Although widely analyzed by authors and theoretically valued by the public, the right to health data confidentiality seems to be more of an academic figure than a real protected right. This happens due to intrinsic problems with the practical enforcement of some patient's rights, but is getting more notorious in contemporary society.

This article describes the rights to health data privacy and confidentiality in their classical contours, focusing on areas of consensus and controversy and analyzing the recent transformations in society that are causing a crisis in these same rights. We agree that there are reasons to believe that there are no novel legal instruments in Health Law to redeem these rights, except for European Data Protection Law. Here, we briefly analyze the new European data protection draft regulation, which intends to bring reinforced tools on this domain.

We conclude that the juridical aura that still embraces the right to medical and genetic data confidentiality in Health Law and Bioethics seems to no longer have a practical sense. However, despite this perception, the essential dimension of individual freedom relating to personal information and to the notion that the less is known about us the freer we all are is still very relevant and so Health Law needs to dedicate more attention to the transformations of privacy and confidentiality in the medical and genetic fields in order to maintain them protected and respected.

Apesar de amplamente analisado pelos autores e teoricamente valorizado pelo público, o direito à confidencialidade dos dados de saúde parece ser mais de uma figura académica do que um direito realmente protegido. Tal acontece devido a alguns problemas intrínsecos na aplicação prática de alguns dos direitos dos doentes, mas torna-se cada vez mais notório nas sociedades contemporâneas.

Este artigo descreve, em primeiro lugar, os direitos à vida privada e à confidencialidade de dados de saúde nos seus contornos clássicos, mostrando as áreas de consenso e controvérsias em torno deles. Em segundo lugar, analisam-se as recentes transformações na sociedade que estão a causar uma crise nesses mesmos direitos, sendo esta capaz de os transformar ou mesmo de os eliminar como direitos dos doentes verdadeiramente respeitados. Neste capítulo, constata-se que há fortes sinais para acreditar que no Direito da Saúde e na Bioética os direitos à vida privada e à confidencialidade estão a sofrer uma crise e que não se têm criado quaisquer instrumentos legais inovadores em Direito da Saúde para os resgatar, ao contrário do que acontece no Direito Europeu de Protecção de Dados. Esta premissa leva à terceira parte do artigo, onde se analisam brevemente a proposta do novo regulamento europeu de proteção de dados pessoais, cada vez mais perto de ser publicado, o qual pretende trazer ferramentas reforçadas neste domínio.

Conclui-se que a aura jurídica que ainda envolve os direitos à confidencialidade dos dados médicos e genéticos em Direito da Saúde e Bioética não parece ter já um sentido prático, sendo quase como promover um produto com enorme potencial mas que não existe no mercado. A única área que ainda se move na frente de defesa da vida privada e da confidencialidade de dados pessoais na nossa sociedade é o direito europeu de proteção de dados. No entanto, mesmo que este facto apresente novas tendências legais que podem ajudar a dar aos direitos dos doentes à vida privada e à confidencialidade dos seus dados um pouco mais de força, pensamos que, apesar das medidas europeias inovadoras, o Direito da Saúde precisa de se dedicar mais a produzir um novo pensamento jurídico operacional para que os direitos à vida privada e à confidencialidade nos futuros cenários da Medicina e da Genética continuem a ser respeitados.

“Issues of privacy have become entangled with bioinformatics as, increasingly; we rely on technology rather than on human beings to resolve privacy issues.”1(p6) “New technologies upheave old norms, and new norms need to be negotiated: a process that takes time.”2(p125)

Although we are aware that the topic of this article is not novel, we think that it still needs attention as continuous transformations in society are constantly bringing new facts that reflect upon the rights to privacy and confidentiality as patient's rights either in healthcare or medical research settings.

Baring this premise in mind, this paper aims to discuss the classical concepts of the rights to privacy and confidentiality in health versus the recent development and solidification of a permanent “reality show” society which trivializes the disclosure and the dissemination of personal data, including health data. More and more people adhere to free information and are ignorant or reluctant to data protection principles until they suffer considerable consequences. Nevertheless, litigation regarding the rights to privacy and confidentiality of health data is rare. As some authors put it “the (…) issue of medical confidentiality has been more discussed than litigated.”3

There is an ample Health Law and Bioethics literature on the importance of the right to confidentiality of medical and genetic data, which is considered a fundamental patient right and is enshrined in the Law of several countries. This right is also one of the main data protection rights. Importantly, medical and genetic data are considered exceptionally sensitive data by current Data Protection Laws, which is a special status requiring extra security and confidentiality protection measures. The reason for this special status is that medical and genetic data are considered to belong to the “private” sphere of the person (data subject), as they relate to the most intimate personal areas. Hence, an unauthorized disclosure of this data is potentially meant to cause discrimination and stigmatization in the personal, professional or social life domains of the data subject. Concurrently, health data privacy is also a very important tool in Public Health policies (e.g. for the acceptance and success of name-based surveillance).4

From the Hippocratic Oath, to the right to be forgottenThe duty of confidentiality is a medical deontological pillar since the Hippocratic Oath, dating back to the 5th century BC. On the other hand, the right to privacy is a relatively recent juridical concept. The classical conception of the right to privacy sprouts from the notion that throughout life every person moves within juridical spaces with varying degrees of liberty.5,a Such spaces can be broadly grouped into two main areas, a public and a private sphere. When we move within our public sphere whatever we do, say or choose can be considered public information in a way that no restrictions are placed to its diffusion and dissemination. In parallel, inside our private sphere, special care must be exercised in order to restrict access and sharing of information so that special limits, which are defined by the individual, are not crossed unless a very significant public interest is at stake. The right to privacy is in that sense a “personality right”6,b rooted in the need to respect the autonomy of people and aimed at protecting them from harm.7 The concession to every human being of an individual private space is deeply connected with values such as freedom and self-determination. Certainly, the borders between public and private spheres vary significantly depending on historical and sociological contexts, political conditions and even personal and individual representations of reality. It has been more than 120 years since Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis8 wrote “The Right to Privacy” an influential Harvard Law Review article drawing attention to the need of protection against the invasion of privacy. In this article, the authors defined the concept of privacy protection by adapting a famous expression of judge Thomas Cooley (regarding tort injury) as “(…) an instance of the enforcement of the more general right of the individual to be let alone”.8

The premonitory significance of this article and the increasing difficulty and necessity to find the correct measures to protect privacy in an age of fast-paced technology-driven progress are well acknowledged. In fact, just about one hundred years after Warren and Brandeis, in a persuasive 1998 New Yorker essay titled “Imperial Bedroom”, Jonathan Franzen depicted privacy as “(…) espoused as the most fundamental of rights, marketed as the most desirable of commodities, and pronounced dead twice a week”.5 Interestingly, in “Imperial Bedroom” Franzen also quoted Richard Powers’ definition of the private aspects of the self as “(…) that part of life that goes unregistered”.5

These quotes reflect the present state of the right to privacy, which was born out of a world that had just discovered the wonders and perils of the telephone or photography and today is threatened by our technology-swamped lives. We concede that the challenges that technology poses to the right to privacy and confidentiality are many and that society has evolved in ways that seem to contradict the almost revered importance that these rights once had. However, such challenges do not necessarily correspond to oblivion of these rights. Evidence has shown that regarding health and genetic data, the protection of these rights is still a priority for patients and physicians.7,9,c Furthermore, it is the main concern of the public regarding the donations of their own biological material to biobanks.10 These facts suggests that privacy and confidentiality are still valued concepts by most people and therefore did not lose all their practical sense.

Some of these factors, which explain a diminishing value of the rights to privacy and confidentiality, were generally identified by the European Commission as a basis for the ongoing reform of data protection in the European Union (EU).11 In this article we highlight the efforts on new data protection mechanisms, which have been developed by the European Commission (EC) and coined in the draft of a new data protection regulation,d as a good example of confidentiality rights resilience.11 We analyze this new legal turn in data protection in the EU and make some considerations on its relevance for the confidentiality of personal health data. In brief, the new regulation will give more power to customers of online services, determine stronger safeguards for EU citizens’ data that gets transmitted abroad, and considerably increase fines on companies that breach the law. Importantly, in the regulation draft, health data are still considered “particularly sensitive and vulnerable in relation to fundamental rights or privacy” deserving “specific protection”.11

We also examine the new “right to be forgotten” which is also enacted in the already mentioned regulation draft on data protection and was recognized by the Court of Justice of the European Union on May 2014 in the Google Spain SL, Google Inc. vs Agencia Española de Protección de Datos case.12

In brief, this article aims mainly to summarize the issues and questions raised in the health data protection field, rather than to provide any solutions. Nonetheless, bearing the new European Law developments in mind, this article ends with our last word on the status quo of privacy and confidentiality of personal health data rights.

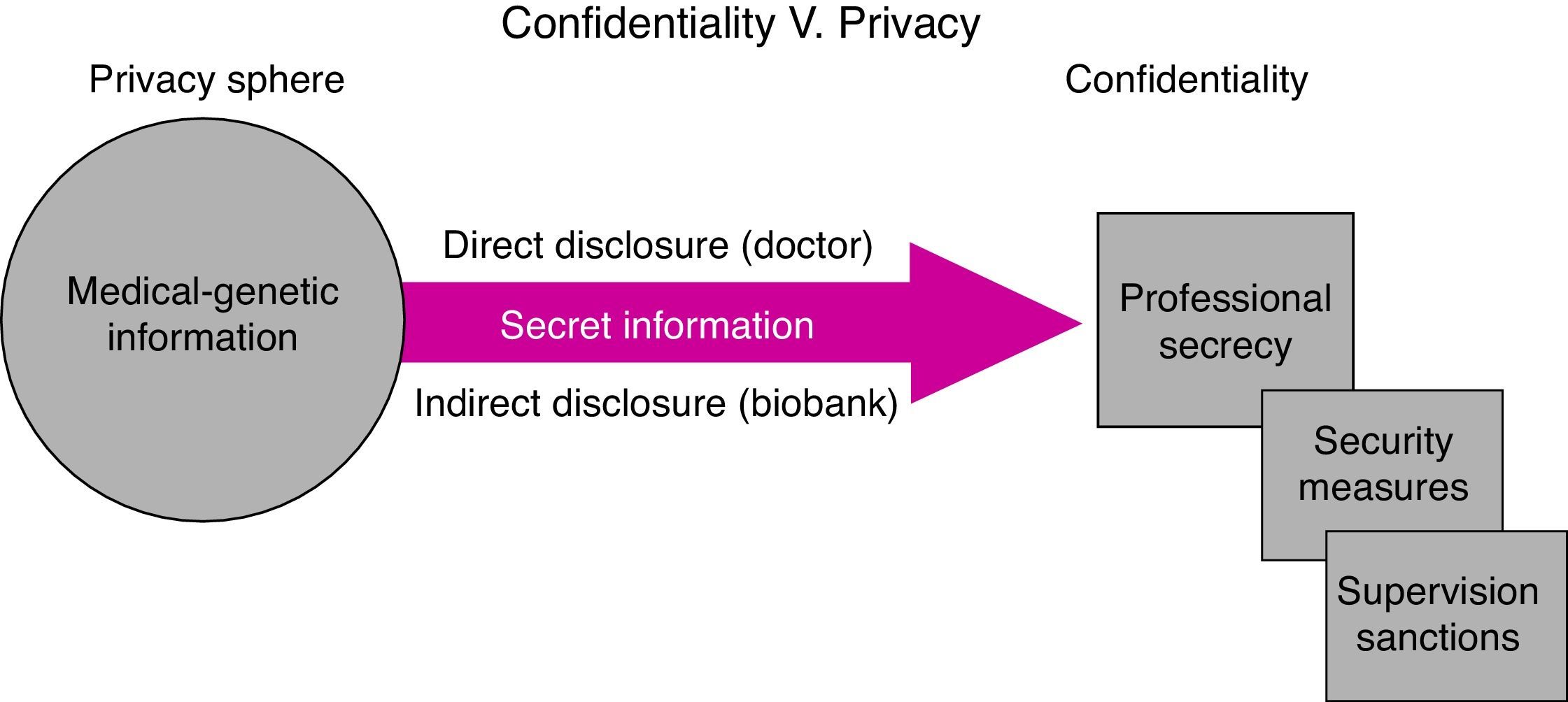

State of the artThe rights to privacy and confidentialityThe right to confidentiality is based on the fundamental rights to privacy and to “informational self-determination”, which relate to personal data protection (data protection rights). However, confidentiality is a different concept than privacy, and it comprises more than data protection rights. Firstly, confidentiality works downstream of privacy and for confidentiality to be legally “triggered”, privacy must have already been disclosed.13 Furthermore, on one hand the right to privacy is what is called a “negative” right because it claims non-interference with information belonging to the private sphere. On the other hand, confidentiality is both a “negative” and a “positive” right as it similarly claims non-interference or silence (e.g. in the form of professional secrecy) but also practical protective actions (e.g. security measures; supervision; sanctions – see Fig. 1).

Historically, understanding the real meaning and the limits of the right to confidentiality can be better achieved by taking a look at the 1988 English tort law case Attorney General v. The Observer Ltd.14 This case covered the publication in several British newspapers of excerpts from the controversial book Spycatcher, written by former MI5 counterintelligence officer Peter Wright. The book, at the time already published in the USA and Australia but not in England, contained details about Wright's activity in MI5, which constituted a violation of an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom – the Official Secrets Act 1991 – protecting state secrets and official information. In his argument in the House of Lords, Lord Goff of Chieveley identified a vital dimension of the right to confidentiality – the duty of confidence. According to Lord Goff of Chieveley, this duty “(…) arises when confidential information comes to the knowledge of a person (the confidant), with the effect that (…) he should be precluded from disclosing the information to others”.14 Therefore, he concludes “(…) there is such a public interest in the maintenance of confidences, that the law will provide remedies for their protection”.11 Importantly, Attorney General v. The Observer Ltd. also permitted to identify the limits to the right to confidentiality. First, the right to confidentiality only applies to confidential information and not to information that has already entered the public domain (information for which there is general access). Second, the right to confidentiality does not apply to trivial information. Third, and perhaps most significantly, the public interest of confidence protection must be balanced in the face of other public interests. In this regard, Lord Goff of Chieveley declared that “(…) it is this limiting principle which may require a court to carry out a balancing operation, weighing the public interest in maintaining confidence against a countervailing public interest favoring disclosure”.14

As Attorney General v. The Observer Ltd. so well illustrates, the most controversial part of the right/duty of confidentiality is the zone where this right has to be balanced with other conflicting public interests. In fact, this zone of conflict has been the subject of intense study in the fields of Health Law and Ethics mainly in the domain of HIV infection (probably the most controversial) and, particularly, in the related tension between the duty of professional/medical secrecy and the duty to disclose personal health information for the purposes of protecting a third party's health or life. Importantly, recent advances in genomics and the possibility to define someone's future risk of developing a disease by analyzing hereditary genetic information feeds into the same discussion and illustrates that this debate is very much alive in our time.15

Understanding the tension between the right to/duty of confidentiality and public interest must also be informed by a closer look at different definitions of the latter. Public interest is an open and ever evolving concept. Many would argue that no matter the extent to which the concept evolves and transforms, public interest should never be allowed to be confused with curiosity or voyeurism and that exaggerated broadening of some definitions of public interest would, ultimately, end up emptying the notion of private information, turning it into trivia, and defeating the purpose of recognizing a right to confidentiality with balanced limits. On the other hand, others argue that we are moving towards a broad notion of public interest that would, most of the times, favor disclosure of information. According to this notion the alternative public interest related to protecting confidence looks increasingly more like a private interest. No matter which side we take on this argument, it is important to balance public interest with confidentiality and identify and discuss relevant factors leading to a possible fading or transmutation of the latter.

The rights to privacy and confidentiality are nowadays entangled with the right to the protection of personal data, which is established by Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU,16 Article 16 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU),17 and in Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).18 As underlined in 2010 by the Court of Justice of the EU in the joined cases Volker und Markus Schecke GbR and Hartmut Eifert v Land Hessen,19 the right to the protection of personal data is not an absolute right, but must be considered in relation to its function in society. Data protection is closely linked to the respect for private and family life protected by Article 7 of the Charter.16 This is reflected by Article 1(1) of Directive 95/46/EC20 which provides that Member States shall protect fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons and in particular their right to privacy with respect to the processing of personal data.

Whatever happens in the data protection law field will affect tremendously the rights to privacy and confidentiality in the health law domain. This is why the ongoing reform in European data protection legal instruments is so important to discuss here. In a 2012 document preceding the draft of the new EU regulation, with the suggestive title of Safeguarding Privacy in a Connected World – A European Data Protection Framework for the 21st Century,21 the European Commission undoubtedly shows that the protection of privacy and confidentiality rights is the core of data protection law. This document identifies as the major challenge for today's data protection, the new ways of sharing information, through social networks and remote storage of large amounts of data, which “have become part of life for many of Europe's 250 million internet users”.21 Nevertheless, it stresses very clearly that “in this new digital environment, individuals have the right to enjoy effective control over their personal information”.21

In a way, we think that, at present, data protection law is the “practical” or “feasible” part of the defense of the rights to privacy and confidentiality of health information. This is particularly so as nowadays, the compliance with these rights essentially depends almost totally on the existence of very objective security measures in healthcare information technologies (IT). For instance, the concept of “privacy by design” brought up by the EU data protection reform and also included in the draft of the new regulation,11,e if adopted in healthcare units could be the key to prevent breaches of confidentiality “from scratch”. However, the costs and technical implications of these measures may be dissuasive, particularly if sanctions for not complying with data protection measures are not strong enough or if control by the competent authorities is inexistent.

Nowadays, personal health data are stored and accessed in different systems, sometimes independently of secrecy duties. In other cases, such data can even be stored in the Cloud, although this practice is considered to be inadvisable by data protection commissioners. Hence, it is obvious that in order to protect the right to confidentiality in contemporary societies and healthcare units, information technology systems must provide the appropriate mechanisms to avoid illegitimate breaches of patient's data. A very important corollary of this is that confidentiality became expensive to protect and, as such, it may come to be more of a “luxury” to health management than a basic necessity. This tendency may even be more acute for the health care systems in an inverted demographic pyramid world.

Consensual and defying ideasThe interconnected rights to privacy and confidentiality regarding medical and genetic information have been amply discussed in the Bioethics and Health Law fields and have been the object of consensual and defying ideas. In the first group, it is indisputable that as a centenary medical duty, the duty of medical secrecy is still key to the medical business. Without the perception that physicians are bound by a duty of medical secrecy, certainly most patients would not disclose some of their intimate clinical history. Furthermore, it is important to highlight the consensual notion that the right to confidentiality in health works not only to preserve a significant element of trust, which is of vital importance in most interactions in the healthcare context, but also to prevent stigmatization and defend against discrimination. Therefore, confidentiality protection measures are valuable public health allies, not only in the history of epidemics as already mentioned above4 but also in relatively new areas, such as public health genomics (e.g. without trust in the confidentiality of biobanks for research purposes, people are not willing to donate their DNA10).

However, relevant as they may be, the traditional concepts of privacy and confidentiality have been significantly defied. The first noteworthy example is that of the famous 1982 New England Journal of Medicine article by Mark Siegler,22 which denounced the excessive number of people accessing medical records in hospitals, leading to the characterization of confidentiality in medicine as a “decrepit concept”.22 Twenty years after, an extensive literature review by Pamela Sankar and colleagues illustrated a general unawareness or misunderstanding of the ethical and legal right to medical confidentiality by patients, which prompted the authors to label the concept as both “over and underestimated”.23 Notably, widespread confusion (and in some cases ignorance) about confidentiality and its relevance in the biomedical arena is thought to be influenced by the inexistence of a clear, precise and harmonized definition of what constitutes “confidential data”. This imprecision has led some authors to portray confidentiality as a “Tour of Babel”.24

In addition to the aforementioned issues on a lack of clear definitions of “confidential data” and privacy boundaries, recent trends in the context of genetics (for example in the context of biobanking) provide novel challenges to health privacy. The advancement of technology and its impact in molecular biology research also brought agitation and stress to the concepts of privacy and confidentiality. In summary, can these concepts survive in the form of a duty of genetic confidentiality and genetic privacy rights? Let us look at the example of biobanking. In biobanks there is no “privileged” relationship3 between the scientists on one side and the research participants on the other, contrarily to what happens in the patient-physician biomedical relationship. This contrast necessarily begs the need of a redefinition of the legal basis in which personal information is shared and protected in biobanks. In face of these new challenges, the necessary departure from classical notions is sometimes so significant that some authors consider that concepts cannot bend that far without being irreparably broken and therefore wonder whether confidentiality is now but an obsolete concept.25

To close this brief presentation of defying ideas on health and genetic data privacy and confidentiality we should mention the issue of anonymization of human biological materials (HBMs). In reality, biobanking activities pose privacy and confidentiality obstacles that at first glance seem to be surpassed if the concept of confidentiality is redefined and reconfigured, moving on from a trust-based model of information secrecy, towards an anonymized-data model.26 The pre-requisite would be that anonymization would become a core requirement to build a biobank. However, anonymization of HBMs poses several questions, which endanger this apparent solution. Quoting Mariachiara Tallacchini”27 the rationale behind this model is based on the assumption that the de-identification of the human biological materials (HBMs) cancel their “subjective traceability”, i.e. the characteristics that render them re-identifiable, and that this is “the technical filter which guarantees data confidentiality” (by using different methods of encrypting the sensitive information).27 Nonetheless, the same author interestingly suggests that there are areas of doubt in the validity of this “guarantee”. Firstly, by stating that “the expression ‘anonymization of data’ often conceals situations in which, in fact, the possibility of reidentifying data still exists, and, therefore, in which anonymity is neither real nor complete” (…). Secondly, and perhaps more critically, by considering anonymity as “the rhetorical strategy for denying the existence of any subjective interest in HBMs and, consequently, for affirming their free availability to those who may make interesting use of them: the biotech industry”.27

In summary, the aforementioned consensual and defying ideas clearly illustrate how the field of health and genetic data privacy and confidentiality rights is a very complex legal ground, which claims for more dedicated attention from academics in the field of Health Law.

Factors that are transforming health data privacy and confidentialityThe progressive erosion of our own private spheres2 is now contributing to the growth and expansion of a global public sphere we all share. Privacy concessions can be observed everywhere and have multiple causes and aims. Security, for example, is the prominent cause for disclosure of private data. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States of America, privacy concessions based on security reasons were greatly expanded.28 Concomitantly, intrusions in our private spheres such as airport screening, collection of fingerprints and photographs and extensive video surveillance are now widely accepted and perceived as normal practice. Remarkably, people are not only tolerating privacy concessions for shared purposes such as common security but also increasingly opting to give away privacy for individual gains, such as fame, money and recognition. TV shows and social phenomena where people linger on other's most intimate moments such as precise first-hand accounts of deeply traumatic experiences (including health-related conditions) have gained significant notoriety. The case of Jade Goody, a 27 year-old British Big Brother participant is an extreme example of exposure of terminal illness in the media. Goody raised around £1m from media deals signed since she was told she had terminal cervical cancer. Her main reason to sign these contracts for a live coverage of her final days was to leave the money to her children.f

In Portugal, very recently, Manuel Forjaz, a well-known and charismatic academic famously shared writings and photos on social media about the progression of his cancer, including chemotherapy sessions, its secondary effects and consequent suffering. During this period he participated in a weekly TV show and spoke regularly and openly in public about his disease. He died a few days after publishing a book about his shared experience as a cancer patient.29 These situations illustrate the possible transformation of the nature of health data from a paradigm of secrecy made of a certain “embarrassment”,3 into a possible future paradigm of openness. Overall, health data are becoming socially acceptable information and its self-disclosure is becoming trivial. However, this tendency certainly does not suit everyone as different people have very different notions of what they want to keep private. Still, the paradigm may be changing, and it would be at least doubtful if someone who shared his or her health condition on social media could subsequently try to sue those who decided to share that information outside the circle within which that information was originally shared. Hence, in a world where health information too becomes widely shared on social networks, society can relativize the rights to medical and genetic privacy and confidentiality, which may ultimately pervade law and justice.

Trivialization of the sharing of formerly considered “sensitive data” is also becoming more acute due to the almost impossible task that is required of data protection authorities to control the multitude of health data, which is currently being collected. On the other hand, building systems that secure confidentiality is sometimes considered a luxury, which is neglected by health administrators, particularly in countries where financial crises have led to austerity measures (e.g. Portugal). In the case of Portugal, the absence of systematic supervision and sanctions by data protection authorities, which struggle with lack of means, together with the almost inexistent litigation in this domain, result in random privacy or confidentiality protection concerns in healthcare units. As a consequence, anecdotal evidence indicates that it is possible for administrative staff to access patients’ medical histories, in violation of national law. Unsurprisingly, in countries where social welfare is jeopardized, patients prioritize access to care over any other rights and are less prone to complain of cases involving a violation of privacy and confidentiality rights.

Genetic privacy and confidentialityNotably, this erosion of health data privacy and confidentiality finds parallel in more specific phenomena in the areas of genetics and genomics. Here again, privacy concessions are motivated by public and private interest alike. As we know, the Human Genome Project (HGP) and the advent of genomics have highlighted (or at least promised) the importance of genetic data in fighting disease and improving health outcomes. For example, different Public Health fields, such as infectious and chronic disease, occupational health and environmental health can advantage from the progress of genomics and the sharing of genetic data, leading to what has been described by some authors as “Genetic information for all” syndrome.30 This subject and the related issue of personalized medicine (where therapy is specifically designed to an individual based on his/hers genetic profile) have deep privacy and confidentiality implications. First and foremost, we must consider whether our genetic information can contribute to significant conclusions about our risks of developing future diseases. If that is established, at least at a reasonable level, genetic data need to be considered as private as any other health data. Nevertheless, it is clear that if someone carries a genetic alteration that has been associated with a significant and elevated risk of developing a disease in the future, that information could be useful to family members who might share that same alteration. Despite the fact that different studies show that the overwhelming majority of patients choose to pass information of genetic risk and genetic disease to family members, in some cases sharing information collides both with the patients’ will and the right of family members not to know.31,32 Hence, in pondering whether or not to share genetic data with family members, the probability that the disease will develop and the magnitude of the harm should that disease indeed develop must be balanced and weighted against the costs (individual and public) of breaching confidentiality duties.13 Hence, clearly, the advances in genetics and genomics pose significant challenges to privacy and confidentiality too.

Finally, a supplementary note to mention that, in line with the aforementioned security concerns and therefore perhaps unsurprisingly, in some cases it is already accepted to give away genetic privacy for justice reasons. For example, the UK National DNA database already includes DNA profiles of more than 3 million individuals, covering more than 6% of the population and raising privacy and confidentiality issues amongst other innumerous bioethics and human rights questions.33–35 The topic of genetic privacy and biobanks for forensic purposes, however, will not be debated here as it goes beyond the scope of this article.

The European Data Protection Law reform: the redemption of health data privacy and confidentiality rights?Preliminary noteIn the previous sections we identified reasons to believe that the rights to health data privacy and confidentiality – once so cherished in Health Law – are suffering a crisis. This crisis is caused not only by general societal phenomena but also by specific factors related to the fields of healthcare and genomics. We also mentioned that we consider data protection law as the “practical” or “feasible” part of the defense of the rights to privacy and confidentiality of health information as, currently, the compliance with these rights essentially depends on security measures and information technology (IT). Hence, we agree that whatever happens in the data protection law field will have a significant impact in the rights to privacy and confidentiality in the health law domain. Considering that European Data Protection Law has been recently subject to a considerable reform, including a new European regulation draft, it is very important to analyze it here, although not in detail, as this does not fit exactly the scope of this article, which is oriented to Health Law and Bioethics and not to Data Protection Law issues, which other authors have discussed elsewhere.36,37

The EU reform of the data protection legal framework“Rapid technological developments have brought new challenges for the protection of personal data. The scale of data sharing and collecting has increased dramatically. Technology allows both private companies and public authorities to make use of personal data on an unprecedented scale in order to pursue their activities. Individuals increasingly make personal information available publicly and globally. Technology has transformed both the economy and social life.”11(p1)

In 2012, the European Commission (EC) proposed a key reform of the EU legal framework, which led to the draft of a new European regulation on the protection of personal data. This regulation intends to strengthen individual rights and tackle the challenges of globalization and new technologies (mainly on-line) by adapting the general principles which were considered to remain valid to these challenges while maintaining the technological neutrality of the legal framework.

When it comes into force, which has become more likely to happen after the majority of the European Parliament approved its draft (March 2014), the new Regulation (henceforward cited as “the Regulation”) will immediately become the new general legal framework of data protection in all member States of the EU, abolishing the long time ruling of Directive 95/46/CE.20 The pathway to this reform was based in several documents from different entities, some of which included innovative mechanisms to protect personal data against the challenges it endures at present time.38 This pathway also included a Eurobarometer 2011 survey39 on the attitudes towards data protection, which showed interesting results and revealed that the majority of Europeans feel obliged or are willing to give up their privacy and confidentiality almost on a daily basis. Results of the Eurobarometer 2011 survey showed that 58% of Europeans feel that there is no alternative other than to disclose personal information if they want to obtain products or services; 79% of social networking and sharing site users were likely to disclose their name; 51% their photo and 47% their nationality. Online shoppers typically gave their names (90%), home addresses (89%), and mobile phone numbers (46%). Only a third of Europeans were aware of a national public authority responsible for protecting their personal data rights (33%) and just over a quarter of social network users (26%) and even fewer online shoppers (18%) felt in complete control of their data.39 Importantly, these numbers just confirmed what the European institutions already suspected. In 2010, in a Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, titled “A comprehensive approach on personal data protection in the European Union”,40 the Commission concluded that the EU needed “a more comprehensive and coherent policy on the fundamental right to personal data protection”.40

The new general rules in the Regulation that can have impact in the protection of health dataThe new EU strategy intends to “put individuals in control of their own data”11 and a new approach to what is considered “nominative data” is adopted in the Regulation. For instance, the acts of being observed and being traced become privacy threats, even without knowing the name of the observed or traced person.36 Article 4/2 of the Regulation determines that personal data “means any information relating to a data subject”. Data subject is defined as “an identified natural person or a natural person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, by means reasonably likely to be used by the controller or by any other natural or legal person, in particular by reference to an identification number, location data, online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that person” (Article 2/1).

A significant improvement is the principle of transparency introduced by Article 5 (Principles relating to personal data processing), which stipulates that personal data must be “processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to the data subject” (Article 5/a).

Two other innovations in terms of data control rights are the right to portability and the right to be forgotten. Article 18/1 of the Regulation determines that data subjects have the right to obtain a copy of their personal data from the controller, in a “structured and commonly used format which is commonly used and allows for further use by the data subject”. In Article 18/2 it is granted to the data subject the “right to transmit personal data and any other information provided by the data subject and retained by an automated processing system, into another one, in an electronic format which is commonly used, without hindrance from the controller from whom the personal data are withdrawn”. As some authors put it, data portability is therefore the right to “take personal data and leave”.36 Importantly, the “right to be forgotten” (and to erasure) is also a new option in the Regulation and has recently been confirmed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (Article 17)12: “Any person should have the right to have personal data concerning them rectified and a ‘right to be forgotten’ where the retention of such data is not in compliance with this Regulation. In particular, data subjects should have the right that their personal data are erased and no longer processed, where the data are no longer necessary in relation to the purposes for which the data are collected or otherwise processed, where data subjects have withdrawn their consent for processing or where they object to the processing of personal data concerning them or where the processing of their personal data otherwise does not comply with this Regulation. This right is particularly relevant, when the data subject has given their consent as a child, when not being fully aware of the risks involved by the processing, and later wants to remove such personal data especially on the Internet. However, the further retention of the data should be allowed where it is necessary for historical, statistical and scientific research purposes, for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, for exercising the right of freedom of expression, when required by law or where there is a reason to restrict the processing of the data instead of erasing them.”11

In this respect, we agree with Costa and Poullet36 when these authors affirm that the effectiveness of the right to be forgotten relies on a techno-legal approach, as technical solutions have to be adopted to ensure the erasure and blocking of data on the Internet. This fact is related to another innovative rule of the Regulation, the introduction of a “privacy-by-design” obligation.

“Privacy-by-design” is established in Article 23 of the Regulation (Data protection by design and by default) giving data controllers the duty to “Having regard to the state of the art and the cost of implementation (…) both at the time of the determination of the means for processing and at the time of the processing itself, implement appropriate technical and organizational measures and procedures in such a way that the processing will meet the requirements of this Regulation and ensure the protection of the rights of the data subject” (Article 23/1). The European Commission is the institution empowered to specify data protection by design requirements “applicable across sectors, products and services” (Article 23/3).

Very important to the future of personal data protection in general and in the field of health and genetic data privacy and confidentiality rights, in particular, is the new approach found in the Regulation in what refers to Responsibility and Liability. Differently from the Directive 95/46/CE, the Regulation is very much concerned about responsibility, and clearly states that the controllers of data are responsible to implement data security requirements (Article 23). Importantly, the Regulation determines a “principle of accountability” and describes in detail the obligation of the controller to comply with the Regulation and to demonstrate this compliance, including by way of adoption of internal policies and mechanisms for ensuring such compliance.11 This is a very important step ahead in the general protection of personal data, which can have a huge impact on health data controllers and processors (Article 22 on the responsibility of the controller). Furthermore, in terms of liability, the Regulation presents two considerable modifications to the Directive. It makes processors (those who process data on behalf of controllers) liable for damages and when these are multiple it establishes a “joint liability” avoiding the necessity to identify the one at fault (Articles 23 and 24). The Regulation also imposes on controllers and processors the duty to cooperate with the supervisory authority (Article 29).

In brief, with all these new data protection enforcement mechanisms the Regulation seems to bring the possibility of a new era for privacy and confidentiality rights and implicitly to health and genetic data protection. Nevertheless, in specific terms the only innovation in the Regulation which targets health data is Article 84, inserted in Chapter IX (Provisions relating to specific data processing) on “Obligations of secrecy”. In this disposition it is stated that within the limits of the Regulation, Member States may adopt specific rules (which have to be notified to the European Commission) to set out the investigative powers by the supervisory authorities “in relation to controllers or processors that are subjects under national law or rules established by national competent bodies to an obligation of professional secrecy or other equivalent obligations of secrecy, where this is necessary and proportionate to reconcile the right of the protection of personal data with the obligation of secrecy”.41,g For the remaining, the Regulation maintains the concept that “health related data” and “genetic data” must be considered as “sensitive data”, and as such require more data protection safeguards. Article 9 of the Regulation11 sets out the general prohibition for processing special categories of personal data, including “data concerning health” and the exceptions from this general rule, building on Article 8 of the Directive 95/46/EC.20 Strangely, article 81 of the Regulation which defines the processing of health data does not include genetic data. The Regulation defines both “genetic data” and “data concerning health” (Article 4) but it is obvious that this sector was not a major concern in the EU data protection reform.

Overall, some of the new instruments proposed for a renewed framework for data protection in Europe can give a practical sense to the rights of privacy and confidentiality in healthcare and genetic settings, transforming them from rhetorical figures into real obligations to the counterparts (health and genetic data controllers and processors). For instance, the obligation to build “privacy by design” for the processing of health data or biobanks will be key for health information systems’ managers. For example, in Portugal, a comprehensive and official Health Data Platform42 has been launched without truly informing the public about health privacy and confidentiality issues. Furthermore, there is no mention in the Platform website to the rights of the people who will be putting there their medical data lacuna, which would have been impossible years ago. Moreover, the National Data Protection Commission is not referenced in the portal as having given its authorization to treatment of medical data at such an extension. We think that when in force, the new rules from the EU Regulation will have a positive impact on the privacy and confidentiality of patients’ data, which urgently need redemption in Portugal.

Last word“But someone will always have to speak for privacy, because it doesn’t naturally rise to the top of most consideration sets, whether in government or in the private sector.”2(p126)

“You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.” This famous 1999 quote in Wiredh by Scott McNealy,27 was more than an epiphany as it becomes more and more accurate as time goes by.

Certainly, today privacy is a defied and perhaps even compressed concept. Nonetheless, even those willingly sharing their areas of reclusion take offense when seeing others intruding those same areas without their consent. Furthermore, experiencing pernicious effects related to privacy exposure can constitute disturbing incidents, which rarely lead to decisions of maintaining minute areas of personal retreat. Therefore, despite its transmutations and metamorphosis, privacy is still part of our hardwiring as agents endowed with free will. Hence, transformed, nuanced and self-affirmed concepts of privacy still persevere in these highly demanding circumstances.

In a way, the facts are not suiting any data protection rights, but the new EU regulation seems to want to protect these rights against all odds, reinventing data protection in a mix of a legal-technological approach. Nevertheless, we must not be naïve, and it is important to notice that the ratio of the EU concerns is not linked to a human rights based philosophy or defense, but mainly to economic motives. The fundamental goal of the new EU instruments on data protection is the “building of trust in the online environment” which is “key to economic development as lack of trust makes consumers hesitate to buy online and adopt new services”.11 Novel policies on data protection in Europe aim to avoid the risks that fear of an uncontrolled sharing of data may slow down the development of innovative uses of new technologies. It is mentioned in the explanatory memorandum of the Regulation11 that “heavy criticism has been expressed regarding the current fragmentation of personal data protection in the Union, in particular by economic stakeholders who asked for increased legal certainty and harmonization of the rules on the protection of personal data”. Also, the complexity of the rules on international transfers of personal data is considered as constituting a “substantial impediment to their operations as they regularly need to transfer personal data from the EU to other parts of the world”.11 Nevertheless, even when economic motivations are driving reform, fundamental human rights to privacy and data protection and confidentiality may benefit from the new EU Regulation.

In reality, even if the erosion of the rights to privacy and confidentiality in the health care and biobanking fields becomes clearer, the public and health professionals still demand at least a perception of the observation of these rights. The facts though seem to reveal an unstoppable fading of the frontiers of private life, especially in the healthcare domain. Clearly, many changes occurred during the 100 years that mediated between “The Right to Privacy” and “Imperial Bedroom”. The birth of the portable snapshot photography camera and later of the video camcorder, the mobile phone industry, the mass use of computers and the dawn of the internet are good examples of technology-propelled social transformations that provide a challenge to classical constructions of individual rights and freedoms. However, despite all these transformations the essential dimension of individual freedom relating to personal information and to the notion that the less is known about us the freer we all are is still very relevant and well grounded. In terms of our individual selves, fears of invasion of our most private lives remain justified and perhaps even further, as more and more information is known and shared about us, using a multitude of different communication channels. As far as our collective selves go, our social tolerance towards information dissemination and data sharing is also increasing in tandem with the expansion of phenomena such as social media and online social networks. Therefore, individuals and society in general seem now more willing to accept a level of information disclosure far higher than before. As more and more is known and shared about us the more we tend to cherish whatever part of us is left uninvaded. Not surprisingly, fourteen years on since Jonathan Franzen's New Yorker essay, discussion around the issues of privacy protection and confidentiality breaching are undoubtedly as prominent as ever. This urge comes perhaps from the utilitarianism of our times, which overthrows the worries of public authorities and private corporations with individual privacy and confidentiality and data protection rights in healthcare and genetics. Because economics is getting the last word, expensive rights can soon vanish from the Law.

Consequently, we think the rights to privacy and confidentiality have to be reframed in the context of Health Law and Bioethics and be seen more as data protection rights and less as mere reflections of the Hippocratic Oath. Silence is no longer enough to protect our personal health information. On the contrary, information technologies built to protect medical and genetic privacy can perform this role, but Law has to provide obligations and sanctions to make these enforceable. As long as top administrators and IT professionals working in healthcare units and biobanks are not heavily sanctioned for lack of compliance with data protection legal requirements the rights to privacy and confidentiality in these settings will still be menaced.

We are watching, at least in Europe, an unacceptable regression of particularly important individual rights. For this reason, as health legal and ethical experts we express the urgent need to update the discussion on the rights to health data privacy and confidentiality and to make sure we will keep these issues alive in contemporary Health Law.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Jonathan Franzen refers to this matter in page 43 of his very acute essay on privacy, called “Imperial Bedroom”: “What really undergirds privacy is the classical liberal conception of personal autonomy or liberty. In the last few decades, many judges and scholars have chosen to speak of a “zone of privacy” rather than a “zone of liberty”, but this is a shift in emphasis, not in substance: not the making of a new doctrine but the repackaging of an old one”.

This is the category of rights in which the Portuguese Constitution includes the right to privacy (article 26). See for all Moreira and Canotilho, Constituição da República Portuguesa, articles 1° to 107°.

Despite the reduced number of court actions against professionals who did not disclose genetic risk to relatives of their patients there is reluctance from physicians and genetic counselors to breach confidentiality.

Regulations are the strongest European Union normative instruments entering in force in all member States as soon as they are published in the Official Journal of the Communities. They differ from “directives”, which need to be transposed to the member States internal legal order.

See section 2 on Data Security, article 30/3 (security of processing) of the regulation draft.

See newspaper articles “Jade Goody to wed and die ‘in the public eye’ The reality TV star will sell media rights to raise money for her children” (The Observer, Sunday 15 February 2009) Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2009/feb/15/jade-goody-cancer) and “Jade Goody set to make £1m from media deals” (theguardian.com, Wednesday 18 February 2009 12.33, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/media/2009/feb/18/jade-goody-wedding-deals).

This importance given to secrecy was also stressed on the Madrid Resolution, signed by the Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners in 2009 where on topic 13 data relating to health or sex life is considered “sensitive data”. In the same document, topic 21 refers to a “duty of confidentiality” which states that “The responsible person and those involved at any stage of the processing shall maintain the confidentiality of personal data. This obligation shall remain even after the ending of the relationship with the data subject or, when appropriate, with the responsible person.”

Wired is a famed magazine on scientific innovations and their impact in society, also known for featuring editorials from industry leaders.