A series of crater lakes exist in the central region of Puebla, Mexico; each one with an endemic species of silverside fishes, with no information about their ecology. Poblana letholepis is an endemic species to the Crater Lake La Preciosa and under human and physical pressure endangering its presence. The weight–length relationship of both sexes and juveniles were not statistically different, and their feeding habits are similar between sexes and juveniles as well as to other species of the same family.

Existe una serie de lagos dentro de cráteres en la zona central de Puebla, México; cada uno de estos presenta una especie endémica de charales plateados sin información acerca de su ecología. Poblana letholepis es una especie endémica del lago La Preciosa y está bajo presión humana y física, poniendo en peligro su existencia. La relación peso/longitud de los sexos y juveniles no presentaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Los hábitos alimenticios entre sexos y los juveniles no presentan diferencias y son similares a otras especies de la misma familia.

In the central state of Puebla, Mexico, there is a series of crater lakes, which are part of the Libres-Oriental watershed. These lakes are inhabited by several fish species of the Atherinospinae and Menidiinae sub-families, many of them endemic to each of the crater lakes. Poblana letholepis is an endemic silverside fish of the Crater Lake La Preciosa (Miller, Minckley, & Norris, 2005). The population has been under pressure due to overfishing and reduction of the water level to the point that the Mexican Government has declared the species as endangered (Lyons, González-Hernández, Soto-Galera, & Guzmán-Arroyo, 1998; Semarnat, 2010). However, few studies on their biology or ecology have been published (Díaz-Pardo, 1992, 1993). Other topics have been studied in the crater lake La Preciosa such as those on systematics and biogeography of the Menidiini Tribe (Bloom, Piller, Lyons, Mercado-Silva, & Medina-Nava, 2009), physical and chemical characteristics of the lake (Caballero, Vilaclara, Rodríguez, & Juárez, 2003), and a list and ecology of oligochaetes in the lake's shore (Peralta, Escobar, Alcocer, & Lugo, 2002).

Due to lack of information on the ecology of P. letholepis, being an endemic and endangered species, the aim of the present work was to obtain data describing its weight–length relationship as well as its feeding habits during one season.

The Crater Lake La Preciosa is located at 19°24'N, 97°24'W, at 2,224masl in the central part of the state of Puebla, Mexico, with a maximum depth of 64m (Peralta et al., 2002). As part of a survey of various crater lakes project the organisms were caught over 2 nights in December 2012, using a lamp to attract them in the manner of local fishermen. Further visits to the location produced no fish; fishermen commented that the amount of fish has diminished considerably. Once caught, each organism was weighed and its standard length measured, after which it was stored in a 4% formaldehyde solution and taken to the laboratory. Each organism was dissected and its sex determined. The stomach content was analyzed and the food items separated and identified to the maximum taxonomic level possible. In order to determine if statistical differences were present for the length between sexes and between sexes and juveniles, a Student t-test was performed for every pair of data sets. In the case where the t-test assumptions failed, a Mann–Whitney Rank test was performed.

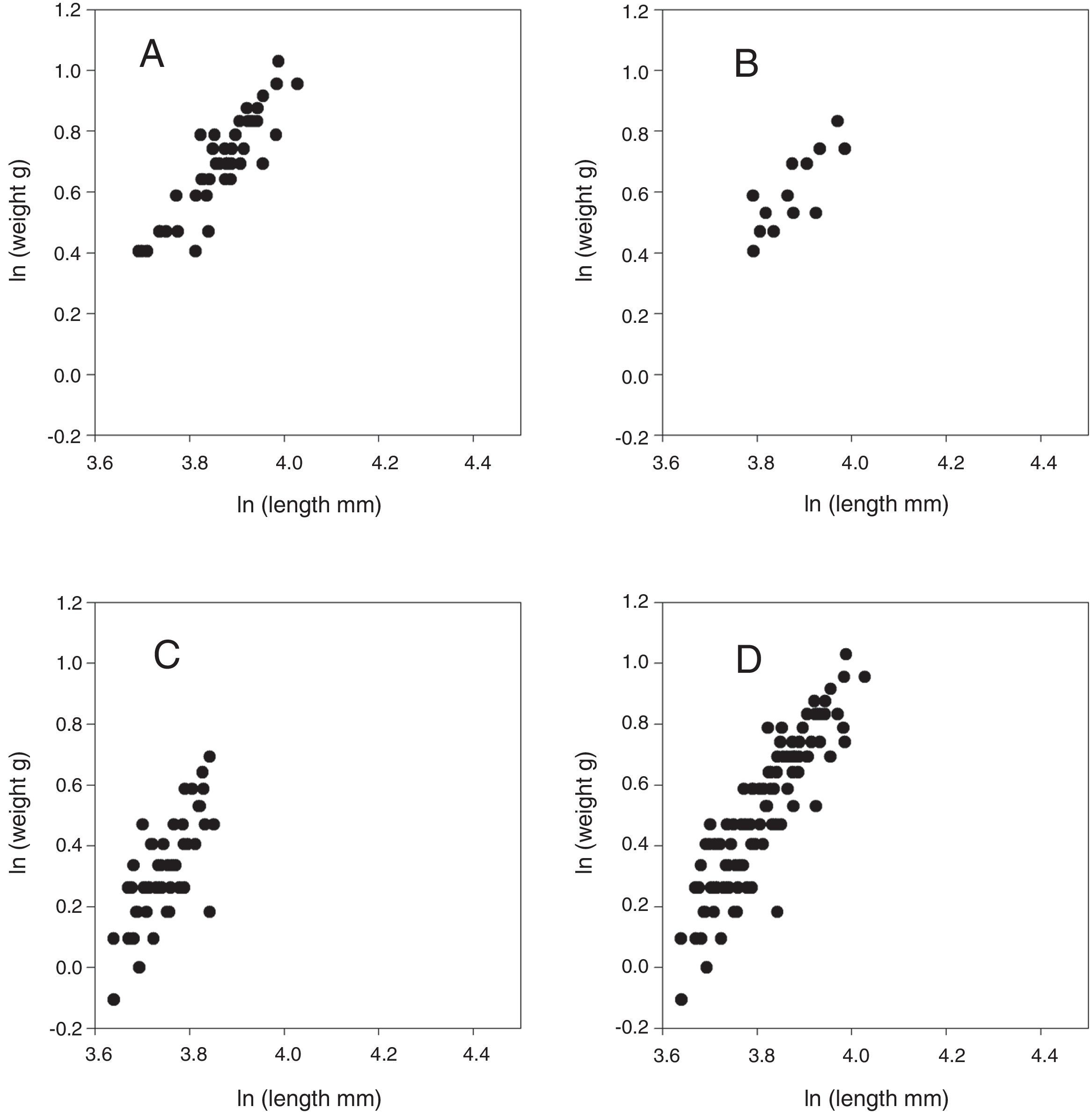

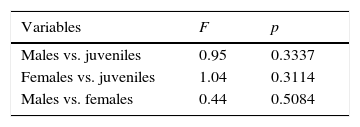

After log transforming the weight and length data for all organisms, the data was divided by sex and juveniles. A minimum square regression analysis was performed for each sex data, the juveniles, and all individuals pooled in order to obtain the weight–length relation, W=aLb, where W is the weight, L the length and a and b constants. After the results were obtained a covariance analysis (Ancova) was performed in order to determine if there were significant differences between the slope (b) constants between sexes and sexes and juveniles.

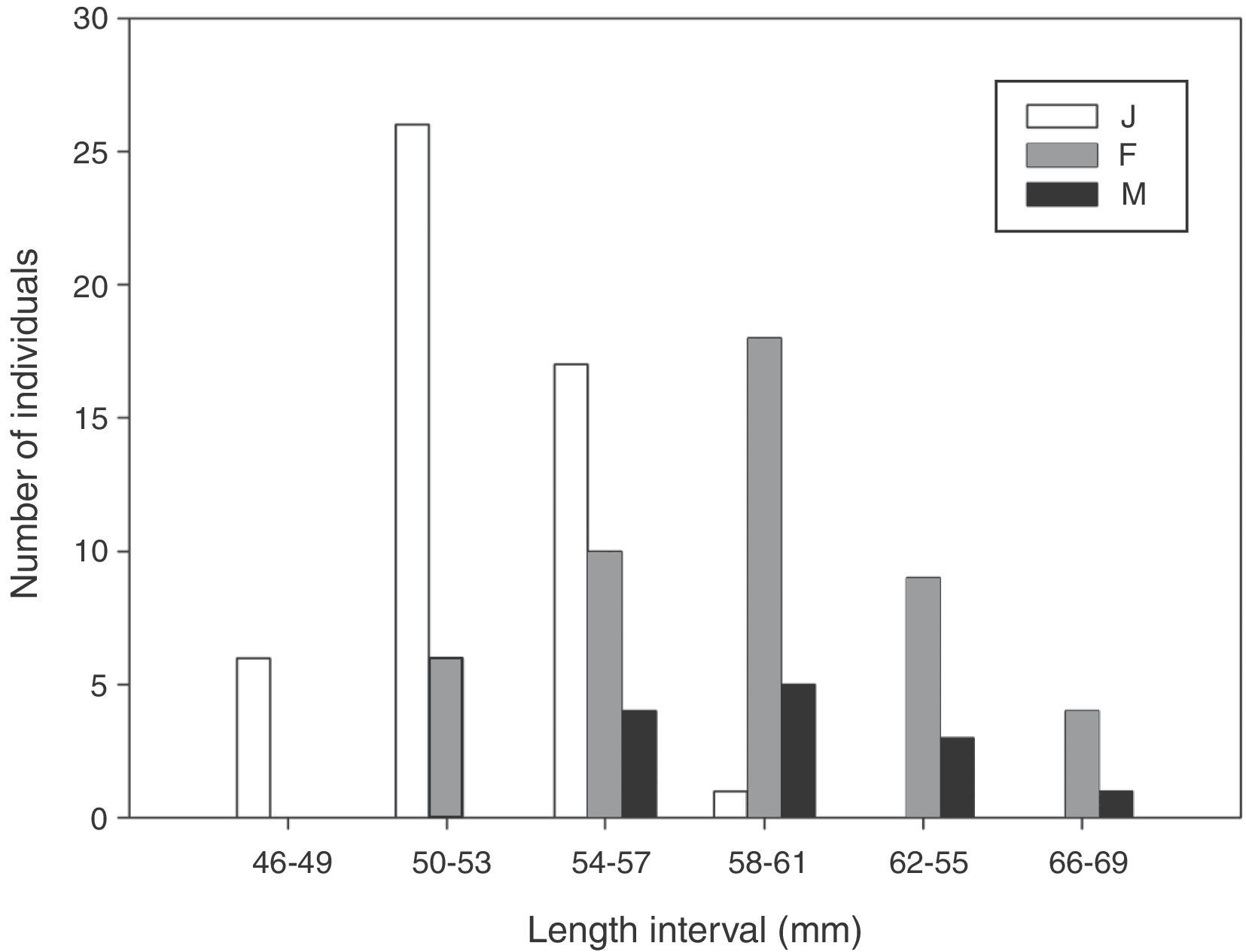

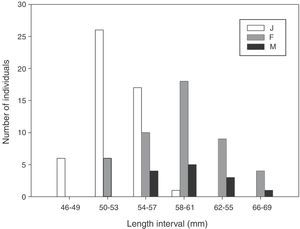

A total of 110 organisms were collected. Of these, 50 were identified as juveniles or immature, 13 as males, and 47 as females. The length range of all individuals spanned from 38.05mm to 56.11mm. Using a 3mm interval, the juveniles’ higher frequency was at the 50–53mm class, with a mean length of 52mm (Fig. 1). For females, the higher frequency was between 58–61mm with a mean length of 58mm. In the case of males, the highest frequency was at the 58–61mm interval with a mean length of 60mm. A Student t-test resulted in a no statistical difference between the mean length value of female and male individuals (t=−0.344; p=0.733) (Table 1). In the case of female and juvenile mean length, a Mann–Whitney Rank test was performed because the Student t-test assumptions failed. Based on this test, there were significant differences between the median of both data sets (U=273.5; p<0.001). For the male and juvenile mean length values, the Student t-test resulted in a significant difference (t=7.293; p<0.001). Considering the weight, the mean value for juveniles was 1.45g, for females 2.0g and for males 1.8g.

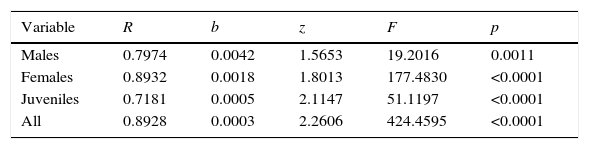

Regression analysis of the log of weight vs. log of length for males, females, juveniles and all pooled of Poblana letholepis of the Crater Lake La Preciosa, Puebla, Mexico.

| Variable | R | b | z | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 0.7974 | 0.0042 | 1.5653 | 19.2016 | 0.0011 |

| Females | 0.8932 | 0.0018 | 1.8013 | 177.4830 | <0.0001 |

| Juveniles | 0.7181 | 0.0005 | 2.1147 | 51.1197 | <0.0001 |

| All | 0.8928 | 0.0003 | 2.2606 | 424.4595 | <0.0001 |

The weight–length relationship was seen to be statistically significant for both sexes, juveniles and the whole set of individuals (Fig. 2, Table 2). The highest value for the constant b was obtained for the all individuals data set (b=2.2606) while the smallest was for the males data set with b=1.5653. The Ancova resulted in no statistical differences between any of the b constant values for any of the data sets, that is, there were no differences in the growth rate of females, males, juveniles or all individuals pooled (Table 3).

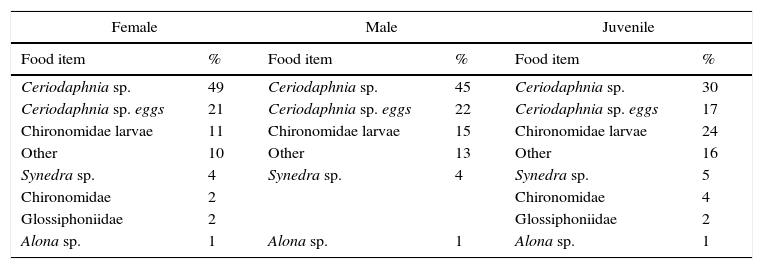

Food items for females, males and juveniles of Poblana letholepis of the Crater Lake La Preciosa, Puebla, Mexico.

| Female | Male | Juvenile | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food item | % | Food item | % | Food item | % |

| Ceriodaphnia sp. | 49 | Ceriodaphnia sp. | 45 | Ceriodaphnia sp. | 30 |

| Ceriodaphnia sp. eggs | 21 | Ceriodaphnia sp. eggs | 22 | Ceriodaphnia sp. eggs | 17 |

| Chironomidae larvae | 11 | Chironomidae larvae | 15 | Chironomidae larvae | 24 |

| Other | 10 | Other | 13 | Other | 16 |

| Synedra sp. | 4 | Synedra sp. | 4 | Synedra sp. | 5 |

| Chironomidae | 2 | Chironomidae | 4 | ||

| Glossiphoniidae | 2 | Glossiphoniidae | 2 | ||

| Alona sp. | 1 | Alona sp. | 1 | Alona sp. | 1 |

For all fish collected, the zooplankton items (Cladocera: Alona sp, Cariodaphnia sp, and Ceriodaphnia eggs) were 77% of all food items. Insects (Chironomidae and their larvae) were 3%, diatoms (like Symedra sp) were 4%, Hirudinea (Glossiphomiidae) 2%, and other items not identified 14%. In the case of sexes and juveniles, there were no differences in food items between the individuals, as noted in Table 3. With just slight differences, the proportions eaten by the individuals are similar independent of the sex or if they are juveniles.

The growth parameter b was just below the limits published by Froese (2006) of 2.5–3.5. The diet composition of this species is common for a small pelagic fish and reflects the high supply of Cladocera in the lake. Compared with other species of the Atherinopsidae family also endemic to Mexico, there are no differences in the diet items. Elías, Navarrete-Salgado, and Rodríguez (2008), Navarrete-Salgado, Hernández, and Elías (2006), García-de-León, Ramírez-Herrejón, García-Ortega, and Hendrickson (2014), and Ramírez-Herrejón et al. (2014) report a high preference for cladocerans, and copepods as the main food items, with insects as a secondary preference. Considering that P. letholepis is endemic to La Preciosa crater lake, this report is a step towards the knowledge of its ecology and future management.

We appreciate the comments of two reviewers which enriched the manuscript. Thanks to Patricia “Trisha” Vargas for the English review.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.