Essential thrombocythaemia is a rare pathology in adults and extremely rare in children, making it a diagnostic challenge for paediatricians. The challenge is greater when patients are asymptomatic, despite an incidental discovery of thrombocytosis.

We report the case of extreme thrombocytosis found in an asymptomatic child of 3 years with no personal history or familial history. Study protocol started by ruling out laboratory errors, infectious disease, haemolytic anaemia, iron deficiency anaemia and autoimmune diseases. Bone marrow sample confirmed elevated megakaryocyte production, with other cell lines within normal ranges. Genetic analysis (including JAK2 mutation) was also negative, leading to a differential diagnosis of essential thrombocythaemia. Hydroxyurea (10mg/kg) and aspirin (5mg/kg) were prescribed. A moderate reduction in platelet count was achieved after 4 weeks of treatment.

La trombocitemia esencial es poco frecuente en adultos y extremadamente rara en población pediátrica, convirtiéndose en un reto diagnóstico para los pediatras. El reto es mayor cuando el paciente se encuentra asintomático, a pesar de cursar con una trombocitosis descubierta fortuitamente.

Caso clíniconiño de 3 años de edad, asintomático, cursando con trombocitosis extrema. Sin antecedentes personales o familiares de importancia. Se inició el protocolo de estudio descartando errores de laboratorio, procesos infecciosos, anemia hemolítica, anemia ferropénica y alteraciones autoinmunes. La médula ósea obtenida por aspiración reveló producción aumentada de megacariocitos, sin alteración del resto de líneas celulares. La búsqueda de alteraciones genéticas fue negativa, incluyendo mutación JAK2. El diagnóstico por exclusión fue trombocitemia esencial. Se prescribió hidroxiurea (10mg/kg) y ácido acetilsalicílico (5mg/kg). Posterior a 4 semanas de tratamiento se obtuvo una reducción moderada de la cifra de plaquetas.

Thrombocytosis is generally defined as a platelet count higher than 450×109/L. Mild thrombocytosis is defined as a platelet count of 450–700×109/L; moderate thrombocytosis is a count of 700–900×109/L; and in severe thrombocytosis, platelets are higher than 900×109/L. A platelet count in excess of 1000×109/L is considered extreme thrombocytosis.1,2

Thrombocytosis is a common finding on the complete blood count of children, with a reported prevalence of between 3% and 15%, and a slight preponderance of boys vs. girls. It is often transient, and occurs secondary to various underlying medical, usually inflammatory, disorders. It is more common in young children, either because of the immaturity of their innate and/or adaptive immune systems, or because they are more prone to infections.1,2

Essential thrombocythaemia (ET) is a chronic myeloproliferative disorder characterized by megakaryocyte proliferation. Although the clinical course is benign, is it associated with serious thrombosis and bleeding, in addition to an increased risk for presenting a more serious haematological malignancy.3–5 Prevalence is estimated at 0.09 cases per million children between the ages of 0 and 16 years.3,6 In Mexico, the first report of a case of infantile thrombocythaemia was published by the Children's Hospital in 1995.3

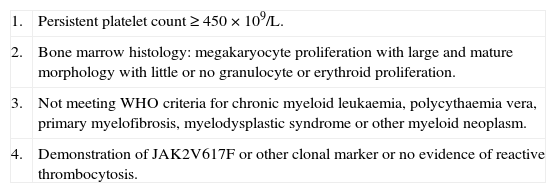

Over half of all cases are asymptomatic, and thrombocytosis is an incidental finding. Symptoms are nonspecific, with headache being the most widely reported. There is a high incidence of serious thrombosis (15%), and moderate-serious (10%) and mild (15%) bleeding. In 2008, the World Health Organization issued revised diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative disorder, establishing 4 major, and no minor, criteria for the diagnosis of ET (Table 1).4,5

Diagnostic criteria for essential thrombocythaemia (World Health Organization, 20084).

| 1. | Persistent platelet count≥450×109/L. |

| 2. | Bone marrow histology: megakaryocyte proliferation with large and mature morphology with little or no granulocyte or erythroid proliferation. |

| 3. | Not meeting WHO criteria for chronic myeloid leukaemia, polycythaemia vera, primary myelofibrosis, myelodysplastic syndrome or other myeloid neoplasm. |

| 4. | Demonstration of JAK2V617F or other clonal marker or no evidence of reactive thrombocytosis. |

The JAK2V617F mutation occurs on the JAK2 gene on chromosome 9 and triggers excessive cell growth not linked to growth factors.4,7 The mutation is present in many patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, particularly polycythaemia vera; in ET, it is found in 23%–57% of adults,7 but according to the review published by Kucine et al., 2014, only 28 mutation have been found in children.2

Treatment guidelines are controversial and involve either hydroxyurea or anagrelide.8

Hydroxyurea is an antimetabolite that selectively inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase, an enzyme required to convert ribonucleoside diphosphates into deoxyribonucleoside diphosphates, a crucial and probably limiting step in DNA synthesis. Hydroxyurea is mainly used to treat selected myeloproliferative disorders.

Anagrelide is an imidazoquinazoline that inhibits megakaryocyte maturation and reduces elevated platelet counts.8

In this study, we report the case of an uncommon clinical presentation in a paediatric patient.

Case reportThe patient was a boy aged 3 years (born in 2011), a resident of Mexico City, with no family history of note. The father and mother were both healthy, aged 38 and 34, respectively.

The patient lives in an urban dwelling, far from industrial areas, power lines and landfill sites. He denies contact with myelotoxic substances, such as pesticides, benzene, ionizing radiation, or heavy metals.

He is the mother's third child following an uneventful pregnancy, weighing 3.150g at birth and measuring 49cm.

Medical historySomatic and functional development. No changes relevant to the current complaint. Immunizations up to date.

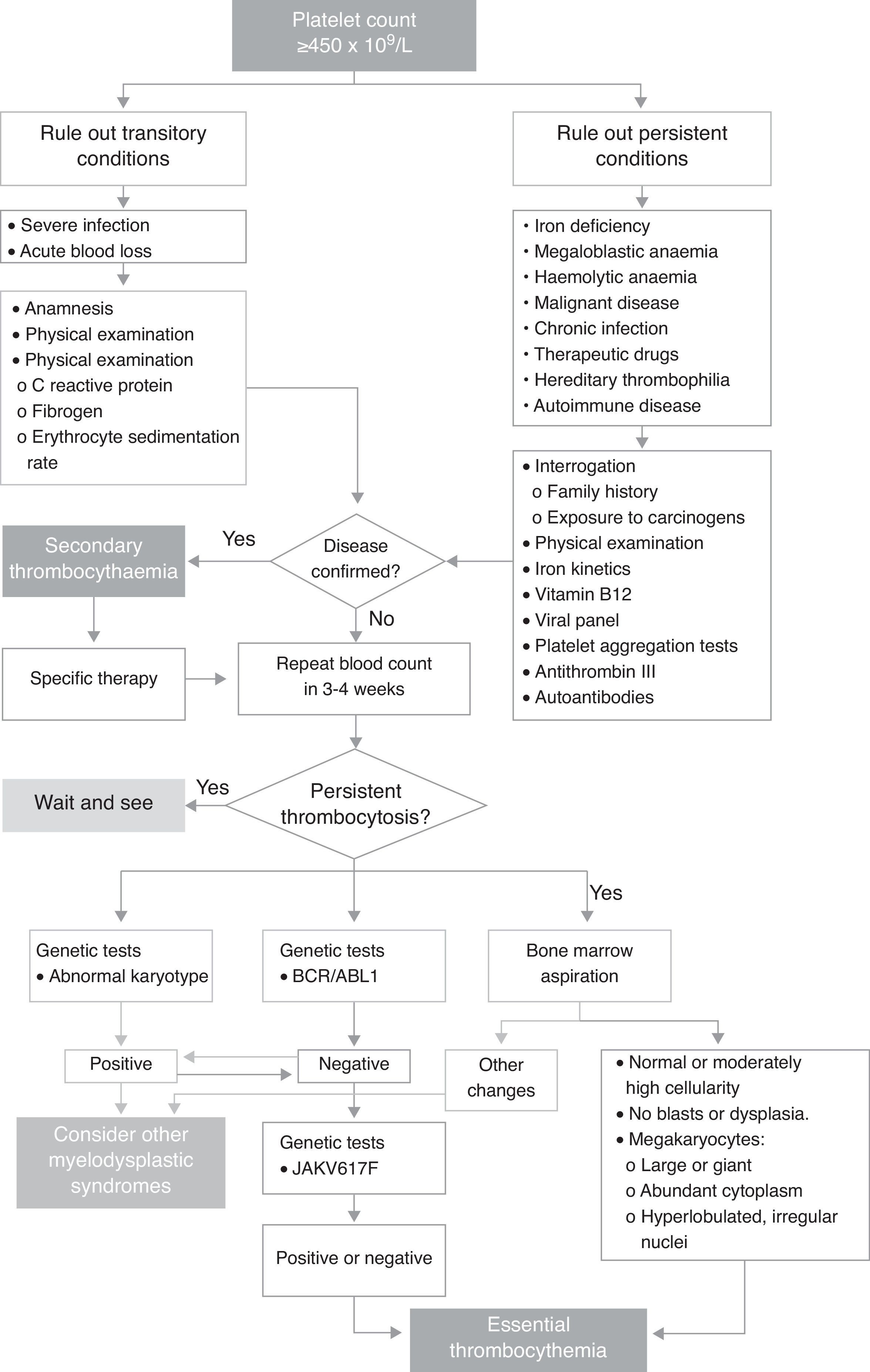

Current complaintAsymptomatic patient referred to Paediatric Haematology following extreme thrombocytosis of 1,492,000×109/L found during blood tests performed on 25 February 2014. The blood count was part of the preoperative workup for circumcision and right side orchidopexy. The protocol for childhood thrombocytosis, shown in Fig. 1, is started.

Physical examinationWell developed male patient, conscious and oriented, active, reactive, with no pallor, pupils equal and reactive to light, oral mucosa moist. No mucosal lesions, no evidence of adenopathy, lung fields are clear and well-ventilated, heart has regular rate and rhythm, no murmurs, abdomen soft, depressible and non-tender, no hepatosplenomegaly, normal peristaltic sounds, no masses, well-developed genitals, full range of motion in extremities, with no oedema or evidence of venous or arterial problems.

Clinical courseThe boy was seen again in April with the results of the test (Fig. 1) performed to rule out other diseases. The findings of a new whole blood count showed a platelet count of 971,000. The interview and physical examination were both compatible with viral influenza associated with thrombocytosis, and the patient was given symptomatic treatment.

At the following appointment, on September 3, 2014, the platelet count was 3,153,000, and the patient was totally asymptomatic. Therefore, after ruling out other underlying conditions that could be causing the thrombocytosis, we suspected essential thrombocythaemia, and ordered bone marrow aspiration and specific molecular testing. The findings of these tests met the diagnostic criteria for ET, and the diagnosis was therefore confirmed (Table 1).

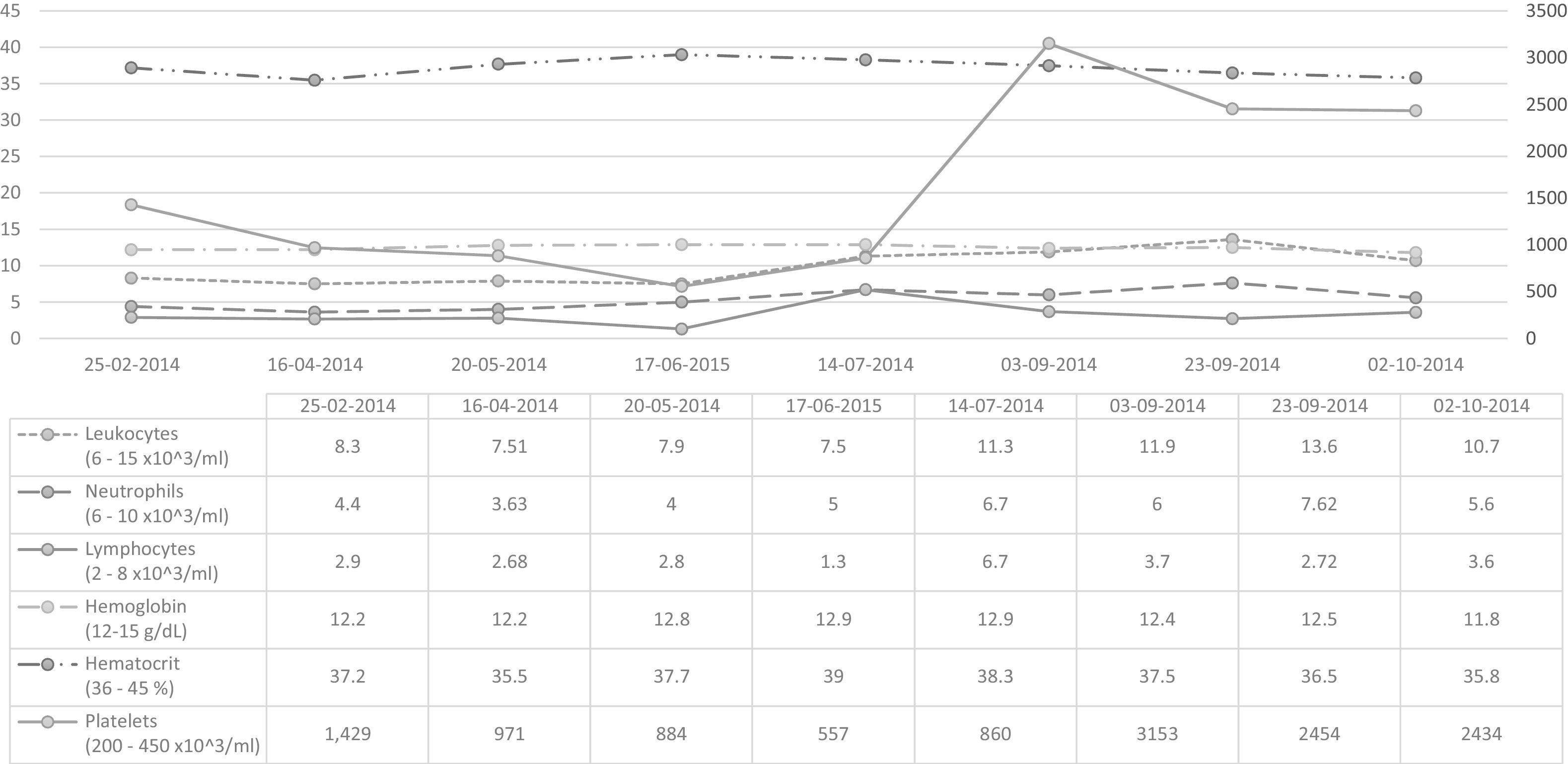

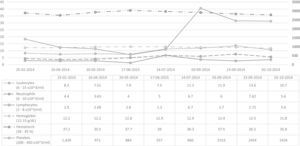

Laboratory and molecular biology studiesFig. 2 shows the changes in blood chemistry.

Iron metabolism parameters in the normal range. Serology negative for infection.

Vitamin B12 quantification: 520pg/ml (reference range: 200–900pg/ml) and functional antithrombin III 118% (reference range: 80–120%).

Molecular biology studies: Normal karyotype (46 XY). BCR/ABL1 Negative (19/09/2014). JAKV617F not mutated (23/09/2014).

Clinical and invasive studiesAn abdominal ultrasound performed in September 2014 was unremarkable, with a normal spleen (9cm greatest diameter).

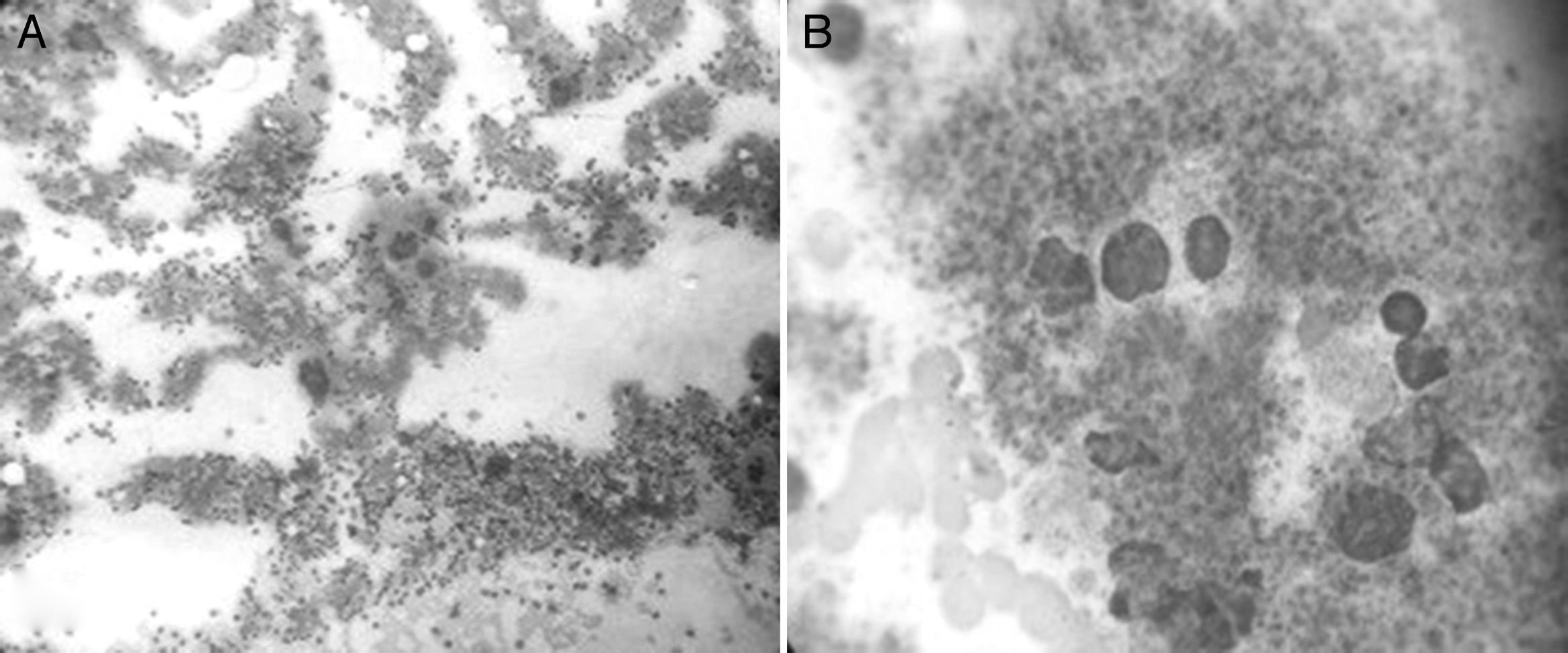

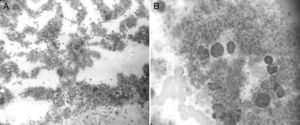

On September 10, 2014, bone marrow aspiration was performed, showing normocellular bone marrow with abundant, greatly enlarged megakaryocytes forming platelet clumps with abundant cytoplasm and irregular, hyperlobulated nuclei; architecture is otherwise preserved, with a slight increase in eosinophils (Fig. 3).

Photomicrograph of bone marrow aspirate obtained from the sternum, magnified 400× (A) and 1800× (B). It shows normocellular bone marrow with abundant, greatly enlarged megakaryocytes with abundant cytoplasm and irregular nuclei. Architecture is otherwise preserved, with a slight increase in eosinophils.

The patient was started on 10mg/kg hydroxyurea and 5mg/kg acetylsalicylic acid on September 4; 4-week follow-up showed a moderate reduction in platelet count.

DiscussionIn paediatric patients, an incidental finding of thrombocytosis should be confirmed with an additional blood count, as some clinical situations can cause a false high platelet count (mixed cryoglobulinaemia or lysis). The primary aim should be to stabilize the patient, and then follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 1 to confirm a diagnosis of secondary or clonal thrombocytosis.9 These studies are performed in sequence to rule out the main underlying causes of secondary thrombocytosis. They include tests for infection, iron deficiency anaemia, haemolytic anaemia, and autoimmune disease.6,10 Although platelet clumping tests were not performed in this case, they can give valuable insight into platelet function. Primarily, they provide a clearer picture of the risk of presenting thrombotic complications from platelet activation. In addition, reports have shown that in patients with very high platelet levels, the likelihood of haemorrhage paradoxically increases as a result of the increased proteolysis of large vWF multimers.7,11

It is important to evaluate the family history of thrombocytosis, as this can suggest hereditary thrombocytosis. Some studies have reported families with thrombocytosis-causing mutation isolated in the thrombocytopenia gene, the TPO CMPL receptor gene (MPL), and more recently, JAK2.

The final step involves bone marrow aspiration, which shows the presence of megakaryocyte proliferation, with an increase in the number of mature enlarged megakaryocytes and no significant increase or shift to the left of neutrophil granulopoiesis or of erythropoiesis.12

The presence of the BCR-ABL fusion gene rules out essential thrombocythaemia. Samples must be tested for the JAK2V617F mutation (positive in 40%–50% of all cases) or MPLW5151K/L (1% of all cases).13,14 A finding of JAK2V617F mutation in addition to the foregoing bone marrow findings contributes to the diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasm.

The prevalence of essential thrombocythaemia is around 60 times greater in adults than in children. The JAK2V617F mutation is also less common in children, making pathogenesis and diagnostic techniques in children a considerable challenge.1 In the case presented here, the patient met all the diagnostic criteria for ET (Table 1), because despite the absence of the JAK2V617F mutation, any other origin of thrombocytosis was ruled out following the recommendations of the latest WHO guidelines. It is also important to bear in mind that although JAK2V617F is the most common mutation, another mutation occurring within exon 12 of the JAK2 gene has a similar effect as JAK2V617F. The mutation, however, has primarily been reported in other myeloproliferative neoplasms, such as polycythaemia vera.15

There are 2 main therapeutic options in the management of patients with ET: (A) Antiplatelets (acetylsalicylic acid), usually used in a conservative “wait and see” context; (B) Cytoreductive therapy. The latter is reserved for cases of severe ET, in other words, in patients aged 60 years or older with other comorbidities or thrombotic and/or bleeding complications, or when the platelet count exceeds 1500×109/L, as was the case with our patient.2,5

Although some cytoreductive therapies in children have been reported, the lack of evidence has prevented any clear consensus on the correct approach. This is why the main sources for such treatment consist of case reviews reporting the successful use of hydroxyurea, with anagrelide and interferon being considered second line treatment in high risk patients that either do not tolerate or do not respond to hydroxyurea. Some authors have recently pointed to interferon alpha as the treatment of choice, based on its excellent safety profile even in pregnant women, and because it does not increase the already considerable risk of leukaemia.16,17 Although Giona et al., in a retrospective analysis of the 3 available cytoreductive drugs, chose interferon over other remedies, they recommend evaluating therapy on a case-by-case basis, and ultimately consider all 3 agents to be equally effective.5,17 Experience in the use of anagrelide is limited, and it is relegated to second line therapy.16,18 On this basis, and in consideration of the high cost of other options, we chose to treat our patient with hydroxyurea. This therapy has the added advantage of oral administration, in contrast to interferon alpha, which must be administered by trained staff.

ConclusionEssential thrombocythaemia is an uncommon disorder in children. For diagnostic purposes, it is of vital importance to differentiate between essential thrombocythaemia and secondary thrombocytosis; a negative JAK2 mutation test does not necessarily rule out the diagnosis, and treatment should be started in symptomatic patients, or in those at high risk for complications.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.