We recorded a population of Military Macaws in the community of Salazares, Nayarit, Mexico. The observations were made in 2 sites, the Pilas and Mirador del Aguila; both sites have vegetation of tropical semi-deciduous forest with trees of 8–28m high with a diameter at breast height greater to 40cm. The objective of this study was to describe the activities of the Military Macaw, as well as the use of the cavities presents at cliff and trees. For 5 years of non-continuous counts, we recorded 43.5±2.6 individual encounters; most records were made in the morning. Reproductive activity was also observed in the tree cavities (n=1), and in the cliff ones (n=1). Nine cavities were also recorded that served for roosting. This species record is important because it provides information about the existence of a breeding population in central Nayarit. We suggest working with the community and encourage efforts to make the zone a natural protected area.

Se registró una población de guacamaya verde en la comunidad de Salazares, Nayarit, México. Las observaciones se realizaron en 2 sitios, las Pilas y el Mirador del Águila; ambos tienen la vegetación del bosque tropical semideciduo con árboles de 8 a 28m de altura con un diámetro a la altura del pecho mayor de 40cm. El objetivo de este estudio fue describir las actividades realizadas por la guacamaya verde, así como también el uso de las cavidades presentes en el acantilado y los árboles. Durante 5 años de conteos no continuos, se registraron 43.5±2.6 encuentros individuales; la mayoría de los registros se realizaron en la mañana. También se observó la actividad reproductiva en las cavidades de los árboles (n=1) y del acantilado (n=1). Se registraron 9 cavidades que sirvieron como dormitorios. Este registro de la especie es importante ya que proporciona información sobre la existencia de una población reproductora en el centro de Nayarit. Se aconseja trabajar con la comunidad y fomentar los esfuerzos para hacer de la zona un área natural protegida.

Macaws are a group of Psittacidae (Psittaciformes: Aves) exclusive to the American continent. In Mexico there are 2 species of macaws, Military Macaw (Ara militaris) and Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao). The Military Macaw is categorized as vulnerable worldwide (Cites, 1998; IUCN, 2014). Mexican law considers it an endangered species (Semarnat, 2010) due to the reduction of its populations caused by illegal trade and the fragmentation of its natural habitat (Ríos-Muñoz & Navarro-Sigüenza, 2009; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013).

The Military Macaw is closely associated with tropical deciduous forest and semi-deciduous forest, due to the relationship between availability of food resources and breeding sites that these forests provide (Collar & Juniper, 1992; Saunders, 1977; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013). Historically, this species nests in cavities of emergent trees or cliffs in hard-to-reach isolated areas (Íñigo-Elías, 1999; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013). Most observations report the species nesting in cavities in cliffs (Forshaw, 2010; Gaucín, 2000; Rivera-Ortíz, Contreras-González, Soberanes-González, Valiente-Banuet, & Arizmendi, 2008).

The sites where the Military Macaw nests in cliffs are characterized as being karst rock with tropical deciduous forest vegetation; the tree species present in these sites have a height of not more than 12m and a DBH of 5–35cm, so their nests can only be made in the cavities of the cliffs (De la Parra-Martínez, Renton, Salinas-Melgoza, & Muñoz-Lacy, 2015; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013). Unlike sites where the Military Macaw nests in trees, the vegetation is tropical semi-deciduous forest and this site has the structural characteristics required for nesting in trees, because in these places the trees have heights greater than 16m and DAPs of 67–205cm (Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013).

The breeding season of the Military Macaw in Mexico is varied. In northwest Mexico the breeding season is reported to take place from March to October (Forshaw, 2010; Nocedal, Sierra, & Arroyo, 2006; Rubio, Beltrán, Aviléz, Salomón, & Ibarra, 2007). The reproductive season in western Mexico, mainly on the coast of Jalisco, begins with the selection of nests from October to November and ends with the departure of juveniles between January and March (Carreón, 1997; De la Parra-Martínez et al., 2015). In central Mexico, the breeding season is from May to September, much like the sites in the northwest of the country (Gaucín, 2000; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008). Differences between reproduction seasons in Mexico are based on the phenology of tree species and resource availability (Íñigo-Elías, 1999).

The Military Macaw has a specialized diet composed mainly of seeds and fruits of a few plant species (Contreras-González, Rivera-Ortíz, Soberanes-González, Valiente-Banuet, & Arizmendi, 2009). The plant genera Bunchonsia, Hura, Lysiloma, and Bursera have been reported as important sources of food within the distribution of the Military Macaw in Mexico (Carreón, 1997; Contreras-González et al., 2009; Gaucín, 2000; Loza, 1997; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008, 2013). These plant species contain a large amount of nutrients, such as lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins, that are important for egg laying and the development of chicks (Contreras-González et al., 2009).

The distribution of the Military Macaw in Mexico is along the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre del Sur (Pacific slope) (Almazán-Núñez and Nova-Muñoz, 2009; Howell & Webb, 1995; Peterson & Chalif, 1989), in northeastern Mexico in the Sierra Madre Oriental (Gulf of Mexico slope) (Arizmendi & Márquez, 2000; Íñigo-Elías, 1999; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013), and in central Mexico (Hernández-Castán, Villordo-Galván, Canogarcía, Gaspariano-Martínez, & Rodríguez-Cantalapiedra, 2012; Jiménez-Arcos, Santa Cruz-Padilla, Escalona-López, Arizmendi, & Vázquez, 2012; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008; Urbina-Torres, Monroy-Vilchis, González-Martínez, Amador-Solís, & Celis-Murillo, 2012). However, in recent years its distribution has been drastically reduced by the change in land use and illegal trade (Marín-Togo et al., 2012; Monterrubio-Rico, Labrada-Hernández, Ortega-Rodríguez, Cancino-Murillo, & Villaseñor, 2010; Ríos-Muñoz & Navarro-Sigüenza, 2009; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013).

The Royal Botanical Expedition of New Spain published the first records of the Military Macaw from the Pacific coast between 1787 and 1803 (Navarro-Sigüenza, Peterson, Puig-Samper, & Zamudio, 2007). In the state of Nayarit, the Military Macaw has been registered in the Cañón del Oro (Velásquez-Noguerón et al., 1987), and on the central coast in Tuxpan and Santiago (Escalante & Navarro-Sigüenza, 1988). In central Nayarit, García (1995) reported a flock of 5 individuals in the micro-region of the municipality of Tepic. Howell (1999) reported the species on a road leading to El Mirador del Águila, near Tepic; however, neither study gave exact localities or particular data on the location of the species.

Although the species has been reported in Nayarit, there are no recent reports with specific information on the use of habitat by the species, and there is a great need for such studies in the state given that Marín-Togo et al. (2012) indicate areas of extirpation of the species in Nayarit. The objective of this study was to report a population of Military Macaws in the central part of the state of Nayarit. We describe the activities of the Military Macaw at the study sites, as well as their use of cavities in trees and hillside cliff, and we estimate the number of encounters of individuals of the species over a 5 year period (2008–2014). Furthermore, we provide observations of the natural history for the species.

The studied sites of the Mirador del Aguila and Pilas are located to the southwest of the community of Salazares Nayarit, Mexico. The southwestern slope of the cliff named Mirador del Aguila is located at 21°39′1.33″N, 104°58′26.90″W at an altitude of 400m. The Pilas is a small valley located at 21°40′23.82″N, 104°58′26.90″W at an altitude 180m. The distance between the sites is 3.7km. Both sites have a vegetation type of tropical semi-deciduous forest, with trees measuring 8–28m in height with diameters at breast height (DBH) greater than 40cm. Annual rainfall is 300–650mm and temperature range is between 24 and 43°C. The climate is subtropical humid (Caw) (Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013).

The first record of the species in the community of Salazares was obtained in 2007, when we observed a flying flock of 35 individuals about 4km from El Mirador del Águila. After that, we conducted 5 censuses between the 2 study sites – Las Pilas and Mirador del Aguila), 3 in the rainy season (June and July), and 2 during the dry season (November and December), between December 2008 and June 2014.

The study was performed with a linear transect (Brower, Zar, & von Ende, 1990) from the Pilas site to of the Mirador del Aguila site, where local residents and a co-author of the note (Villar-Rodríguez, C. L.) observed the species. Transects measured about 3.5km, which included an area of 30m approximately on both sides (Carreón, 1997). The route was followed during the morning and afternoon with binoculars, as they sought cavities in trees and on the side of the cliff. Also the number of encounters of individuals located in the transect were counted. This transect was also used to take behavioral data.

We conducted the first census of the transect in December 2008, registering 26 encounters with the Military Macaw between 8:00 and 11:00h, of which 15 macaws were observed perched and feeding in a capomo tree (Brosimun alicastrum) and a habilla tree (Hura polyandra) approximately for 30min. Also we observed holes in the cliff on the southwestern slope of Mirador del Aguila that were possibly used by the Military Macaw, due to the large number of feathers found on the ground nearby. However, we did not record the species using the cliff, possibly due to its daytime activities, since the observation was made around 13:00h. It has been reported at other sites in Mexico that individuals leave their roosting sites early in the morning to visit feeding sites (5:00–6:00h) and return during the afternoon (17:00–19:00h), which indicates that they are possibly using the cliff as a roosting site in this season (Carreón, 1997; Gaucín, 2000; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008).

In November 2009, we performed the route in transect and registered 25 encounters with individuals of the Military Macaw. At 20:35h, 19 individuals were observed flying northwest, possibly originating from the cliff of Mirador del Aguila. Six individuals were observed at 17:45h in 3 cavities of the southwest slopes of the cliff of Mirador del Aguila. Three pairs of macaws were spotted entering and leaving the cavities; they perched in trees near the cavities and performed vocalizations; at 18:45h they made flights and entered their respective cavities. These cavities could possibly be used as roosts during this season, as recorded in 2008 (Forshaw, 2010; Gaucín, 2000).

In July 2010, we found 4 newly occupied cavities in this cliff; in one of the cavities was registered activity, at 12:35h, an individual left the cavity in a northeastern direction, and returned at 13:23h. The individual perched and performed vocalizations, another individual came out of the cavity and walked to the perch, where he spent 25min outside the cavity, time that was employed by the other individual in feeding and then returning to the cavity. This was observed again at 17:13h. This activity has been observed at other sites as part of incubation behavior (Gaucín, 2000; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008), although it is necessary to make more precise studies of breeding at the site. Three pairs of macaws were recorded entering the other 3 occupied cavities at 19:20h.

From July 2010 to June 2014, a search of trees with potential cavities used by the Military Macaw was performed. The search was conducted on the transect of the Pilas and the southwestern slopes of the cliff of Mirador del Aguila, since the vegetation in the locality is suitable for nesting of this species (Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2013). Additionally, simultaneous counts of A. militaris individuals were conducted by 3 independent observers with binoculars in the same transect. The count points were separated approximately every 900m.

In July 2010 on a transect at 7:00h, we detected 1 cavity in B. alicastrum at a height of 8m (the height was measured with a rangefinder, Nikon Laser 600). In the cavity a macaw was observed leaving the cavity and walking away from the tree. We waited for about 30min to confirm the arrival of the individual, which returned and perched outside of the cavity, where it waited for another individual. These individuals were grooming and regurgitating. Macaws can spend much time investigating cavities, possibly to nest or roost (Almazán-Núñez & Nova-Muñoz, 2009; Juárez, Grilli, Pagano, Rumi, & Croome, 2012). Also grooming behavior and regurgitation strengthen the bonds between the couples (Carreón, 1997). This behavior is also seen during the non-breeding period, and could identify this cavity as a roost (Brightsmith, 2005; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008).

In June 2011, we conducted a walk within the Pilas site from around 10:00 to 12:00h, and recorded 3 cavities, 2 located in Ficus crocata and 1 in B. alicastrum at a height of 6, 8, and 10m, respectively. The arrival of a pair of macaws was observed at 10:45h in the cavity of 8m found in F. crocata. One individual entered the cavity at 11:25pm, while the other vocalized. At 13:05h the couple flew away heading southwest. Greater activity was observed in the second cavity (6m) of F. crocata throughout the day. The arrival of 1 individual at the cavity was recorded at 11:45, 14:32, and 17:09h, while the other came out of the cavity. The couple vocalized and performed regurgitation. The visits lasted from 23min to 35min. Carreón (1997), Gaucín (2000), and Rivera-Ortíz et al. (2008) indicate that male macaws feed the females 3–4 times during the day. The female is located within the cavity incubating, so that is increased activity during the daytime. Therefore, due to the activity recorded, this cavity could have been a nest.

According to the activities recorded in the study area, we can state 2 things, the macaws of this region probably are reproducing both in tree cavities and cliff cavities, although more data are needed to corroborate this, and possibly the breeding season could be from May to July. It has been documented for populations in south-central Mexico and the northwest of the Pacific that the Military Macaw is reproducing between May and July (Gaucín, 2000; Jiménez-Arcos et al., 2012; Nocedal et al., 2006; Rivera-Ortíz et al., 2008; Rubio et al., 2007). The biogeographic region of the population of the Salazares community, Nayarit is located in the province of the northwestern Pacific coast (Morrone, 2005), so it more likely that this population follows the breeding period of the populations that are within the same biogeographic province (e.g. Nocedal et al., 2006; Rubio et al., 2007).

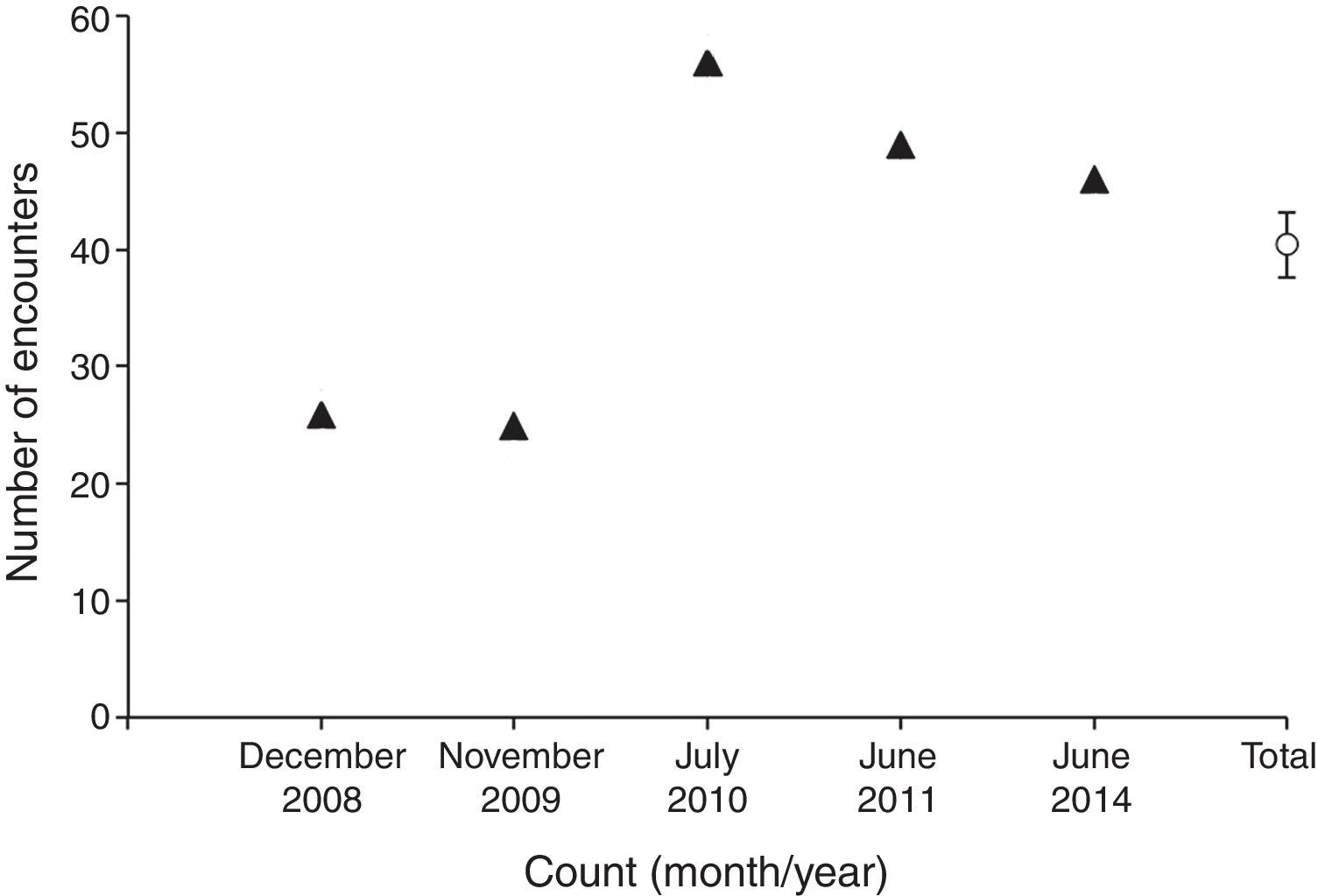

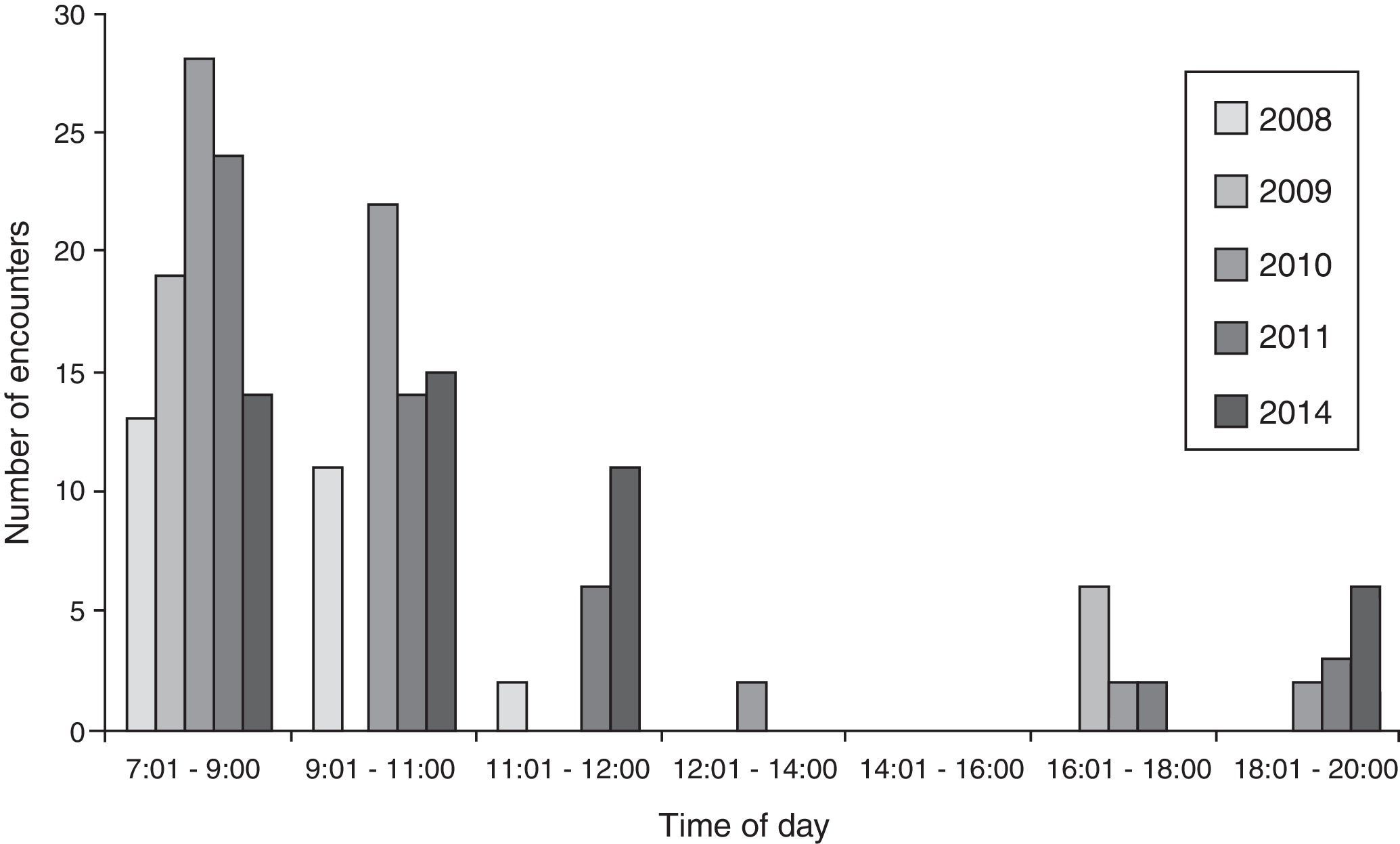

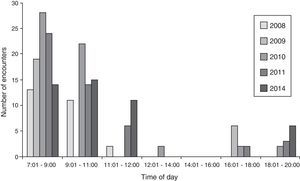

In 5 visits to the study areas, we recorded an average of 41.2±2.7 individuals registered by encounter throughout the day; we observed the largest number of encounter in July 2010 (55 registered encounters) and the lowest in November 2009 (25 registered encounters) (Fig. 1). In general, the greatest number of encounters observed during the 5 years were during the diurnal schedules (Fig. 2). The fluctuations of the encounters recorded of the Military Macaw from 2008 to 2014 were very different, possibly because macaws make seasonal movements in response to fluctuations in food availability from one period to another (Contreras-González et al., 2009; Rubio et al., 2007). Besides, intensive sampling would be required to have a real representation of abundance in the study area.

In 2014, the macaws were observed eating in B. alicastrum and H. polyandra trees, on the southwestern slopes of Mirador del Aguila at around 11:00h in pairs and groups of 2–4 individuals (25 individuals total). The part consumed of B. alicastrum was pulp. The seeds were dropped on the ground. From H. polyandra they consumed seeds, taking 45min to feed on these trees. Between 12:00h and 15:00h, macaws reduced their activity to such an extent that they were difficult to observe. Their activity increased again from 17:00h until 19:00h before nightfall.

This record of the presence of the Military Macaw is relevant for 2 reasons, it provides information on the presence of a breeding population in central Nayarit, and it is the first record in Mexico of a possible observation of 2 nesting conditions in the same location of the species, being the Salazares site, an area of importance for the protection of the Military Macaw that must be included in conservation plans in Mexico (Arizmendi & Márquez, 2000). Further comparative studies are needed to understand the reproductive behavior of this species and the local adaptation to each particular nesting condition. This could lay the groundwork for extending potential ecological studies in the future, because there are mechanisms associated with predation pressure and competition for use of cavities related to the final selection of nesting sites by parrots (Brightsmith, 2005).

The authors thank the municipal authorities and people of the community of Salazares for providing facilities, as well as Oscar Sanabria, Veronica García, Gabriela Barrera, Víctor Jiménez-Arcos, and Juan Peñaloza-Ramírez, and all who helped in the fieldwork. Logistical support for this work was provided by projects to Ken Oyama, María del Coro Arizmendi (Conacyt projects DT006), and Sofía Solórzano (Conacyt projects 60270). A. M. Contreras-González thanks the Conacyt (164991) for the PhD scholarship to conduct studies at the Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, UNAM. F. A. Rivera-Ortíz thanks the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, for the postdoctoral fellowship at the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, UNAM.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.