A diet deficient in iron, vitamin B9 (folic acid) and/or vitamin B12 (cobalamin) can affect erythropoiesis and cause anaemia. Treatment consists in the administration of supplements to compensate for dietary deficiencies and build up body reserves. Pharmacological treatment should be complemented by a diet designed to supply the micronutrients lacking in food. Patients should continue to follow the diet even after completing their therapy in order to prevent a recurrence of deficiency anaemia.

Nutritionists should understand deficiency anaemia, and physicians, particularly general practitioners, should be aware of dietary requirements. In this article, therefore, both health care professionals have come together to briefly explain, with examples, the type of diet that should be recommended to patients with deficiency anaemia.

Una dieta deficiente en hierro, vitamina B9 (folato) y/o vitamina B12 (cobalamina) ocasiona alteraciones en la eritropoyesis causando una anemia. El tratamiento se basa en administrar suplementos exógenos a fin de cubrir el déficit y restaurar las reservas corporales. Como complemento al manejo farmacológico debe diseñarse una dieta que facilite la disponibilidad de los micronutrientes en carencia en los alimentos durante el tratamiento y aun cuando éste termine, con la finalidad que el paciente conserve estos hábitos alimenticios y evite futuros eventos de anemia carencial.

Los nutriólogos deben dominar el tema y no debe ser ajeno para los médicos, especialmente para el médico general, por lo cual el presente trabajo fue elaborado de forma conjunta por ambos profesionistas, a fin de servir al lector como una guía rápida con ejemplos concretos de dietas para este tipo de pacientes.

Deficiency anaemias are a group of diseases caused by a diet lacking in the essential nutrients needed for erythropoiesis: iron, vitamin B12 and folic acid (vitamin B9).1 These anaemias are usually found in malnourished elderly individuals, young people following weight loss regimens, and individuals in the low-income range, or with a comorbid condition (for example, incomplete dentition) that prevents them from following a healthy diet. It is also prevalent at certain stages in life, such as pregnancy, breast feeding, childhood and adolescence, when bodily nutritional requirements increase.2

Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anaemia worldwide, accounting for around 50% of all cases.3 This is followed by megaloblastic anaemia caused by a diet deficient in B-group vitamins.2

The best and most sustainable strategy for preventing micronutrient deficiency is dietary improvement. Dietary changes can also act as a complement to pharmacological therapy, either by providing additional nutrients or by preventing adverse interactions between dietary supplements and food. Despite efforts to raise awareness of the need for dietary changes in these patients, most practitioners do not know which foods are really effective in correcting each type of anaemia.4 This is further aggravated by widely held popular misconceptions or the out-dated scientific belief that iron-rich vegetables such as spinach or chard are good for anaemia, without considering the bioavailability of the inorganic (non-heme) iron in these vegetables and the limited capacity of the human digestive system to absorb it.5 Sotelo et al. made a major contribution to this topic by analysing the vegetables most widely consumed in Mexico. The group found high concentrations not only of iron, but also of oxalate, tannins and phytates, which interact with iron and other proteins to form complexes that are hard to digest and prevent absorption.6

In the following paragraphs we will give a brief overview of nutritional recommendations for patients with deficiency anaemia.

Iron deficiencyIron is the second most abundant metal in the earth's crust. It is essential for life due to its role in nearly all redox reactions, and is a vital component in several bodily function, primarily haemoglobin synthesis and transport of oxygen throughout the body.7

A normal diet contains around 6mg of iron for every 1000 calories. This gives a daily iron intake of between 13 and 20mg, of which between 5% and 15% of iron in ferrous form is absorbed by the duodenum and upper jejunum (1–2mg/day).8

Adult men and postmenopausal women need 8mg of iron per day. Breast feeding mothers need 9mg/day, or 10mg/day in the case of an adolescent mother (14–18 years). Adolescent boys need at least 11mg/day of iron. Adolescent girls need 15/mg/day; a requirement that increases to 18mg/day in women aged over 18 years, and persists until they reach the menopause. Iron intake requirements reach a peak in pregnant women, both adolescent and adult, who need 27mg/day. In all the foregoing cases, iron intake should never exceed 45mg/day.9,10

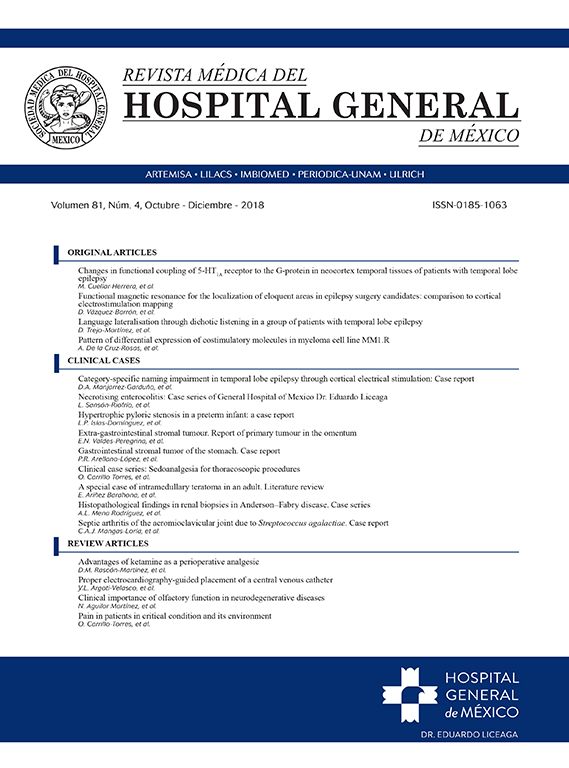

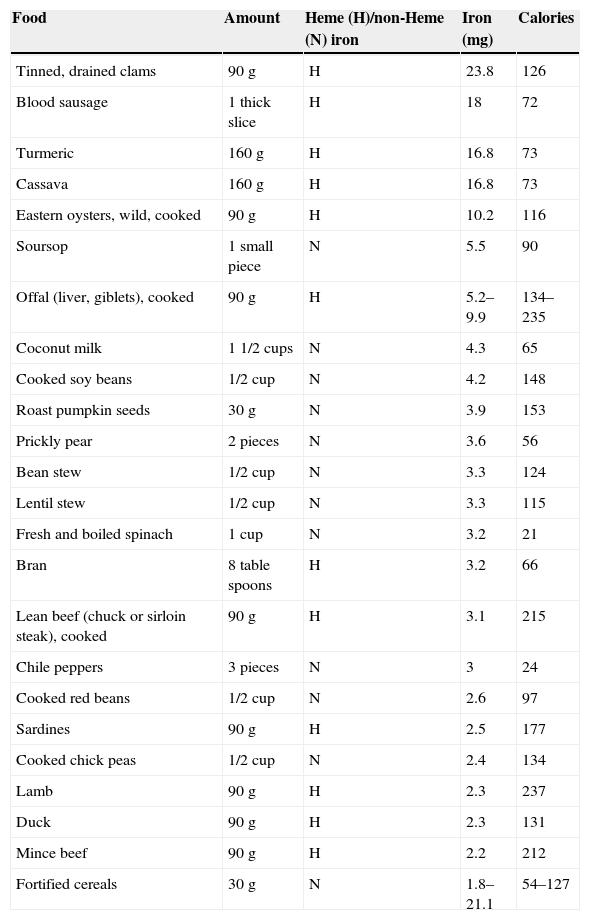

Iron is present in the diet in 2 forms: heme (organic), of which 15–25% is absorbed, is commonly found in red meat, fish and poultry, and non-heme (inorganic), usually found in pulses, grains and fruit, of which only 5–20% is absorbed.9Table 1 shows the primary source of dietary iron.11Fig. 1 shows an example of a balanced diet capable of providing 26.1mg/day of iron.

Dietary sources of iron.

| Food | Amount | Heme (H)/non-Heme (N) iron | Iron (mg) | Calories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tinned, drained clams | 90g | H | 23.8 | 126 |

| Blood sausage | 1 thick slice | H | 18 | 72 |

| Turmeric | 160g | H | 16.8 | 73 |

| Cassava | 160g | H | 16.8 | 73 |

| Eastern oysters, wild, cooked | 90g | H | 10.2 | 116 |

| Soursop | 1 small piece | N | 5.5 | 90 |

| Offal (liver, giblets), cooked | 90g | H | 5.2–9.9 | 134–235 |

| Coconut milk | 1 1/2 cups | N | 4.3 | 65 |

| Cooked soy beans | 1/2 cup | N | 4.2 | 148 |

| Roast pumpkin seeds | 30g | N | 3.9 | 153 |

| Prickly pear | 2 pieces | N | 3.6 | 56 |

| Bean stew | 1/2 cup | N | 3.3 | 124 |

| Lentil stew | 1/2 cup | N | 3.3 | 115 |

| Fresh and boiled spinach | 1 cup | N | 3.2 | 21 |

| Bran | 8 table spoons | H | 3.2 | 66 |

| Lean beef (chuck or sirloin steak), cooked | 90g | H | 3.1 | 215 |

| Chile peppers | 3 pieces | N | 3 | 24 |

| Cooked red beans | 1/2 cup | N | 2.6 | 97 |

| Sardines | 90g | H | 2.5 | 177 |

| Cooked chick peas | 1/2 cup | N | 2.4 | 134 |

| Lamb | 90g | H | 2.3 | 237 |

| Duck | 90g | H | 2.3 | 131 |

| Mince beef | 90g | H | 2.2 | 212 |

| Fortified cereals | 30g | N | 1.8–21.1 | 54–127 |

Folic acid is mainly absorbed in the jejunum and ileum, the only organs containing the intraluminal enzymes needed to transform the polyglutamates found in folic acid (the form in which they are found in food) into monoglutamates. This is why only 25–50% of dietary vitamin B9 is bioavailable. Enterocytes transform folic acid into methyltetrahydrofolate, which is absorbed by the cells and converted into tetrahydrofolate, the active form of vitamin B9. Tetrahydrofolate has a role in several cellular processes, one of the most important being thymine synthesis, which is essential for the production of nucleic acid.2,9,12

Folic acid supplements are more effective in increasing serum levels than dietary folate. Folate is absorbed by passive transport following intake of large amounts of folic acid. According to guidelines, adults should take 400mcg/day, pregnant women 600mcg/day, and breast-feeding mothers 500mcg/day. In all cases, intake is limited to 1000mcg/day.2,9,12

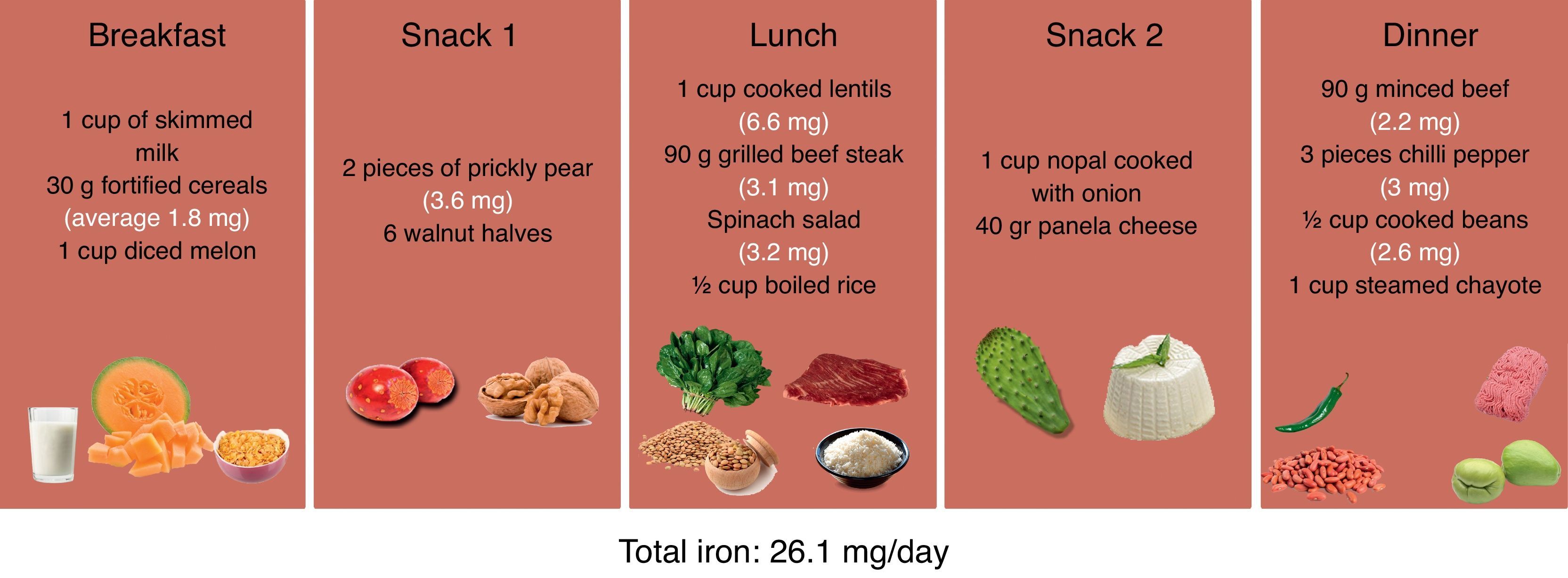

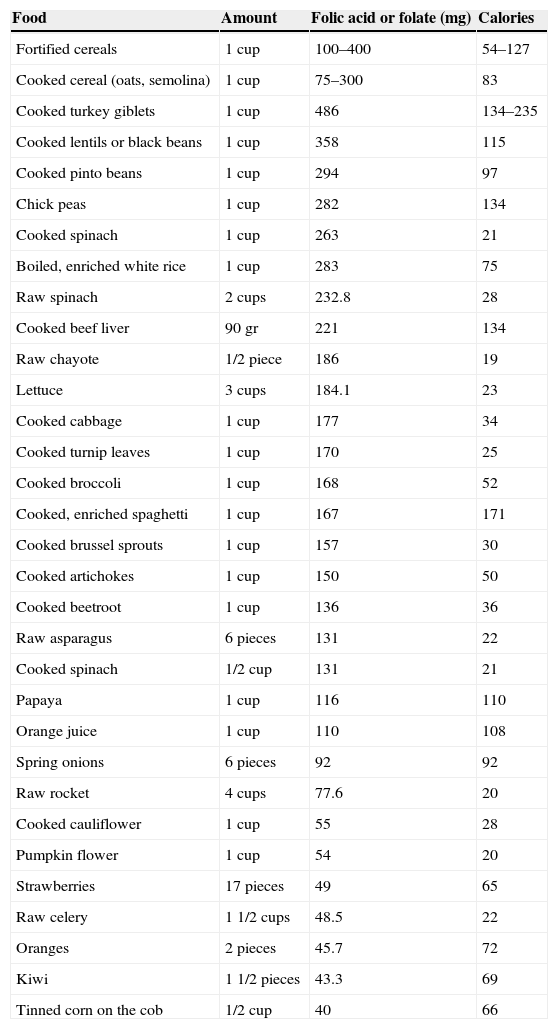

The most folate-rich foods include fortified cereals, red and white pinto beans (cooked), lentils, beetroot, asparagus, spinach, romaine lettuce, broccoli, and oranges. Table 2 shows the folic acid content of various foods.11,13 There are 150 different forms of folate, and between 50% and 90% of dietary folate is lost during storage, cooking or processing at high temperatures.6,12Fig. 2 gives as example of a balanced diet capable of providing 866mcg/day of folic acid.

Dietary sources of folic acid.

| Food | Amount | Folic acid or folate (mg) | Calories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fortified cereals | 1 cup | 100–400 | 54–127 |

| Cooked cereal (oats, semolina) | 1 cup | 75–300 | 83 |

| Cooked turkey giblets | 1 cup | 486 | 134–235 |

| Cooked lentils or black beans | 1 cup | 358 | 115 |

| Cooked pinto beans | 1 cup | 294 | 97 |

| Chick peas | 1 cup | 282 | 134 |

| Cooked spinach | 1 cup | 263 | 21 |

| Boiled, enriched white rice | 1 cup | 283 | 75 |

| Raw spinach | 2 cups | 232.8 | 28 |

| Cooked beef liver | 90 gr | 221 | 134 |

| Raw chayote | 1/2 piece | 186 | 19 |

| Lettuce | 3 cups | 184.1 | 23 |

| Cooked cabbage | 1 cup | 177 | 34 |

| Cooked turnip leaves | 1 cup | 170 | 25 |

| Cooked broccoli | 1 cup | 168 | 52 |

| Cooked, enriched spaghetti | 1 cup | 167 | 171 |

| Cooked brussel sprouts | 1 cup | 157 | 30 |

| Cooked artichokes | 1 cup | 150 | 50 |

| Cooked beetroot | 1 cup | 136 | 36 |

| Raw asparagus | 6 pieces | 131 | 22 |

| Cooked spinach | 1/2 cup | 131 | 21 |

| Papaya | 1 cup | 116 | 110 |

| Orange juice | 1 cup | 110 | 108 |

| Spring onions | 6 pieces | 92 | 92 |

| Raw rocket | 4 cups | 77.6 | 20 |

| Cooked cauliflower | 1 cup | 55 | 28 |

| Pumpkin flower | 1 cup | 54 | 20 |

| Strawberries | 17 pieces | 49 | 65 |

| Raw celery | 1 1/2 cups | 48.5 | 22 |

| Oranges | 2 pieces | 45.7 | 72 |

| Kiwi | 1 1/2 pieces | 43.3 | 69 |

| Tinned corn on the cob | 1/2 cup | 40 | 66 |

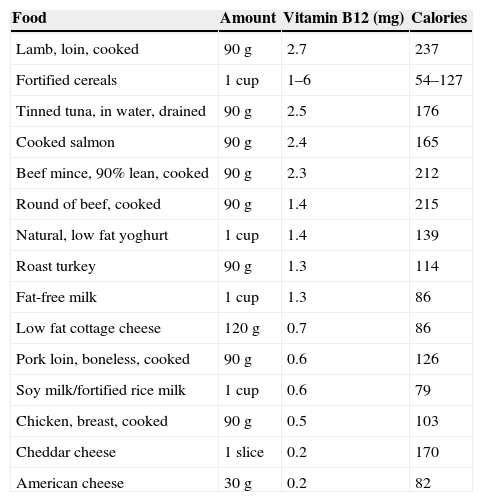

Vitamin B12, together with folic acid, is known to stimulate blood and nerve cell growth. Methylcobalamin, an active form of cobalamin and a co-enzyme in tetrahydrofolate (vitamin B9) metabolism, is essential for thymine synthesis. Cobalamin deficiency, therefore, leads to changes in DNA and RNA synthesis. Extrinsic, or dietary, intake of vitamin B12 must be complemented by the intrinsic factor, which is produced in the stomach. Many individuals over the age of 50, or those with achlorhydria, cannot absorb dietary vitamin B12. In these cases, the use of more fortified foods should be considered. The daily recommended intake of vitamin B12 in adults is 2.4mcg/day, and 2.6mcg/day and 2.8mcg/day in pregnant and breast feeding women, respectively.9,13,14

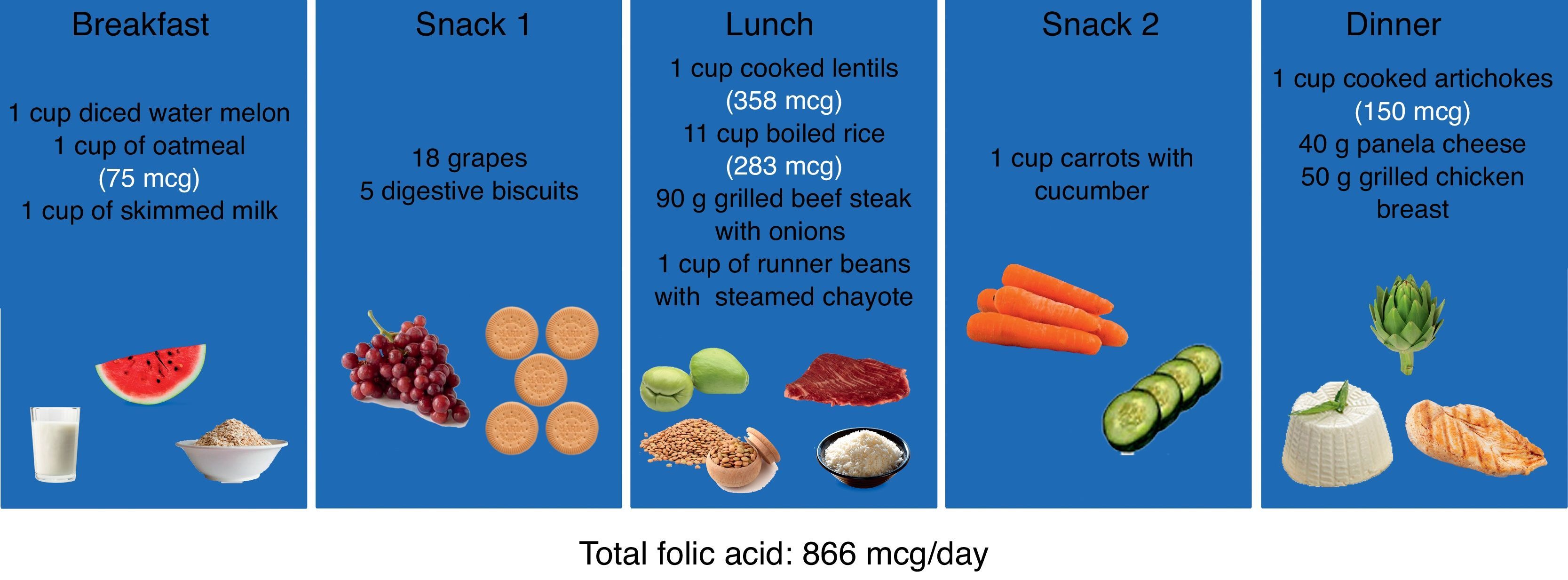

Vitamin B12 does not occur naturally in plant foods; therefore, vegetarians at risk for vitamin B12 deficiency should be closely monitored. Absorption is improved with riboflavin, niacin, magnesium and vitamin B6.9,14Table 3 shows the vitamin B12 content of animal foods and fortified plant foods. Fig. 3 shows a dietary regimen capable of supplementing vitamin B12 deficiency. Note that, contrary to popular belief, large amounts of red meat are not essential in this diet.

Vitamin B12 content of animal and plant foods.

| Food | Amount | Vitamin B12 (mg) | Calories |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lamb, loin, cooked | 90g | 2.7 | 237 |

| Fortified cereals | 1 cup | 1–6 | 54–127 |

| Tinned tuna, in water, drained | 90g | 2.5 | 176 |

| Cooked salmon | 90g | 2.4 | 165 |

| Beef mince, 90% lean, cooked | 90g | 2.3 | 212 |

| Round of beef, cooked | 90g | 1.4 | 215 |

| Natural, low fat yoghurt | 1 cup | 1.4 | 139 |

| Roast turkey | 90 g | 1.3 | 114 |

| Fat-free milk | 1 cup | 1.3 | 86 |

| Low fat cottage cheese | 120g | 0.7 | 86 |

| Pork loin, boneless, cooked | 90g | 0.6 | 126 |

| Soy milk/fortified rice milk | 1 cup | 0.6 | 79 |

| Chicken, breast, cooked | 90g | 0.5 | 103 |

| Cheddar cheese | 1 slice | 0.2 | 170 |

| American cheese | 30g | 0.2 | 82 |

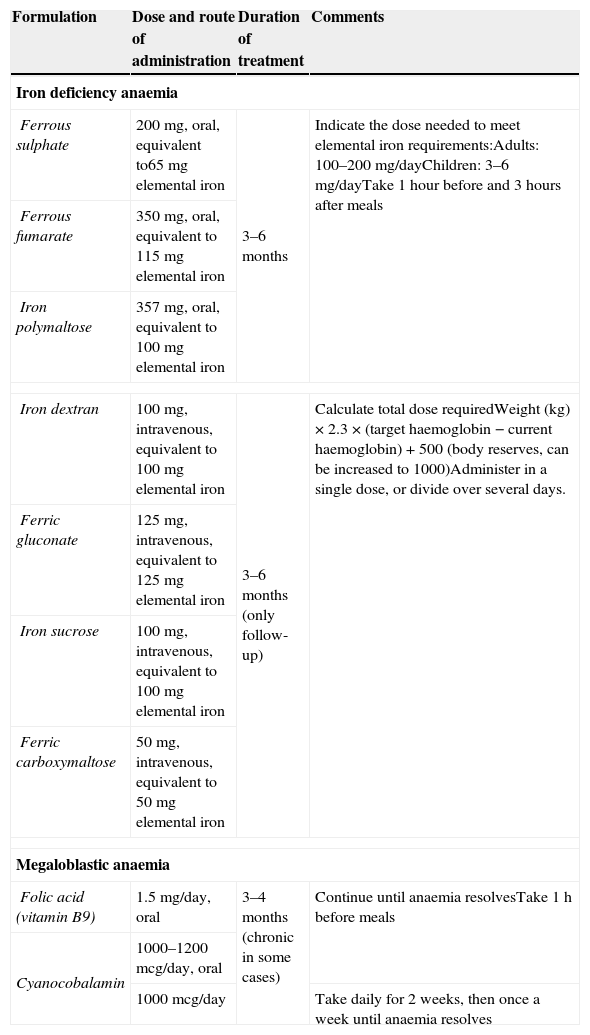

In addition to nutritional recommendations, deficiency anaemia must also be treated pharmacologically with supplements appropriate to each type of anaemia. In patients with iron deficiency anaemia, first line therapy should be oral supplements, with intravenous administration being reserved for patients intolerant of oral supplements, with poor intestinal absorption due to prior surgery, or with cancer-related anaemia. In the case of megaloblastic anaemia, oral therapy should also be considered first, except in patients with pernicious anaemia (atrophic gastritis leading to loss of parietal cells associated with intrinsic factor expression). Table 4 shows a summary of products available for the treatment of anaemia.15–17

Pharmacological management of anaemia.

| Formulation | Dose and route of administration | Duration of treatment | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron deficiency anaemia | |||

| Ferrous sulphate | 200mg, oral, equivalent to65mg elemental iron | 3–6 months | Indicate the dose needed to meet elemental iron requirements:Adults: 100–200mg/dayChildren: 3–6mg/dayTake 1 hour before and 3hours after meals |

| Ferrous fumarate | 350mg, oral, equivalent to 115mg elemental iron | ||

| Iron polymaltose | 357mg, oral, equivalent to 100mg elemental iron | ||

| Iron dextran | 100mg, intravenous, equivalent to 100mg elemental iron | 3–6 months (only follow-up) | Calculate total dose requiredWeight (kg)×2.3×(target haemoglobin−current haemoglobin)+500 (body reserves, can be increased to 1000)Administer in a single dose, or divide over several days. |

| Ferric gluconate | 125mg, intravenous, equivalent to 125mg elemental iron | ||

| Iron sucrose | 100mg, intravenous, equivalent to 100mg elemental iron | ||

| Ferric carboxymaltose | 50mg, intravenous, equivalent to 50mg elemental iron | ||

| Megaloblastic anaemia | |||

| Folic acid (vitamin B9) | 1.5mg/day, oral | 3–4 months (chronic in some cases) | Continue until anaemia resolvesTake 1h before meals |

| Cyanocobalamin | 1000–1200mcg/day, oral | ||

| 1000mcg/day | Take daily for 2 weeks, then once a week until anaemia resolves | ||

Vitamin supplements are currently available in various different presentations and formulations. These, due to regulatory loopholes, are sold over the counter with no guidance on individual dosage requirements or correct administration. Physicians should be aware of this situation, and understand that management of anaemia involves more than pharmaceutical remedies; these, after all, can easily be obtained over the counter by patients, without the need to consult their doctor. This is where the importance of primary and secondary non-pharmacological measures lies. Advising patients on the right diet to complement their pharmacological therapy has many important advantages: (1) It will enable dietary sources to complement supplements to build up body reserves; (2) It will help patients avoid food that interfere with the absorption of dietary iron, and even of prescribed supplements; (3) It will prevent interactions between food and iron supplements that can aggravate adverse effects; (4) It will teach patients about the importance of diet, so that after their therapy they will continue to eat iron- or vitamin B-rich foods and avoid a recurrence of anaemia.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.