A Chilean 35-year-old male patient with a history of primary infertility made an appointment at the Unit of Reproductive Medicine at Clínica Las Condes, Santiago, Chile. Multiple semen analyses revealed abnormal sperm morphology as the most prevalent finding. Multiflagellated and macrocephalic spermatozoa were observed and indicated a possible macrozoospermic phenotype. The constant presence of abnormal sperm morphology led the scope of the study to include Aurora Kinase C (AURKC) gene sequencing. The patient was diagnosed with a homozygous mutation of this gene. The mutation was detected in exon 6, type c.744C>G+/+ (P.Y248*) variant. As previously described in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD), this pathogenic variant is associated with macrozoospermia. Although this mutation is not the most frequently observed, it is the first of its kind reported in Latin America.

Un chileno de 35 años con antecedentes de infertilidad primaria consultó en la Unidad de Medicina Reproductiva de la Clínica Las Condes, Santiago, Chile. Múltiples espermiogramas revelaron una morfología anormal de los espermatozoides como la anomalía más relevante. Se observaban espermatozoides multiflagelados y macrocefálicos, lo que indicaba un fenotipo de macrozoospermia. La uniformidad del patrón observado condujo a ampliar el enfoque del estudio hacia la secuenciación del gen cinasa Aurora C (AURKC). Al paciente se le diagnosticó una mutación homocigota de este gen. La mutación fue detectada en el exón 6, con la variante c.744C>G+/+ (P.Y248*). Como se ha descrito anteriormente en la Base de Datos de Mutaciones de Genes Humanos (HGMD), esta variante patogénica se asocia a macrozoospermia. Aunque esta mutación no es la que se observa con más frecuencia, es la primera de su tipo notificada en Latinoamérica.

Fifteen percent of couples suffer fertility problems, with male and female factors contributing equally. The male factor is mainly assessed through semen analysis (spermiogram). Moderate sperm alterations are usually multifactorial in etiology, while severe alterations are predominantly due to genetic factors.1

Sex chromosome aneuploidies (e.g. Klinefelter and XYY syndrome) are the most prevalent genetic causes of primary spermatogenic deficiency, affecting 1:500 men.2 These are followed by Y-chromosome microdeletions, affecting 5–20% of azoospermic men.3 Spermatogenic deficiency also relates to structural chromosomal alterations (deletions, translocations, inversions) and single-gene mutations.4

Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has made changes to sperm morphology cut-off values. It originally defined >50% as normal, while the latest publication5 incorporated Kruger's strict criteria of >4% being normal. Teratozoospermia is defined as >90% of abnormal morphology. Polymorphic teratozoospermia demonstrates varied morphological defects within the heads and flagella of spermatozoa, and is usually linked to patient's lifestyle. Meanwhile, monomorphic teratozoospermia is strongly linked to genetic factors, displaying uniformly abnormal spermatozoa6; this condition includes globozoospermia, multiple morphological anomalies of the flagella, and macrozoospermia.7

Nistal et al.8 first characterized macrozoospermia with large-headed, multi-flagellate and polyploid spermatozoa. Other studies linked macrozoospermia to severe oligoastenozoospermia.9,10 Since Dieterich et al.11 identified the Aurora kinase C (AURKC) gene (chromosome 19q13.43) as the primary gene associated with macrozoospermia, several mutations have been reported.

The Aurora kinase A, B, and C proteins are cell cycle regulatory enzymes that ensure the accurate formation of the spindle apparatus for chromosomal segregation during cell division.12 In spermatogenesis, AURKC protein ensures the accurate segregation of chromosomes during meiosis and cytokinesis.13 Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies have shown that macrozoospermic patients have aneuploidy rates of approximately 100%.14 Therefore, lack of AURKC activity impairs meiotic division and yields to aneuploid macrocephalic spermatozoa, causing primary infertility.15

MethodsSpermiogramAll semen samples were collected and analysed according to the current WHO guidelines.5

Genetic studyThe genetic study was performed at Laboratorio Sistemas Genómicos, S.L., Valencia, Spain. Genomic DNA was extracted from blood and amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using primers for the 7 coding exons and adjacent introns of the AURKC. Purified PCR products were sequenced and compared against reference AURKC gene sequences (NM_001015878.1).

EthicsThe patient consented for his case to be reported. All his personal information was kept anonymously.

ResultsA Chilean 35-year-old male with history of chronic arterial hypertension and insulin resistance, consulted at the Unit of Reproductive Medicine (URM) of Clínica Las Condes after 3 years of primary infertility. He had no known history of orchitis, testicular torsion, cryptorchidism, sexually transmitted diseases, urinary tract infections or substance abuse. His partner completed various routine gynecological examinations, ruling out a female infertility factor.

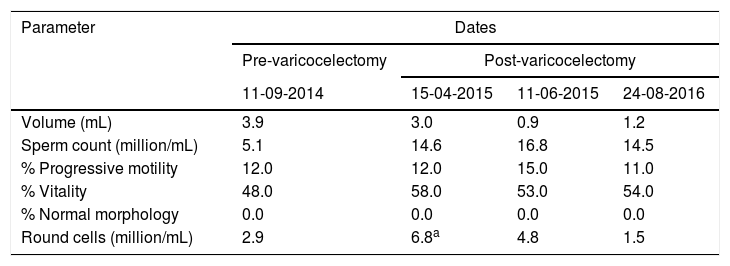

The patient had history of a grade II bilateral varicocele and a spermiogram that showed low sperm concentration (5.1million/mL), low motility (12% progressive) and 0% normal spermatozoa (Table 1).

Semen analysis results.

| Parameter | Dates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-varicocelectomy | Post-varicocelectomy | |||

| 11-09-2014 | 15-04-2015 | 11-06-2015 | 24-08-2016 | |

| Volume (mL) | 3.9 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Sperm count (million/mL) | 5.1 | 14.6 | 16.8 | 14.5 |

| % Progressive motility | 12.0 | 12.0 | 15.0 | 11.0 |

| % Vitality | 48.0 | 58.0 | 53.0 | 54.0 |

| % Normal morphology | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Round cells (million/mL) | 2.9 | 6.8a | 4.8 | 1.5 |

The presence of round cells led to test for seminal infection, finding Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in semen samples. The patient was treated accordingly. The patient had an initial DNA Fragmentation index level of 65% and was reduced to 30% after the course of antibiotic and anti-inflammatory medication.

A bilateral varicocelectomy was performed 1 year before consulting at the URM of Clínica Las Condes.

The physical examination revealed normal development of primary and secondary sex characteristics, symmetrical testicular volume (∼20mL each) and a normal epididymis and vas deferens.

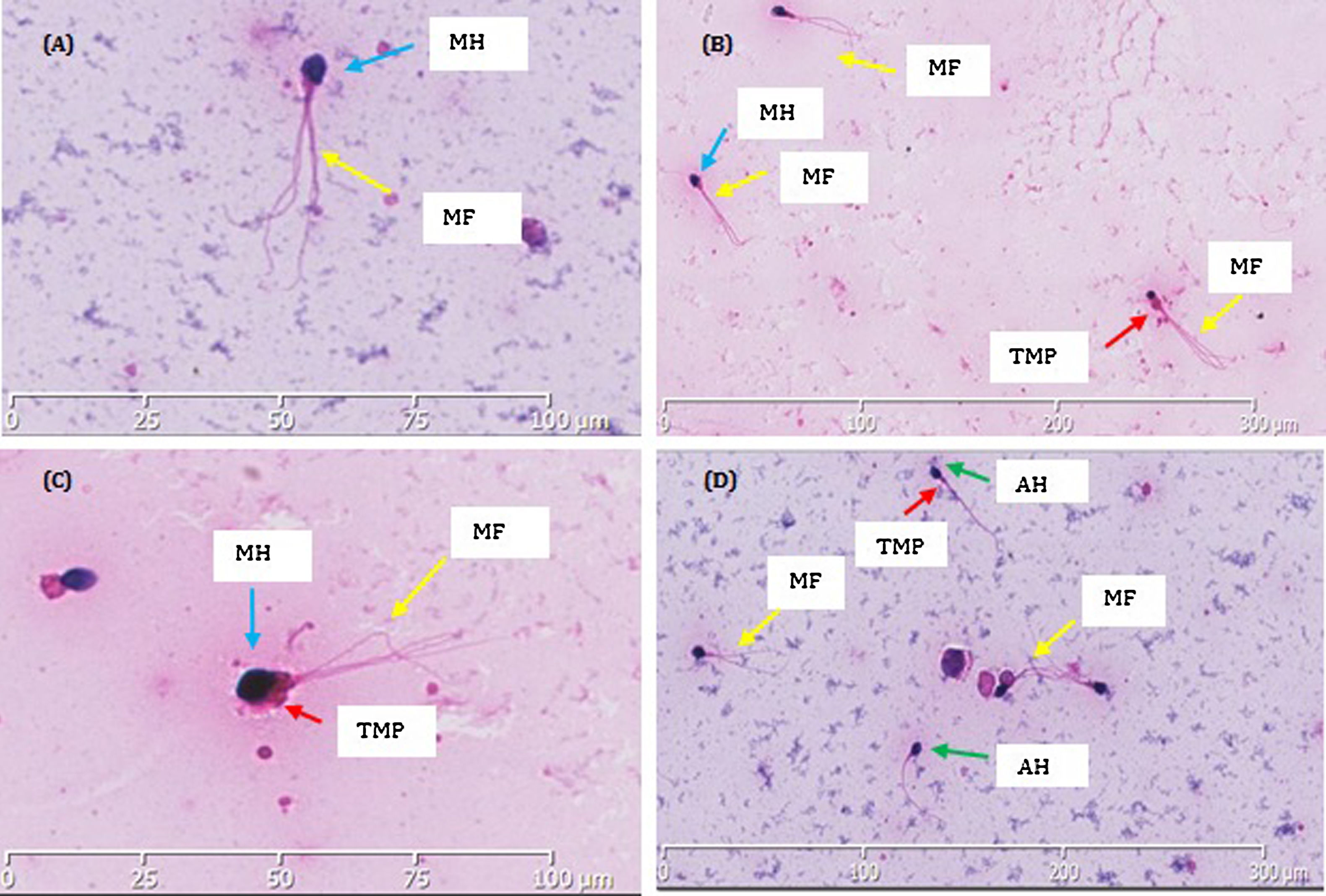

After varicocelectomy, sperm concentration rose from 5.1 to 14.6million/mL and remained around this value thereafter. However, motility showed no significant improvement and morphology consistently remained at 0% normal (Table 1). Interestingly, the morphology displayed a remarkable uniform pattern: larged-headed spermatozoa with multiple flagella (Fig. 1). A monomorphic teratozoospermia, particularly macrozoospermia, was suspected and the scope of the study was broadened to investigate for genetic anomalies.

Morphological (Hematoxylin/Eosin) staining showed the structure of the patient's spermatozoa. Macrocephalic and multiflagellated spermatozoa can be observed within images A–D. (A) A single spermozoa zoomed in, shows abnormal amorphous macrocephalic head (MH) and multiple flagella (MF). (B) All three spermatozoa show a uniform abnormality of large amorphous macrocephalic heads (MH) and multiple flagella (MF). (C) Two spermatozoa show consistent morphological abnormality. One spermatozoid has a macrocephalic head (MH), thick midpiece (TMP) and multiple flagella (MF). On the left there is a spermatozoid with a coiled tail. (D) Three spermatozoa have enlarged macrocephalic head (MH) with multiple flagella (MF). Two have amorphous oval heads (AH) and one with a thick midpiece (TMP).

Sequencing of the AURKC gene was of particular interest as discussed in the introduction. A homozygous c.744C>G (p.Tyr248) variant was found. This variant is a nonsense mutation located in exon 6, thus causing a premature stop codon to be substituted in place of a tyrosine amino acid. Therefore, this leads to the translation of a truncated and non-functioning protein of 248 rather than 309 amino acids.

DiscussionDieterich et al.11 were the first to link AURKC gene variants to macrozoospermia in North African men. They identified a homozygous mutation in exon 3 (c.144delC), resulting in a premature stop codon. A follow up study from the same group16 analyzed 62 infertile patients with teratozoospermia. From them, 32 had a uniform pattern of macrozoospermic spermatozoa. Genetic analysis revealed the same homozygous c.144delC variant in 31 of them.11 One patient had this variant in one allele, having a different variant in the other allele (p.C229Y). The remaining patients did not have macrozoospermia or AURKC gene mutations. The authors concluded that AURKC mutations could potentially be found in 1 in every 50 North African men.

Interestingly, Ben Khelifa et al.17 found the same c.144delC mutation in two brothers. Both siblings had a severe macrozoospermia affecting approximately 100% of spermatozoa. Sequencing of the remaining AURKC gene exons revealed a new mutation in both brothers: c.436-2A.G, located in exon 5. Later, the same group published a retrospective analysis15 that included 87 patients with teratazoospermia. Sixty-one patients had the homozygous mutation c.144delC and 10 patients had a nonsense mutation of P.Y248* (c744C>G) located in exon 6. They concluded that the c.144delC variant represents approximately 85.5% of mutated alleles, while the P.Y248* variant only the 13% and other mutations the 1.5%.

Eloualid et al.18 screened 326 infertile and 459 normozoospermic/fertile Moroccan males for AURKC gene variants. Among the infertile men, homozygous and heterozygous c.144delC mutation had frequencies of 1.23% and 1.84%, respectively. Among the control group, the homozygous mutation was not found, while 1.74% of them had the heterozygous mutation. Homozygous c.144delC patients had almost 100% macrocephalic spermatozoa. Heterozygous c.144delC patients did not exhibit any form of macrocephalic spermatozoa.

Ounis et al.19 studied 599 Algerian men for the presence of AURKC gene mutations. Fourteen patients had macrozoopermia. From them, 11 had AURKC mutations, with both c.144delC and PY248* variants being present. Therefore, 78.6% of the macrozoospermic men had AURKC mutations. Interestingly, the 3 macrozoospermic patients who did not carry the AURKC mutation also had altered morphology, but to a lower extent (70–75% abnormal spermatozoa) compared to the carriers of AURKC mutation (95–100% abnormal spermatozoa).

Ghédir et al.20 reinforced the link between macrozoospermia and the c.144delC variant by examining its frequency in Tunisian men and comparing results from the Maghrebian region. The study proposed that there is a greater frequency of macrozoospermia associated with c.144delC in homozygotic Tunisian men (0.5%) than in any other populations. This result may be explained by the high rate of consanguineous marriages that occur in Tunisia.

Our case study revealed that the patient was a homozygous carrier of the pathogenic c.744C>G (p. Tyr248) variant. Ben Khelifa et al.15 and also the HGMD mutation database (ID: CM071568)21 have previously described this variant as associated with macrozoospermia. This mutation has also been reported in the dbSNP database (ID: rs55658999)22 detailing that it has a frequency to occur in a population of <0.01%. The ExAc Browser Beta database23 describes that this mutation has a frequency in a control population of 0.043%. This variant has been identified to have harmful effects on protein translation and therefore in this case it was considered to be pathogenic. This variant has mainly been observed in various European studies. We consider our case to be the first of its kind reported in Latin America.

Carmignac et al.24 carried out an extensive review on diagnostic genetic testing for assisted reproductive technologies in patients with macrozoospermia. They concluded that systematic genetic screening of the AURKC gene could reasonably be performed for patients whose sperm contains 30% or more of large-headed spermatozoa. Although they found reports of spontaneous live births from macrocephalic spermatozoa, in none of those cases AURKC gene sequencing was completed nor AURKC gene mutations were found. Moreover, they were able to conclude that all patients with homozygous AURKC mutations failed at ICSI due to the high level of aneuploidy: they found no spermatozoa without aneuploidy, even for sperm that could be aspirated by the micropipette.

Based on the reported literature, we recommend that every teratozoospermic patient with predominant macrozoospermia should undergo molecular analysis to detect AURKC gene mutations. This will ensure that the patient is adequately informed regarding the possibility of his fertility. In the case of macrozoospermia linked to AURKC mutations, no form of assisted reproduction technique should be followed. Sperm donation or adoption can be recommended for these cases.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This case study was supported by the Unit of Reproductive Medicine of Clínica Las Condes. We want to thank Alejandra García, Susana Vargas, and Victor Castañeda, from “Centro de Espermiogramas Digitales Asistidos por Internet” (www.cedai.cl) for photographing the sperm morphology and DNA fragmentation images published in this paper. In addition, we want to thank them for providing visual assistance for the supplementary video within the links of this paper.