Cryptococcosis is a rare, sporadic mycosis that affects a wide variety of animals worldwide. It is caused by some yeasts belonging to basidiomycetes and grouped in the Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii species complexes, whose speciation has been controversial for many years. In the last taxonomic review, based mainly on the phylogenetic analyses of these species complexes, it has been proposed to divide C. neoformans into two species and C. gattii into five, also describing the presence of different hybrids.3

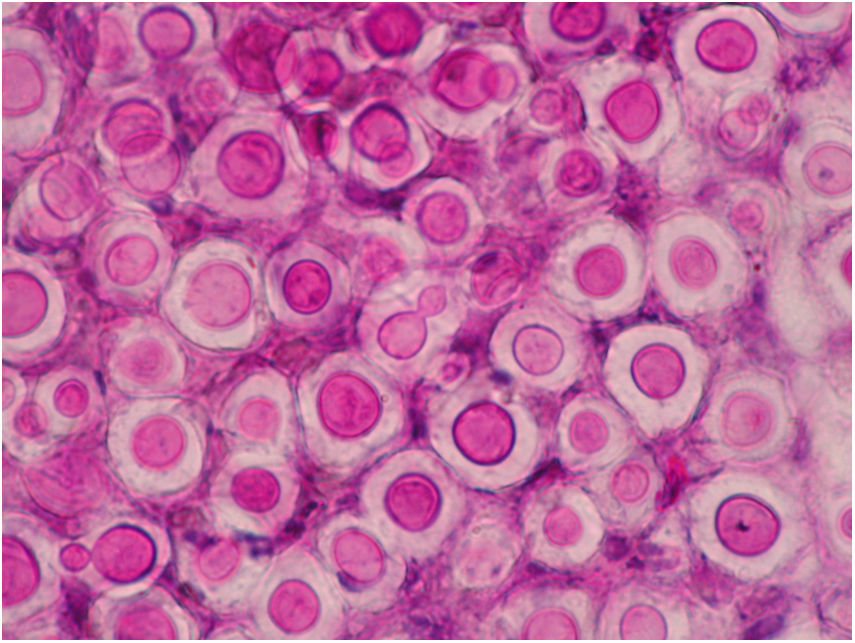

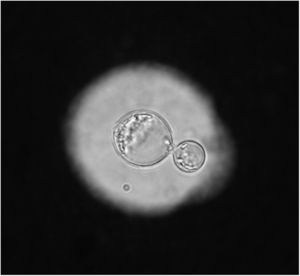

In domestic animals the infection starts in the nasal cavity after yeast inhalation. In cats and dogs it usually spreads to the respiratory system and the central nervous system, and skin forms are also found in advanced cases. Although rare, cryptococcosis is the most common systemic mycosis in cats. Treatment usually combines surgical resection of granulomas and treatment with antifungals. In horses, sheep and goats it usually affects the respiratory system, while in cows it is usually a localized infection at the mammary gland.1 Cytological examination of aspirates obtained from lymph nodes, nodules or cerebrospinal fluid, among other samples, allows the visualization of the characteristic capsule in these yeasts (Fig. 1). Although these species grow well in the common culture media used in mycology, their identification at the species level is difficult, requiring the use of various DNA techniques (e.g. AFLP, MLST, RFLP) to define the different molecular types.

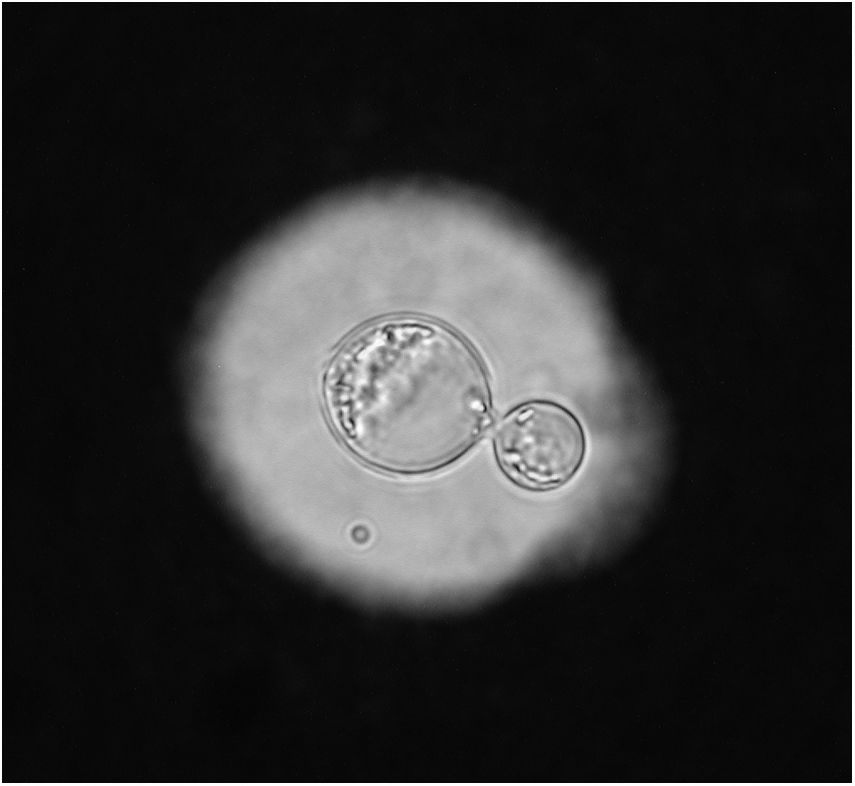

In dogs and cats, the most frequently isolated species is C. neoformans, which includes the molecular types VNI-VNII/AFLP1. The new species Cryptococcus deneoformans (VNIV/AFLP2) is isolated to a lesser extent. The droppings of pigeons and other birds are an important environmental reservoir of both species. Until the end of the 20th century, the majority of cases in dogs and cats were related to infections caused by the C. neoformans complex. This complex has ubiquitous distribution and is considered an opportunistic pathogen that causes disease mainly in immunocompromised patients (Fig. 2). In fact, with the exception of those described in Australia where the C. gattii complex is widely distributed, cases caused by strains belonging to this complex were rarely found in the literature. The species of the C. gattii complex are primary pathogens considered endemic to tropical and subtropical regions, being present in nature in soils and numerous tree species. However, in the last two decades, several infections due to strains of the C. gattii complex have occurred in different animal species living in temperate zones of other continents, such as Europe or the Americas. There are different hypotheses that could explain this change in the etiology of cryptococcosis, such as the shipment of eucalyptus trees from Australia, the global warming, ocean and wind currents, the movement of animals and, surprisingly, tsunamis.2 Concerning the last case, a tsunami that occurred in the middle of the last century and damaged certain areas of the north-western coast of Canada and the United States could be the cause of the introduction of some strains of the C. gattii complex common of warmer areas. These strains would have arrived by shipborne transport from South America, possibly in their ballast water.

Although we do not know the global distribution of the new species, C. gattii (VGI/AFLP4), Cryptococcus deuterogattii (VGII/AFLP6) and Cryptococcus bacillosporus (VGIII/AFLP5) are less frequently isolated from cases of cryptococcosis in dogs and cats. However, C. deuterogattii was the main responsible for the 1999 outbreak of human cryptococcosis on Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada), which also affected dogs and cats. This species has also been isolated in different states in the Pacific Northwest region of the USA. It also appears that C. bacillosporus is frequently isolated from cases of feline cryptococcosis in California, USA, but not from dogs. Finally, Cryptococcus tetragattii (VGIV/AFLP7) and Cryptococcus decagattii (AFLP10) are rare species and their presence in these animals is currently unknown.

Conflict of interestAuthor has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).