | 10.53 (4.17–24.13) | 17 | 44.74 (30.15–60.29) | 1 | 2.63 (0.47–13.49) | 2 | 5.26 (1.46–17.29) |

| 2009 | 28 | 3 | 10.71 (3.71–27.20) | 9 | 32.14 (17.93–50.66) | 8 | 28.57 (15.25–47.06) | 3 | 10.71 (3.71–27.20) | 5 | 17.86 (7.88–35.59) |

| 2010 | 43 | 5 | 11.63 (5.07–24.48) | 5 | 11.63 (5.07–24.48) | 12 | 27.91 (16.75–42.69) | 9 | 20.93 (11.42–35.21) | 12 | 27.91 (16.75–42.69) |

| 2011 | 40 | 4 | 10 (3.96–23.05) | 8 | 20 (10.50–34.76) | 10 | 25 (14.19–40.19) | 8 | 20 (10.50–34.76) | 10 | 25 (14.19–40.19) |

| 2012 | 36 | 2 | 5.56 (1.54–18.14) | 8 | 22.22 (11.72–38.08) | 10 | 27.78 (15.85–43.99) | 11 | 30.56 (18–46.86) | 5 | 19.89 (6.08–28.66) |

| 2013 | 45 | 1 | 2.22 (0.39–11.57) | 6 | 13.33 (6.26–26.18) | 17 | 37.78 (25.11–52.37) | 11 | 24.44 (14.24–38.67) | 10 | 22.22 (12.54–36.27) |

| 2014 | 41 | 3 | 7.32 (2.52–19.43) | 7 | 17.07 (8.53–31.26) | 17 | 41.46 (27.76–56.63) | 6 | 14.63 (6.88–28.44) | 8 | 19.51 (10.23–34.01) |

Modified from Gómez-Rubí.13

In the patients admitted to the ICU with CNS or neuromuscular dysfunction, a higher percentage of LLST was performed (8.41%), followed by patients with respiratory dysfunction (5.77%) and digestive dysfunction (5.47%). In cases where LLST was decided, when the patient died (76.52%), this occurred on 40% of the occasions in the first 12h from the moment the decision was taken.

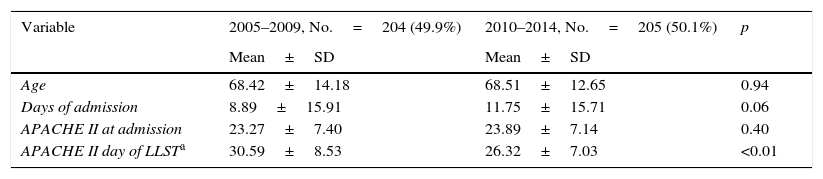

The comparative analysis between the two five-year periods selected showed that during the period of 2005–2009, the overall mean age of the sample was 58.41±18.21 years versus 59.58±17.88 of the second period analysed (p=0.004). There were no significant differences in the days of ICU stay between patients in the two periods. There were significant differences between the APACHE II value when deciding LLST (30.59±8.53 in the first five-year period and 26.32±7.03 in the second five-year period; p=0.0001), the percentage of patients who died within the first 12h from the time LLST was decided (25.9% versus 47.8%), the patients’ previous health status at ICU admission, type of LLST and intra-ICU mortality at the different stages (72.05% versus 80.97%) (Table 4).

Comparative of the clinical-demographic variables in patients with LLST between two five-year periods.

| Variable | 2005–2009, No.=204 (49.9%) | 2010–2014, No.=205 (50.1%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| Age | 68.42±14.18 | 68.51±12.65 | 0.94 |

| Days of admission | 8.89±15.91 | 11.75±15.71 | 0.06 |

| APACHE II at admission | 23.27±7.40 | 23.89±7.14 | 0.40 |

| APACHE II day of LLSTa | 30.59±8.53 | 26.32±7.03 | <0.01 |

| n (% [95% CI]) | n % ([95% CI]) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 120 (58.8% [51.97–65.35]) | 139 (67.8% [61.13–73.82]) | 0.05 |

| Death | |||

| First 12h after LLST | 53 (25.9% [20.43–32.42]) | 98 (47.8% [41.07–54.62]) | <0.01 |

| Diagnosis at admissionb | |||

| Clinical surveillance | 3 (1.5% [0.51–4.30]) | 0 (0% [0–1.87]) | 0.12 |

| Traumatic | 9 (4.4% [2.37–8.29]) | 3 (1.5% [0.51–4.27]) | 0.07 |

| CNS/neuromuscular | 55 (26.9% [21.67–33.91]) | 59 (28.8% [23.37–35.82]) | 0.68 |

| Systemic | 32 (15.7% [11.51–21.61]) | 19 (9.3% [.10–14.22]) | 0.04 |

| Respiratory | 42 (20.6% [15.85–27.04]) | 67 (32.7% [27.04–39.92]) | <0.01 |

| Renal | 0 (0% [0–1.88]) | 1 (0.5% [0.09–2.75]) | – |

| Metabolic | 1 (0.5% [0.09–2.76]) | 2 (1% [0.27–3.54]) | >0.99 |

| Haematological | 7 (3.4% [1.70–7.01]) | 1 (0.5% [0.09–2.75]) | 0.03 |

| Gastrointestinal | 38 (18.6% [14.09–24.68]) | 22 (10.7% [7.30–15.94]) | 0.02 |

| Cardiovascular | 12 (5.9% [3.45–10.14]) | 25 (12.2% [8.53–17.63]) | 0.02 |

| Previous conditionc | |||

| Healthy | 30 (14.93% [10.66–20.51]) | 21 (10.71% [7.12–15.82]) | 0.82 |

| Disease without limitation | 31 (15.42% [11.08–21.06]) | 25 (12.76% [8.79–18.15]) | 0.56 |

| Mild limitation | 28 (13.93% [9.82–19.40]) | 23 (11.73% [7.95–16.99]) | 0.75 |

| Moderate limitation | 31 (15.42% [11.08–21.06]) | 56 (28.57% [22.71–35.26]) | <0.01 |

| Severe limitation | 55 (27.36% [21.67–33.91]) | 62 (31.63% [25.53–38.44]) | 0.03 |

| Disabled | 26 (12.94% [8.98–18.28]) | 9 (4.59% [2.43–8.50]) | <0.01 |

| Type of LLST | |||

| I | 53 (25.98% [20.45–32.40]) | 15 (7.32% [4.48–11.72]) | <0.01 |

| II | 42 (20.59% [15.61–26.66]) | 34 (16.59% [12.12–22.28]) | 0.29 |

| III | 67 (32.84% [26.77–39.55]) | 66 (32.20% [26.18–38.87]) | 0.88 |

| IV | 24 (11.76% [8.03–16.91]) | 45 (21.95% [16.83–28.10]) | <0.01 |

| V | 18 (8.82% [5.65–13.52]) | 45 (21.95% [16.83–28.10]) | <0.01 |

| Mortality | 147 (72.05% [65.54–77.76]) | 166 (80.97% [75.05–85.76]) | 0.03 |

This study compares the form and consequences in the decision making at the end of life in a Spanish ICU of a third level hospital over two five-year periods. The main limitation of this study is its retrospective character, where there is a bias of memory and/or registration, magnified perhaps by the lack of a registration of the decisions of the adequacy or limitation of the end-of-life treatments. In fact, sometimes the patient's medical history did not detail the decision taken. The information described was not homogeneous and had to be completed with the treatment sheet or with the constant collection graph.

However, LLST decisions have become a standard practice in our ICU, which is in line with a study of similar characteristics conducted in a Spanish ICU (Madrid) during the period 2002–2009, with 5.7% of ALST in the analysed cohort.14 Their frequency (4.9%) did not change over a decade in our ICU; however, the form and consequences of making this decision varied. This situation is reflected in the variation of the APACHE II score at the time of the decision taken between the two five-year periods studied, the percentage of patients who died in the first hours after the LLST was decided, the intra-ICU mortality of the patients analysed and, above all, the variation in the type of LLST in the two five-year periods studied.

This variation could be explained by differences in the preferences of patients and relatives at the end of life by virtue of the prognosis, religious beliefs, ethical and/or legal issues; the type of intensive care unit and the differences in approach, description and classification of the LLST decisions themselves,15–20 which, in addition can be modified in time in the same scenario by virtue of contextual legal, religious, etc., modifications. In the same way we consider it extremely important to differentiate these facts from the refusal or rejection of certain treatments.

One good example can be found in a recent French study,21 conducted in 2013 with the intention of gauging the impact of the Leonetti Law on the rights of patients and end of life in France. This provision pursued the objective of strengthening the rights of the patient and granting specific rights to the terminally ill.22 After performing a prospective collection in 43 intensive care units in France over a period of 60 or 90 days in the first half of 2013, it was shown that up to 52% of the deceased patients had taken a decision on LLST. This frequency increased significantly to 70% in patients with brain lesions.23 This figure is in line with our findings, which give these patients a higher frequency of LLST. These data unequivocally contrast with the data presented by the French group LATAREA24 in relation to LLST decisions that were made in 1997 in a total of 113 French ICUs. In this study, the frequency of LLST was 11%. These two French studies, which were completed 16 years apart, after the promulgation of the Leonetti Law, are the basis of the argument that the law provides a legal framework for practices that already existed informally in ICUs in that country.

The intra-ICU mortality of patients with LLST in our study stands at an average of 76% over 10 years, a figure that is within reasonable margins when compared to the mortality (60–98%) evidenced in other series.4,13,16,20,23 However, a higher value was obtained in the second five-year period studied with respect to the first one (72.05 compared to 80.97%; p=0.036). It seems reasonable to consider this information suitable considering different premises such as: the modification in the type of LLST produced, LLST in patients with lower APACHE II; and in patients who, prior to admission to the ICU, had a higher percentage of limitations considered moderate or severe in their daily life. This decision was associated with the fact that the time elapsed since the decision was taken and death was significantly lower.

In conclusion, from the data analysed, a change in the way decisions are currently taken at the end of life seems to be evidenced. However, it seems logical to think that there are still steps to take in the future. Special mention could be made of the individualised records of end-of-life treatments. In this sense, the most internationally known document is the one developed in the United States under the name of POLST.25 POLST is a registration form of clinical orders, both for medicine and for nursing, which establishes what should and should not be done in cases of LLST in an individualised way. The establishment of this series of records could result in better communication between all the parties that are part of this process.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González-Castro A, Rodríguez Borregán JC, Azcune Echeverria O, Perez Martín I, Arbalan Carpintero M, Escudero Acha P, et al. Evolución en las decisiones de limitación de los tratamientos de soporte vital en una unidad de cuidados intensivos durante una década (2005-2014). Rev Esp Med Legal. 2017;43:92–98.