Although bacteraemia has been reported to be related to false positive results in the 1,3-beta-d-glucan (BDG) test, the evidence for this interaction is limited.

AimsTo investigate the association between bacteraemia and the BDG test.

MethodsRecords of the Infection Control Committee were reviewed to identify bacteraemia in patients who were hospitalized in the haematology ward and stem cell transplantation unit. Patients who had undergone the BDG test at least once within 5 days of a positive blood culture were included in the study. BDG levels in the sera were assayed using the Fungitell kit (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The cutoff for BDG positivity was 80pg/mL.

ResultsEighty-three bacteraemic episodes were identified in 71 patients. BDG positivity was detected in 14 patients with bacteraemia, and only 1 patient with Escherichia coli bacteraemia had high BDG levels (over 80pg/mL) despite having no evidence of invasive fungal infection (IFI).

ConclusionsOur study suggests that the cross-reactivity of the BDG test with a concomitant or recent bacteraemia is a very rare condition. Patients with risk factors for IFI should be evaluated cautiously when a positive BDG test is reported.

Aunque se ha descrito que la bacteriemia se relaciona con resultados falsos positivos en la determinación de 1,3-beta-d-glucano (BDG), las pruebas de esta interacción son limitadas.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este estudio fue investigar la asociación entre la bacteriemia y la determinación de BDG.

MétodosPara identificar a los pacientes con bacteriemia hospitalizados en la sala de hematología y la unidad de trasplante de células progenitoras, se revisaron los archivos de historias clínicas del comité de control de infecciones. En el estudio se incluyeron a los pacientes sometidos como mínimo a una determinación de BDG al cabo de 5 días de un resultado positivo del hemocultivo. La determinación de los valores séricos de BDG se analizó con el test Fungitell (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA, EE. UU.), de acuerdo con las especificaciones del fabricante. El punto de corte para la determinación de un resultado positivo se estableció en 80pg/mL.

ResultadosSe identificó un total de 83 episodios de bacteriemia en 71 pacientes. En 14 de ellos, la determinación de BDG fue positiva, pero sólo se identificaron valores elevados en un paciente con bacteriemia por Escherichia coli (>80pg/mL), a pesar de que no se detectaron pruebas de infección fúngica invasora (IFI).

ConclusionesLos resultados del presente estudio sugieren que la reactividad cruzada entre la determinación de BDG y con una bacteriemia concomitante o reciente es excepcional. Cuando se documenten resultados positivos de la determinación de BDG, es preciso valorar con precaución a los pacientes con factores de riesgo de IFI.

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) remain a major cause of mortality, particularly in patients with haematological malignancies and those who have undergone stem cell transplantation.2 More than 10 years ago the measurement of 1,3-beta-d-glucan (BDG) level, a cell wall component of Aspergillus, Candida, and Pneumocystis, was introduced to aid the diagnosis of IFI, and it was included as a diagnostic criterion in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group (EORTC-MSG) IFI definitions in 2008.3,9 The sensitivity of the BDG assay mainly depends on patient characteristics, preferred cutoff value, and sampling schedule.2

Since diagnostic interventions and therapeutic decisions can be made on the basis of BDG test results, physicians dealing with the treatment of IFI should be aware of the potential causes of false positivity (positive findings not related to IFI).

Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (OPGs) are a family of oligosaccharides found in the periplasm of gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli.7,8 Although no cross-reactivity has been reported in the prospective validation studies of commercial BDG assays in patients with bacteraemia,14,15,19 BDG reactivity was reported in the plasma samples of 2 out of 9 patients with haematologic malignancies and Pseudomonas bacteraemia and in 1 out of 5 patients with Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteraemia. The plasma samples in these patients were obtained on the same day on which blood culture was performed.11 When the cross-reactivity of BDG was tested with supernatants of several bacterial species, only P. aeruginosa and S. pneumoniae supernatants showed BDG levels >80pg/mL. Other than in the instances cited above, the evidence for cross-reactivity of BDG with bacteraemia is limited to small case series or retrospective case analyses.1,6,13,17

We aimed to investigate the interaction between bacteraemia and BDG positivity in patients with haematological malignancies or stem cell transplantation in a “real life” clinical setting in which the BDG assay is used in patients with risk factors for IFI.

This study was conducted at the Erciyes University Hospital, a 1300-bed tertiary care centre in Kayseri, Turkey. The study was approved by the ethics board of the Medical Faculty. The records of the Infection Control Committee were reviewed to identify the patients with bacteraemia who were hospitalized in the haematology ward and stem cell transplantation unit. All medical records, laboratory data, and discharge summaries were evaluated to identify the cases. Patients who had at least one BDG measurement within 5 days after a positive blood culture were enrolled in the study. Patients with polymicrobial bacteraemia episodes were excluded. Blood cultures positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci without any proven risk factors were considered to be contaminated and were not included in the study.18

BDG levels in sera were assayed using the Fungitell kit (Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The cutoff value for BDG positivity was set at 80pg/mL.4 The presence of IFI was classified as proven, probable or possible on the basis of the criteria established by the EORTC-MSG (independently of BDG results).3

Between August 2008 and January 2011, 83 bacteraemia episodes (E. coli, 33; Klebsiella pneumoniae, 16; Klebsiella oxytoca, 2; Enterobacter cloacae, 1; Salmonella enteritidis, 1; P. aeruginosa, 8; Acinetobacter baumannii, 3; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, 2; Staphylococcus epidermidis, 6; Enterococcus faecium, 6; Staphylococcus aureus, 4; and S. pneumoniae, 1) were identified in 71 patients. The median age of the patients was 39 years (range: 17–76 years), and 44 of them were male. The most common underlying disease was acute myelogenous leukaemia in 26 patients, followed by non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 13 patients. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia was present in 7 patients, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in 2, Hodgkin lymphoma in 2 patients, multiple myeloma in 3 patients, aplastic anaemia in 3 patients, myelodysplastic syndrome in 1 patient and testis tumour in 1 patient. Eleven out of 71 patients underwent allogenic stem cell transplantation (SCT) and three underwent autologous SCT. BDG measurement was performed on the same day as the blood culture in 34 bacteraemia episodes; in 25 episodes, it was performed 1 day later; in 9 episodes, 2 days later; in 9 episodes, 3 days later; in 5 episodes, 4 days later; and 1 episode, 5 days later.

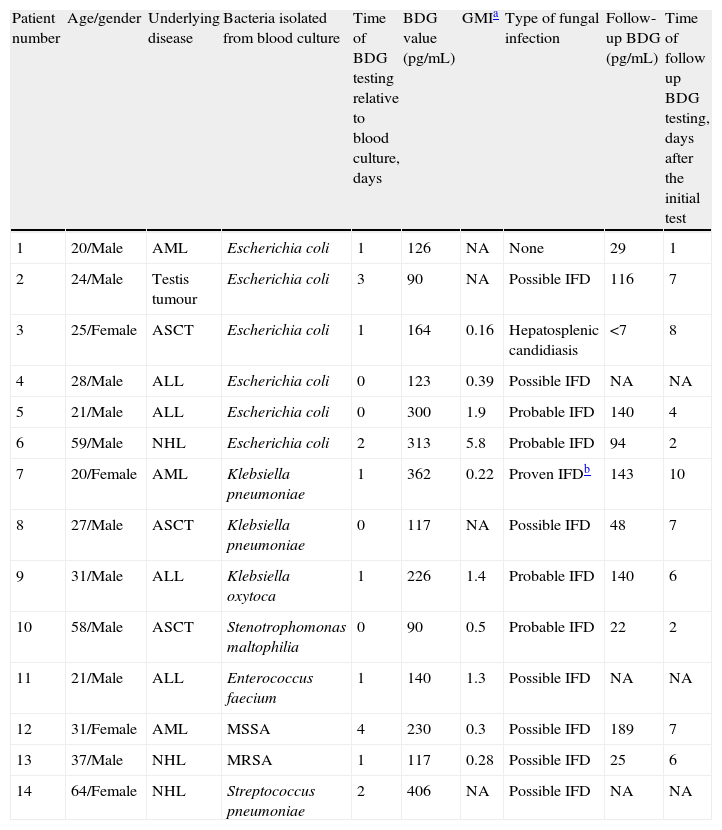

BDG positivity was detected in 6 patients with E. coli bacteraemia, 2 with K. pneumoniae bacteraemia, 1 with K. oxytoca bacteraemia, and 1 with S. maltophilia bacteraemia. Of the 10 patients, only 1 (patient 1) had high BDG levels (over 80pg/mL) despite showing no evidence of IFI (Table 1). When we analyzed the gram-positive bacteraemia episodes, 2 patients with S. aureus bacteraemia, 1 patient with E. faecium, and 1 patient with S. pneumoniae bacteraemia had positive BDG results. However, all the patients had probable or possible IFI according to EORTC-MSG criteria and received anti-fungal therapy. BDG levels decreased under antifungal therapy in all patients who had a follow-up test, except in the case of one patient (Table 1).

Characteristics of the patients with bacteraemia who rendered a positive 1,3-beta-d-glucan test (all patients were neutropenic for longer than 7 days and they had radiologic signs of invasive fungal infection).

| Patient number | Age/gender | Underlying disease | Bacteria isolated from blood culture | Time of BDG testing relative to blood culture, days | BDG value (pg/mL) | GMIa | Type of fungal infection | Follow-up BDG (pg/mL) | Time of follow up BDG testing, days after the initial test |

| 1 | 20/Male | AML | Escherichia coli | 1 | 126 | NA | None | 29 | 1 |

| 2 | 24/Male | Testis tumour | Escherichia coli | 3 | 90 | NA | Possible IFD | 116 | 7 |

| 3 | 25/Female | ASCT | Escherichia coli | 1 | 164 | 0.16 | Hepatosplenic candidiasis | <7 | 8 |

| 4 | 28/Male | ALL | Escherichia coli | 0 | 123 | 0.39 | Possible IFD | NA | NA |

| 5 | 21/Male | ALL | Escherichia coli | 0 | 300 | 1.9 | Probable IFD | 140 | 4 |

| 6 | 59/Male | NHL | Escherichia coli | 2 | 313 | 5.8 | Probable IFD | 94 | 2 |

| 7 | 20/Female | AML | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | 362 | 0.22 | Proven IFDb | 143 | 10 |

| 8 | 27/Male | ASCT | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0 | 117 | NA | Possible IFD | 48 | 7 |

| 9 | 31/Male | ALL | Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 | 226 | 1.4 | Probable IFD | 140 | 6 |

| 10 | 58/Male | ASCT | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 0 | 90 | 0.5 | Probable IFD | 22 | 2 |

| 11 | 21/Male | ALL | Enterococcus faecium | 1 | 140 | 1.3 | Possible IFD | NA | NA |

| 12 | 31/Female | AML | MSSA | 4 | 230 | 0.3 | Possible IFD | 189 | 7 |

| 13 | 37/Male | NHL | MRSA | 1 | 117 | 0.28 | Possible IFD | 25 | 6 |

| 14 | 64/Female | NHL | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2 | 406 | NA | Possible IFD | NA | NA |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukaemia; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; BDG, 1,3-beta-d-glucan; GMI, galactomannan index; IFD, invasive fungal disease; MSSA, methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NA, not available; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Albert et al.1 detected 16 false-positive BDG results in the sera of 39 bacteraemia patients without fungal infection. However, presence of several clinical and laboratory circumstances related to false positivity of BDG assay such as haemodialysis (in 3 patients), recent surgery (in 6 patients) and haemolysis in serum samples (in 2 patients) limit the interpretation of the results of their interesting study. According to Albert's findings, serum BDG was >80pg/mL in 8 out of 15 patients presenting with E. coli bacteraemia and in 3 out of 8 patients presenting with S. aureus bacteraemia. However, Mennink-Kersten et al.11 did not determine BDG in culture supernatants of E. coli and S. aureus.

In our study, only 1 patient with E. coli bacteraemia presented a BDG concentration >80pg/mL without evidence of IFI (Table 1). Computerized tomography of thorax of this patient showed completely normal results and the fever resolved with anti-bacterial therapy. Since the patient had not received albumin or immunoglobulin and had not undergone haemodialysis, we could also exclude these potential sources of false positivity. The patient was on imipenem therapy, but a previous study showed no positive reaction between imipenem and BDG assay.10 The BDG level was 126pg/mL and decreased to 29pg/mL one day later without any antifungal therapy. Such abrupt fluctuations in BDG levels were reported to be an indicator of false positivity.12,16 False-positive BDG results have been described after contamination by environmental BDG.5 Serum samples may be contaminated with fungal spores during several manipulations in the laboratory.

In contrast with previous case reports,6,11 we did not observe cross-reactivity of Fungitell assay in sera of patients with P. aeruginosa bacteraemia. Three out of 8 serum samples with a BDG level <80pg/mL were taken on the same day as the blood cultures. In the study that showed the presence of BDG in patients with P. aeruginosa bacteraemia, bacteria were cultured in human serum supplemented with glucose for 72h at 120rpm and 37°C, which is a non-conventional method to obtain bacterial supernatants.11 While this method was successful in an experimental study showing the presence of BDG in P. aeruginosa, in our opinion, its relation to ‘real-life’ cross-reactivity is limited. Four patients with P. aeruginosa bacteraemia whose serum had a BDG concentration higher than 80pg/mL were reported in a recent study.1 However, 3 patients had known risk factors (haemodialysis, recent digestive tract surgery and haemolysed serum in each patient) related to false positivity of BDG assay.1

In conclusion, our findings suggest that concurrent or recent bacteraemia very rarely leads to BDG reactivity. In these cases, other potential causes of false positivity should be ruled out, such as haemodialysis with cellulose membranes, treatment with immunoglobulin, albumin, or other blood products filtered through BDG-containing cellulose filters, serosal exposure to glucan-containing gauze and administration of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.9 When these potential causes have been excluded, high serum BDG levels may be indicative of IFI and require additional diagnostic efforts.