To analyze studies that assessed the anthropometric parameters waist circumference (WC), waist-to-height ratio (WHR) and neck circumference (NC) as indicators of central obesity in children.

Data sourcesWe searched PubMed and SciELO databases using the combined descriptors: “Waist circumference”, “Waist-to-height ratio”, “Neck circumference”, “Children” and “Abdominal fat” in Portuguese, English and Spanish. Inclusion criteria were original articles with information about the WC, WHR and NC in the assessment of central obesity in children. We excluded review articles, short communications, letters and editorials.

Data synthesis1,525 abstracts were obtained in the search, and 68 articles were selected for analysis. Of these, 49 articles were included in the review. The WC was the parameter more used in studies, followed by the WHR. Regarding NC, there are few studies in children. The predictive ability of WC and WHR to indicate central adiposity in children was controversial. The cutoff points suggested for the parameters varied among studies, and some differences may be related to ethnicity and lack of standardization of anatomical site used for measurement.

ConclusionsMore studies are needed to evaluate these parameters for determination of central obesity children. Scientific literature about NC is especially scarce, mainly in the pediatric population. There is a need to standardize site measures and establish comparable cutoff points between different populations.

Analisar estudos que avaliaram os parâmetros antropométricos perímetro da cintura (PC), relação cintura/estatura (RCE) e perímetro do pescoço (PP) como indicadores da obesidade central em crianças.

Fontes dos dadosRealizou-se busca nas bases de dados PubMed e SciELO utilizando os descritores combinados: “Perímetro da cintura”, “Relação cintura/estatura”, “Perímetro do pescoço”, “Crianças” e “Gordura Abdominal” e seus correlatos em inglês e espanhol. Os critérios de inclusão foram: artigos originais sobre o PC, a RCE e o PP na avaliação da obesidade central em crianças, publicados em português, inglês ou espanhol. Excluíram-se artigos de revisão, comunicação breve, cartas e editoriais.

Síntese dos dadosObtiveram-se 1.525 resumos, sendo selecionados 68 artigos para análise na íntegra. Destes, 49 fizeram parte da revisão. O PC foi o parâmetro mais utilizado nos estudos, seguido pela RCE. Já o PP ainda é pouco estudado em crianças. Houve controvérsias quanto à capacidade preditiva da adiposidade central em crianças do PC e da RCE. Os pontos de corte sugeridos para os parâmetros foram diversificados entre os estudos, e essas diferenças podem estar relacionadas à etnia e à falta de padronização do ponto anatômico utilizado na aferição da medida.

ConclusõesMais estudos são necessários para avaliar esses parâmetros na determinação da obesidade central na infância, especialmente em relação ao PP, para o qual a literatura ainda é escassa, principalmente na população infantil. Há necessidade de padronização do local das medidas para o estabelecimento de pontos de cortes comparáveis entre diversas populações.

The prevalence of obesity in children has increased worldwide1 and is associated with risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic disorders, which, due to their chronic and insidious nature, require careful monitoring in childhood, aimed at early detection and the establishment of interventions to prevent complications in adulthood.2,3

The body mass index (BMI) is the most commonly used parameter in all age groups to determine overweight and obesity. However, it does not provide accurate information on body fat distribution.2 Fat distribution is related to future health risks, and central obesity is more strongly associated to several risk factors for cardiovascular diseases than overall obesity.4

Body fat distribution can be verified through several anthropometric parameters. In recent years, new indicators have been proposed to evaluate central adiposity, such as waist circumference (WC), waist/height ratio (WHR), and neck circumference (NC). NC is a simple technique that can be used in screening children and adolescents, as well as in adults, with good performance as an indicator of central adiposity in both genders.5

WHR has also been proposed as a measure to evaluate central adiposity in childhood and adulthood in several populations.6 NC is a relatively new parameter for the evaluation of children and adolescents, of simple and fast measurement, and is an indicator of subcutaneous fat distribution in the upper body.7

However, despite these studies, there is no work in the literature aiming at a critical analysis of all three parameters as markers of adiposity in childhood.

In this context, this review aimed to analyze studies that evaluated WC, WHR, NC, and anthropometric parameters as indicators of central obesity in children.

Data sourceThe present study consisted of an integrative review performed after a search in the PubMed and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) databases. The bibliographic search was conducted in national and international journals in the databases through the portal of Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). The keywords used to search for articles were: “waist circumference”, “waist-to-height ratio”, “neck circumference”, “Children”, “abdominal fat”, and its correlates in Portuguese and Spanish. To search in PubMed, the following combination of descriptors in English was used: “Waist circumference”, “Waist-to-height ratio”, “Neck circumference”, “Abdominal fat”, and “Children”, using as search criteria “All fields” for the first four and “Title/Abstract” for the latter. The search at SciElo, in turn, used the combination of descriptors in Portuguese and Spanish (“Perímetro da cintura/Circunferencia de la cintura”, “Relação cintura/estatura/Relación cintura/talla”, “Perímetro do pescoço/Circunferencia del cuello”, “Gordura abdominal/Grasa abdominal” e “Crianças/Niños”), to include articles published in national and international journals, in both languages, using as search criteria “All fields” for these descriptors.

Identified studies were selected by reading the abstracts, using, as an inclusion criterion, original articles that had information about the WC, NC, and WHR in the assessment of central obesity in children, in Portuguese, English, or Spanish. The exclusion criteria were: review articles, short communications, letters, and editorials. There was no limitation regarding the time of publication, considering that studies on such parameters are relatively recent in this age group.

Based on selected articles, a file was created for information extraction, including: names of authors, year of publication, purpose, location and type of study, sample size and characteristics, method of anthropometric measurements, statistical analyses performed, main results, and suggested cutoffs.

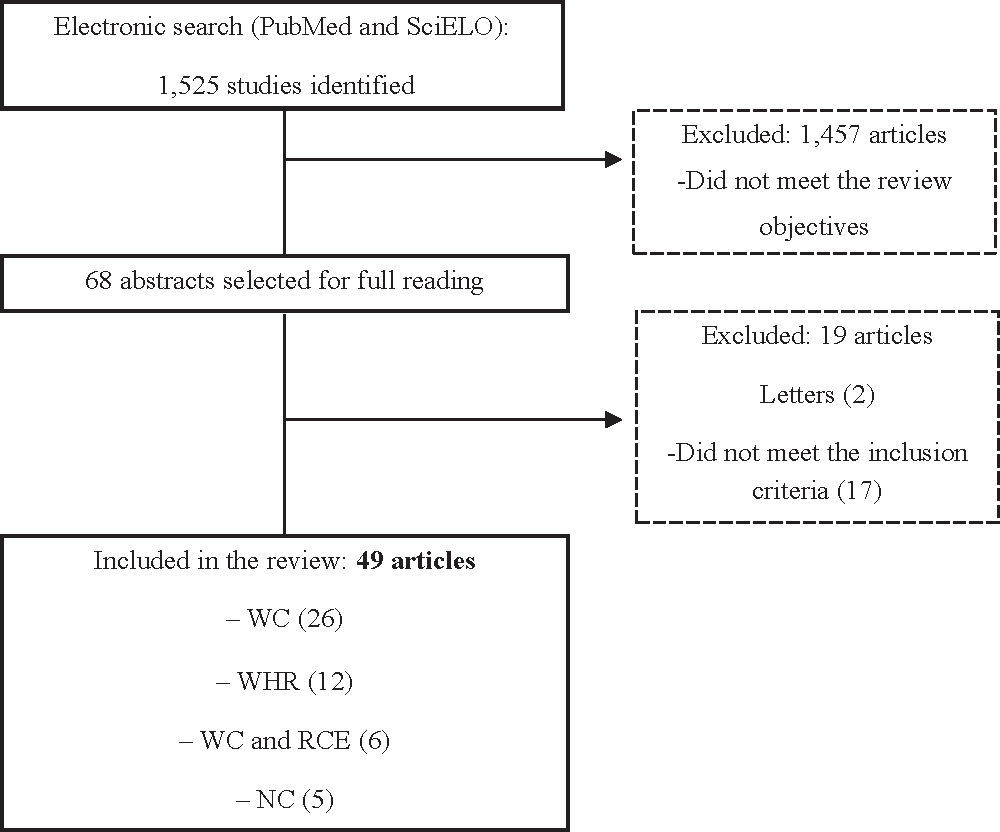

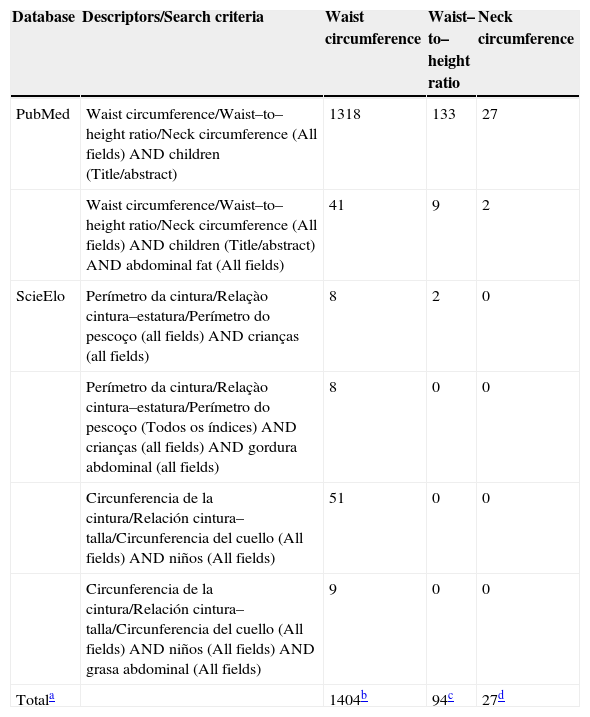

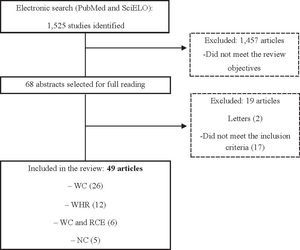

Data synthesisThe database search retrieved 1,525 studies on the topic. The number of identified articles categorized by database and descriptors used are described in Table 1. Initially, articles were analyzed based on the relevance of titles and abstracts, and 1,457 studies were excluded for not meeting the objectives of this review, which focused on the use of anthropometric parameters in the assessment of central obesity in children. Thus, 68 articles were selected for full reading.

Number of identified articles categorized by database and descriptors used in the search on the use of anthropometric parameters in the determination of central adiposity in children

| Database | Descriptors/Search criteria | Waist circumference | Waist–to–height ratio | Neck circumference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Waist circumference/Waist–to–height ratio/Neck circumference (All fields) AND children (Title/abstract) | 1318 | 133 | 27 |

| Waist circumference/Waist–to–height ratio/Neck circumference (All fields) AND children (Title/abstract) AND abdominal fat (All fields) | 41 | 9 | 2 | |

| ScieElo | Perímetro da cintura/Relaçào cintura–estatura/Perímetro do pescoço (all fields) AND crianças (all fields) | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| Perímetro da cintura/Relaçào cintura–estatura/Perímetro do pescoço (Todos os índices) AND crianças (all fields) AND gordura abdominal (all fields) | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Circunferencia de la cintura/Relación cintura–talla/Circunferencia del cuello (All fields) AND niños (All fields) | 51 | 0 | 0 | |

| Circunferencia de la cintura/Relación cintura–talla/Circunferencia del cuello (All fields) AND niños (All fields) AND grasa abdominal (All fields) | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Totala | 1404b | 94c | 27d |

However, after reading the articles in full, 19 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Thus, 49 articles were part of this review, which were published in the period between 2000 and 2013. Among the selected studies, most (26 articles) referred to WC,3,5,8–31 12 articles assessed WHR,32–43 six studies assessed both parameters,44–49 and only five assessed NC.2,50–53Fig. 1 presents the flowchart of the steps performed to select the studies for this review.

Waist Circumference (WC)WC is the most widely used measure to assess abdominal obesity, and several studies have addressed its capacity to indicate central fat accumulation in children, as well as its positive correlation with BMI,8–10,44 total fat,11 and upper body fat percentage.12 Some authors suggest that this parameter is more consistent in terms of the balance between sensitivity and specificity to evaluate obese and non-obese children than BMI and WHR,45 and is a good indicator of central adiposity in children.13 Furthermore, it demonstrates a satisfactory performance in predicting total body fat content,11,14 as well as an indicator of upper body fat mass.5,15

However, some studies have not shown favorable results when using this parameter. Reilly et al,16 studying English children aged 9-10 years, compared the capacity of BMI and WC, in percentiles, to diagnose increased fat mass. The authors observed higher specificity of BMI percentile for both genders, using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) as the reference method. In turn, in a study of Venezuelan children and adolescents aged 7-17 years using the subscapular/triceps skinfold ratio as the reference method in the analysis of ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curve, Perez et al46 observed that WC was not effective to identify fat distribution, not showing satisfactory sensitivity and specificity.

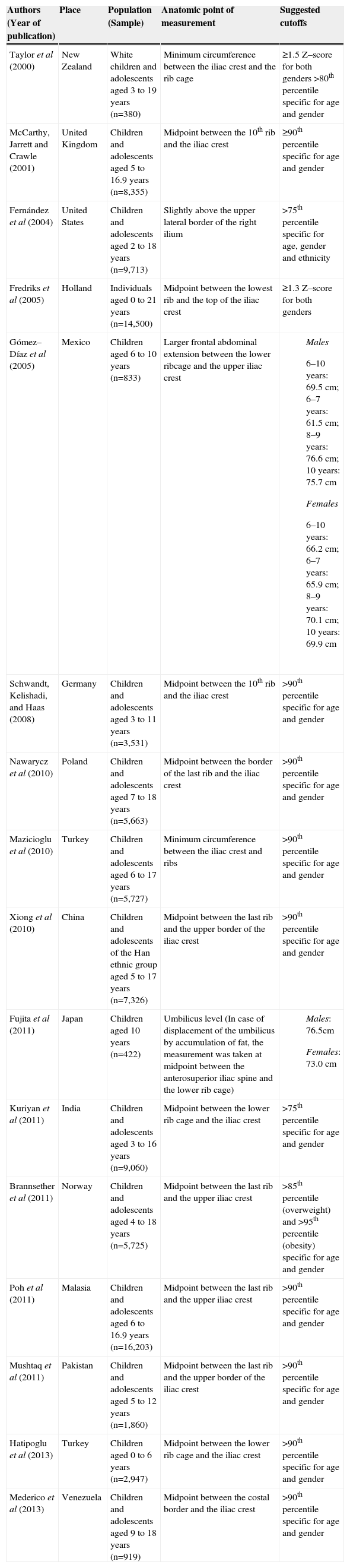

Regarding reference values, studies conducted in different parts of the world have established WC cutoffs to determine central adiposity. The values were established using the LMS (L=lambda, asymmetry; M=Mi, median; and S=sigma, coefficient of variation) method, and were shown as percentile values and standard deviations,3,17–24,30,31,47 or were based on the ROC analysis, considering the BMI score as overweight/obesity according to the classification of the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)25,26,48 or excess upper body fat measured by DXA5,49 as reference methods.

In most studies, the 90th percentile of the distribution of WC values was used as the critical value.17–20,22–24,26,47 Although some studies have shown significant differences when the WC measurement is performed at different anatomic sites in children,27,28 there was no agreement regarding the measurement site. Some studies performed the measure at midpoint between the last rib and the top of the iliac crest;3,17–24,47,48 others measured at “the minimum circumference between the iliac crest and the rib cage,5,26 slightly above the upper lateral border of the right ilium,29 or at the largest frontal extension of the abdomen between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest.25 One study performed the measurement in two places: at navel level and at midpoint between the anterosuperior iliac spine and the bottom of the rib cage.49Table 2 presents a summary of these studies.

Waist circumference cutoffs for central adiposity assessment in children

| Authors (Year of publication) | Place | Population (Sample) | Anatomic point of measurement | Suggested cutoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al (2000) | New Zealand | White children and adolescents aged 3 to 19 years (n=380) | Minimum circumference between the iliac crest and the rib cage | ≥1.5 Z–score for both genders >80th percentile specific for age and gender |

| McCarthy, Jarrett and Crawle (2001) | United Kingdom | Children and adolescents aged 5 to 16.9 years (n=8,355) | Midpoint between the 10th rib and the iliac crest | ≥90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Fernández et al (2004) | United States | Children and adolescents aged 2 to 18 years (n=9,713) | Slightly above the upper lateral border of the right ilium | >75th percentile specific for age, gender and ethnicity |

| Fredriks et al (2005) | Holland | Individuals aged 0 to 21 years (n=14,500) | Midpoint between the lowest rib and the top of the iliac crest | ≥1.3 Z–score for both genders |

| Gómez–Díaz et al (2005) | Mexico | Children aged 6 to 10 years (n=833) | Larger frontal abdominal extension between the lower ribcage and the upper iliac crest |

|

| Schwandt, Kelishadi, and Haas (2008) | Germany | Children and adolescents aged 3 to 11 years (n=3,531) | Midpoint between the 10th rib and the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Nawarycz et al (2010) | Poland | Children and adolescents aged 7 to 18 years (n=5,663) | Midpoint between the border of the last rib and the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Mazicioglu et al (2010) | Turkey | Children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years (n=5,727) | Minimum circumference between the iliac crest and ribs | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Xiong et al (2010) | China | Children and adolescents of the Han ethnic group aged 5 to 17 years (n=7,326) | Midpoint between the last rib and the upper border of the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Fujita et al (2011) | Japan | Children aged 10 years (n=422) | Umbilicus level (In case of displacement of the umbilicus by accumulation of fat, the measurement was taken at midpoint between the anterosuperior iliac spine and the lower rib cage) |

|

| Kuriyan et al (2011) | India | Children and adolescents aged 3 to 16 years (n=9,060) | Midpoint between the lower rib cage and the iliac crest | >75th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Brannsether et al (2011) | Norway | Children and adolescents aged 4 to 18 years (n=5,725) | Midpoint between the last rib and the upper iliac crest | >85th percentile (overweight) and >95th percentile (obesity) specific for age and gender |

| Poh et al (2011) | Malasia | Children and adolescents aged 6 to 16.9 years (n=16,203) | Midpoint between the last rib and the upper iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Mushtaq et al (2011) | Pakistan | Children and adolescents aged 5 to 12 years (n=1,860) | Midpoint between the last rib and the upper border of the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Hatipoglu et al (2013) | Turkey | Children aged 0 to 6 years (n=2,947) | Midpoint between the lower rib cage and the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

| Mederico et al (2013) | Venezuela | Children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years (n=919) | Midpoint between the costal border and the iliac crest | >90th percentile specific for age and gender |

The rationale for the use of WHR is that, for a given height, there is an acceptable degree of fat stored in the upper portion of the body.32 Among the studies evaluating this parameter in children, controversial results were observed. In the study by Sant'Anna et al,32 there was a strong correlation between the percentage of body fat and WHR of children aged 6-9 years of both genders, while Majcher et al33 found no correlation between these parameters in children. A good correlation with BMI was observed in schoolchildren of both genders in the study performed by Ricardo et al44 in southern Brazil, where it was suggested that WHR could be used as additional information to BMI/age to determine total and central adiposity, respectively.

When comparing the diagnostic quality of BMI, WC, and WHR in screening for obesity in children, Hubert et al45 concluded that WHR was not very effective to classify childhood obesity. In the study by Perez et al,46 with Venezuelan children and adolescents, the WHR also did not effectively identify fat distribution, as it did not provide adequate sensitivity and specificity.

Conversely, the study by Marrodán et al34 demonstrated that WHR was an effective method to predict relative adiposity in children and adolescents aged 6-14 years. Brambilla et al35 observed that, when compared to WC and BMI, WHR was the best predictor of adiposity in children and adolescents, suggesting that this parameter may be a useful substitute for measuring body fat when other measures are not available.

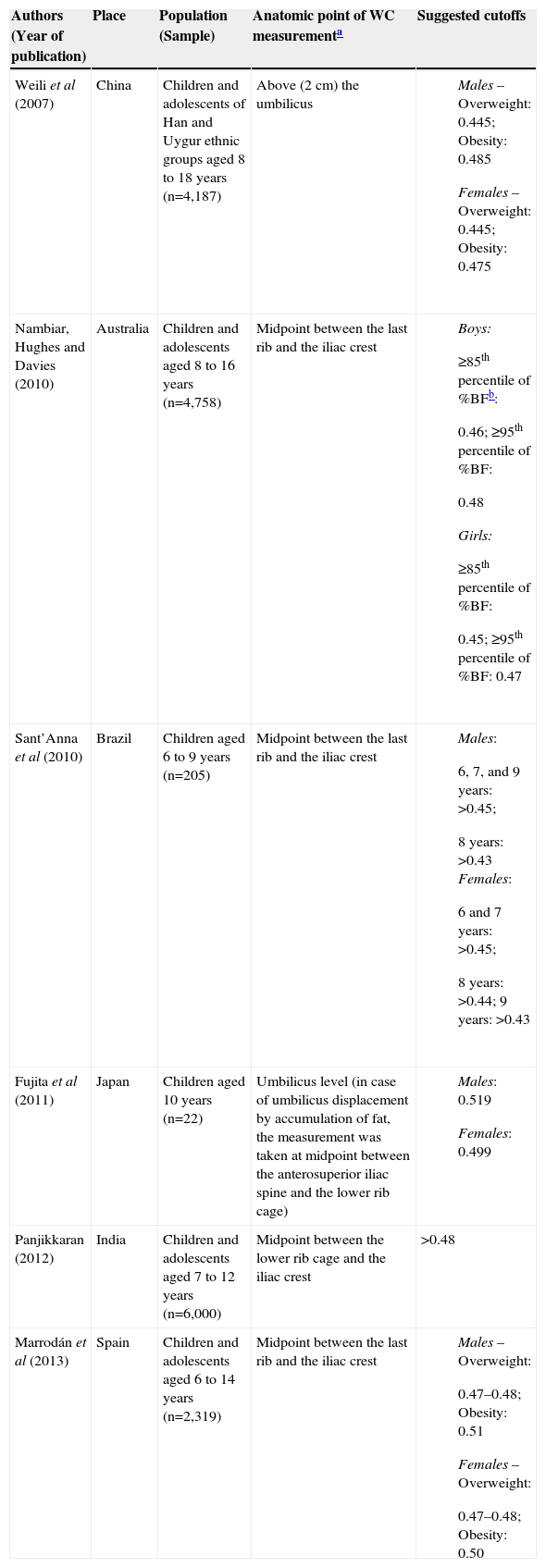

Considering the residual correlation between WHR (waist/height1) and height in children, studies have sought to investigate the dependence of this parameter on height and the influence of specific exponents on its predictive capacity to discriminate between children with different fat distribution.36–38 The value of 0.50 for the WHR has been established as the suitable cutoff for both adults and children.39,47,48 However, other values, most of them higher than 0.50, have been suggested to determine central obesity.

Regarding the methodological aspects, some studies used the classification of overweight/obesity by BMI according to the IOTF for the ROC curve analysis,34,40,41 while others considered the high percentage of body fat and upper body fat in relation to the study population, measured by bioelectrical impedance,32 DXA,49 and skinfold thickness42 as reference methods. There was also no agreement regarding the anatomical site for WC measurement, which leads to changes in WHR measurements. The cutoffs of these studies are presented in Table 3.

Cutoffs for waist/height ratio to identify children with overweight and obesity, as well as elevated body and trunk fat percentage

| Authors (Year of publication) | Place | Population (Sample) | Anatomic point of WC measurementa | Suggested cutoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weili et al (2007) | China | Children and adolescents of Han and Uygur ethnic groups aged 8 to 18 years (n=4,187) | Above (2 cm) the umbilicus |

|

| Nambiar, Hughes and Davies (2010) | Australia | Children and adolescents aged 8 to 16 years (n=4,758) | Midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest |

|

| Sant’Anna et al (2010) | Brazil | Children aged 6 to 9 years (n=205) | Midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest |

|

| Fujita et al (2011) | Japan | Children aged 10 years (n=22) | Umbilicus level (in case of umbilicus displacement by accumulation of fat, the measurement was taken at midpoint between the anterosuperior iliac spine and the lower rib cage) |

|

| Panjikkaran (2012) | India | Children and adolescents aged 7 to 12 years (n=6,000) | Midpoint between the lower rib cage and the iliac crest | >0.48 |

| Marrodán et al (2013) | Spain | Children and adolescents aged 6 to 14 years (n=2,319) | Midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest |

|

Regarding NC, there have been few studies evaluating this parameter as an indicator of adiposity in children. The retrieved studies demonstrated that this anthropometric measurement had good performance in determining overweight and obesity in children and adolescents.2,50–52 Significant positive correlations could be observed between NC and BMI in both genders, as well as high correlations with other indices, such as those that assess central obesity, WC,2,50–52 and arm circumference.50 However, a low correlation with the percentage of body fat was observed.50 In the study by Nafiu et al,51 NC appears to correlate better with BMI and WC in males than in females, and a stronger correlation was found between NC and other anthropometric indices in older children than in younger ones.

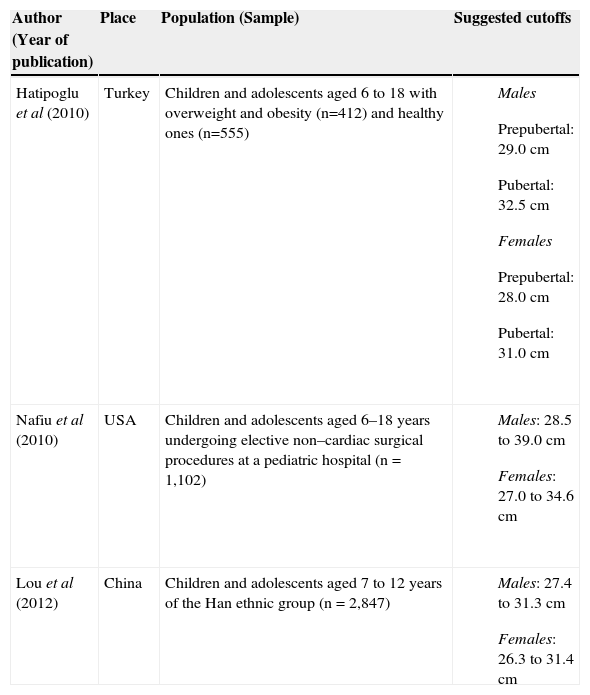

When evaluating a total of 4,581 Turkish children and adolescents from elementary and high schools in the city of Kayseri, Central Anatolia, Mazicioglu et al50 established mean, median, and percentile values of NC that can be used as preliminary data for future studies on body fat distribution. The NC cutoffs to identify overweight and obesity suggested by several studies are shown in Table 4. In all studies, NC was measured at the level of the thyroid cartilage; in contrast, the stratification of overweight/obesity by BMI used in the ROC analysis differed between the studies, which followed the classifications of the IOTF,50 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,51 and the Chinese Obesity Task Force,52 whereas other researchers2 used a local reference, explaining that references in stature can differ significantly between populations.

Neck circumference cutoffs to identify overweight and obese children

| Author (Year of publication) | Place | Population (Sample) | Suggested cutoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hatipoglu et al (2010) | Turkey | Children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 with overweight and obesity (n=412) and healthy ones (n=555) |

|

| Nafiu et al (2010) | USA | Children and adolescents aged 6–18 years undergoing elective non–cardiac surgical procedures at a pediatric hospital (n = 1,102) |

|

| Lou et al (2012) | China | Children and adolescents aged 7 to 12 years of the Han ethnic group (n = 2,847) |

|

According to what has been suggested by most studies, WC is an anthropometric measure that provides relevant information about body fat distribution, reflecting the degree of central adiposity in children. Some controversy could be explained by the study methodology, such as the work of Perez et al,46 which used the subscapular/triceps skinfold ratio as the reference method for ROC curve analysis. Although skinfold thickness is often used to estimate total body fat, there is considerable variability between individuals regarding subcutaneous thickness, tissue compressibility in a given location, and the ratio of several deposits of adipose tissue.54

It is worth mentioning that computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are considered the gold standard methods to assess body fat distribution, providing information about the morphological and anatomical location of different deposits (subcutaneous, visceral, and intermuscular adipose tissue). DXA, in turn, measures total fat with high accuracy and relatively low radiation, but does not differentiate between intra-abdominal and subcutaneous fat.54

Considering the significant differences observed among several studies in which the WC values were compared,18,19,22–24,29 it is important to establish reference values for WC in children, stratified by age and gender, that are specific for the population of several countries.

Currently, there is no consensus regarding the anatomical site where the WC should be measured. However, in a study of children aged 6-9 years-old, it was observed that the WC measured at midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest presented the best correlation with body fat percentage.27 Bosy-Westphal et al28 observed that, in children, WC values differed significantly according to the anatomical site of measurement. The smallest value was found when the measurement was performed below the last rib, and the highest value, above the iliac crest, whereas an intermediate value was found at midpoint between these sites.

In the study by Sant'Anna et al,27 the measurement performed on the umbilicus was statistically higher among females. Thus, the interpretation of differences in WC between studies of different populations should be performed with caution, considering that the measure may have been performed in different anatomical sites.

WHR is a simpler measure of health risk than other anthropometric indices in children, such as BMI/age, as it requires no adjustment for age and gender,43 having emerged as a central adiposity parameter and significant predictor of risk factors for cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. Ashwell and Hsieh6 proposed the use of WHR as a simple screening tool, considering its fast and effective measurement. They suggest that WHR is more sensitive, less expensive, and easier to measure and calculate than BMI.

Moreover, a value of 0.5 would indicate an increased risk for males and females of different ethnic groups, being applicable to adults and children. However, in a study of 5,725 Norwegian children and adolescents,48 the recommended cutoff of 0.5 showed high sensitivity and specificity to detect obesity in individuals aged 6-18 years; however, in younger children, this cutoff was not appropriate due to low specificity. The authors also suggest that, for overweight, the cutoffs should be different for children and adolescents aged 6-12 years and 12-18, and should not be defined for the younger age group.48

Due to the residual correlation between WHR and stature in children, the division of WC by height elevated to the power of 1 (waist/height1) may be insufficient to properly adjust the height during growth.36,37 Tybor et al36 evaluated a representative sample of children and adolescents aged 2-18 years of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), from 1999-2004, stratified by age and gender, and found a residual correlation between height and WHR between 0.29 and 0.36.

Conversely, the study by Taylor et al37 demonstrated that the simple division of the WC by height correctly discriminates, at least 90% of the time, children and adolescents with high and low levels of total and central fat.

The validity of WHR by the formula waist/height1 was evaluated by Nambiar et al38 in a cohort of 3,597 Australian children aged 5 to 17 years. The authors observed that WHR could be used in the study population, and was more appropriate than BMI due to its capacity to explain body fat distribution and the associated cardiovascular health risks. These findings indicate the need for further researches to investigate the degree of dependence of WHR with height and how this influences the association between central adiposity and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in this age group. Furthermore, it is necessary to evaluate whether the use of an exponent different from 1 can reduce bias and improve measurement accuracy.

Regarding the NC, despite the scarcity of studies in the literature that adopted this measurement, the results those that used it as a parameter to assess central adiposity in children indicate that such measurement may be a useful screening tool to identify overweight or obesity. It may also be useful to diagnose children at risk for high adiposity, an important predictor of cardiovascular health problems, especially when references adjusted for age and gender are available.2,51 The high correlations between NC and BMI may indicate that NC is a reliable index to determine obesity. Additionally, significant correlations between this parameter and other indicators of central obesity reflect the similarity between them.

The low correlation between the NC and the percentage of body fat, in turn, may mean that NC is a measure of disproportionate accumulation of fat instead of a general measure of obesity.50 A strong point in favor of the use of NC is that it has a good intra- and inter-rater reliability,53 and it is not necessary to perform multiple measurements to attain accuracy and reliability. Additionally, when compared to other indicators of upper body fat, NC measurement is simpler.

NC is a new parameter that has shown good results in the evaluation of children and can be used both in clinical practice and in epidemiological studies as a marker for central obesity. Special attention should be given to this parameter in children, as findings in researches conducted with infants have shown an association with cardiometabolic risk factors.7,55 However, further studies to evaluate the usefulness of NC as an indicator of adiposity are needed, and it is necessary to establish reference values for children at a younger age range.

It can be concluded that WC was the most often used parameter in studies, and has shown good performance in the assessment of central obesity, although the results of some studies are controversial. WHR has been proposed as a useful parameter to assess fat distribution in children, but some issues are worth investigating, such as a residual correlation with height during growth. NC, although a more recent measure and little studied so far, has proved to be satisfactory as a parameter to assess central adiposity in children.

The differentiated cutoffs for the different studied parameters may be due to ethnic differences, as well as the lack of standardization of the anatomical point used in the assessment of measures such as WC. Thus, new studies are necessary in order to further investigate the usefulness of these parameters in determining central obesity in childhood, including the standardization of the place where measures are to be taken and the determination of cutoffs that are comparable between different populations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.