To evaluate the influence of light exposure time on the adhesive strength and the failure mode of orthodontic brackets bonded to human enamel.

Methods100 metal brackets were bonded with Transbond XT to the enamel bucal surface of human premolars. The sample was randomly divided into 5 experimental groups (n=20) according to the light exposure time (2, 4, 6, 8 and 10s) and light cured with an LED-curing device (1600mW/cm2). The specimens were thermocycled (5–55°C, 500 cycles), stored in distilled water (37°C, 7 days) and tested in shear, using an Instron universal machine (1 KN, 1mm/min). Failure mode was classified according to the Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) using a stereomicroscope (20× magnification). Shear bond strength (SBS) data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc tests. The failure mode data were submitted to Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test, followed by Tukey post hoc tests to the ranks. A significance level of 5% was set for all data.

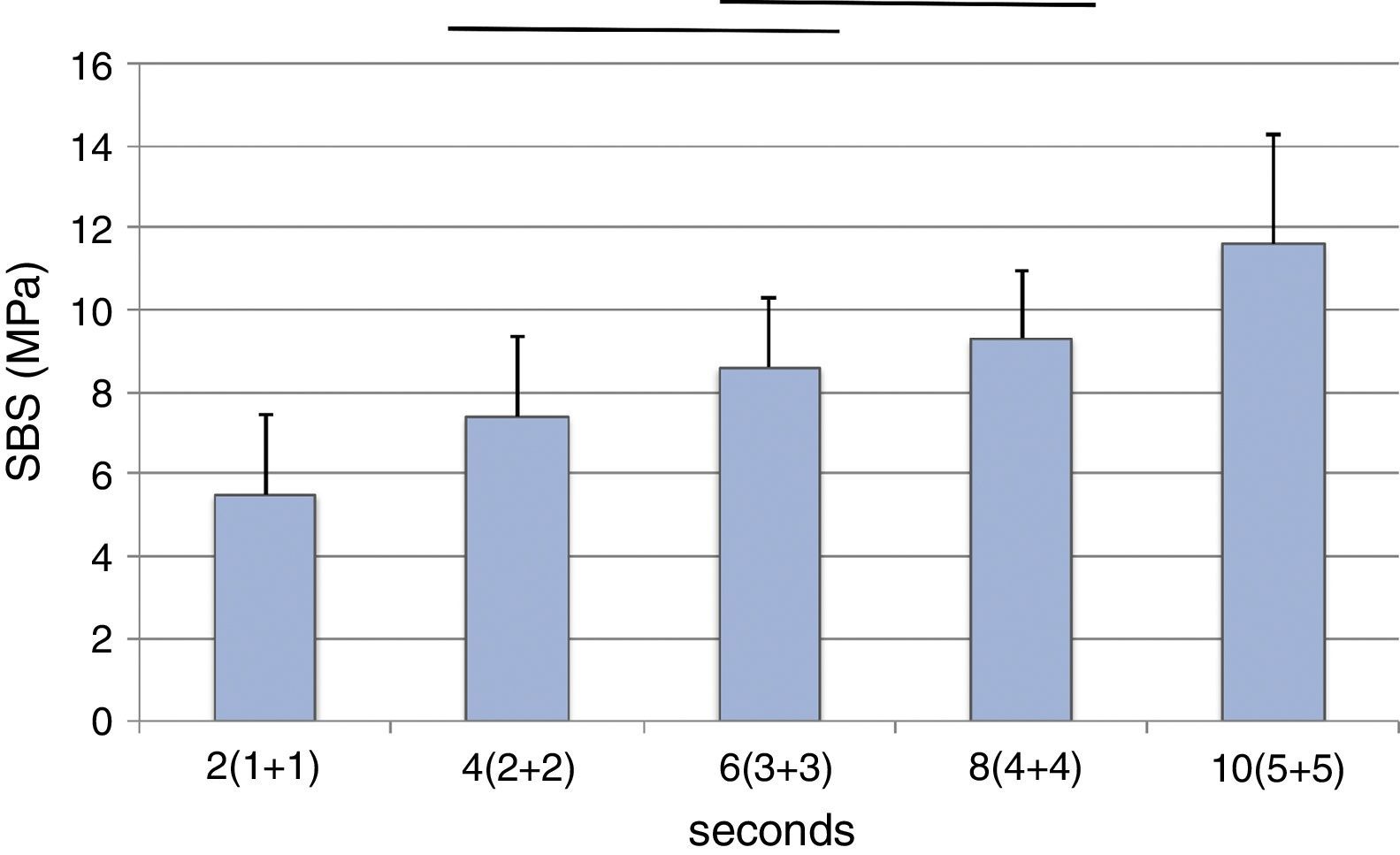

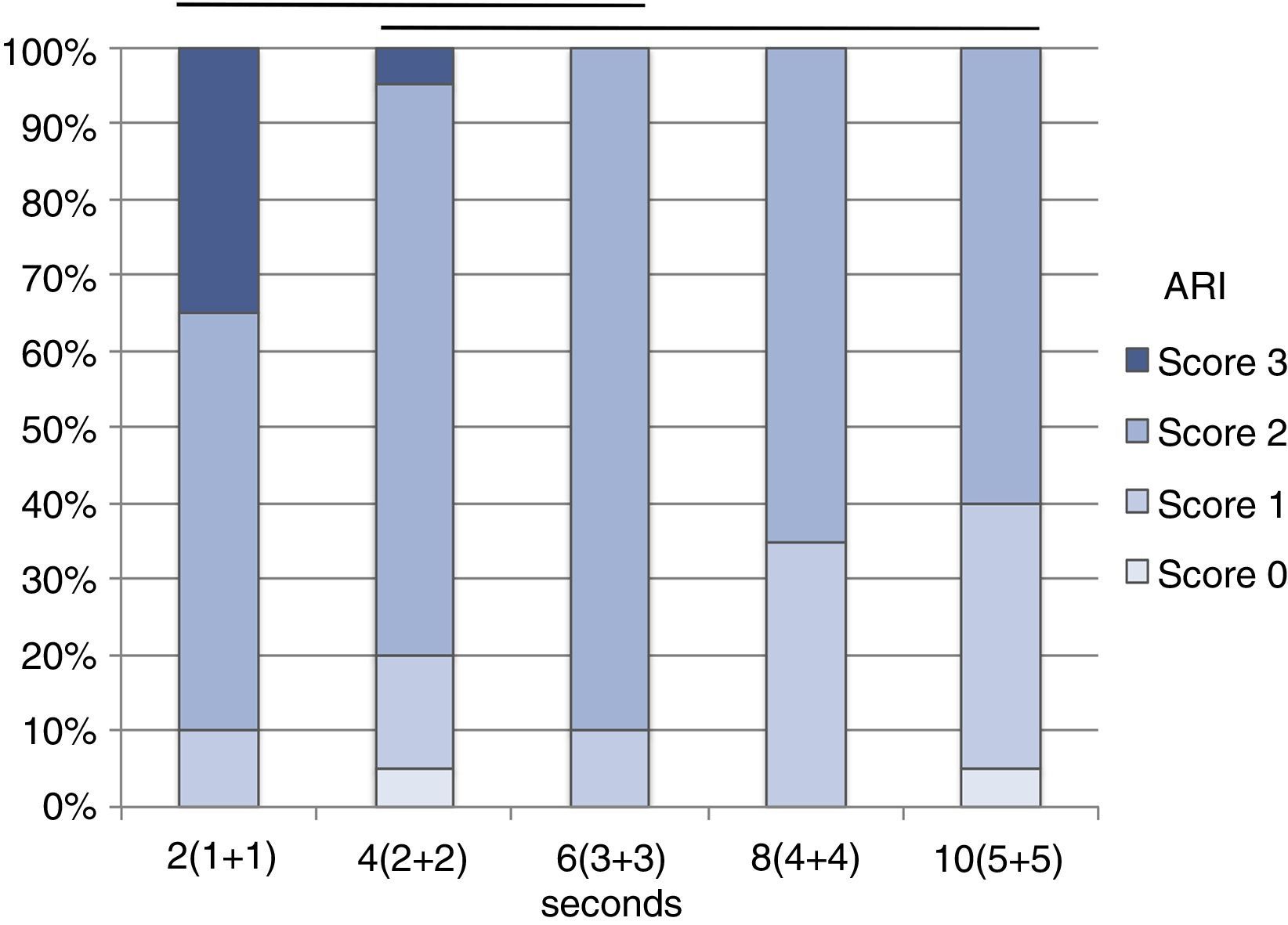

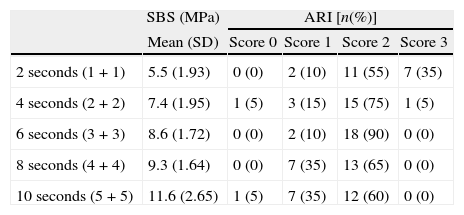

ResultsThe mean SBS values were 5.5±1.93MPa (2s), 7.4±1.95MPa (4s), 8.6±1.72MPa (6s), 9.3±1.64MPa (8s) and 11.6±2.65MPa (10s). Failure mode was mainly classified as Score 2. Both the SBS (p<0.001) and the failure mode (p=0.002) were statistically influenced by the exposure time.

ConclusionReducing the exposure time to less than 10s decreases the bracket bond strength. The weakest adhesive link was found at the bracket-adhesive interface.

Avaliar a influência do tempo de exposição na resistência adesiva e tipo de falha de brackets aplicados ao esmalte humano.

MétodosCem brackets metálicos foram colados com Transbond XT ao esmalte vestibular de pré-molares humanos. Os espécimes foram divididos aleatoriamente em 5 grupos experimentais (n=20) de acordo com o tempo de exposição à luz (2, 4, 6, 8 e 10 segundos) e fotopolimerizados com um aparelho LED (1.600mW/cm2). Após termociclagem (5–55°C, 500 ciclos) e armazenamento em água destilada (37°C, 7 dias), foi avaliada a resistência adesiva ao corte (SBS), com Instron (1 KN, 1mm/min). O tipo de falha foi classificado de acordo com o Índice de Adesivo Remanescente (ARI), utilizando estereomicroscópio (20x). Os dados de SBS foram analisados estatisticamente com ANOVA, seguida de comparações múltiplas segundo Tukey. O tipo de falha foi analisado com teste não paramétrico segundo Kruskal–Wallis seguido de comparações múltiplas às ordens segundo o método de Tukey. O nível de significância estatística foi fixado em 5%.

ResultadosOs valores médios de SBS foram de 5,5±1,93MPa (2 segundos), 7,4±1,95MPa (4 segundos), 8,6±1,72MPa (6 segundos), 9,3±1,64MPa (8 segundos) e 11,6±2,65MPa (10 segundos). O tipo de falha observado foi predominantemente classificado como Índice 2. Tanto a resistência adesiva (p<0.001) como o tipo de falha (p=0.002) foram estatisticamente influenciados pela variação do tempo de exposição.

ConclusõesA diminuição do tempo de exposição abaixo dos 10 segundos reduz a resistência adesiva dos brackets. O elo mais fraco da interface adesiva foi a união do adesivo ao bracket.

Light-cured bonding systems are widely used in orthodontic fixed appliance therapy, due to their ease of use, a better control of working time which facilitates accurate bracket placement and an easier removal of excess bonding material.1,2 However, light-cured orthodontic adhesives have some disadvantages, since a significant chairtime period is needed to expose each bracket to the light source.3,4 Additionally, there may be some difficulty in obtaining an adequate light cure under metal brackets that block the transmission of light.5

In orthodontic treatment, achieving an appropriate bond strength between the bracket and the tooth surface is essential, in order to minimize accidental debonding that can increase the costs and delay the treatment.6,7 Several factors that could affect the ability to promote proper bracket bond strength have been described.8–11 In spite of this, optimizing the composite resin physical and mechanical properties depends on reaching an adequate degree of cure, and the degree of cure of light-activated resins is directly related to the intensity of light and radiation exposure time.12,13 For an effective activation of the polymerization, the photo-initiator needs to be exposed to a certain amount of energy. The radiant exposure that is the total amount of energy supplied to the light-cured resin cement can be expressed by the product of light irradiance and exposure time.12,14 Since these two factors have been considered inversely proportional, in theory, the decrease of one could be compensated by increasing the other.15–17

As so, in order to reduce exposure time, and consequently clinical chairtime, several high-powered LED-curing devices, producing higher light intensity, have been developed.18–20

Initially, light cured orthodontic cements manufacturers recommended an exposure time to the light emitted by conventional halogen curing devices, with approximately 400YmW/cm2, of 20–40s per tooth.21 Also, according to manufacturers’ recommendations, the total exposure time should be equally divided in two periods, exposing the light over the mesial and distal surfaces of each bracket.

With the development of technology, new LED curing devices were launched on the market. In a first phase, these curing devices generated light with an intensity of approximately 800–1000YmW/cm2, reducing the required light exposure time to 10s.22–24 Currently, some high-powered LED-curing devices are able to emit a light radiation with intensity that approaches 1600–2000YmW/cm2, allowing shorter exposure times of 6s for metallic brackets.21

The objective of this study was to evaluate the influence of the exposure time to an high-powered LED on the adhesion promoted by a light cured orthodontic resin between metal brackets and human enamel, according to the following experimental hypotheses:

H0: Light exposure time does not influence the bracket shear bond strength.

H0: Light exposure time does not affect the failure mode.

Materials and methodsThe sample size (n=20) was assessed with a power analysis in order to provide a statistical significance of alpha=0.05 at 80% power.

One hundred non-carious human premolar teeth extracted for orthodontic reasons and without visible buccal defects and restorations were used. The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee and the teeth were collected after receiving verbal consent.

All the teeth were processed according to the technical specification ISO/TS 11405: 2003. After removing periodontal tissue remains and calculus, the teeth were immersed in 0.5% chloramine solution at 4°C over a week, and stored in distilled water at 4°C. Immediately before the bonding procedures, the buccal surfaces were cleaned with a green stone at low speed, rinsed with water spray and air-dried.

Enamel buccal surfaces were etched with a 35% phosphoric acid gel (Transbond XT Etching gel, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA) for 30s. After this procedure, the teeth were washed with water spray for 15s and air dried with oil-free compressed air for 5s. After checking the correct conditioning of the enamel, metal brackets [Victory SeriesTM Miniature Mesh Twin Bracket Univ U Bicus, .018 (0.46mm), +0° TQ 0° Ang, 3M Unitek], with a nominal base area of 10.61mm2, were bonded with Transbond XT (3M Unitek), applying a uniform layer of adhesive primer (Transbond XT Primer) on the etched enamel, and the resin cement (Transbond XT Light Cure Orthodontic Adhesive) on the base of the brackets. The brackets were immediately set in place and firmly pressed against the tooth surfaces. Excess cement was carefully removed with a dental probe, and the adhesive system was light cured (Ortholux Luminous Curing Light, 3M Unitek) with an output of 1600YmW/cm2 for a period of time according to the experimental group. The 100 specimens were randomly divided into 5 experimental groups (n=20). In all the groups, the total exposure time is the sum of two equal periods of time that the light was applied mesially and distally of the brackets. The light source was kept as close as possible at an angle of 45° to the adhesion interface. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the adhesive system used should be light cured for 6s (3s mesial+3s distal). The exposure times tested were 2 (1+1), 4 (2+2), 6 (3+3), 8 (4+4) and 10 (5+5) seconds. The light output was checked every 20 specimens, with a Demetron L.E.D. Radiometer (Kerr, Danbury, CT, USA).

The specimens were mounted in isobutyl methacrylate self-curing cylinders (Sample-Kwick, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA), thermocycled (5–55°C, 500 cycles), and stored in distilled water at 37°C, for 7 days.

Adhesive strength values were determined under shear forces on a universal testing machine (Instron model 4502, Instron Ltd., Bucks, England). The specimens were fixed in a standardized way on the testing machine, and a wire loop was applied under the gingival wings of the bracket, to induce gingival-oclusal shear stress at the adhesive interface. The tests were carried out at a crosshead speed of 1mm/min, using a load cell of 1kN. The load values were recorded in Newton (N) when failure occurred, and divided by the surface area of the bracket base to calculate the shear bond strength, expressed in MegaPascal (MPa).

After the failure, specimens were observed with a stereomicroscope (Meiji Techno, EMZ-8TR model, Meiji Techno Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan), at a 20× magnification. The failure mode was scored according to Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI)25: Score 0 – no adhesive remained on the tooth in the bonding area, corresponding to adhesive failure on the enamel–adhesive interface; Score 1 – less than 50% of the adhesive remained on the tooth; Score 2 – 50% or more of the adhesive remained on the tooth surface; Score 3 – 100% of the adhesive remained on the tooth, with a distinct impression of the bracket mesh, corresponding to failure on the bracket-adhesive system interface.

Data was statistically analyzed using a commercial software application (IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0.0 for Mac, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The normality and homoscedasticity was assessed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p=0.173) and Levene's (p=0.170) tests, and shear bond strength (SBS) data was analyzed with one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc tests. Failure mode data was submitted to Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric statistical test, followed by LSD post hoc tests to the failure ranks. Statistical significance was identified at alpha=0.05.

ResultsThe SBS mean values ranged from 5.5MPa, for the 2s experimental group, to 11.6MPa, observed in specimens light cured for 10s (Table 1). According to ANOVA, the SBS was statistically influenced (p<0.001) by the exposure time. The mean SBS value yielded in the 10s group was significantly higher than in all the other experimental groups (p<0.05), and the SBS observed with an exposure time of 2s was significantly lower (p<0.05) than with the further exposure times studied (Fig. 1).

Shear bond strength and Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) data.

| SBS (MPa) | ARI [n(%)] | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 | Score 3 | |

| 2 seconds (1+1) | 5.5 (1.93) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 11 (55) | 7 (35) |

| 4 seconds (2+2) | 7.4 (1.95) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 15 (75) | 1 (5) |

| 6 seconds (3+3) | 8.6 (1.72) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 18 (90) | 0 (0) |

| 8 seconds (4+4) | 9.3 (1.64) | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 13 (65) | 0 (0) |

| 10 seconds (5+5) | 11.6 (2.65) | 1 (5) | 7 (35) | 12 (60) | 0 (0) |

The distribution of the failure mode by the five experimental groups is presented in Table 1. The failure mode was predominantly classified as Score 2. Score 3, with 100% of the adhesive remaining on the tooth surface, was almost exclusively observed in the group of specimens light cured for 2s. The ARI was statistically (p=0.002) influenced by light exposure time (Fig. 2).

DiscussionDuring an orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances, orthodontic brackets are subjected to clinical stresses applied by orthodontic archwires, chewing forces or even iatrogenic stresses. Achieving an appropriate bracket bond strength is an issue of relevant clinical significance, in order to prevent accidental debonding.

In the present study, as SBS and failure mode were statistically influenced by the exposure time, the null hypotheses tested were rejected.

Some authors claim that the radiant exposure required to properly light cure a resin composite is constant and can be calculated by multiplying the intensity of the light by the exposure time.12,26 According to this concept, an exposure time of 1 second should be enough to yield the required radiant exposure, when curing devices with an output of 1600YmW/cm2 are used.14 However, in this investigation, an exposure time of 2s was shown to be insufficient to achieve proper bond strength. Despite the high intensity of the light, when too short exposure times are used, the energy supplied seems to be insufficient. Such unsatisfactory polymerization seems to be associated with a high free radical termination rate.26 Furthermore, metal brackets block the light, requiring a transmission mechanism that is provided by reflection in the tooth structure. The curing device tip is therefore applied to the edges of the brackets, with the light falling directly on the tooth surface that reflects it onto the adhesive system under the bracket. This procedure results in light absorption and scattering, reducing the light intensity and the amount of energy delivered to the resin cement.

In this study, a shorter light exposure time was related to a decrease in the adhesive mean values and a failure mode with a larger amount of resin remaining on the tooth. This fact suggests that, in this case, the weakest part of the bracket/tooth interface was the inadequate cohesive strength of the orthodontic cement near the bracket caused by an insufficient degree of cure. As light radiation is supplied by tooth reflection, the adhesive system in contact with the tooth is closer to the light source, and so, easier to cure.

SBS values should not be directly compared among different studies since they could be influenced by several experimental variables.6,9,10 However, it has been suggested, and widely accepted, that bond strengths lower than 6–8MPa are insufficient to resist to clinical stress.27 The SBS mean value of the experimental group with specimens’ light cured for 2s is lower than the mentioned acceptable limit, supporting the suggestion that such short period of time should not be used with 1600YmW/cm2 LED-curing devices.

On the other hand, whilst according with the manufacturers’ instructions, the orthodontic cement under metallic brackets should be light cured for 6s, increasing the exposure time to 10s led to higher bond strength. Analysing the failure mode, although no significant differences were found between these experimental groups, a tendency can be detected for an increase in failures classified as Scores 0 and 1 in the 10s group, which may show an increase in the cohesive strength of the orthodontic cement due to a more effective cure. As no enamel fractures during debonding were observed, and the SBS mean value was higher than that achieved in per manufacturer's instructions group, light curing this orthodontic cement with a curing device with 1600YmW/cm2 for two periods of 5s seems to be clinically acceptable and should be recommended.

ConclusionsWithin the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that both the SBS and the failure mode are influenced by the exposure times tested. Reduction of exposure time to less than 10s decreases the bracket bond strength.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

![Mean shear bond strengths (MPa) according to several experimental groups. [Horizontal line indicates statistical similar groups (p≥0.05)]. Mean shear bond strengths (MPa) according to several experimental groups. [Horizontal line indicates statistical similar groups (p≥0.05)].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/16462890/0000005500000002/v1_201407220031/S1646289014000272/v1_201407220031/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) scores distribution by experimental groups. [Horizontal line indicates statistical similar groups (p≥0.05)]. Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) scores distribution by experimental groups. [Horizontal line indicates statistical similar groups (p≥0.05)].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/16462890/0000005500000002/v1_201407220031/S1646289014000272/v1_201407220031/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)