In this paper, a study is made of the effects of local and cross-border cooperation between small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) on company innovation and performance. In line with previous works, it is maintained that cooperation positively impacts on company performance and innovation levels, while also finding that this effect is likely to be moderated by just how the firm conceives its cooperation configuration.

A bivariate linear model was used to test a a sample of 61 Portuguese and Spanish cross-border SMEs. The results confirm that cooperation is positively associated with company performance and innovation results. However, the cooperation configuration reveals different characteristics. It is conclude that co-operation with suppliers and qualified human resources are determining factors of local co-operation. In contrast, innovation related activities are crucial to cross-border cooperative activities. Overall, a contribution is made to the existing local and cross-border co-operation literature by demonstrating how SMEs may leverage increasing returns when able to combine innovation and cooperation.

En este trabajo, se estudian los efectos de la cooperación local y transfronteriza entre las pequeñas y medianas empresas (PYME) sobre la innovación y el desempeño de la empresa. En línea con anteriores trabajos, mantenemos que la cooperación tiene un impacto positivo sobre el desempeño de la empresa y los niveles de innovación al mismo tiempo se constata que este efecto es probable que sea moderado por el modo cómo la empresa concibe su configuración de cooperación. Tomando una muestra de 61 PYME transfronterizas de Portugal y España, analizamos empíricamente un modelo lineal de dos variables. Nuestros resultados confirman que la cooperación se asocia positivamente con los resultados de desempeño de la empresa y de innovación. Sin embargo, la configuración de la cooperación muestra características diferentes. Llegamos a la conclusión de que la cooperación con los proveedores y recursos humanos calificados son determinantes para la cooperación local. Por el contrario, las actividades relacionadas con la innovación son fundamentales para las actividades de cooperación transfronteriza. En general, contribuimos a la literatura de cooperación local y transfronteriza existente al demostrar cómo las PYME pueden aprovechar los rendimientos crecientes, cuando sean capaz de combinar la innovación y la cooperación.

Since the mid-1990s, cooperation based activities have extended beyond the realm of multinationals and other major corporations with small and medium sized companies increasingly engaging in this management practice (Bönte & Keilbach, 2005; Hagedoorn, Albert, & Vonortas, 2000; Laursen & Salter, 2006; Rosenfeld, 1996). The very image of independent economic actors striving to make profits in open competition in impersonal markets is proving increasingly inadequate in a time when companies are establishing ever more means of mutual cooperation (Gulati, 1998; Gulati, Nohria, & Zaheer, 2000). Ever deeper and more complex knowledge processes, within the framework of which new technologies and innovation form the very backbone, drive companies into reaching beyond existing knowledge and qualifications and leading them to strive to complement their own capacities (Becker & Dietz, 2004; Nijssen, Van Reekum, & Hulshoff, 2001). Within this context, cooperation plays an increasingly important role in innovation related activities (Ahuja, 2000; Cassiman & Veugelers, 2002; Hagedoorn, 2002; López, 2008). As from the point when cooperation for innovation proves able to empower the accumulation of knowledge susceptible to conversion into new technological and organisational innovations, those companies engaging in such cooperation effectively open up their range of technological options (Caloghirou, Ioannides, & Vonortas, 2003; Mowery, Oxley, & Silverman, 1998). Hence, companies actively involved and participating in cooperation based activities are inherently exposed to denser flows of knowledge than non-cooperating entities (Gomes-Casseres, Hagedoorn, & Jaffe, 2006).

Cooperation activities with other companies and institutions thus represent opportunities to access the resources and technological knowledge that nurture and foster rapid developments in innovations, access to new markets, economies of scale and the sharing of both risks and costs (Ahuja, 2000; Cassiman & Veugelers, 2002; Hagedoorn, 2002; López, 2008). Another factor ensuring companies turn to cooperation is the balance between the high rates of knowledge generated while also simultaneously protecting and defending the internal knowledge already existing at the company (Schmidt, 2005).

Cooperation between companies located in border regions has drawn the attention of various researchers (Braczyk, Cooke, & Heidenreich, 1998; Roper, 2007). Border regions are characterised precisely by the conditions prevailing and contrasting with those in effect elsewhere: economic discontinuities and low levels of human capital (Mitko, George, Stoyan, & Maria, 2003; Petrakos & Tsiapa, 2001). In this context, cross-border cooperation might play a fundamental role in overcoming the discontinuities these regions commonly face while simultaneously generating dynamic and positive regional growth (Pablo, 2012; Roper, 2007; Teague & Henderson, 2006).

The main findings of the most recent contributions within this framework point to differing determining factors and dependent on the type of cooperation and partnership (Belderbos, Carree, & Lokshin, 2004; Fritsch & Lukas, 2001; Mention, 2011; Tether, 2002). Fritsch and Lukas (2001) conclude how innovation related efforts designed to improve processes are most likely to involve cooperation with suppliers while product related innovations are associated with cooperating with clients. Tether (2002) concludes that cooperation is mostly the domain of companies aiming for more radical innovations than incremental innovations. In differentiating between partnerships involving competitors, suppliers, clients, universities and research institutes, Belderbos et al. (2004) point out substantial heterogeneity in the determinants establishing the different partnerships. Mention (2011) identifies the influence held by cooperation based practices on the propensity of companies to introduce new innovations into the market. The key issue as to whether or not such cooperation based actions actually generated the positive expected impact on innovation and performance has remained practically ignored by the respective literature (Das & Teng, 2000; Tether, 2002). A series of research studies have incorporated a cooperation variable into empirical models designed to explain differences in company innovation results (Klomp & Van Leeuwen, 2001; Lööf & Heshmati, 2002; Monjon & Waelbroeck, 2003). However, the majority of these studies primarily focused on the impact of research and development (R&D) investment on performance and failed to systematically examine the differences in impacts across the various types of cooperation. Management studies have hitherto limited their analysis to performance indicators specific to particular industries, for example, the effects of alliances on the performance of high technology start-ups in the biotechnology sector (Baum, Calabrese, & Silverman, 2000) or the effect of alliance based learning on performance in terms of market share in the global automobile industry (Dussauge, Garrette, & Mitchell, 2002).

The present study seeks to determine just which business characteristics and regional perceptions influence the probability of cooperation between local or cross-border companies in two specific regions of two countries: the Centro (in Portugal) and the Castilla and Leon (in Spain) regions as well as measuring their respective influence on innovation and performance.

This article is structured as follows: firstly, we undertake a review of the literature on space, cooperation and innovation and thereby formulating our research hypotheses. In the second section, we set out our methodology, the data and the research sample. Thirdly, we present the empirical results obtained before concluding with some final considerations.

Literature reviewSpace, cooperation and innovationVarious schools dedicated to the study of regional economic theory have emphasised how explaining regional development inherently involves the economic, social, institutional and cultural characteristics that jointly establish the prevailing development capacities (Maskell, Eskelinen, Hannibalsson, Malmberg, & Vatne, 1998), interdependent transactions (Storper, 1997), or even the implementing of regional development infrastructures able to facilitate mutual learning between regional actors (Florida, 2010; Morgan, 1997). Common to all these authors is the importance attributed to learning and innovation to economic development and hence they correspondingly perceive relational exchanges between regional actors as a pathway towards attaining that same development (Rutten, 2003).

According to Scott (1998), the surrounding space shapes transactions in three different ways: (i) small scale transactions are generally only economic when carried out over short distances as they lack the economies of scale dimension; (ii) irregular transactions are more difficult to sustain over longer distances than standardised and predictable transactions; (iii) different modes of transaction (for example, face-to-face meetings in contrast with electronic transactions) generate different implications for spatial costs.

Porter's (1998) contribution held a very significant influence in the debates surrounding regional development and innovation. Combined actions between marketplaces, suppliers, the terms and conditions of factors of producer competitiveness are the building blocks for innovation, productivity and strengthened competitiveness. Porter's diamond (which provides a graphical representation of the combined actions described above) may be seen as a portrait of the social space required for changing knowledge, cooperation and innovation. Porter (1998) defends how local clusters would become more common as competitive advantage is intrinsically bound up with local characteristics, such as knowledge, relationships and motivation and thereby rendering innovation continuous. Through empirical studies, Porter (2003) demonstrates the way in which the regional economies of the United States are strongly influenced by the power of their local clusters of innovation. The role of government in local development is verified through the cooperation ongoing between the clusters and public education systems and infrastructures.

The Italian industrial districts, in particular Emilia Romagna, achieved a very high profile between 1980 and 1990, and the work undertaken in these environments has decisively influenced various researches on the role of location in innovation (Cossentino, Pyke, & Sengenberger, 1996; Pyke, Becattini, & Sengenberger, 1992). The combination of flexible specialisation between small and medium sized companies and their respective system of organisation would seem to foster overall competitiveness (Lorentzen, 2008). Becattini and Rullani (1996), in turn, propose that the local context is essential to competitiveness through two core mechanisms: (i) the local context may be considered an input into the production process to the extent that the work of entrepreneurs, tangible and intangible infrastructures, the institutional cultural and social models are contributions rendering local production unique. Hence, the local system of production is both autonomous and highly important to private sector competitiveness. (ii) The local system performs a fundamental role in converting the knowledge necessary to successful company operations. The new knowledge, generated beyond any local contexts, is spread and acquired through inter-company cooperation and subsequently contextualised by participating companies. The new location of knowledge, nurtured within the extent of local systems, fosters the latter's means of codifying the global system and thereby generating innovation.

Various empirical researches have confirmed how face-to-face contacts and geographic proximity are important factors in the diffusion of innovation and in certain specific knowledge exchanges (Gomes-Casseres et al., 2006; Morgan, 2004) and drive better access to information (Porter, 1990). In his study, Bell (2005) concludes that companies should ideally locate in an industrial cluster and in a central position in whatever network is responsible for the greatest increases in innovation. As regards biotechnology sector companies, Aharonson, Baum, and Feldman (2004) consider that whenever such companies are grouped into clusters, they generate more innovation than when geographically dispersed.

Sonn and Storper (2003) also reaffirm the positive effect of geographic proximity on innovation. A different study by Almeida and Kogut (1997) finds that regions differ between each other in terms of how they localise knowledge and the mobility of the patents generated locally. Researchers also defend that small companies exploring new technological domains prove more successful when operating in locations where the network density is greater (Almeida & Kogut, 1997). Audretsch and Lehmann (2006) report how locating within the vicinity of universities proves to be a highly important factor to the performance levels of German companies.

Despite the otherwise generalised opinion that geographic proximity leads to higher performance standards in terms of innovation, there is one current in the literature that questions this theory. For example, Boschma (2005) stresses the role played by the proximity between institutions and companies while another study, by Boschma and Ter Wal (2007), shows that this is not only about the local connections in effect but also that interconnections with the global market also serve to boost company innovation performance levels. The conclusions reached by Rallet and Torre (1999) also point in the same direction whilst based upon case studies on three French regions. Other studies show how social connections might be of greater importance than mere geographic proximity (Agrawal, Cockburn, & Mchale, 2006; Balconi, Breschi, & Lissoni, 2004; Sorenson, 2003). The growing emphasis on social connections implies that the existence of networks and social relationships is of genuine relevance and hence geographic proximity is not the only influence on innovation related questions. Other studies consider global connections as a complement to local bonds and relationships in terms of company performance. Doloreux (2004) returns similar results in a case study of Canadian small and medium sized companies (SMEs) with connections with both clients and suppliers beyond the region. This result is also confirmed by Oerlemans, Marius, Meeus, and Boekema (2001) when studying the case of the Netherlands and finding that strong external links bear a strong impact on the innovation performances in effect at companies. Therefore:H1a Local cooperation positively impacts on the firm's performance. Cross-border cooperation positively impacts on the firm's performance.

Given the consensus surrounding innovation as a complex process, SMEs necessarily confront obstacles to innovation and only manage to innovate through cooperating with other companies optimising their utilisation of their own internal knowledge and combining it with the specific competences their respective partners bring to the table (Muller & Zenker, 2001). Kleinknecht (1989) identifies the following obstacles to innovation: (i) the shortage of financial capital; (ii) a shortfall in the availability of suitable management staff; (iii) difficulties in obtaining the technological information and know-how necessary to innovation. In turn, Bughin and Jacques (1994) affirm that the major obstacle to innovation does not so much derive from company “myopia”, but fundamentally due to their incapacity to adopt what they themselves designate as their “core management principles”: (i) efficiency in marketing and in R&D; (ii) leveraging synergies between marketing and R&D; (iii) communication capacities; (iv) organisational excellence and innovation management; (v) innovation protection. This would correspondingly suggest that, for the majority of companies, internal R&D proves insufficient for the acquisition of knowledge able to drive innovation.

Very commonly and in particular at small innovative firms, idiosyncratic internal capacities, closely related to the owner's entrepreneurial profile, or his/her respective experiences, motivations, networks, creativity, strategic orientation as well as the respective innovation activities ongoing (Ferreira, 2010; Lynskey, 2004; Webster, 2004).

However, the actual measuring of innovation is problematic and particularly in terms of services as there is no prevailing consensus on its conceptualisation (Flikkema, Jansen, & Van Der Sluis, 2007). According to the Oslo Manual (OECD, 1997), non-technological innovation covers all forms of innovation and hence those not only related with the introduction of new technologies or significant changes in goods and service but also in the adoption of new processes. Innovation may be approached from different perspectives that differ in terms of the respective objects focused upon, in the concepts, strategic conceptions, the methodologies and models, and in their measuring and their analysis (Souitaris, 2002). Recently, researchers have especially emphasised the role of company characteristics and the actual factors that lead them to innovating (Hwang, 2004; Lemon & Sahota, 2004; Tidd & Bessant, 2009). Some studies maintain that the appearance of new ideas, fundamental to company innovation capacities, inherently depends on the creation of new knowledge (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Koc & Ceylan, 2007; Macdonald & Williams, 1994).

In accordance with the importance of creating new ideas, there is correspondingly new relevance attributed to their correct transmission and utilisation inside companies alongside how such ideas might be shared and applied to leverage innovation (Monge, Cozzens, & Contractor, 1992; Tidd & Bessant, 2009). The internal company environment in terms of its structure and organisational development, the appropriateness of the innovation strategy and its communication to members of staff thereby emerge as factors fundamental to innovation (Lemon & Sahota, 2004; Roberts & Berry, 1985; Slappendel, 1996; Wheelwright & Clark, 1995). Questions thus include how to encourage employees to participate in innovation processes in innovation propitious ways (Slappendel, 1996; Wheelwright & Clark, 1995). Organisational cultures able to foster creativity and spread and advance knowledge among the various members of staff with different capacities and roles certainly enable companies to solve problems through generating synergy effects (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996; Damanpour & Gopalakrishnan, 1998; Lemon & Sahota, 2004; Mcgourty, Tarshis, & Dominick, 1996). Nevertheless, and as Dussage, Hart, and Ramanantsoa (1992) defends, the choice of an appropriate organisational strategy or culture depends on the costs, deadlines and the risks the company is able to incur.

Innovation in processes may include innovations in products, fulfilling specific consumer needs as well as the acquisition of technology (Cooper, 1990; Koc & Ceylan, 2007; Roberts & Berry, 1985). More recently, a number of researchers have proposed the thesis that companies investing internally in R&D, making recourse to R&D outsourcing or participating in R&D networks are all able to drive innovative capacities (Castellani & Zanfei, 2004; Frenz & Ietto-Gillies, 2007; Moritra & Krishnamoorthy, 2004).H2a Local cooperation positively impacts on the firm's innovation. Cross-border cooperation positively impacts on the firm's innovation.

This research took place under the auspices of the ACTION project. The ACTION project is an international initiative for boosting cooperation in cross-border regions among firms in different industries in conjunction with the respective regional scientific and technological institutions to enhance the regional innovation profile. The geographical scope of the ACTION project is NUT II regions, which includes Castilla and Leon (Spain) and Centro (Portugal). This project involved 61 firms (26 Portuguese firms and 35 Spanish firms) belonging to the logistics and agro-food sectors with all firms agreeing to participate in the survey.

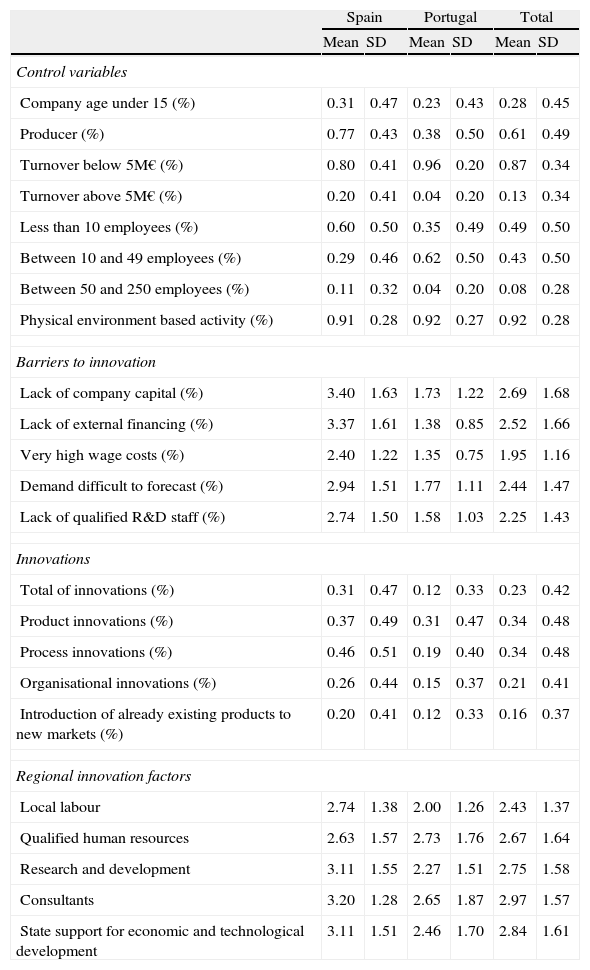

The descriptive results of the variables deployed in the analysis are set out in Table 1, with the variable definitions annexed. In terms of characterising the companies and understanding their context, we applied variables including length of service, scale and type of activity and, regarding the context, barriers to innovation, innovation capacity and the specific importance of some regional factors (Appendix).

Descriptive statistics.

| Spain | Portugal | Total | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Company age under 15 (%) | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

| Producer (%) | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.49 |

| Turnover below 5M€ (%) | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.96 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.34 |

| Turnover above 5M€ (%) | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| Less than 10 employees (%) | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Between 10 and 49 employees (%) | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Between 50 and 250 employees (%) | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| Physical environment based activity (%) | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.28 |

| Barriers to innovation | ||||||

| Lack of company capital (%) | 3.40 | 1.63 | 1.73 | 1.22 | 2.69 | 1.68 |

| Lack of external financing (%) | 3.37 | 1.61 | 1.38 | 0.85 | 2.52 | 1.66 |

| Very high wage costs (%) | 2.40 | 1.22 | 1.35 | 0.75 | 1.95 | 1.16 |

| Demand difficult to forecast (%) | 2.94 | 1.51 | 1.77 | 1.11 | 2.44 | 1.47 |

| Lack of qualified R&D staff (%) | 2.74 | 1.50 | 1.58 | 1.03 | 2.25 | 1.43 |

| Innovations | ||||||

| Total of innovations (%) | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.42 |

| Product innovations (%) | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.48 |

| Process innovations (%) | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.48 |

| Organisational innovations (%) | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| Introduction of already existing products to new markets (%) | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.37 |

| Regional innovation factors | ||||||

| Local labour | 2.74 | 1.38 | 2.00 | 1.26 | 2.43 | 1.37 |

| Qualified human resources | 2.63 | 1.57 | 2.73 | 1.76 | 2.67 | 1.64 |

| Research and development | 3.11 | 1.55 | 2.27 | 1.51 | 2.75 | 1.58 |

| Consultants | 3.20 | 1.28 | 2.65 | 1.87 | 2.97 | 1.57 |

| State support for economic and technological development | 3.11 | 1.51 | 2.46 | 1.70 | 2.84 | 1.61 |

Output STATA software.

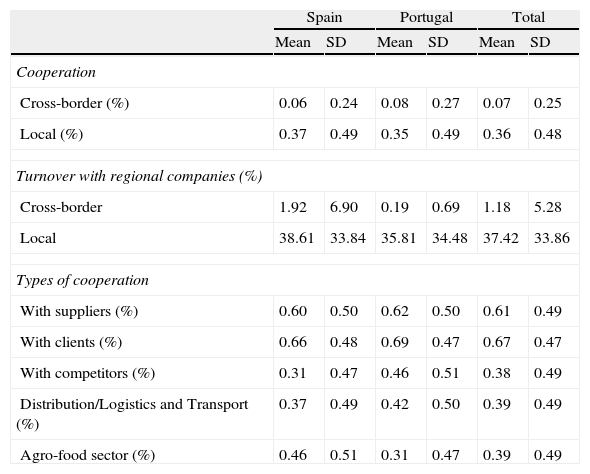

Table 2 presents the results relating to cooperation as a percentage of the turnover obtained regionally. In general terms, there is a high proportion of companies cooperating with 61% of companies reporting they cooperate with suppliers and 67% with clients. Local cooperation (36%) broadly prevails over cross-border cooperation (7%), both for Portuguese firms (Local: 35%; Cross-border: 8%) and for Spanish firms (Local: 37%; Cross-border: 6%). Correlating this result with the percentage of turnover between companies from the two countries returns only a very low level (1.18%) and especially in comparison with business transactions ongoing between regional firms within their own country (37.42%), although we should highlight that in both cases the percentages are higher in the case of Spanish companies (Local: 38.61%; Cross-border: 1.92%) than in Portuguese companies (Local: 35.81%; Cross-border: 0.19%).

Cooperation statistics.

| Spain | Portugal | Total | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Cooperation | ||||||

| Cross-border (%) | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| Local (%) | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.36 | 0.48 |

| Turnover with regional companies (%) | ||||||

| Cross-border | 1.92 | 6.90 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 1.18 | 5.28 |

| Local | 38.61 | 33.84 | 35.81 | 34.48 | 37.42 | 33.86 |

| Types of cooperation | ||||||

| With suppliers (%) | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.49 |

| With clients (%) | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.47 |

| With competitors (%) | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.49 |

| Distribution/Logistics and Transport (%) | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| Agro-food sector (%) | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

Output STATA software.

This study seeks to determine which business characteristics and regional perceptions influence the probability of cooperation taking place at local or cross-border firms in the Centro region of Portugal and the Castilla and Leon region of Spain, in addition to identifying the characteristics influencing regional business volumes.

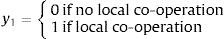

In relation to the probability of cooperation, given a possible relationship between local cooperation and cross-border cooperation as companies with greater propensities to cooperate experience this simultaneously across the local and the cross-border levels. We applied a Bivariate Probit Model to calculate the probability of the aforementioned cooperation types.

The model is defined as follows:

in which the terms of error ¿1and ¿2 display a normal distribution pattern with a zero average and unit variance and with ρ correlation. The variables y1 and y2 correspond to the variables defining the presence or absence of cooperation whereThe possible model results therefore assume the following values:p11=Pry1=1,y2=1=ϕ2xi'βˆ1i,x2i',ρˆ,p00=Pry1=0,y2=0=1−ϕxi'βˆ1i−ϕxi',βˆ2i−ϕ2(xi'βˆ1i,(xi'βˆ2i,ρˆ',p01=Pry1=0,y2=1=ϕxi'βˆ2i−ϕ2(xi'βˆ1i,xi'βˆ2i,ρˆp10=Pry1=1,y2=0=ϕxi'βˆ1i−ϕ2(xi'βˆ1i,xi'βˆ2i,ρˆ

in which ϕ2 corresponds to the accumulative function of the normal bivariate distribution with a ρ correlation between the two variables and ϕ is the accumulative function of the normal univariate distribution. The estimation of the bivariate model parameters was undertaken through the maximum likelihood methodology and we adopted robust error standard estimates to avoid erroneous inferences.

As regards determining the factors bearing statistically significant influence over the turnover generated by either local or cross-border company cooperation, we deployed a Bivariate Linear Model. The advantage of the joint estimation of the two equations derives from incorporating correlations between the equations thereby boosting the efficiency of the estimates returned.

The model under estimation with two dependent variables is

in which yi and ui are vectors 2×1, Xi is a matrix 2×K and β is column vector K×1. The equation estimation operation was then carried out by OLS.

The aforementioned model estimations were undertaken through recourse to STATA version 11 software.

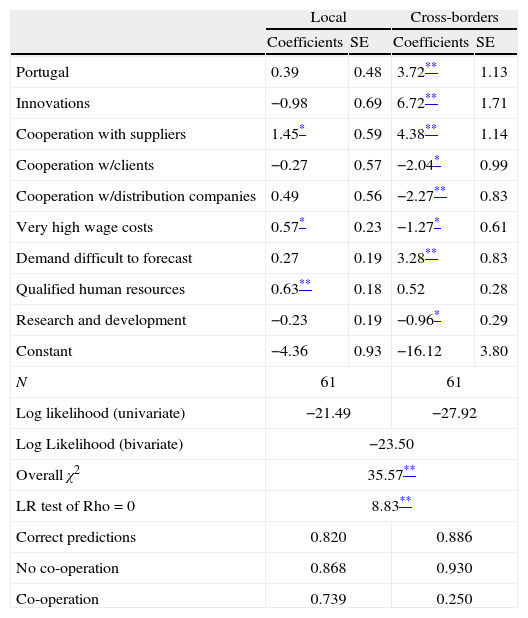

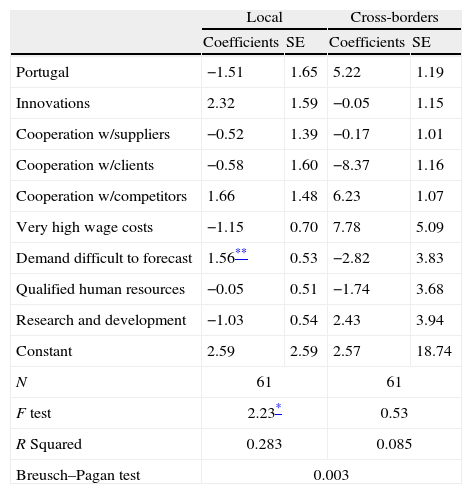

Empirical resultsWe estimated a bivariate probit model to ascertain the determinants of the probability of cooperation between local and cross-border companies of the Centro region of Portugal and the Castilla and Leon region of Spain (Table 3).

Bivariate probit model of cross-border and local co-operation.

| Local | Cross-borders | |||

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Portugal | 0.39 | 0.48 | 3.72** | 1.13 |

| Innovations | −0.98 | 0.69 | 6.72** | 1.71 |

| Cooperation with suppliers | 1.45* | 0.59 | 4.38** | 1.14 |

| Cooperation w/clients | −0.27 | 0.57 | −2.04* | 0.99 |

| Cooperation w/distribution companies | 0.49 | 0.56 | −2.27** | 0.83 |

| Very high wage costs | 0.57* | 0.23 | −1.27* | 0.61 |

| Demand difficult to forecast | 0.27 | 0.19 | 3.28** | 0.83 |

| Qualified human resources | 0.63** | 0.18 | 0.52 | 0.28 |

| Research and development | −0.23 | 0.19 | −0.96* | 0.29 |

| Constant | −4.36 | 0.93 | −16.12 | 3.80 |

| N | 61 | 61 | ||

| Log likelihood (univariate) | −21.49 | −27.92 | ||

| Log Likelihood (bivariate) | −23.50 | |||

| Overall χ2 | 35.57** | |||

| LR test of Rho=0 | 8.83** | |||

| Correct predictions | 0.820 | 0.886 | ||

| No co-operation | 0.868 | 0.930 | ||

| Co-operation | 0.739 | 0.250 | ||

SE – Robust Standard Error.

Output STATA software.

It did not prove possible to estimate an equal model for both countries due to the number of sample facts did not provide sufficient scope and reliability. The result of the Chi-Squared test [χ2(18)=35.57; p<.01] suggests that the model estimated is able to significantly forecast the cooperation variables. To carry out predictions, taking into consideration this predictive model capacity, we determined an “optimal” cut-off point through the point on the ROC curve closest to (0.1) method. Thus, for predicting which companies cooperate at the local level the cut-off point established was 0.52 and for cross-border cooperation the cut-off point was 0.12.

Based on these results, we find the cross-border cooperation model returns a high level of predictive capacity in terms of its overall performance (91.8% of companies correctly classified), for non-cooperating companies (91.2% of companies correctly classified) and an impressive predictive power for companies cooperating (exactly 100% correctly classified). In terms of the predictive power of the local cooperation model, there was also a good standard of performance for the sample as a whole (82% correctly classified), for cooperating companies (77.3% correctly classified) and non-cooperating firms (84.6% correctly classified).

Determinants of cooperationIn the case of local cooperation (Table 3), we find that the firms reporting the greatest propensity to develop local cooperation processes are companies cooperating with their suppliers (B=1.45; p<.05), that perceive wage costs as a barrier to innovation (B=0.57; p<.05) and consider the presence of qualified human resources important to innovation existing in regional terms (B=0.63; p<.01).

As regards cross-border cooperation, Portuguese companies display a greater propensity to develop such cross-border processes (B=3.72; p<.01). Companies that had engaged in innovative activities in the last year report a greater probability of cooperating at the cross-border level (B=6.72; p<.01), as well as companies cooperating with suppliers (B=4.38; p<.01) and that deem the forecasting of demand a barrier to innovation (B=3.28; p<.01). In terms of those companies with the least propensity to develop cross-border cooperation, the model identifies companies cooperating with clients (B=−2.04; p<.05) and with distribution companies (B=−2.27; p<.01), as well as those perceiving high wage costs prevailing regionally (B=−1.27; p<.05) and consider R&D a regional factor of relevance to company innovation capacity levels (B=−0.96; p<.05).

The Likelihood Ratios (LR) test for analysing the correlation [χ2(1)=8.83; p<.01] between the two models indicates that local and cross-border cooperation are significantly interrelated. Research hypotheses H2a and H2b are therefore statistically confirmed.

Hence, we find that local cooperation and cross-border cooperation, while displaying different characteristics (Petrakos & Tsiapa, 2001), both hold a positive impact on company innovation levels. Cooperation with suppliers, wage costs and qualified human resources are determinant factors for local cooperation. Firms engaging in cross-border cooperation attribute greater importance to innovative activities, cooperation with suppliers and the difficulties in forecasting demand. Of note is how Portuguese companies make greater recourse to this mode of cooperation than their Spanish counterparts. Furthermore, companies cooperating with clients do not opt for cross-border cooperation. Hence, the different modes of cooperation correspond to distinct differences in the companies responsible for them (Mitko et al., 2003).

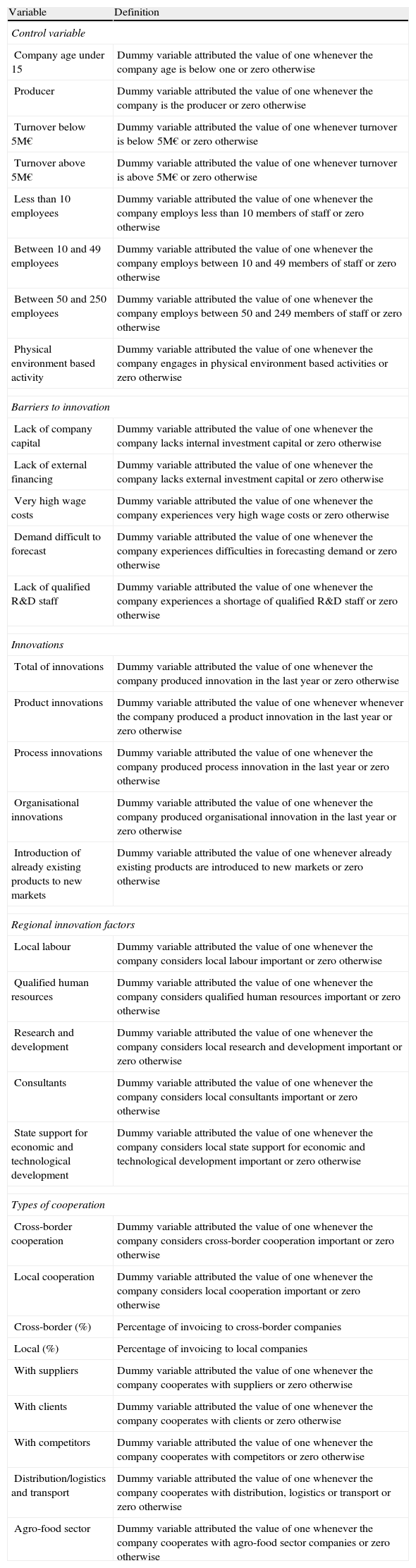

Effects of cooperation on company turnoverTable 4 presents the results deriving from determining the factors influencing regional business volumes. The results of the F tests indicate that the model is significantly able to calculate the percentage of local turnover volume [F(9.61)=2.23; p<.05] while failing to attain this significance for cross-border turnover percentages [F(9.61)=0.53; p≥.05]. In the first model, we find that 28.3% of the variance in turnover invoiced to local company is explained by the independent variables while this proportion falls to 8.5% for invoicing sent to cross-border companies.

Bivariate regression model of percentage of turnover invoiced to local and to cross-border companies.

| Local | Cross-borders | |||

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Portugal | −1.51 | 1.65 | 5.22 | 1.19 |

| Innovations | 2.32 | 1.59 | −0.05 | 1.15 |

| Cooperation w/suppliers | −0.52 | 1.39 | −0.17 | 1.01 |

| Cooperation w/clients | −0.58 | 1.60 | −8.37 | 1.16 |

| Cooperation w/competitors | 1.66 | 1.48 | 6.23 | 1.07 |

| Very high wage costs | −1.15 | 0.70 | 7.78 | 5.09 |

| Demand difficult to forecast | 1.56** | 0.53 | −2.82 | 3.83 |

| Qualified human resources | −0.05 | 0.51 | −1.74 | 3.68 |

| Research and development | −1.03 | 0.54 | 2.43 | 3.94 |

| Constant | 2.59 | 2.59 | 2.57 | 18.74 |

| N | 61 | 61 | ||

| F test | 2.23* | 0.53 | ||

| R Squared | 0.283 | 0.085 | ||

| Breusch–Pagan test | 0.003 | |||

Output STATA software.

In terms of invoices to local companies, only those firms referring to demand being difficult to forecast (B=−1.56; p<.01) return a significantly greater percentage of turnover deriving from local companies. As regards cross-border invoicing, no statistically significant influence was observed (p≥.05) among the independent variables for invoice turnover percentage. The Breusch–Pagan test [χ2(1)=0.003; p≥.05] did not find any statistically significant correlation between the local invoice and cross-border invoice models. Thus, these results only back research hypothesis H1a: Local co-operation positively impacts on the firm's performance. As has been advocated by Baum et al. (2000), cooperation activities are once again found to have a positive impact on company financial performance. However, only local cooperation generates this effect.

Final considerationsThe present study, focusing on regions on either side of the border between Portugal and Spain, carried out analysis of empirical data obtained from a sample of companies from the two countries in the agro-food and logistics/transport sectors. This study of the probability of cooperation between companies made recourse to Probit model estimates. The final cross-border firm model demonstrates a strong predictive capacity of the overall performance of small and medium sized companies engaged in such cooperation.

Local cooperation and cross-border cooperation, while registering different characteristics, return positive impacts on company innovation rates. The main determinants of local cooperation prove to be: cooperation with suppliers, high wage costs and access to qualified human resources. Furthermore, we found the Portuguese SMEs among the sample studied reported a greater propensity to undertake cooperation processes than their Spanish peers. Finally, the level of influence held by cooperation activities over company financial performance returns a positive impact in terms of local cooperation.

In keeping with the rising tide of competitive pressures faced by companies, SME business managers should seek to develop strategies that enable not only their own survival but also the company's continuous development. The development of European policies in terms of facilitating the free circulation of persons, goods and capital provided for the appearance of business models based on cooperation between companies from different countries, particularly in bordering regions sharing similar characteristics.

This cooperation may enable, and especially for SMEs, the leveraging of critical mass driving opportunities generated by accessing new markets, new sources of supply, introducing marketplace innovations and attaining a higher level of overall company performance.

The identification of regional factors enabling and hindering cooperation among SMEs generates worthwhile indicators for public innovation support policies as they may now be tailored to take into account the specific properties of companies actually located in the border regions under study. However, we do believe this research needs replicating involving a larger sample of cross border firms.

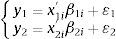

| Variable | Definition |

| Control variable | |

| Company age under 15 | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company age is below one or zero otherwise |

| Producer | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company is the producer or zero otherwise |

| Turnover below 5M€ | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever turnover is below 5M€ or zero otherwise |

| Turnover above 5M€ | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever turnover is above 5M€ or zero otherwise |

| Less than 10 employees | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company employs less than 10 members of staff or zero otherwise |

| Between 10 and 49 employees | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company employs between 10 and 49 members of staff or zero otherwise |

| Between 50 and 250 employees | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company employs between 50 and 249 members of staff or zero otherwise |

| Physical environment based activity | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company engages in physical environment based activities or zero otherwise |

| Barriers to innovation | |

| Lack of company capital | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company lacks internal investment capital or zero otherwise |

| Lack of external financing | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company lacks external investment capital or zero otherwise |

| Very high wage costs | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company experiences very high wage costs or zero otherwise |

| Demand difficult to forecast | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company experiences difficulties in forecasting demand or zero otherwise |

| Lack of qualified R&D staff | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company experiences a shortage of qualified R&D staff or zero otherwise |

| Innovations | |

| Total of innovations | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company produced innovation in the last year or zero otherwise |

| Product innovations | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever whenever the company produced a product innovation in the last year or zero otherwise |

| Process innovations | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company produced process innovation in the last year or zero otherwise |

| Organisational innovations | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company produced organisational innovation in the last year or zero otherwise |

| Introduction of already existing products to new markets | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever already existing products are introduced to new markets or zero otherwise |

| Regional innovation factors | |

| Local labour | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers local labour important or zero otherwise |

| Qualified human resources | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers qualified human resources important or zero otherwise |

| Research and development | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers local research and development important or zero otherwise |

| Consultants | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers local consultants important or zero otherwise |

| State support for economic and technological development | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers local state support for economic and technological development important or zero otherwise |

| Types of cooperation | |

| Cross-border cooperation | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers cross-border cooperation important or zero otherwise |

| Local cooperation | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company considers local cooperation important or zero otherwise |

| Cross-border (%) | Percentage of invoicing to cross-border companies |

| Local (%) | Percentage of invoicing to local companies |

| With suppliers | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company cooperates with suppliers or zero otherwise |

| With clients | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company cooperates with clients or zero otherwise |

| With competitors | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company cooperates with competitors or zero otherwise |

| Distribution/logistics and transport | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company cooperates with distribution, logistics or transport or zero otherwise |

| Agro-food sector | Dummy variable attributed the value of one whenever the company cooperates with agro-food sector companies or zero otherwise |