Cryptococcal ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection is known to occur due to an underlying infection in the patient rather than by nosocomial transmission of Cryptococcus during shunt placement. A case of chronic hydrocephalus due to cryptococcal meningitis that was misdiagnosed as tuberculous meningitis is described.

Case reportPatient details were extracted from charts and laboratory records. The identification of the isolate was confirmed by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the orotodine monophosphate pyrophosphorylase (URA5) gene. Antifungal susceptibility was determined using the CLSI M27-A3 broth microdilution method. Besides, a Medline search was performed to review all cases of Cryptococcus ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection. Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto (formerly Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii), mating-type MATα was isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid and external ventricular drain tip. The isolate showed low minimum inhibitory concentrations for voriconazole (0.06mg/l), fluconazole (8mg/l), isavuconazole (<0.015mg/l), posaconazole (<0.03mg/l), amphotericin B (<0.06mg/l) and 5-fluorocytosine (1mg/l). The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate, but died of cardiopulmonary arrest on the fifteenth postoperative day.

ConclusionsThis report underlines the need to rule out a Cryptococcus infection in those cases of chronic meningitis with hydrocephalus.

La infección criptocócica por contaminación de las derivaciones ventriculoperitoneales es una complicación que puede tener lugar en el paciente previamente infectado más que deberse a una transmisión nosocomial de Cryptococcus durante la colocación del dispositivo. Se describe un caso de hidrocefalia crónica por meningitis criptocócica que se diagnosticó erróneamente como meningitis tuberculosa.

Caso clínicoLos datos del paciente se extrajeron de la historia clínica y de los registros de laboratorio. La identificación del aislamiento se confirmó mediante PCR de polimorfismo de longitud de fragmento de restricción del gen de la orotodina monofosfato pirofosforilasa (URA5). La sensibilidad a los antifúngicos se realizó mediante el método de microdilución en caldo CLSI M27-A3. Se realizó, además, una búsqueda en Medline para revisar todos los casos de infección por Cryptococcus asociados a derivación ventriculoperitoneal. Se aisló Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto (antes Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii), tipo MATα, del líquido cefalorraquídeo y de la punta del drenaje extraventricular. El aislamiento mostró, in vitro, valores bajos de concentración mínima inhibitoria para el voriconazol (0,06mg/l), el fluconazol (8mg/l), el isavuconazol (<0,015mg/l), el posaconazol (<0,03mg/l), la anfotericina B (<0,06mg/l) y la 5-fluorocitocina (1mg/l). El paciente fue tratado con anfotericina B desoxicolato intravenoso, pero falleció por parada cardiopulmonar el decimoquinto día del postoperatorio.

ConclusionesNuestro caso subraya la necesidad de descartar la presencia de Cryptococcus en los casos de meningitis crónica con hidrocefalia.

Cryptococcosis is an invasive fungal infection with an increasing prevalence in immunocompromised hosts.17 The two varieties within Cryptococcus neoformans were raised to the species level in 2015 — Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii as Cryptococcus neoformans sensu stricto, and Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans as Cryptococcus deneoformans.11 Furthermore, five species within the Cryptococcus gattii species complex were identified. The decayed wood of several trees worldwide is the main environmental niche for the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex.17

C. neoformans and C. deneoformans typically infect people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), while the C. gattii complex causes disease in apparently healthy individuals.8,11 Cryptococcal infections also occur in immunodeficient hosts with diabetes, cancer, haematological malignancies, solid organ transplant, sarcoidosis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and long-term steroid therapy. Clinically and radiologically, systemic cryptococcosis can masquerade as tuberculosis. In countries such as India, where tuberculosis is hyperendemic, cryptococcal meningitis is not considered in cases of chronic meningitis and, by default, patients are treated for tuberculous meningitis. Conditions such as brain tumor, cerebral stroke, and enteric fever can mimic cryptococcal meningitis.12,14 It also must be distinguised from pyogenic and aseptic meningitis. Untreated cryptococcal meningitis is fatal. Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt placement complicated by cryptococcal infection has rarely been reported.

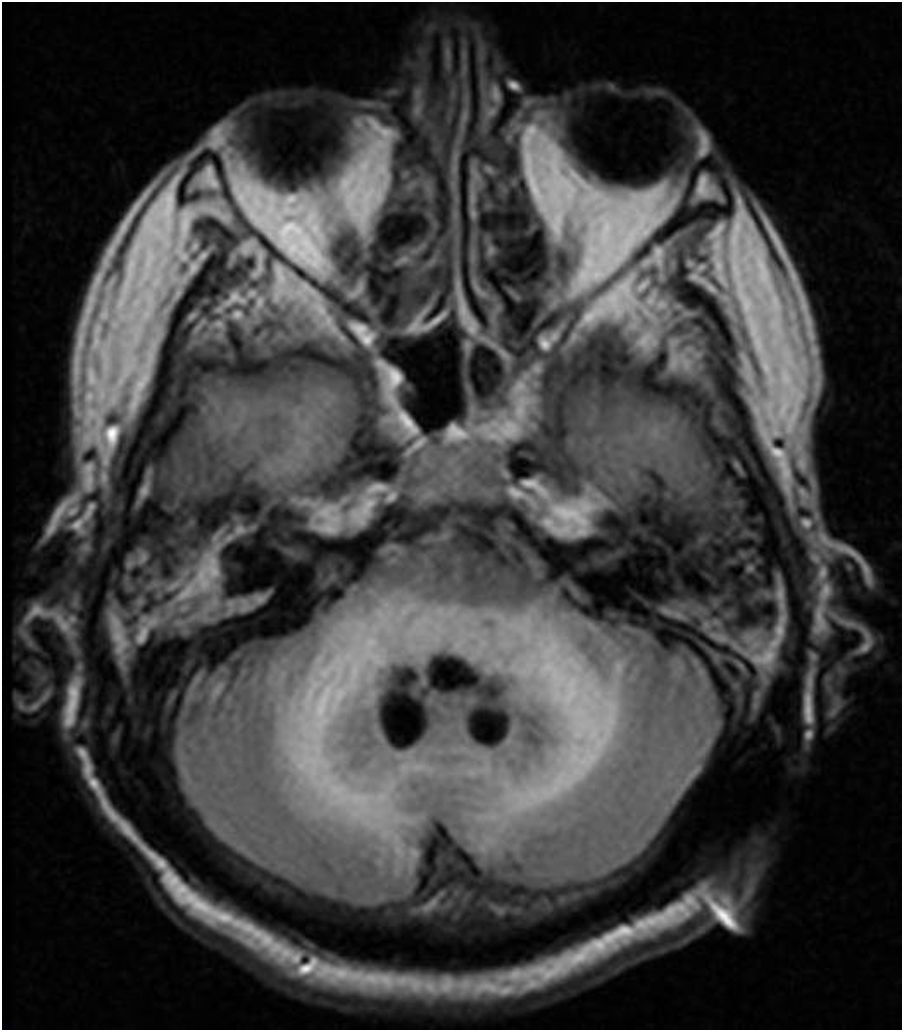

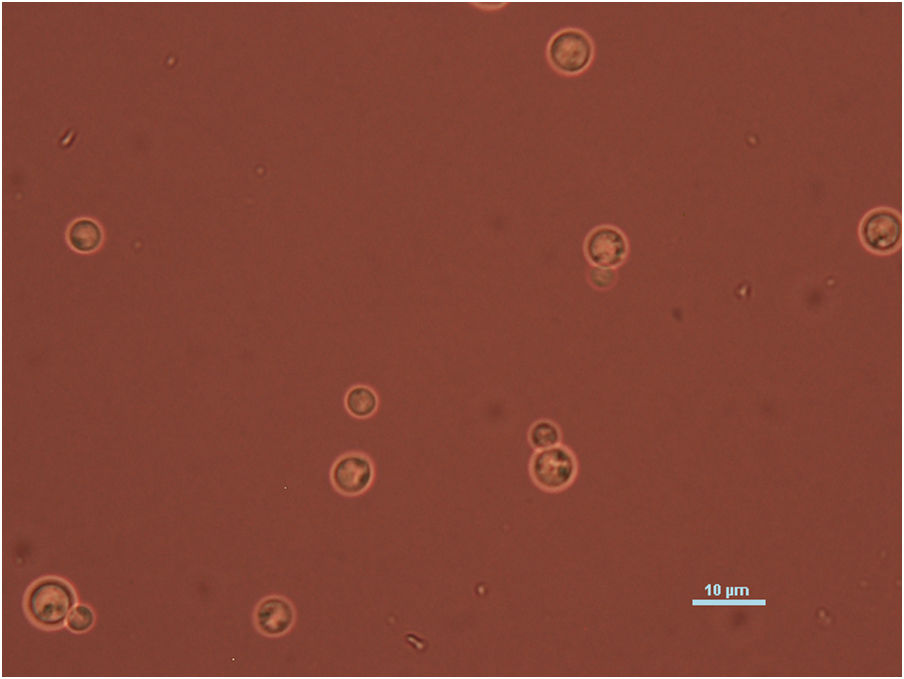

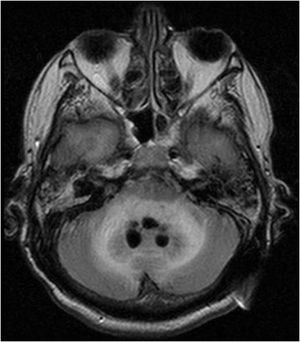

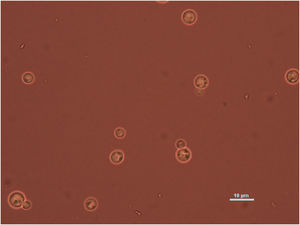

Case reportWe present the case of a 58-year-old man with diabetes, treated for two years due to chronic hydrocephalus, supposedly ensuing from tuberculous meningitis, with a VP shunt. He had a history of multiple VP shunt revisions with no improvement, and was referred to the Amrita Institute for further management. Computed tomography of the head showed the presence of the shunt in situ and a defect of the previous craniotomy (Fig. 1), dilatation of the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles, and periventricular hypointensities with no evidence of bleeding. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast of the brain showed gross hydrocephalus, ependymal enhancement along the occipital horn and the fourth ventricle (suggestive of ependymitis), and no evidence of focal enhancing lesions (Fig. 2). Hematological examination revealed microcytic hypochromic anemia and a leukocyte count of 17,900cells/μl (87% polymorphonuclear leukocytes). Cortisol concentration was 24μg/dl, C-reactive protein 250 mg/l, HbA1c 8.6%, fasting glucose concentration 170 mg/dl, hemoglobin 13.8g/dl, platelet count 372K/μl, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 34mm/h. The serological tests for HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C were negative. Liver, renal, and thyroid function tests were unremarkable. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed 5leucocytes/μl, glucose 98mg/dl, and protein 250mg/dl. The patient underwent a surgical procedure to insert a long-tunneled external ventricular drainage on the right side of the brain and to remove the previous shunt. Cultures of the CSF and the external ventricular drain tip showed the growth of Cryptococcus sp., based on its pigmentation on niger seed agar (Fig. 3) and the observation of encapsulated budding yeast cells under the microscope (Fig. 4). CSF smears for acid-fast bacilli and cultures of mycobacteria were negative. The blood cultures were negative. The two isolates recovered were identified as Cryptococcus neoformans with 95% probability using the automated VITEK 2 compact system using the YST card (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France). In order to ensure the identification, a molecular typing technique, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the URA5 gene, was performed to both the isolates from the CSF and the drainage tip,16 comparing the banding pattern obtained with those of reference isolates. The isolates showed the molecular type VNI (serotype A). Serotyping and mating types were analyzed by PCR of the STE20 and STE12 genes.16 The isolates showed only one band of approximately 588 bp, specific for STE20Aα, confirming that the isolates were C. neoformans sensu stricto, mating type MATα. Antifungal susceptibility was determined using the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M27-A3 recommendations.2 The isolate showed low minimum inhibitory concentrations, below epidemiological cut-off values, for voriconazole (0.06μg/ml), fluconazole (8μg/ml), isavuconazole (<0.015μg/ml), posaconazole (<0.03μg/ml), amphotericin B (<0.06μg/ml), and 5-fluorocytosine (1μg/ml).6,7 The patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate, but died of cardiopulmonary arrest on the fifteenth postoperative day.

The estimated incidence of cryptococcal meningitis cases in India and Southeast Asia is approximately 120,000 or 3% per year, with a mortality of 20%–50%.18 A recent study from India found that the prevalence of cryptococcal antigenemia in HIV-infected adults with CD4 counts below 100cells/mm3 was 8%.18 In non-HIV-infected and immunocompetent patients cryptococcosis is rarely suspected, and treatment is started only when the patient does not improve with antibacterial or antitubercular drugs. The study of CSF in the laboratory by means of fungal culture, India ink preparation, and latex agglutination test for cryptococcal antigen, is invaluable for making a correct diagnosis. The CrAg latex agglutination test has been reported as 100% sensitive and specific.

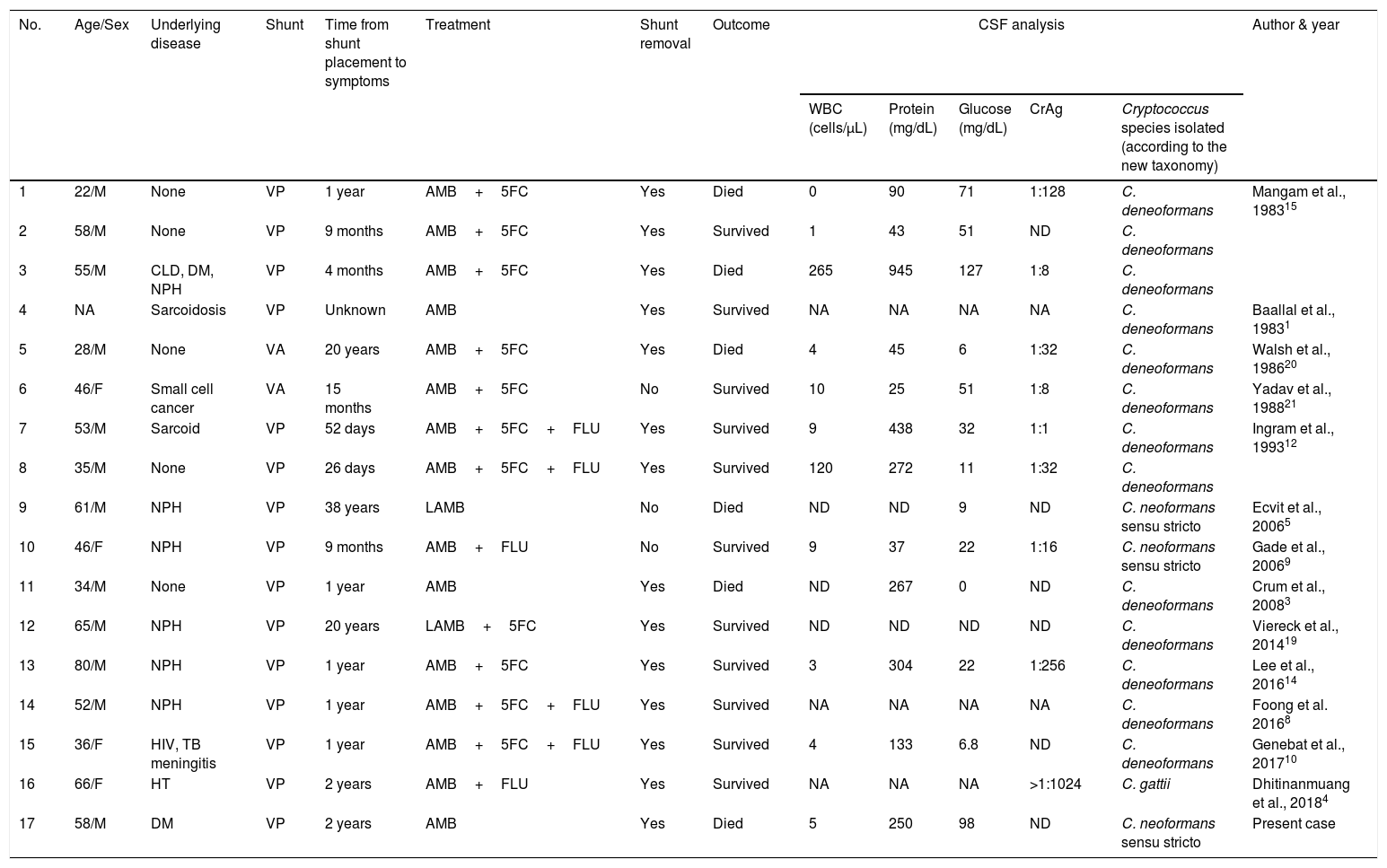

Concomitant tuberculosis with cryptococcal meningitis has been reported previously.18 Cryptococcal infections in VP shunts are unusual. Previous studies have described that VP shunts were placed in patients who presented with chronic hydrocephalus, which likely represented a complication of an underlying infection with C. neoformans.12 In the present case, the patient was wrongly diagnosed with tuberculous meningitis. The cryptococcal infection resulted in hydrocephalus before shunt placement. It was neither a de novo infection nor a complication of shunt placement. Among the 16 reported cases of cryptococcal VP shunt infection (Table 1), only in three cases the presence of C. neoformans was confirmed. The majority (88%) of the cases were diagnosed within two years of shunt placement. In three cases in which a cryptococcal infection was diagnosed after more than 20 years after having the shunt placed, the hydrocephalus and the cryptococcal infection may be independent events.5,19 In the other cases, underlying cryptococcal meningitis must have led to hydrocephalus, which was then relieved by the placement of the VP shunt. Thereafter, the silent cryptococcal infection may have led to a shunt infection. Cryptococcal VP shunt infection can also cause abdominal pseudocyst and subcutaneous pseudocyst.19 Both tuberculous and cryptococcal meningitis can lead to hydrocephalus, and VP shunting is a common therapeutic approach to relieve the increased pressure. Infection of the shunt is the most common complication and is caused mostly by bacteria and rarely by Cryptococcus species.

Clinical details of previously reported cases of cryptococcal shunt infections and the current case.

| No. | Age/Sex | Underlying disease | Shunt | Time from shunt placement to symptoms | Treatment | Shunt removal | Outcome | CSF analysis | Author & year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (cells/μL) | Protein (mg/dL) | Glucose (mg/dL) | CrAg | Cryptococcus species isolated (according to the new taxonomy) | |||||||||

| 1 | 22/M | None | VP | 1 year | AMB+5FC | Yes | Died | 0 | 90 | 71 | 1:128 | C. deneoformans | Mangam et al., 198315 |

| 2 | 58/M | None | VP | 9 months | AMB+5FC | Yes | Survived | 1 | 43 | 51 | ND | C. deneoformans | |

| 3 | 55/M | CLD, DM, NPH | VP | 4 months | AMB+5FC | Yes | Died | 265 | 945 | 127 | 1:8 | C. deneoformans | |

| 4 | NA | Sarcoidosis | VP | Unknown | AMB | Yes | Survived | NA | NA | NA | NA | C. deneoformans | Baallal et al., 19831 |

| 5 | 28/M | None | VA | 20 years | AMB+5FC | Yes | Died | 4 | 45 | 6 | 1:32 | C. deneoformans | Walsh et al., 198620 |

| 6 | 46/F | Small cell cancer | VA | 15 months | AMB+5FC | No | Survived | 10 | 25 | 51 | 1:8 | C. deneoformans | Yadav et al., 198821 |

| 7 | 53/M | Sarcoid | VP | 52 days | AMB+5FC+FLU | Yes | Survived | 9 | 438 | 32 | 1:1 | C. deneoformans | Ingram et al., 199312 |

| 8 | 35/M | None | VP | 26 days | AMB+5FC+FLU | Yes | Survived | 120 | 272 | 11 | 1:32 | C. deneoformans | |

| 9 | 61/M | NPH | VP | 38 years | LAMB | No | Died | ND | ND | 9 | ND | C. neoformans sensu stricto | Ecvit et al., 20065 |

| 10 | 46/F | NPH | VP | 9 months | AMB+FLU | No | Survived | 9 | 37 | 22 | 1:16 | C. neoformans sensu stricto | Gade et al., 20069 |

| 11 | 34/M | None | VP | 1 year | AMB | Yes | Died | ND | 267 | 0 | ND | C. deneoformans | Crum et al., 20083 |

| 12 | 65/M | NPH | VP | 20 years | LAMB+5FC | Yes | Survived | ND | ND | ND | ND | C. deneoformans | Viereck et al., 201419 |

| 13 | 80/M | NPH | VP | 1 year | AMB+5FC | Yes | Survived | 3 | 304 | 22 | 1:256 | C. deneoformans | Lee et al., 201614 |

| 14 | 52/M | NPH | VP | 1 year | AMB+5FC+FLU | Yes | Survived | NA | NA | NA | NA | C. deneoformans | Foong et al. 20168 |

| 15 | 36/F | HIV, TB meningitis | VP | 1 year | AMB+5FC+FLU | Yes | Survived | 4 | 133 | 6.8 | ND | C. deneoformans | Genebat et al., 201710 |

| 16 | 66/F | HT | VP | 2 years | AMB+FLU | Yes | Survived | NA | NA | NA | >1:1024 | C. gattii | Dhitinanmuang et al., 20184 |

| 17 | 58/M | DM | VP | 2 years | AMB | Yes | Died | 5 | 250 | 98 | ND | C. neoformans sensu stricto | Present case |

WBC: white blood cell; VP: ventriculoperitoneal; VA: ventriculoatrial; AMB: amphotericin B deoxycholate; CLD: chronic liver disease; CrAg: cryptococcal antigen; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; CT: computed tomography; DM: diabetes mellitus; 5FC: 5-fluorocytosine; F: female; FLU: fluconazole; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HT: hypertension; LAMB: liposomal amphotericin B; M: male; NPH: normal pressure hydrocephalus; TB tuberculosis; ND: not done; NA: not available.

C. neoformans sensu stricto and C. deneoformans mentioned in the table were reported as C. grubii and C. neoformans in the corresponding articles.

Underlying immunodeficient conditions such as HIV, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, chronic liver disease, and sarcoidosis were identified in six cases of cryptococcal VP shunt infection.13 The majority (83%) of the cases were treated with shunt removal followed by systemic antifungal therapy. Prior culture-proven tuberculous meningitis was documented in only one case,14 and mortality among these patients is as high as 35% despite treatment, which may be due to the advanced stage of the disease as a result of delayed diagnosis. Untreated cryptococcal meningitis is always fatal and needs to be differentiated from other causes of chronic meningitis, such as tuberculous meningitis, especially in countries where mycobacterial infections are endemic.20 Cryptococcal VP shunt infection is a complication of shunt placement in previously infected patients and is not caused by nosocomial transmission of Cryptococcus during placement. Cryptococcal antigen detection is a highly specific and rapid test that should be used with these patients in a previous screening. This report underlines the need to rule out cryptococcal infections in all cases of chronic meningitis with hydrocephalus.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.