To examine the association between self-reported physical activity and self-reported screen based time.

Materials and methods969 high school students filled in a questionnaire on physical activity and screen based activities. Correlation analysis between time spent in moderate/vigorous physical activities and time spent in screen based activities were performed.

ResultsNo association was found between physical activity and time spent watching TV, playing or using computers. A low correlation was found between time using mobile phones and time spent performing moderate physical activities (r=0.09, p<0.05), and vigorous physical activities (r=0.13, p<0.05).

ConclusionsThese findings suggest that screen time is not displacing physical activity.

Explorar a associação entre o nível de atividade física e o uso de dispositivos eletrónicos.

Materiais e métodosNovecentos e sessenta e nove alunos do secundário preencheram um questionário sobre atividade física e uso de dispositivos eletrónicos. Foi realizada uma análise de correlação entre o tempo despendido em atividade física moderada e intensa e o uso de dispositivos eletrónicos.

ResultadosNão há correlação entre a atividade física e ver televisão, jogar ou usar computadores. Há uma correlação baixa entre o uso de telemóveis e a atividade física moderada (r=0,09, p<0,05) e vigorosa (r=0,13, p<0,05).

ConclusõesEstes resultados sugerem que o uso de dispositivos eletrónicos não interfere com a prática da atividade física.

The evidence of the benefits of physical activity in maintaining good health and function is unquestionable. For children and adolescents in particular, physical activity has been shown to be associated with positive changes in adiposity, skeletal health, psychological health, improved self-esteem, fewer depressive symptoms1 and improved cardiorespiratory fitness.2 Furthermore, it appears to have long term influence on preventing weight gain, obesity, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer's disease and dementia.3 Despite the consensual benefits of physical activity across the lifespan, studies have shown a decline in physical activity and an increase in sedentary behaviors during adolescence.3,4 Increased sedentary behaviors in adolescence have been associated with time spent using electronic devices such as mobile phones, computers, television (i.e., screen time), which in turn, has been shown to be related with hyperactivity/inattention problems, less psychological well-being, less perceived quality of life,5 obesity6 and increased pain prevalence.7

The hypothesis that screen time could displace physical activity has been proposed.8 However, the evidence on the association between increased screen time and decreased physical activity is conflicting. A few studies have found an inverse association between physical activity and screen time,9–11 while others have found no association between these factors.12,13 A recent systematic review identified a negative association between screen time and physical activity/fitness,11 while a longitudinal study found an inverse but non-substantive association between TV/DVD use and leisure physical activity and no association between computer/game use and leisure physical activity,14 suggesting that the association might depend on the type of screen based activity. Furthermore, a cross country study9 suggests that the strength of the association between screen based activities and physical activity depends on gender, country/region, type of screen-based activity and intensity of physical activity. For example, watching television, gaming and using a computer showed different patterns of association with physical activity and the strength of association depended on whether vigorous physical activity or moderate to vigorous physical activity was considered in the analysis. In addition, the strength and direction of the association varied between the South European countries and the Nordic European countries.9 Therefore, more research is needed in Portugal investigating the potential association between screen time and physical activity for students, in particular whether an association between these variables might depend on the intensity and type of physical activity or type of screen based activity. The main aim of this study is to investigate whether an association exists between self-reported physical activity and self-reported screen based time when considering the intensity (moderate or vigorous) and type (e.g. football, skating, cycling) of the physical activity and the type of screen based activity (watching TV/DVD, playing, using mobile phones and computers) in a sample of Portuguese students from the 7th to the 12th grades. Secondary aims are to characterize the type of physical activities and screen based activities in which students are involved and time per week spent performing them.

MethodsThis study received Ethical approval from the Council of Ethics and Deontology, University of Aveiro. Written consent was obtained from the students or from both the students and their parents if students were younger than 16 years old.

Study design and populationThis study took place in the Council of Ílhavo. This Council spent approximately 1.002.6 euros in the year of 2012 in games and sports, an investment that is higher than the National average (data retrieved from http://www.pordata.pt/ on the 30th of May 2016) and its offer in terms of sports/physical activity includes: swimming, athletics, handball, basket, football, martial arts, ballet, tennis, sailing, surf and canoeing. This Council has 5 schools with the 7th or higher grades. These 5 schools had approximately 1330 students from the 7th to the 12th grade at the time of data collection. All these students were invited to participate in the study. A questionnaire was administered using an Electronic Data Capture (uEDC™) Solution developed for this study. This uEDC™ solution (uedc.iuz.pt) is an Electronic Data Capture solution for the healthcare field, using an information system to collect and process clinical data, involving patients, researchers and healthcare professionals. It enables the setup of a clinical study, in accordance with an established protocol defined by the study promotor. During a physical education lesson each student was given an individual password and login and asked to complete the online questionnaire. Students not at school on the day of data collection were invited to participate on another day. Data were collected between March and June 2014.

MeasuresDemographic dataStudents were asked to enter data on sex, age and school year.

Physical activityStudents were asked whether: (1) they participated regularly in the physical education classes; (2) they participated in moderate physical activities other than the physical education classes; and whether (3) they participated in vigorous physical activities other than the physical education classes. Those reporting to participate in moderate or vigorous physical activity had to answer three additional questions related to: type of activity, number of days per week (1–7) and mean duration of each activity per session (minimum 10min). These questions were adapted from Lang.15 Response options for the moderate physical activities question were: walking to school, walking in general (other than to school), cycling, skating, roller skating, others. Response options for the vigorous physical activities question were: handball, running, martial arts, basket, ballet, football, gymnastics, rowing, swimming, volleyball or other. These lists of activities were based in published guidelines.16–18 Moderate and vigorous physical activities were described in terms of number of activities, type of activities and mean duration of activities per week. Total time of moderate and vigorous physical activity per week was computed multiplying the daily amount of time spent in each activity by its weekly frequency (i.e. number of days per week) and then adding the individual time per week for all activities reported by the same participant. Total time of moderate and vigorous physical activity was used to calculate the number and percentage of participants reporting at least 420min of activity per week as recommend in international guidelines of physical activity for health of those aged 5–17 years old (at least 60min of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily).19

Screen based activitiesScreen based activities were assessed with 4 closed questions adapted from Hakala et al.,20 Students were asked to report on the number of hours that they typically spent each day:

- (1)

Watching TV/DVDs: using TVs and DVDs to watch TV programs and videos;

- (2)

Playing: using computers, TV or PlayStation to play wired or standalone games;

- (3)

Using mobile phones: using mobile phones to communicate or play;

- (4)

Using computers: using desktop or portable computers and tablets for communicating and managing information.

Response options for each question were: (1) do not use; (2) use 1h or less per day; (3) use 2–3h per day; (4) use 4–5h per day; and (5) more than 5h per day. Hakala et al.,20 assessed test-retest reliability of these questions using a K coefficient and reported K values between 0.45 and 0.65 indicating a fair to good agreement beyond chance.

Data analysisThe Predictive Analytics Software version 22 (PAWS software) (IBM, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample in terms of age, sex, years of formal education, physical activity and screen time. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported for continuous variables and count and proportion were reported for categorical variables. A Chi-square test was used to investigate differences in the distribution of boys and girls for (i) attendance of physical activity classes, (ii) compliance with international guidelines for physical activity, (iii) type and intensity of physical activity and (iv) time spent (ordinal variable) in each of the four screen based activities. Differences between boys and girls for number of physical activities and time spent in moderate and vigorous activities were investigated using an independent sample t-test. The correlation between time per week spent in physical activity and screen time was investigated using the Spearman rho correlation coefficient and the strength of the correlation was interpreted as low if the coefficient was <0.3, moderate if it was between 0.3 and 0.5, and strong if it was >0.5.21 Level of significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 969 (72.9%) students out of the total number of students (n=1330) answered the online questionnaire. Of these, 502 (51.8%) were girls and 467 (48.2%) were boys ranging in age from 13 to 21 years old (mean±SD=15.6±1.8 years).

Physical activityOf the 969 respondents, 939 (97.0%) reported to regularly participate in the physical education classes against 29 (3.0%) who reported not to participate in these classes (one response missing). More girls than boys miss the physical education classes (χ2(1)=9.01, p=0.002).

Regarding moderate physical activity, 714 (73.7%) respondents reported to be involved in at least one moderate physical activity. From these 714 students, 18 (2.5%) did not report on the activity(ies) performed. Of the remaining 696 respondents, 304 (43.7%) reported one activity only, 265 (38.1%) reported 2 activities, 104 (14.9%) reported 3 activities, 20 (2.9%) reported 4 activities, 1 (0.01%) reported 5 activities and 2 (0.03%) reported 6 activities. The mean number of moderate activities per student was significantly higher for girls (mean±SD=1.49±1.17) compared to boys (mean±SD=1.23±0.97; p=0.003). The activities most reported were cycling (n=473, 66.2%) and walking to/from school (n=343, 48.0%). When considering the distribution of boys and girls per activity, it was found that more boys than girls reported cycling and skating and more girls than boys reported roller skating, walking to/from school and walking in general (Table 1). Nevertheless, when considering total time spent in moderate physical activities, no differences were found between boys and girls (boys: mean±SD=267.94±406.15; girls: mean±SD=211.99±225.22, p=0.25). Table 2 presents total time per week spent in moderate physical activity as well as total time per type of activity for the total sample.

Type of physical activity for the overall sample and comparison between boys and girls.

| Physical activity | Number (%) | Chi-square | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All respondents (n=968a) | Girls (n=501; 51.8%) | Boys (n=467, 48.2%) | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Physical activity classes | 939 (97.0) | 29 (3.0) | 478 (95.4) | 23 (4.6) | 461 (98.7) | 6 (1.3) | χ2(1)=9.01, p=0.002 |

| Moderate PAb | 714 (73.7) | 254 (26.3) | 374 (74.7) | 127 (25.3) | 340 (72.8) | 127 (27.2) | χ2(1)=0.43, p=0.559 |

| Cycling | 473 (66.2) | 215 (57.5) | 258 (75.9) | χ2(1)=26.95, p<0.001 | |||

| Roller skating | 51 (7.1) | 37 (9.9) | 14 (4.1) | χ2(1)=8.96, p=0.003 | |||

| Skating | 82 (11.5) | 33 (8.8) | 49 (14.4) | χ2(1)=5.47, p=0.025 | |||

| Walking to/from school | 343 (48.0) | 213 (56.9) | 130 (38.2) | χ2(1)=24.99, p<0.001 | |||

| Walking | 235 (32.9) | 173 (46.3) | 62 (18.2) | χ2(1)=63.63, p<0.001 | |||

| Other | 59 (8.3) | 28 (7.5) | 31 (9.1) | χ2(1)=0.63, p=0.497 | |||

| Did not report | 18 (2.5) | ||||||

| Vigorous PAb | 575b (59.4) | 393 (40.6) | 253 (50.5) | 248 (49.5) | 322 (69.0) | 145 (31.0) | χ2(1)=34.12, p<0.001 |

| Handball | 4 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.6) | χ2(1)=1.33, p=0.515 | |||

| Running | 56 (9.7) | 30 (11.9) | 26 (8.1) | χ2(1)=2.31, p=0.156 | |||

| Martial arts | 23 (4.0) | 6 (2.4) | 17 (5.3) | χ2(1)=3.12, p=0.089 | |||

| Basket | 78 (13.6) | 25 (9.9) | 53 (16.5) | χ2(1)=5.23, p=0.027 | |||

| Ballet | 83 (14.4) | 80 (31.6) | 3 (0.9) | χ2(1)=108.04, p<0.001 | |||

| Football | 146 (25.4) | 16 (6.3) | 130 (40.4) | χ2(1)=86.70, p<0.001 | |||

| Gymnastics | 29 (5.0) | 23 (9.1) | 6 (1.8) | χ2(1)=15.45, p<0.001 | |||

| Rowing | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.9) | χ2(1)=0.59, p=0.634 | |||

| Swimming | 123 (21.4) | 65 (25.7) | 58 (18.0) | χ2(1)=4.97, p=0.031 | |||

| Volleyball | 23 (4.0) | 21 (8.3) | 2 (0.6) | χ2(1)=21.76, p<0.001 | |||

| Other | 165 (28.7) | 55 (21.7) | 110 (34.2) | χ2(1)=10.69, p=0.001 | |||

| Did not report | 6 (1.0) | ||||||

PA – physical activity.

Total time spent in each type of physical activity and in moderate and vigorous physical activities per week (in minutes).

| Physical activity | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate PA | 714 | 10 | 4100 | 244.80±327.07 |

| Cycling | 473 | 10 | 2100 | 146.60±221.83 |

| Walking to/from school | 343 | 10 | 750 | 92.08±85.04 |

| Walking | 235 | 10 | 1400 | 153.64±162.17 |

| Skating | 82 | 10 | 2160 | 178.66±323.38 |

| Roller skating | 51 | 10 | 450 | 81.84±88.08 |

| Other PA | 59 | 15 | 720 | 196.64±194.64 |

| Vigorous PA | 575 | 20 | 3120 | 349.53±306.19 |

| Handball | 4 | 100 | 480 | 273.33±192.18 |

| Running | 56 | 20 | 840 | 195.45±175.49 |

| Martial arts | 23 | 60 | 315 | 158.95±84.93 |

| Basket | 78 | 30 | 1260 | 357.73±191.95 |

| Football | 146 | 20 | 1320 | 302.19±206.07 |

| Ballet | 83 | 60 | 630 | 248.52±162.91 |

| Gymnastics | 29 | 60 | 540 | 245.39±132.81 |

| Swimming | 123 | 30 | 1110 | 189.79±212.57 |

| Rowing | 4 | 120 | 240 | 180.00±84.85 |

| Volleyball | 23 | 40 | 900 | 232.11±213.30 |

| Other PA | 165 | 30 | 1800 | 306.06±303.96 |

| Moderate+vigorous PA | 832 | 15 | 5760 | 446.35±474.07 |

PA – physical activity.

Regarding vigorous physical activities, a total of 575 (59.4%) respondents reported to participate in these activities. Of the 575 participants, 6 (1.0%) participants did not specify the activity in which they were involved. Of the remaining 569 participants, 438 (77.0%) reported one vigorous activity, 103 (18.1%) reported 2 activities, 24 (4.2%) reported 3 activities, 2 (0.04%) reported 4 activities and another 2 (0.04%) reported 5 activities. The activities most reported were football (n=146, 25.4%) and swimming (n=123, 21.4%) and a high number of participants signaled the response option “Other physical activities” (165, 28.7%). Despite the fact that more boys than girls reported to participate in vigorous physical activities (χ2(1)=34.12, p<0.001), no significant differences were found in the mean number of vigorous activities per student between genders (boys: mean±SD=1.28±0.57; girls: mean±SD=1.30±0.62; p=0.34). When considering the distribution of boys and girls per activity, more boys than girls reported playing basket, football and other activities, while more girls than boys reported ballet, gymnastics, swimming and volleyball (Table 1). In addition, boys spent more time in vigorous physical activities than girls (boys: mean±SD=381.06±317.45; girls: mean±SD=309.41±286.87, p=0.005). Table 2 presents total time per week spent in vigorous physical activity as well as time per type of activity for the total sample.

A total of 325 (35.3%) participants (from 832 valid data) reported at least 420min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week. Boys were more likely than girls to reach at least 420min of physical activity (χ2(1)=30.94, p<0.001).

A total of 128 out of 969 (13.2%) respondents did not report performing moderate or vigorous physical activity (in addition to physical education classes).

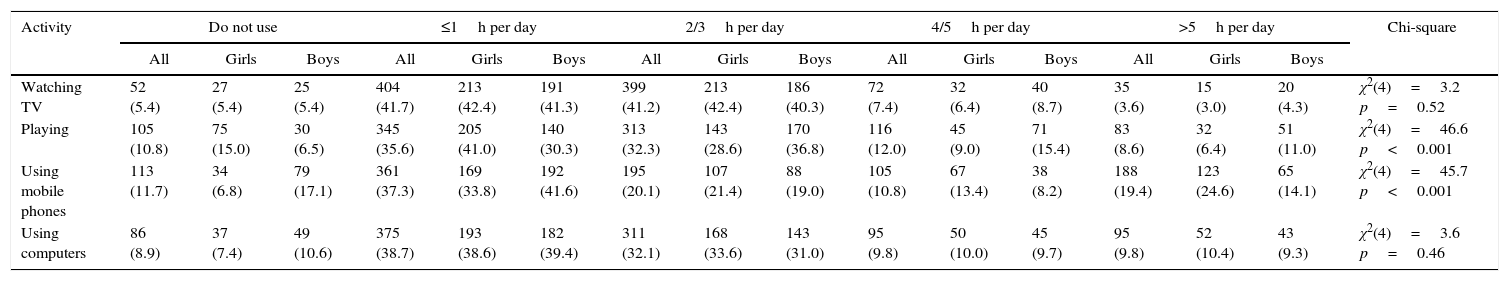

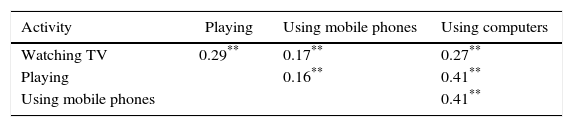

Screen based activitiesResults concerning the use of electronic devices are presented in Table 3. The percentage of participants reporting not to perform screen based activities varied between 5.4% who reported not watching TV, and 11.7% who reported not using mobile phones. A considerable percentage of participants report to spend 4h or more watching TV (11.0%), playing (20.6%), using mobile phones (30.2%) and using computers (19.6%). Boys tend to spend more time playing than girls (χ2(4)=46.6; p<0.001), while girls tend to use mobile phones more than boys (χ2(4)=45.7, p<0.001). Respondents who reported to spend more time in one screen based activity tend to also spend more time in the other screen based activities (Table 4). All but 5 respondents reported not to perform any of the four screen based activities enquired.

Daily use of electronic devices (n=962a).

| Activity | Do not use | ≤1h per day | 2/3h per day | 4/5h per day | >5h per day | Chi-square | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Girls | Boys | All | Girls | Boys | All | Girls | Boys | All | Girls | Boys | All | Girls | Boys | ||

| Watching TV | 52 (5.4) | 27 (5.4) | 25 (5.4) | 404 (41.7) | 213 (42.4) | 191 (41.3) | 399 (41.2) | 213 (42.4) | 186 (40.3) | 72 (7.4) | 32 (6.4) | 40 (8.7) | 35 (3.6) | 15 (3.0) | 20 (4.3) | χ2(4)=3.2 p=0.52 |

| Playing | 105 (10.8) | 75 (15.0) | 30 (6.5) | 345 (35.6) | 205 (41.0) | 140 (30.3) | 313 (32.3) | 143 (28.6) | 170 (36.8) | 116 (12.0) | 45 (9.0) | 71 (15.4) | 83 (8.6) | 32 (6.4) | 51 (11.0) | χ2(4)=46.6 p<0.001 |

| Using mobile phones | 113 (11.7) | 34 (6.8) | 79 (17.1) | 361 (37.3) | 169 (33.8) | 192 (41.6) | 195 (20.1) | 107 (21.4) | 88 (19.0) | 105 (10.8) | 67 (13.4) | 38 (8.2) | 188 (19.4) | 123 (24.6) | 65 (14.1) | χ2(4)=45.7 p<0.001 |

| Using computers | 86 (8.9) | 37 (7.4) | 49 (10.6) | 375 (38.7) | 193 (38.6) | 182 (39.4) | 311 (32.1) | 168 (33.6) | 143 (31.0) | 95 (9.8) | 50 (10.0) | 45 (9.7) | 95 (9.8) | 52 (10.4) | 43 (9.3) | χ2(4)=3.6 p=0.46 |

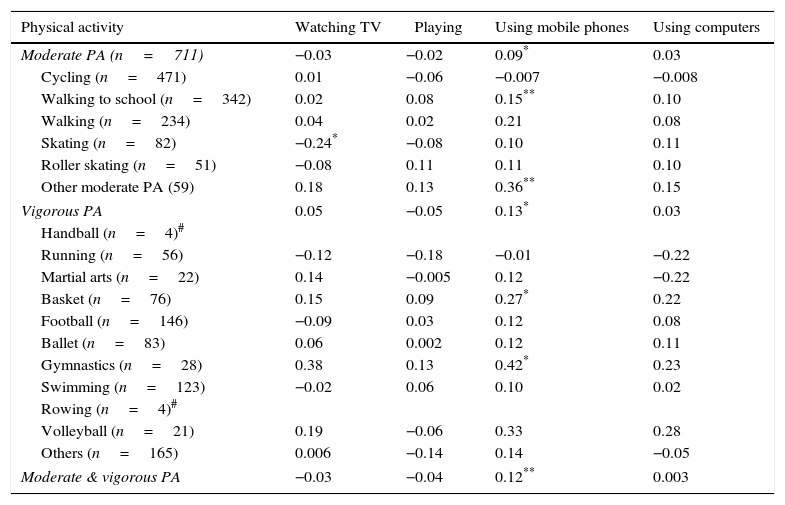

No significant differences were found between those reporting moderate or vigorous physical activity and those reporting no moderate or vigorous physical activity in terms of time spent of watching TV (χ2(4)=4.85, p=0.77), playing (χ2(4)=5.83, p=0.67), using mobile phones (χ2(4)=7.76, p=0.46) or using computers (χ2(4)=12.05, p=0.15). When correlating the amount of time spent in both moderate and vigorous physical activity and the use of electronic devices, a small but significant positive correlation was found between mobile phones and total time spent in moderate physical activity (r=0.09, p<0.05), total time spent in vigorous physical activity (r=0.13, p<0.05), total time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity (r=0.12, p<0.01), time spent in other moderate physical activities (r=0.36, p<0.01), walking to/from school (r=0.15, p<0.01), basket (r=0.27, p<0.01) and gymnastics (r=0.42, p<0.05) (Table 5), suggesting that an increase in the time spent in these physical activities is associated with increased use of mobile phones. A significant negative association was found between skating and watching TV/videos or DVDs.

Correlation between use of electronic devices and time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activities (in minutes).

| Physical activity | Watching TV | Playing | Using mobile phones | Using computers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate PA (n=711) | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.09* | 0.03 |

| Cycling (n=471) | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.007 | −0.008 |

| Walking to school (n=342) | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.15** | 0.10 |

| Walking (n=234) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| Skating (n=82) | −0.24* | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Roller skating (n=51) | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| Other moderate PA (59) | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.36** | 0.15 |

| Vigorous PA | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.13* | 0.03 |

| Handball (n=4)# | ||||

| Running (n=56) | −0.12 | −0.18 | −0.01 | −0.22 |

| Martial arts (n=22) | 0.14 | −0.005 | 0.12 | −0.22 |

| Basket (n=76) | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.27* | 0.22 |

| Football (n=146) | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Ballet (n=83) | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Gymnastics (n=28) | 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.42* | 0.23 |

| Swimming (n=123) | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Rowing (n=4)# | ||||

| Volleyball (n=21) | 0.19 | −0.06 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Others (n=165) | 0.006 | −0.14 | 0.14 | −0.05 |

| Moderate & vigorous PA | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.12** | 0.003 |

PA – physical activity.

When investigating differences in the time spent in screen based activities between those performing at least 420min of moderate to vigorous physical activities and those performing less than 240min, a significant difference was found only for mobile phones (χ2(4)=13.06, p=0.01), with those reporting less physical activity also reporting lower mobile phone usage.

DiscussionOur study results suggest a lack of association between watching TV, playing and using computers and time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity. This lack of association was present when examining the association for both total time spent in physical activity and time spent in individual modalities of physical activity, with the exception of a low negative association between skating and watching TV. In contrast, a low but significant positive association was found between mobile phones usage and time spent walking to/from school and in gymnastics and also between mobile phones usage and total time spent in moderate and vigorous physical activity, suggesting that an increase in physical activity is associated with a greater use of mobile phones. Studies investigating the association between physical activity and screen based activities report conflicting results. In a 4 years longitudinal study involving 10856 US students aged 10–15 years old, no association was found between changes in television viewing, or sedentary behaviors in general, and changes in leisure-time moderate/vigorous physical activity.12 In contrast, another 2 years longitudinal study10 that examined the relationship between changes in time spent watching TV and playing, and frequency of leisure-time physical activity for 4594 US students found that a decrease in time spent watching TV was associated with an increase in frequency of leisure-time physical activity. Nevertheless, the correlation coefficients between physical activity and watching TV were small and varied between −0.11 and −0.21. These results are in line with the significant negative association found in the present study between time spent watching TV and time spent skating. A cross-sectional study including 200615 students aged 11–15 years old from 39 different countries in Europe and North America found that the presence/absence of an association between physical activity and screen time and the strength of the association (when found) varied across type of screen based activity and country.9 There were stronger negative associations between screen-based activities and physical activities in North America and the Nordic European countries and positive or non-significant associations for East and Southern European countries. Portugal was not among the participating countries. Nevertheless, our study results are in line with the findings of Melkevic et al.,9 for the South European Countries and add to their claim that strategies to decrease sedentary behaviors and increase physical activity need to consider each country/region specificities.

In what concerns time spent in moderate physical activities, our findings are similar to the estimates of a Norwegian study including 908 children age 11–13 years old, which reported a mean time of weekly physical activity of approximately 358min.14 In what concerns vigorous physical activity, the cross nations study of Melkenik9 including countries of the South Europe found that adolescents aged 11–15 years old spent approximately 124min per week in vigorous physical activity. Differences in the age of respondents are unlikely to contribute to the distinct results as time spent in physical activity decreases with age.22 However, differences in the time period of physical activity considered for data collection may, at least partially, explain the higher mean time spent in vigorous physical activities found in the present study. While in the present study all activities performed in bouts of 10min or more were included, in the study of Melkevik,9 only activities totalizing at least 60min were considered. Furthermore, the extremely high standard deviations found in the present study highlight the wide variability of type spent in physical activity among students. The finding that boys spend more time in vigorous physical activities when compared to girls is in line with the findings of Melkevik et al.,9 Nevertheless, Melkevik et al.,9 reported that only 11% of girls and 21% of boys meet the international guidelines of at least 60min of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily,19 while in the present study this value is higher and reaches approximately 35%.

A considerable percentage of participants report to spend 4h or more watching TV (11.0%), playing (20.6%), using mobile phones (30.2%) and using computers (19.6%). A systematic review23 analyzing data from 539 independent samples reported that approximately 28% of young people spend more than 4h daily watching TV and 18% reported playing more than 4h per day. In line with the present study findings, boys were more likely to report higher levels of playing when compared to girls (30% vs. 7%, p<0.05), but contrary to our study findings, boys were significantly more likely to be high users of TV compared to girls.

Melkevik et al.,9 reported that in South European countries, 43% (95% CI=41.49–42.82%) of students spend more than 2h daily watching TV, 17% (95% CI=15.81–16.79) spend more than 2h daily playing and 15% (95% CI=14.91–15.94) spend more than 2h daily using computers. These estimates are lower than those found in the present study where the percentage of students reporting 2 or more hours in the different screen-based activities varied between 50.3% and 52.9%. Nevertheless, a study in 7725 Canadian students aged 13–17 years old,24 reported that 74% of boys and 59% of girls spent more than 2h daily in screen-based activities. These contrasting results may suggest that estimates of daily screen time may vary across countries/regions, but may also be associated with the constant evolution of electronic devices which diversity and availability to the general population increases rapidly. Similarly, in the present study the percentage of participants reporting not watching TV, playing, using mobile phones or computers varied between 5.4% and 11.7%, which are lower than those reported by Melkevik et al.,25 in a cross-national survey from 30 different countries, including Portugal. These authors found that 23% of girls and 19% of boys reported no electronic devices usage, but individual country estimates are not presented.

Taken together we believe that this study results inform on the physical activities and screen based activities in which students are involved as well as on the time they spend on them. It shows that an important percentage of students may not be performing the recommended daily dose of physical activity, highlighting the need to continue the promotion of physical activity among students. Furthermore, it adds to the existing studies that suggest that screen based activities are not displacing physical activity and that interventions targeting each of these factors (i.e. aiming at increasing physical activity and decreasing screen based time) may need to pursue different strategies.

Study limitationsOne limitation of this study is that we relied on self-reported measures for both physical activity and screen time, which could have influenced the results as they tend to be less accurate than objective measures. Furthermore, our study includes participants from a specific region of Portugal and, therefore, the generalizability to the whole country may be limited. Factors such as the family socioeconomic status, that seems to be associated with both physical activity and screen based time and vary across countries and regions,26 were not included in the present study and should be considered in future studies. In addition, it would have been interesting to study the association between physical activity and the total time spent in screen based activities to understand how it compares to the individual association between physical activity and the time spent in each of the four screen based activities considered in the present study. Nevertheless, this was not possible due to the ordinal nature of this variable.

ConclusionThis study found no association between playing and using computers and physical activity, neither when considering type of physical activity nor when considering overall time spent in physical activity. A negative association was found between watching TV and skating and a positive association was found between mobile phones use and physical activity. These findings suggest that screen time is not displacing physical activity and that interventions aiming to promote the increase of physical activity and the decrease of screen time may need to address different factors. Further studies, both quantitative and qualitative, are needed to confirm and help understand the positive association between mobile use and physical activity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors would like to thank all students that participated in the study, the Direction of Agrupamento de Escolas de Ílhavo, the Physical Education teachers and Dr.ª Fernanda Loureiro from the Centro de Saúde de Ílhavo.