Around 40–50% of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) suffer from obsessions and compulsions after receiving first-line treatments. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has been proposed as a reasonable augmentation strategy for OCD. MBCT trains to decentre from distressful thoughts and emotions by focusing on them voluntarily and with consciousness. This practice develops alternative ways to deal with obsessions, which could increase non-reactivity behaviours and, in turn, reduce compulsions. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of MBCT to improve OCD symptoms. Secondly, it pursues to investigate which socio-demographic, clinical, and neurobiological characteristics mediate or moderate the MBCT response; and identify potential biomarkers of positive/negative response.

MethodsThis study is a randomised clinical trial (RCT) of 60 OCD patients who do not respond to first-line treatments. Participants will be randomised to either an MBCT program or treatment as usual. The MBCT group will undergo 10 weekly sessions of 120min. Principal outcome: change in OCD severity symptoms using clinician and self-reported measures. Also, participants will undergo a comprehensive evaluation assessing comorbid clinical variables, neuropsychological functioning and thought content. Finally, a comprehensive neuroimaging protocol using structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging will be acquired in a 3T scanner. All data will be obtained at baseline and post-intervention.

DiscussionThis study will assess the efficacy of mindfulness in OCD patients who do not achieve clinical recovery after usual treatment. It is the first RCT in this subject examining clinical, neuropsychological and neuroimaging variables to examine the neural patterns associated with the MBCT response.

Clinical trials registration: NCT03128749.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a long-lasting psychiatric disorder in which patients experiment reoccurring interfering thoughts (obsessions) and/or the urge to neutralize them with repetitive mental or overt actions (compulsions). OCD affects around 2–3% of the general population.1 Evidence supports cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) including exposure and response prevention (E-RP) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line treatments.2 However, 40–60% of patients still present partial or non-response to those treatments.2 Moreover, around 48% of the patients who achieve remission present a new relapse after 2 years.3 Thus, developing psychological interventions that enhance gold standard treatments constitutes a plausible approach to achieve better and longer patients’ improvement.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) has been proposed as a reasonable augmentation treatment strategy of CBT in OCD patients.4–6 It has proved to be effective for major depressive disorder,7 which frequently co-exists with OCD.1 Succinctly, MBCT practice develops alternative ways to deal with obsessions, which could increase non-reactivity behaviours and, in turn, reduce compulsions. Mechanisms of action of MBCT have been proposed through the improvement in attention control, which would enhance awareness and emotion regulation.8 Better attention focusing skills improve the ability to recognize emergent emotions more promptly, making a successful exposure more likely, without avoiding those unpleasant emotions/sensations associated with obsessions.6,8 Additionally, cognitive changes related to mindfulness practice9 are linked to neuropsychological aspects affected in OCD, such as executive functions and attention.10 However, specific neuropsychological mechanisms associated with MBCT response in OCD have not yet been examined.

From a neurobiological perspective, mindfulness practice has been associated with functional and structural changes in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), insula, left hippocampus, temporoparietal junction, striatum (caudate and putamen) and fronto-limbic network (increased prefrontal activation and improved prefrontal control over amygdala responses).8 These brain regions involved in MBCT, which have already been linked with OCD psychopathology,11 underlie psychological processes like attention, emotion, and awareness.8 Parallel, disrupted emotional regulation in OCD has been associated with abnormal activations in the fronto-limbic circuit, amygdala, OFC, ACC/ventromedial PFC, putamen, insula, and occipital and middle temporal cortices.11 However, whether specific patterns of functional changes (during resting state and/or in response to specific neurocognitive tasks) can predict a better response to MCBT in OCD patients is still unknown.

Patients with OCD partially or non-respondent to first-line treatments reporting mild to moderate OCD symptoms will be enrolled in a multi-centre randomised clinical trial with an MBCT. Aims: (1) to assess MBCT efficacy on improving OCD symptoms and comorbid clinical and neuropsychological alterations; (2) to study socio-demographic, clinical, and neurobiological characteristics that mediate or moderate MBCT response; (3) to identify potential biomarkers of positive/non-response response to MBCT; (4) to study clinical, cognitive, neuropsychological mediators or moderators of functional and structural brain changes in response to MBCT.

Material and methodsThis is a prospective, multicentric, randomised controlled clinical trial approved by the Research Ethics Boards at hospitals where the study will be run. The study will be conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices guidelines.

ParticipantsSixty patients aged between 18 and 50 years diagnosed with OCD (according to DSM-5 criteria) will be recruited from the Psychiatry Department of two different hospitals. All participants should have completed a minimum of 12 cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), focused primarily on E-RP, sessions (individual or group format) and should have been under psychiatric treatment over the last year and still present significant obsessive symptoms that prevent them from achieving a full clinical recovery (global score >9 of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)).12 All participants must have a minimum level of schooling up to the age of 14 (minimum of 8 years of schooling). Participants’ exclusion criteria include: (i) an intelligence quotient (IQ) below 85, (ii) more than three pharmacological changes in the last 12 months, (iii) presence of any organic pathology and/or any neurological disease such as brain damage or epilepsy, (iv) past or current substance abuse, (v) a history of psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder and/or recent suicide attempts, (vi) previous completion of a mindfulness-based therapy course (≥8 weeks). Other affective or anxiety disorders will not be considered exclusion criteria as long as OCD is the primary diagnosis and reason for consultation.

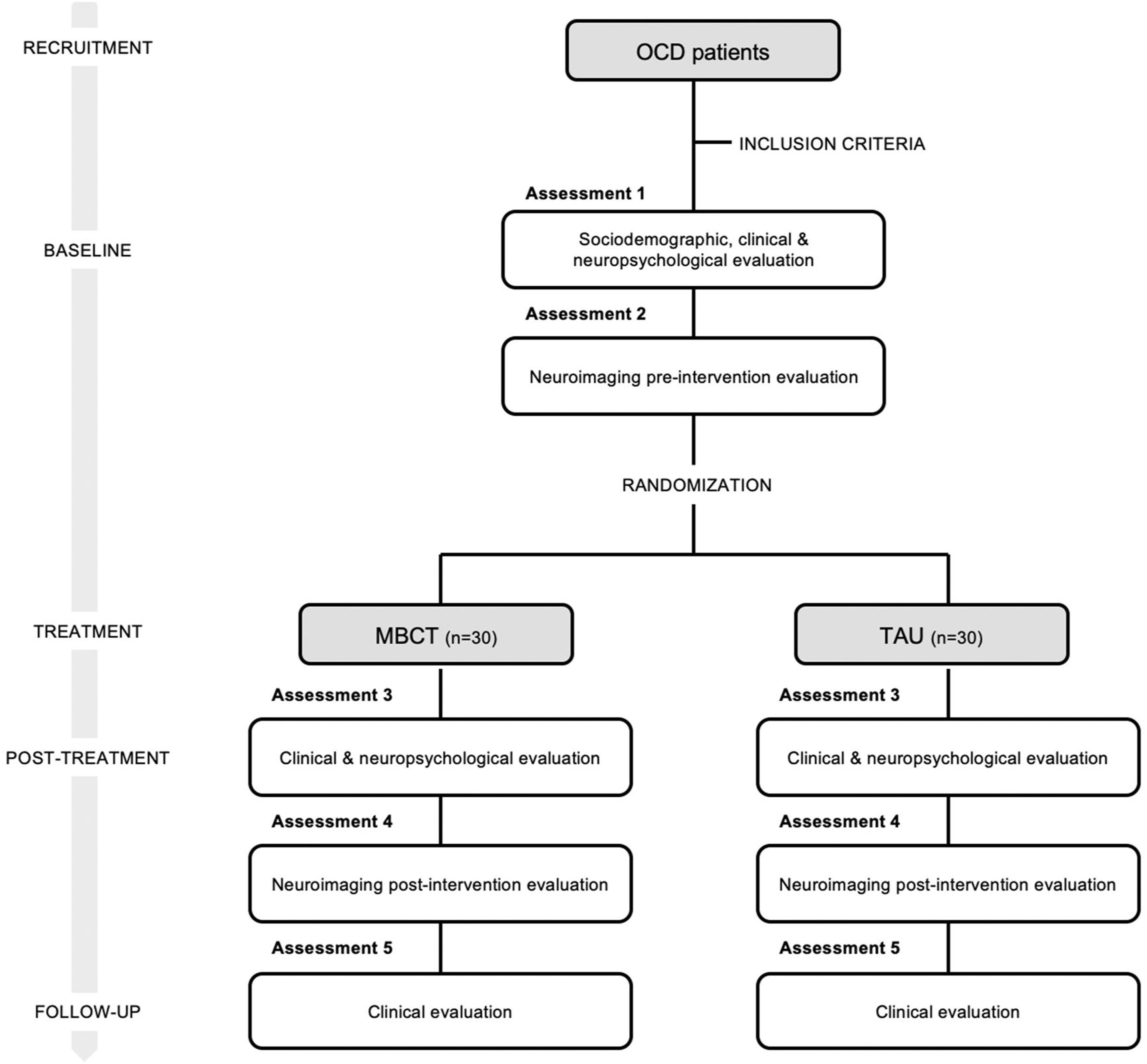

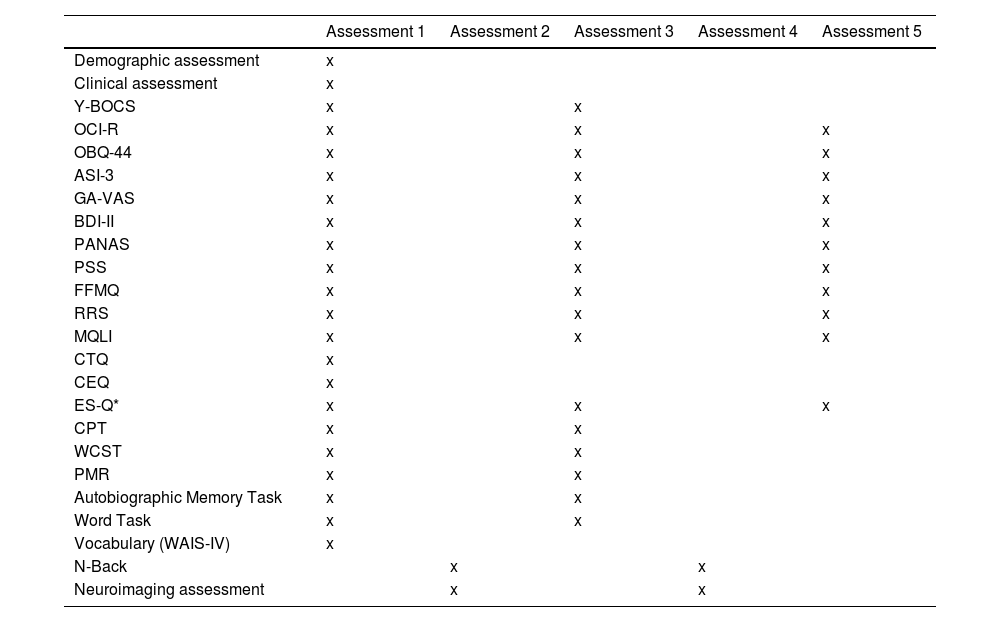

Study designClinical psychologists and psychiatrists at both hospitals will be selecting candidates to participate in this study. Participants will receive a detailed explanation of the study, and if they agree to participate, written informed consent will be obtained. All patients complying with the inclusion criteria will perform a demographic, clinical, neuropsychological, and thought content evaluation. Patients will also undergo a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test before the intervention. Then, all patients will be randomised to one of the two possible groups: the MBCT program or the treatment as usual group (TAU). Randomisation will be done through computer-generated random numbers using the excel function =RAND(), which applies simple randomisation. After 3 months, a new clinical, neuropsychological, thought content and neuroimaging evaluation will be conducted. Moreover,6 months after, we will run a clinical follow-up through self-rated scales. Table 1 summarises all measures included in each session of the assessment. The psychologists who will carry out the explorations will not be informed of which group each of the participants belongs to. These psychologists will be different from those who will be conducting the intervention. To ensure the same conditions in both intervention centres, the same measures and the same type of equipment will be used. Accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a two-sided test, 30 subjects are necessary in each treatment arm to recognize as statistically significant a minimum difference of 3.56 units between any pair of groups assuming that 2 groups exist13 (calculated with public software GRANMO). Based on our pilot data, the common deviation is assumed to be 4.5. It has been anticipated a drop-out rate of 15%. This study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Assessment measures throughout the study.

| Assessment 1 | Assessment 2 | Assessment 3 | Assessment 4 | Assessment 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic assessment | x | ||||

| Clinical assessment | x | ||||

| Y-BOCS | x | x | |||

| OCI-R | x | x | x | ||

| OBQ-44 | x | x | x | ||

| ASI-3 | x | x | x | ||

| GA-VAS | x | x | x | ||

| BDI-II | x | x | x | ||

| PANAS | x | x | x | ||

| PSS | x | x | x | ||

| FFMQ | x | x | x | ||

| RRS | x | x | x | ||

| MQLI | x | x | x | ||

| CTQ | x | ||||

| CEQ | x | ||||

| ES-Q* | x | x | x | ||

| CPT | x | x | |||

| WCST | x | x | |||

| PMR | x | x | |||

| Autobiographic Memory Task | x | x | |||

| Word Task | x | x | |||

| Vocabulary (WAIS-IV) | x | ||||

| N-Back | x | x | |||

| Neuroimaging assessment | x | x |

Note: Y-BOCS: The Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; OCI-R: Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised; OBQ-44: Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire-44; ASI-3: Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3; GA-VAS: Global Anxiety-Visual Analogue Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; FFMQ: Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; RRS: Ruminative Responses Scale; MQLI: Multicultural Quality of Life Index; CTQ: Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CEQ: Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire; ES-Q: Experiential Sample-Questionnaire; CPT: Continuous Performance Test; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; WAIS-IV: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale version IV.

Demographic characteristics such as gender, age, years of schooling, handedness, work adjustment, marital status, number of family members, and number of people providing emotional support will be assessed. Clinical assessment will include medical and psychiatric history, family history of psychiatric disorders, current pharmacological treatment, and previous psychological treatments. The Y-BOCS-II14,15 will be used to evaluate the presence and severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Also, anxiety will be assessed by a self-reported measure called Global Anxiety-Visual Analogue Scale (GA-VAS).16

In addition to these measures, a set of self-rated scales will be administered using the online application e-encuesta. The self-reported test battery will include the following scales: Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R),17 Obsessive Beliefs Questionnaire-44 (OBQ-44),18 Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3),19 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II),20 Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS),21 Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),22 Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ),23 Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS),24 Multicultural Quality of Life Index (MQLI),25 Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF),26 and Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ).27

Neuropsychological assessmentAll participants will undergo a set of neuropsychological tests that will evaluate cognitive functioning focusing on attention and cognitive flexibility.9 Sustain attention will be measured by the Continuous Performance Test (CPT28,29; from the Inquisit Test Library https://www.millisecond.com/download/library/cpt/). The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST30; will be used to assess abstract reasoning and set-shifting abilities). Phonemic verbal fluency will be evaluated with PMR (verbal fluency test adapted for Spanish speaking population31,32 and administered through E-Prime 2.0 professional (Psychology Software Tools)). Finally, premorbid intelligence will be assessed with the Vocabulary Subtest of the WAIS-IV.33

See supplementary material for psychometric properties information of clinical and neuropsychological measures.

Thought content assessmentThought content will be measured using:

- •

The Autobiographical Memory Task (adapted from previous autobiographical memory measures34) will be used to assess the autobiographical recall capacity.

- •

The Word Task (adapted for the Spanish speaking population from the Affective Norms for English Words)35,36; will be used to evaluate the language fluency and the thought content.

- •

The Experiential Sample-Questionnaire (ES-Q)37,38 is a self-reported questionnaire that will examine the content of thinking.

See supplementary material for further explanation.

Neuroimaging assessmentPre-scanner trainingBefore entering the MRI, all patients will perform a working memory test called n-back.39 In addition, there will be prior training of the Autobiographic Memory and the Self-Reference40 fMRI tasks. These tasks will allow to study the default mode network (DMN) in OCD patients and its potential changes after a mindfulness-based intervention, as both tasks imply its activation/deactivation. The Autobiographical Memory Task is a more innovative measure in which performance of the participants might be sensitive to OCD symptoms and mindfulness training. Additionally, the Self-Reference Task will provide data on the DMN using a more standardized methodology.

See supplementary material for further explanation.

In scannerStructural and functional MRI measures will be acquired using a 3 Tesla Ingenia (Philips Medical Systems) scanner equipped with a 32-channel phased-array head coil housed. The setting will include an MRI-compatible LCD (liquid crystal display) screen (BOLD screen 32, Cambridge Research Systems) and a button-box (Lumina 3G Controller, Cedrus Corporation, see supplementary material, Figs. 3 and 4) for stimulus presentation and response recording.

See supplementary material for a detailed description of tasks in the scanner.

- •

Physiological monitoring: Concurrent heart rate and oxygen saturation (O2sats) will be recorded for fMRI sequences employing an MRI compatible system (MP150, Biopac Systems, Inc.). The pulse oximeter will be placed in the participant's non-dominant hand and the signal will be recorded at 1.000Hz using Acknowledge 3.8.2 software.

A set of questions related to the patient's feelings and thoughts during the execution of the memory task within the scanner will be performed.

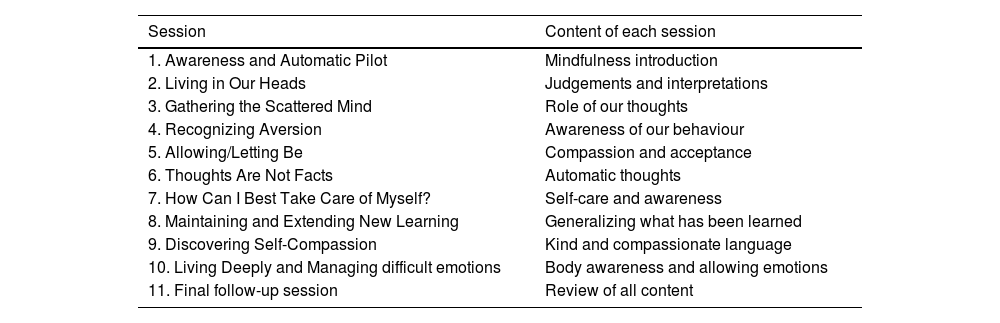

InterventionParticipants that fulfil the inclusion criteria will be randomised to one of the two possible treatment arms: MBCT (experimental group) or TAU (control group). MBCT will consist of ten weekly sessions of 120min each, distributed as follows: eight sessions of MBCT from the original validated MBCT protocol for depression,41 adapted for patients with OCD, e.g. alluding to obsessions besides rumination. Plus two extra sessions designed ad-hoc for OCD patients.42,43 During the extra sessions, therapists will evoke situations where participants had experienced obsessive thoughts and they will introduce specific meditations to develop a compassionate self, such as affectionate breathing and loving-kindness, as well as will facilitate labelling and body awareness and will teach the “soften-allow-soothe” practice. Also, informal practices such as soothing touch and self-compassion break will be suggested. All participants will be required to undergo daily training exercises at home for approximately 30–45min. After four weeks, there will be a final follow-up session (session 11). The treatment will be applied in a group format of 10–12 participants, and it will be performed by two experienced therapists in MBCT. Table 2 shows an explanation of the sessions. TAU, as the control group, will receive their usual pharmacological treatment, without adding any psychological intervention. TAU patients will be on a waitlist to receive the intervention after the study is completed.

Content of the MBCT intervention.

| Session | Content of each session |

|---|---|

| 1. Awareness and Automatic Pilot | Mindfulness introduction |

| 2. Living in Our Heads | Judgements and interpretations |

| 3. Gathering the Scattered Mind | Role of our thoughts |

| 4. Recognizing Aversion | Awareness of our behaviour |

| 5. Allowing/Letting Be | Compassion and acceptance |

| 6. Thoughts Are Not Facts | Automatic thoughts |

| 7. How Can I Best Take Care of Myself? | Self-care and awareness |

| 8. Maintaining and Extending New Learning | Generalizing what has been learned |

| 9. Discovering Self-Compassion | Kind and compassionate language |

| 10. Living Deeply and Managing difficult emotions | Body awareness and allowing emotions |

| 11. Final follow-up session | Review of all content |

The main objective of this study is to assess the MBCT efficacy on improving OCD symptoms. Y-BOCS-II will evaluate the change in OCD severity from a clinical perspective. OCI-R will assess severity change from a patient perspective. Both will be administered pre-and post-intervention.

Secondary outcomesAs a second exploratory aim, changes in cognitive, neuropsychological and neuroimaging patterns associated with an MBCT intervention will be analysed. Consequently, a range of secondary outcomes will be obtained, including: (i) changes in OBQ-44, which measures dysfunctional beliefs as perfectionism/certainty, importance/control of thoughts, and responsibility/threat estimation; (ii) change in anxiety symptomatology assessed with the ASI-3 and GA-VAS; (iii) change in the severity of depressive symptoms evaluated with BDI-II; (iv) change in positive and negative affect using the PANAS; (v) change in the perception of stress in different life situations using the PSS; (vi) change in cognitive performance; (vii) therapeutic change using the FFMQ, which assesses the central constructs of mindfulness; (viii) change in ruminative symptoms with the RRS; (ix) change in quality of life evaluated with MQLI; (x) change in resting state activity; (xi) change in grey and white matter volumes; (xii) change in brain activity when performing the Autobiographical Memory Task and the Self-Related Task. Most cognitive, neuropsychological and neuroimaging variables will be reassessed post-treatment (14 weeks from baseline) and some of them also at 6 months (see clinicaltrial.govNCT03128749 for more information).

Statistical analysesClinical analysisMBCT efficacy on OCD will be determined primarily by Y-BOCS change. Rates of responders will be calculated following the expert consensus for treatment efficacy in OCD.12,44 Such agreement operationally defines treatment response as a ≥35% reduction in Y-BOCS scores lasting for at least one week. Besides, a partial response is established as a ≥25% but <35% reduction in Y-BOCS score. All data will be analysed by means of SPSS Statistics version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical analyses will be considered significant with an α≤0.05 (two-tailed). Analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for the categorical variables will be used for between-group comparisons at baseline. Descriptive data will be reported with means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages and/or proportions for categorical variables. Longitudinal data will be computed using linear mixed-effects modelling to assess the impact of the different treatment options on the outcome measures, introducing the different sites as a random effect. Also, a random-term will be included for subjects treated as part of the same batch. The analysis will be repeated employing an intent-to-treat analysis. The rates of patients achieving response in both groups (MBCT vs TAU) will be compared using Fisher's exact test. Correction for multiple comparisons will be applied for the secondary outcomes.

Neuroimaging analysisImaging data will be analysed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM 12; Welcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, UK). Data pre-processing will consist of slice-timing correction, realignment, anatomical image segmentation, co-registration of functional with anatomical scans, normalisation to the MNI space and smoothing. All images will be inspected for potential acquisition artefacts or excessive movement. Pre-processed fMRI data will be modelled on the subject level in a first-level analysis in which the time series of stimulus onsets will be convolved with the canonical haemodynamic response function and included in a general lineal model (GLM). Extracted measures of interest will include resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) and task-based activation of nodes within subsystems of the default mode network (DMN)45 and the cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical circuit (CSTC).11 Similarly, white (WMV) and grey matter volumes (GMV) will be obtained from segmented structural T1 images.

Contrast images will be carried forward to a second-level analysis to identify activation and connectivity patterns for all the participants in their pre-treatment measures, obtaining the profile of functional connectivity and response to the task of the sample as a single group. To assess the effects of the MBCT intervention, a within-group comparison (pre-intervention vs. post-intervention) will be performed using a paired t-test for both functional and structural imaging measures. In addition, an ANOVA will be conducted including the interaction of treatment arm by time. The same comparisons will be performed for the control group to evaluate whether the changes observed in the MBCT group can be attributable to treatment.

Multiple regression models will be used to test if potential changes in MRI metrics of interest are correlated to clinical improvement. All second-level analyses will include age and gender as covariates, with 6 head motion parameters and white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) time courses included as nuisance regressors in the analysis of functional sequences. Resultant statistical t-maps will be corrected for multiple comparisons on the voxel level employing the family-wise-error (FWE) correction (pFWE<0.05).

DiscussionThis study arises from the necessity of increasing treatment options for patients with OCD who do not achieve remission with first-line therapies. To the best of our knowledge, only 2 RCTs seeking MBCT based protocols effectiveness in OCD but without neuroimaging have been published.4,5 As far as we know, this is the first registered RCT that incorporates clinical and neuropsychological variables, and neuroimaging techniques to determine potential neurobiological correlates associated with a response to MBCT intervention.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) are considered to have beneficial effects, not only in reducing OCD symptoms but in improving patients’ quality of life as well.5,6,46 Even though some of these previous studies have some limitations, it seems that MBI interventions are promising therapeutic strategies for patients with OCD who remain to experience symptoms even after first-line therapies.4,47

The current study includes two sessions of self-compassion (SC) to the well-studied 8-week MBCT program. Considering the negative relationship between SC and OCD symptoms,48 these complimentary sessions were added. SC and certain obsessive beliefs have been observed as part of the aetiology and maintenance of the disorder.48

The clinical assessment of treatment efficacy is also innovative, including patient's and clinicians’ perspectives as primary outcomes.

The current study will analyse whether changes in cognitive variables, neuropsychological functions and neuroimaging patterns mediate and/or moderate potential clinical improvements. By doing so, the current study takes for the first time a step forward in exploring cognitive variables that have been previously associated with depression, such as autobiographical memory specificity or rumination and decentring thought patterns.49 Regarding neuropsychological assessment, there is a large body of research reporting a worse performance in executive functions tasks in OCD patients than healthy controls,10 which is associated with prefrontal cortex and striatal fMRI alterations.11 The potential improvement of executive functions after the intervention could mediate the improvement in cognitive and affective processing. Based on emerging evidence regarding MBCT effects on cognitive performance (enhancing executive functions) and neuroplastic changes in specific brain areas, which are associated with the neurobiology of OCD (ACC, PFC, PCC, insula, striatum and amygdala),8,11 we expect to find changes in OCD brain areas and circuits in response to MBCT intervention.

This study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, from a methodological point of view, a double-blind study would be ideal for decreasing participants’ biases. This condition is intrinsically complex when TAU is used as a control condition. However, a single-blind design allows controlling biases of investigators. We must emphasize that, although patients are told to not to reveal their treatment, is not possible to completely control this phenomenon. In any case, most of the questionnaires will be self-administered via the survey web platform e-encuesta, so the potential bias of the evaluating researcher will be drastically reduced. Secondly, from a clinical perspective, most participants will be under pharmacological treatment. Nevertheless, in our public national health care system, pharmacotherapy is always tried in patients with such OCD symptoms severity and withdrawing the current treatment would not be ethical.

One of the strengths of the study is the design. It is a multi-centre randomised clinical trial that would help to ensure more generalisable results. Furthermore, this is the first study where the effects of MBCT in OCD patients are analysed adopting a multifaceted approach. It will allow a wide range of analyses, including the relationship with clinical, neuropsychological, thought content, and neuroimaging data.

ConclusionIn conclusion, the rationale behind mindfulness and the data available so far suggest that MBCT is a plausible complementary intervention for OCD patients. Findings suggest that MBCT might be beneficial and acceptable for the treatment of OCD. Notwithstanding, more controlled studies are needed to increase the current evidence, given previous studies’ inconsistencies. This RCT might expand comprehension of OCD underpinnings and mindfulness mechanisms of change since we expect to observe neural correlates and response markers to MBCT. Disclosing its effectiveness for OCD treatment-resistant patients and in which particular domains, will help to direct a more personalised intervention for those patients.

Open practices statementThe study has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. It can be found in https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03128749?term=mbct&cond=OCD&cntry=ES&city=Sabadell&draw=2&rank=1.

We will make program code (neuropsychological and neuroimaging assessment) and tests and questionnaires adapted from previous measures or designed ad hoc (thought content assessment) available upon request.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

FundingThis study was supported by Carlos III Health InstituteFIS PI18/00856 and FIS PIS 19/01184 and FEDER funds (“A way to build Europe”) and Research and Innovation Taulí GrantCorporacion PT CIR2016/030.

FEDER founds and FIS PI18/00856 and PIS19/01184 covered the costs of the participants MRI scanning Research and Innovation Taulí Grant Corporation PT CIRI2016/030 covered participants costs of extra hospital visits due to study evaluations.

We thank CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support.