Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a pulmonary disorder caused by hypersensitivity mechanisms against antigens released by Aspergillus species, colonizing the airways.

We present the case of a 16-year-old male with a history of asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis with a history of 15 months of cough with purulent sputum, intermittent fever and dyspnea. Thoracic tomography showed bronchiectasis accompanied by mucus impaction. He was treated with different antibiotics and steroid regimens, without a favorable clinical response. The presence of eosinophilia in the peripheral blood, immunoglobulin E Total, skin tests for Aspergillus positive guided the diagnosis of ABPA. Treatment with prednisone plus itraconazole was started, with remission of symptoms.

ABPA should be suspected in patients with asthma with poor response to treatment and alteration in radiologic studies. Treatment includes systemic steroids and avoiding exposure to Aspergillus.

La aspergilosis broncopulmonar alérgica (ABPA) es un trastorno pulmonar causado por mecanismos de hipersensibilidad contra antígenos liberados por especies de Aspergillus, que colonizan las vías respiratorias.

Presentamos el caso de un varón de 16 años con antecedentes de asma y rinoconjuntivitis alérgica con historia de 15 meses de tos con esputo purulento, fiebre intermitente y disnea. La tomografía torácica reporto bronquiectasias acompañadas de impactación de moco. Se le trató con diferentes regímenes de antibióticos y esteroides, sin tener una respuesta clínica favorable. La presencia de eosinófilia en la sangre periférica, inmunoglobulina E Total elevada y pruebas cutáneas para Aspergillus positivo guiaron el diagnóstico de ABPA. Se inició tratamiento con prednisona más itraconazol, con remisión de los síntomas.

Debe sospecharse ABPA en pacientes con asma con mala respuesta al tratamiento y alteración en los estudios radiológicos. El tratamiento incluye esteroides sistémicos y evitar la exposición a Aspergillus.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a pulmonary disorder caused by a hypersensitivity mechanisms type I, III and IV against antigens released by Aspergillus species, colonizing the airways of patients mainly with asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF).1,2

In predisposed individuals, disease occurs following colonization of the bronchi by Aspergillus conidia. The fungal hyphae extend, and allergens are released, leading to persistent airway inflammation resulting in excessive viscous mucous production and impaired mucociliary function. ABPA is clinically characterized by poorly controlled asthma, recurrent pulmonary infiltrates, and bronchiectasis, in some cases can leading to pulmonary fibrosis.3

In Mexico, its prevalence is unknown, however different case reports have been published.4 It is estimated that ABPA affects 12.9% (2–32%) of the asthmatic population; in steroid-dependent asthmatics the prevalence is thought to be 7–14%.5,6 It occurs with equal frequency in both sexes. Most patients are less than 35 years old at the time of diagnosis.7

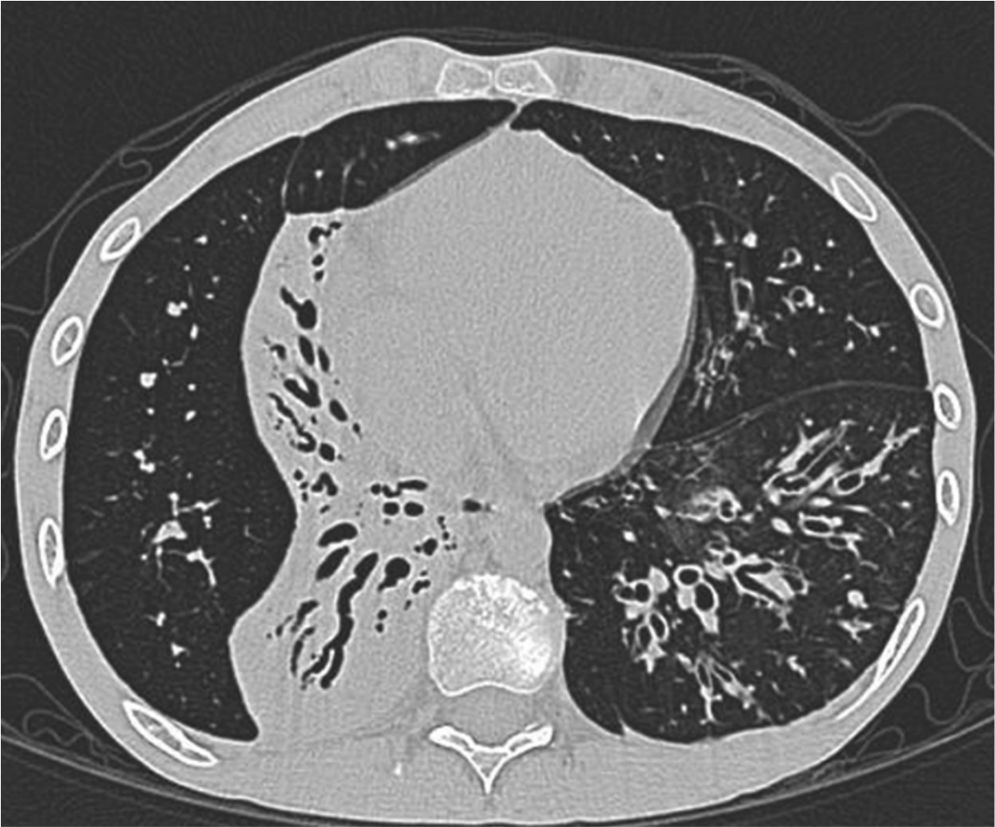

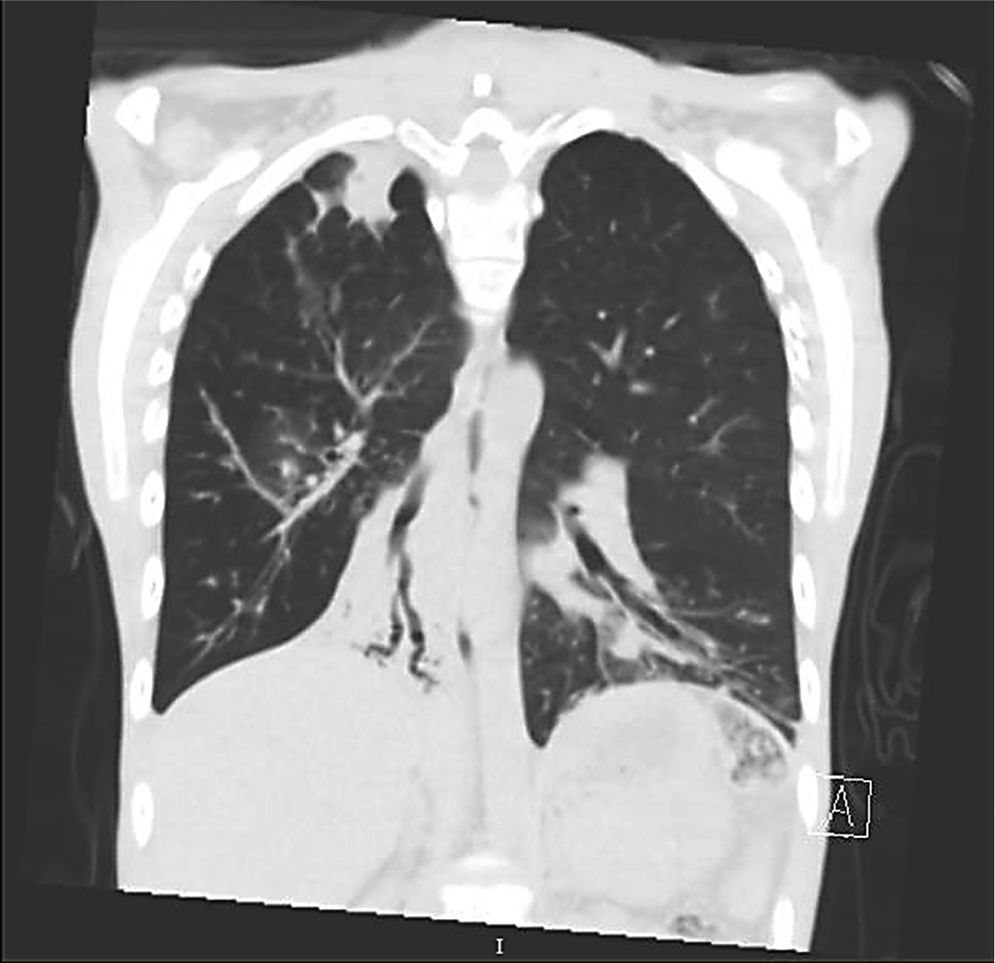

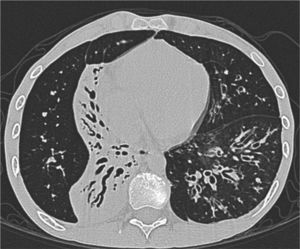

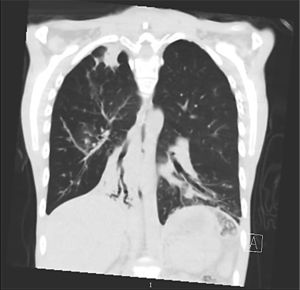

Clinical case presentationA 16 year old male patient with a previous diagnosis of asthma and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis since he was 6 years old, is evaluated in our department of allergy and immunology having history of 15 months of cough with purulent sputum, intermittent fever, progressive dyspnea and acrocianosis. Six months after onset of symptoms he was hospitalized in pediatric unit for 2 months with diagnosis of pneumonia, treated with different antibiotics. The chest X-rays showed a reticular pattern accompanied by images suggesting bronchiectasis, computed tomography of the lungs confirmed central bronchiectasis, accompanied by mucoid impaction and reticular infiltrates (see Figs. 1–3).

X-ray chest shows right posterior basal segmental atelectasis, the lungs present diffuse interstitial reticulum infiltrates, inflammatory infiltrates in the left lung base, bronchiectasis in principal and segmental bronchi, associated right pleural effusion. In addition, right subdiaphragmatic intestinal loops (Chilaiditi syndrome).

Coronary reconstruction with window for pulmonary parenchyma in which consolidation is observed in the right upper lobe and parenchymal bands. Atelectasis with mucus impaction in the right lower lobe. In the lower left lobe there is consolidation, thickening of the wall of the main bronchus.

Due to poor response to treatment, were performed multiple studies among them: sputum smear microscopy in 3 determinations negative, tuberculin test negative, Chlorine test in the sweat (Chlorimetry and conductivity) two determinations negative, the flow cytometry and the nitroblue tetrazolium test were within normal limits, the immunoglobulins were not compatible with some pattern of Immunodeficiency, so it was ruled out that it was pulmonary tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis or some primary immunodeficiency.

An attempt was made to perform fiberoptic bronchoscopy but patient presented significant desaturation during the procedure, which impeded the conclusion of the procedure and take samples.

He was discharged with mild clinical improvement and oxygen dependence, Nine months after discharge was evaluated in our service of allergy and immunology, were performed the following studies: Blood peripheral eosinophils 9.1% (absolut # 700), total IgE: 455IU/mL (NV: <150), specific IgG for Aspergillus fumigatus 4.19mgA/L (NV: <2.0), sputum cytology studies reported polymorphonuclear cells 3+, eosinophils 3+, negative sputum culture for fungi, positive skin prick tests for Aspergillus fumigatus, Chenopodium album, Prosopis spp., Fraxinus americana, Dermatophagoides spp.

Respiratory Functional Tests demonstrated a very severe flow obstruction without response to bronchodilator (Albuterol) with data suggesting pulmonary distention and increased resistance and severely decreased diffusion. With the clinical and laboratory data, we concluded that the patient had allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis stage 1. Treatment was started with prednisone at 1mg/kg/day for 2 weeks then 0.5mg/kg/day for 12 weeks and tritrated to 5mg/day.

He was kept with prednisone 5mg/day for a year, combined with itraconazole 200mg/day for 6 months, salmeterol/fluticasone 50/500μg bid. The patient was evaluated in a month and then every 2 months, at 6 months follow-up had significant clinical improvement. He had suspended supplemental oxygen and returned to normal activities at home and at school.

DiscussionABPA should be suspected in patients with asthma who have a poor response to usual treatment since an appropriate management can cause an impact on quality of life because ABPAs symptoms may be severe and leading to pulmonary fibrosis.

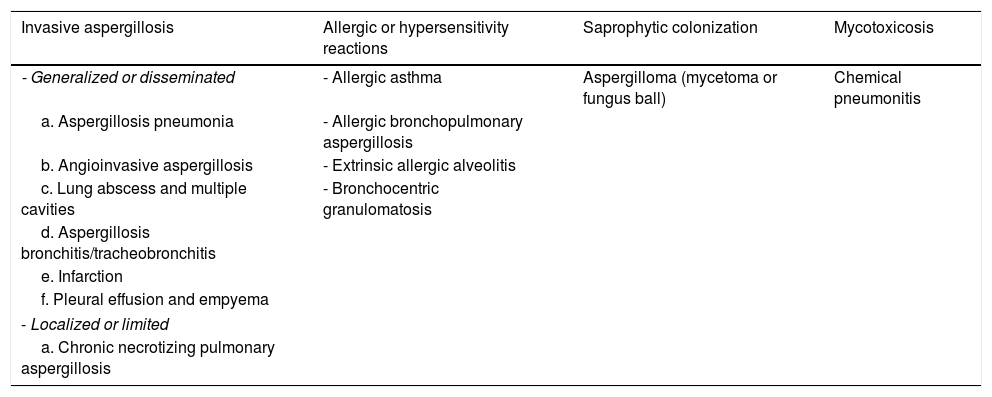

Aspergillus-related pulmonary disorders may be classified into four clinical categories depending on whether the host is atopic, non-atopic or immunosuppressed (see Table 1),7 Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is seem in patients with severe neutropenia, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, prolonged use of systemic steroids, treatment with immunosuppressants and primary immunodeficiency, our patient did not have any of these conditions.8

Pulmonary aspergillosis clinical syndromes.

| Invasive aspergillosis | Allergic or hypersensitivity reactions | Saprophytic colonization | Mycotoxicosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| - Generalized or disseminated | - Allergic asthma | Aspergilloma (mycetoma or fungus ball) | Chemical pneumonitis |

| a. Aspergillosis pneumonia | - Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis | ||

| b. Angioinvasive aspergillosis | - Extrinsic allergic alveolitis | ||

| c. Lung abscess and multiple cavities | - Bronchocentric granulomatosis | ||

| d. Aspergillosis bronchitis/tracheobronchitis | |||

| e. Infarction | |||

| f. Pleural effusion and empyema | |||

| - Localized or limited | |||

| a. Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis | |||

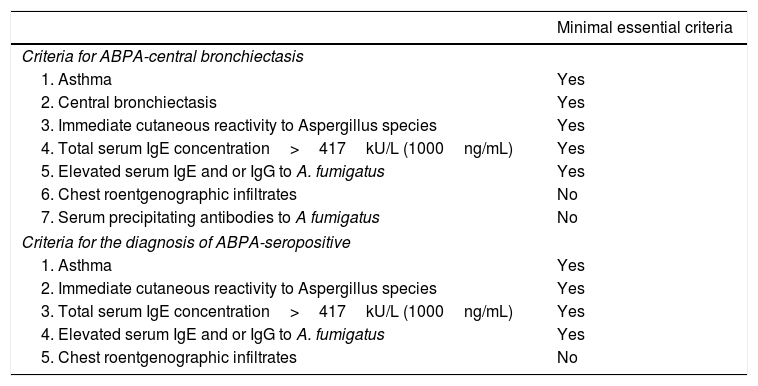

ABPA is commonly caused by A. fumigatus, an ubiquitous mold common in indoors and frequently found around farm buildings and compost heaps. It is a Th2 hypersensitivity lung disease caused by bronchial colonization with A. fumigatus, characterized by asthma exacerbations, recurrent transient chest radiographic infiltrates, peripheral and pulmonary eosinophilia, especially during an exacerbation. Diagnosis is based on clinical and immunologic criteria for ABPA, standardized by Greenberger and Patterson: (1) asthma or CF with deterioration in lung function, (2) Aspergillus species immediate skin test reactivity, (3) total serum IgE level of 1000ng/mL (417IU/mL) or greater, (4) increased specific IgE and IgG antibodies for Aspergillus species-, and (5) chest radiographic infiltrates. Additional criteria modified might include peripheral blood eosinophilia, Aspergillus species serum precipitating antibodies, central bronchiectasis, and Aspergillus species-containing mucus plugs9–11 (see Table 2). The case that we presented complied with the 5 criteria according to original criteria of Greenberger and Patterson, complying for both central bronchiectasis and for seropositive ABPA.

Criteria for the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with asthma.

| Minimal essential criteria | |

|---|---|

| Criteria for ABPA-central bronchiectasis | |

| 1. Asthma | Yes |

| 2. Central bronchiectasis | Yes |

| 3. Immediate cutaneous reactivity to Aspergillus species | Yes |

| 4. Total serum IgE concentration>417kU/L (1000ng/mL) | Yes |

| 5. Elevated serum IgE and or IgG to A. fumigatus | Yes |

| 6. Chest roentgenographic infiltrates | No |

| 7. Serum precipitating antibodies to A fumigatus | No |

| Criteria for the diagnosis of ABPA-seropositive | |

| 1. Asthma | Yes |

| 2. Immediate cutaneous reactivity to Aspergillus species | Yes |

| 3. Total serum IgE concentration>417kU/L (1000ng/mL) | Yes |

| 4. Elevated serum IgE and or IgG to A. fumigatus | Yes |

| 5. Chest roentgenographic infiltrates | No |

CT, computed tomography.

Galactomannan (GM) detection contributes to the diagnosis of IA, even form part of the diagnostic criteria, however for ABPA Agarwal et al. suggest that serum GM estimation has a limited role in the diagnostic workup.8,12

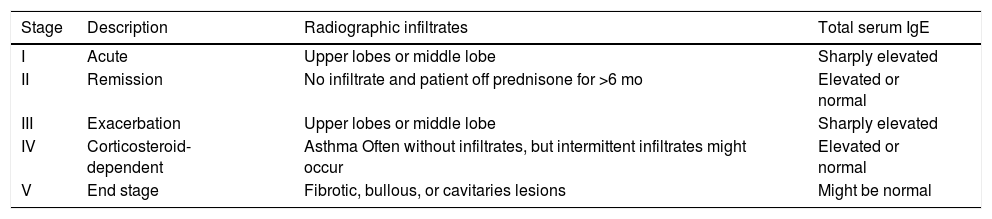

ABPA can be divided into five stages, each stage representing a different category of presentation (Table 3). Determining the stage in which the patient is important for treatment and prognosis.13 Our patient was in stage 1 of the disease.

Stages of ABPA.

| Stage | Description | Radiographic infiltrates | Total serum IgE |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Acute | Upper lobes or middle lobe | Sharply elevated |

| II | Remission | No infiltrate and patient off prednisone for >6 mo | Elevated or normal |

| III | Exacerbation | Upper lobes or middle lobe | Sharply elevated |

| IV | Corticosteroid-dependent | Asthma Often without infiltrates, but intermittent infiltrates might occur | Elevated or normal |

| V | End stage | Fibrotic, bullous, or cavitaries lesions | Might be normal |

The aim of treatment in ABPA is to reduce episodic acute inflammation, thus limiting disease progression with resultant airway destruction and both parenchymal and airway fibrosis. To achieve this, a dual treatment approach is required: corticosteroids to control immunological activity and antifungal azole agents to suppress Aspergillus colonization and proliferation, which reduce antigenic stimulation, limiting further inflammation. However, reviews have emphasized the weakness of the evidence for safety and efficacy of azoles, with only two small, short-term, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in asthmatic ABPA, and none in cystic fibrosis ABPA. There are potential alternative approaches to antifungal treatment that avoid systemic effects, azole resistance and drugs interactions; Inhaled amphotericin B has been explored as an ABPA treatment with varying results in uncontrolled studies. Finally, the success of omalizumab (anti-IgE monoclonal antibody) in improving control of moderate–severe allergic asthma has led to great interest and rapidly increasing usage in ABPA, usually undertaken as a steroid-sparing agent, with virtually unanimous reporting of reduced steroid requirements and exacerbations in published uncontrolled studies.14–20

Our patient had a good response with combined treatment with prednisone and itraconazole, with clinical improvement. He stopped using supplemental oxygen and six months later of start treatment was able to return to previous physical activities. On last visit, we were able to stop prednisone and was only using inhaled sameterol/fluticasone 50/250μg bid.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.