Nearly 50% of the college population struggles with academic procrastination, which is an impulsivity problem that often leads to emotional difficulties and college dropout. This study aimed to assess whether an online intervention on clarification of academic goals could reduce impulsivity and academic procrastination in college students. Forty-eight participants were assigned to three different types of interventions: (a) SMART-type goal clarification treatment (setting specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic and time-based goals); (b) instructional intervention for the abandonment of procrastination (conventional self-help type intervention); and (c) a waiting list. Only SMART intervention produced a statistically significant decrease in impulsivity (measured in terms of a hyperbolic discounting test; Whelan & McHugh, 2009), and academic procrastination (measured with the Procrastination Assessment Scale-Student – PASS), in both cases with small-to-moderate treatment effects. In conclusion, the study showed that online SMART-type goal clarification led to positive changes in impulsiveness and academic procrastination of college students, whereas a self-help protocol failed to produce similar effects. Potential reasons for reduced treatment effects of the SMART intervention are examined (e.g., experimental control). Also, prospective lines of research are discussed in view of the scarcity of experimental studies in this area.

Cerca del 50% de la población universitaria experimenta procrastinación académica, un problema asociado con impulsividad, dificultades emocionales y deserción. El estudio evaluó si una intervención en línea en clarificación de metas académicas reduce la impulsividad y la procrastinación académica de estudiantes universitarios. Cuarenta y ocho estudiantes fueron distribuidos en tres tipos de intervención: (a) clarificación de metas tipo SMART (establecer metas específicas, acordadas en colaboración, medibles, realistas, y basadas en criterios temporales); (b) seguimiento de instrucciones para abandonar la procrastinación (protocolo convencional de tipo autoayuda), y (c) lista de espera. La intervención SMART fue la única que produjo una disminución estadísticamente significativa en impulsividad —medida en términos de descuento hiperbólico (Whelan & McHugh, 2009)— y procrastinación académica —medida a través del Procrastination Assessment Scale-Student (PASS)—, en ambos casos con efectos de tratamiento de pequeños a moderados. En conclusión, el estudio demostró la efectividad de un protocolo en línea de clarificación de metas tipo SMART para reducir la impulsividad y la procrastinación académica de estudiantes universitarios, efectos que no fueron encontrados con la implementación de un protocolo de tipo autoayuda. Se discuten posibles razones por las cuales los efectos del tratamiento SMART no fueron mayores (e.g., control experimental), y líneas potenciales de investigación a futuro, esto especialmente considerando los escasos estudios experimentales en esta área.

Procrastination has been defined as postponing something unpleasant or difficult to do, and to end up doing it in a way that involves greater effort (Ainslie, 2008). As Ainslie (2008) states: It generally means to put off something burdensome or unpleasant, and to do so in a way that leaves you worse off. By procrastinating you choose a course that you would avoid if you choose from a different vantage point, either from some time in advance or in retrospect. Thus, the urge to procrastinate meets the basic definition of an impulse—temporary preference for a smaller, sooner (SS) reward over a larger, later (LL) reward. (p. 2).

Thus, procrastination is regarded as the tendency to make impulsive decisions to defer the personal costs when an activity is postponed, in order to give temporary preference to an immediate consequence at the expense of a delayed reward (Ainslie, 1975, 2010).

Problems associated with procrastinationProcrastination is a psychological phenomenon that extends broadly in society. Ferrari, O’Callahan, and Newbegin (2005) reported that 61% of the population display some form of procrastination, of which 20% do so in a chronic manner (e.g., routinely late for deadlines and postponing important tasks daily or weekly). However, procrastination has a particularly negative effect in academic contexts, where it occurs with high prevalence and chronicity. For instance, Steel (2007) reported that 80% of North American college students procrastinate – of which 50% do so in a chronic manner – and similar rates have been observed in Latin American populations (e.g., Peru – Carranza & Ramírez, 2013; Argentina – Furlan, Ferrero, & Gallart, 2014). Procrastinating behaviors are related to important problems of academic performance and the use of psychoactive substances. Students who procrastinate on their academic tasks often exhibit more problems related to physical symptoms of disease and stress, and this generates the need to visit health units more often (Glick, Millstein, & Orsillo, 2014; Tice & Bauneister, 1997).

Finally, there is a noteworthy number of studies that have reported associations between impulsive behavior of the type involved in chronic procrastination and poor school performance, drug use, and emotional problems (Abraham, Bond, & Richardson, 2012; Ainslie, 2010; Ahn et al., 2011; Cerda & Saiz, 2015; Clariana, 2013; Gaeta, Cavazos, Sánchez, Rosario, & Hogemann, 2015; Glick et al., 2014; Goetz, 2014; González-Brignardello & Sánchez-Elvira-Paniagua, 2013; Furlan et al., 2014; Hayes, Levin, Pistorello, & Seeley, 2013; McKerchar et al., 2009; Perrin et al., 2011; Riveros, Rubio, Candelario, & Mangin, 2013; Yesilkalayi, 2014; Zuluaga, 2010).

Procrastination, goals, and instructionsResearch on academic procrastination has established relations between following instructions and motivation for learning (Schunk, 2005). In particular, it has been found that students who demonstrate more skill in following their own instructions tend to be more academically motivated (Pintrich & Shunck, 1993). Monitoring self-instructions has been shown to be guided by the establishment of goals (Karas, Marcantonio, & Spada, 2009), and the instructional effect of clarifying goals has been facilitated by feedback on task development progress (Ramnero & Torneke, 2014). In addition, Howell and Watson (2007) found that the tendency to diverge from common learning strategies correlates with academic procrastination.

Hyperbolic discounting (HD) as a mechanism of procrastinationFrom Ainslie's (2010) theoretical approach, procrastination is a tendency to make impulsive decisions in the context of deciding to postpone costly or aversive tasks, or choosing not to wait for delayed consequences. Accordingly, procrastination may become a serious issue for an individual when it leads to constant impulsive decisions associated with the use of alcohol and other substances, as well as the postponement of significant pending tasks (Ainslie, 1975).

Within this theoretical context, Odum (2011) defines hyperbolic discounting (HD) as a tendency to choose more immediate alternatives – impulsive decisions – against deferred, greater alternatives – e.g., when faced with a choice test, an individual chooses $2000 here and now, instead of a delayed but greater consequence, such as receiving $10000 next weekend. From this approach, impulsivity, and thus procrastination, is explained by a permanent tendency to perceive the value as a hyperbolic discounting function (Ainslie, 1975), which entails a loss of value of delayed consequences over time. Story, Vlaev, Seymour, Darzi, and Dolan (2014) reviewed several studies and concluded that high discount rates (e.g., for money, food or drug rewards) are associated with several unhealthy behaviors and markers of health status, which establishes HD as an effective predictive measure of those maladaptive behaviors, including impulsivity across different domains. These findings supported the decision to implement Whelan and McHugh's (2009) HD test in the present study, as a measure of impulsivity.

Previous commitments and procrastinationPrevious commitments seem to change the way organisms accept delays of unpleasant events, or events which require effort (Ainslie, 1975, 2010). In the case of humans, Ainslie (2008) suggests that such commitments, understood as environmental controls, can be carried out through arrangements in task completion dates, or specifying targets for action divided into subsequent actions.

To Ainslie (2008), prior commitments of humans require the following:

- 1.

Establishing controls, such as task completion dates or completion sub goals; solving problems such as availability of rewards, unwanted costs, potential restrictions and demands of others.

- 2.

Avoiding alternative options, defining a schedule, and avoiding personal barriers and distractors.

There is evidence supporting the effectiveness of establishing prior commitments to reduce academic procrastination (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Kirby & Guastello, 2001). A study carried out by Kirby and Guastello (2001) found that students who make decisions on a weekly basis in relation to their academic performance appear more apt to choose valuable delayed rewards. Participants in this study were informed that such rewards were still scheduled and it was shown to them that their ability to choose them was ongoing. According to Ainslie (2010), the effect of these interventions depends on the fact that individuals can predict the extent of a delayed reward, highlighting its value as it becomes probable when perceived as achievable.

This approach regards procrastination as the tendency to make impulsive decisions, and from this stance it recommends making constant choices of actions, on a step-by-step basis. Accordingly, academic procrastination can be decreased if the individual's perception changes in terms of discounting the value of the task on account of delays or difficulties related to it.

Interventions in academic procrastinationA study carried out by Ariely and Wertenbroch (2002) with college students conducted an intervention in academic procrastination. This intervention consisted of a verification of the effect of prior commitments in meeting deadlines of task completion. The authors found that participants with a tendency to postponing the deadline for their tasks procrastinated less (e.g. in delivering a final paper) when they had defined the completion date themselves, in advance, within ample time. In addition, it was reported that the largest tendency to academic procrastination occurred in cases in which the deadline was not defined in advance, but deferred to the end, i.e., cases wherein there was no prior commitment.

Karas et al. (2009) demonstrated the effectiveness of a treatment to reduce academic procrastination, which focused on teaching specific skills for clarification of goals by way of coaching (15-min weekly meetings where goals, possible obstacles, personal resources and deadlines were defined). Training in academic goal clarification was conducted in six face to face sessions, where participants were guided through the coaching method to define specific academic procrastination reduction targets, thus seeking to solve problems related to postponement of tasks and confronting obstacles, in relation to their own beliefs and their own behavior. Intervention was focused on clarifying goals, establishing personal commitments, monitoring progress, managing time and preventing relapses.

Along the lines of the study conducted by Karas et al. (2009), Morisano, Hirsh, Peterson, Pihl, and Shore (2010) applied a SMART goal clarification process (the acronym stands for setting specific, measurable, agreed upon, realistic and time-based goals) with students who reported problems adjusting to academic demands. However – unlike the studies above – the authors carried out a treatment with experimental control conditions where they differentiated between a group which received treatment and one which did not. The treatment consisted of a single 2.5-h session during which participants performed clarification of their own academic goals by means of an online tool. Meanwhile, participants in the untreated group received an assessment of their vocational interests.

One limitation of the intervention carried out by Morisano et al. (2010) was its duration, namely a single 2.5-h session. Since academic procrastination is explained by a tendency in decision making, it seems feasible that academic goal clarification interventions could eventually have greater impact when implemented online: this approach would allow for more regular and frequent efforts, and would provide a broader period of time to form prior commitments and clarify goals in further detail. Research with the SMART goal clarification method (McLeod, 2012; Rubin, 2002) supports this interpretation.

SMART goal clarificationThe SMART method has been used for various purposes, such as rehabilitation of patients with addictions (Bovend’Eerdt, Botell, & Wade, 2010), effective teaching in school environments (O’Neil, 2006), and business leadership (Bowles, Cunningham, De la Rosa, & Picano, 2007).

This intervention method is based on the following principles: (a) defining goals, sub goals and academic objectives; (b) definition of time-related and personal deadlines to achieve goals; (c) personal establishment of goals; and (d) the use of customized and online strategies. However – unlike other academic goal clarification approaches – the SMART method is carried out in six steps where the individual writes, evaluates and retests commitments previously made during a month. In this sense, the method is more thorough and requires greater commitment.

Clarification of academic goals has proven effective in the management of academic procrastination in several studies (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Karas et al., 2009; Morisano et al., 2010; Rakes & Dunn, 2010). However, a review of the literature shows great heterogeneity in the way the procedures involved in this type of interventions are carried out: traditional classroom applications (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Karas et al., 2009) versus administration online and with new technologies (Morisano et al., 2010; Rakes & Dunn, 2010); and case analysis (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Karas et al., 2009) versus group comparisons and conditions of intervention (Morisano et al., 2010). Consequently, there arises the question as to whether online programming for goal clarification instructions – whether they be SMART or not – can generate decreases in academic procrastination and impulsiveness in comparison to the findings of other studies that have shown the effects of monitoring goals in these measurements of academic procrastination.

Overview of the studyThe present study aimed to verify whether online implementation of a SMART-type clarification of academic goals would result in a significant reduction of college students’ procrastination – measured with the Procrastination Assessment Scale-Student (PASS; Solomon & Rothblum, 1984) – and impulsiveness – measured with a HD test (Whelan & McHugh, 2009). While doing so, we aimed to overcome the methodological limitations of previous studies, such as Morisano et al. (2010), which focused on measuring the effects of clarifying academic goals only in terms of grade point averages, or the study conducted by Ariely and Wertenbroch (2002), which measured the effects of a treatment on the postponement of a single academic task. In addition, we aimed to compare the effects of such intervention based on clarification of academic goals versus one solely based on providing a set of instructions for leaving procrastination, i.e., a conventional self-help intervention.

MethodParticipantsForty-eight college students (second-year psychology majors taking three different courses) aged 18–22 years (M=19.35, SD=1.04) – 39 women and 9 men – participated in this study (all domiciled in the city of Tunja, Colombia). All the participants volunteered to take part in the study and signed an informed consent before being formally enrolled in the study. Distribution of the participants in the three groups for the study was conducted using random quota sampling (see the Design section). All procedures complied with national and international ethical guidelines for psychological research (American Psychological Association – APA, 2002; Colombian Board of Psychologists, 2006).

InstrumentsSMART clarification of academic goals. Below is the detailed description of each of the steps for implementing SMART goals, in accordance with McLeod (2012) − an online version can be found in http://establecimientodemetasinteligentes.blogspot.com.co or may be obtained upon request. This intervention was implemented in the present study via Google Docs© platform. Students and researcher – first author – exchanged WORD and EXCEL files in which each one of the steps was implemented and feedback was provided through a record of their performance on the steps established, or when needed:

- •

Step 1. The participants were asked to write about the potential impact of achieving a goal in their lives and those of others. Participants should have established achievements or ends which are desirable for themselves. This aimed to help participants obtain a more detailed understanding of the importance of goals and consequences of their achievement. In an effort to make this step more objective, students wrote in detail the specific goals they wished to achieve, the actions that could have led to the attainment of these goals, and the limitations they could have faced in the process. Similarly, students defined what they commit to do from the beginning in order to carry out these actions and overcome potential barriers.

- •

Step 2. Students received help from the tutor (researcher) to develop more specific plans for achieving their goals. Participants were asked to describe each step for attaining each goal or objective.

- •

Step 3. Sub-targets were determined in collaboration with the tutor (researcher), as well as the specific steps to attain them.

- •

Step 4. The student was asked to identify potential obstacles that may have arisen when attempting to reach the previously defined, and the strategies to be implemented to prevent the abovementioned obstacles.

- •

Step 5. Tutor or advisor helped the participant to establish guidelines that could have allowed him/her to perform feedback on implementation and achievement of sub-goals and goals.

- •

Step 6. The participants were asked to evaluate the level of commitment with the achievement of their goals, and seek help from another person to accomplish their goals.

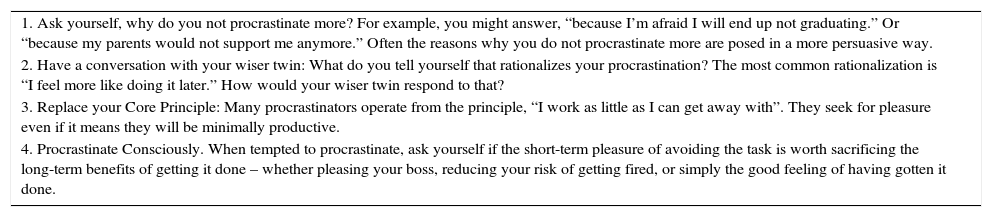

Instructions for abandoning procrastination. According to Nemko (2015, April 12), following 11 steps or instructions, which can be delivered impersonally, is likely to have an impact on reducing procrastination regarding the fulfillment of important tasks. Such advice or guidance is exemplified in Table 1.

Instructions to abandon procrastination in fulfilling tasks.

| 1. Ask yourself, why do you not procrastinate more? For example, you might answer, “because I’m afraid I will end up not graduating.” Or “because my parents would not support me anymore.” Often the reasons why you do not procrastinate more are posed in a more persuasive way. |

| 2. Have a conversation with your wiser twin: What do you tell yourself that rationalizes your procrastination? The most common rationalization is “I feel more like doing it later.” How would your wiser twin respond to that? |

| 3. Replace your Core Principle: Many procrastinators operate from the principle, “I work as little as I can get away with”. They seek for pleasure even if it means they will be minimally productive. |

| 4. Procrastinate Consciously. When tempted to procrastinate, ask yourself if the short-term pleasure of avoiding the task is worth sacrificing the long-term benefits of getting it done – whether pleasing your boss, reducing your risk of getting fired, or simply the good feeling of having gotten it done. |

Participants’ level of academic procrastination was measured using the Procrastination Assessment Scale-Student (PASS; Solomon & Rothblum, 1984). Recent studies have reported acceptable evidence of structural validity (via confirmatory factor analysis; Yockey & Kralowec, 2015) and reliability (e.g., between .74 and .85; Alexander & Onwuegbuzie, 2007; Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2001; Yockey & Kralowec, 2015) for this scale. In the present study, a translated and adapted version of the PASS for Colombian population was implemented (on going psychometric analyses; Sánchez, Quant, & Molina, 2015). Only scores related to the frequency of procrastination were analyzed in the present study.

Each participant filled out the questionnaire online. Items were related to incidence and relevance of procrastination across different areas. For instance, participants were asked “to what degree do you procrastinate on writing a term paper?” to which they could answer using a scale that ranged from never procrastinate to always procrastinate. A total score in academic procrastination (TAP) was obtained for each participant by assigning a numerical value to the 5-point Likert for each question (Sánchez et al., 2015; Solomon & Rothblum, 1984).

Hyperbolic discounting (HD)The hyperbolic discounting (HD) test used in this study was based on the task that Whelan and McHugh (2009) developed in order to measure impulsive tendencies when deciding to opt for hypothetic amounts of money. Participants accessed a web page in which 103 trials were presented. During each of these trials, the participant chose among two hypothetical options: a given amount of money available immediately but of small value, versus a delayed sum of money of greater value. Across the trials, the specific values of the delays and amounts of money varied randomly, but the proportion between those values remained constant. For instance, in one trial the participant could choose between $5000 pesos (1.5 USD approximately) available immediately and $10000 pesos available tomorrow, in the next trial between $120000 available now and $140000 available in five days, and in a third trial between $5000 available now and $10000 available in five days. Based on Reed, Kaplan, and Brewer (2010), the software automatically calculated the participant's preference across trials for delayed or immediate options, and provided a single measure of hyperbolic temporal discount (HD). Such measure ranged between 0 and 1, with values approaching 0 indicating high impulsivity in situations of decision making and values approaching .5 low impulsivity in situations of decision making (Whelan & McHugh, 2009). A copy of the HD test is available on http://olanod.github.io/temporal-discounting and the steps and EXCEL macro for calculating the HD measure are available upon request.

DesignA group-comparison design with two types of treatment and a control group with measures for pretest, posttest, academic procrastination (TAP) and impulsiveness in HD was implemented (Kazdin, 1992).

ProcedureAll procedures described below were implemented by the first author, with close supervision of the second author (graduate advisor). Fifty students were informed they could be part of the study in a first contact via e-mail and during classes (August, 2015). At that time, they received an overview of the research, as well as its purpose, which was testing treatments to improve academic procrastination, and its potential benefits at a clinical and personal level. From the 50 potential participants, 48 agreed to participate in the study by signing an informed consent form.

During the first three weeks of the study, participants filled out online questionnaires corresponding to the pretest measures (HD and TAP). By the end of the third week, students were separated into two treatment groups (A and B) and a waiting list group (C) using a random quota selection (Catch Up, Kazdin, 1992). As a result, each group consisted of 16 participants. Online treatment started for groups A and B (group C began its period on the waiting list) after the selection of the three groups was completed.

Participants in group A received virtual (online) treatment in SMART academic goal clarification for a month. The treatment consisted in fulfilling six steps − approximately two steps weekly (online version available at http://establecimientodemetasinteligentes.blogspot.com.co/or may be obtained upon request). Students and tutor – first author – exchanged WORD and EXCEL files in which each one of the steps was implemented and feedback was provided through a record of their performance on the steps established, or when needed (see detailed description of each step on section Instruments). First, they defined the possible impact of the goals they wanted to achieve; secondly, they defined specific steps to achieve their goals; thirdly, they defined the subgoals necessary to achieve their goals; fourth, they identified possible obstacles to their goals; fifth, they defined guide points to obtain feedback on their own personal progress; and lastly, they assessed their commitments and asked for close people's help.

The goal-clarification procedure followed behavioral principles, which specify contexts, background and consequences of planned actions. For example, a participant stated that “he wanted to comply more with his study schedules.” Then, he defined specific steps, including “working out a schedule, and checking daily how it was met”. This led the participant to highlight the need to frequently checking his schedule and its compliance, finding obstacles such as “neglecting, losing interest or feeling burdened with many obligations.” Finally, the participant made a commitment with “one of his classmates,” in order to show her that he was complying with the established schedule.

Meanwhile, participants assigned to group B received 11 instructions to abandon procrastination (see Instruments section) based on recommendations made by Nemko (2015), with two weekly email deliveries during the month of treatment. Different to group A, no further interaction occurred between the tutor (researcher) and the participants. Finally, participants in group C began to receive e-mails with the 11 instructions to abandon procrastination one month after having started the study, i.e., the same treatment of group B.

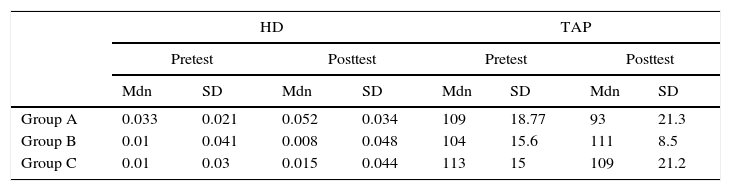

ResultsAn initial exploratory data analysis of HD and TAP measures indicated non-parametric distributions and considerable within-group variability across groups. Based on these outcomes, it was decided to conduct statistical data analyses in accordance with such characteristics of the data, namely Mann–Whitney (U) and Wilcoxon sign ranked (V) non-parametric tests (Kühnast & Neuhäuser, 2008). Descriptive pretest and posttest measures of HD and TAP are shown in Table 2.

Descriptive pretest and posttest measures in hyperbolic discounting (HD) and total academic procrastination (TAP).

| HD | TAP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | |||||

| Mdn | SD | Mdn | SD | Mdn | SD | Mdn | SD | |

| Group A | 0.033 | 0.021 | 0.052 | 0.034 | 109 | 18.77 | 93 | 21.3 |

| Group B | 0.01 | 0.041 | 0.008 | 0.048 | 104 | 15.6 | 111 | 8.5 |

| Group C | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.044 | 113 | 15 | 109 | 21.2 |

Note: Group A = SMART academic goal clarification; Group B = instructions to abandon procrastination; Group C = waiting list. Mdn=median; SD=standard deviation.

Similar HD entry levels of the three groups were confirmed, as no significant differences were found between pretest measures. Though HD post-test scores of group A were higher from those of group B and C (i.e., less impulsivity), a statistically significant difference (U=62, z=−2.301, p=.021) was only found between group A (Mdn=.052) and group B (Mdn=.008), with a clear tendency to an increase in posttest HD values of group A. An effect-size analysis (Delta; McBeth, Razumiejczyk, & Ledesma, 2011) of this difference resulted in a Delta=.3, p≤.05, which could be considered a small-medium effect. Note that Cliff's calculator for Delta does not report specific confidence intervals (see McBeth et al., 2011).

A statistically significant difference between pretest (Mdn=.033) and posttest (Mdn=.052) HD scores was only found in group A (V=108, z=−2068, p=.039). The fact that the change in those scores was in terms of an increase, indicates a decrement in impulsiveness in decisions by participants after the SMART goal clarification treatment. An effect-size analysis of this variation in HD scores resulted in a Delta=−.3, p≤.05 (small-medium effect).

Total academic procrastination (TAP)Similar TAP entry levels of the three groups were confirmed, as no significant differences were found between pretest measures. An analysis of posttest TAP measures across the three groups, resulted in a single statistically significant difference (U=172, z=2.06, p<.041) between group A (Mdn=93) and group C (Mdn=109), with an effect size Delta=−.4, p≤.05. Such difference in TAP scores indicates an overall lower tendency to academic procrastination in the group exposed to SMART goal clarification treatment (group A), when compared to control group (group C; waiting list). Lastly, post-test TAP scores of group A and C declined when compared to pre-test scores, whereas they slightly increased in group C; however, these differences were not statistically significant.

DiscussionThis study aimed to test the effects of two treatment conditions – SMART academic goals clarification and instructions to abandon procrastination – and one control condition (waiting list) on measures of impulsiveness in academic procrastination, namely hyperbolic discounting (HD) and total academic procrastination (TAP) score of the PASS questionnaire. The results indicate that (a) the participants who received the academic goal clarification intervention had significant changes on HD posttest measures than did participants who received instructions to abandon procrastination; and (b) the participants who received the goal clarification treatment presented a significant reduction in academic procrastination when compared to subjects who were in the control condition (i.e., waiting list). These outcomes support the main hypothesis of the study: the group of students exposed to the SMART-type academic goal clarification had a substantial decrease in their tendency to academic procrastination and impulsiveness when faced with hyperbolic-discounting decisions.

The two aforementioned findings are consistent with those obtained in previous research regarding how goal clarification leads to a decrease in measures of academic procrastination (Karas et al., 2009; Morisano et al., 2010). More importantly, supporting evidence of the effect of goal clarification was attained while overcoming some of the limitations of previous studies. For instance, though Morisano et al. (2010) showed a significant change in pretest and posttest measures related to procrastination as a result of implementing an academic goal clarification treatment, their study was limited by the fact that their design did not entail comparisons with a condition in which there was an absence of treatment. Furthermore, the outcomes of the present study support the existence of a relationship between following one's own instructions and the tendency to complete academic tasks in a timely fashion, which has also been demonstrated in previous studies (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Howell & Watson, 2007; Karas et al., 2009; Pintrich & Shunck, 1993).

Unlike previous research (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Karas et al., 2009; Morisano et al., 2010), this study implemented a SMART-type academic goal clarification method that entailed a longer period of duration (one month). Consideration of this fact suggests that changes in academic procrastination could be related not only to the approach of the intervention (SMART), but also to its duration. It seems plausible that treatments with durations equal to or longer than several weeks are more likely to be effective on producing reliable changes on procrastination. Evidently, there is a need for research that manipulate the variables of duration and intensity of treatments that entail goal clarification, so as to ascertain both the potential positive and negative effects of providing long-term interventions on academic procrastination.

Although one strength of the study, when compared to previous research, lies in the fact that the design implemented facilitated a comparison between the presence and absence of treatment and pretest and posttest measurements, the observed effects might be considered small to moderate by the standards that have been proposed in this regard (e.g., Cohen, 1998). In addition, the small number of participants per group, the lack of control over the procrastination entry level of the participants (e.g., clinical versus nonclinical samples), the fact that pre-post TAP differences in the SMART group were not significant, and the use of certain statistical analyses due to the inherent characteristics of the data (e.g., distribution) limit the scope of the study. Notwithstanding these limitations, which evidently further research should address, this study contributes to a field wherein it has been reiterated that online interventions of academic procrastination promise many uses but more experimental research is still needed (Davis & Abbit, 2013; Morisano et al., 2010; Pintrich & Shunck, 1993; Schunk, 2005). This is particularly the case because many treatment implementations have only been exploratory so far, thus they need to be tested in increasingly appropriate conditions in order to refine and validate treatments with greater impact.

Overall, the relevance of the present study lies in its demonstration that an online SMART-type academic goal clarification method can have effects on measures of impulsiveness and academic procrastination; this in particular if considering that impulsiveness and academic procrastination are strongly associated with behavioral problems (e.g. addictions and dropout rates; Abraham et al., 2012; Ahn et al., 2011; Bickel, Odum, & Maden, 1999; McKerchar et al., 2009; Odum, 2011; Steel, 2007; Zuluaga, 2010) and emotional difficulties in college populations (e.g. anxiety, depression, anguish and stress; Abraham et al., 2012; Critchfield & Kollins, 2001; Ferrari et al., 2005; Howell & Watson, 2007; Sánchez, Quant, & Molina, 2015). Further research could extend these promising findings by (a) identifying the role of feedback on its own and/or just interacting with a tutor, (b) exploring differential effects that goal-clarification intervention may have on specific areas and reasons of procrastination (e.g., using additional information provided by the same instrument – PASS); and (b) testing whether face-to-face SMART-type goal clarification leads to lesser, similar, or superior effects than the online implementation carried out in this study, not only analyzing measures of procrastination and impulsivity, but also examining potential effects on other relevant variables (e.g., course grades or grade point average – GPA).

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to express our gratitude to Professors Yors García and Juan Carlos Rincón for their input during different stages of this project.

This study was conducted with the support of Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja and as the first author's graduation requirement to obtain the Master's Degree in Clinical Psychology at Fundación Universitaria Konrad Lorenz.