Few scientific studies have evaluated dermatophytosis among children in the state of Amazonas or in the greater northern region of Brazil.

AimsThe aim of this study was to research the frequency and aetiology of dermatophytosis in children age 12 and under, who were seen between March 1996 and November 2005 at the Mycology Laboratory of the National Institute of Amazonian Research.

MethodsFor mycological diagnoses, epidermal scales and/or hairs were used. A portion of this material was treated with potassium hydroxide for direct examination, and another portion was cultivated in Mycobiotic Agar for the isolation of dermatophytes.

ResultsOf the 590 samples analysed, 210 showed positive diagnoses by direct examination and cultivation. Tinea capitis (153 cases) was the most frequent type of dermatophytosis, and Trichophyton tonsurans (121 cases) was the most frequently isolated fungal agent. Tinea corporis was observed in 48 cases where the most frequently isolated fungal agent was also T. tonsurans (17 cases), and the corporal regions most affected were the face, arms and trunk. The laboratory confirmed tinea pedis in 6 cases, and the principal fungal agents isolated were Trichophyton rubrum (3) and Trichophyton mentagrophytes (3). The presence of tinea cruris was confirmed in 3 cases, and T. rubrum, T. tonsurans and Epidermophyton floccosum were isolated from these cases.

ConclusionsThe children examined were primarily affected by tinea capitis, and the main fungal agent for this dermatophytosis was T. tonsurans.

Apenas se dispone de estudios científicos que hayan investigado las dermatofitosis en niños que viven en el estado de Amazonas o en la región más septentrional de Brasil.

ObjetivosEl objetivo de este estudio fue investigar la frecuencia y la etiología de las dermatofitosis en niños de 12 años de edad o menores, que fueron examinados entre marzo de 1996 y noviembre de 2005 en el Laboratorio de Micología del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones de Amazonia.

MétodosPara el diagnóstico micológico, se utilizaron muestras de escamas epidérmicas y/o cabello. Una parte de la muestra se trasladó a un portaobjetos y se añadió una solución de hidróxido de potasio para examen microscópico directo. La otra parte de la muestra se sembró en medio de cultivo (Mycobiotic Agar) para el aislamiento de los dermatofitos.

ResultadosDe las 590 muestras analizadas, en 210 se aislaron dermatofitos mediante examen microscópico directo y cultivo. La tiña del cuero cabelludo (153 casos) fue la dermatofitosis más frecuente, y Trichophyton tonsurans (121 casos) fue el patógeno aislado más habitual. En 48 casos se detectó tiña corporal, siendo también T. tonsurans el hongo aislado más frecuente (17 casos), y las regiones corporales más afectadas fueron la cara, extremidades superiores y tronco. El laboratorio confirmó un pie de atleta en 6 casos y los principales hongos aislados fueron Trichophyton rubrum (3) y Trichophyton mentagrophytes (3). La tiña crural solo se confirmó en 3 casos, en los que se aislaron T. rubrum, T. tonsurans y Epidermophyton floccosum.

ConclusionesEn los niños examinados, la tiña del cuero cabelludo fue la afectación principal y el patógeno responsable de estas dermatofitosis fue T. tonsurans.

Dermatophytoses are superficial fungal infections of keratinized tissues that are caused by a group of fungi called dermatophytes. These fungi belong to the genera Epidermophyton, Microsporum and Trichophyton.1,2 Dermatophytes are classified as anthropophilic (human), geophilic (soil) or zoophilic (animal) according to their normal habitat. Dermatophytes from each of these three groups can cause infection in humans, but their reservoirs have important epidemiological implications for infection, including the infected site and the distribution of the infection.3

The distribution of dermatophytes varies by region2–7 which is influenced by factors such as climatic variation, socio-economic status, contact with domestic animals and the age of the population.

With respect to the epidemiological characteristics of the clinical forms of dermatophytosis worldwide, the following relationships can be drawn: (a) tinea capitis is the most frequent clinical form in patients less than 12 years old; (b) tinea cruris is limited to adolescent and young adult males; (c) tinea pedis is not commonly seen in children and is rarely seen in individuals between 2 and 4 years old; and (d) dermatophytes rarely infect neonates.1,2

In general, health professionals in the state of Amazonas-Brazil tend to believe that the frequency of people affected by dermatophytosis is greater in the northern region of Brazil than in the other regions of the country. The climatic and sanitary conditions, as well as the sub-standard medical treatment, present throughout the Amazon region, are important factors. Furthermore, few studies have evaluated the frequency and aetiology of dermatophytosis in children, and no studies have been published on this issue in the state of Amazonas and the northern region of Brasil.

The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency and aetiology of dermatophytosis in children age 12 and under who were seen over a period of 10 years at the Laboratory of Mycology of the National Institute for Amazon Research (INPA).

MethodsFrom March 1996 to November 2005, 590 children (12 years of age and under) were seen at the Mycology Laboratory of the Research Coordination of Health Sciences at INPA.

The biological samples used for the laboratory diagnosis were obtained from skin lesions, nails and the scalp. All samples were submitted to direct investigation by microscopy (the biological material was clarified with 30% potassium hydroxide) and were inoculated onto Sabouraud agar with chloramphenicol and cycloheximide (Mycobiotic Agar, DIFCO, Detroit, MI, USA) and incubated at 27–28°C.8

The identification of the cultured fungal agent was based on macro- and micromorphological characteristics.9,10 Cultures were considered negative if there was no fungal growth after 15 days in culture.

In this study, the clinical forms of dermatophytosis observed included tinea capitis, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea pedis and tinea unguium.3

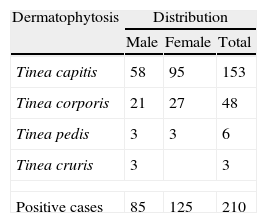

ResultsAmong the 590 suspected cases of dermatophytosis, 210 (35.6%) were culture positive thereby confirming the diagnosis. Table 1 shows the occurrence of dermatophytosis by clinical forms and sex.

With respect to the distribution of the clinical forms of dermatophytosis, 72.9% of cases were tinea capitis, 22.9% were tinea corporis, 2.9% were tinea cruris and 1.4% were tinea pedis (Table 1).

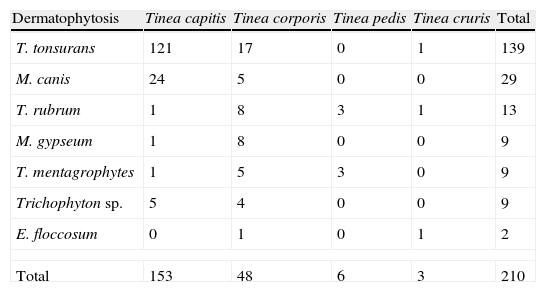

Tinea capitis affected a higher number of females (95 cases) than males (58), however, the statistical test of chi-square with Yates’ correction demonstrated that this difference was not significant (P-value 0.2784) (Table 1). The two main causative agents were Trichophyton tonsurans (121 cases) and Microsporum canis (24 cases) (Table 2).

Dermatophytes isolated from different types of tinea infection.

| Dermatophytosis | Tinea capitis | Tinea corporis | Tinea pedis | Tinea cruris | Total |

| T. tonsurans | 121 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 139 |

| M. canis | 24 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| T. rubrum | 1 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 13 |

| M. gypseum | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Trichophyton sp. | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| E. floccosum | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 153 | 48 | 6 | 3 | 210 |

Tinea corporis had the second highest rate of occurrence, and the percentage of affected patients was similar for both sexes. The main corporal regions affected were the face (32%), trunk (31%), arms (23%), legs (19%) and neck (7%). T. tonsurans was the predominant fungal agent identified (17 cases) followed by Trichophyton rubrum (8 cases), Microsporum gypseum (8 cases), M. canis (5 cases) and T. mentagrophytes (5 cases) (Table 2).

The laboratory confirmed 6 cases of tinea pedis, and the main agents were T. rubrum (3 cases) and T. mentagrophytes (3 cases). Tinea cruris was confirmed in 3 cases.

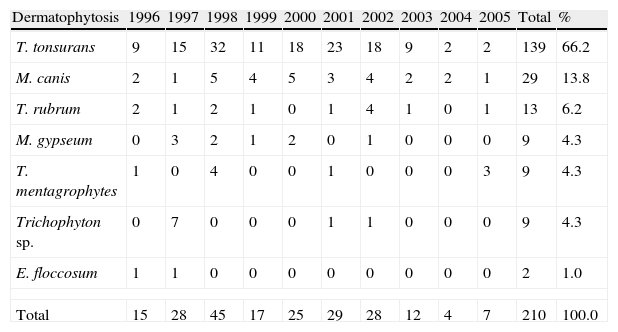

The annual occurrences of the dermatophyte species isolated from cases of dermatophytosis are presented in Table 3. From the 210 dermatophytes identified, T. tonsurans had the highest incidence (139 cases, 66.2%), followed by M. canis (29 cases, 13.8%). The causative agents for dermatophytosis showed similar occurrence rates over the years of the study (Table 3).

Annual occurrence of the different dermatophyte species.

| Dermatophytosis | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | Total | % |

| T. tonsurans | 9 | 15 | 32 | 11 | 18 | 23 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 139 | 66.2 |

| M. canis | 2 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 29 | 13.8 |

| T. rubrum | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 6.2 |

| M. gypseum | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4.3 |

| T. mentagrophytes | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 4.3 |

| Trichophyton sp. | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4.3 |

| E. floccosum | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Total | 15 | 28 | 45 | 17 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 210 | 100.0 |

In this study, 35.6% (n=210) of cases were positive for dermatophytes. In other studies, this percentage has varied from 20.7% to 64.6%.11–14 These variations may be attributable to the following variables: (a) the clinical form of dermatophytosis; (b) the number of patients previously treated; (c) the experience of the dermatologists; (d) the level of training of the microscopists; (e) laboratory conditions; and (f) the species of dermatophyte most prevalent.13

Concerning the epidemiology of infection, several studies have shown that dermatophytosis occurs most frequently in children who are 12 years and younger,1,2,11,13 which can be attributed to factors such as inadequate personal hygiene habits, high density in schools and daycare centres, direct contact with domestic animals, contact with sand, immature immune responses and the absence of protective factors in the skin.13

Concerning the clinical forms of ringworm, tinea capitis is the most common form in children.2,15,16 It presents as a superficial infection of the scalp, eyebrows and eyelashes; it mainly affects the follicles and hair shaft and is caused by species of the genera Trichophyton and Microsporum.2 Furthermore, this form of tinea is transmitted by animals or other children.11,17 Worldwide, the main causative agent for tinea capitis is M. canis.2,11,18 However, in northern, midwestern and northeastern Brazil, T. tonsurans is the main causative agent for this infection.12-14,19,20

The data from this study agree with the published literature; of the 210 cases of dermatophytosis that were detected, 153 were tinea capitis, and 121 of these cases were caused by T. tonsurans (Tables 1 and 2). This anthropophilic species was originally brought to the Americas during colonization, and has become cosmopolitan and now causes endothrix infections and small outbreaks in schools, preschools and nursing homes.19,21

Tinea corporis is the most common clinical form of dermatophytosis in adults.1-3 In this study specifically looking at children, tinea corporis was the second most frequent form (48 cases). The body areas most commonly affected were the thorax, the arms, and the legs. In the present work, the main causative agents of the clinical form were T. tonsurans, M. gypseum and T. rubrum, a new finding in this age group. Other studies have shown T. rubrum to be the main agent causing dermatophytosis.19,22 Tinea pedis was detected in only six cases, and this low frequency is confirmed by the results of other studies.13,23T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes were the main fungal agents. Specifically, in the Amazon region, wearing closed shoes can create a moist environment that facilitates the growth of dermatophytes, whereas open shoes can inhibit the development of tinea pedis.

Although few cases of tinea cruris were diagnosed, the fungal agents T. rubrum, T. tonsurans and E. floccosum were identified. This low incidence of tinea cruris was also reported in previous studies.2,23

Studies reported in the literature have shown that the frequencies of the causative agents for dermatophytoses change over time.19 In the United States, Microsporum audouinii and M. canis were the main causative agents of tinea capitis until the 1970s. However, studies between 1970 and 1990 showed that T. tonsurans was responsible for approximately 90% of these cases.21 In the present study, however, no changes in the occurrence of the dermatophytes was observed in almost one decade. T. tonsurans, M. canis and T. rubrum were the most frequently isolated fungal species in children.

It is important to remark that during this long period of the study no cases of superficial mycoses caused by Scytalidium spp., Aspergillus spp. or Scopulariopsis spp. were noted in children. These agents were only isolated in our laboratory as causative agents of nail infections in adults.

Authors’ declarationWe are taking the opportunity to declare that: (a) the contents of the article are original and they were not published previously; (b) there is no conflict of interests, related to financial aspects; (c) all the authors have read and approved this manuscript; and (d) this work was previously submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of National Institute of Amazonian Research.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors are grateful to Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia (MCT-INPA) for the financial support.