The continental turtle fauna of Mexico is composed of 7 families, 13 genera, and 45 species; when subspecies are included, a total of 61 distinct taxa are recognized. We searched for the imperiled level or protection status of each taxon according to the IUCN Red List, CITES appendices, the 25 most endangered freshwater turtles and tortoises, and the protection lists issued by the Mexican Government. We explored the overlap of conservation status between Mexican and international agencies by comparing listing status. Among the 61 taxa, 37 were in the IUCN Red List, 16 taxa were listed on CITES appendices, 39 taxa were in NOM-059 (Mexican Government list), 4 taxa were in Conabio's list (Mexican Government list), and only 1 species was included in the world's 25 most endangered freshwater turtles and tortoises. The Central American river turtle (Dermatemys mawii), the desert tortoises (Gopherus spp.) and the black soft shell turtle (Apalone atra) were the only taxa included in all the lists surveyed. Our comparison of the lists indicates that at least 25 taxa of Mexican turtles are lacking basic information and require further study to inform their comprehensive conservation status. Further, we detected a noteworthy discrepancy between international and Mexican conservation priorities for turtle conservation.

Las tortugas continentales de México están compuestas por 7 familias, 13 géneros y 45 especies. Contando a las subespecies es posible distinguir un total de 61 taxa. En este trabajo buscamos el estatus de conservación o el grado de amenaza para cada taxón en la Lista Roja de la IUCN, los apéndices de CITES, las 25 especies de tortugas de agua dulce y terrestre más amenazas, así como las listas de protección de especies generadas por el Gobierno de México. Exploramos la superposición de los estatus de conservación entre las listas, y de los 61 taxa, 37 se incluyen en la Lista Roja de la IUCN, 16 taxa están incluidos en algún apéndice de CITES, 39 en la NOM-059, 4 en la lista de especies prioritarias de Conabio y solo uno lo está en la lista de las 25 especies de tortugas más amenazadas en el mundo. La tortuga blanca (Dermatemys mawii), las tortugas terrestres (Gopherus spp.) y la tortuga de concha blanda de Cuatrociénegas (Apalone atra) fueron los únicos taxa incluidas en todas las listas revisadas. Nuestra comparación entre listas indica que por lo menos 25 taxa de tortugas mexicanas carecen de la información necesaria para tener una idea clara de su estado de conservación, además, detectamos una discrepancia significativa entre las prioridades de conservación internacionales y las de México.

Chelonians are among the most endangered clades of vertebrates in the world (Böhm et al., 2013; Primack, 2012; Rhodin et al., 2011). There is no other reptile clade that includes as high a proportion of families and genera in endangered categories (Böhm et al., 2013), although chelonians are not as species-rich as lepidosaurians (Fritz & Havas, 2013). Even though the main conservation threats to turtles differ between taxa and regions of the world, general global hotspots for conservation challenges could be detected (van Dijk, Iverson, Rhodin, Shaffer, & Bour, 2014). Around the world, the most important threats for turtle populations are habitat loss, habitat degradation, poaching, introduced species, and subsidized predators (Klemens, 2000). For the Southeastern Asia hotspot, for instance, poaching and commercial trade have been the main factors reducing turtle populations. In other regions of the world such as the Americas, habitat loss plus habitat degradation are the main factors in turtle population reduction.

International efforts to create task forces such as the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, the Turtle Conservation Fund, and the Turtle Survival Alliance, have been undertaken in order to prevent turtle declines (Rhodin et al., 2011); however, country laws and concurrent public policies on species protection, conservation plans, and local trade regulations differ greatly between countries and even differ between states, provinces, and other levels of government. One consequence of these issues is threatened species and their associated conservation problems are attached to the jurisdictional and legal administration within countries, states, municipalities, counties, districts, etc. (Primack, 2012). In other words, conservation of species has become a government problem rather than merely a biological issue.

Mexico has the greatest reptile species richness in the Americas, and second worldwide (Conabio, 2008; Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014). Also it has the second-richest turtle fauna in the world after the U.S.A. (Legler & Vogt, 2013; van Dijk et al., 2014). The Mexican turtle (non-marine) fauna is composed of 7 families, 13 genera, and 45 species with at least 31 recognized subspecies – considered to be geographic variants (sensuWilson & Brown, 1953). All together, species and subspecies compose a block of 61 taxa (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014; Legler & Vogt, 2013; van Dijk et al., 2014). Fifty-seven percent of these taxa (35) are endemic and the probabilities remain high for potential new discoveries or upgrades from subspecies to species (Flores-Villela & García-Vázquez, 2014). The knowledge of natural history, ecology, and systematics of Mexican turtles is still incomplete (Iverson, Le, & Ingram, 2013) and Legler and Vogt (2013) have observed that more research is needed to increase the knowledge of life history of Mexican turtles in order to solve conservation problems.

Biodiversity conservation in Mexico is primarily the jurisdiction of the Federal Government. Mexican government agencies such as Semarnat (Ministry for Environment and Natural Resources), Conabio (National Commission for the Study of Biodiversity – a scientific authority), Profepa (Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection), Inecc (National Institute of Ecology and Climatic Change – a scientific authority and policy maker), CNF (National Commission of Forestry), and DGVS (General Directorate of Wildlife – part of Semarnat, and in charge of regulating wildlife management and game) are in charge of listing threatened species, protecting the listed species, designing and developing conservation programs for native species, and removing introduced species (Semarnat, 2014). Many of these agencies work under the Semarnat agenda (the higher-level agency and part of the executive government); however, internal agendas, lack of communication between agencies, and the frequent political and electoral uses of governmental programs within the Federal Government in Mexico limits conservation efforts and the allocation of financial resources for conservation (Mathews, 2014; Possingham et al., 2002).

According to international agreements signed by Mexico in environmental affairs, the threatened turtles of Mexico could be included in five lists/acts of imperiled species: NOM-059-Semarnat-2010 (NOM-059 from now), a list issued by the Federal Government (Semarnat, 2010) based on the Extinction Risk Manual (MER in Spanish), which generates individual profiles of species with data on distribution, demography, threats, and records. A call for papers is issued periodically for scholars, non-profit organizations, and research institutions to submit proposals for species to be included in the list. This list was first issued in 1994 under Ernesto Zedillo's government; since then, at least three updates have been published (Sedesol, 1994; Semarnat, 2001, 2010). The importance of NOM-059 for regional turtle conservation was discussed by Moll and Moll (2004, p. 268).

The Conabio List of Priority Species (Conabio, 2012) is another list issued by the Mexican government and is based upon a closed workshop of specialists from the federal government, academia, national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), international NGOs such as the IUCN, and private consultants (non-academics, but experts on conservation biology). The input data used for the Conabio list are official data (NOM-59, National System of Biological Information – SNIB).

The IUCN Red List (Red List from now), based on IUCN's own methodology (IUCN, 2001a); the CITES Appendices (CITES, 2013); and other lists such as the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group-Top 25+40 (which is based on the IUCN methodology with slight adjustments for chelonians) (Rhodin et al., 2011; van Dijk et al., 2014) also contribute to turtle protection. Among all of these lists, potential good conservation coverage should be predicted for Mexican turtles; however, there are some inquiries that should be made in order to know more about Mexican non-marine turtles’ conservation status.

In this paper we address these specific questions: (1) following Harris et al. (2012), do the imperiled species lists coincide/recognize with a minimum congruency of 70% (at least between the larger and general lists like the Red List and NOM-059)? If not, (2) what are the main discrepancies between the lists, and why? (3) What is the status of those particular species listed in all the threatened lists? (4) Are otherwise imperiled species (i.e., with confined geographic distributions or microendemism) not included in the lists? The answers to these questions should provide a clearer sense of whether including species on imperiled species lists (i.e., Red List, Endangered Species Act, Species at Risk Act) really works as a conservation strategy, and should contribute to the debate about how well listing species on imperiled species lists works to protect biodiversity in emerging democracies like Mexico (Harris et al., 2012; Possingham et al., 2002).

Materials and methodsWe compiled a comprehensive list of the species of freshwater turtles and tortoises naturally occurring in Mexico based on recognized taxa published in Flores-Villela and Canseco-Márquez (2004), Flores-Villela and García-Vázquez (2014), Legler and Vogt (2013), Liner and Casas-Andreu (2008), and van Dijk et al. (2014). We double checked each taxon's conservation status on the Red List, the Appendices of CITES, the NOM-059, Conabio's list, the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group list (top 25+other 40 species), and in the Wilson, Mata-Silva, and Johnson (2013) adapted Environmental Vulnerability Score (EVS) for the reptiles of Mexico as an additional list (non-official and non-NGO list).

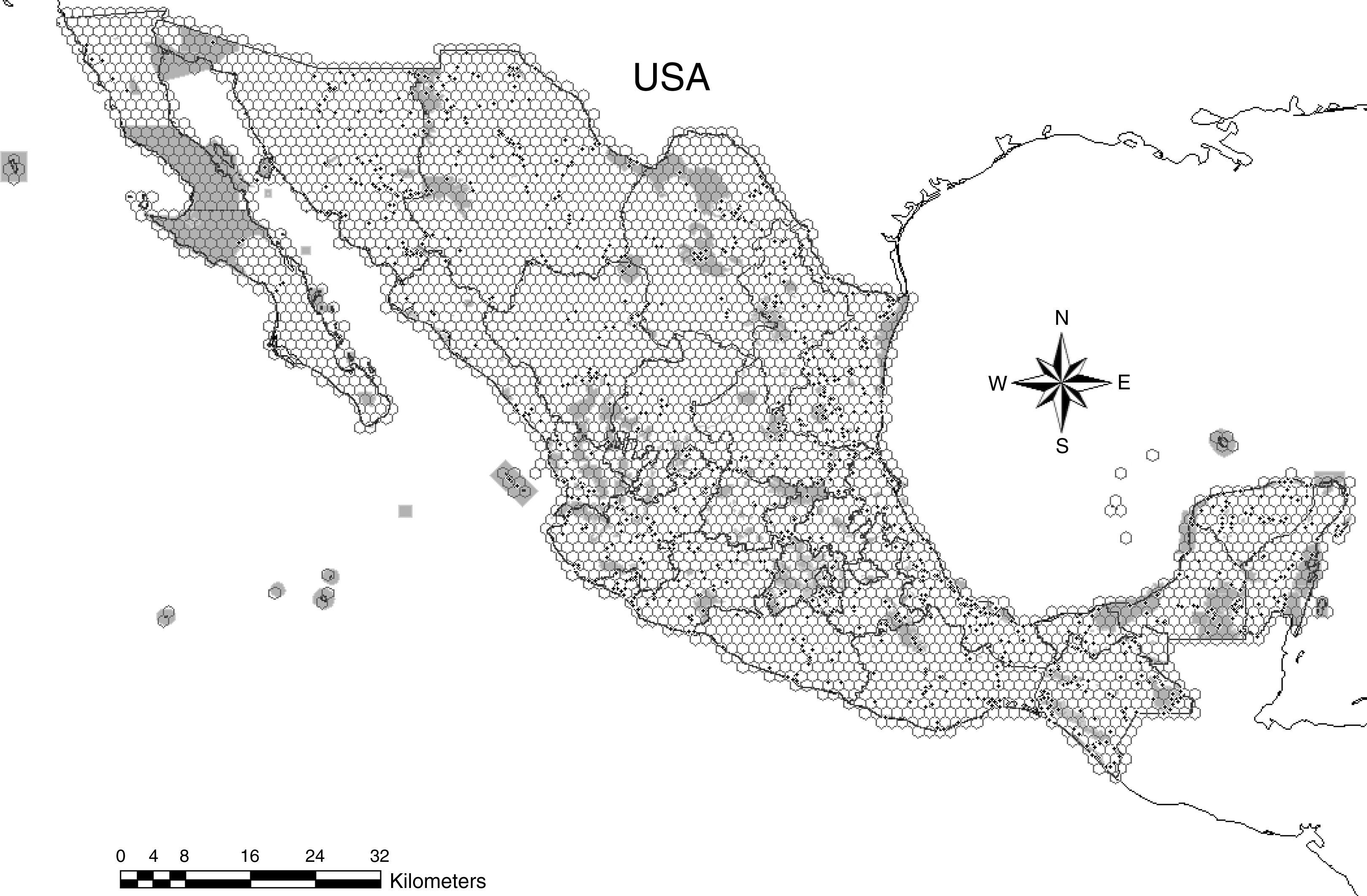

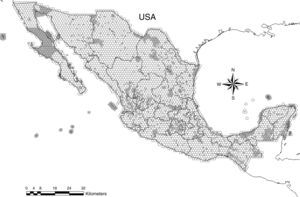

We included each threat category in our database and also recorded whether or not each species was endemic to Mexico. To gather and analyze geographic information in order to determine the geographic distribution of each taxon, we used the official records (available from the government) for all the turtles collected within Mexico. This information was used to estimate the distribution area. We follow Riddle, Ladle, Laurie, and Whittaker (2011), Terborgh and Winter (1983), and the IUCN (2001b) for the species area of occupancy delimitations and we distinguish the following categories: a threshold of 50,000–80,000km2 in which species were considered “restricted”, between 80,000 and 120,000km2 “widely distributed”. Below the 50,000km2 threshold, species were considered to be “micro-endemic”, with subdivisions of between 50,000 and 20,000km2 being a “confined distribution”, and between 20,000 and 5,000km2 considered as “marginally distributed”. Distribution records were provided by Conabio's National System of Biological Information (SNIB in Spanish; www.conabio.gob.mx).

The distribution records are official data (quality control checked by Conabio's professional staff) and came from museum records, research projects, and selected collections with Mexican specimens around the world. These records represent the public and official information used by Mexican federal authorities to design biological conservation policies and do not include other records like personal collections or databases. We decided to use only those records in order to follow what Mexican authorities should do for the protection of imperiled species in accord with the law currently.

We used ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI, 2012) to plot all the records of turtles on a map of Mexico. To sample and calculate the approximate species area of occupancy we used a grid of 1,267 hexagons with an area of 640km2 each. This area is quite similar to quadrants of 0.25×0.25 degrees. This scale approach has been suggested as a general protocol when studying species distribution (Riddle et al., 2011). Ochoa-Ochoa and Flores-Villela (2006) used a 0.5×0.5 degree for amphibians and reptiles of Mexico; Koleff and Soberón (2008) also used a 0.5×0.5 degree grid scale for an analysis of vertebrate diversity in Mexico. Recently, Ochoa-Ochoa, Campbell, and Flores-Villela (2014) tested for different scales in diversity and endemism for the herpetofauna of Mexico, and suggested that fine scales allow recognition of more precise biogeographic patterns.

To determine the area of occupancy categories, we sampled all of SNIB's records in the following way: A single point inside a hexagon was consider a taxon distributed throughout the entire hexagon, then the sum of all the hexagons with records was used as a proxy for the species’ distribution. We are aware that this approach could obscure disjunct distributions (Terborgh and Winter, 1983) and overestimate real distribution areas (i.e., near borders of the country or along seashore); however, the grid scale we used is considered fine enough to unmask precise distribution patterns (disjunct and natural gaps) and rather broad distribution areas (Ochoa-Ochoa et al., 2014). We also sum how many records fall in nature reserves (federal, state, and municipal) around the country.

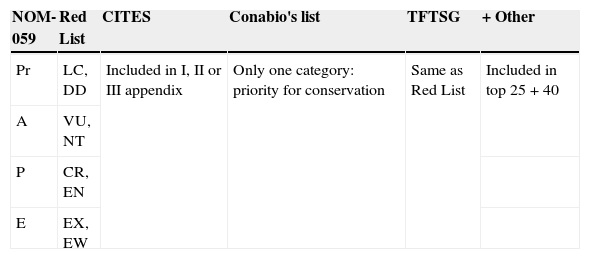

The most comparable lists were the Red List and the NOM-059. Threat category definitions are available elsewhere (IUCN, 2001b; Semarnat, 2010; on line at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories-and-criteria and http://www.profepa.gob.mx/innovaportal/file/435/1/NOM_059_SEMARNAT_2010.pdf). We reviewed each category and cluster them according to the definitions of threats for each category (IUCN, 2001b; Semarnat, 2010). Table 1 summarizes the equivalence of threats between the two lists.

Comparative categories between conservation lists: P=endangered (in danger of extinction); Pr=under special protection; A=threatened; LC=least concern; DD=data deficient; VU=vulnerable; NT=near threatened; CR=critically endangered; EN=endangered; EX=extinct; EW=extinct in the wild; CITES=conservation on international trade in endangered species of Wild Fauna and Flora; TSTSG=Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group of the IUCN; Top 25+40=is a list issued by the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group of the IUCN which contains the world's 25 most endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles, plus other top 40 tortoises and freshwater turtles at very risk of extinction; Conabio's list=a list of the species consider for conservation priority, issued by the National Commission for the Study of Biodiversity (a Mexican Federal Government scientific agency); NOM-059=list of Mexican protected species of flora and fauna by federal government.

| NOM-059 | Red List | CITES | Conabio's list | TFTSG | +Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr | LC, DD | Included in I, II or III appendix | Only one category: priority for conservation | Same as Red List | Included in top 25+40 |

| A | VU, NT | ||||

| P | CR, EN | ||||

| E | EX, EW |

We looked for a minimum of 70% congruency between the comparable lists (NOM-059 and Red List). We set that percentage based on the finding of Harris et al. (2012) that on average 74% under recognition between the species included in the IUCN Red List and the species included in the Endangered Species Act of the United States of America for six animal lineages. We approach the issue with a quantitative method using a contingency table, followed by a correspondence analysis (Sokal & Rohlf, 2012). We used JMP (SAS Institute Inc, 2002) for statistical analyses with an α=0.05. We also generate a categorization of threats based on the presence of species in all the survey lists, ‘5 lists’, ‘4 lists’, ‘3 lists’, and ‘2 lists’ in conjunction with their distribution range within the country. In each case we suggest whether the status of the species should be revised/revisited or clarified in cases of obvious discordances.

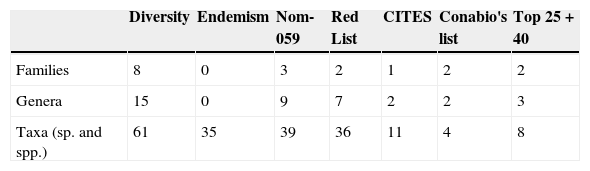

ResultsWe compiled a list of 61 taxa including species and subspecies, of which 35 taxa (57%) were endemic to Mexico. The NOM-059 included 39 taxa (64% of all taxa), the Red List included 37 taxa (60%), 17 (26%) were included in CITES appendices, 4 (6.5%) in Conabio's list, and 8 taxa (13%) in the TFTSG list. The mean score for Wilson's EVS was 15.3 (20 is the maximum possible value), ranging from 8 to 20, but we find 12 of 39 species (30.8%) with scores above 18 (no subspecies level was used by Wilson et al., 2013) (Table 2). Based on the 4,093 records provided by Conabio's SNIB (Fig. 1), the area of occupancy categories only included two taxa (Kinosternon integrum, Trachemys venusta venusta) as widely distributed; 10 taxa showed a restricted distribution, 24 taxa showed a confined distribution, 16 taxa showed a marginal distribution, and no data were available for 8 taxa (Table 3). The ranges of 39 taxa (64%) fall within a nature reserve, including some important species like the four species of tortoises, Dermatemys mawii, all box turtles, 3 wood turtles, 14 mud turtles, 2 soft-shell turtles, 1 chelydrid, and 5 sliders (Fig. 1).

Mexican non-marine turtle diversity, endemism, and the number of taxa included in the conservation lists issued to 2013. CITES=conservation on international trade in endangered species of Wild Fauna and Flora; TSTSG=Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles Specialist Group of the IUCN; Top 25+40=is a list issued by the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group of the IUCN which contains the world's 25 most endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles, plus other top 40 tortoises and freshwater turtles at very risk of extinction; Conabio's list=a list of the species consider for conservation priority, issued by the National Commission for the Study of Biodiversity (a Mexican Federal Government scientific agency); NOM-059=list of Mexican protected species of flora and fauna by federal government.

| Diversity | Endemism | Nom-059 | Red List | CITES | Conabio's list | Top 25+40 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families | 8 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Genera | 15 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Taxa (sp. and spp.) | 61 | 35 | 39 | 36 | 11 | 4 | 8 |

Records of the freshwater turtles and tortoises (dots) provided by the National Commission for Knowledge and Conservation of the Biodiversity's (Conabio) National System of Biological Information (SNIB). Hexagons represent our sample unit. Each hexagon contains 640km2. The areas shaded in gray represent the nature reserves of Mexico.

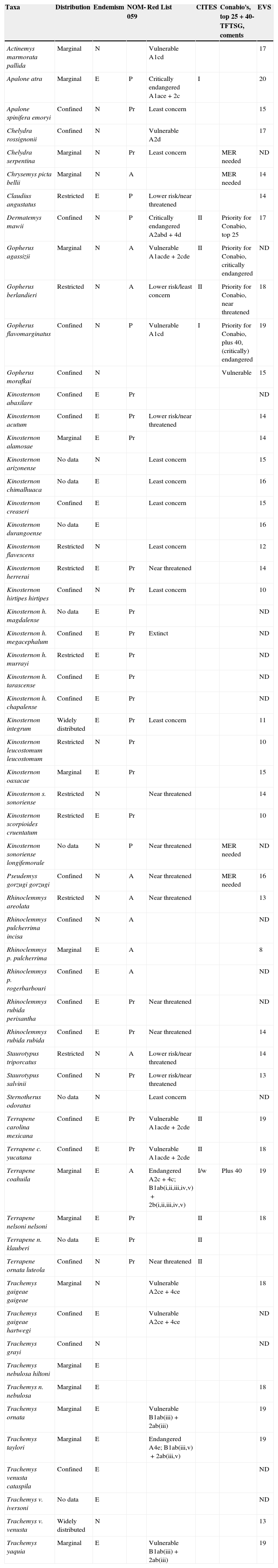

Complete list of freshwater and terrestrial turtle taxa from Mexico. N=not endemic, E=endemic; P=endangered (in danger of extinction), Pr=under special protection, A=threatened; MER needed=risk evaluation methods needed; EVS=Environmental Vulnerability Score for Mexican turtles (from Wilson et al., 2013); CITES=conservation on international trade in endangered species of Wild Fauna and Flora; TSTSG=Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles Specialist Group of the IUCN; Top 25+40=is a list issued by the Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group of the IUCN which contains the world's 25 most endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles, plus another 40 tortoises and freshwater turtles at very high risk of extinction; Conabio's list=a list of the species considered a conservation priority, issued by the National Commission for the Study of Biodiversity (a Mexican Federal Government scientific agency); NOM-059=list of Mexican protected species of flora and fauna by federal government; EVS=Environmental Vulnerability Score (Wilson et al., 2013); ND=No Data.

| Taxa | Distribution | Endemism | NOM-059 | Red List | CITES | Conabio's, top 25+40-TFTSG, coments | EVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinemys marmorata pallida | Marginal | N | Vulnerable A1cd | 17 | |||

| Apalone atra | Marginal | E | P | Critically endangered A1ace+2c | I | 20 | |

| Apalone spinifera emoryi | Confined | N | Pr | Least concern | 15 | ||

| Chelydra rossignonii | Confined | N | Vulnerable A2d | 17 | |||

| Chelydra serpentina | Marginal | N | Pr | Least concern | MER needed | ND | |

| Chrysemys picta bellii | Marginal | N | A | MER needed | 14 | ||

| Claudius angustatus | Restricted | E | P | Lower risk/near threatened | 14 | ||

| Dermatemys mawii | Confined | N | P | Critically endangered A2abd+4d | II | Priority for Conabio, top 25 | 17 |

| Gopherus agassizii | Marginal | N | A | Vulnerable A1acde+2cde | II | Priority for Conabio, critically endangered | ND |

| Gopherus berlandieri | Restricted | N | A | Lower risk/least concern | II | Priority for Conabio, near threatened | 18 |

| Gopherus flavomarginatus | Confined | N | P | Vulnerable A1cd | I | Priority for Conabio, plus 40, (critically) endangered | 19 |

| Gopherus morafkai | Confined | N | Vulnerable | 15 | |||

| Kinosternon abaxilare | Confined | E | Pr | ND | |||

| Kinosternon acutum | Confined | E | Pr | Lower risk/near threatened | 14 | ||

| Kinosternon alamosae | Marginal | E | Pr | 14 | |||

| Kinosternon arizonense | No data | N | Least concern | 15 | |||

| Kinosternon chimalhuaca | No data | E | Least concern | 16 | |||

| Kinosternon creaseri | Confined | E | Least concern | 15 | |||

| Kinosternon durangoense | No data | E | 16 | ||||

| Kinosternon flavescens | Restricted | N | Least concern | 12 | |||

| Kinosternon herrerai | Restricted | E | Pr | Near threatened | 14 | ||

| Kinosternon hirtipes hirtipes | Confined | N | Pr | Least concern | 10 | ||

| Kinosternon h. magdalense | No data | E | Pr | ND | |||

| Kinosternon h. megacephalum | Confined | E | Pr | Extinct | ND | ||

| Kinosternon h. murrayi | Restricted | E | Pr | ND | |||

| Kinosternon h. tarascense | Confined | E | Pr | ND | |||

| Kinosternon h. chapalense | Confined | E | Pr | ND | |||

| Kinosternon integrum | Widely distributed | E | Pr | Least concern | 11 | ||

| Kinosternon leucostomum leucostomum | Restricted | N | Pr | 10 | |||

| Kinosternon oaxacae | Marginal | E | Pr | 15 | |||

| Kinosternon s. sonoriense | Restricted | N | Near threatened | 14 | |||

| Kinosternon scorpioides cruentatum | Restricted | E | Pr | 10 | |||

| Kinosternon sonoriense longifemorale | No data | N | P | Near threatened | MER needed | ND | |

| Pseudemys gorzugi gorzugi | Confined | N | A | Near threatened | MER needed | 16 | |

| Rhinoclemmys areolata | Restricted | N | A | Near threatened | 13 | ||

| Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima incisa | Confined | N | A | ND | |||

| Rhinoclemmys p. pulcherrima | Marginal | E | A | 8 | |||

| Rhinoclemmys p. rogerbarbouri | Confined | E | A | ND | |||

| Rhinoclemmys rubida perixantha | Confined | E | Pr | Near threatened | ND | ||

| Rhinoclemmys rubida rubida | Confined | E | Pr | Near threatened | 14 | ||

| Staurotypus triporcatus | Restricted | N | A | Lower risk/near threatened | 14 | ||

| Staurotypus salvinii | Confined | N | Pr | Lower risk/near threatened | 13 | ||

| Sternotherus odoratus | No data | N | Least concern | ND | |||

| Terrapene carolina mexicana | Confined | E | Pr | Vulnerable A1acde+2cde | II | 19 | |

| Terrapene c. yucatana | Confined | E | Pr | Vulnerable A1acde+2cde | II | 18 | |

| Terrapene coahuila | Marginal | E | A | Endangered A2c+4c; B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v)+2b(i,ii,iii,iv,v) | I/w | Plus 40 | 19 |

| Terrapene nelsoni nelsoni | Marginal | E | Pr | II | 18 | ||

| Terrapene n. klauberi | No data | E | Pr | II | |||

| Terrapene ornata luteola | Confined | N | Pr | Near threatened | II | ||

| Trachemys gaigeae gaigeae | Marginal | N | Vulnerable A2ce+4ce | 18 | |||

| Trachemys gaigeae hartwegi | Confined | E | Vulnerable A2ce+4ce | ND | |||

| Trachemys grayi | Confined | N | ND | ||||

| Trachemys nebulosa hiltoni | Marginal | E | |||||

| Trachemys n. nebulosa | Marginal | E | 18 | ||||

| Trachemys ornata | Marginal | E | Vulnerable B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) | 19 | |||

| Trachemys taylori | Marginal | E | Endangered A4e; B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v) | 19 | |||

| Trachemys venusta cataspila | Confined | E | ND | ||||

| Trachemys v. iversoni | No data | E | ND | ||||

| Trachemys v. venusta | Widely distributed | N | 13 | ||||

| Trachemys yaquia | Marginal | E | Vulnerable B1ab(iii)+2ab(iii) | 19 |

From the 39 taxa included in the NOM-059, 24 were in category Pr, 10 listed as A, and 5 taxa listed as P. The 37 taxa included in the Red List were distributed as follows: 10 taxa least concern, 12 near threatened, 2 endangered, 10 vulnerable, 2 critically endangered, and 1 extinct. Following our comparison between lists, the congruency between NOM-059 and the Red List was around 44%. Contingency table analysis did not reveal any statistical association between the two lists (χ232=9.96, p=0.44). Even when the correspondence analyses were conducted (besides the non-significant result of the contingency table), we only found a partial congruency between those species listed in Under Special Protection (Pr) category by the NOM-059 and the Least Concern (LC) category of the Red List. Nevertheless these two categories are not necessarily analogous (see Semarnat, 2010; IUCN, 2013). In short, the under recognition of both lists was around 56%.

The Central American river turtle (D. mawii) and the black spiny softshell (Apalone atra, but see Cerdá-Ardura, Soberón-Mobarak, McGaugh, and Vogt for taxonomic uncertainty and historical conservation status) were the only two taxa included in all the lists reviewed under the highest threat. Dermatemys mawii is considered a priority for the Mexican Government and the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group considers it at extremely high risk of extinction (Rhodin et al., 2011), but A. atra is considered P in NOM-059 since 2010, and is included on Appendix I by CITES, but is not included as a priority species for the Mexican government; however, since it is found in Cuatrociénegas with its serious conservation problems it is somehow considered protected. Mexican desert tortoises, including Gopherus agassizii now restricted to the United States, but with an isolated population in Baja California Sur (Murphy et al., 2011), was also included in all the lists we reviewed with status ranging from Least Concern to Endangered or Vulnerable (Red List). The three recognized Mexican tortoises are also considered a priority for conservation by the Mexican government, but only G. flavomarginatus is included in the ‘other 40 top tortoises and freshwater turtles at very high risk of extinction’ issued by the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (Rhodin et al., 2011). There are no data available about G. morafkai; however, former conservation problems of Gopherus agassizii should be imputable due to the species’ recent taxonomic update (Murphy et al., 2011). The Yucatán box turtle (Terrapene carolina yucatana) and narrow-bridged musk turtle (Claudius angustatus) were both included on the Red List, NOM-059, and CITES, ranging from Near Threatened to Endangered.

Data about protection of endemic taxa with microendemic distributions (see Table 3), like Trachemys nebulosa sspp., Trachemys venusta sspp., and Kinosternon durangoense were absent from all the lists surveyed. Other endemic species like Creaser's mud turtle (K. creaseri) and Kinosternon chimalhuaca were only considered under the Least Concern category by the Red List, but no further information was available in other lists. Gopherus morafkai and K. arizonense were also absent from all the lists surveyed. A series of other species were contained only in one of the lists (i.e., under special protection in NOM-059; Table 3).

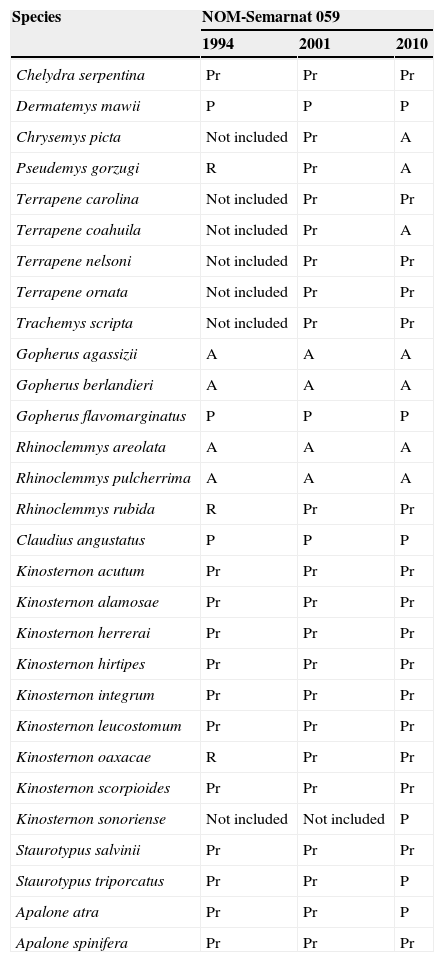

There is a group of species missing in the NOM-059 for several reasons (i.e., ignorance of their occurrence in Mexico and/or taxonomic updates). We tracked the NOM-059 over the three past versions to the species level only because of the lack of subspecies availability data in the previous issues (Sedesol, 1994; Semarnat, 2001, 2010) and the number of species included changed slightly from 23 in 1994, to 28 in 2001, and to 29 in 2010. Most of the increase corresponds with the inclusion of the genus Terrapene and to other taxonomic updates to the list. The NOM-059 also changed from 1994 to 2010 in the number of species under specific threat categories (Table 4). In 1994, 13 species were under Pr, 3 were threatened (A), 3 under extinction risk (P), and 3 under rare (R, but this category is no longer in use in the NOM-059); in 2001, 21 species were under Pr, 4 under A, and 3 under P; finally in 2010, 16 species were under Pr, 7 under A, and 6 under P. That means that the number of species under special protection increased 61% from 1994 to 2001 and then was reduced by 24% in 2010. Most dramatically, endangered species (‘A’ category) increased 75% from 1994 to 2010, while extinction risk category species increased 100% from 1994 to 2010 (Table 4).

Progression in the conservation status of Mexican freshwater turtles and tortoises from the first year NOM-059 was issued (1994) to the last list issued in 2010. P=endangered (of extinction), Pr=under special protection, A=threatened, R=rare (no longer in use).

| Species | NOM-Semarnat 059 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 2001 | 2010 | |

| Chelydra serpentina | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Dermatemys mawii | P | P | P |

| Chrysemys picta | Not included | Pr | A |

| Pseudemys gorzugi | R | Pr | A |

| Terrapene carolina | Not included | Pr | Pr |

| Terrapene coahuila | Not included | Pr | A |

| Terrapene nelsoni | Not included | Pr | Pr |

| Terrapene ornata | Not included | Pr | Pr |

| Trachemys scripta | Not included | Pr | Pr |

| Gopherus agassizii | A | A | A |

| Gopherus berlandieri | A | A | A |

| Gopherus flavomarginatus | P | P | P |

| Rhinoclemmys areolata | A | A | A |

| Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima | A | A | A |

| Rhinoclemmys rubida | R | Pr | Pr |

| Claudius angustatus | P | P | P |

| Kinosternon acutum | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon alamosae | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon herrerai | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon hirtipes | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon integrum | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon leucostomum | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon oaxacae | R | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon scorpioides | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Kinosternon sonoriense | Not included | Not included | P |

| Staurotypus salvinii | Pr | Pr | Pr |

| Staurotypus triporcatus | Pr | Pr | P |

| Apalone atra | Pr | Pr | P |

| Apalone spinifera | Pr | Pr | Pr |

The lack of concordance between the lists issued by the Mexican Government and those issued by international NGO's and specialist groups such as the IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group is based on the disarticulation of the Mexican public administration, from the data available to the decision-making process. As a general trend, the NOM-059 generally lacks the taxa included in the Red List, meanwhile the Red List is also lacking taxa that should be included according to their status in the NOM-059 and their distribution ranges (Table 3). This situation merits the following questions: What is the logic of international cooperation agreements on conservation biology if the information exchange is not consistent or even ignored? What are the missing links between the use of databases such Conabio's SNIB and the decision-making process?

Most of the under recognition between lists is related to misunderstandings (probably ignorance or lack of information) and a very slow information update process between official lists issued by Mexican Government agencies and the international lists (generally issued by specialist groups). There is also an imperfect understanding of international differences in the protocols for listing species. Vague definitions of some risk categories such as ‘threatened’ (A),‘endangered’ (P), ‘under special protection’ (Pr), and the difference in the primary function of the assessment lists and their association with local laws (Harris et al., 2012; Hutchings & Festa-Bianchet, 2009; Possingham et al., 2002) could drive the various lists to profound incongruences. Another problem, such as the lack of professionalization of government agencies like those of emerging economies such as Mexico, could break the flow of information about new species and taxonomic changes of the involved taxa. Most of the time, conservation, taxonomic, and distributional data updates reach the people in charge of updating the lists and the decision makers with considerable delay.

Based on our list comparisons it is hard to affirm which have it right and which have it wrong, being the international agencies or the Mexican government. It is also hard to tell if the difficult work has been done by the international agencies or by Mexican agencies? Certainly both succeed and fail, but the confusion generated by the lack of concordance makes conservation efforts difficult. We believe that at least the following species should be evaluated for their inclusion in the NOM-059 due to the precedent of the species already included: the Nazas slider (Trachemys gaigeae hartwegi), T. ornata, T. taylori, and T. yaquia. They could be included in the Pr category since they are endemic with small areas of occupancy (<50,000km2 or microendemic) within the country (Legler & Vogt, 2013; this paper). Kinosternon chimalhuaca, K. durangoense, and Cryptochelys creaseri also should be included in the Pr category because they are endemic, confined to a small portion on the coast of Jalisco (Berry, Seidel, & Iverson, 1997), the Mapimí Basin in Durango (Legler & Vogt, 2013), and the Yucatán Peninsula (Iverson, 1988), respectively. Official data about their distribution are available in Conabio's SNIB database. Finally, the recent upgrade to species level of Gopherus morafkai (Murphy et al., 2011) involves transferring the previous conservation status of G. agassizii in Mexico (Semarnat, 2010) to the newly recognized G. morafkai, but this issue exposes the following question: is it necessary to add a new category for recent discovered or named species? The answer to that question certainly needs careful thought.

On the other hand, the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group should review or consider updating the status of the following: painted wood turtle (Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima) (A category under Mexican law, NOM-059); R. p. incisa (A category on NOM-059); R. p. rogerbarbouri (A category on NOM-059); K. chimalhuaca (Pr category on NOM-059, but with an extremely reduced distribution range, see Table 3); K. abaxillare (recently upgraded to species status and with an extremely reduced distribution range; Iverson et al., 2013); and the subspecies of hirtipes (K. h. megacephalum, K. h. murrayi, K. h. magdalense, K. h. chapalaense, and K. h. tarascense) as one is considered extinct and the other listed as Pr. These K. hirtipes subspecies should be considered because of their rarity, reduced distribution range, and the conservation problems of their natural habitat in the states of Michoacán and Jalisco (Reyes-Velasco, Iverson, & Flores-Villela, 2013). The Red List recognizes subspecific taxonomic levels, but for Mexican turtles they are included only for few taxa.

More research and data are needed on Kinosternon oaxacae, K. alamosae, Trachemys n. nebulosa, T. n. hiltoni, Terrapene n. nelsoni, and T. n. klauberi. All of these taxa are endemic with marginal to very restricted distribution areas. They have a minimum level of protection; however, more data are needed in order to understand the conservation and demographic status of their populations.

Besides D. mawii and the genus Gopherus, the following taxa should be considered as a priority for conservation in the country: Terrapene carolina yucatana, which is very rare and difficult to find in the wild (Jones et al., unpublished data) and it inhabits an area rapidly losing its natural habitat. This species is considered Vulnerable A1acde+2cde by the Red List, Pr in NOM-059, and included in Appendix II of CITES; Terrapene coahuila is surviving under the severe conservation problems in Cuatrociénegas (Contreras-Balderas, 1984; Semarnat, 1991), and is considered Endangered A2c+4c; B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v)+2b(i,ii,iii,iv,v) by the Red List, also included in CITES Appendix I/W, and in the “other 40” list. Trachemys taylori also inhabits Cuatrociénegas with its conservation problems (Contreras-Balderas, 1984; Semarnat, 1991), and is considered Endangered A4e; B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v)) by the Red List. Apalone atra, another species inhabiting Cuatrociénegas (Contreras-Balderas, 1984; Semarnat, 1991), is considered Critically Endangered A1ace+2c by the Red List, endemic, and is found under the P category of NOM-059. Finally, Claudius angustatus, a highly consumed turtle in southeastern Mexico is listed under the P category of NOM-059, and is considered at Lower Risk/near threatened by the Red List. This species has much the same conservation problems as the Mexican tortoises; however, it has been omitted in Conabio's list of priority species.

The results generated in this paper expose several concerns about turtle conservation biology in Mexico (and probably in other lineages). First, there is a lack of correspondence between Red List and NOM-059 status; both lists should be concordant if the conservation policies followed by the Federal Government are to be in accord with international agreements and the conservation strategies and public policies on threatened species. The discrepancy of the conservation status between lists seriously complicates and limits conservation efforts (Soulé & Orians, 2001). Examples from trees (FAO, 2006), polar bears (Hutchings & Festa-Bianchet, 2009), birds (Harris et al., 2012), and current studies on turtles from Colombia (Forero-Medina, Páez, Garcés-Restrepo, Carr, & Giraldo, in press) document a generalized problem. Actually, the under recognition percentage between lists we found (56%) are quite similar to other animals in similar studies (Harris et al., 2012). Second, the lack of a herpetological specialist group in Mexico that collaborates with the Federal Government (or any other government level) on conservation issues contrasts with the regular practice of other countries and governments, in which specialist groups, policy makers, stakeholders, land owners, and civil society work collaboratively together to solve conservation issues (Primack, 2012). Due to the size, high biodiversity, and sociocultural complexity of Mexico, it is reasonable that Conabio, Semarnat, Profepa, INECC, and other government agencies do not have a comprehensive and trained staff to deal with all the conservation problems; however, this is not acceptable in the supposed 11th economy of the world. Third, so far there are no quantitative results derived from the public policies on the conservation of non-marine turtles in Mexico. The only data lie in the slight change in the number of species included in the list and the number of species that changed to threatened or in extinction risk from 1994 to 2010. This indicates that a strategy for conservation of freshwater turtles and tortoises is nonexistent or has never been conceived. Compared with other vertebrates such as crocodiles, sea turtles, raptors, parrots, and mammals, freshwater turtles and tortoises have been ignored by conservation efforts in Mexico (Conabio, 2008).

The conservation of non-marine turtles in Mexico should be carefully revised and revisited. A main goal should be to improve the congruence between the threatened categories of international and local lists, in order to meet obligations to focus research, funds, budgets, and other political efforts toward generating a benchmark of protection for such a diverse group of reptiles in the country. Since the Red List is not a regulatory apparatus, local lists such NOM-059 should be strengthened (empowered) to become a comprehensive, systematic assessment that could interact with its counterparts, such as the Endangered Species Act in the case of the shared fauna between Mexico and the U. S., however listing imperiled species should be used as a conservation tool and not only to document environmental degradation. One bit of good news is that at least 64% of the taxa occur in protected land, which includes federal, state, and municipal nature reserves.

Funding for this project was granted by Programa del Mejoramiento del Profesorado (SEP-Promep PROMEP/103.5/12/4367) and the Vicerrectoría de Estudios de Posgrado of the Benémerita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (VIEP-BUAP VIEP-2014-155). We want to thank John Legler and Richard Vogt for inviting us to the Symposium on Mexican Turtles at the 11th Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) meeting, at which the original ideas for this paper were presented and discussed in an early stage. TSA generously support RMR with a travel grant to present preliminary results. Griselda Jorge Lara helped with species distribution analysis. We want to thank Michael T. Jones for his stimulating comments on early drafts and to John L. Carr for comments on an advanced draft. Several anonymous reviewers made relevant comments on early versions of this manuscript. Finally, we thank J. Rogelio Cedeño Vázquez for the follow-up during the editorial process.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.