Immigration is a phenomenon with a significant impact on mental health. The aims of this study were to describe health care characteristics, time trends, differences among inmigrant, and diagnoses associated with new outpatient psychiatric consultation inmigrants in Segovia.

MethodsA descriptive study of new consultations with sociodemographic, health care and clinical variables computerized records from the “Antonio Machado” Mental Health Center for 2001–2002 and 2008 comparing immigrant and Spanish population. Population incidences were calculated by sex, geographic regions and countries of origin. By multivariate logistic regression assessed the relationship between ICD-10 diagnoses and immigration.

ResultsImmigrants had an average age of 10 years younger than the Spanish. Incidence rate of new consultation was always higher in women, decreased in immigrants and increased in the Spanish between 2001 and 2008. South Central Americans and Eastern Europeans had the highest and lowest rates of new visits, respectively. Bulgaria, Morocco, Romania and Poland were the countries most representative in 2008, with low incidences. Neurotic and somatoform disorders were the most common regardless of the origin of the patient. Psychotic and personality disorders were positively associated with immigration in the multivariate analysis.

ConclusionsThe attention of mental health immigrants in Segovia is characterized by young age, lower incidence of new queries with important variations between regions, and diagnostic association with processes more severe, which may reflect underdiagnosis and underutilization phenomena.

La inmigración es un fenómeno con una repercusión importante en la salud mental. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron describir características asistenciales, evolución temporal, diferencias entre inmigrantes, y diagnósticos asociados a las nuevas consultas psiquiátricas ambulatorias en inmigrantes en Segovia.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo de nuevas consultas con variables sociodemográficas, asistenciales y clínicas procedentes del registro informático del Centro de Salud Mental «Antonio Machado» para 2001–2002 y 2008 comparando población inmigrante y española. Se calcularon incidencias poblacionales por sexo, regiones geográficas y países de origen. Mediante análisis multivariante de regresión logística se estudió la asociación entre los diagnósticos CIE-10 y la inmigración.

ResultadosLos inmigrantes tuvieron una edad media 10 años menor que los españoles. La tasa de incidencia de nuevas consultas fue siempre más alta en mujeres, disminuyó en inmigrantes y aumentó en españoles entre 2001 y 2008. Centro-suramericanos y europeos orientales presentaron las mayores y menores tasas de nuevas consultas, respectivamente. Bulgaria, Marruecos, Rumania y Polonia fueron los países más representativos en 2008, con bajas incidencias. Los trastornos neuróticos y somatomorfos fueron los más frecuentes con independencia del origen del paciente. Los trastornos psicóticos y de personalidad se asociaron positivamente a la inmigración en el análisis multivariante.

ConclusionesLa atención de inmigrantes en salud mental en Segovia se caracteriza por una edad joven, una menor incidencia de nuevas consultas con diferencias importantes entre regiones, y una asociación diagnóstica con procesos más graves, lo que puede reflejar fenómenos de infrautilización e infradiagnóstico.

The migratory phenomenon has remained constant throughout human history, being one the principal driving factors for cultural and social development in all communities. Its expansion has been booming over the last few decades. Since 1980, the number of immigrants worldwide is estimated to have doubled. Currently, most immigrants live in Europe, Asia and North America.1 Europe has experienced 3 important periods of immigration in the 20th century, coinciding with the first and second world wars and with the fall of communist regimes and the Balkan War, both bringing about the movement of huge masses of people from the east to Europe. It could be considered that 2 clearly differentiated patterns of immigration exist in Europe: (1) a long tradition of immigration in northern European countries such as Germany, France, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, which are currently receiving immigrants from eastern Europe, and (2) virtually no tradition of immigration in some southern European countries such as Spain and Portugal, where the phenomenon has increased in the last 2 decades, involving mainly non-Europeans.2

The phenomenon of immigration in Spain has been a known for many centuries, but it was in the 1990s when it began to increase notably. Particularly, from the year 2000 on, our country took one of the top positions internationally in immigration due to some very intense growth. The foreign population in Spain went from less than 1% of the total in 1990, and a little more than 2% in 2000, to 13.8% in 2009, which translates to 6.5 million people in absolute terms. According to predictions, the figure could surpass 20% for immigrants at a national level in 2020. Similarly, in Segovia, a small province in Castilla and León, the number of immigrants has multiplied more than 14 times in the last decade, currently representing 13.4% of its population.3,4

The reasons for these migratory phenomena are usually of an economic or social nature, the first featured more in developed countries. We can differentiate between these 2 profiles: (1) temporary emigration of young immigrants whose objective is obtaining sufficient funds to achieve a specific purpose with the ultimate objective being to return to their country of origin, and (2) more stable emigration, usually undertaken by young couples whose objective is to begin a new life in the host country. In the first case, there is no real adaptation to the host country, resulting in few relationships between immigrants and the native population. However, in the second case, we do see adaptation, as well as integration and identification with the native values and culture.5

From a psychiatric perspective, there are several immigration factors to which we can grant great significance. Firstly, psychopathology is occasionally conditioned by cultural differences that qualify and modulate clinical expression. Immigration is also a factor that generates stress for people that feel obligated to leave their countries, customs, families, etc. This increases the probability of a psychiatric pathology appearing. Transcultural psychiatry specifically deals with trying to understand the repercussions of social and cultural differences on mental disorders.6

In this sense, there is an evident social need to develop a process of acknowledgement of and adaptation to a new reality, which has presented itself explosively in our country in the last few years. Furthermore, compared to other countries, Spain demonstrates some differential characteristics. For example, it has the largest presence of first-generation immigrants (mainly Hispanic Americans), many of them making contact with the European continent for the first time. In addition, there is an elevated number of people in an irregular administrative situation and there is an obvious need to achieve population rejuvenation. All this involves overcoming cultural, language and healthcare barriers, in which psychiatry is fully immersed.

In our country, there is not a lot of literature that contributes epidemiological information concerning mental disorders, regarding the immigration phenomenon. This study was designed to approximate this knowledge by describing the main healthcare characteristics, trends over the last decade and the assessment of the possible differences between different groups of the immigrant population and the Spanish population. Finally, our study plans included ascertaining which diagnostic typology is independently associated with immigration, in the context of psychiatric outpatient care, which currently represents 10% of all outpatient consultations sought out in specialised care in the Segovia province.

Materials and methodsThe information source for this study was the Electronic Registry System of the Antonio Machado Centre for Mental Health in Segovia, which collects information concerning specialised psychiatric outpatient care on a local level. This system contains data corresponding to variables such as family ties, sociodemographics, healthcare and referring facilities, from the computerisation of the clinical histories of patients that solicited consultations. The immigrant variable was created to differentiate between people born outside of Spain and people born on Spanish territory, to be able to compare the results. The registries for new consultations were selected, as they corresponded to patients seen for the first time at the Centre due to their first clinical episode or after a previous episode stopped, according to criteria established by the Department of Psychiatric Care of the General Directorate for Healthcare in the Health Department of Castilla y León (SACYL in Spanish), for the years 2001, 2002 (first semester) and 2008. The data corresponding to 2001 and the first semester of 2002 were grouped together, separate from those of 2008, to study descriptive characteristics, compare these characteristics between Spaniards and immigrants, study the diagnoses from the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) by geographic region and perform a multivariate analysis. A total of 1334 new consultations were identified for the 2001–2002 period and 1198 for 2008.

Sociodemographic (age, sex, residence environment, country of origin and geographic region of origin), healthcare (consultation trimester, referral and number of consultations per patient) and clinical variables (clinical diagnosis according to the ICD-10) were analysed. The age variable, expressed in years, was examined categorically by stratifying the ages into 3 groups (<18, 18–64 and >64), in addition to being examined as a continuous variable. The residence environment variable, categorised as rural or urban, was developed from information originally collected for the basic health zone health variable, so that it would correspond to the rural or urban environment in Segovia. Geographic region was constructed according to original country of origin, grouping countries into regions that were meant to describe different ethnic groups according to criteria previously established for Spain.1 However, the original classification proposed (European, Latin American, Maghreb, Sub-Saharan and Asian) was transformed into a more detailed alternative, containing 7 categories (Western European, Eastern European, Central and South American, North American, Maghreb, Sub-Saharan and Asian). The consultation trimester was formed by grouping patients according to their month of registration. The referring facility variable was grouped into 4 categories (primary healthcare, specialised healthcare, psychiatric hospital unit, other) according to the care centre that conducted the patient's referral to the Centre for Mental Health, as shown by the information collected originally. Clinical diagnosis corresponded to the ICD-10 classification for mental disorders, forming large diagnostic groups.

To calculate the rate of new consultations, by country and region, the populations by birth country included in the municipal register reviews developed by the National Institute for Statistics (INE in Spanish) corresponding to the Segovia province from 2001 and 2008 were used; and these populations were expressed as figures per 1000 inhabitants.4

Age and number of consultations per patient were continuous variables and the rest were categorical variables. The chi-square test or the Fisher Exact test was used in the percentage comparisons, and the Student t-test was used to compare means. The level of significance used was P<.05 in the hypothesis testing.

In an effort to establish a degree of association for the different ICD-10 diagnostic groups with the immigration phenomenon, a multivariate model was constructed using logistic regression techniques. In this model, the immigrant variable acted as a dependent variable, making each of the large diagnostic groups an independent variable, and using age, sex, residence environment and study period as independent control variables. The final model obtained reflected how each variable contributed to the fact that an immigrant received new psychiatric outpatient care, adjusted for the effect of the other independent variables explored. The results were offered as an odds ratio (OR [eβ]) with the confidence interval at 95% and the associated P-value of statistical significance.

For the statistical analysis of the data, the statistical package SPSS version 16.0 and the epidemiological program Epidat version 3.1 were used. The incidence rates mentioned were calculated using spreadsheets in Microsoft Excel 2003.

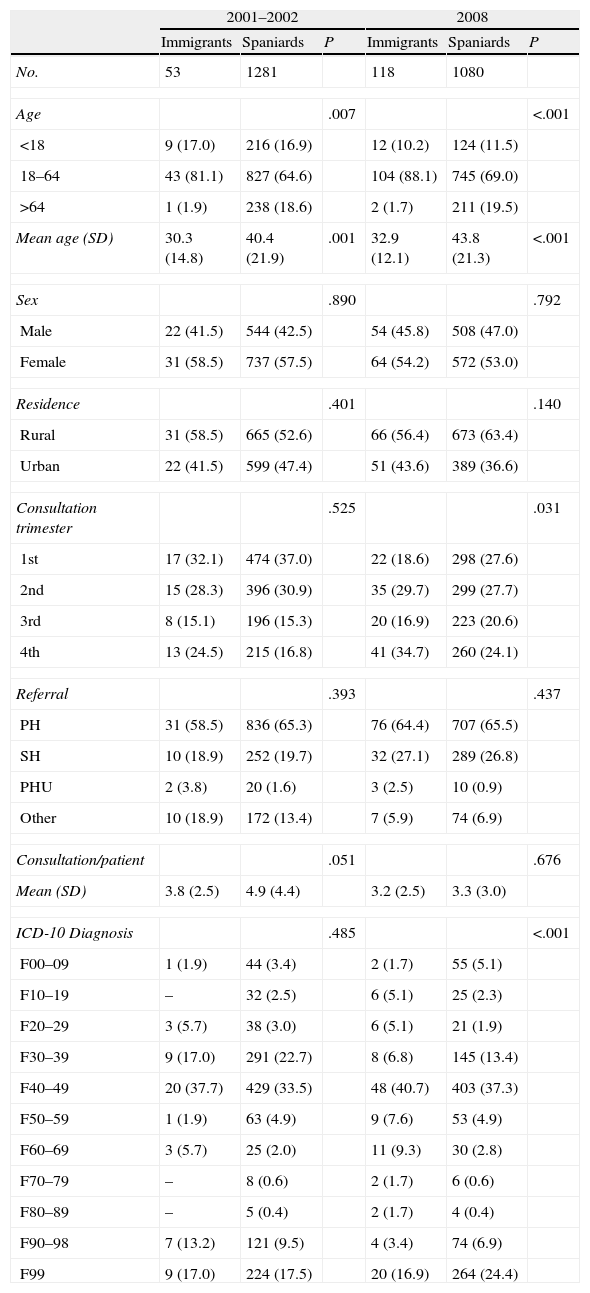

ResultsIn Table 1, we can observe the main characteristics of the immigrant and Spanish populations according to the variables studied in the 2001–2002 and 2008 periods. Among the group of immigrants that were treated, a mean age of 30 years was observed in both periods, which was younger than that of the Spanish population by about 10 years. The age group most represented in these periods was the adult group (at more than 80%), while there was a healthcare minority including patients older than 64 years. This contrasted with the Spanish population, in which this age group made up nearly 20% of the total patients. No differences were observed relating to the patients’ sex in the 2 periods studied, apart from a slight percentage increase in care for males—in both immigrant and Spanish groups—in 2008. Nor were differences observed relating to residence environment between the 2 groups. However, the percentage of Spaniards residing in rural areas that received care increased 10% in 2008 compared to 2001–2002. Distribution for the consultation trimester was similar in immigrants and Spaniards in the first period considered. In the second, an increase in consultations was observed in immigrants in the 4th trimester. The trimester with the fewest consultations was the 3rd for both groups and periods. The care facility from which patients were referred to the Centre for Mental Health was usually primary healthcare, representing between 60% and 65% of the total in both groups. In 2008, the increase in patients referred from specialised healthcare stood out, surpassing 25%. Differences were not detected between immigrants and Spaniards relating to this variable. There was a greater number of consultations per patient in the Spanish group in the first period, but this was not statistically significant. In the second period, however, the number stayed practically the same. The neurotic and somatoform disorder diagnoses were the most frequent in both periods and both groups, representing more than a third of the total. In second place were mood disorders, with a significant decrease in 2008 compared to 2001–2002, in both immigrants and Spaniards. There were no differences between the 2 groups in the first period considered, although there were in the second period, featuring greater detection of disorders due to psychotropic substance use and psychotic, behaviour and personality disorders in adults, and less detection of organic mental, mood and behaviour disorders in immigrant infancy compared to Spanish infancy.

Descriptive characteristics of new psychiatric outpatient consultations and comparison between the immigrant and Spanish populations with respect to sociodemographic, healthcare and clinical variables. Segovia, 2001–2002 and 2008; No. (%)/mean (SD).

| 2001–2002 | 2008 | |||||

| Immigrants | Spaniards | P | Immigrants | Spaniards | P | |

| No. | 53 | 1281 | 118 | 1080 | ||

| Age | .007 | <.001 | ||||

| <18 | 9 (17.0) | 216 (16.9) | 12 (10.2) | 124 (11.5) | ||

| 18–64 | 43 (81.1) | 827 (64.6) | 104 (88.1) | 745 (69.0) | ||

| >64 | 1 (1.9) | 238 (18.6) | 2 (1.7) | 211 (19.5) | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 30.3 (14.8) | 40.4 (21.9) | .001 | 32.9 (12.1) | 43.8 (21.3) | <.001 |

| Sex | .890 | .792 | ||||

| Male | 22 (41.5) | 544 (42.5) | 54 (45.8) | 508 (47.0) | ||

| Female | 31 (58.5) | 737 (57.5) | 64 (54.2) | 572 (53.0) | ||

| Residence | .401 | .140 | ||||

| Rural | 31 (58.5) | 665 (52.6) | 66 (56.4) | 673 (63.4) | ||

| Urban | 22 (41.5) | 599 (47.4) | 51 (43.6) | 389 (36.6) | ||

| Consultation trimester | .525 | .031 | ||||

| 1st | 17 (32.1) | 474 (37.0) | 22 (18.6) | 298 (27.6) | ||

| 2nd | 15 (28.3) | 396 (30.9) | 35 (29.7) | 299 (27.7) | ||

| 3rd | 8 (15.1) | 196 (15.3) | 20 (16.9) | 223 (20.6) | ||

| 4th | 13 (24.5) | 215 (16.8) | 41 (34.7) | 260 (24.1) | ||

| Referral | .393 | .437 | ||||

| PH | 31 (58.5) | 836 (65.3) | 76 (64.4) | 707 (65.5) | ||

| SH | 10 (18.9) | 252 (19.7) | 32 (27.1) | 289 (26.8) | ||

| PHU | 2 (3.8) | 20 (1.6) | 3 (2.5) | 10 (0.9) | ||

| Other | 10 (18.9) | 172 (13.4) | 7 (5.9) | 74 (6.9) | ||

| Consultation/patient | .051 | .676 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (2.5) | 4.9 (4.4) | 3.2 (2.5) | 3.3 (3.0) | ||

| ICD-10 Diagnosis | .485 | <.001 | ||||

| F00–09 | 1 (1.9) | 44 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) | 55 (5.1) | ||

| F10–19 | – | 32 (2.5) | 6 (5.1) | 25 (2.3) | ||

| F20–29 | 3 (5.7) | 38 (3.0) | 6 (5.1) | 21 (1.9) | ||

| F30–39 | 9 (17.0) | 291 (22.7) | 8 (6.8) | 145 (13.4) | ||

| F40–49 | 20 (37.7) | 429 (33.5) | 48 (40.7) | 403 (37.3) | ||

| F50–59 | 1 (1.9) | 63 (4.9) | 9 (7.6) | 53 (4.9) | ||

| F60–69 | 3 (5.7) | 25 (2.0) | 11 (9.3) | 30 (2.8) | ||

| F70–79 | – | 8 (0.6) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (0.6) | ||

| F80–89 | – | 5 (0.4) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (0.4) | ||

| F90–98 | 7 (13.2) | 121 (9.5) | 4 (3.4) | 74 (6.9) | ||

| F99 | 9 (17.0) | 224 (17.5) | 20 (16.9) | 264 (24.4) | ||

PH: primary healthcare; PHU: psychiatric hospital unit; SD: standard deviation; SH: specialised healthcare.

ICD-10 Diagnosis: F00–09: organic mental disorders; F10–19: mental disorder due to psychoactive substance uses; F20–29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–39: mood disorders; F40–49: neurotic and somatoform disorders; F50–59: behaviour disorders associated with physiological dysfunctions and somatic factors; F60–69: personality and behaviour disorders in adulthood; F70–79: mental retardation; F80–89: psychological development disorders; F90–98: behaviour disorders in infancy and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

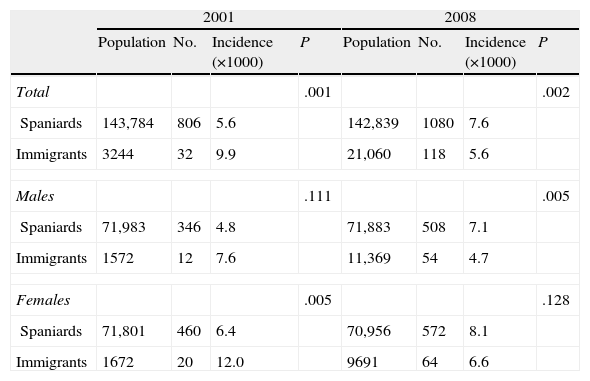

Table 2 shows the incidence rate calculation of new psychiatric outpatient consultations for the Segovia province population in 2001 and 2008. It compares the Spanish and immigrant populations according to sex. Women demonstrated higher incidence than men in both groups and periods studied. The number of immigrants and Spaniards cared for was multiplied by 3.7 and 1.3, respectively, between 2001 and 2008. The incidence rate for immigrants in 2001 was higher, by nearly double, than that for Spaniards. In 2008, however, this relation was inverted, as the rate for immigrants decreased and the rate for Spaniards increased. This result correlation was maintained when the sexes were considered separately, even though there were only significant differences for women in 2001, and for men in 2008.

Incidence rate for new psychiatric outpatient consultations according to sex in immigrant and Spanish populations. Segovia, 2001 and 2008.

| 2001 | 2008 | |||||||

| Population | No. | Incidence (×1000) | P | Population | No. | Incidence (×1000) | P | |

| Total | .001 | .002 | ||||||

| Spaniards | 143,784 | 806 | 5.6 | 142,839 | 1080 | 7.6 | ||

| Immigrants | 3244 | 32 | 9.9 | 21,060 | 118 | 5.6 | ||

| Males | .111 | .005 | ||||||

| Spaniards | 71,983 | 346 | 4.8 | 71,883 | 508 | 7.1 | ||

| Immigrants | 1572 | 12 | 7.6 | 11,369 | 54 | 4.7 | ||

| Females | .005 | .128 | ||||||

| Spaniards | 71,801 | 460 | 6.4 | 70,956 | 572 | 8.1 | ||

| Immigrants | 1672 | 20 | 12.0 | 9691 | 64 | 6.6 | ||

Incidence (×1000): incidence rate per 1000 inhabitants.

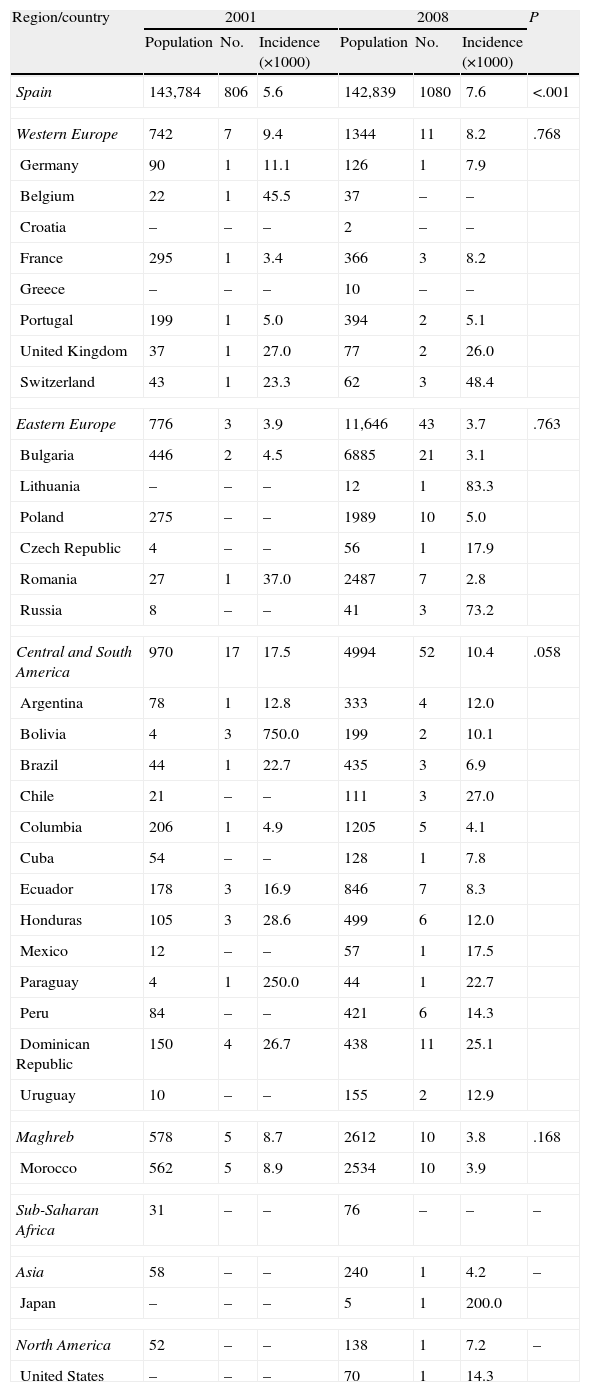

In Table 3, incidence rates of new consultations are also demonstrated, comparing the 2001 and 2008 time periods according to immigrants’ geographic region and country of origin. Central and South American immigrants presented the highest rates of incidence in the 2 years considered, with a significant decrease in 2008. On the contrary, Eastern Europeans showed the lowest incidence rate, with great stability over time. Western Europeans and Maghreb showed a non-significant decrease in incidence, the rate for the former being similar to that of the Spanish population in 2008. A significant incidence increase was detected in the Spanish group in the 7-year period studied. The countries with the highest absolute number of immigrants treated were Morocco in 2001 and Bulgaria in 2008. Excluding countries with very scarce populations in Segovia, there was great variability in incidence rates by country, especially in 2001, which was characterised by a low number of cases. In 2008, countries such as Switzerland, Chile, United Kingdom and the Dominican Republic presented the highest incidence rates.

Population incidence rate of new psychiatric outpatient consultations according to main geographic regions and countries of origin. Segovia, 2001 and 2008.

| Region/country | 2001 | 2008 | P | ||||

| Population | No. | Incidence (×1000) | Population | No. | Incidence (×1000) | ||

| Spain | 143,784 | 806 | 5.6 | 142,839 | 1080 | 7.6 | <.001 |

| Western Europe | 742 | 7 | 9.4 | 1344 | 11 | 8.2 | .768 |

| Germany | 90 | 1 | 11.1 | 126 | 1 | 7.9 | |

| Belgium | 22 | 1 | 45.5 | 37 | – | – | |

| Croatia | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | |

| France | 295 | 1 | 3.4 | 366 | 3 | 8.2 | |

| Greece | – | – | – | 10 | – | – | |

| Portugal | 199 | 1 | 5.0 | 394 | 2 | 5.1 | |

| United Kingdom | 37 | 1 | 27.0 | 77 | 2 | 26.0 | |

| Switzerland | 43 | 1 | 23.3 | 62 | 3 | 48.4 | |

| Eastern Europe | 776 | 3 | 3.9 | 11,646 | 43 | 3.7 | .763 |

| Bulgaria | 446 | 2 | 4.5 | 6885 | 21 | 3.1 | |

| Lithuania | – | – | – | 12 | 1 | 83.3 | |

| Poland | 275 | – | – | 1989 | 10 | 5.0 | |

| Czech Republic | 4 | – | – | 56 | 1 | 17.9 | |

| Romania | 27 | 1 | 37.0 | 2487 | 7 | 2.8 | |

| Russia | 8 | – | – | 41 | 3 | 73.2 | |

| Central and South America | 970 | 17 | 17.5 | 4994 | 52 | 10.4 | .058 |

| Argentina | 78 | 1 | 12.8 | 333 | 4 | 12.0 | |

| Bolivia | 4 | 3 | 750.0 | 199 | 2 | 10.1 | |

| Brazil | 44 | 1 | 22.7 | 435 | 3 | 6.9 | |

| Chile | 21 | – | – | 111 | 3 | 27.0 | |

| Columbia | 206 | 1 | 4.9 | 1205 | 5 | 4.1 | |

| Cuba | 54 | – | – | 128 | 1 | 7.8 | |

| Ecuador | 178 | 3 | 16.9 | 846 | 7 | 8.3 | |

| Honduras | 105 | 3 | 28.6 | 499 | 6 | 12.0 | |

| Mexico | 12 | – | – | 57 | 1 | 17.5 | |

| Paraguay | 4 | 1 | 250.0 | 44 | 1 | 22.7 | |

| Peru | 84 | – | – | 421 | 6 | 14.3 | |

| Dominican Republic | 150 | 4 | 26.7 | 438 | 11 | 25.1 | |

| Uruguay | 10 | – | – | 155 | 2 | 12.9 | |

| Maghreb | 578 | 5 | 8.7 | 2612 | 10 | 3.8 | .168 |

| Morocco | 562 | 5 | 8.9 | 2534 | 10 | 3.9 | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 31 | – | – | 76 | – | – | – |

| Asia | 58 | – | – | 240 | 1 | 4.2 | – |

| Japan | – | – | – | 5 | 1 | 200.0 | |

| North America | 52 | – | – | 138 | 1 | 7.2 | – |

| United States | – | – | – | 70 | 1 | 14.3 | |

Incidence (×1000): incidence rate per 1000 inhabitants.

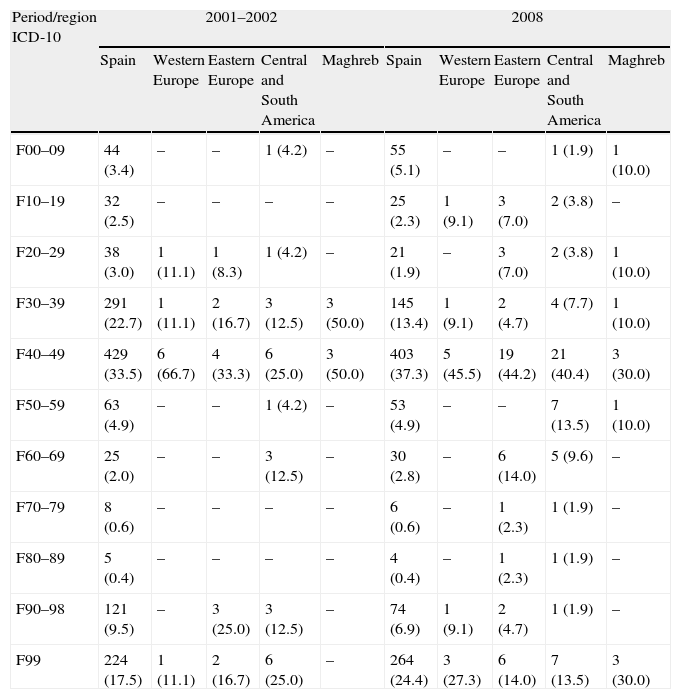

In Table 4, the differences in the main ICD-10 diagnoses can be observed, considering the main geographic regions of origin for the immigrant and Spanish populations in the 2001–2002 and 2008 periods. The results remained conditioned by the fact that, in the different regions, many of the diagnostic categories included few to no patients. If we consider that, referring to Spain, the region with the highest number of immigrants was Central and South America, we observe significant differences in 2001, with fewer mood and personality disorders. We also observe fewer organic and behaviour disorders in infancy in 2008, but more behaviour and personality disorders in adulthood. Neurotic and somatoform disorders were the most frequent in Spaniards and immigrants, independently of the region of origin considered.

Psychiatric disorder diagnosis (ICD-10) according to main geographic regions of origin. New psychiatric outpatient consultations. Segovia, 2001–2002 and 2008; no. (%).

| Period/region ICD-10 | 2001–2002 | 2008 | ||||||||

| Spain | Western Europe | Eastern Europe | Central and South America | Maghreb | Spain | Western Europe | Eastern Europe | Central and South America | Maghreb | |

| F00–09 | 44 (3.4) | – | – | 1 (4.2) | – | 55 (5.1) | – | – | 1 (1.9) | 1 (10.0) |

| F10–19 | 32 (2.5) | – | – | – | – | 25 (2.3) | 1 (9.1) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (3.8) | – |

| F20–29 | 38 (3.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (4.2) | – | 21 (1.9) | – | 3 (7.0) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (10.0) |

| F30–39 | 291 (22.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (50.0) | 145 (13.4) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (7.7) | 1 (10.0) |

| F40–49 | 429 (33.5) | 6 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | 6 (25.0) | 3 (50.0) | 403 (37.3) | 5 (45.5) | 19 (44.2) | 21 (40.4) | 3 (30.0) |

| F50–59 | 63 (4.9) | – | – | 1 (4.2) | – | 53 (4.9) | – | – | 7 (13.5) | 1 (10.0) |

| F60–69 | 25 (2.0) | – | – | 3 (12.5) | – | 30 (2.8) | – | 6 (14.0) | 5 (9.6) | – |

| F70–79 | 8 (0.6) | – | – | – | – | 6 (0.6) | – | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.9) | – |

| F80–89 | 5 (0.4) | – | – | – | – | 4 (0.4) | – | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.9) | – |

| F90–98 | 121 (9.5) | – | 3 (25.0) | 3 (12.5) | – | 74 (6.9) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (1.9) | – |

| F99 | 224 (17.5) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (16.7) | 6 (25.0) | – | 264 (24.4) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (14.0) | 7 (13.5) | 3 (30.0) |

ICD-10 Diagnosis: F00–09: organic mental disorders; F10–19: mental disorder due to psychoactive substance uses; F20–29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–39: mood disorders; F40–49: neurotic and somatoform disorders; F50–59: behaviour disorders associated with physiological dysfunctions and somatic factors; F60–69: personality and behaviour disorders in adulthood; F70–79: mental retardation; F80–89: psychological development disorders; F90–98: behaviour disorders in infancy and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

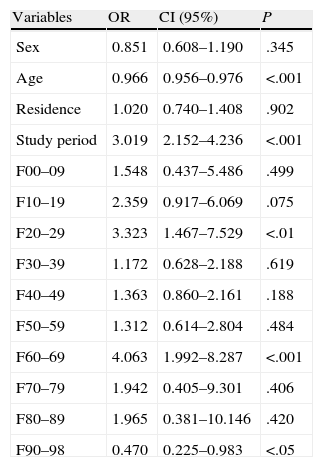

Table 5 shows the results obtained after applying the multivariate analysis. As can be observed, the presence of the diagnostic groups F20–29 (schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders) and F60–69 (personality and behaviour disorders in adults) are significantly associated with immigrant patients; however, groups F90–98 (behaviour disorders in children and adolescents) are associated with care for non-immigrant patients. Regarding the control variables, increased age was inversely correlated with immigration, which also conveys its relationship with treatment for Spanish patients. On the contrary, in 2008, we found that the probability of treating an immigrant patient increased. The rest of the independent variables, both diagnostic and control, were not significantly associated with healthcare for immigrants.

Diagnostic categories and control variables associated with new psychiatric outpatient consultations in immigrants. Multivariate logistic regression analysis. Segovia, 2001–2002 and 2008.

| Variables | OR | CI (95%) | P |

| Sex | 0.851 | 0.608–1.190 | .345 |

| Age | 0.966 | 0.956–0.976 | <.001 |

| Residence | 1.020 | 0.740–1.408 | .902 |

| Study period | 3.019 | 2.152–4.236 | <.001 |

| F00–09 | 1.548 | 0.437–5.486 | .499 |

| F10–19 | 2.359 | 0.917–6.069 | .075 |

| F20–29 | 3.323 | 1.467–7.529 | <.01 |

| F30–39 | 1.172 | 0.628–2.188 | .619 |

| F40–49 | 1.363 | 0.860–2.161 | .188 |

| F50–59 | 1.312 | 0.614–2.804 | .484 |

| F60–69 | 4.063 | 1.992–8.287 | <.001 |

| F70–79 | 1.942 | 0.405–9.301 | .406 |

| F80–89 | 1.965 | 0.381–10.146 | .420 |

| F90–98 | 0.470 | 0.225–0.983 | <.05 |

The reference categories in the categorical variables are as follows: sex (female), residence (rural), study period (2001–2002), diagnostic categories (no.).

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

ICD-10 Diagnosis: F00–09: organic mental disorders; F10–19: mental disorder due to psychoactive substance uses; F20–29: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; F30–39: mood disorders; F40–49: neurotic and somatoform disorders; F50–59: behaviour disorders associated with physiological dysfunctions and somatic factors; F60–69: personality and behaviour disorders in adulthood; F70–79: mental retardation; F80–89: psychological development disorders; F90–98: behaviour disorders in infancy and adolescence; F99: unspecified mental disorder.

The relationship between immigration and mental health has been formulated, from the possibility of positive selection (in which individuals that emigrate would be the most able and healthy) to negative selection (in which emigrating people would have a profile of instability and impairment in personal and social relationships), and the results of the different studies are contradictory.7,8 Even though it is currently admitted that immigration itself, in appropriate conditions, does not produce psychiatric pathology, it undoubtedly involves a stressful life situation when what is called migratory grief takes place, in which the individual experiences the loss of important elements—family, identity, status, language, culture, etc.—in addition to the difficulties of adapting to a new country and socio-cultural environment.9 Although the great psychiatric syndromes are universally present, socio-cultural factors may condition their clinical expression, generating different forms of manifestation. The aetiological and symptomatic conceptualisations of illness and its dimensions differ both ethnically and culturally, determining the symptomatic definition and the pathological consideration. Other limiting factors in understanding mental disorders in immigrants are language difficulties and the preservation of confidentiality.

Mild adaptive disorders with anxiety and depression are probably the most frequent in immigrants. Upon evaluating depressive disorders, we find cultural differences in clinical expression. Examples of this are experiencing the feeling of guilt as a paranoid ideation or needing protection against revenge in the Maghreb culture. There is also somatisation in some cultures, a mechanism of emotional expression, with an elevated prevalence of insomnia–headache–fatigue in depressed patients.10 Some authors speak of a specific diagnosis associated with emigration called “Ulysses syndrome”,11 characterised by chronic stress to which multiple stressors contribute, producing anxious-depressive, somatoform and conversion symptomatology. In some studies, emigrants obtained higher scores than natives on anxiety and depression scales, but they sought out psychosocial and medical services less frequently.12 Another pattern of symptoms related to immigration is post-traumatic stress disorder, especially in war refugees and victims of political torture and repression. This is also present in racial discrimination and unemployment.

Regarding psychosis, some studies found an increased incidence rate in immigrants, related to religious and spiritual beliefs with the presence of hallucinations and delirium, to continuous exposure to discrimination and racism leading to increased paranoid states, and to diagnostic error because of prejudices and poor understanding of the culture of their country of origin.13 The migratory process is considered to be 1 of the main risk factors in developing psychosis. Correlation measurements between 2.7 and 4.8 have been detected in meta-analyses, second only to family history of psychosis.14 These data are compatible with our results, as psychotic disorders were associated with immigrant patients between 1.5 and 7.5 times more than in Spaniards.

Although the increase in the number of immigrants in Spain raises the possibility of excess demand in healthcare and economic imbalances,15 less use of services has been found for immigrants in primary healthcare. This lower use is attributed to the healthy immigrant hypothesis.16 There is also under-use of services by immigrants in psychiatric healthcare in areas such as urgent hospital care.17 Our results also reflected this fact, as the incidence rate of new consultations in this population was reduced to half of what it was, despite the notable increase in the immigrant population. On the contrary, the incidence rate for Spaniards in 2008 increased.

In 2009, more than 60% of the immigrants residing in Segovia were European, 25% from the Americas—mainly South America—and the rest were African. By country, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania and Morocco stood out, making up 2/3 of the total. The first 2 countries mentioned represented more than 4% and 1% of the Segovia population, respectively. These percentages were higher than those found in Spain and Castilla y León.4 In 2008, Central and South American immigrants presented the highest incidence rate, nearly 3 times higher than Eastern Europeans and Maghrebi, and higher than the rate for Western Europeans and Spaniards. The great variability detected in the individual countries—with very low incidence rates in the 4 most representative countries—remains overshadowed by the small numbers in some countries that produce extremely unstable incidence rates. This fact can hardly be interpreted as higher mental morbidity in certain populations. It may be better interpreted as diversity in the clinical visit patterns and healthcare access between different groups of immigrants, as studies in other countries have suggested under the hypothesis of different healthcare use and the presence of institutional barriers.18 There may exist a phenomenon of underdiagnosis of mild psychiatric pathologies in immigrants, as more severe pathologies, such as psychotic processes and personality disorders in adults, are referred to or treated in mental health units. Other processes such as behaviour disorders in children would be poorly recognised and undertreated, as our results reflected.

Comparing our results with those from similar studies in our country, we found that 3.8% of the consultations solicited in Segovia in 2001 corresponded to immigrants, compared to 3.2% and 5.3% found in 2 mental health centres in Madrid for similar time periods.19,20 The following can all be considered coincidental characteristics: the mean age (between 30 and 38 years), the presence of women (between 50% and 75%), the main referral from primary healthcare facilities (between 58% and 100%) and the diagnoses of anxiety, depressive and adaptive disorders being the most frequent (between 55% and 80%). The population incidence rate of new consultations detected in 1 of the articles mentioned20 was similar to our results (6.5 vs 9.9 per 1000 habitants). Other community, observational and transversal studies describe the prevalence of mental pathology in immigrants in Spain.21 The different objectives and populations being studied conditioned divergent results among them. In some studies, illegal South American22,23 and Maghreb and Hindustani24 populations are studied. One study classified the problems found according to a determined taxonomy25 and 2 assessed the degree of depression and anxiety using different instruments.24,26 The mean age was found to be between 27 and 39 years, as in our study. There was great diagnostic variability with depressive, anxiety and adaptive disorders being the most frequent. The first 2 were observed between the 5.4% and 40.7% range in which our results were found.

We can consider the fact that our study explores time trends of the immigration explosion in Spain (beginning and end of 2000s) to be 1 of its advantages. It also covers the entire provincial framework (the only reference centre for psychiatric outpatient care in Segovia), allowing variables like rural or urban distribution of the patients to be analysed. This makes it possible for the calculation of incidence rates in the population for new consultations as the geographic and time frameworks to be well defined, both globally and by geographic region and country. Furthermore, the availability of information allows the results obtained between immigrants and Spaniards to be compared, in terms of the main variables.

We can consider the small number of existing cases to be a limitation of this study, especially during the first period studied, when comparisons—such as diagnoses by region or time differences between countries—of disaggregated data was difficult due to the little to no patient assignment in some categories, which impeded the application of comparative statistical techniques. The use of large diagnostic groups from the ICD-10 also made comparison of our results with those of other studies difficult, as the latter used more specific diagnoses.

Among the conclusions reached from this study, the following stood out: the absence of significant differences between immigrants and Spaniards in the main variables, except the younger mean age in immigrants, and a diagnostic differentiation between both groups that was detected in the multivariate analysis, with a lower incidence rate for new consultations in the immigrant population compared to the native. Even though immigration in Segovia currently consists of Eastern Europeans, mainly Bulgarians, Romanians and Polish, the highest incidence rate of new psychiatric consultations corresponded to Central and South Americans, a result that may represent access barriers. Due to the increasing importance and repercussions of immigration concerning mental healthcare, it is necessary to perform studies with more detailed and specific information to make it possible to ascertain differential characteristics and adapt our health system to the demographic reality.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sendra-Gutiérrez JM, et al. Asistencia psiquiátrica ambulatoria en la población inmigrante de Segovia (2001–2008): estudio descriptivo. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2012;5:173–82.