Little is known of wood-inhabiting aphyllophoroid fungi in some Mexican territories. The State of Aguascalientes is an example: there have been few records of these fungi until now. The main objective of this study is to provide a preliminary inventory of the wood-inhabiting aphyllophoroid species of the state. The fieldwork was carried out by sampling the principal plant communities during the main period of basidiomata production in 2011. A preliminary list of 81 species is presented, 55 of these recorded for the first time in the state. Additionally, a non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was conducted to explore the fungal communities. Based on the vegetation, 3 significantly differentiated aphyllophoroid community groups were identified: temperate forests, scrublands and deciduous tropical forest. The highest species richness was found in oak forests.

Los hongos afiloforoides lignícolas están poco estudiados en algunos territorios de México. El estado de Aguascalientes es un ejemplo de ello, ya que hasta ahora poseía escasas citas de estos hongos. El objetivo principal de este trabajo fue hacer un inventario preliminar de hongos afiloforoides lignícolas para el territorio. Para ello se muestrearon varios tipos de comunidades vegetales durante el periodo óptimo para la producción de basidiomas de los hongos en 2011. Se presenta una lista de 81 especies, de las cuales 55 son nuevas citas para el estado. Para analizar la comunidad fúngica con base en la vegetación, se aplicó el método de análisis de escalamiento multidimensional no métrico (MDS) con el que se formaron 3 grupos significativos: los bosques templados, los matorrales y la selva baja caducifolia. Asimismo, cabe señalar que el bosque de encino fue la comunidad vegetal con mayor riqueza en especies estudiadas.

The few studies that exist for wood-inhabiting fungi in Mexico are quite recent. Interest in studying these organisms has recently increased, as wood-inhabiting fungi are an ecologically important and highly diverse group (Stokland et al., 2012). Furthermore, the wide variety of landscapes in Mexico suggests that wood-inhabiting fungi may be highly diverse. In fact, it has been observed that high woody plant diversity is related to a high diversity of wood-inhabiting fungal species (Heilmann-Clausen et al., 2005; Unterseher et al., 2005). The diversity of the aphyllophoroid fungi is known to be influenced by several factors, of which host species diversity is one of the most important (Ódor et al., 2006). Actually, wood-inhabiting fungal species are very specific to their hosts, and fungal communities are significantly different depending on the vegetation type (Heilmann-Clausen et al., 2005; Unterseher et al., 2005). Thus, wood-inhabiting fungi represent one of the most diverse groups of wood-decaying organisms (Stokland et al., 2012). The most frequent wood-inhabiting fungal species belong to the Basidiomycota, including 2 main groups: polyporoid and corticioid fungi. These 2 groups have traditionally been placed in the order Aphyllophorales, but the molecular approach has drastically changed this classical classification (Hibbett et al., 2007; Matheny et al., 2007).

Concerning studies on Mexican fungi published to date, e.g. Valenzuela et al. (2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2010, 2012a and 2012b), Raymundo and Valenzuela (2003), Montaño et al. (2006), Marmolejo and Méndez-Cortes (2007), Raymundo et al. (2009), Amalfi et al. (2012), Contreras-Pacheco et al. (2012) and Salinas-Salgado et al. (2012). It is worth mentioning that although a large number of new records of fungi species have been published, some fungal groups and some parts of Mexico have not been thoroughly explored. This is the case of some aphyllophoroid fungi, and particularly corticioid fungi, which have not been properly studied until now. Among the territories not studied in depth, the state of Aguascalientes stands out: although it is an important area with numerous protected sites, few mycological studies have been conducted. According to our bibliographic resources, the only published work on Aguascalientes (Pardavé et al., 2007) reports 342 mushroom species, of which 46 were polyporoid and only 2 were corticioid.

Aguascalientes is located in the center of Mexico, and has 2 climate types: it is mostly arid, but in the western mountains, areas of temperate climate can be found (Inegi, 2008). These climates have generated a variety of vegetation types in the state. Based on species dominance, Rodríguez et al. (2011) classifies 28 types of natural plant communities in Aguascalientes, the main ones being needle leaf, mixed and broadleaf forest, high scrubland, deciduous tropical forest, subtropical scrubland, arid open forest, arid and semiarid scrubland. The principal genera of trees and bushes in the state are Quercus, Pinus, Juniperus, Arbutus, Arctostaphylos, Acacia, Ipomoea, Prosopis, Yucca and Opuntia. In an attempt to preserve the natural resources of Aguascalientes, 25% of the territory has been placed under some degree of official protection (Lozano and Estrada, 2008). The following sites have been designated as natural parks: Sierra Fría (112 090 ha), Sierra del Laurel (19 195 ha), Cerro del Muerto (5 862 ha) and Serranía Juan Grande (2 589 ha).

Considering the high vegetation diversity, the number of protected areas in Aguascalientes and the fact that wood-inhabiting aphyllophoroid fungi are a relatively unexplored group in the territory, the objectives of this study are: 1) to provide a preliminary inventory of the wood-inhabiting aphyllophoroid species for the state, and 2) to compare the aphyllophoroid communities of the plant communities sampled.

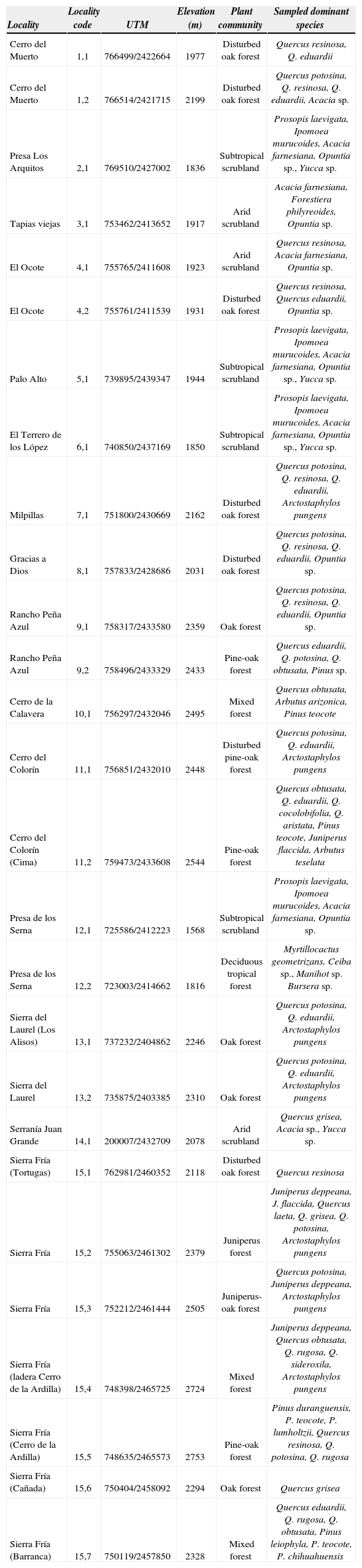

Materials and methodsThe study plots were located in the following different localities and municipalities of the state of Aguascalientes: San José de Gracia (Sierra Fría, Cerro El Colorín, Cerro de la Calavera, Rancho Peña Azul), Calvillo (Sierra del Laurel, Presa de los Serna, Palo Alto, El terrero de los López), Aguascalientes (El Ocote), Jesús María (Cerro del Muerto, Gracias a Dios, Milpillas, Tapias Viejas, Presa Los Arquitos) and El Llano (Serranía Juan Grande). The sites studied were grouped according to their matching proximity and vegetation type (Appendix). The geographical coordinates of the plots are displayed on the map of vegetation of Aguascalientes (Fig. 1).

Vegetation map of Aguascalientes. The sites where samples were collected are indicated by red points. Legend: A: agriculture, AU: urban area, BQa: open oak forest, BQa-VSAH: disturbed oak forest, BQ: oak forest, BQ-VSAH: disturbed oak forest, BP-BQ (BQ-BP): pine-oak forest, CA: water, MCr: arid scrubland, MCr-VSAH: disturbed arid scrubland, MSub: subtropical scrubland, MSub-VSAH: disturbed subtropical scrubland, PI: induced prairie, PN: natural prairie with Acacia.

The fieldwork was carried out in 2011, during the most favorable period for basidomata production (from July to September). Basidiomata collected were placed in paper bags in the field, and then dried and frozen for 72 hours in the laboratory. The date, locality, type of vegetation and host species data were recorded for each specimen. The dried material was identified by microscopic analyses using a Nikon light microscope. The preparations were made in Congo red KOH 5%, Melzer's reagent, and sulphovanilline. Voucher specimens have been deposited in the BIO-Fungi Herbarium in the University of the Basque Country (Spain).

Species were identified mostly following Eriksson and Ryvarden (1973, 1975, 1976); Eriksson et al. (1978, 1981, 1984); Breitenbach and Kränzlin (1986); Gilbertson and Ryvarden (1986); Hjortstam et al. (1987, 1988); Tellería and Melo (1995); Bernicchia (2005); Bernicchia and Gorjón (2010). Specific literature was consulted, such as Burdsall (1985); Langer (1994); Kõljalg (1996);Núñez and Ryvarden (1997); Léger (1998); Boidin and Gilles (1988). Fungal names were updated according to Index Fungorum (2013) (www.indexfungorum.org).

Species richness (S) and the Shannon diversity index [H'= -Σpi Ln (pi)] were calculated to explore and compare the number of species found in the different types of vegetation. Similarly, multivariate analysis was carried out to evaluate and compare aphyllophoroid communities, using the PRIMER 6 software package (Clarke and Gorley, 2006). As well, the Bray-Curtis resemblance index was used to gauge the similarity of aphyllophoroid communities (Clarke and Warwick, 2001). A non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was conducted to observe the grouping of aphyllophoroid communities of the different plant communities based on presence/absence data. Cluster classification analysis was also superimposed on the MDS to show the percentage of similarity between aphyllophoroid communities. Finally, a Simprof permutation test was run to find statistical differences between the groups formed.

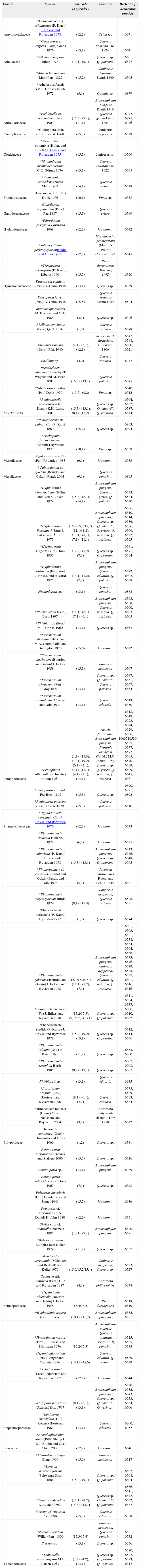

ResultsIn total, 308 specimens were collected during the sampling period, from which 81 species were identified (Table 1). These species belonged to 43 genera, distributed into 18 families and some species in Incertae sedis. The best-represented families were Phanerochaetaceae Jülich (with 14 species), Meruliaceae P. Karst. (12 species), Polyporaceae Fr. ex Corda (10) and Hymenochaetaceae Lév. (8). Phanerochaete P. Karst. and Hyphoderma Wallr. were the genera with the highest number of recorded species (10 and 5 respectively). The most frequent species were Phanerochaete galactites (Bourdot and Galzin) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden (20 specimens), Peniophora albobadia (Schwein.) Boidin (17), Hyphoderma litschaueri (Burt) J. Erikss. and Å. Strid (15) and Schizopora paradoxa(Schrad.) Donk (10).

List of species found in this study, showing the location and the substrate where they were found. *New records for Aguascalientes

| Family | Species | Site code (Appendix) | Substrate | BIO-Fungi herbarium number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylocorticiaceae | *Ceraceomyces cf. sulphurinus (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1978 | (12,2) | Ceiba sp. | 16971 |

| *Ceraceomyces serpens (Tode) Ginns 1976 | (13,1) | Quercus potosina Trel. 1924 | 16641 | |

| Atheliaceae | *Athelia acrospora Jülich 1972 | (13,1), (9,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16661, 16877 |

| *Athelia bombacina (Link) Pers. 1822 | (15,2) | Juniperus deppeana Stend. 1840 | 16505 | |

| *Athelia pyriformis (M.P. Christ.) Jülich 1972 | (3,1) | Opuntia sp. | 16879 | |

| Auriculariaceae | *Eichleriella cf. leucophaea Bres. 1903 | (15,3), (7,1), (11,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens Kunth 1818, Quercus grisea Liebm 1854 | 16977, 16975, 16976 |

| Coniophoraceae | *Coniophora arida (Fr.) P. Karst. 1868 | (15,3) | Juniperus deppeana | 16529 |

| Corticiaceae | *Dendrothele commixta (Höhn. and Litsch.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1975 | (15,3) | Juniperus sp. | 16509 |

| *Mutatoderma brunneocontextum C.E. Gómez 1976 | (13,1) | Quercus eduardii Trel. 1922 | 16655 | |

| *Vuilleminia comedens (Nees) Maire 1902 | (14,1) | Quercus grisea | 16628 | |

| Fomitopsidaceae | Antrodia serialis (Fr.) Donk 1966 | (10,1) | Pinus sp. | 16558 |

| Ganodermataceae | Ganoderma applanatum (Pers.) Pat. 1887 | (15,3) | Quercus grisea | 16549 |

| Hydnodontaceae | *Fibrodontia gossypina Parmasto 1968 | (12,2) | Unknown | 16542 |

| *Subulicystidium perlongisporumBoidin and Gilles 1988 | (12,2) | Myrtillocactus geometrizans (Mart. Ex Pfeiff.) Console 1897 | 16545 | |

| *Trechispora microspora (P. Karst.) Liberta 1966 | (15,5) | Pinus durangensis Martínez 1942 | 16520 | |

| Hymenochaetaceae | Fuscoporia contigua (Pers.) G. Cunn. 1948 | (13,1) | Quercus sp. | 16859 |

| Fuscoporia ferrea (Pers.) G. Cunn. 1948 | (15,5) | Quercus resinosa Liebm 1854 | 16524 | |

| Inonotus quercustris M. Blackw. and Gilb. 1985 | (3,1) | Quercus sp. | 16626 | |

| Phellinus conchatus (Pers.) Quél. 1886 | (1,2) | Quercus resinosa | 16578 | |

| Phellinus rimosus (Berk.) Pilát 1940 | (4,1), (3,1), (12,1) | Acacia sp., A. farnesiana (L.) Willd. 1806 | 16547, 16548, 16620, 16621 | |

| Phellinus sp. | (4,2) | Quercus resinosa | 16942 | |

| Pseudochaete tabacina (Sowerby) T. Wagner and M. Fisch. 2002 | (15,3), (13,1) | Quercus potosina | 16875 | |

| *Tubulicrinis calothrix (Pat.) Donk 1956 | (15,7), (9,2) | Pinus sp. | 16540, 16612 | |

| Incertae sedis | *Peniophorella praetermissa (P. Karst.) K.H. Larss. 2007 | (15,3), (13,1), (8,1), (11,2) | Quercus sp., Q. eduardii, Q. resinosa. | 16504, 16562, 16587, 16644 |

| *Peniophorella aff. pubera (Fr.) P. Karst. 1889 | (15,2) | Quercus sp. | 16893, 16894 | |

| *Trichaptum fuscoviolaceum (Ehrenb.) Ryvarden 1972 | (10,1) | Pinus sp. | 16559 | |

| Meripilaceae | Rigidoporus crocatus (Pat.) Ryvarden 1983 | (6,1) | Unknown | 16633 |

| Meruliaceae | *Cabalodontia cf. queletii (Bourdot and Galzin) Piatek 2004 | (9,1) | Quercus potosina | 16895 |

| *Hyphoderma cremeoalbum (Höhn. and Litsch.) Jülich 1974 | (15,3), (8,1), (14,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus grisea, Q. potosina | 16533, 16584, 16630 | |

| *Hyphoderma litschaueri (Burt) J. Erikss. and Å. Strid 1975 | (15,2/15,3/15,7), (11,1/11,2), (13,1), (8,1), (7,1), (11,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus sp., Q. eduardii, Q. grisea, Q. potosina, Q. resinosa | 16506, 16510, 16514, 16536, 16556, 16569, 16592, 16595 | |

| *Hyphoderma setigerum (Fr.) Donk 1957 | (12,2), (1,2), (7,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16541, 16571, 16594 | |

| *Hyphoderma sibiricum (Parmasto) J. Erikss. and Å. Strid 1975 | (13,1), (1,2), (7,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus eduardii, Q. potosina | 16572, 16602, 16658 | |

| Hyphoderma sp. | (13,1) | Quercus potosina | 16883 | |

| *Phlebia livida (Pers.) Bres. 1897 | (11,1), (8,1), (7,1), (9,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus potosina, Q. resinosa | 16563, 16588, 16600, 16603, 16605 | |

| *Phlebia rufa (Pers.) M.P. Christ. 1960 | (13,1) | Quercus sp. | 16663 | |

| *Steccherinum ciliolatum (Berk. and M.A. Curtis) Gilb. and Budington 1970 | (15,6) | Unknown | 16522 | |

| *Steccherinum litschaueri (Bourdot and Galzin) J. Erikss. 1958 | (15,3) | Juniperus deppeana | 16507 | |

| *Steccherinum ochraceum (Pers.) Gray 1821 | (13,1) | Quercus sp., Q. eduardii, Quercus potosina | 16647, 16651, 16657, 16664 | |

| *Steccherinum oreophilum Lindsey and Gilb. 1977 | (13,1) | Quercus eduardii | 16613, 16650 | |

| Peniophoraceae | *Peniophora albobadia (Schwein.) Boidin 1961 | (1,1), (15,3), (13,1), (9,2), (6,1), (2,1), (7,1), (11,1), (4,1), (3,1), (14,1) | Acacia farnesiana, Arctostaphylos pungens, Prosopis laevigata (Willd.) M.C. Johnst. 1962, Quercus sp., Q. grisea, Q. potosina, Q. resinosa | 16618, 16619, 16623, 16624, 16629, 16636, 1663716530, 16535, 16577, 16577, 16565, 16570, 16599, 16609, 16645, 16661 |

| *Peniophora aff. nuda (Fr.) Bres. 1897 | (15,3) | Quercus sp. | 16890, 16891, 16892 | |

| *Peniophora quercina (Pers.) Cooke 1879 | (15,3) | Quercus potosina | 16516 | |

| Phanerochaetaceae | *Hyphodermella corrugata (Fr.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1976 | (12,2) | Unknown | 16543 |

| *Phanerochaete aculeata Hallenb. 1978 | (6,1) | Unknown | 16635 | |

| *Phanerochaete calotricha (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1978 | (15,3), (13,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16513, 16646, 16648, 16665 | |

| *Phanerochaete cf. cacaina (Bourdot and Galzin) Burds. and Gilb. 1974 | (5,1) | Ipomoea murucoides Roem. and Schult. 1819 | 16631 | |

| *Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burds. 1974 | (8,1), (15.3) | Juniperus deppeana, Quercus resinosa | 16528, 16591 | |

| *Phanerochaete deflectens (P. Karst.) Hjortstam 1987 | (1,2) | Quercus sp. | 16574 | |

| *Phanerochaete galactites(Bourdot and Galzin) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1978 | (15,1/15,3/15,7) (11,1), (1,2), (7,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Juniperus deppeana, Quercus eduardii, Q. potosina, Q. resinosa | 16501, 16503, 16531, 16538, 16554, 16564, 16568, 16573, 16576, 16579, 16585, 16597, 16601, 16616, 16616 | |

| *Phanerochaete laevis (Fr.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1978 | (15,2/15,3), (9,1/9,2), (13,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16511, 16534, 16537, 16606, 16610, 16662 | |

| *Phanerochaete sordida (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden 1978 | (15,2), (9,2), (13,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16512, 16614, 16656 | |

| *Phanerochaete velutina (DC.) P. Karst. 1898 | (11,2) | Quercus sp. | 16553, 16560 | |

| *Phanerochaete xerophila Burds. 1985 | (9,2), (13,1) | Quercus sp. | 16607, 16608, 16667 | |

| Phlebiopsis sp. | (13,1) | Quercus eduardii | 16935 | |

| *Porostereum crassum (Lév.) Hjortstam and Ryvarden 1990 | (8,1), (6,1), (2,1) | Quercus resinosa | 16575, 16589, 16593, 16634 | |

| *Rhizochaete radicata (Henn.) Gresl., Nakasone and Rajchenb. 2004 | (3,1) | Forestiera phillyreoides (Benth.) Torr. 1858 | 16622 | |

| Polyporaceae | Dichomitus campestris (Quél.) Domanski and Orlicz 1966 | (1,2) | Quercus sp. | 16581 |

| Perenniporia meridionalis Decock and Stalpers 2006 | (15,7) | Quercus sp. | 16526 | |

| Perenniporia sp. | (13,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens | 16939 | |

| Perenniporia subacida (Peck) Donk 1967 | (7,1) | Quercus sp. | 16598 | |

| Polyporus alveolaris (DC.) Bondartsev and Singer 1941 | (15,7) | Unknown | 16936 | |

| Polyporus cf. meridionalis (A. David) H. Jahn 1980 | (12,2) | Unknown | 16551 | |

| Skeletocutis cf. ochroalba Niemelä 1985 | (13,1), (7,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens | 16680, 16681 | |

| Skeletocutis nivea (Jungh.) Jean Keller 1979 | (11,2) | Quercus sp. | 16557 | |

| Skeletocutis percandida (Malençon and Bertault) Jean Keller 1979 | (15,6/15,2/15,4) | Juniperus deppeana, Quercus sp. | 16523, 16527 | |

| Trametes aff. ochracea (Pers.) Gilb. and Ryvarden 1987 | (4,1) | Forestiera phillyreoides | 16978 | |

| Schizoporaceae | *Hyphodontia abieticola (Bourdot and Galzin) J. Erikss. 1958 | (15,4/15,5) | Pinus durangensis | 16518, 16519 |

| *Hyphodontia aspera (Fr.) J. Erikss. | (10,1), (11,2) | Arctostaphylos pungens | 16555, 16561 | |

| *Hyphodontia nespori (Bres.) J. Erikss. and Hjortstam 1976 | (15,2/15,3) | Arctostaphylos pungens Quercus obtusata Bonpl. 1809, potosina | 16515, 16525, 16533 | |

| Hyphodontia radula (Pers.) Langer and Vesterh. 1996 | (13,1), (15,6) | Quercus eduardii, Q. grisea | 16539, 16639 | |

| *Xylodon pruni (Lasch) Hjortstam and Ryvarden 2007 | (12.2) | Unknown | 16544 | |

| Schizopora paradoxa (Schrad.) Don 1967 | (8,1), (6,1), (13,1) | Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus sp., Q. eduardii, Q. resinosa | 16590, 16632, 16643, 16653, 16654, 16666 | |

| Stephanosporaceae | *Lindtneria chordulata (D.P. Rogers) Hjortstam 1987 | (13,1) | Quercus eduardii | 16960, 16957 |

| Stereaceae | *Acanthophysellum minor (Pilát) Sheng H. Wu, Boidin and C.Y. Chien 2000 | (12,2) | Unknown | 16546 |

| *Aleurodiscus thujae Ginns 1990 | (15,6) | Juniperus deppeana | 16517 | |

| *Stereum ochraceoflavum (Schwein.) Sacc. 1888 | (15,3), (9,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina | 16502, 16508, 16604 | |

| *Stereum reflexulum D.A. Reid 1969 | (11,1), (9,2), (15,3), (13,1) | Quercus sp., Q. eduardii, Q. potosina | 16566, 16611, 16642, 16652, 16887 | |

| Stereum cf. rugosum Pers. 1794 | (15,3) | Quercus eduardii | 16888 | |

| Stereum hirsutum (Willd.) Pers. 1800 | (15,3/15,4) | Juniperus deppeana, Quercus potosina | 16521, 16532 | |

| Stereum sp. | (13,1) | Quercus sp. | 16956 | |

| Thelephoraceae | *Tomentella umbrinospora M.J. Larsen 1963 | (1,2), (4,2), (13,1) | Quercus sp., Q. potosina, Q. resinosa | 16580, 16582, 16583, 16617 |

Among the species studied, 55 are recorded for the first time in the state of Aguascalientes, and these are indicated by an asterisk in Table 1. Likewise, most of these are little known in the remaining Mexican states.

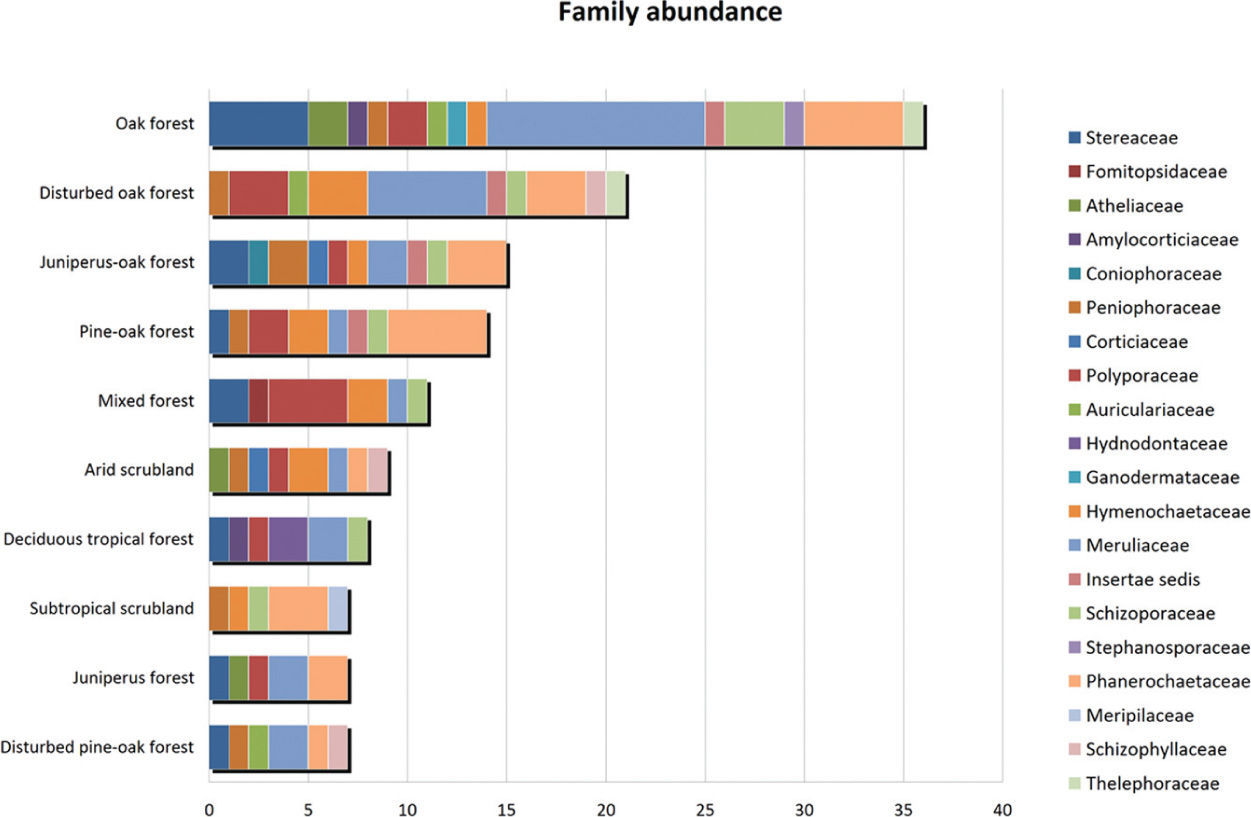

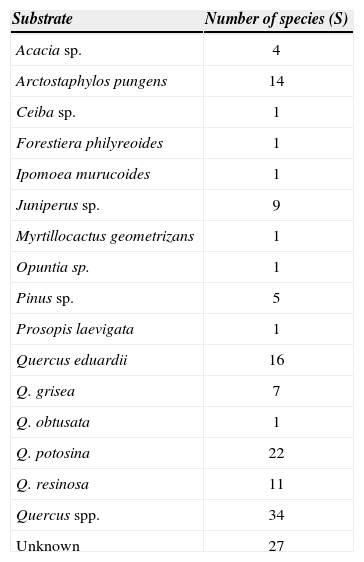

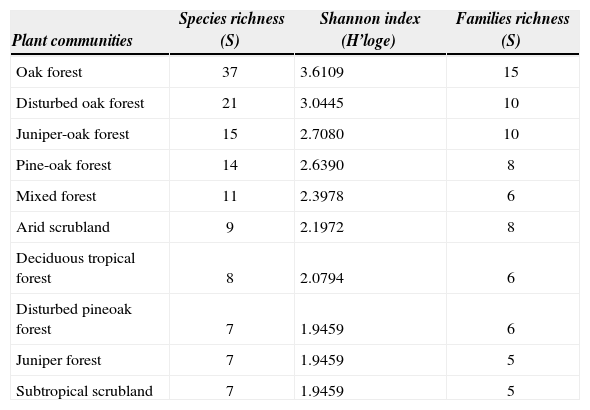

The genus Quercus had significantly more aphyllophoroid species than substrates of other genera. However, when the host species were analyzed one by one, Arctostaphylos pungens, Quercus eduardii and Q. potosina, were found to be the species that held most aphyllophoroid species (Table 2). Similarly, the highest fungal diversity was found in oak forest with 37 species and a diversity of 3.6 (H'=3.6), followed by disturbed oak forest with 21 species and H'=3.0 (Table 3). By contrast scrubland, deciduous tropical forest and juniper forest had the lowest fungal diversity with less than 10 species and H'<2.2 each (Table 3).

Number of species found per substrate

| Substrate | Number of species (S) |

|---|---|

| Acacia sp. | 4 |

| Arctostaphylos pungens | 14 |

| Ceiba sp. | 1 |

| Forestiera philyreoides | 1 |

| Ipomoea murucoides | 1 |

| Juniperus sp. | 9 |

| Myrtillocactus geometrizans | 1 |

| Opuntia sp. | 1 |

| Pinus sp. | 5 |

| Prosopis laevigata | 1 |

| Quercus eduardii | 16 |

| Q. grisea | 7 |

| Q. obtusata | 1 |

| Q. potosina | 22 |

| Q. resinosa | 11 |

| Quercus spp. | 34 |

| Unknown | 27 |

Species and family richness, and Shannon diversity index (H') for each plant community

| Plant communities | Species richness (S) | Shannon index (H’loge) | Families richness (S) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oak forest | 37 | 3.6109 | 15 |

| Disturbed oak forest | 21 | 3.0445 | 10 |

| Juniper-oak forest | 15 | 2.7080 | 10 |

| Pine-oak forest | 14 | 2.6390 | 8 |

| Mixed forest | 11 | 2.3978 | 6 |

| Arid scrubland | 9 | 2.1972 | 8 |

| Deciduous tropical forest | 8 | 2.0794 | 6 |

| Disturbed pineoak forest | 7 | 1.9459 | 6 |

| Juniper forest | 7 | 1.9459 | 5 |

| Subtropical scrubland | 7 | 1.9459 | 5 |

Oak forest and disturbed oak forest had the highest number of fungal species and families (Fig. 2), while subtropical scrubland forest, juniper forest and arid scrubland had the lowest species and family richness. Nevertheless, the plant communities with the highest species diversity had a lower family/species proportion value than the plant communities, which denotes a lower species diversity. That is, in the subtropical scrubland, juniper forest and arid scrubland the probability of a species belonging to a different family was found to be higher than in oak forest and disturbed oak forest. In fact, almost all of the species found in these plant communities belonged to different families.

In the MDS analysis, 3 significantly differentiated groups were identified by the Simprof procedure (Fig. 3). The principal factor for the differentiation of fungal composition was the woody species of the different plant communities. In fact, the plant communities with Quercus species constituted one distinct group, those with scrub species formed another and those with tropical species comprised a third. Likewise, within each group the similarity of the aphyllophoroid communities was higher when more woody species were shared.

Regarding the species composition of the different plant communities, temperate forests have in common some species that are known as cosmopolites. Examples include H. litschaueri, Peniophorella praetermissa, Phanerochaete galactites, P. laevis (Fr.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden and P. sórdida (P. Karst.) J. Erikss and Ryvarden.

DiscussionAlthough the fieldwork for this study was carried out within a year, 81 species were identified. According to our data, 55 species were recorded for the first time in the area (these species are marked with an asterisk in Table 1).

Different patterns of species distribution were observed. Many of the species documented have a wide distribution, and occur in most continents, e.g. P. praetermissa, P. sordida and S. paradoxa, which are well known from deciduous forests and occur on a wide range of substrates (Breitenbach and Kränzlin, 1986). Other species are exclusive to the Americas, such as Inonotus quercustris, which is known from the USA on Quercus nigra (Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1986); from Mexico in Querétaro State on Quercus sp. (Valenzuela et al., 2013) and from Argentina on Lithraea ternifolia and on Acacia caven (Urcelay and Rajchenberg, 1999). Likewise, P. albobadia has been recorded from Mexico, USA, Central and South America on several substrates (Nakasone, 1990). Finally, other species that have previously been considered as American are currently being cited in other territories, e.g. Phanerochaete xerophila Burds., which has been reported by Burdsall (1985) as a common species from the Sonoran Desert, growing on dead fallen branches of shrubs, cacti and on Prosopis velutina. In our study we found this species on Quercus sp. in oak and pine-oak forests. The same species has also been reported from Uruguay on Scutia buxifolia (Martínez and Nakasone 2005) and from Cabo Verde on Sarcostenma daltonii, Prosopis sp., and on Phoenix atlantica (Tellería pers. comm.). Another example is Porostereum crassum, which is a common species in America and was first reported from Spain by Salcedo and Olariaga (2008). The number of aphyllophoroid species was found to be higher in temperate forests than in scrublands. This could be partially explained by the exceptionally dry conditions of the sampling year. In fact, the scrublands were particularly affected that year, while forests conserved more humid conditions required for basidiomata production. Thus, few specimens were gathered in scrublands and those collected were mostly in poor condition for identification. Therefore, the potential of scrublands to host mycobiota could be higher than observed in this study.

The MDS result was expected, as most fungal species are specific to their host (Stokland et al., 2012). The similarities in terms of woody plant composition between the different plant communities were reflected in the structure of the aphyllophoroid community. The first group identified corresponded to temperate forest formations, which share many woody plant species (e. g. Quercus spp., Arctostaphyllos pungens, etc.) and also have similar climate conditions that influence the fungal guild structure. Most of the species that appeared in all the temperate forest plant communities have a cosmopolitan distribution, e.g. H. litschaueri, P. praetermissa and P. galactites (Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). The second group, formed by arid and subtropical scrublands, also shares some species (cacti, Acacia spp. and Mimosa spp.) and similar climate conditions. Peniophora albobadia and P. rimosus were found in both types of scrubland. These species are characterized by being more common to the tropics, to warm and arid zones, although they are almost cosmopolitan (Boidin, 1994; Ryvarden and Gilbertson, 1994; Bernicchia, 2005). The only species that was not common to both types of scrubland (Phanerochaete cacaina (Bourdot and Galzin) Burds. and Gilb.) grew on Ipomoea murucoides, which is one of the woody plant species that differentiates between the 2 types. Nevertheless, this species does not seem to be exclusive in this plant community, since it has been reported on Pinus in Europe and the USA (Burdsall, 1985; Eriksson et al., 1978). Finally, the fungal composition of deciduous tropical forest proved to be the most dissimilar of all the plant communities. This plant community is dominated by woody species that do not occur anywhere else in Aguascalientes (Manihot sp., Ceiba sp., Amphipterygium adstringens, among others), which could explain the dissimilarities in fungal composition. However, this result must be taken with caution since the majority of the species identified were cosmopolitan, although some tropical species also appeared (Subulicystidium perlongisporum Boidin and Gilles). Further investigations are needed to determine if this trend is maintained throughout deciduous tropical forest.

To the working group of the botany lab of the UAA for their support in fieldwork, and especially Gabriela Delgadillo Quesada for coming with us to the sampling sites, her help has been invaluable. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for thoroughly reviewing the manuscript and for their constructive comments.

List of localities sampled with their elevation and dominant plant community.

| Locality | Locality code | UTM | Elevation (m) | Plant community | Sampled dominant species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerro del Muerto | 1,1 | 766499/2422664 | 1977 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus resinosa, Q. eduardii |

| Cerro del Muerto | 1,2 | 766514/2421715 | 2199 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. resinosa, Q. eduardii, Acacia sp. |

| Presa Los Arquitos | 2,1 | 769510/2427002 | 1836 | Subtropical scrubland | Prosopis laevigata, Ipomoea murucoides, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp., Yucca sp. |

| Tapias viejas | 3,1 | 753462/2413652 | 1917 | Arid scrubland | Acacia farnesiana, Forestiera philyreoides, Opuntia sp. |

| El Ocote | 4,1 | 755765/2411608 | 1923 | Arid scrubland | Quercus resinosa, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp. |

| El Ocote | 4,2 | 755761/2411539 | 1931 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus resinosa, Quercus eduardii, Opuntia sp. |

| Palo Alto | 5,1 | 739895/2439347 | 1944 | Subtropical scrubland | Prosopis laevigata, Ipomoea murucoides, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp., Yucca sp. |

| El Terrero de los López | 6,1 | 740850/2437169 | 1850 | Subtropical scrubland | Prosopis laevigata, Ipomoea murucoides, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp., Yucca sp. |

| Milpillas | 7,1 | 751800/2430669 | 2162 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. resinosa, Q. eduardii, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Gracias a Dios | 8,1 | 757833/2428686 | 2031 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. resinosa, Q. eduardii, Opuntia sp. |

| Rancho Peña Azul | 9,1 | 758317/2433580 | 2359 | Oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. resinosa, Q. eduardii, Opuntia sp. |

| Rancho Peña Azul | 9,2 | 758496/2433329 | 2433 | Pine-oak forest | Quercus eduardii, Q. potosina, Q. obtusata, Pinus sp. |

| Cerro de la Calavera | 10,1 | 756297/2432046 | 2495 | Mixed forest | Quercus obtusata, Arbutus arizonica, Pinus teocote |

| Cerro del Colorín | 11,1 | 756851/2432010 | 2448 | Disturbed pine-oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. eduardii, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Cerro del Colorín (Cima) | 11,2 | 759473/2433608 | 2544 | Pine-oak forest | Quercus obtusata, Q. eduardii, Q. cocolobifolia, Q. aristata, Pinus teocote, Juniperus flaccida, Arbutus teselata |

| Presa de los Serna | 12,1 | 725586/2412223 | 1568 | Subtropical scrubland | Prosopis laevigata, Ipomoea murucoides, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp. |

| Presa de los Serna | 12,2 | 723003/2414662 | 1816 | Deciduous tropical forest | Myrtillocactus geometrizans, Ceiba sp., Manihot sp. Bursera sp. |

| Sierra del Laurel (Los Alisos) | 13,1 | 737232/2404862 | 2246 | Oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. eduardii, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Sierra del Laurel | 13,2 | 735875/2403385 | 2310 | Oak forest | Quercus potosina, Q. eduardii, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Serranía Juan Grande | 14,1 | 200007/2432709 | 2078 | Arid scrubland | Quercus grisea, Acacia sp., Yucca sp. |

| Sierra Fría (Tortugas) | 15,1 | 762981/2460352 | 2118 | Disturbed oak forest | Quercus resinosa |

| Sierra Fría | 15,2 | 755063/2461302 | 2379 | Juniperus forest | Juniperus deppeana, J. flaccida, Quercus laeta, Q. grisea, Q. potosina, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Sierra Fría | 15,3 | 752212/2461444 | 2505 | Juniperus-oak forest | Quercus potosina, Juniperus deppeana, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Sierra Fría (ladera Cerro de la Ardilla) | 15,4 | 748398/2465725 | 2724 | Mixed forest | Juniperus deppeana, Quercus obtusata, Q. rugosa, Q. sideroxila, Arctostaphylos pungens |

| Sierra Fría (Cerro de la Ardilla) | 15,5 | 748635/2465573 | 2753 | Pine-oak forest | Pinus duranguensis, P. teocote, P. lumholtzii, Quercus resinosa, Q. potosina, Q. rugosa |

| Sierra Fría (Cañada) | 15,6 | 750404/2458092 | 2294 | Oak forest | Quercus grisea |

| Sierra Fría (Barranca) | 15,7 | 750119/2457850 | 2328 | Mixed forest | Quercus eduardii, Q. rugosa, Q. obtusata, Pinus leiophyla, P. teocote, P. chihuahuensis |