To determine whether generic measures of disability, depression and physical activity are able to differentiate participants with and without pain.

Materials and methods504 adults aged ≥60 years old recruited at 18 primary care centers were assessed for: pain (NRS), disability (WHODAS), performance (SPPB), depressive symptoms (GDS) and physical activity (RAPA).

Results376 (74.6%) participants reported pain; pain sites most commonly reported were: low back (54.6%), knee (50.8%), shoulder (29.5%), hip (27.9%) and neck (24.7%). Pain was associated with increased disability, depression and decreased physical activity.

ConclusionsGeneric instruments were able to capture pain associated changes.

Explorar se instrumentos genéricos de funcionalidade, depressão e atividade física são capazes de diferenciar utentes com e sem dor.

Materiais e métodos504 pessoas com 60 ou mais anos dos cuidados de saúde primários foram avaliadas quanto a: dor (NRS), funcionalidade percebida (WHODAS), performance (SPPB), depressão (GDS) e atividade física (RAPA).

Resultados376 (74,6%) participantes referiram dor; os 5 segmentos corporais mais afetados foram: a lombar (54,6%), os joelhos (50,8%), os ombros (29,5%), a anca (27,9%) e a cervical (24,7%). A presença de dor estava associada a menor funcionalidade, depressão e menor atividade física.

ConclusõesInstrumentos genéricos são capazes de distinguir alterações associadas à dor.

Pain is highly prevalent in the general older adult population with bothersome pain in the last month affecting up to 52.9% of those aged 65 years or more.1 In the primary health care setting, one month prevalence of any pain was shown to be 66.2%2 and pain represents one in seven primary care consultations.3 Particular syndromes such as chronic low back pain or knee pain are the most common complaints with a prevalence of up to 23.0% and 41.0%, respectively.4,5 In addition, pain greatly interferes with daily life and the extend of this interference has been shown to have a more than twofold increase in the 80 years (35.0%) age group in relation to the 50 to 59 years age group (16.0%).2 Pain interferes with the normal performance of a range of activities including moving around, recreational activities, sleep, self-care, household activities and work and psychological functioning.6,7

Despite the considerable burden associated with pain in the primary care and its impact on self-reported disability and performance,8 relatively little is known about the characteristics of older adults with pain. To improve the understanding and management of a health condition, accurate information is needed regarding the patients’ characteristics and their clinical presentation.9 Previous studies have focused on specific pain syndromes such as low back pain or knee pain,4,9,10 but few have presented data from more than one pain syndrome or from physical activity and depression, which are important predictors of pain associated disability.8

Comprehensive assessment of patients in primary care is only feasible if instruments are easy to use in terms of the technical skills and specialized equipment required, are broadly applicable and appropriate for a range of age and cultural groups.11 Furthermore, the use of a pre-defined battery of tests that is routinely applied in a large group of patients and by different health professionals (e.g. doctors, physiotherapists or nurses) is likely to favor routine assessment and comparability of results. Therefore, the aims of this study are to (i) describe the characteristics of a sample of patients aged ≥60 years old attending primary care, in terms of pain, self-reported disability, performance, depression and physical activity and (ii) explore whether generic measures of self-reported disability (WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 – WHODAS 2.0), performance (Short Physical Performance Battery – SPPB), physical activity (Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity – RAPA) and depression (Geriatric Depression Scale – GDS) are able to differentiate between those with and those without pain at specific body sites. Each instrument takes less than 10min to complete and do not require specialized training or equipment, rendering them easy to use in primary care. Additionally, the SPPB and WHODAS 2.0 have been shown to be reliable and valid among several elderly populations that differ in terms of culture, language and education.12–14

Material and methodsThe present study refers to the cross sectional baseline analysis of a 12-month cohort study which aims to evaluate the association between disability and primary care consumption.

ParticipantsParticipants were older adults comprising a convenience sample and were recruited through primary health care practices, either by referral from health care practitioners or direct invitation by researchers, among those attending health services on the days of data collection. Participants were recruited from 18 primary care practices located across the Councils of Aveiro, Ílhavo and Vagos, Portugal. The number of participants from each council and health care practice was proportional to the population served and this was calculated as follows: (i) an a priori sample size calculation considering the total number of inhabitants from Aveiro, Ílhavo and Vagos aged 18 years old and over, a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 4% indicated that 504 participants would be needed; (ii) the total sample size calculated (n=504) was subdivided according to the percent contribution of each municipality, resulting in 259 participants from Aveiro, 147 participants from Ílhavo and 98 participants from Vagos. The number of participants assessed at each primary care practice within the same municipality was calculated based on the percentage of inhabitants served at each practice by sex and age group.

Participants could be enrolled in the study if they were ≥60 years old and were able to give written informed consent. This was ascertained by asking participants to explain on their own words what the study involved. Sixty years old was used as the cut off for older adults in line with the United Nations definition (http://www.unfpa.org/ageing).

The study received Ethical approval from the Regional Health Administration Commission, Coimbra, Portugal. All participants signed an informed consent prior to their participation.

ProceduresAll participants were interviewed once by a researcher at the primary health care center that the participant usually attended. All researchers involved in data collection were previously trained. Training included the presentation of instruments and methods of application, their application to participants not included in the study and posterior discussion of results. Data collection took place between March 2012 and March 2014. Demographic and health characteristics, aspects of pain, self-reported disability, performance, depressive symptoms and physical activity were assessed. The specific procedures and instruments used are specified below.

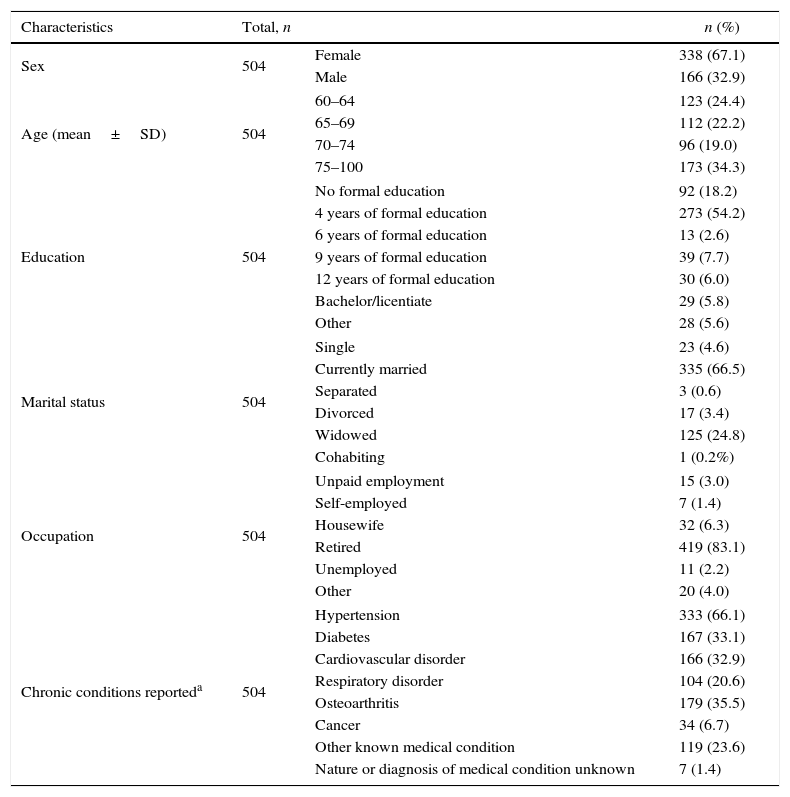

Demographic and health characteristicsDemographic and health characteristics included age, sex, years of formal education, occupation, marital status and presence of chronic disorders. The presence of the latest was ascertained by asking participants whether they had any of the following conditions: (i) hypertension, (ii) diabetes, (iii) cardiovascular disorders, (iv) respiratory disorders, (v) cancer, (vi) osteoarthritis (back, hip or knee), (vii) other known medical condition or (viii) any medical condition for which the nature/medical diagnosis was not known. The total number of reported chronic conditions was counted. The categorization of comorbidities based on number of comorbidities has been used in previous studies.6,15

Pain intensity, frequency, duration and number of pain sitesPain assessment in clinical practice is essential for older people and requires the use of instruments that are easy and simple to understand.16 Published guidelines for pain assessment in older people recommend the use of a vertical numeric graphic rating scale and of a body chart for the assessment of pain intensity and location, respectively.16 In the present study, global pain intensity (pain intensity considering all the pain sites) in the day of data collection was measured using a 10cm vertical numeric graphic rating scale, with 0 for no pain and 10 for the most severe pain imaginable. Participants were also asked to mark on a body chart where they felt pain in the preceding week. The body segments were participants reported pain were identified and the number of pain sites was counted and categorized as (1) single pain site, (2) two pain sites, (3) 3 or more pain sites but not meeting the criteria for widespread pain and (4) widespread pain. Widespread pain was defined as pain in the left and right side of the body, pain above and below the waist and axial-skeletal pain.17 Both the numeric rating scale and the body chart have been shown to be valid and reliable in older people.18,19 Body segments with pain were also identified. In addition, pain frequency and duration were also assessed using two forced choice questions. Pain frequency during the week before the interview was assessed by asking participants to choose one of the following options: (1) seldom (once a week), (2) occasionally (2 to 3 times a week), (3) often (more than 3 times a week) or (4) always (all days). This was transformed into a two level variable for analysis: (1) pain seldom or occasionally and (2) pain often or always. To characterize pain duration participants were asked for how long they felt pain and answers were categorized as (1) <6 months and (2) ≥6 months.

Self-reported disabilitySelf-reported disability was assessed using the Portuguese version of the 12-item interview administered version of WHODAS 2.0, which is valid and reliable.20 The WHODAS 2.0 is a disability assessment instrument based on the conceptual framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health with a recall period of 30 days and provides a global measure of disability.12 WHODAS 2.0 scores were computed according to the simple scoring method as indicated in the manual.12 This included summing the scores assigned to each of the 12 items – “none” (1), “mild” (2), moderate (3), severe (4) and extreme (5). The sum score for global disability therefore ranged from 0 (no disability) to 60 (complete disability), with higher scores indicating higher levels of disability.

Performance-based disabilityPerformance-based disability was assessed using the SPPB.21 SPPB total score is a composite score based on the individual scores of three timed tasks: the ability to stand with the feet side by side/semitandem/tandem for 10s (balance), usual walking speed (calculated over 3 meters), and the ability to rise from a chair as quickly as possible for five consecutive times. Each of the three performance measures was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating the inability to complete the test and 4 indicating the highest level of performance. A summary score (range 0–12) was subsequently calculated by adding the scores of each individual test. Higher scores reflect higher levels of function.21

Depressive symptomsDepressive symptoms were assessed using the short version of the Portuguese translation of the GDS,22 a valid and reliable 15 item self-report scale of depression initially developed for adults aged 65 years or more.23 However, a more recent study24 showed that its level of sensitivity and specificity for patients aged less than 65 is comparable to that of patients aged more than 65 years. Therefore, GDS was adopted in this study. Participants are asked to respond by answering yes or no to each of the 15 items: 10 items indicate the presence of depression when answered positively and 5 indicate depression when answered negatively. For the comparative analysis we used the GDS total score and for descriptive purposes we dichotomized the results as (1) no depressive symptoms (4 points or less) and (2) depressive symptoms (5 points or more).24

Physical activityPhysical activity was assessed using the Portuguese version of the RAPA questionnaire.25,26 This questionnaire was specifically designed for use with older people and has 9 items (7+2) with response options of yes or no. The total score of the first seven items is from 1 to 7 points, with the respondent's score categorized into one of five levels of physical activity: (1) sedentary (item 1: I rarely or never do any physical activities), (2) underactive (item 2: I do some light or moderate physical activities, but not every week), (3) regular underactive, light activities (item 3: I do some light physical activity every week), (4) regular underactive (item 4: I do moderate physical activities every week, but less than 30min a day or 5 days a week; and item 5: I do vigorous physical activities every week, but less than 20min a day or 3 days a week), and (5) regular active (items 6: I do 30min or more a day of moderate physical activities, 5 or more days a week; and item 7: I do 20min or more a day of vigorous physical activities, 3 or more days a week). The last 2 items are about strength training and flexibility and are scored separately for individuals that reach the item 7 only as: (1) strength training, (2) flexibility or (3) both.25 Comparative analysis was performed using the levels of physical activity reported by participants. Additionally, count and proportion of those achieving and not achieving recommended levels of physical activity were also reported. Recommended levels were defined as moderate to moderately vigorous aerobic (endurance) activity, with a total weekly volume of 150–180min/wk.27

Statistical analysisThe Predictive Analytics Software (PAWS software, IBM, New York) (formerly SPSS Statistics) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample in terms of age, sex, years of formal education, occupation, marital status, chronic conditions, depression, WHODAS 2.0 scores, SPPB scores, RAPA scores, and pain characteristics for participants without pain, for those with pain and considering the five most reported body sites with pain. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables and count and proportion were reported for categorical variables. The Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare RAPA scores between groups (no pain vs. pain at a specific location vs. pain elsewhere) and One Way ANOVAS for the remaining comparisons (age, years of formal education, number of comorbidities, WHODAS and SPPB scores). The Bonferroni test was used for post hoc comparisons. Level of significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsSample characteristicsA total of 504 (338 females and 166 males) participants aged (mean±SD) 70.9±7.5 years entered the study. A detailed characterization of the sample is presented in Table 1.

Sample characteristics (n=504).

| Characteristics | Total, n | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 504 | Female | 338 (67.1) |

| Male | 166 (32.9) | ||

| Age (mean±SD) | 504 | 60–64 | 123 (24.4) |

| 65–69 | 112 (22.2) | ||

| 70–74 | 96 (19.0) | ||

| 75–100 | 173 (34.3) | ||

| Education | 504 | No formal education | 92 (18.2) |

| 4 years of formal education | 273 (54.2) | ||

| 6 years of formal education | 13 (2.6) | ||

| 9 years of formal education | 39 (7.7) | ||

| 12 years of formal education | 30 (6.0) | ||

| Bachelor/licentiate | 29 (5.8) | ||

| Other | 28 (5.6) | ||

| Marital status | 504 | Single | 23 (4.6) |

| Currently married | 335 (66.5) | ||

| Separated | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Divorced | 17 (3.4) | ||

| Widowed | 125 (24.8) | ||

| Cohabiting | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Occupation | 504 | Unpaid employment | 15 (3.0) |

| Self-employed | 7 (1.4) | ||

| Housewife | 32 (6.3) | ||

| Retired | 419 (83.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 11 (2.2) | ||

| Other | 20 (4.0) | ||

| Chronic conditions reporteda | 504 | Hypertension | 333 (66.1) |

| Diabetes | 167 (33.1) | ||

| Cardiovascular disorder | 166 (32.9) | ||

| Respiratory disorder | 104 (20.6) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 179 (35.5) | ||

| Cancer | 34 (6.7) | ||

| Other known medical condition | 119 (23.6) | ||

| Nature or diagnosis of medical condition unknown | 7 (1.4) | ||

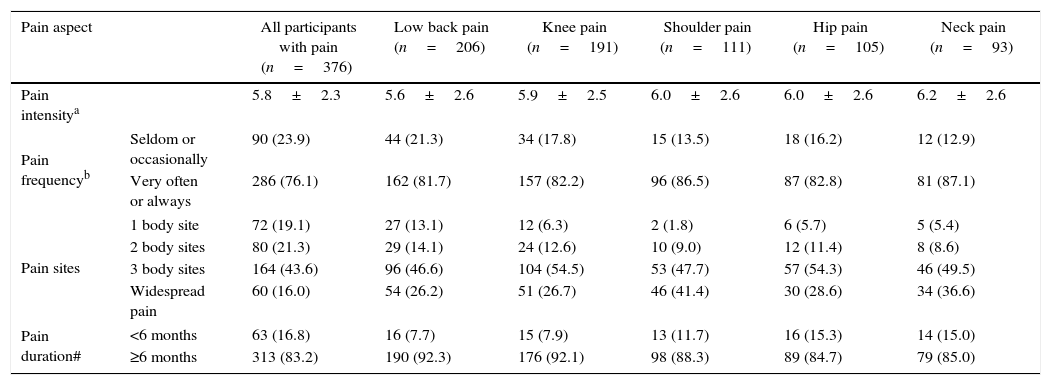

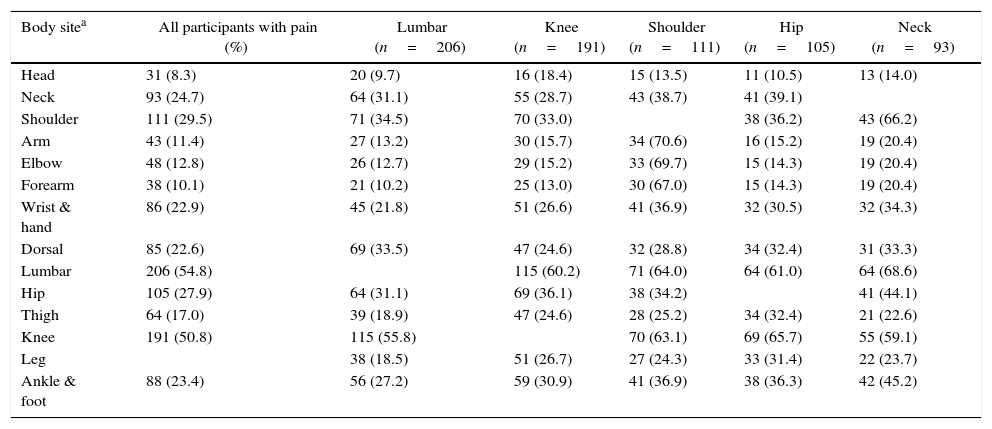

A total of 376 (74.6%) participants reported pain in at least one body site during the week preceding data collection. Mean global pain intensity at the time of data collection was 5.8±2.3. In general, most participants had multisite or widespread pain (224; 59.6%), that was present for ≥6 months (313; 83.2%) and very often or always present (286; 76.5%) (Table 2). The five pain sites most commonly reported were: low back (54.8%), knee (50.8%), shoulder (29.5%), hip (27.9%) and neck (24.7%) and for this reason these groups were used in the comparative analysis. When considering participants reporting pain at each of these five body sites, results show that pain at multiple locations is present independently of the specific pain location considered (low back, knee, shoulder, hip or neck). The percentage of patients reporting one pain site only, varied between 1.8% for those reporting shoulder pain and 13.1% for those reporting low back pain. The percentage of patients with widespread pain varied between 26.7% in the group of participants with knee pain and 41.4% in the group of participants with shoulder pain (Table 3). Global mean pain intensity was quite similar across the five pain syndromes considered. Pain very often or always was reported by a percentage of patients that varied between 81.7% (low back pain) and 87.1% (neck pain) and pain for 6 months or more was reported by a percentage of patients that varied between 84.7% (hip pain) and 92.3 (low back pain).

Pain characteristics for the total number of participants with pain and when considering the five most common complaints.

| Pain aspect | All participants with pain (n=376) | Low back pain (n=206) | Knee pain (n=191) | Shoulder pain (n=111) | Hip pain (n=105) | Neck pain (n=93) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensitya | 5.8±2.3 | 5.6±2.6 | 5.9±2.5 | 6.0±2.6 | 6.0±2.6 | 6.2±2.6 | |

| Pain frequencyb | Seldom or occasionally | 90 (23.9) | 44 (21.3) | 34 (17.8) | 15 (13.5) | 18 (16.2) | 12 (12.9) |

| Very often or always | 286 (76.1) | 162 (81.7) | 157 (82.2) | 96 (86.5) | 87 (82.8) | 81 (87.1) | |

| Pain sites | 1 body site | 72 (19.1) | 27 (13.1) | 12 (6.3) | 2 (1.8) | 6 (5.7) | 5 (5.4) |

| 2 body sites | 80 (21.3) | 29 (14.1) | 24 (12.6) | 10 (9.0) | 12 (11.4) | 8 (8.6) | |

| 3 body sites | 164 (43.6) | 96 (46.6) | 104 (54.5) | 53 (47.7) | 57 (54.3) | 46 (49.5) | |

| Widespread pain | 60 (16.0) | 54 (26.2) | 51 (26.7) | 46 (41.4) | 30 (28.6) | 34 (36.6) | |

| Pain duration# | <6 months | 63 (16.8) | 16 (7.7) | 15 (7.9) | 13 (11.7) | 16 (15.3) | 14 (15.0) |

| ≥6 months | 313 (83.2) | 190 (92.3) | 176 (92.1) | 98 (88.3) | 89 (84.7) | 79 (85.0) | |

Percentage of participants with pain per body site for the total number of participants with pain and when considering the five most common complaints.

| Body sitea | All participants with pain (%) | Lumbar (n=206) | Knee (n=191) | Shoulder (n=111) | Hip (n=105) | Neck (n=93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | 31 (8.3) | 20 (9.7) | 16 (18.4) | 15 (13.5) | 11 (10.5) | 13 (14.0) |

| Neck | 93 (24.7) | 64 (31.1) | 55 (28.7) | 43 (38.7) | 41 (39.1) | |

| Shoulder | 111 (29.5) | 71 (34.5) | 70 (33.0) | 38 (36.2) | 43 (66.2) | |

| Arm | 43 (11.4) | 27 (13.2) | 30 (15.7) | 34 (70.6) | 16 (15.2) | 19 (20.4) |

| Elbow | 48 (12.8) | 26 (12.7) | 29 (15.2) | 33 (69.7) | 15 (14.3) | 19 (20.4) |

| Forearm | 38 (10.1) | 21 (10.2) | 25 (13.0) | 30 (67.0) | 15 (14.3) | 19 (20.4) |

| Wrist & hand | 86 (22.9) | 45 (21.8) | 51 (26.6) | 41 (36.9) | 32 (30.5) | 32 (34.3) |

| Dorsal | 85 (22.6) | 69 (33.5) | 47 (24.6) | 32 (28.8) | 34 (32.4) | 31 (33.3) |

| Lumbar | 206 (54.8) | 115 (60.2) | 71 (64.0) | 64 (61.0) | 64 (68.6) | |

| Hip | 105 (27.9) | 64 (31.1) | 69 (36.1) | 38 (34.2) | 41 (44.1) | |

| Thigh | 64 (17.0) | 39 (18.9) | 47 (24.6) | 28 (25.2) | 34 (32.4) | 21 (22.6) |

| Knee | 191 (50.8) | 115 (55.8) | 70 (63.1) | 69 (65.7) | 55 (59.1) | |

| Leg | 38 (18.5) | 51 (26.7) | 27 (24.3) | 33 (31.4) | 22 (23.7) | |

| Ankle & foot | 88 (23.4) | 56 (27.2) | 59 (30.9) | 41 (36.9) | 38 (36.3) | 42 (45.2) |

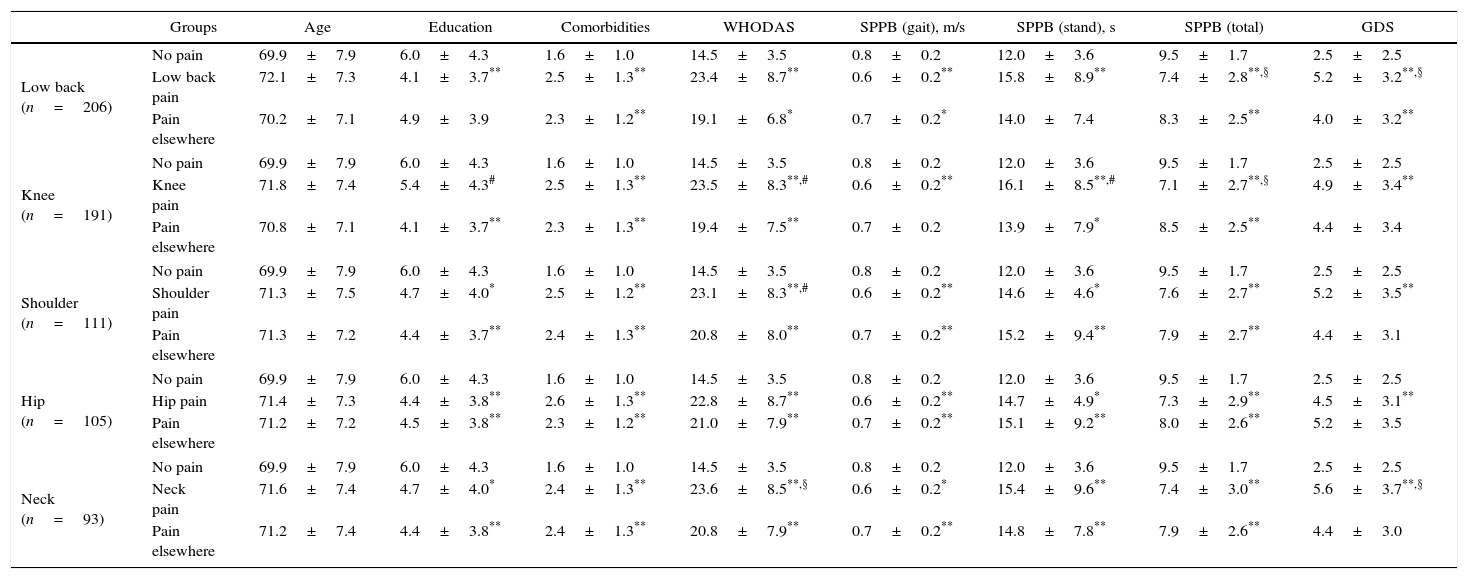

Overall, participants reporting pain at the body sites considered (low back, knee, shoulder, hip and neck) showed significantly higher levels of self-reported disability, took longer to walk 3m and to perform the chair stands and scored lower in the SPPB when compared to those without pain (Table 4). Additionally, participants with pain failed the balance test more often than those without pain (Pearson chi-square≤0.001; able to complete test adjusted residuals: “no pain” group=3.6; “pain elsewhere” group – between 0.4 and −2.5; pain at specific locations group – between −0.8 and −3.7). When comparing those reporting pain at a specific body site with those reporting pain elsewhere, participants with low back pain were found to score lower in the SPPB than those reporting pain elsewhere; participants with knee pain showed higher self-reported and performance based disability and took more time to perform chair stands than those with pain elsewhere; participants with shoulder pain and neck pain showed higher levels of self-reported disability than those with pain elsewhere. Overall, results seem to suggest that both WHODAS and SPPB are able to capture pain associated disability independently of pain location.

Multiple comparisons between participants with no pain, those with pain at a specific body site (low back, knee, shoulder, hip and neck) and those with pain in sites other than the one specified for: age, education, number of comorbidities and WHODAS 2.0, SPPB and GDS scores.

| Groups | Age | Education | Comorbidities | WHODAS | SPPB (gait), m/s | SPPB (stand), s | SPPB (total) | GDS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low back (n=206) | No pain | 69.9±7.9 | 6.0±4.3 | 1.6±1.0 | 14.5±3.5 | 0.8±0.2 | 12.0±3.6 | 9.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.5 |

| Low back pain | 72.1±7.3 | 4.1±3.7** | 2.5±1.3** | 23.4±8.7** | 0.6±0.2** | 15.8±8.9** | 7.4±2.8**,§ | 5.2±3.2**,§ | |

| Pain elsewhere | 70.2±7.1 | 4.9±3.9 | 2.3±1.2** | 19.1±6.8* | 0.7±0.2* | 14.0±7.4 | 8.3±2.5** | 4.0±3.2** | |

| Knee (n=191) | No pain | 69.9±7.9 | 6.0±4.3 | 1.6±1.0 | 14.5±3.5 | 0.8±0.2 | 12.0±3.6 | 9.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.5 |

| Knee pain | 71.8±7.4 | 5.4±4.3# | 2.5±1.3** | 23.5±8.3**,# | 0.6±0.2** | 16.1±8.5**,# | 7.1±2.7**,§ | 4.9±3.4** | |

| Pain elsewhere | 70.8±7.1 | 4.1±3.7** | 2.3±1.3** | 19.4±7.5** | 0.7±0.2 | 13.9±7.9* | 8.5±2.5** | 4.4±3.4 | |

| Shoulder (n=111) | No pain | 69.9±7.9 | 6.0±4.3 | 1.6±1.0 | 14.5±3.5 | 0.8±0.2 | 12.0±3.6 | 9.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.5 |

| Shoulder pain | 71.3±7.5 | 4.7±4.0* | 2.5±1.2** | 23.1±8.3**,# | 0.6±0.2** | 14.6±4.6* | 7.6±2.7** | 5.2±3.5** | |

| Pain elsewhere | 71.3±7.2 | 4.4±3.7** | 2.4±1.3** | 20.8±8.0** | 0.7±0.2** | 15.2±9.4** | 7.9±2.7** | 4.4±3.1 | |

| Hip (n=105) | No pain | 69.9±7.9 | 6.0±4.3 | 1.6±1.0 | 14.5±3.5 | 0.8±0.2 | 12.0±3.6 | 9.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.5 |

| Hip pain | 71.4±7.3 | 4.4±3.8** | 2.6±1.3** | 22.8±8.7** | 0.6±0.2** | 14.7±4.9* | 7.3±2.9** | 4.5±3.1** | |

| Pain elsewhere | 71.2±7.2 | 4.5±3.8** | 2.3±1.2** | 21.0±7.9** | 0.7±0.2** | 15.1±9.2** | 8.0±2.6** | 5.2±3.5 | |

| Neck (n=93) | No pain | 69.9±7.9 | 6.0±4.3 | 1.6±1.0 | 14.5±3.5 | 0.8±0.2 | 12.0±3.6 | 9.5±1.7 | 2.5±2.5 |

| Neck pain | 71.6±7.4 | 4.7±4.0* | 2.4±1.3** | 23.6±8.5**,§ | 0.6±0.2* | 15.4±9.6** | 7.4±3.0** | 5.6±3.7**,§ | |

| Pain elsewhere | 71.2±7.4 | 4.4±3.8** | 2.4±1.3** | 20.8±7.9** | 0.7±0.2** | 14.8±7.8** | 7.9±2.6** | 4.4±3.0 | |

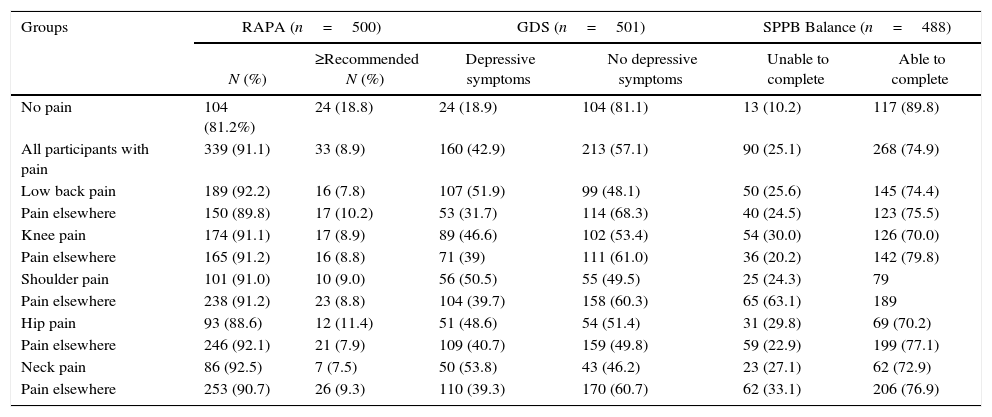

Participants in all pain groups (the specific condition pain groups and the “pain elsewhere” groups) showed significantly higher scores in the GDS, consistent with more depressive symptoms, than the “no pain” group. In addition, participants with low back and neck pain showed significantly higher scores in the GDS than participants with pain elsewhere. Percentage of patients with and without depression is presented in Table 5.

Percentage of participants achieving the recommended level of physical activity and percentage of participants reporting depressive symptoms per group (no pain, pain at a specific body site and pain elsewhere).

| Groups | RAPA (n=500) | GDS (n=501) | SPPB Balance (n=488) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N (%) | ≥Recommended N (%) | Depressive symptoms | No depressive symptoms | Unable to complete | Able to complete | |

| No pain | 104 (81.2%) | 24 (18.8) | 24 (18.9) | 104 (81.1) | 13 (10.2) | 117 (89.8) |

| All participants with pain | 339 (91.1) | 33 (8.9) | 160 (42.9) | 213 (57.1) | 90 (25.1) | 268 (74.9) |

| Low back pain | 189 (92.2) | 16 (7.8) | 107 (51.9) | 99 (48.1) | 50 (25.6) | 145 (74.4) |

| Pain elsewhere | 150 (89.8) | 17 (10.2) | 53 (31.7) | 114 (68.3) | 40 (24.5) | 123 (75.5) |

| Knee pain | 174 (91.1) | 17 (8.9) | 89 (46.6) | 102 (53.4) | 54 (30.0) | 126 (70.0) |

| Pain elsewhere | 165 (91.2) | 16 (8.8) | 71 (39) | 111 (61.0) | 36 (20.2) | 142 (79.8) |

| Shoulder pain | 101 (91.0) | 10 (9.0) | 56 (50.5) | 55 (49.5) | 25 (24.3) | 79 |

| Pain elsewhere | 238 (91.2) | 23 (8.8) | 104 (39.7) | 158 (60.3) | 65 (63.1) | 189 |

| Hip pain | 93 (88.6) | 12 (11.4) | 51 (48.6) | 54 (51.4) | 31 (29.8) | 69 (70.2) |

| Pain elsewhere | 246 (92.1) | 21 (7.9) | 109 (40.7) | 159 (49.8) | 59 (22.9) | 199 (77.1) |

| Neck pain | 86 (92.5) | 7 (7.5) | 50 (53.8) | 43 (46.2) | 23 (27.1) | 62 (72.9) |

| Pain elsewhere | 253 (90.7) | 26 (9.3) | 110 (39.3) | 170 (60.7) | 62 (33.1) | 206 (76.9) |

Participants in all pain groups (the specific condition pain groups and the “pain elsewhere” groups) showed significantly less physical activity than the “no pain” group (Pearson chi-square ≤0.01; equal or above recommended physical activity levels adjusted residuals: “no pain” group=3; pain groups ≥−2). Percentage of participants achieving the recommended levels of physical activity varied between 7.5% and 11.4% across the specific condition pain groups and was 18.8% in the “no pain” group (Table 5).

DiscussionFirstly, the results of this study show that most patients reporting low back pain, knee pain, shoulder pain, hip pain and neck pain also report pain at other body sites. Secondly, general measures of self-reported disability (WHODAS 2.0) and performance (SPPB) seem to be able to capture pain associated disability independently of pain location as they were able to differentiate between individuals with low back pain, knee pain, shoulder pain, hip pain and neck pain and those without pain. The same applies to the general measures of physical activity (RAPA) and depression (GDS). Additionally, individuals presenting with each of these specific pain syndromes seem to have similar age, education, number of comorbidities, self-reported disability, performance, depressive symptoms and level of physical activity when compared to individuals reporting pain elsewhere. Nevertheless, we did not perform statistical comparisons between groups with different pain syndromes and, therefore, it needs to be explored in future studies. Taken together, this study results suggest that specific painful syndromes do not tend to occur in isolation and are associated with increased disability, decreased levels of physical activity and increased levels of depression, which could be captured by generic instruments.

We found that the five most commonly reported pain body sites were: low back (54.8%), knee (24.8%), shoulder (29.5%), hip (27.9%) and neck (24.7%). Despite differences in body site pain prevalence, the first four body sites were also the body sites most commonly reported by Patel et al.,1 in a community based survey (back=30.3%, knee=24.8%, shoulder=19.9%, hip=17.7%). The neck (16.0%) occupied the 7th place after the foot (17.7%) and the hand (16.8%). Differences in prevalence values might be explained by the settings were studies took place (community vs. primary care centers). We also found that 19.0% of the participants reported pain in one body site only and 16.0% reported widespread pain. The percentage for single body site pain is even lower when considering only those with low back, knee, shoulder, hip or neck pain (between 1.8% and 13.1%), while the percentage of widespread pain is higher (between 26.2% and 41.4). Carnes et al.28 in a community based study with younger participants (mean age 52 years old) has shown that only 14% or less of those reporting chronic pain have it in a single site and that 33% had widespread pain. Viniol et al.,29 conducted a study with 647 patients with low back pain at primary care and reported that a quarter had widespread pain. These figures are similar to those found in the present study for the group of patients with low back pain (26.0%). Croft et al.,4 in a sample of almost 9000 participants aged 50 years old or more and registered with 3 general practices reported that 57.0% of those with knee pain reported at least pain in to other body regions. This percentage is also similar to that found in the present study (54.0%).

Mean SPPB scores (no pain=9.5±1.7; pain groups=between 7.1±2.7 and 8.5±2.5) and mean WHODAS 2.0 scores (no pain=14.5±3.5; pain groups=between 19.1±6.8 and 23.6±8.5) found in this study are similar to those previously reported in the literature for older adults aged 65 years or more. Cecchi et al.,30 in a sample of 120 community older adults with hip pain and 886 without hip pain reported mean (±SD) SPPB scores of 8.7±3.3 and 9.8±3.1, respectively. In the same study, mean (±SD) SPPB scores in 225 participants with knee pain was 8.9±3.3 and was 9.9±3.1 in a sample of 781 participants without knee pain. Bean et al.,31 assessed 137 older adults with limited mobility and reported mean (±SD) SPPB scores of 8.7±1.5. Gomes et al.,32 assessed 313 older adults who lived in the community and presented SPPB results separately for those participants with depressive symptoms (mean±SD=7.4±2.9) and without depressive symptoms (mean±SD=8.9±2.4). Sousa et al.,33 assessed older people living in seven low-and middle-income countries (urban sites in Cuba, Dominican Republic and Venezuela, and rural and urban sites in Mexico, Peru, China and India). The sample size for each country varied between 2000 and 3000 participants and mean (±SD) WHODAS 2.0 scores varied between 15.7±15.4 and 33.2±28.9.

The low percentage of participants that achieved recommended levels of physical activity even in the group that reported no pain (18.8%) and the fact that those in the pain groups, independently of the body site, showed lower levels of physical activity than those without pain highlight the need of strategies to improve physical activity levels as a means of preventing disability and improve health in general. A systematic review on the relationship between functional independence and physical activity recommends physical activity above baseline “normal” daily activity levels at an intensity of moderate to moderately vigorous aerobic (endurance) activity, with a total weekly volume of 150–180min/wk. This physical activity would translate to a >30% decrease in the relative risk of morbidity and mortality, and loss of independence, and further benefit would accrue with greater physical activity and greater fitness gains.27 Another systematic review aiming to establish global levels of physical activity among older people34 reported that across the 53 included papers, the percentage of older adults meeting the guidelines varied widely, ranging from 2.4% to 83.0%. Similarly, the high percentage of participants reporting depressive symptoms and the fact that those in the pain groups reported more depressive symptoms than those without pain highlight the importance of considering depression in the primary care. This is in agreement with a previous study of our team6 where depression emerged as the second most important predictor of self-reported disability. Also Penninx et al.,35 found that depression has a large impact on physical decline over time among community-dwelling older persons.

This study has several implications for clinical practice at the primary care setting, in particular for the assessment of patients with pain:

- •

Pain should be routinely assessed at primary care for older adults and patients with a specific pain complaint should always be screened for pain in other body sites as pain at multiple body sites is highly common;

- •

Generic measures of self-reported and performance-based disability, WHODAS 2.0 and SPPB, respectively, are able to capture pain associated disability and therefore could be included in the routine assessment of patients with pain independently of pain location;

- •

Generic measures of physical activity and depression are able to capture differences between patients with and without pain and could also be included in the routine assessment of patients with pain independently of pain location.

Additionally, our results suggest that pain management should consider addressing generalized pain rather than pain at specific locations or at least consider whether managing pain at one body site has beneficial effects on the generalized pain and that pain management strategies should consider depression and physical activity.

Study limitationsThe results of this study need to be seen in light of its limitations. First of all, reason to seek primary care and which painful site was the main complaint were not known. This limits the interpretation of study results, but also suggests that pain is relevant even in situations where it might not be the reason to seek primary care.

Secondly, patients were asked to report on pain intensity considering all pain sites, rather than a specific pain site. This precluded pain intensity comparisons between pain groups. Thirdly, we did not include measures of upper limb performance. Study results show that participants reporting pain in the neck and upper limb had lower scores in the SPPB, which includes tasks that are heavily dependent on lower limbs function. The opposite, i.e., whether groups reporting pain in the lower limbs performed worse in upper limb measures than those without pain could not be assessed. Finally, as patients in one pain group could also belong to other pain groups it was not possible to statistically compare these groups. Future studies should compare patients with different specific body site main complaints.

ConclusionsPrimary care patients present with multiple pain sites which are associated with self-reported and performance based disability, decreased physical activity and increased depression. Generic instruments of self-reported disability (WHODAS 2.0), performance (SPPB), physical activity (RAPA) and depression (GDS) were able to capture changes associated with pain independently of pain location. Therefore, these instruments should be considered in the routine assessment of patients reporting pain at primary care.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank all people from the Agrupamento de Centros de Saúde Baixo Vouga that directly or indirectly contributed to this work and to the students that contributed to data collection.