During 2003, 2007, 2008 and 2010, bat assemblages were studied at different dry valleys in Guatemala. Ten individuals of Choeronycteris mexicana (7 females and 3 males) were captured almost exclusively during the dry season. Pollen of columnar cacti (Stenocereus pruinosus and Pilosocereus leucocephalus) and Ceiba aesculifolia were found in samples recovered from hair. Remains of insects were recovered from feces samples of one individual. Reproductive females and a juvenile were captured between March and June of the different years. The captures coincided with the blooming of columnar cacti flowers, and with the presence of Leptonycteris yerbabuenae. Our data suggest that C. mexicana is a seasonal visitant at sub-humid biological corridor in Guatemala.

Durante 2003, 2007, 2008 y 2010 se estudió el ensamble de murciélagos en distintos valles secos en Guatemala. Se capturaron 10 individuos de Choeronycteris mexicana (7 hembras y 3 machos) casi exclusivamente durante la estación seca. En muestras recuperadas del pelo se encontró polen de cactus columnares (Stenocereus pruinosus y Pilosocereus leucocephalus) y Ceiba aesculifolia. Asimismo, se recuperaron restos de insectos en muestras de heces de un individuo. Se capturaron hembras reproductivas y un juvenil entre los meses de marzo y junio de los diferentes años. Las capturas coincidieron con la floración de los cactus columnares y con la presencia de Leptonycteris yerbabuenae. Nuestros datos sugieren que Choeronycteris mexicana es una especie visitante en el corredor biológico subhúmedo de Guatemala.

Choeronycteris mexicana (Tschudi, 1844) is a nectarivorous bat that belongs to the sub-family Glossophaginae (Phyllostomidae). Some morphological features of this species, such as its elongated rostrum and its large size (forearm 43.2–47.8mm and weight 10–20g, Arroyo-Cabrales, Hollander, & Knox, 1987) have been suggested as adaptations to feed on columnar cacti flowers, and it is also presumed to move great distances (Simmons & Wetterer, 2002). This bat species is uncommon to rare along its distribution range, which extends from the south of the United States to Guatemala and Honduras (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987; Cryan & Bogan, 2003).

C. mexicana inhabits different ecosystems of low humidity such as deciduous, semi-arid and pine-oak forests (Cryan & Bogan, 2003; Fleming, Nuñez, & da Silveira, 1993; Peñalba, Molina, & Larios, 2006; Riechers-Pérez & Vidal-López, 2009), where they play an important role as pollinators of a great variety of plants mainly of the genus Agave, and different species of columnar cacti (Peñalba et al., 2006; Valiente-Banuet, Del Coro-Arizmendi, Rojas-Martínez, & Domínguez-Canseco, 1996). Information about its reproduction is scarce, but pregnant females and breeding have been documented between June and September in Arizona and New Mexico in the USA (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987; Cryan & Bogan, 2003). Females give birth to a single litter, although in Guatemala a female was reported carrying 2 embryos (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987).

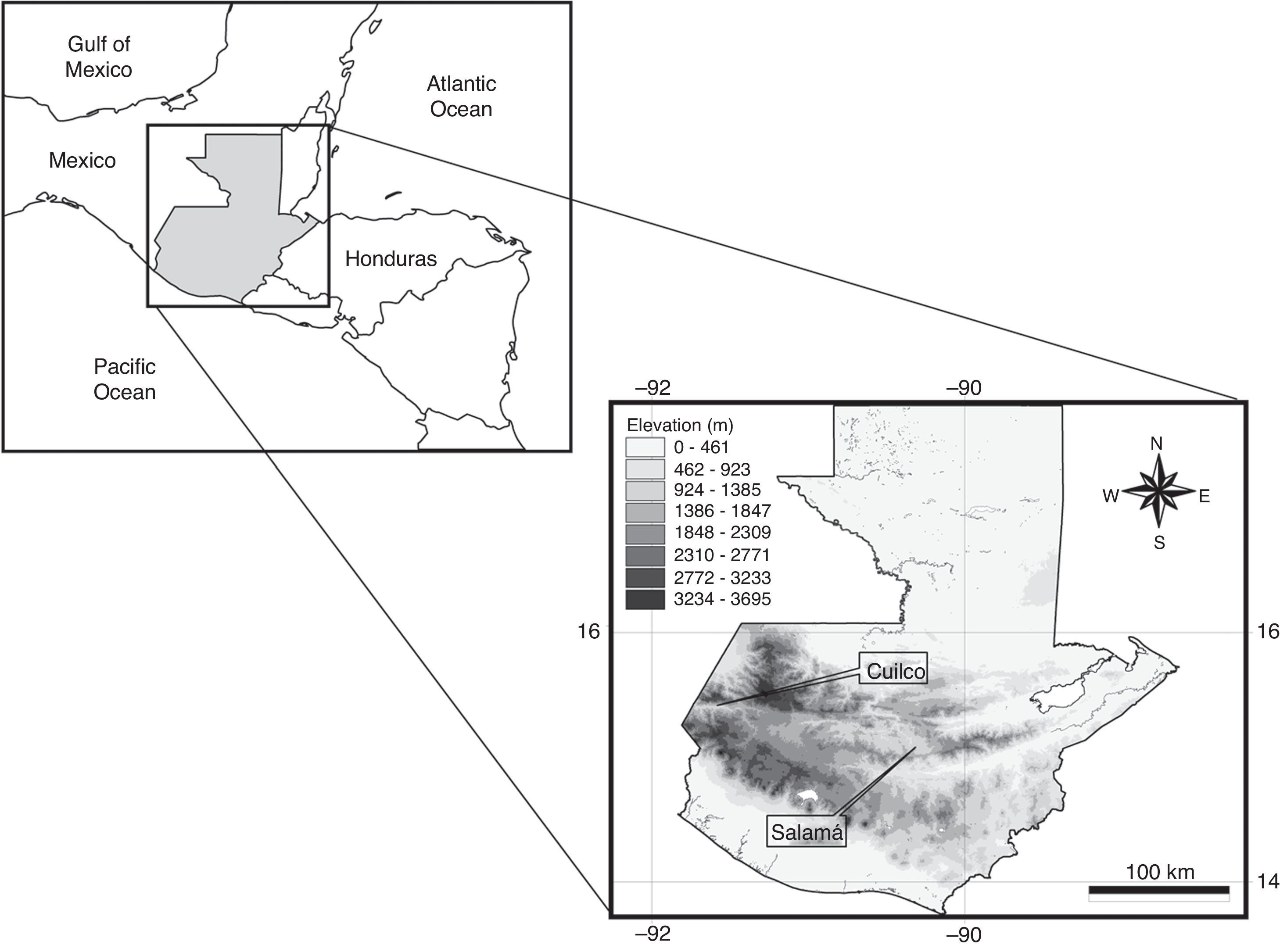

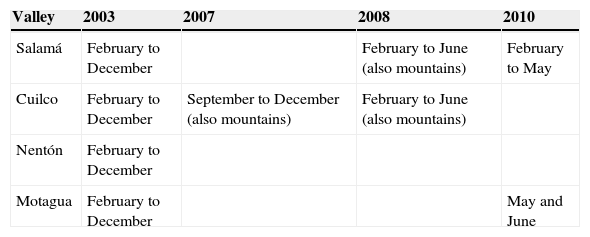

During 2003, 2007, 2008 and 2010, we conducted bat surveys along different enclaves and mountains surrounding them (Table 1) along the sub-humid biological corridor in Guatemala (Stuart, 1954). Bats were captured using mist nets and were identified in the field (Medellín, Arita, & Sánchez, 1997). Pollen was recovered from the hair of captured nectarivorous bats using jelly cubes and was identified with an optical microscope comparing the pollen obtained from the bats with pollen obtained from plants collected around our sampling points, and obtained from herbarium specimens (Herbarium BIGU and USCG, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala).

Bat samplings in different valleys along the sub-humid corridor of Guatemala.

| Valley | 2003 | 2007 | 2008 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salamá | February to December | February to June (also mountains) | February to May | |

| Cuilco | February to December | September to December (also mountains) | February to June (also mountains) | |

| Nentón | February to December | |||

| Motagua | February to December | May and June |

A total of 507 individuals belonging to 8 nectarivorous bat species were captured during the samplings, 82% corresponded to 2 species: Leptonycteris yerbabuenae and Glossophaga soricina. 10 individuals corresponded to C. mexicana, and were captured in 2 locations: the village Sosí Chiquito in Cuilco Valley (15°24′21″N, −91°57′49″W, 1,103m, Fig. 1) and the Regional Park Los Cerritos in Salamá Valley (15°05′06″ N, −90°18′11″ W, 1,080m, Fig. 1); 9 individuals were captured during the dry season.

Pollen was recovered from 5 individuals (sampled from 2003 and 2008). The pollen of columnar cacti and Ceiba aesculifolia were observed in samples of 4 individuals. Pollen of cacti was undifferentiable by microscopy but bats were observed visiting Stenocereus pruinosus and Pilosocereus leucocephalus. Pollen of Inga sp., Crescentia sp., an unknown species of Caesalpinaceae (probably Bahuinia sp.), one of Sapotaceae, one of Asteraceae, and an unidentified species were also found in the samples. The individuals captured in 2010 also carried pollen in their hair presumably of columnar cacti flowers, because the sampling site was located inside a patch of blooming individuals. No seeds were recovered from the bat feces, but remains of insects were recovered from a male captured on December 2003 in Cuilco Valley, when floral resources were scarce.

Of the 10 individuals of C. mexicana captured, 7 females (all adults) and 3 males (one juvenile) were registered. Pregnant females were captured in March (2010) and June (2008). Post lactating females were registered in March (2003), April (2010) and May (2003). Due to manipulation, the pregnant female captured in March 2010 aborted an embryo almost ready to be born (female 6g, forearm 22.3mm).

A post-lactating female and a juvenile male were captured on April 2010; both were captured at the same time and were found separated approximately 30cm in the mist net; probably corresponded to a mother and her offspring. Presumably, this young male was born between 4 or 6 weeks before the capture event, which is the time required to learn to fly by the young (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987; Cryan & Bogan, 2003).

The reports of C. mexicana for Guatemala herein, are the first after 60 years (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987). Several surveys have been carried out in the country during past and recent decades (e.g. Dickerman, Koopman, & Seymour, 1981; Dolan & Carter, 1979; Kraker-Castañeda & Pérez-Consuegra, 2010; MacCarthy, Davis, Hill, Knox-Jones Jr., & Cruz, 1993; Schulze, Seavy, & Whitacre, 2000), but this species has been registered exclusively in 2 sites of the Stuart's sub-humid corridor. The captures coincided with L. yerbabuenae presence and with the occurrence and blooming season of columnar cacti flowers in Guatemala (Arias & Véliz, 2006).

We found that in the Guatemalan dry valleys, the columnar cacti are key resources for C. mexicana as has been reported in other regions along its distribution range (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987; Coro-Arizmendi, Valiente-Banuet, Rojas-Martínez, & Dávila-Aranda, 2002; Simmons & Wetterer, 2002). Fleming et al. (1993), reported that migratory populations of L. yerbabuenae and C. mexicana are dependent of columnar cacti, compared with resident populations of both species. Riechers-Pérez and Vidal-López (2009) studied bats around the central depression of Chiapas, southeast Mexico, during 2 consecutive years at different altitudes; they captured C. mexicana between April and August. The months in which this species was captured in Chiapas coincide with our observations and they point out that C. mexicana is a seasonal visitor in the southern portion of its distribution (at least in the Guatemalan inter-mountain dry valleys). To date, there is not enough information to clarify where these bats come from, and how large are the distances they travel from Mexico to the Guatemalan dry forests.

It has been proposed that the dry valleys of central Mexico produce enough resources to maintain year round resident populations of L. yerbabuenae and C. mexicana (Rojas-Martínez, Valiente-Banuet, Del Coro-Arizmendi, Alcantara-Eguren, & Arita, 1999), in contrast to the northern limits of their distribution, where at least some groups move to the south (Fleming et al., 1993; Peñalba et al., 2006).

As already mentioned, C. mexicana was captured almost exclusively during the dry season, the time when the columnar cacti flowers of S. pruinosus and P. leucocephalus bloom. Fruits of columnar cacti can be found from April to June (unpublished data), but from June to December the floral resources are scarce for nectarivorous bats in the inter-mountain dry valleys of Guatemala. The abundance of resources during the dry season, and the scarcity during the wet season, could be the explanation of the seasonal pattern of this bat species in Guatemala.

The available information and the data presented here suggest that males and females segregate during the time of gestation and parturition. In New México, USA, Couoh et al. (2006) found changes in the sex ratio during the months of parturitions and lactation, and reported ratios of approximately 1:1, but they captured only females from October to December. Cryan and Bogan (2003) also reported that in Arizona, the majority of historical reports are females and young individuals. In Chiapas, Mexico, the males–females ratio was of 1.5:1, but no reproductive evidence was found (Riechers-Pérez & Vidal-López, 2009).

In Salamá Valley, we found a sex ratio of 0.3:1, and 5 of 7 females presented reproductive evidence, supporting the hypothesis of segregation during reproduction periods. In addition, our data provide evidence of a bimodal reproduction pattern in this species, one through June to September reported from central Mexico to the north (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 1987), and a second one approximately from March to June in Salamá Valley; due to the abundance of resources and the proximity between valleys, perhaps the Motagua Valley (approximately 40km southeast) is also important for the reproduction of this species.

Our results show that C. mexicana is a seasonal visitor in the dry valleys of Guatemala during the dry season, where they feed mainly from columnar cacti flowers and other plants that present syndrome of chiropterophily. The data also indicate that Los Cerritos Regional Park, in Salamá Valley, is an important area for the reproduction of this species. Due to these facts, it is of a great importance to begin strategies of conservation along the Guatemalan sub-humid corridor in order to protect and recover areas for the maintenance of plant species that are important resources for these species of bats.

We would like to thank the Dirección General de Investigación-Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (Project 32-2003), Fondo Nacional para la Ciencia y la Tecnología (Fodecyt, Project Fodecyt 34-2007). In addition, we are grateful to Escuela de Biología de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas, Fundación para la Defensa del Medio Ambiente en Baja Verapaz, and the cultural group “Sábados culturales”. Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas of Guatemala granted permits to make possible this research. We deeply thank to the people who helped us in the field, the families that housed us in all the villages and to Claudia Romero and Scarlette Cano for comments that helped to improve this manuscript.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.