To evaluate alcohol/tobacco and/or illicit drug misuse in Chronic Diseases (CDs).

MethodsA cross-sectional study with 220 CDs adolescents and 110 healthy controls including: demographic/anthropometric data; puberty markers; modified questionnaire evaluating sexual function, alcohol/smoking/illicit drug misuse and bullying; and the physician-conducted CRAFFT (car/relax/alone/forget/friends/trouble) screen tool for substance abuse/dependence high risk.

ResultsThe frequencies of alcohol/tobacco and/or illicit drug use were similar in both groups (30% vs. 34%, p=0.529), likewise the frequencies of bullying (42% vs. 41%, p=0.905). Further analysis solely in CDs patients that used alcohol/tobacco/illicit drug versus those that did not use showed that the median current age [15 (11–18) vs. 14 (10–18) years, p<0.0001] and education years [9 (5–14) vs. 8 (3–12) years, p<0.0001] were significant higher in substance use group. The frequencies of Tanner 5 (p<0.0001), menarche (p<0.0001) and spermarche (p=0.001) were also significantly higher in patients with CDs that used alcohol/tobacco/illicit, likewise sexual activity (23% vs. 3%, p<0.0001). A trend of a low frequency of drug therapy was observed in patients that used substances (70% vs. 82%, p=0.051). A positive correlation was observed between CRAFFT score and current age in CD patients (p=0.005, r=+0.189) and controls (p=0.018, r=+0.226).

ConclusionsA later age was evidenced in CDs patients that reported licit/ilicit drug misuse. In CDs adolescent, substance use was more likely to have sexual intercourse. Our study reinforces that these patients should be systematically screened by pediatricians for drug related health behavioral patterns.

Avaliar o uso indevido de álcool/tabaco e/ou de drogas ilícitas em Doenças Crônicas (DCs).

MétodosEstudo transversal com 220 adolescentes com DCs e 110 controles saudáveis, incluindo: dados demográficos/antropométricos; marcadores de puberdade; questionário modificado de avaliação da função sexual, abuso de álcool/tabagismo/drogas ilícitas e assédio moral; e o uso do instrumento CRAFFT (car/relax/alone/forget/friends/trouble) pelo medico para o abuso/dependência de substâncias de alto risco.

ResultadosAs frequências de uso de álcool/tabaco e/ou drogas ilícitas foram semelhantes em ambos os grupos (30% vs. 34%, p=0,529), assim como as frequências de assédio moral (42% vs. 41%, p=0,905). Uma análise mais aprofundada apenas em pacientes com DCs que usaram álcool/tabaco/droga ilícita versus aqueles que não usaram mostrou que a idade mediana atual [15 (11-18) vs. 14 (10-18) anos, p<0,0001] e anos de escolaridade [9 (5-14) vs. 8 (3-12) anos, p<0,0001] foram significativamente maiores no grupo que fazia uso das substâncias. As frequências de Tanner 5 (p<0,0001), menarca (p<0,0001) e espermarca (p=0,001) também foram significativamente maiores em pacientes com DCs que usaram álcool/tabaco/drogas ilícitas, assim como a atividade sexual (23% vs. 3%, p<0,0001). A tendência de baixa frequência de terapia com medicamentos foi observada em pacientes que usaram substâncias (70% vs. 82%, p=0,051). Observou-se uma correlação positiva entre o score no CRAFFT e idade atual em pacientes com DCs (p=0,005, r=+0,189) e controles (p=0,018, r=+0,226).

ConclusõesA idade mais avançada foi demonstrada em pacientes com DCs que relataram uso indevido de drogas lícitas/ilícitas. Em adolescente com DCs, o uso das substâncias resultou em maior propensão à prática de relações sexuais. Nosso estudo reforça que esses pacientes devem ser sistematicamente avaliados pelos pediatras em relação a padrões de comportamento de saúde relacionados com drogas.

Adolescence is a developmental stage characterized by biological and social changes.1,2 Risk patterns may begin in this period of life, including substance misuse (alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs)1 and high-risk sexual behaviors.3 Harmful phenomena of peer victimization, such as bullying, is also a relevant problem in healthy adolescents4 and in those with chronic diseases (CDs).5

Of note, the prevalence of chronic conditions has increased in pediatric population,6 and 10% of adolescents suffer from CDs.7 However, to our knowledge, misuse of substances evaluated by a screening tool,8 as well as assessment of bullying and sexual function, have not been simultaneously studied in an adolescent CDs population.

Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to evaluate alcohol, tobacco and/or illicit drug misuse in adolescent CDs patients and healthy controls. The possible associations between the substance misuse in CDs patients according to sexual function, bullying, demographic data, puberty markers, CDs groups and drug therapy use were also assessed.

MethodFrom February to December 2014, a cross-sectional study was carried out involving 220 consecutive outpatient adolescents (current age 10–19 years according to World Health Organization criteria) with pediatric CDs. All of them were followed at the Adolescent Unit of our University Hospital and none of them had unwillingness to participate. The control group included 110 healthy adolescents (rate 2:1), without CDs, consecutively admitted to the outpatient clinic and referred from primary and secondary health care services to the Adolescent Unit of our University Hospital. This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Hospital. All adolescents and their parents signed a consent/assent term.

This study included a modified questionnaire evaluating sexual function,9 alcohol/tobacco/illicit drug use and bullying was applied. The Portuguese CRAFFT (mnemonic acronym of car, relax, alone, forget, friends and trouble) screen (CRAFFT/CEASER) version was performed in both groups.3,8 Demographic/anthropometric data and puberty markers assessments were also evaluated.

A pilot study was carried out in 30 consecutive healthy and adolescents with CDs, who were tested and retested 1–2 months. The pre-test evaluated the subject comprehension of the questions, the consistency and coherence of the answers and the time taken to answer the questionnaire. The modified questionnaire included 14 questions with the option of answer “yes/no” or age/number of times about sexual function,9 bullying and alcohol/tobacco/illicit drugs use. Sexual function assessment included9: age at first sexual intercourse, sexual intercourse in the last month, use of male contraceptive (condom) in the first sexual activity, current use of oral and emergency contraceptive, knowledge of sexual activity by parents and total number of sexual partners. Alcohol/tobacco and drugs [illicit inhalants drug (glue sniffing, aerosol and solvents) and illicit drugs [marijuana, stimulants (cocaine, crack and speed), poppers, LSD, opiates, heroin, crystal meth and ecstasy] use were also assessed: age at alcohol initiation, number of days of alcohol use in the last 30 days, age at smoking initiation, number of days smoking cigarettes in the last 30 days, age at illicit drug initiation and number of days using illicit drugs in the last 30 days. Bullying, which is defined as a recurrent exposure to emotional and/or physical aggression, was obtained by a “yes/no” answer to the question (“Have you ever suffered bullying?”). The questionnaire was strictly confidential and was performed in the absence of legal guardians, relatives and friends.

The Portuguese version of physician-conducted CRAFFT (CRAFFT/CEASER) screen was used and consisted of 9 questions developed to screen adolescents for high-risk alcohol and drug misuse.8 This questionnaire is divided in two parts. Part A includes three questions regarding the use of alcohol, marijuana/hashish or another substance in the last twelve months. If the adolescent responded “no” to all three questions, only the question related to “car” of the B–part should be asked. If the adolescent answered “yes” to one of the opening questions, all of the questions of part B should be asked. B-part contained six questions, which are signs of problematic substance use. One point was given to each “yes” answer in the B-part of the questionnaire. The score ranged from 0 to 6. A total score of ≥2 indicated high risk for substance abuse/dependence and a need for additional assessment.3,8

Regarding socio-demographic and anthropometric data, current age, gender, years of education, weight and height were evaluated. Body mass index (BMI) was defined by the formula: weight in kilograms/height in square meters. The Brazilian socio-economic status were classified according to the ABEP (Associaça¿o Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa).10

Secondary sexual characteristics were classified according to Tanner pubertal changes.11 Age at first menstruation (menarche) and age at first ejaculation (spermarche) were registered based on memory recollection.

Chronic diseases, with disease duration more than three months, were classified in: Allergic/Immunologic, Cardiopulmonary, Dermatologic, Endocrinologic, Gastroenterologic, Hematologic, Neuropsychiatric, Renal and Rheumatic conditions. The use of drug therapy was also assessed.

The test–retest reliability of the modified questionnaire was verified for CDs population and healthy controls using the Kappa index. Results were presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (range) for continuous and number (%) for categorical variables. Data were compared by t or Mann–Whitney tests in continuous variables to evaluate differences between adolescents with CDs and controls, and between subgroups. For categorical variables, differences were assessed by Fisher's exact or Pearson chi-square tests. Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for correlations between CRAFFT score and age. The level of significance was set at 5% (p<0.05).

ResultsThe kappa index for test–retest was 0.850, demonstrating excellent reliability for the adolescents’ responses.

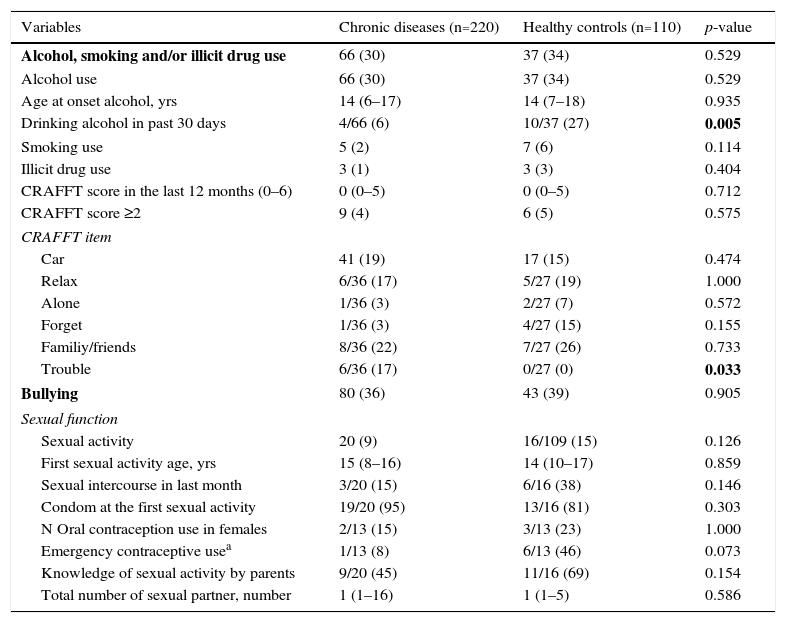

The frequencies of alcohol, tobacco and/or illicit drug use were similar in both adolescents with CDs and healthy controls (30% vs. 34%, p=0.529). The frequency of alcohol consumption in the past 30 days was significantly lower in adolescents with CDs compared with controls (6% vs. 27%, p=0.005). Illicit drugs were used by three CDs patients (marijuana, cocaine and/or poppers) and three controls (marijuana) (p=0.404). No difference was observed in the frequency of smoking (p=0.114). CRAFFT score ≥2 was similar in both groups (4% vs. 5%, p=0.575). The frequency of bullying was alike in both groups (36% vs. 39%, p=0.905) (Table 1). The median of age onset smoking was 14 years (11–15) in adolescents with CDs and was 14 years (7–15) in healthy controls. The median of age onset ilicit drug use was 14.5 years (14–15) in adolescents with CDs and was 14 years in healthy controls.

Alcohol, smoking and illicit drug use, and bullying in adolescents with chronic diseases and healthy controls.

| Variables | Chronic diseases (n=220) | Healthy controls (n=110) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol, smoking and/or illicit drug use | 66 (30) | 37 (34) | 0.529 |

| Alcohol use | 66 (30) | 37 (34) | 0.529 |

| Age at onset alcohol, yrs | 14 (6–17) | 14 (7–18) | 0.935 |

| Drinking alcohol in past 30 days | 4/66 (6) | 10/37 (27) | 0.005 |

| Smoking use | 5 (2) | 7 (6) | 0.114 |

| Illicit drug use | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.404 |

| CRAFFT score in the last 12 months (0–6) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–5) | 0.712 |

| CRAFFT score ≥2 | 9 (4) | 6 (5) | 0.575 |

| CRAFFT item | |||

| Car | 41 (19) | 17 (15) | 0.474 |

| Relax | 6/36 (17) | 5/27 (19) | 1.000 |

| Alone | 1/36 (3) | 2/27 (7) | 0.572 |

| Forget | 1/36 (3) | 4/27 (15) | 0.155 |

| Familiy/friends | 8/36 (22) | 7/27 (26) | 0.733 |

| Trouble | 6/36 (17) | 0/27 (0) | 0.033 |

| Bullying | 80 (36) | 43 (39) | 0.905 |

| Sexual function | |||

| Sexual activity | 20 (9) | 16/109 (15) | 0.126 |

| First sexual activity age, yrs | 15 (8–16) | 14 (10–17) | 0.859 |

| Sexual intercourse in last month | 3/20 (15) | 6/16 (38) | 0.146 |

| Condom at the first sexual activity | 19/20 (95) | 13/16 (81) | 0.303 |

| N Oral contraception use in females | 2/13 (15) | 3/13 (23) | 1.000 |

| Emergency contraceptive usea | 1/13 (8) | 6/13 (46) | 0.073 |

| Knowledge of sexual activity by parents | 9/20 (45) | 11/16 (69) | 0.154 |

| Total number of sexual partner, number | 1 (1–16) | 1 (1–5) | 0.586 |

The results are presented in n (%) and median (range), CRAFFT (car, relax, alone, forget, friends, trouble) screening test; BMI, body mass index.

A positive correlation was evidenced between CRAFFT score and current age in CDs patients (p=0.005, r=+0.189) and healthy controls (p=0.018, r=+0.226), likewise between CRAFFT score and education years in CDs (p=0.015, r=+0.164) and controls (p=0.039, r=+0.197). A positive correlation was observed between CRAFFT score and age of alcohol onset in CDs patients (p=0.021, r=+0.286) (Table 1).

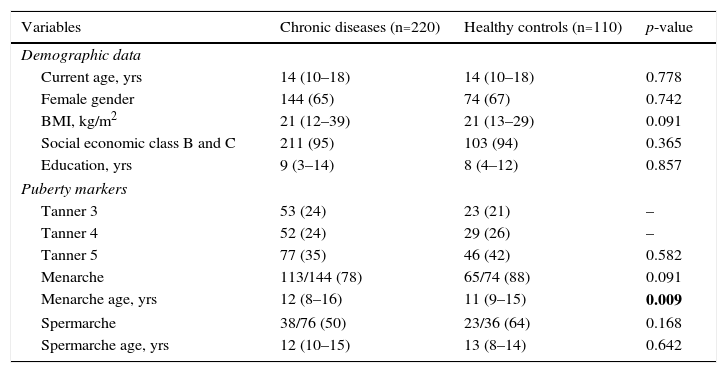

The median current age was similar between adolescent with CDs and healthy controls [14 (10–18) vs. 14 (10–18) years, p=0.778], likewise the frequency of female gender (65% vs. 67%, p=0.742), years of education [9 (3–14) vs. 8 (4–12) years, p=0.857], Brazilian socio-economic classes B or C (95% vs. 94%, p=0.365) and between Tanner 3, 4 and 5 (p=0.582). The median menarche age was significantly higher in the former group [12 (8–16) vs. 11 (9–15) years, p=0.009]. No difference was evidenced in the age at spermarche in both groups (p=0.642) (Table 2).

Demographic data and puberty markers in adolescents with chronic diseases and healthy controls.

| Variables | Chronic diseases (n=220) | Healthy controls (n=110) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Current age, yrs | 14 (10–18) | 14 (10–18) | 0.778 |

| Female gender | 144 (65) | 74 (67) | 0.742 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21 (12–39) | 21 (13–29) | 0.091 |

| Social economic class B and C | 211 (95) | 103 (94) | 0.365 |

| Education, yrs | 9 (3–14) | 8 (4–12) | 0.857 |

| Puberty markers | |||

| Tanner 3 | 53 (24) | 23 (21) | – |

| Tanner 4 | 52 (24) | 29 (26) | – |

| Tanner 5 | 77 (35) | 46 (42) | 0.582 |

| Menarche | 113/144 (78) | 65/74 (88) | 0.091 |

| Menarche age, yrs | 12 (8–16) | 11 (9–15) | 0.009 |

| Spermarche | 38/76 (50) | 23/36 (64) | 0.168 |

| Spermarche age, yrs | 12 (10–15) | 13 (8–14) | 0.642 |

The results are presented in n (%) and median (range); BMI, body mass index.

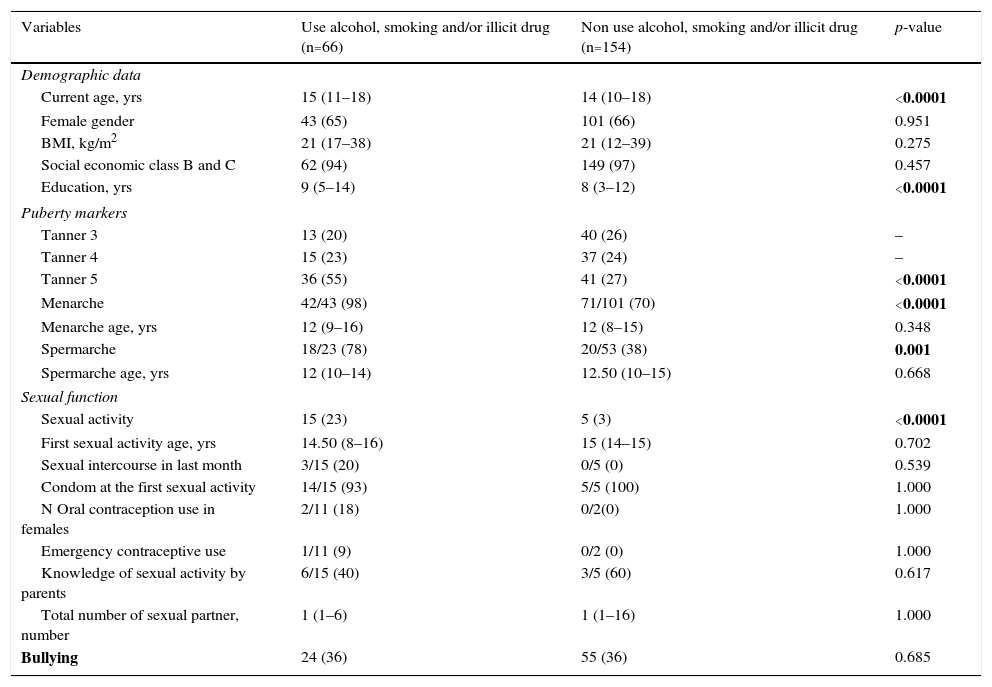

Further analysis solely of patients with CDs regarding alcohol/tobacco/illicit drug misuse showed that the median current age [15 (11–18) vs. 14 (10–18) years, p<0.0001] and education years [9 (5–14) vs. 8 (3–12) years, p<0.0001] were significant higher in those that used the aforementioned substances. The frequencies of Tanner 5 (p<0.0001), menarche (p<0.0001) and spermarche (p=0.001) were also significantly higher in the former group, likewise sexual activity (23% vs. 3%, p<0.0001) (Table 3).

Demographic data, puberty markers and bullying in adolescents with chronic diseases according to alcohol, smoking and illicit drug use.

| Variables | Use alcohol, smoking and/or illicit drug (n=66) | Non use alcohol, smoking and/or illicit drug (n=154) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Current age, yrs | 15 (11–18) | 14 (10–18) | <0.0001 |

| Female gender | 43 (65) | 101 (66) | 0.951 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21 (17–38) | 21 (12–39) | 0.275 |

| Social economic class B and C | 62 (94) | 149 (97) | 0.457 |

| Education, yrs | 9 (5–14) | 8 (3–12) | <0.0001 |

| Puberty markers | |||

| Tanner 3 | 13 (20) | 40 (26) | – |

| Tanner 4 | 15 (23) | 37 (24) | – |

| Tanner 5 | 36 (55) | 41 (27) | <0.0001 |

| Menarche | 42/43 (98) | 71/101 (70) | <0.0001 |

| Menarche age, yrs | 12 (9–16) | 12 (8–15) | 0.348 |

| Spermarche | 18/23 (78) | 20/53 (38) | 0.001 |

| Spermarche age, yrs | 12 (10–14) | 12.50 (10–15) | 0.668 |

| Sexual function | |||

| Sexual activity | 15 (23) | 5 (3) | <0.0001 |

| First sexual activity age, yrs | 14.50 (8–16) | 15 (14–15) | 0.702 |

| Sexual intercourse in last month | 3/15 (20) | 0/5 (0) | 0.539 |

| Condom at the first sexual activity | 14/15 (93) | 5/5 (100) | 1.000 |

| N Oral contraception use in females | 2/11 (18) | 0/2(0) | 1.000 |

| Emergency contraceptive use | 1/11 (9) | 0/2 (0) | 1.000 |

| Knowledge of sexual activity by parents | 6/15 (40) | 3/5 (60) | 0.617 |

| Total number of sexual partner, number | 1 (1–6) | 1 (1–16) | 1.000 |

| Bullying | 24 (36) | 55 (36) | 0.685 |

The results are presented in n (%) and median (range); CRAFFT (car, relax, alone, forget, friends, trouble) screening test; BMI, body mass index.

Of our 9 patients with CDs with CRAFFT score ≥2, rheumatic diseases were found in 8 (juvenile idiopathic arthritis in three patients, juvenile dermatomyositis in one, childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in one, Sjögren syndrome in one, Takayasu arteritis in one and Henoch–Schönlein purpura in one) and Allergic disease in one patient (asthma).

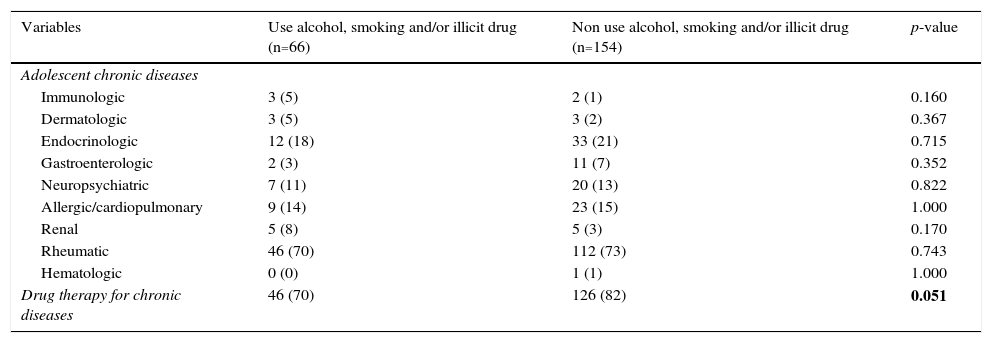

The frequencies of chronic conditions in patients that used alcohol/tobacco/illicit drug versus those that did not use were similar (p>0.05). A trend of a low frequency of drug therapy was evidenced in patients that used substances compared to those that did not used (70% vs. 82%, p=0.051) (Table 4).

Adolescent chronic diseases and drug therapy according to alcohol, smoking and illicit drug use the results are presented in n (%).

| Variables | Use alcohol, smoking and/or illicit drug (n=66) | Non use alcohol, smoking and/or illicit drug (n=154) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent chronic diseases | |||

| Immunologic | 3 (5) | 2 (1) | 0.160 |

| Dermatologic | 3 (5) | 3 (2) | 0.367 |

| Endocrinologic | 12 (18) | 33 (21) | 0.715 |

| Gastroenterologic | 2 (3) | 11 (7) | 0.352 |

| Neuropsychiatric | 7 (11) | 20 (13) | 0.822 |

| Allergic/cardiopulmonary | 9 (14) | 23 (15) | 1.000 |

| Renal | 5 (8) | 5 (3) | 0.170 |

| Rheumatic | 46 (70) | 112 (73) | 0.743 |

| Hematologic | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.000 |

| Drug therapy for chronic diseases | 46 (70) | 126 (82) | 0.051 |

Our study evaluated simultaneously adolescent's health problems in CDs patients and healthy controls. In adolescents with CDs, substance use was observed in later age and was more likely to sexual intercourse compared to those that did not use licit/illicit drug.

The advantage of this study was the assessment of physician-conducted CRAFFT (CEASER) screening tool for substance misuse in adolescents.3,8 The use of the questionnaire with excellent test–retest reliability regarding sexual function, bullying and substances use was also relevant. Additionally, a healthy control group with comparable age, gender, education and socio-economic class was also observed in our study, since these data were previously related with bullying and substance misuse.1,3,12,13

Alcohol intake was reported by approximately one third of our CDs patients, even though a low intake frequency in the last month. The prevalence of alcohol use in adolescents varies from 7.8% to 78.9%12,14,15 around the world and from 26% to 71% in Brazil.16–21 There are studies in adolescents with specific CDs, generally with small samples and variable frequencies of alcohol use (4.8%–70%), such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis,22 obesity and overweight,23 asthma,24 cystic fibrosis and sickle cell disease.25 This finding in our CDs patients may be related to the availability of alcohol at parties, pubs, stores and homes in Brazil.16

Importantly in the evaluation of only adolescents with CDs, we observed that use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs occurred in CDs patients that presented higher age, higher education background and post pubertal markers. The avoidance of substance use in early adolescence may be related to overprotection of parents and primary caregivers. In contrast, a more liberal parental attitude may contribute to an increase in substance misuse later on in life. Moreover, severe CDs that required higher frequencies of medication may have contributed to the low use of illicit and licit drugs.

The adolescents may develop a drinking pattern that is socially acceptable and a small group of CDs patients’ misused alcohol more frequently. We applied a screening procedure for substance misuse and 4% of our CDs patients had a higher risk for substance abuse/dependence. A positive correlation was also evidenced between CRAFFT score and current age, indicating a higher risk for harmful substance misuse in older CDs adolescents.

Smoking was reported only by 2% of our CDs patients. This aspect has also been observed in adolescents of our continental country due to ban on smoking advertising,26 use of warnings on cigarettes packages27 and prohibition in public places.28 The use of any illicit drug (marijuana, solvents, cocaine or crack) was reported in 2.8% of adolescents in a Brazilian survey,21 and this result was higher than in our CDs patients.

Interestingly, CDs substance users engaged more in sexual activity, and may present a higher risk for sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancy and low contraceptive use.29,30 This finding may also be related to the fact that the patients were older and probably had higher sexual maturity. However, this study did not evaluate if drinking influenced high-risk sexual behavior in CDs patients.

In addition, bullying was frequently reported in CDs and seems not to be linked to substance use. Adolescents with CDs may suffer from this victimization,4,5 may induce anxiety-depressive disorder and interfere with proper adherence to medication use. A prospective study evaluating prevalence and intensity of bullying in a large sample of CDs patients will be required.

The main limitation of the present study was the use of a convenience sample for CDs patients in a tertiary University Hospital, predominantly of rheumatic, endocrinologic, allergic and cardiopulmonary diseases. A small sample may also have reduced our power to detect differences between the two groups and the cross sectional design nature of our study did not allow the evaluation of temporality between exposure and outcome. We did not evaluate disease activity criteria for all CDs, and indeed this finding may modify the behavior. Moreover, the healthy controls and CDs patients were referred to the adolescent clinic of our University Hospital to guidance about sexual function and birth control, emotional problems and drugs issues.

A need for additional assessment and therapeutic intervention with a multidisciplinary and multiprofessional team is required for CDs adolescents and families at risk for substance misuse. Confidential discussion of illicit and licit drugs and other potentially risky behaviors should be included in the routine care of clinics that followed-up CDs patients.

In conclusion, a later age was evidenced in CDs patients that reported licit/ilicit drug use. CDs substance users were more likely to have sexual intercourse. Our study reinforces that these patients should be systematically screened by pediatricians for sexual, alcohol and drug related health behavioral patterns.

FundingThis study was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2009/51897-5, 2011/12471-2 and 2014/14806-0 to CAS), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ 302724/2011-7 to CAS), Federico Foundation (to CAS), and Núcleo de Apoio à Pesquisa “Saúde da Criança e do Adolescente” da USP (NAP-CriAd) to CAS.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank Dr. JR Knight and Dr. P Schram for supplying the Portuguese version of CRAFFT screen (CEASER) instrument, Boston Children's Hospital, Mass, USA. Our gratitude to Ulysses Doria–Filho for the statistical analysis.