The “Recherches zoologiques” of the “Mission scientifique au Mexique et dans l’Amérique Centrale” (“Mission” hereafter), were published as “livraisons” (deliveries) over a period of nearly half a century between 1870 and 1916. Henri Milne-Edwards, head of the Laboratoire des Mammifères et Oiseaux, was the editor of the whole publication; after his death, the editorial work was continued by Alphonse Milne-Edwards, his son, and Léon Louis Vaillant. “Recherches zoologiques” were intended to include 7 parts (“parties”): Première partie: “Anthropologie du Mexique”. Deuxième partie: not published. Troisième partie: “Études sur les Reptiles”. Quatrième partie: “Études zoologiques sur les Poissons…”. Cinquième partie: “Études sur Xiphosures et les Crustacés…”. Sixième partie: “Études sur les Insectes Orthoptères and Études sur les Myriapodes”. Septième partie: “Études sur les Mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles”. See Crosnier and Clark (1998) for more details. The “Recherches zoologiques” were themselves a division of the more comprehensive “Mission” series including: 1 – “Les travaux préparatoires et le suivi des événements” (1864–1877), 2 – “Géologie” (1868–1871), 3 – “Linguistique” (1869–1885), 4 – “Recherches botaniques” (1872–1886), 5 – “Recherches historiques et archéologiques” (1885), 6 – “Recherches zoologiques” (1870–1916). These divisions were comparatively of very unequal importance, at least judging by the number of published pages.

The “Reptiles and Amphibians” (the latter called “Batraciens”), making up the third part, was originally subtitled “Étude sur les Reptiles et Batraciens”, but later was split into 2 sections. Different sections of the third part are variously attributed, according to different published references, to Henri Milne-Edwards (1800–1885), Auguste Henri André Duméril (1812–1870), Marie Firmin Bocourt (1819–1904), Paul Brocchi (1838–1898), François Mocquard (1834–1917) and Léon Louis Vaillant (1834–1914), with some authorities even adding Fernand Angel (1881–1950) as author, e.g., Savage (2002: 39). In this third part Milne-Edwards only authored the “Introduction” to Brocchi's contribution (1882); the name of his son, Alphonse Milne-Edwards, is twice mentioned as author of amphibian plates in the same contribution. Duméril “filius”, head of the Laboratoire des Reptiles et Poissons since 1857, died on 12 November 1870, the very year of the publication of the first pages, and his contribution was limited to the “Introduction” to the whole herpetological part (cf. Milne-Edwards, 1882: 1), although he doubtless also participated in the original organization of the herpetological sections. By contrast, Firmin Bocourt, who worked at the Museum since 1834 as an assistant of the 2 Dumérils and later of Vaillant, was by far the principal author of the “Reptiles” section, for both text and illustrations. In 1881, following Milne-Edwards’ ruling, Bocourt, at the age of 62 (he was not then dead, as implied by Crosnier and Clark (1998: 95), he died on 4 February 1904, at the age of nearly 85), had to give up the “Amphibians” because he was so preoccupied with the “Reptiles”, and forwarded all of his notes and illustrations to Brocchi (1877a,b, 1881: 3) to write the “Batraciens” part. From then on, part 3 was split into 2 sections, and after Bocourt's death the subtitle “Études sur les Reptiles et Batraciens” was changed to “Études sur les Reptiles”. Léon Vaillant was the successor of A. Duméril as the head of the Laboratoire, from 1875 to 1909, although Émile Blanchard held the post on an interim basis from 1870 to 1875, and necessarily he had a role in the long production of the herpetological parts of the “Mission” project. Bocourt, Brocchi, Mocquard, and Angel were under Vaillant's direction, but Vaillant only authored the eight-page “Avant-propos”, which was placed at the beginning of the Reptiles section. Together with Bocourt, Vaillant was the author of the fourth part, “Études zoologiques sur les Poissons…”, of which the last “livraison” was published posthumously (1916). François Mocquard was approximately the same age as Léon Vaillant, but he began to work at the laboratory much later, from 1884, and was promoted to Assistant in 1891; he completed the “Reptiles” section left from the death of Bocourt, and he wrote some 110 pages to complete this section. Finally, the name of Fernand Angel appeared only as the artist for the last six plates of “Reptiles” (1909); he began work at the Museum in 1905.

After it was published, the “Étude sur les Reptiles et Batraciens” got few and rather negative reviews, notably from Gray (1873), who was latter vindicated (Anonymous, 1874a), and Cope (1884). Subsequently, however, it has been considered an important and even essential taxonomic work for the region (Adler, 2007, 2014; Flores-Villela, 1993; Smith & Smith, 1973), because dozens of new taxa from Mexico, Central America and the West Indies are first named in this book, with fine illustrations and detailed descriptions. In modern times this work has not been easy to access because it is absent from many institutional libraries in Mexico and Central America and because most herpetologists in that part of the world do not read French. However, a facsimile reprint of the entire herpetological section was published in 1978 (Arno Press, New York), and the text (Reptiles only, without illustrations) is currently available on the Internet at https://books.google.fr/books?id=oItuSppLGVAC.

During some work related to the type specimens of species described by Alfredo Dugès and located in the Museo de Historia Natural Alfredo Dugès, of the University of Guanajuato (Flores-Villela, Ríos-Muñoz, Magaña-Cota, & Quezadas-Tapia, 2016), one of us (OFV) encountered a problem with the authorship of one taxon. The difficulty and the confusion to assign a proper author to such a taxon has led us to present the following tables. A first attempt was a table partly adapted from Vaillant (1909a: viii), who wrote the “Avant-propos”, as noted above. This table was greatly enhanced thanks to published data and our unpublished data.

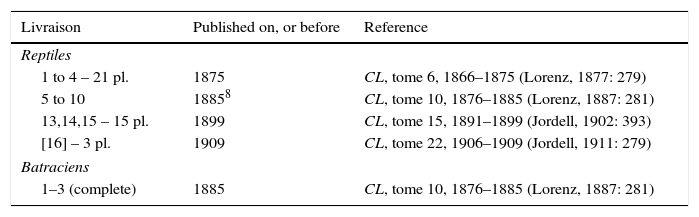

In his table, Vaillant did not give details regarding authorship for the different parts of the text or plates, but detailed the splitting of the work into “livraisons”. Much later, Smith and Smith (1973: x), based on a personal communication from Edward H. Taylor, published a list of the publication dates and authorship of the different parts, but unfortunately it lacks the relationship between “livraisons, feuilles” (printed leaves of paper) and pages, and has some inaccuracies. More recently, Crosnier and Clark (1998) wrote a very detailed study of the entire “Mission” publication and its 7 parts including their sections, which is by far the most complete, and with data about authorships and pagination. Crosnier & Clark correctly recognized part 3 as including the “Reptiles” (1998: 88) but later (1998: 95) erroneously gave it the number 2. These authors outlined several editorial blunders and odd changes which appeared during the 46 years of publication. They also minutely analyzed all the volumes of the “Bibliographie de la France”, from 1873 to 1916, noting all data in connection with the “Mission” series of works. In the series “Catalogue général de la Librairie française” the data are both incomplete and sometimes imprecise, see Table 3. The only point to note is that the year of publication suggested for the 10th “livraison”, 1885, disagrees with the date given here, 1886, which is also the date given on the original wrappers. An important notice about the administrative history of the whole “Mission” was recently published by the French “Archives nationales” (Le Goff & Prévost-Urkidi, 2009), but it does not include any detail about the dates of publication; for the “Reptiles”, they only gave the inclusive dates 1870–1909 and for the “Amphibians”, 1882, which is correct only for the second section of this book. As outlined by Crosnier and Clark (1998: 90): “… it was particularly regrettable that the “Imprimerie nationale” (or “impériale”, till 1870), which published the various “livraisons”, did not appear to possess any archive relative to the exact dates of publication”.

When available, years of publication of the “livraisons”, according to the records of the “Catalogue général de la Librairie française” (CL hereunder).

| Livraison | Published on, or before | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | ||

| 1 to 4 – 21 pl. | 1875 | CL, tome 6, 1866–1875 (Lorenz, 1877: 279) |

| 5 to 10 | 18858 | CL, tome 10, 1876–1885 (Lorenz, 1887: 281) |

| 13,14,15 – 15 pl. | 1899 | CL, tome 15, 1891–1899 (Jordell, 1902: 393) |

| [16] – 3 pl. | 1909 | CL, tome 22, 1906–1909 (Jordell, 1911: 279) |

| Batraciens | ||

| 1–3 (complete) | 1885 | CL, tome 10, 1876–1885 (Lorenz, 1887: 281) |

For the 10th livraison, year 1885 disagrees with the currently admitted year 1886, based on the wrapper and on Vaillant 1909a, corroborated by the “Bibliographie de la France” (Table 4).

Actually, the only accurate way to get the most probable dates of publication is to examine copies that still have the original wrappers or covers of the “livraisons”. Crosnier & Clark could only find 2 sets that still have all wrappers, one at the French National Library (“Bibliothèque Nationale”) in Paris, and the other one in the Zoology Library of the Natural History Museum, London. Another one was bought in 1962 in Paris by one of us (KA), who kept all of these wrappers and communicated the dates to Hobart Smith for his book (Smith & Smith, 1976: App-1). Crosnier & Clark also compared dates from wrappers with dates of published accounts, and concluded that because all of them are in accordance, the dates of the wrappers can be considered as reliable. The only disagreement appears with “livraison” 15, where the year (wrapper and Vaillant's table) is given as 1897, but the precise date of registration by the “Bibliographie de la France” is stated as 17 January 1898 (cf. Table 4, note 10).

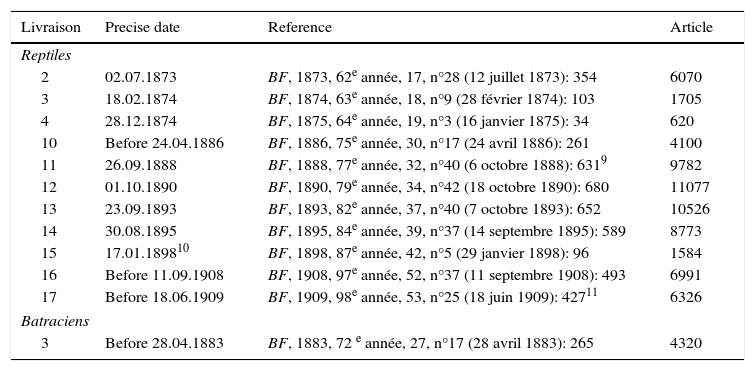

Precise dates, when available, of the publication of the “livraisons”, according to the records of the “Bibliographie de la France. Journal général de l’Imprimerie et de la Librairie”, 2e série (BF hereunder).

| Livraison | Precise date | Reference | Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | |||

| 2 | 02.07.1873 | BF, 1873, 62e année, 17, n°28 (12 juillet 1873): 354 | 6070 |

| 3 | 18.02.1874 | BF, 1874, 63e année, 18, n°9 (28 février 1874): 103 | 1705 |

| 4 | 28.12.1874 | BF, 1875, 64e année, 19, n°3 (16 janvier 1875): 34 | 620 |

| 10 | Before 24.04.1886 | BF, 1886, 75e année, 30, n°17 (24 avril 1886): 261 | 4100 |

| 11 | 26.09.1888 | BF, 1888, 77e année, 32, n°40 (6 octobre 1888): 6319 | 9782 |

| 12 | 01.10.1890 | BF, 1890, 79e année, 34, n°42 (18 octobre 1890): 680 | 11077 |

| 13 | 23.09.1893 | BF, 1893, 82e année, 37, n°40 (7 octobre 1893): 652 | 10526 |

| 14 | 30.08.1895 | BF, 1895, 84e année, 39, n°37 (14 septembre 1895): 589 | 8773 |

| 15 | 17.01.189810 | BF, 1898, 87e année, 42, n°5 (29 janvier 1898): 96 | 1584 |

| 16 | Before 11.09.1908 | BF, 1908, 97e année, 52, n°37 (11 septembre 1908): 493 | 6991 |

| 17 | Before 18.06.1909 | BF, 1909, 98e année, 53, n°25 (18 juin 1909): 42711 | 6326 |

| Batraciens | |||

| 3 | Before 28.04.1883 | BF, 1883, 72 e année, 27, n°17 (28 avril 1883): 265 | 4320 |

Note added to the account: “Les pages 657 à 660 dans cette livraison doivent remplacer les pages 657 à 660 de la livraison précédente”.

In the account the date is given as follows: “(17 janvier.) (1897.)”. That means that the “livraison” was registered on 17 January 1898, and either the author considered it nevertheless appeared in 1897, or, more probably, he alluded to the date written on the wrapper. Crosnier and Clark (2008: 95) had another interpretation and gave 17.01.1897 as date of registration.

Omitted by Crosnier and Clark (2008: 95). It was only on 21 December 1909 that Vaillant gave to the Bibliothèque du Muséum the two last livraisons (Vaillant, 1909b: 516).

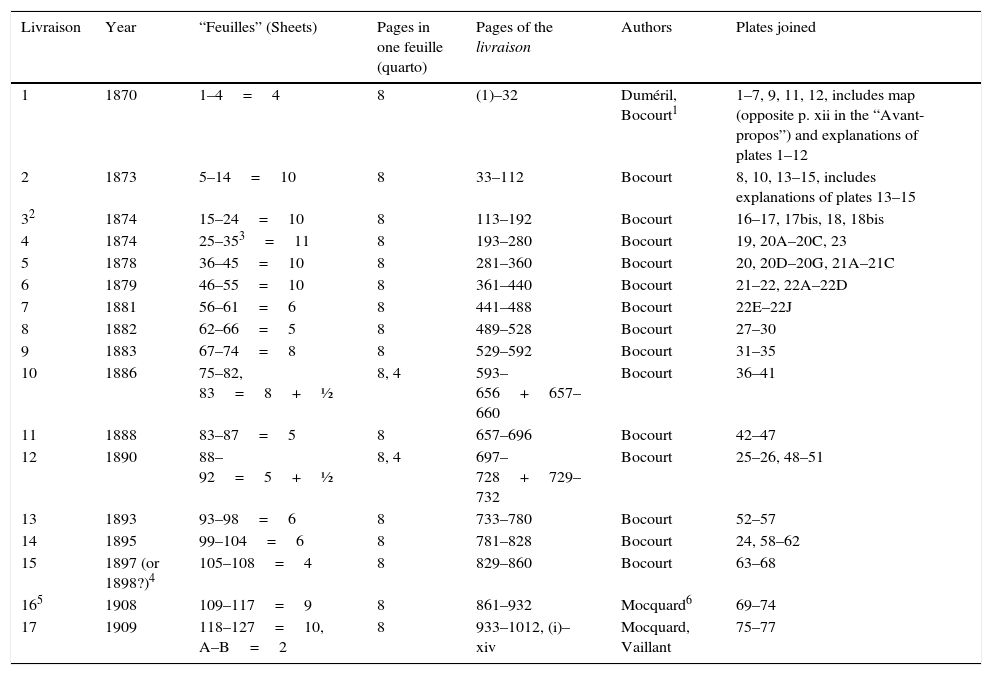

With this set of data we believe it is important to make available the details of the publication of the “Mission” for the “Reptiles” and “Amphibians”, so that mistakes concerning the authorship and year of publications are not disseminated, creating confusion and nomenclatural problems. Therefore, Table 1 (“Reptiles”) and Table 2 (“Batraciens”=“Amphibians”) detail which of the authors of this work is responsible for the different parts of it. Table 4 provides, when available, precise dates of publication, according to the weekly journal “Bibliographie de la France”, which had the aim to give an exhaustive list of all printed matters as soon as they appeared. These tables may serve as a guide when citing particular “livraisons” in references about the “Mission”, rather than referring to the work in its entire form. Table 5 gives the artists for the plates, most always following their mention at the bottom of individual plates. Despite careful research, it has been impossible to find any biographical data about some of these artists, and even a first name remains missing for 2 of them (see Appendix).

Data about the publication of the “Mission scientifique au Mexique et dans l’Amérique Centrale”, “Reptiles”. Years of publication based on the date printed on the wrappers.

| Livraison | Year | “Feuilles” (Sheets) | Pages in one feuille (quarto) | Pages of the livraison | Authors | Plates joined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1870 | 1–4=4 | 8 | (1)–32 | Duméril, Bocourt1 | 1–7, 9, 11, 12, includes map (opposite p. xii in the “Avant-propos”) and explanations of plates 1–12 |

| 2 | 1873 | 5–14=10 | 8 | 33–112 | Bocourt | 8, 10, 13–15, includes explanations of plates 13–15 |

| 32 | 1874 | 15–24=10 | 8 | 113–192 | Bocourt | 16–17, 17bis, 18, 18bis |

| 4 | 1874 | 25–353=11 | 8 | 193–280 | Bocourt | 19, 20A–20C, 23 |

| 5 | 1878 | 36–45=10 | 8 | 281–360 | Bocourt | 20, 20D–20G, 21A–21C |

| 6 | 1879 | 46–55=10 | 8 | 361–440 | Bocourt | 21–22, 22A–22D |

| 7 | 1881 | 56–61=6 | 8 | 441–488 | Bocourt | 22E–22J |

| 8 | 1882 | 62–66=5 | 8 | 489–528 | Bocourt | 27–30 |

| 9 | 1883 | 67–74=8 | 8 | 529–592 | Bocourt | 31–35 |

| 10 | 1886 | 75–82, 83=8+½ | 8, 4 | 593–656+657–660 | Bocourt | 36–41 |

| 11 | 1888 | 83–87=5 | 8 | 657–696 | Bocourt | 42–47 |

| 12 | 1890 | 88–92=5+½ | 8, 4 | 697–728+729–732 | Bocourt | 25–26, 48–51 |

| 13 | 1893 | 93–98=6 | 8 | 733–780 | Bocourt | 52–57 |

| 14 | 1895 | 99–104=6 | 8 | 781–828 | Bocourt | 24, 58–62 |

| 15 | 1897 (or 1898?)4 | 105–108=4 | 8 | 829–860 | Bocourt | 63–68 |

| 165 | 1908 | 109–117=9 | 8 | 861–932 | Mocquard6 | 69–74 |

| 17 | 1909 | 118–127=10, A–B=2 | 8 | 933–1012, (i)–xiv | Mocquard, Vaillant | 75–77 |

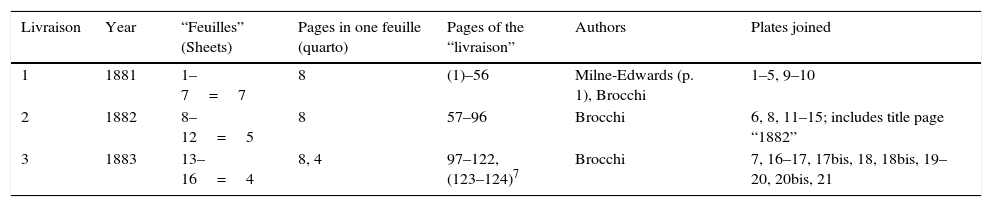

Data about the publication of the “Mission scientifique au Mexique et dans l’Amérique Centrale”, Amphibians (as “Batraciens”).

| Livraison | Year | “Feuilles” (Sheets) | Pages in one feuille (quarto) | Pages of the “livraison” | Authors | Plates joined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1881 | 1–7=7 | 8 | (1)–56 | Milne-Edwards (p. 1), Brocchi | 1–5, 9–10 |

| 2 | 1882 | 8–12=5 | 8 | 57–96 | Brocchi | 6, 8, 11–15; includes title page “1882” |

| 3 | 1883 | 13–16=4 | 8, 4 | 97–122, (123–124)7 | Brocchi | 7, 16–17, 17bis, 18, 18bis, 19–20, 20bis, 21 |

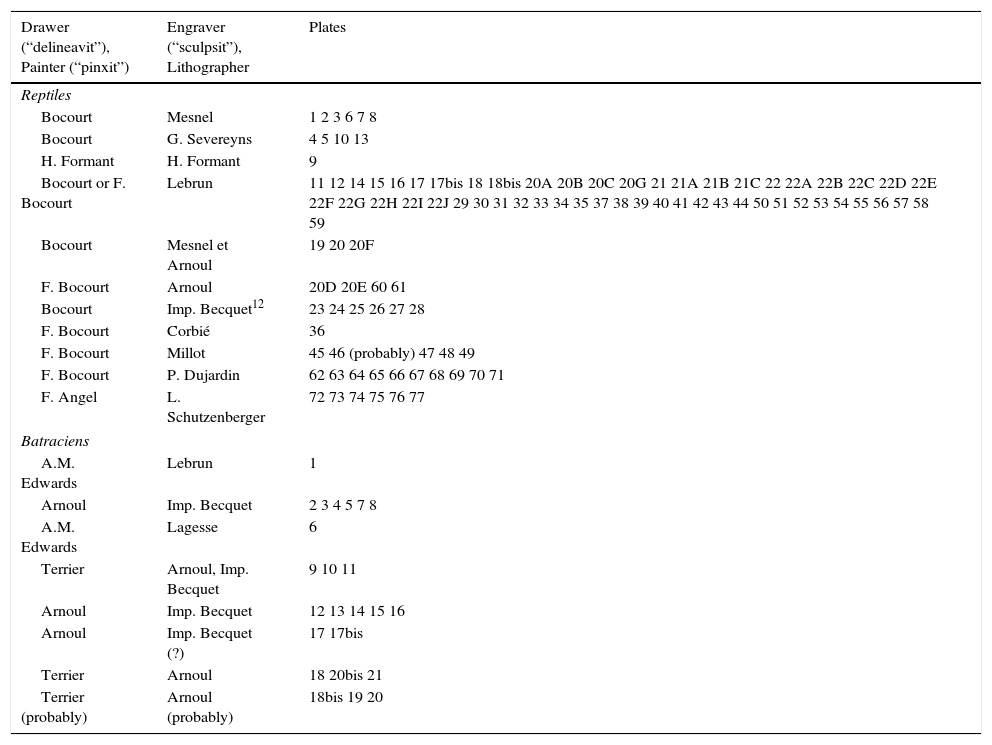

Artists who illustrated the “Reptiles” and “Amphibians” (as “Batraciens”).

| Drawer (“delineavit”), Painter (“pinxit”) | Engraver (“sculpsit”), Lithographer | Plates |

|---|---|---|

| Reptiles | ||

| Bocourt | Mesnel | 1 2 3 6 7 8 |

| Bocourt | G. Severeyns | 4 5 10 13 |

| H. Formant | H. Formant | 9 |

| Bocourt or F. Bocourt | Lebrun | 11 12 14 15 16 17 17bis 18 18bis 20A 20B 20C 20G 21 21A 21B 21C 22 22A 22B 22C 22D 22E 22F 22G 22H 22I 22J 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 |

| Bocourt | Mesnel et Arnoul | 19 20 20F |

| F. Bocourt | Arnoul | 20D 20E 60 61 |

| Bocourt | Imp. Becquet12 | 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

| F. Bocourt | Corbié | 36 |

| F. Bocourt | Millot | 45 46 (probably) 47 48 49 |

| F. Bocourt | P. Dujardin | 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 |

| F. Angel | L. Schutzenberger | 72 73 74 75 76 77 |

| Batraciens | ||

| A.M. Edwards | Lebrun | 1 |

| Arnoul | Imp. Becquet | 2 3 4 5 7 8 |

| A.M. Edwards | Lagesse | 6 |

| Terrier | Arnoul, Imp. Becquet | 9 10 11 |

| Arnoul | Imp. Becquet | 12 13 14 15 16 |

| Arnoul | Imp. Becquet (?) | 17 17bis |

| Terrier | Arnoul | 18 20bis 21 |

| Terrier (probably) | Arnoul (probably) | 18bis 19 20 |

We would like to thank A. Bauer and J. A. Campbell for their kind help. OFV thanks the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), for their support during a sabbatical year at the University of Texas, Arlington (UTA). The authorities of UTA and UNAM are greatly appreciated for their support. We also thank A. Crosnier and P. F. Clark, who made the only complete and accurate study about the whole publication of the “Mission”, its “livraisons” and dates.

During the 19th century, painters and drawers working for the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle” were considered to be mere helpers, their role being to make illustrations under the supervision of the scientific staff. Although the artist's part of the publication was of primary importance, sometimes even the most lasting part of it, many of them were only mentioned by their surname, with or without their forename or just an abbreviation for it, which most often discreetly appeared at the lower left corner of the plates. They were almost never acknowledged in the text. Some artists were also the engravers or lithographers of their own drawings, but sometimes this work was assigned to other artists specializing in these techniques, whose names were also only given as surnames, and whose name appeared at the lower right corner of the plate. During the 19th century, these artists were numerous in France, as were lithographic printing companies, but most are completely forgotten today. From various sources, national archives, civil status of départements, dictionaries and other listings, and data from genealogical associations, etc. These biographies should be considered just a first step in giving these gifted artists their rightful recognition. The most famous dictionary of painters, sculptors, drawers and engravers (Bénézit, 1976, 2002) was especially disappointing on this point. The best sources were Claus Nissen (1978: section V. Künstler, pp. 511–604) and the Database of Scientific Illustrators (DSI) on the Internet (Anonymous, 2015). Today the memory of these artists remains mainly through their published plates (originals or facsimiles), which because of their aesthetic qualities are even offered for sale by specialized art galleries and print shops. On the other hand, biographies of those who were also appointed as scientists by the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle”, such as Angel, Bocourt, and Milne-Edwards, are not detailed.

Angel, Clément Fernand (Douzy, Ardennes 1881–Paris 1950). Herpetologist, curator, author, and first officially a drawer at the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle”, from 1905 to 1950.

Arnoul,Gustave (Paris 1835–Paris 1901). Although he was first officially a drawer at the Railways Company “Chemins de fer de l’Ouest”, he early began to create artistic works, before the age of 20, and produced a lot of oeuvres as both a painter and a lithographer, partly in connection with Imprimerie Becquet.

Becquet. Imprimerie Becquet, in Paris, was managed by a “dynasty” including Pierre Prudence Louis B. (Vernon 1796–Paris 1845), then his sons (the “frères Becquet”=Becquet brothers) Louis Lubin B. (Paris 1819–Mantes 1882) and Charles Germain B. (Paris 1825–Paris 1884), finally Louis Paul B. (Paris 1850–?) and Louis Alfred B. (1852–?), sons of the latter, and Eugène Paul B. (Paris 1855–?), son of the former. All were lithographers. The printing company sometimes employed as many as 12 workers at a given time. It was situated in Rue des Noyers, later merged with Boulevard Saint-Germain.

Bocourt, Marie Firmin (Paris 1819–Paris 1904). Artist, herpetologist, taxidermist, traveller, and collector; he worked at the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle” from 1834; he retired in 1892 but still worked there until his death. His father, Firmin Bocourt (Heilly, Somme 1787–Paris 1846), was himself an engraver.

Corbié (or Corbier). The name of Corbié appeared from 1835 to 1886 as a drawer and engraver; he used the process of intaglio (taille-douce). Madame Corbié was a colorist. The workshop was in the Quartier Latin (1839: Rue Serpente; 1862: Rue de la Harpe). No more details about this (or these: father then son?) Corbié were found. Several other Corbiés are known as having inhabited the same district.

Dujardin, Paul Rodolphe Joseph (Lille 1843–Paris 1913). Brother of Gustave Alexandre Rodolphe D. (1840–1893), a pharmacist then photographer. In 1875 Paul bought Gustave's workshop in Paris. He developed a factory of prints and plates engraved by intaglio process (heliogravure), improved by himself. His shop was in the Montparnasse district (Rue Vavin, with a branch in the former Passage Stanislas). In 1878 he was recipient of the “Légion d’Honneur”. Portrayed by Paul Marsan (http://www.piasa.fr/node/15366/lot/past).

Formant, Henri Célestin (Cambrai 1827–?). Student at the “École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts”. Painter and “préparateur à l’atelier de moulage du Muséum d’Histoire naturelle” (Assistant at the moulding workshop), 55 rue Buffon”; in 1896 he was nominated “Officier des Palmes Académiques”.

Lagesse, Lucien Victor (Paris 1822–Paris 1884). Drawer and engraver. In 1877 he was hired as “préparateur-dessinateur” at the laboratory of botany, “École pratique des hautes études” (EPHE), founded in 1868 at Paris. He inhabited Rue Campo Formio (13rd arrondissement).

Lebrun, L. (?–?), or Charles Dominique (Montrouge 1824–?), or Henri (1815–?), according to various references. He produced a great deal of work as a lithographer. In 1861, this engraver lived in Paris on Rue des Noyers (see Becquet).

Mesnel, Albin Auguste Marin (Paris 1830–Paris 1875). Drawer and engraver, he made chromolithographs as well as woodcuts, mainly of natural history subjects. His father was a tapestry maker at the Manufacture des Gobelins, where Mesnel spent his first years. Later he studied with Charles Delahaye, who worked as an illustrator and lithographer at the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle”.

Millot, Adolphe Philippe (Paris 1857–Paris 1921). Draftsman, painter and lithographer, he is well known as an illustrator of natural history subjects for various editions of Larousse dictionaries and encyclopaedias. From 1911 to 1921 he taught drawing (“iconographie animale”) at the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle”. He dwelled close to the Jardin des Plantes: Rue Lacepède, then Rue Monge.

Milne-Edwards, Alphonse (Paris 1835–Paris 1900). Son of Henri Milne-Edwards (he incorporated the middle name of his father — Milne — into his surname); a zoologist, he became Director of the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle” in 1891.

Schutzenberger, Louis-Frédéric (Strasbourg 1825–Strasbourg 1903). Studied at the “École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts”. He was mainly a painter of portraits and landscapes and not known to be a lithographer, so his participation in the “Mission” project is somewhat surprising.

Severeyns, Guillaume Albert Charles, usually Guillaume, erroneously “Georges” (Brussels 1830–Brussels after 1909). Lithographer at the Royal Academy of Belgium, also a printer. He was especially renowned for his numerous plates of flowers, working to illustrate books as well as journals. In 1828 his father Guillaume Michel Corneille S. (Anvers 1804–Saint-Josse-Ten-Noode 1865) had founded in Brussels, Rue de Schuddebeek, a workshop of lithography and chromolithography, which employed up to thirty workers. Father and son are often mixed, because both signed as “G. Severeyns” (the son's manuscript signature was “G. Severeyns fils”), and it is almost impossible to precisely identify the participation of each one to the chromolithographies made during the years 1850–1865.

Terrier, Jules Laurent (Paris 1853–Paris 1927). Drawer, lithographer, engraver of woodcuts; as sculptor, pupil of Pierre Louis Rouillard (1820–1881) and Emmanuel Frémiet (1824–1910); also a taxidermist. From 1875, he was Assistant at the laboratory of Mammals and Birds at the “Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle”, and later chief of the taxidermy workshop; he introduced the use of the moulding plaster in stuffing. Among other dwellings, he successively lived in the two streets bordering the “Jardin des Plantes”, Rue Cuvier and then Rue Buffon. In 1903 he was portrayed by Henry Coëylas on the famous canvas “Reconstitution du Dodo ou Dronte à l’Atelier de Taxidermie du Muséum” (http://www.photo.rmn.fr/archive/14-546676-2C6NU0AGEM48Y.html). In 1909 he was nominated “Officier des Palmes Académiques”. Today he is mainly renowned by his bronze sculptures of animals.