The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ) is a recently published measure of cognitive fusion – a key construct in the model of psychopathology of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). This study presents the psychometric properties and factor structure data of a Spanish translation of the CFQ in Colombia. Three samples with a total of 1,763 participants were analyzed. The Spanish CFQ showed psychometric properties very similar to the ones obtained in the original version. Internal consistency across the different samples was good (Cronbach's alpha between .89 and .93). The one-factor model found in the original scale showed a good fit to the data. Measurement invariance was also found across sample and gender. The mean score of the clinical sample on the CFQ was significantly higher than the scores of the nonclinical samples. CFQ scores were significantly related to experiential avoidance, emotional symptoms, mindfulness, and life satisfaction. The CFQ was sensitive to the effects of a 1-session ACT intervention. This Spanish version of the CFQ shows good psychometric properties in Colombia.

El Cuestionario de Fusión Cognitiva (CFQ) es una medida de fusión cognitiva recientemente publicada; un constructo clave en el modelo de psicopatología de la terapia de aceptación y compromiso. El presente estudio muestra las propiedades psicométricas y estructura factorial de una traducción al español del CFQ en Colombia. Se analizaron tres muestras con un total de 1763 participantes. La versión en español del CFQ mostró resultados muy similares a los obtenidos en la versión original. La consistencia interna a través de las distintas muestras fue buena (alfa de Cronbach entre .89 y .93). El modelo unifactorial encontrado en la escala original mostró un buen ajuste a los datos. Se encontró invarianza de la medida a través de muestras y sexo. La puntuación media de la muestra clínica en el CFQ fue significativamente mayor que las puntuaciones de las muestras no clínicas. Las puntuaciones en el CFQ estuvieron significativamente correlacionadas con evitación experiencial, síntomas emocionales, mindfulness y satisfacción vital. El CFQ fue sensible a los efectos de una intervención de terapia de aceptación y compromiso de una sesión. Esta versión en español del CFQ mostró buenas propiedades psicométricas en Colombia.

Cognitive fusion is a central construct of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999) – a model of psychopathology and behavioral ineffectiveness. Cognitive fusion is a verbal process whereby individuals become entangled in their thinking and evaluations, judgements and memories and behave according to the derived functions of these private experiences. In other words, private experiences dominate subsequent behavior, thereby preventing other sources of stimulus control from influencing behavior (Gillanders et al., 2014; Luciano, Valdivia-Salas, & Ruiz, 2012; Törneke, Luciano, Barnes-Holmes, & Bond, 2016). When private experiences are aversive, fusion usually leads to experiential avoidance strategies (e.g., suppression, distraction, worry, rumination, etc.) in order to reduce this discomfort. These short term avoidance strategies are thereby negatively reinforced. People will often continue applying experiential avoidance strategies in response to aversive private experiences leading to entrapment in the experiential avoidance loops characteristics of psychological disorders (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996).

For instance, consider the case of a person who begins to derive thoughts concerning the possibility of developing a psychotic disorder because of the similar characteristics between her and a person she has just met who suffer from schizophrenia (e.g., similar personality, interests, physical appearance, etc.). Fused behavior with these thoughts may lead the person to do something like visiting internet webpages to analyze the likelihood of developing schizophrenia, asking for a professional opinion, avoiding conversations about mental disorders, hypervigilant scanning for unusual perceptual experiences, hyper arousal leading to autonomic reactivity, sleep disturbance, etc. At the same time, the person could avoid social stigma associated with mental illness by not sharing these concerns with others, reducing opportunities for reality checking, corrective perspectives, etc. If this pattern of fused behavior with thoughts related to schizophrenia is followed, the person may enter an experiential avoidance loop and stop performing valued actions.

Given the prominence of cognitive fusion in the underlying theory, ACT posits a great emphasis in promoting cognitive defusion, which is the process of taking a detached perspective on private experiences, and unhooking behavior from said events, such that other sources of stimulus control influence behavior in accordance with personal values instead of experiential avoidance (Levin, Luoma, & Haeger, 2015; Törneke et al., 2016).

Given the importance of cognitive fusion, several self-report measures of fusion have been validated in the last few years. These include the Believability of Anxious Feelings and Thoughts (BAFT; Herzberg et al., 2012; Ruiz, Odriozola-González, & Suárez-Falcón, 2014) and the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ; Gillanders et al., 2014). While BAFT is contextualized to anxiety, the CFQ has the advantage that it is a general measure of cognitive fusion that can be applied to diverse situations.

A Spanish version of the CFQ already exists (Romero-Moreno, Márquez-González, Losada, Gillanders, & Fernández-Fernández, 2014), but it was validated in Spain with a relatively small sample of caregivers. Accordingly, further psychometric analyses are needed to explore the properties of the CFQ in more diverse samples and in other Spanish speaking countries. Indeed, testing measures in culturally diverse samples enhances both our confidence in the measure and the cross-cultural relevance of the underlying theory being measured (Elosua, Mujika, Almeida, & Hermosilla, 2014). The current study aimed to analyze the psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the CFQ in Colombia. A small pilot study was first conducted to enhance the cultural sensitivity of the Spanish version of the CFQ. Subsequently, the CFQ was administered to three samples (total N=1763): a sample of 762 undergraduates, a sample of 724 Colombian people recruited through internet, and a clinical sample of 277 participants. An additional small sample (N=11) was used to explore whether the CFQ scores were sensitive to the effect of a 1-session ACT intervention to reduce maladaptive worry and rumination. We expected the CFQ to show similar psychometric characteristics in Colombia the original scale.

MethodParticipantsSample 1. This sample consisted of 762 undergraduates (age range 18–63, M=21.16, SD=3.76) from seven universities of Bogotá. Forty-six percent of the participants in the sample were studying Psychology. The other studies included Law, Engineering, Philosophy, Communication, Business, Medicine, and Theology. Sixty-two percent were women. Of the overall sample, 26% of the participants had received psychological or psychiatric treatment at some time, but only 4.3% were currently in treatment. Also, 2.9% of participants were taking some psychotropic medication.

Sample 2. The sample consisted of 724 participants (74.4% females) with age ranging between 18 and 88 years (M=26.11, SD=8.93). The relative educational level of the participants was 17.8% primary studies (i.e., compulsory education) or mid-level study graduates (i.e., high school or vocational training), 63.8% were undergraduates or college graduates, and 18.4% were currently studying or had a graduate degree. All the participants were Colombian and they responded to an anonymous internet survey distributed through social media. Forty-five percent reported having received psychological or psychiatric treatment at some time, but only 8.4% were currently in treatment. Also, 5.4% of participants reported using psychotropic medication.

Sample 3. Sample three consisted of 277 patients (64.6% of them were women) with an age range of 18–67 years (M=28.50, SD=11.22), suffering from emotional (88.4%) or sexual disorders (11.6%) according to the information gathered from their therapists. All participants were being evaluated in a private psychological consultation center. Only 6.3% of the participants reported that they were using psychotropic medication.

Sample 4. This sample consisted of 11 participants (2 men, mean age=22.18, SD=4.40, age range: 18–32) who participated in a randomized multiple-baseline study that analyzed the effect of a 1-session ACT intervention to disrupt problematic worry and rumination. The relative educational level of the participants was as follows: one with mid-level study graduates, six undergraduate students, and 4 were college graduates. The participants were recruited through advertisements in social media and stated that they had spent at least 6 months entangled in thoughts, memories, and/or worries that provoked significant interference in at least two life areas. They were not receiving psychological or psychiatric treatment. Additional information of the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be seen in Ruiz, Riaño-Hernández, Suárez-Falcón, and Luciano (2016).

InstrumentsCognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ; Gillanders et al., 2014). The CFQ is a 7-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (7=always; 1=never true) that measures general cognitive fusion. Higher scores reflect higher degree of cognitive fusion. The English validation of the CFQ showed that it possesses a one-factor structure, good reliability, temporal stability, convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity, and sensitivity to treatment effects. The CFQ showed strong positive correlations with measures of experiential avoidance, frequency of negative thoughts, depression and anxiety symptoms, burnout, etc. Conversely, CFQ scores showed negative correlations with measures of mindfulness skills and life satisfaction.

The Spanish version by Romero-Moreno et al. (2014) showed a one-factor structure, good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha of .87), and convergent validity. A small pilot study was conducted to enhance the cultural sensitivity of the Spanish version of the CFQ. Specifically, ten Colombian undergraduates were asked to rate item clarity and simplicity, and suggest possible changes to adapt the language to the Colombian culture. The undergraduates rated the items as highly understandable and suggested minor changes to the wording of some items mostly related to gender (it is not very common in Colombia to write sentences including both genders, therefore only the generic masculine was used). Item 7 was slightly changed to more accurately capture the sense of being caught up by thoughts. Table 2 presents the items used in this study (see Table 2).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011; Spanish translation by Ruiz, Langer, Luciano, Cangas, & Beltrán, 2013). The AAQ-II is a 7-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (7=always; 1=never true) that measures general experiential avoidance or psychological inflexibility. The items reflect unwillingness to experience unwanted emotions and thoughts and the inability to be in the present moment and behave according to value-directed actions when experiencing unwanted psychological events. The Spanish version by Ruiz, Suárez-Falcón, Cárdenas-Sierra, et al. (2016) showed good psychometric properties (mean alpha of .90) and a one-factor structure in Colombian samples. In this study, Cronbach's alphas were .88, .91, and .93 for Samples 1–3, respectively. We expected the AAQ-II and CFQ to show very strong positive correlations according to previous evidence (Gillanders et al., 2014).

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns, & Swinson, 1998; Spanish version by Daza, Novy, Stanley, & Averill, 2002). The DASS-21 is a 21-item, 4-point Likert-type scale (3=applied to me very much, or most of the time; 0=did not apply to me at all) consisting of sentences describing negative emotional states. It contains three subscales (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress) and has shown good internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity. Alpha values in this study were good for all subscales (for the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress subscales, respectively, Sample 1: .86, .80, and .80; Sample 2: .92, .85, and .86; Sample 3: .92, .85, and .90). We expected that the CFQ would show strong positive correlations with all the DASS-21 subscales.

Satisfaction with Life Survey (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985; Spanish version by Atienza, Pons, Balaguer, & García-Merita, 2000). The SWLS is a 5-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (7=strongly agree; 1=strongly disagree) that measures self-perceived well-being. The SWLS has good psychometric properties and convergent validity. Alpha values in this study for the SWLS were good (Sample 1: .85; Sample 2: .89; Sample 3: .84). According to previous evidence (Gillanders et al., 2014), we expected medium to strong negative correlations between the SWLS and CFQ scores.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Spanish version by Soler et al., 2012). The MAAS is a 15-item, 6-point Likert-type scale (6=almost never; 1=almost never) designed to measure the extent to which individuals pay attention during several tasks or, in contrast, behave on “autopilot” mode, i.e., without paying enough attention thereto. The MAAS does not require familiarity with meditation. Higher scores indicate greater mindfulness level. The MAAS has shown good psychometric properties and a one-factor structure in a Colombian sample (Ruiz, Suárez-Falcón, & Riaño-Hernández, 2016). Cronbach's alpha of the MAAS in this study was .92. We expected moderate to strong negative correlations between the CFQ and MAAS scores.

Dysfunctional Attitude Scale-Revised (DAS-R; de Graaf, Roelofs, & Huibers, 2009; Spanish version by Ruiz et al., 2015). The DAS is a classic measure of dysfunctional schemata. The revised version of the DAS is a 17-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (7=fully agree; 1=fully disagree) grouped in two factors: Perfectionism/Performance evaluation and Dependency. In a Colombian sample, the DAS-R showed excellent psychometric properties and a factor structure with two-correlated factors and a second-order factor (Ruiz, Suárez-Falcón, Barón-Rincón, et al., 2016). In this study, the DAS-R showed an alpha of .91. According to previous evidence of the relation of dysfunctional schemas with experiential avoidance and cognitive fusion (e.g., Ruiz & Odriozola-González, 2015, 2016), we expected the CFQ and DAS-R to show moderate to strong positive correlations.

ProcedureIn Sample 1, the administration of the questionnaire package was conducted in the participants’ classrooms during the beginning of a regular class. Participants in Sample 2 responded to an anonymous internet survey distributed through social media. Lastly, participants in Sample 3 responded to the questionnaires during one of the clinical assessment interviews at the beginning of the treatment in the presence of their therapist.

In Samples 1–3, the participants provided informed consent and were provided with a questionnaire packet. Participants in Sample 1 responded to the CFQ, AAQ-II, DASS-21, MAAS, DAS-R, and SWLS. Participants in Samples 2 and 3 responded to the CFQ, AAQ-II, SWLS, and DASS-21. Upon completion of the study, the participants were debriefed about the aims of the study and thanked for their participation.

The participants in Sample 4 completed a baseline period ranging between 2 and 10 weeks and then received an ACT intervention specifically oriented to disrupt problematic worry and rumination. After that, the participants completed follow-up measures for 6 weeks. The ACT protocol consisted of an approximately 75-min, individual session. The main objectives of the protocol were: (a) to identify triggers for worrying/ruminating and experiential avoidance strategies related to them, (b) to promote creative hopelessness regarding the counterproductive effect of engaging in worry/rumination and the other experiential avoidance strategies, (c) to promote values clarification and the commitment to valued actions, and (d) to introduce defusion training.

Data analysisPrior to conducting factor analyses, data from Samples 1 to 3 were screened for missing values. Only two values of the CFQ were missing (one for item 1 and 6, respectively). These data were imputed using the matching response pattern method of LISREL© (version 8.71, Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1999), which was the software used to conduct the confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). In this imputation method, the value to be substituted for the missing value of a single case is obtained from another case (or cases) having a similar response pattern over the seven items of the CFQ.

Because the CFQ uses a Likert-type scale measured on an ordinal scale, a weighted least squares (WLS) estimation method using polychoric correlations was used in conducting CFA. The WLS method is recommended in large samples with fewer than 20 items as in the current study (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1996). We computed the chi-square test and the following goodness of fit indexes for the one-factor model: (a) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); (b) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI); and (c) the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI). According to Kelloway (1998) and Hu and Bentler (1999), RMSEA values below .10 represent an acceptable fit, and values below .05 represent a very good fit to the data. With respect to the CFI and NNFI, values above .90 indicate acceptable-fitting models, and above .95 represent a good fit to the data.

As in Gillanders et al. (2014), additional CFA were performed to test for measurement invariance across samples and gender. In other words, we analyzed whether the item factor loadings are invariant across the three samples and between men and women. In so doing, the relative fit of two models was compared. The first model (the multiple-group baseline model) allowed the seven unstandardized factor loadings to vary across the three samples and across men and women, whereas the second model (constrained model) placed equality constraints (i.e., invariance) on those loadings. Equality constraints were not placed on estimates of the factor variances because these are known to vary across groups even when the indicators are measuring the same construct in a similar manner (Kline, 2005). The parsimonious model (constrained model) would be selected if the following four criteria suggested by Cheung and Rensvold (2002) and Chen (2007) were met: (a) the constrained model did not generate a significantly worse fit than the unconstrained model (the multiple-group baseline model) according to the chi-square test; (b) the difference in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) was lower than .01; (c) the difference in CFI (ΔCFI) was greater than −.01; and (d) the difference in NNFI (ΔNNFI) was greater than −.01.

The remaining statistical analyses were performed on SPSS 19©. Cronbach's alphas were computed providing 95% confidence intervals (CI) to explore the internal consistency of the CFQ in Samples 1 to 3 and the overall sample. Corrected item-total correlations were obtained to identify items that should be removed because of low discrimination item index (i.e., values below .20). Descriptive data were also calculated, and gender differences in CFQ scores were explored by computing Student's t. To examine criterion validity, scores on the CFQ were compared between participants in Sample 1 and 2 (nonclinical participants) to participants in Sample 3 (clinical participants). Pearson correlations between the CFQ and other scales were calculated to assess convergent construct validity. Lastly, to explore whether the CFQ scores were sensitive to the effects of a 1-session ACT intervention, Student's t-tests for dependent data were conducted between the last CFQ score of participants’ baseline and the 6-week follow-up. Cohen's d for within-participant studies was also computed.

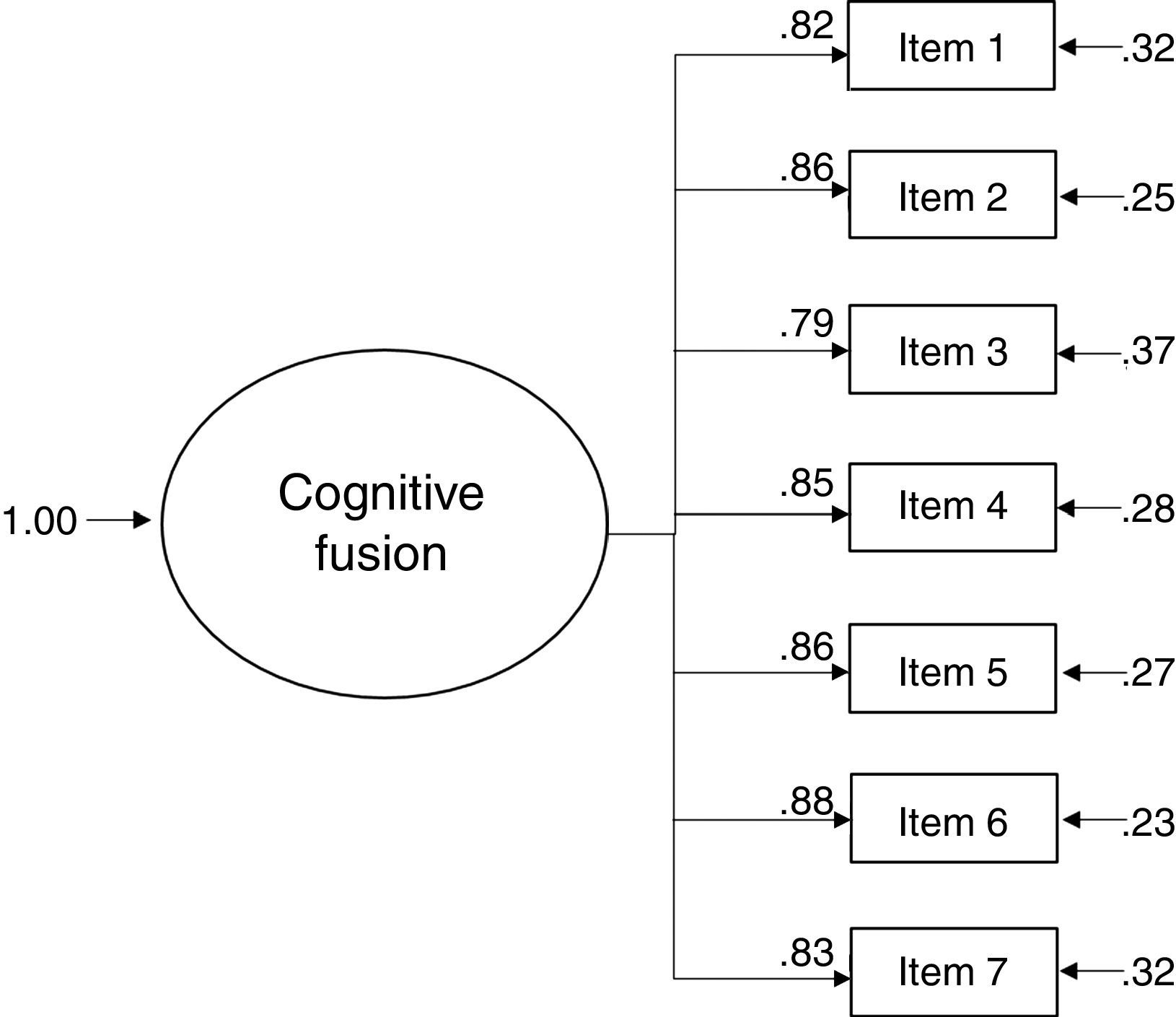

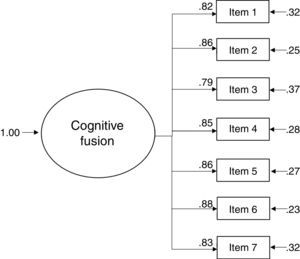

ResultsFactor structureThe fit of the one-factor model found in Gillanders et al. (2014) was adequate for all samples and the goodness-of-fit indexes were good (Sample 1: χ2=53.17, df=14, p<.01; RMSEA=.061, 90% CI [.044, .078]; CFI=.98; NNFI=.97; Sample 2: χ2=72.40, df=14, p<.01; RMSEA=.076, 90% CI [.059, .094]; CFI=.99; NNFI=.98; Sample 3: χ2=30.44, df=14, p<.01; RMSEA=.065, 90% CI [.033, .097]; CFI=.99; NNFI=.99). For the overall sample, the goodness-of-fit indexes were also good (χ2=135.56, df=14, p<.01; RMSEA=.070, 90% CI [.060, .081]; CFI=.98; NNFI=.98). Fig. 1 depicts the results of the standardized solution of the one-factor model.

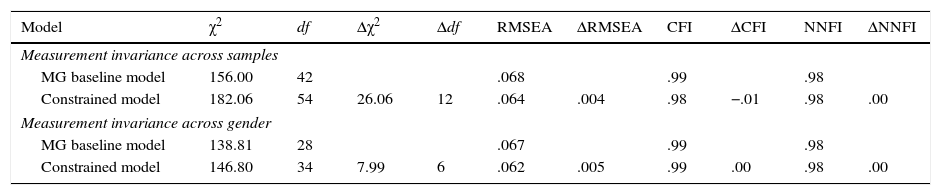

Measurement invarianceTable 1 shows that the multiple-group baseline models fit the data well, with all values of the goodness-of-fit indexes suggesting good-fitting solutions. When equality constraints were placed on the factor loadings, there was no significant decrement in goodness of fit, suggesting that the measures were invariant across samples and gender. With respect to measurement invariance across samples, all the criteria recommended by Cheung and Rensvold (2002) and Chen (2007) were met. Specifically, the χ2 diff test was not statistically significant (χ2(12)=26.06, p>.01), the differences in RMSEA were lower than .01, and the differences in CFI and NNFI were higher than −.01. All criteria were also met in relation to measurement invariance across gender (χ2(6)=7.99, p>.01).

Measurement invariance across samples and gender.

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δdf | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | CFI | ΔCFI | NNFI | ΔNNFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement invariance across samples | ||||||||||

| MG baseline model | 156.00 | 42 | .068 | .99 | .98 | |||||

| Constrained model | 182.06 | 54 | 26.06 | 12 | .064 | .004 | .98 | −.01 | .98 | .00 |

| Measurement invariance across gender | ||||||||||

| MG baseline model | 138.81 | 28 | .067 | .99 | .98 | |||||

| Constrained model | 146.80 | 34 | 7.99 | 6 | .062 | .005 | .99 | .00 | .98 | .00 |

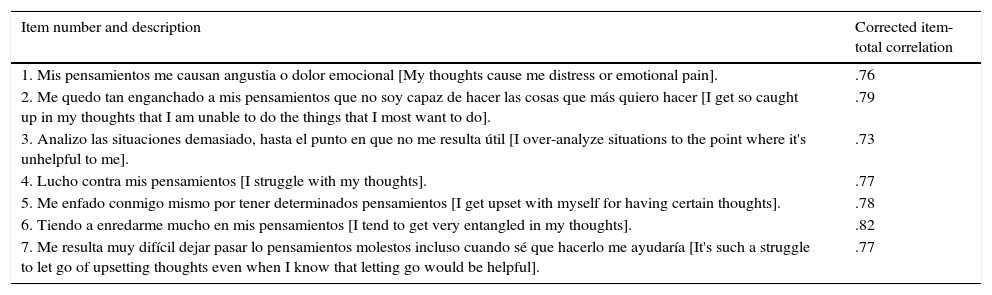

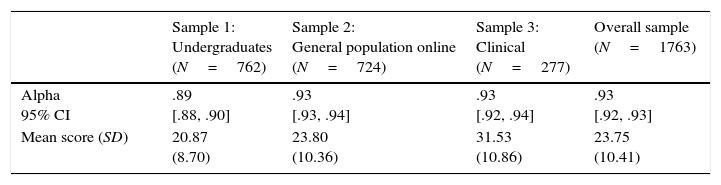

Table 2 shows that Cronbach's alpha of the CFQ ranged from .89 (Sample 1) to .93 (Sample 3), with an overall alpha of .93. Corrected item-total correlations of the CFQ ranged from .67 to .72 in Sample 1, from .76 to .80 in Sample 2, and from .73 to .85 in Sample 3. Table 3 shows the original items, their translation into Spanish, and corrected item-total correlations for the overall sample.

Item description and corrected item-total correlations.

| Item number and description | Corrected item-total correlation |

|---|---|

| 1. Mis pensamientos me causan angustia o dolor emocional [My thoughts cause me distress or emotional pain]. | .76 |

| 2. Me quedo tan enganchado a mis pensamientos que no soy capaz de hacer las cosas que más quiero hacer [I get so caught up in my thoughts that I am unable to do the things that I most want to do]. | .79 |

| 3. Analizo las situaciones demasiado, hasta el punto en que no me resulta útil [I over-analyze situations to the point where it's unhelpful to me]. | .73 |

| 4. Lucho contra mis pensamientos [I struggle with my thoughts]. | .77 |

| 5. Me enfado conmigo mismo por tener determinados pensamientos [I get upset with myself for having certain thoughts]. | .78 |

| 6. Tiendo a enredarme mucho en mis pensamientos [I tend to get very entangled in my thoughts]. | .82 |

| 7. Me resulta muy difícil dejar pasar lo pensamientos molestos incluso cuando sé que hacerlo me ayudaría [It's such a struggle to let go of upsetting thoughts even when I know that letting go would be helpful]. | .77 |

Cronbach's alphas and descriptive data across samples.

| Sample 1: Undergraduates (N=762) | Sample 2: General population online (N=724) | Sample 3: Clinical (N=277) | Overall sample (N=1763) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha 95% CI | .89 [.88, .90] | .93 [.93, .94] | .93 [.92, .94] | .93 [.92, .93] |

| Mean score (SD) | 20.87 (8.70) | 23.80 (10.36) | 31.53 (10.86) | 23.75 (10.41) |

The mean score of men (M=19.90, SD=8.21) in Sample 1 was slightly lower than that of women (M=21.49, SD=8.94), with a statistically significant difference (t=−2.46, p=.014). No statistically significant differences (t=1.86, p=.06) were found in Sample 2 between men (M=25.05, SD=10.30) and women (M=23.36, SD=10.35). Likewise, no statistically significant differences were found in Sample 3 with relation to sex (men: M=30.43, SD=11.87; women: M=32.20, SD=10.24; t=−1.23, p=.22). The mean score of participants in the clinical sample (Sample 3) was higher than those of participants in Sample 1 (t=−14.71, p<.001) and Sample 2 (t=−10.42, p<.001).

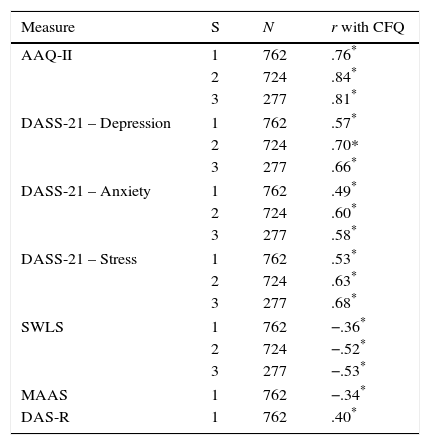

Pearson correlations with other related constructsThe CFQ showed correlations with all the other assessed constructs in theoretically coherent ways (see Table 4). Specifically, the CFQ showed positive correlations with psychological inflexibility (AAQ-II), depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (DASS-21), and dysfunctional attitudes; and negative correlations with mindful awareness (MAAS), and satisfaction with life (SWLS).

Pearson correlations between the CFQ scores and other relevant self-report measures.

| Measure | S | N | r with CFQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAQ-II | 1 | 762 | .76* |

| 2 | 724 | .84* | |

| 3 | 277 | .81* | |

| DASS-21 – Depression | 1 | 762 | .57* |

| 2 | 724 | .70* | |

| 3 | 277 | .66* | |

| DASS-21 – Anxiety | 1 | 762 | .49* |

| 2 | 724 | .60* | |

| 3 | 277 | .58* | |

| DASS-21 – Stress | 1 | 762 | .53* |

| 2 | 724 | .63* | |

| 3 | 277 | .68* | |

| SWLS | 1 | 762 | −.36* |

| 2 | 724 | −.52* | |

| 3 | 277 | −.53* | |

| MAAS | 1 | 762 | −.34* |

| DAS-R | 1 | 762 | .40* |

Note: AAQ-II: Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; CFQ: Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire; DAS-R: Dysfunctional Attitude Scale-Revised; DASS: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21; MAAS: Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale.

In Sample 4, the participants’ mean score in the last baseline assessment was 30.27 (SD=7.56), whereas the mean score at the 6-week follow-up was 19.36 (SD=7.63). The difference was statistically significant and with a very large effect size (t=6.23, p<.001, d=1.89).

DiscussionIn order to advance in the research of the ACT model, several attempts to measure cognitive fusion have been proposed during the last years such as the BAFT and CFQ. The CFQ has the advantage that it is a general measure of cognitive fusion. Although a Spanish version of the CFQ already existed, its psychometric properties were explored only in a small sample of caregivers in Spain. Accordingly, the current study aimed to analyze the psychometric properties and factor structure of the CFQ in Colombia after conducting a small pilot study to enhance the cultural sensitivity of the Spanish version.

The data obtained showed that this Spanish version of the CFQ had good psychometric properties in Colombia. Specifically, the CFQ showed construct validity to the extent that factor analysis showed the same one-factor solution as in Gillanders et al. (2014). Criteria for measurement invariance across gender and samples (undergraduates, general population, and clinical participants) were completely met. The internal consistency of the CFQ was very good with an overall alpha of .93 and it showed criterion validity to the extent that its scores discriminated between clinical and nonclinical samples. The instrument also showed convergent validity in view of the positive correlations found with psychological inflexibility and emotional symptoms, and the negative correlations with mindfulness and life satisfaction. Lastly, the CFQ was shown to be sensitive to the effect of a 1-session ACT intervention with people suffering from problematic worry and rumination.

Some limitations of this study are worth mentioning. Firstly, no systematic information was obtained concerning the specific diagnosis in clinical participants, as they were categorized in broad categories such as emotional and sexual disorders. Secondly, some of the instruments used to explore the convergent and divergent validity of the CFQ lacked formal validation in Colombian samples (DASS-21 and SWLS). However, their internal consistencies were adequate and similar to the ones obtained in the original language validation studies. Thirdly, the percentage of women was higher across all samples. However, statistical analyses showed that measurement invariance analyses showed that CFQ was invariant across gender.

In addition to showing the adequacy of measurement of the CFQ in the Colombian population, the data presented here adds to the growing body of research that shows the cross cultural relevance of the concept of cognitive fusion. Measure development and theory development proceed hand in hand: when we have good measures we can test the boundary conditions of a theory. One such boundary condition is the applicability of a model across diverse cultural and ethnic contexts. The CFQ has been reviewed by peers, and it has shown to have good psychometric properties in English (Gillanders et al., 2014), Spanish (Romero-Moreno et al., 2014), Catalan (Solé et al., in press), Chinese (Wei-Chen, Yang, Li, Hui-Na, & Zhuo-Hong, 2014), and versions are currently under review in French (Dionne et al., in press). Furthermore, whilst not yet available in peer reviewed journals, data has been presented in conference presentations and on the Association for Contextual Behavioural Science website at www.contextualscience.org/CFQ. These data describe versions in Italian (Dell’Orco, Prevedini, Oppo, Presti, & Moderato, 2012), Dutch, Farsi, Turkish, Polish, and Greek. The data now gathered across several countries shows that cognitive fusion appears to be an important construct related to psychological disorder and behavioral influence and that it can be considered to be broadly applicable across diverse cultures, languages and problem areas.

In conclusion, this Spanish version of the CFQ can be used to measure cognitive fusion in Colombia according to the reliability and validity data provided in this study. Cognitive fusion appears to be an important process that is widely applicable.