Despite the existence of effective evidence-based treatments for the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the therapeutic approach to this disease remains suboptimal. The availability of a therapeutic pharmacological guideline for OCD could help to improve the management of the disease in our setting and to reduce the burden of disease for the patient. With the sponsorship of the Spanish Society of Psychiatry, a group of experts has developed a guideline for the pharmacological treatment of OCD based on the recommendations of existing guidelines and following the methodology of the ADAPTE Collaboration. This article summarises the process of preparing this guideline and the recommendations adopted by consensus by a guideline panel grouped into five areas of interest: acute treatment, duration of treatment, predictors of response and special symptoms, partial response to lack of response to treatment, and special populations.

A pesar de la existencia de tratamientos efectivos basados en la evidencia para el tratamiento del trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo (TOC), el abordaje de esta enfermedad sigue siendo subóptimo. Disponer de una guía terapéutica farmacológica del TOC puede ayudar a mejorar el manejo de la enfermedad en nuestro entorno y contribuir a reducir la carga de la enfermedad para el paciente. Con el patrocinio de la Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría un grupo de expertos ha desarrollado una guía para el tratamiento farmacológico del TOC a partir de algunas guías existentes siguiendo la metodología de la ADAPTE Collaboration. En este artículo se resume el proceso de elaboración de esta guía y las recomendaciones adoptadas por consenso por el grupo elaborador de las guías agrupadas en 5 áreas de interés: tratamiento agudo, duración del tratamiento, predictores de respuesta y síntomas especiales, respuesta parcial a falta de respuesta al tratamiento y poblaciones especiales.

Although there are effective evidence-based treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), many studies indicate that the approach to this disease remains less than ideal. Among patients receiving care, less than 40% receive therapy specific for OCD and less than 10%, evidence-based treatment.1,2

Having a therapeutic pharmacological guideline for OCD available could help to manage the disease in our setting and to reduce the burden of the disease for the patient.3 With the sponsorship of the Spanish Society of Psychiatry (Spanish acronym SEP), a group of experts has developed a guideline for the pharmacological treatment of OCD based on several existing guidelines and following the methodology of the ADAPTE Collaboration.

Material and methodsThe ADAPTE methodDeveloping and updating quality clinical practice guidelines requires a significant investment in resources. At the same time, many organisations around the world prepare guidelines on the same health problem. To take advantage of existing guidelines and reduce the duplication of effort, guideline adaptation has been proposed as an effective alternative to de novo development of therapeutic guidelines.4

Adapting guidelines is a systematic process that attempts to endorse or modify guidelines developed in one setting to apply and implement them in another. This adaptation process comprises three stages4: (1) start-up stage, in which the skills and resources needed to carry out the process are identified; (2) adaptation stage, in which the specific subjects or questions that the guideline should address are chosen, guidelines are sought, their quality is assessed, the guidelines to be used as evidence sources are chosen, and the process of compilation (and adaptation of the recommendations compiled, if applicable) is conducted; and (3) end stage, in which opinions of the decision makers affected by the guideline are obtained to update it and create the final document. The full guideline development manual based on the ADAPTE process can be consulted elsewhere.4

Start-up stageThe project was carried out by a SEP-selected group of experts. The guideline preparation group (GPG) included 9 psychiatrists (AI, DS, ER, JB, JMM, JSR, MBG, MPAO and MPGP) experienced in treating patients with OCD, a clinical pharmacologist (CAG) and a research methodology expert (FRV). At the GPG's first face-to-face meeting, the scope and key aspects of the guideline were established (Table 1).

Key aspects addressed in preparing the guideline for pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults.

| 1. | Acute treatment:Psychopharmacological treatment vs psychotherapy vs combined treatmentEfficacy, safety and tolerability of the psychopharmacological treatments |

| 2. | Duration of treatment |

| 3. | Predictors of response and special symptoms |

| 4. | Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with partial response or lack of response to the treatment:Treatment optimisation or substitutionAugmentationOther therapeutic options |

| 5. | Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in special populations:Elderly patientsWomen that are pregnant or breast-feedingPsychiatric comorbidity |

A search for guidelines relevant to the pharmacological treatment of OCD was performed on the following sources: National Guidelines Clearinghouse, Guidelines International Network, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Canadian Medical Association, New Zealand Guidelines Group, Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination University of York, American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines, World Health Organization, The International College of Psychopharmacology, World Psychiatric Association, European College of Neuropsychopharmacology and World Federation of Biological Psychiatry.

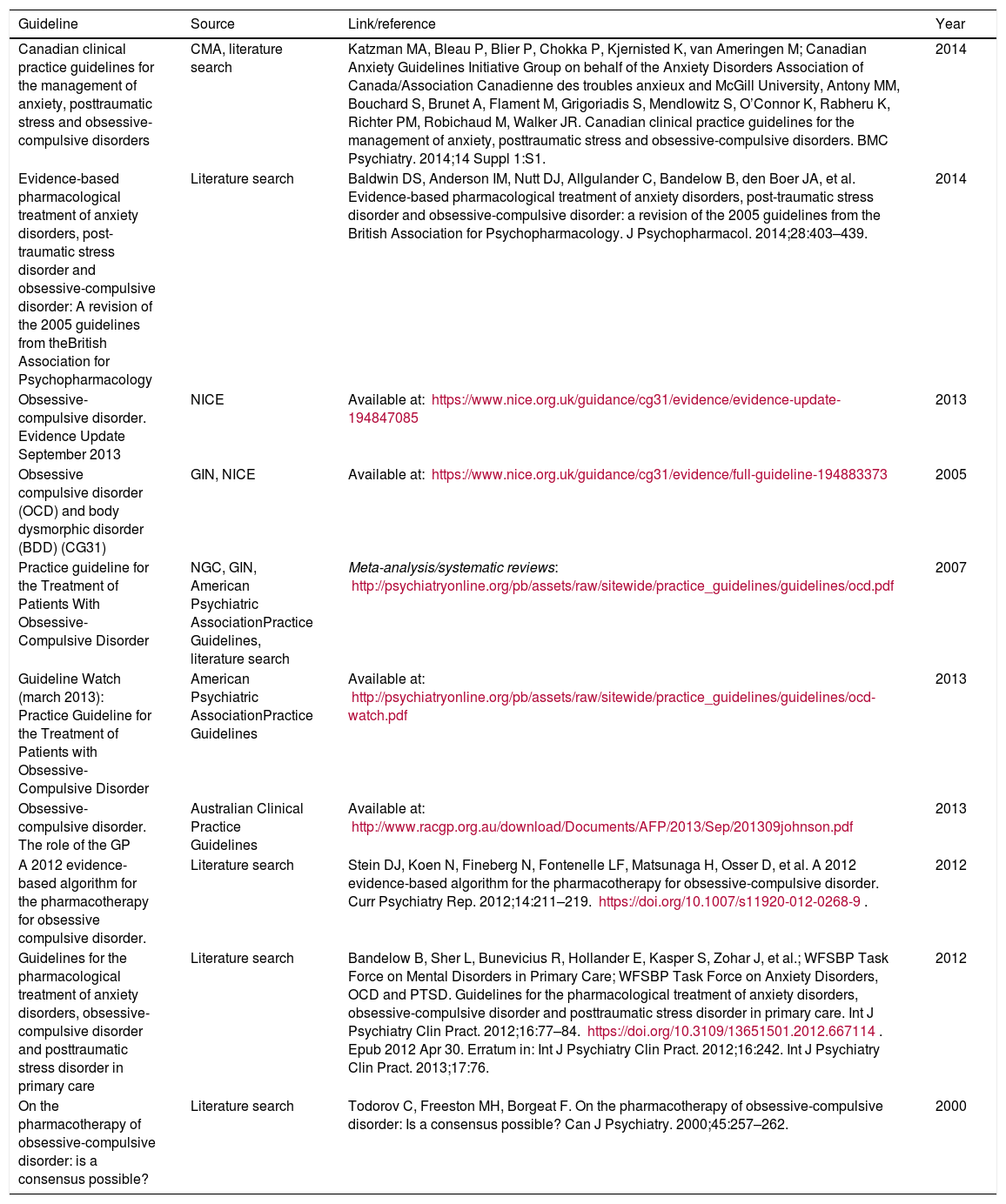

The initial selection criteria for the guidelines were as follows: cover the pharmacological treatment of OCD and include adults in the target population of the guideline. Ten documents5–14 (Table 2Table 2) were found in the initial search. Two were excluded because they did not involve clinical practice guidelines.12,13 The remaining 8 documents selected for assessment spanned 6 guidelines: the 2005 United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline8 and its 2013 update,7 the 2007 United States American Psychiatric Association guideline10 and its 2013 update,9 a Canadian clinical practice guideline,5 the British Association for Psychopharmacology guideline,6 the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guideline14 and a consensus carried out by a group of international experts.11

Guidelines, consensuses and others documents from the search for clinical practice guidelines on obsessive-compulsive disorder.

| Guideline | Source | Link/reference | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders | CMA, literature search | Katzman MA, Bleau P, Blier P, Chokka P, Kjernisted K, van Ameringen M; Canadian Anxiety Guidelines Initiative Group on behalf of the Anxiety Disorders Association of Canada/Association Canadienne des troubles anxieux and McGill University, Antony MM, Bouchard S, Brunet A, Flament M, Grigoriadis S, Mendlowitz S, O’Connor K, Rabheru K, Richter PM, Robichaud M, Walker JR. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14 Suppl 1:S1. | 2014 |

| Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from theBritish Association for Psychopharmacology | Literature search | Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Allgulander C, Bandelow B, den Boer JA, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:403–439. | 2014 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Evidence Update September 2013 | NICE | Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31/evidence/evidence-update-194847085 | 2013 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) (CG31) | GIN, NICE | Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31/evidence/full-guideline-194883373 | 2005 |

| Practice guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | NGC, GIN, American Psychiatric AssociationPractice Guidelines, literature search | Meta-analysis/systematic reviews: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd.pdf | 2007 |

| Guideline Watch (march 2013): Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | American Psychiatric AssociationPractice Guidelines | Available at: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd-watch.pdf | 2013 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The role of the GP | Australian Clinical Practice Guidelines | Available at: http://www.racgp.org.au/download/Documents/AFP/2013/Sep/201309johnson.pdf | 2013 |

| A 2012 evidence-based algorithm for the pharmacotherapy for obsessive compulsive disorder. | Literature search | Stein DJ, Koen N, Fineberg N, Fontenelle LF, Matsunaga H, Osser D, et al. A 2012 evidence-based algorithm for the pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:211–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0268-9. | 2012 |

| Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care | Literature search | Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, Hollander E, Kasper S, Zohar J, et al.; WFSBP Task Force on Mental Disorders in Primary Care; WFSBP Task Force on Anxiety Disorders, OCD and PTSD. Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16:77–84. https://doi.org/10.3109/13651501.2012.667114. Epub 2012 Apr 30. Erratum in: Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2012;16:242. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17:76. | 2012 |

| On the pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: is a consensus possible? | Literature search | Todorov C, Freeston MH, Borgeat F. On the pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Is a consensus possible? Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:257–262. | 2000 |

CMA: Canadian Medical Association; GIN: Guidelines International Network; NGC: National Guidelines Clearinghouse; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

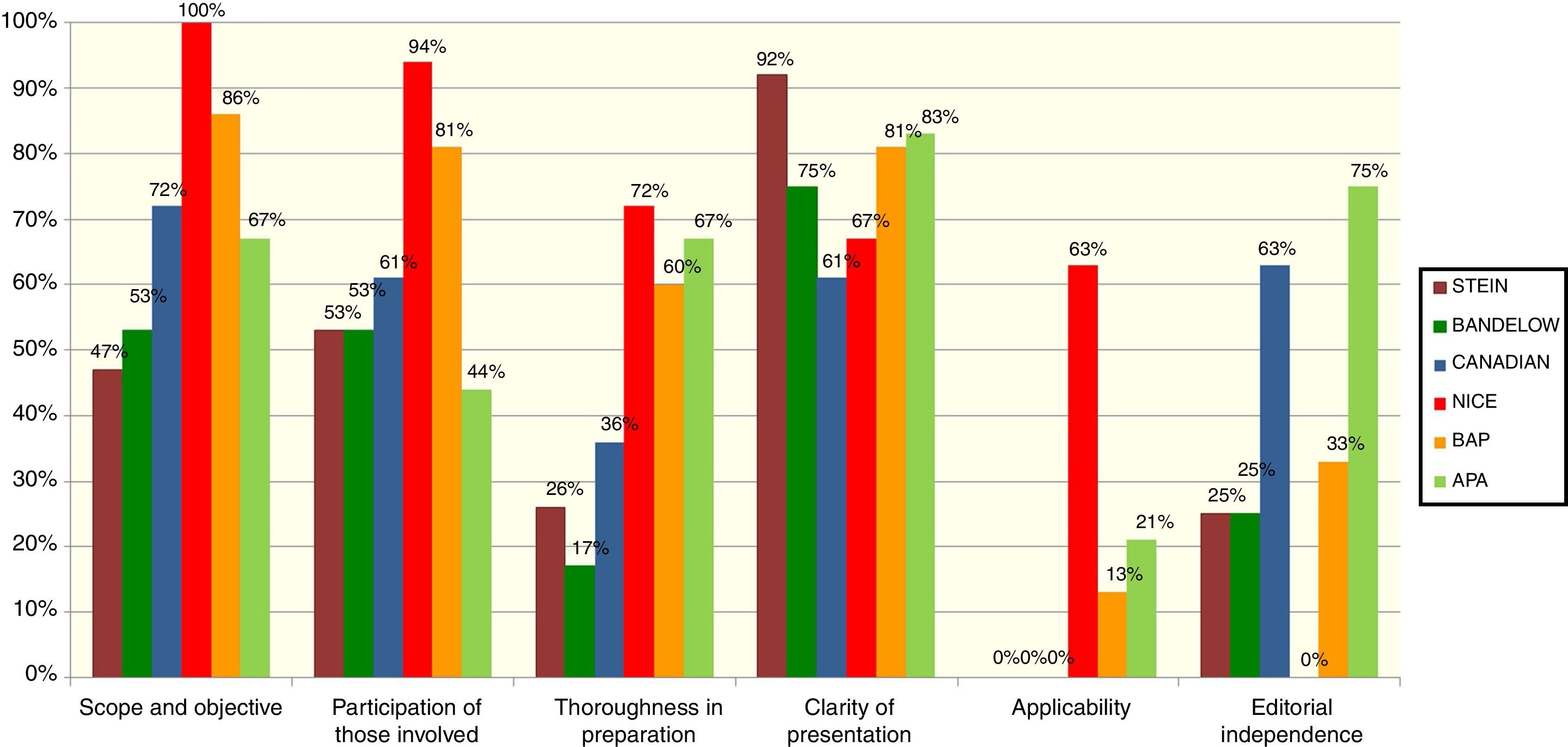

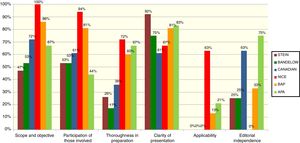

The 6 guidelines initially chosen were individually assessed by 10 GPG members, using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)15 assessment tool. The AGREE II is a generic instrument that assesses the guideline preparation and communication process. The 23-item tool is answered using a 7-point scale; the 23 items are grouped in 6 quality-related dimensions: scope and objective, participation of those involved, thoroughness in the preparation, clarity of presentation, applicability and editorial independence. The instrument also includes an assessment of overall guideline quality and a question about whether the assessor would recommend using the guideline, with or without modifications, or would not recommend it. For their training in guideline assessment, all the reviewers used the tutorial proposed by AGREE II (available at: http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tools/). Scores were calculated based on the AGREE II recommendations.

The results of the assessment of the 6 guidelines are presented in Fig. 1. In a face-to-face meeting, the GPG members selected the 4 guidelines that, in the assessors’ opinion, presented the best quality based on the score in thoroughness of preparation and that were recommendable—with modifications—for use. These guidelines were the 2005 United Kingdom guideline of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence8 (called NICE from now on) and its 2013 update,7 the 2007 United States American Psychiatric Association (APA) guideline10 and its 2013 update,9 the Canadian clinical practice guideline for the management of some anxiety disorders (henceforth called “Canadian”),5 and the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guideline.6

Assessment of the clinical practice guidelines initially selected using the AGREE II tool.

APA, Practice guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Guideline Watch (March 2013): Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder9,10; Bandelow, Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care14; BAP, Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: A revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology6; Canadian, Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders5; NICE, Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphic disorder (ADD) (CG31) and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Evidence Update September 20137,8; Stein, A, 2012 evidence-based algorithm for the pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder.11

The 10 assessors compiled the recommendations from the 4 source guidelines (NICE, APA, Canadian and BAP) in a compiled in a recommendation array that included the specific recommendations included in the guideline one by one, the source (that is, the guideline from which the recommendation came) and any comments. All the recommendations from the 4 different guidelines were compiled for each of the subjects covered by the corresponding guideline. Next, the GPG held two teleconferences and a face-to-face meeting to discuss the recommendations and select them based on the consistency of the recommendation with current evidence and its acceptability to or applicability in our setting. Using an informal consensus system, each recommendation was finally adopted, modified or rejected.

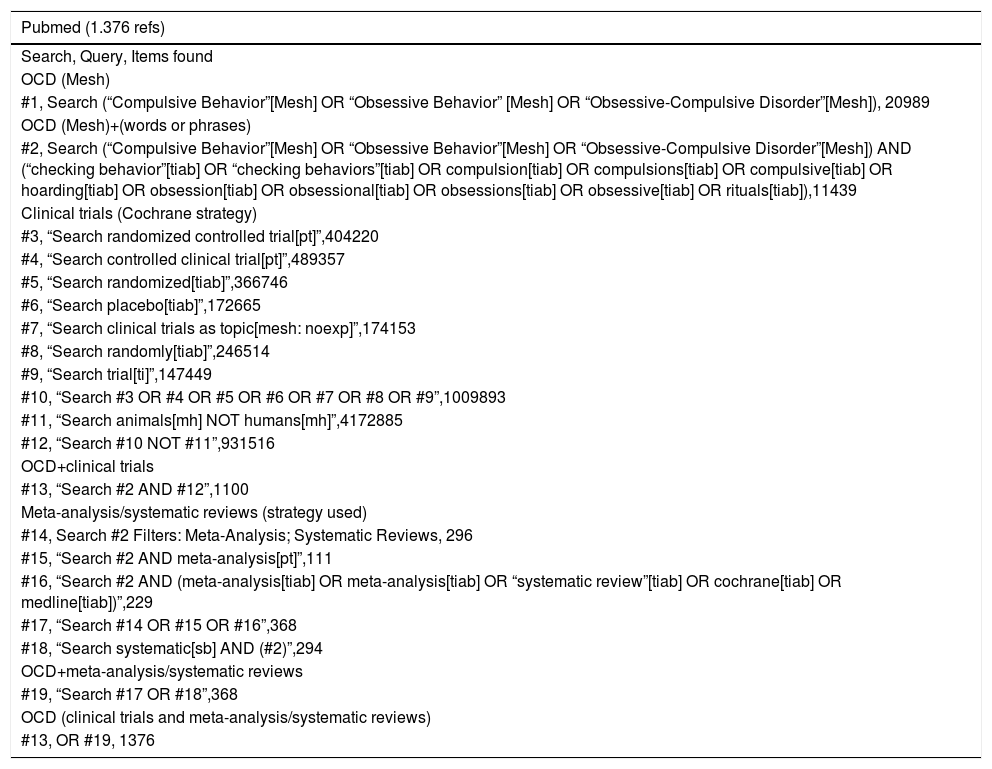

To assess how consistent the recommendation was with current evidence, an initial literature search was conducted in PubMed, PsychInfo and Cochrane Library on randomised clinical trials and systematic reviews of OCD interventions published through February 2016 (with no starting date limit). The search strategy is presented in Table 3 and the search results are available on request.

Search strategy for randomised clinical trials and systematic reviews of studies on interventions for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

| Pubmed (1.376 refs) |

|---|

| Search, Query, Items found |

| OCD (Mesh) |

| #1, Search (“Compulsive Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Obsessive Behavior” [Mesh] OR “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder”[Mesh]), 20989 |

| OCD (Mesh)+(words or phrases) |

| #2, Search (“Compulsive Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Obsessive Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder”[Mesh]) AND (“checking behavior”[tiab] OR “checking behaviors”[tiab] OR compulsion[tiab] OR compulsions[tiab] OR compulsive[tiab] OR hoarding[tiab] OR obsession[tiab] OR obsessional[tiab] OR obsessions[tiab] OR obsessive[tiab] OR rituals[tiab]),11439 |

| Clinical trials (Cochrane strategy) |

| #3, “Search randomized controlled trial[pt]”,404220 |

| #4, “Search controlled clinical trial[pt]”,489357 |

| #5, “Search randomized[tiab]”,366746 |

| #6, “Search placebo[tiab]”,172665 |

| #7, “Search clinical trials as topic[mesh: noexp]”,174153 |

| #8, “Search randomly[tiab]”,246514 |

| #9, “Search trial[ti]”,147449 |

| #10, “Search #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9”,1009893 |

| #11, “Search animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]”,4172885 |

| #12, “Search #10 NOT #11”,931516 |

| OCD+clinical trials |

| #13, “Search #2 AND #12”,1100 |

| Meta-analysis/systematic reviews (strategy used) |

| #14, Search #2 Filters: Meta-Analysis; Systematic Reviews, 296 |

| #15, “Search #2 AND meta-analysis[pt]”,111 |

| #16, “Search #2 AND (meta-analysis[tiab] OR meta-analysis[tiab] OR “systematic review”[tiab] OR cochrane[tiab] OR medline[tiab])”,229 |

| #17, “Search #14 OR #15 OR #16”,368 |

| #18, “Search systematic[sb] AND (#2)”,294 |

| OCD+meta-analysis/systematic reviews |

| #19, “Search #17 OR #18”,368 |

| OCD (clinical trials and meta-analysis/systematic reviews) |

| #13, OR #19, 1376 |

| Psycinfo (947 refs) |

|---|

| OCD (Mesh) |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Obsessive Compulsive Disorder”) 9977 |

| (words or phrases) |

| TI,AB(“checking behavior”) OR TI,AB(“checking behaviors”) OR TI,AB(compulsion) OR TI,AB(compulsions) OR TI,AB(compulsive) OR TI,AB(hoarding) OR TI,AB(obsession) OR TI,AB(obsessional) OR TI,AB(obsessions) OR TI,AB(obsessive) OR TI,AB(rituals) 36603 |

| OCD (Mesh)+(words or phrases) |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Obsessive Compulsive Disorder”) AND (TI,AB(“checking behavior”) OR TI,AB(“checking behaviors”) OR TI,AB(compulsion) OR TI,AB(compulsions) OR TI,AB(compulsive) OR TI,AB(hoarding) OR TI,AB(obsession) OR TI,AB(obsessional) OR TI,AB(obsessions) OR TI,AB(obsessive) OR TI,AB(rituals)) 9754 |

| Clinical trials |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Clinical trials”) 5586 |

| DTYPE(randomized controlled trial) OR DTYPE(controlled clinical trial) OR TI,AB(randomized) OR TI,AB(placebo) OR TI,AB(randomly) OR TI(trial) 136658 |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Clinical trials”) AND DTYPE(randomized controlled trial) OR DTYPE(controlled clinical trial) OR TI,AB(randomized) OR TI,AB(placebo) OR TI,AB(randomly) OR TI(trial) 137729 |

| OCD+clinical trials |

| OCD (9754 refs) AND Clinical trials (137729)=765 |

| Meta-analysis/systematic reviews (strategy used) |

| TI,AB(metaanalysis) OR TI,AB(meta-analysis) OR TI,AB(systematic review) OR TI,AB(cochrane) OR TI,AB(medline) 44556 |

| Toc+meta-analysis/systematic reviews |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Obsessive Compulsive Disorder”) AND (TI,AB(“checking behavior”) OR TI,AB(“checking behaviors”) OR TI,AB(compulsion) OR TI,AB(compulsions) OR TI,AB(compulsive) OR TI,AB(hoarding) OR TI,AB(obsession) OR TI,AB(obsessional) OR TI,AB(obsessions) OR TI,AB(obsessive) OR TI,AB(rituals)) AND (TI,AB(meta-analysis) OR TI,AB(meta-analysis) OR TI,AB(systematic review) OR TI,AB(cochrane) OR TI,AB(medline)) 241 |

| MJSUB.EXACT(“Obsessive Compulsive Disorder”) AND (TI,AB(“checking behavior”) OR TI,AB(“checking behaviors”) OR TI,AB(compulsion) OR TI,AB(compulsions) OR TI,AB(compulsive) OR TI,AB(hoarding) OR TI,AB(obsession) OR TI,AB(obsessional) OR TI,AB(obsessions) OR TI,AB(obsessive) OR TI,AB(rituals)) AND Limits (metaanalysis and revisiones sistematicas) 153 |

| Meta-analysis/RS (two limits) 241 |

| OCD (clinical trials and meta-analysis/systematic reviews) |

| OCD (9754 refs) AND Metaanalysis/systematic reviews (241)=255 |

| Cochrane (686 refs) |

|---|

| OCD (Mesh) |

| Trees 440#1 MeSH descriptor: [Compulsive Behavior] explode all Trees 440 |

| Trees 36#2 MeSH descriptor: [Obsessive Behavior] explode all Trees 36 |

| Trees 725#3 MeSH descriptor: [Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder] explode all Trees 725 |

| #4 (#1 or #2 or #3) 1175 |

| (words or phrases) |

| #5 (checking behavior:ti,ab OR “checking behaviors”:ti,ab OR compulsion:ti,ab OR compulsions:ti,ab OR compulsive:ti,ab OR hoarding:ti,ab OR obsession:ti,ab OR obsessional:ti,ab OR obsessions:ti,ab OR obsessive:ti,ab OR rituals:ti,ab) 1876 |

| OCD (Mesh)+(words or phrases) |

| #6 (#4 and #5) 714 |

| Clinical trials |

| #7 randomized clinical trial:pt 312647 |

| #8 controlled clinical trial:pt 394601 |

| #9 randomized:ti,ab 324787 |

| #10 placebo:ti,ab 163570 |

| #11 randomly:ti,ab 130571 |

| #12 trial:ti 162239 |

| #13 MeSH descriptor: [Clinical Trials as Topic] this term only 34554 |

| #14 (#7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13) 664113 |

| OCD+clinical trials |

| #15 (#6 and #14) 652 |

| Meta-analysis/systematic reviews (strategy used) |

| #16 (metaanalysis or meta-analysis or systematic review*) 60853 |

| Trees 581#17 MeSH descriptor: [Meta-Analysis as Topic] explode all Trees 581 |

| Trees 166#18 MeSH descriptor: [Meta-Analysis] explode all Trees 166 |

| #19 (#16 or #17 or #18) 60853 |

| #20 (#6 and #19) 52 |

| OCD (clinical trials and meta-analysis/systematic reviews) |

| #15 or #20 686 |

Once the new guideline is published, the SEP webpage will post the opinions of the potential target decision makers so their opinions can be considered in future guideline updates.

ResultsScopeTargetsThis consensus is relevant to adults (18 years or older) diagnosed with OCD and to their relatives/caregivers, and to all healthcare professionals providing them with help, treatment or care at the level of specialised mental health care.

SettingSpecialised mental health care.

Actions or interventionsPharmacological treatment, alone or combined with other therapeutic methods, OCD of varying severity and response to prior treatment.

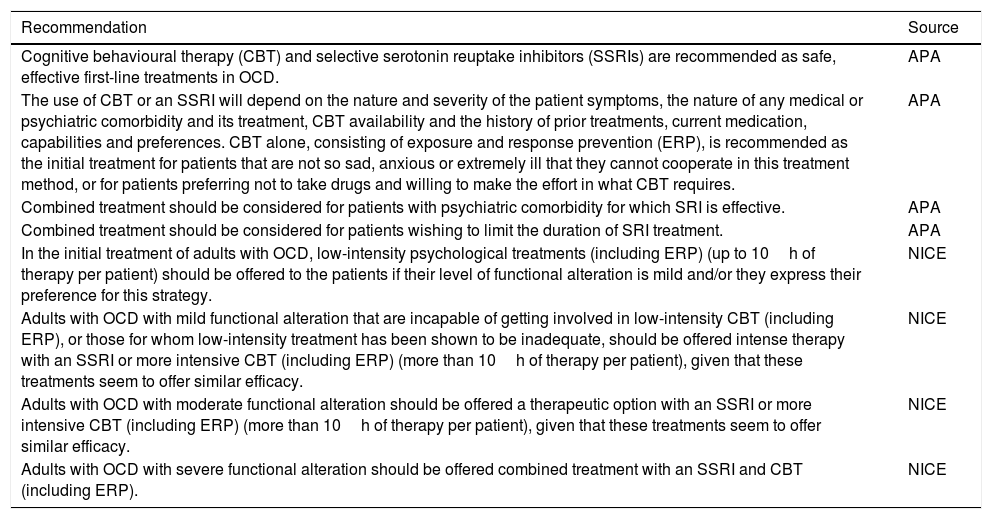

RecommendationsAcute treatmentPsychopharmacological treatment vs psychotherapy vs combined treatment| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended as safe, effective first-line treatments in OCD. | APA |

| The use of CBT or an SSRI will depend on the nature and severity of the patient symptoms, the nature of any medical or psychiatric comorbidity and its treatment, CBT availability and the history of prior treatments, current medication, capabilities and preferences. CBT alone, consisting of exposure and response prevention (ERP), is recommended as the initial treatment for patients that are not so sad, anxious or extremely ill that they cannot cooperate in this treatment method, or for patients preferring not to take drugs and willing to make the effort in what CBT requires. | APA |

| Combined treatment should be considered for patients with psychiatric comorbidity for which SRI is effective. | APA |

| Combined treatment should be considered for patients wishing to limit the duration of SRI treatment. | APA |

| In the initial treatment of adults with OCD, low-intensity psychological treatments (including ERP) (up to 10h of therapy per patient) should be offered to the patients if their level of functional alteration is mild and/or they express their preference for this strategy. | NICE |

| Adults with OCD with mild functional alteration that are incapable of getting involved in low-intensity CBT (including ERP), or those for whom low-intensity treatment has been shown to be inadequate, should be offered intense therapy with an SSRI or more intensive CBT (including ERP) (more than 10h of therapy per patient), given that these treatments seem to offer similar efficacy. | NICE |

| Adults with OCD with moderate functional alteration should be offered a therapeutic option with an SSRI or more intensive CBT (including ERP) (more than 10h of therapy per patient), given that these treatments seem to offer similar efficacy. | NICE |

| Adults with OCD with severe functional alteration should be offered combined treatment with an SSRI and CBT (including ERP). | NICE |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; BAP: British Association of Psychopharmacology; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; ERP: exposure and response prevention; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; SRI: serotonin reuptake inhibitor (including clomipramine and the SSRI); SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

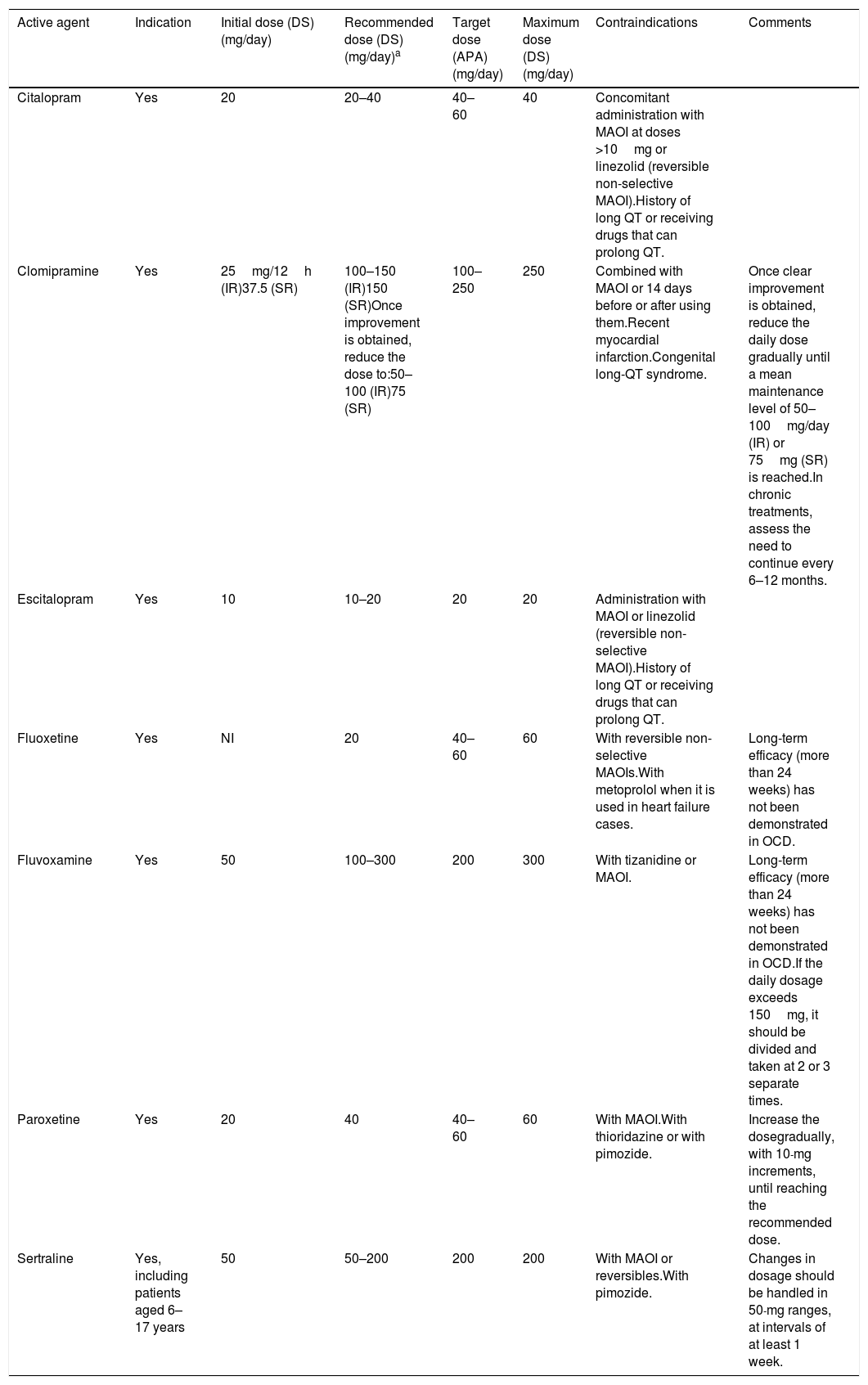

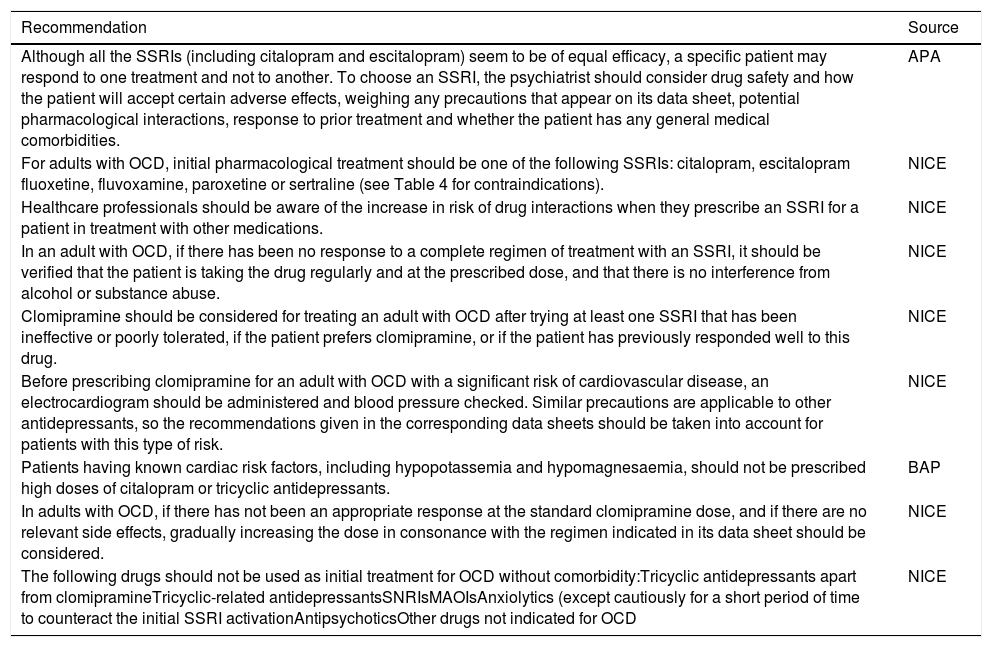

Efficacy, safety and tolerability of psychopharmacological treatmentsAs the APA guideline points out, although some meta-analyses including placebo-controlled clinical trials suggest that clomipramine is more effective than fluvoxamine, fluoxetine and sertraline, the results of the clinical trials that have directly compared clomipramine with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) do not support this view.9,10 Given that SSRIs present milder side effects than clomipramine, an SSRI is preferable as the initial therapeutic option.10 However, relevant adverse effects such as QT prolongation16,17 or hyponatraemia18–20 should be remembered when monitoring patients treated with SSRIs and other new antidepressants. Another point is that various studies have assessed the dose-response relationship for different SSRIs21–25 and, based on the BAP guideline,6 some tests show that high SSRI doses are more effective, although less tolerable. Along these lines, the APA guideline also indicates that greater response and symptom relief are possible using doses exceeding the manufacturer-recommended maximum.9

| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| Although all the SSRIs (including citalopram and escitalopram) seem to be of equal efficacy, a specific patient may respond to one treatment and not to another. To choose an SSRI, the psychiatrist should consider drug safety and how the patient will accept certain adverse effects, weighing any precautions that appear on its data sheet, potential pharmacological interactions, response to prior treatment and whether the patient has any general medical comorbidities. | APA |

| For adults with OCD, initial pharmacological treatment should be one of the following SSRIs: citalopram, escitalopram fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine or sertraline (see Table 4 for contraindications). | NICE |

| Healthcare professionals should be aware of the increase in risk of drug interactions when they prescribe an SSRI for a patient in treatment with other medications. | NICE |

| In an adult with OCD, if there has been no response to a complete regimen of treatment with an SSRI, it should be verified that the patient is taking the drug regularly and at the prescribed dose, and that there is no interference from alcohol or substance abuse. | NICE |

| Clomipramine should be considered for treating an adult with OCD after trying at least one SSRI that has been ineffective or poorly tolerated, if the patient prefers clomipramine, or if the patient has previously responded well to this drug. | NICE |

| Before prescribing clomipramine for an adult with OCD with a significant risk of cardiovascular disease, an electrocardiogram should be administered and blood pressure checked. Similar precautions are applicable to other antidepressants, so the recommendations given in the corresponding data sheets should be taken into account for patients with this type of risk. | NICE |

| Patients having known cardiac risk factors, including hypopotassemia and hypomagnesaemia, should not be prescribed high doses of citalopram or tricyclic antidepressants. | BAP |

| In adults with OCD, if there has not been an appropriate response at the standard clomipramine dose, and if there are no relevant side effects, gradually increasing the dose in consonance with the regimen indicated in its data sheet should be considered. | NICE |

| The following drugs should not be used as initial treatment for OCD without comorbidity:Tricyclic antidepressants apart from clomipramineTricyclic-related antidepressantsSNRIsMAOIsAnxiolytics (except cautiously for a short period of time to counteract the initial SSRI activationAntipsychoticsOther drugs not indicated for OCD | NICE |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; BAP: British Association of Psychopharmacology; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; SNRI: serotonin reuptake inhibitor and norepinephrine; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

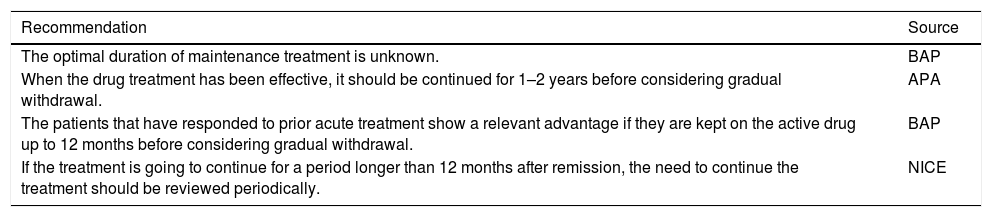

Duration of treatment| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| The optimal duration of maintenance treatment is unknown. | BAP |

| When the drug treatment has been effective, it should be continued for 1–2 years before considering gradual withdrawal. | APA |

| The patients that have responded to prior acute treatment show a relevant advantage if they are kept on the active drug up to 12 months before considering gradual withdrawal. | BAP |

| If the treatment is going to continue for a period longer than 12 months after remission, the need to continue the treatment should be reviewed periodically. | NICE |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; BAP: British Association of Psychopharmacology; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Predictors of response and special symptomsOur literature search found many studies that assessed possible predictors of response to the different pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments in several clinical situations, and a predictive model of response to pharmacological treatment was even proposed.26 However, the evidence is insufficient for making a recommendation. Specifically, the APA guideline indicates that “there are no demographic or clinical variables that constitute sufficiently precise predictors of the treatment result to allow their use in drug selection”.10 As other authors have generally indicated, “having a single marker available or predicting the response in the different psychiatric entities is not expected.”27

Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with partial or lack of response to treatmentThe recommendations that follow refer to the failure of a first treatment regimen. There are no specific recommendations when the patient has not responded to 2 treatment regimens.

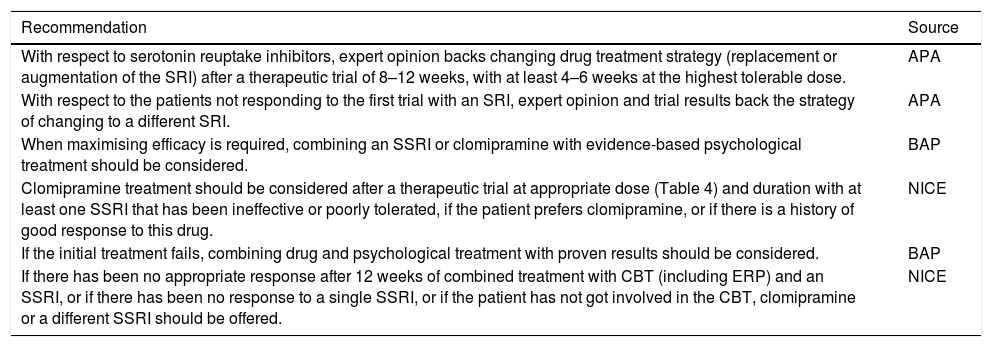

Treatment optimisation or substitution| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| With respect to serotonin reuptake inhibitors, expert opinion backs changing drug treatment strategy (replacement or augmentation of the SRI) after a therapeutic trial of 8–12 weeks, with at least 4–6 weeks at the highest tolerable dose. | APA |

| With respect to the patients not responding to the first trial with an SRI, expert opinion and trial results back the strategy of changing to a different SRI. | APA |

| When maximising efficacy is required, combining an SSRI or clomipramine with evidence-based psychological treatment should be considered. | BAP |

| Clomipramine treatment should be considered after a therapeutic trial at appropriate dose (Table 4) and duration with at least one SSRI that has been ineffective or poorly tolerated, if the patient prefers clomipramine, or if there is a history of good response to this drug. | NICE |

| If the initial treatment fails, combining drug and psychological treatment with proven results should be considered. | BAP |

| If there has been no appropriate response after 12 weeks of combined treatment with CBT (including ERP) and an SSRI, or if there has been no response to a single SSRI, or if the patient has not got involved in the CBT, clomipramine or a different SSRI should be offered. | NICE |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; BAP: British Association of Psychopharmacology; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; ERP: exposure and response prevention; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SRI: serotonin reuptake inhibitor (including clomipramine and the SSRIs); SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

In addition to the previous recommendations about treatment optimisation strategies, it should be remembered that some patients not responding to initial treatment with an SRI may simply respond after a longer period of continued treatment with the same drug.9,10 Some guidelines also point out that, for some patients (such as those having only a slight response to prior treatments and tolerating the drug well) using higher doses than those recommended in the data sheet (Table 4) may be beneficial; however, individual circumstances have to be taken into account to do so.9,10

Antidepressant dosage and contraindications in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

| Active agent | Indication | Initial dose (DS) (mg/day) | Recommended dose (DS) (mg/day)a | Target dose (APA) (mg/day) | Maximum dose (DS) (mg/day) | Contraindications | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | Yes | 20 | 20–40 | 40–60 | 40 | Concomitant administration with MAOI at doses >10mg or linezolid (reversible non-selective MAOI).History of long QT or receiving drugs that can prolong QT. | |

| Clomipramine | Yes | 25mg/12h (IR)37.5 (SR) | 100–150 (IR)150 (SR)Once improvement is obtained, reduce the dose to:50–100 (IR)75 (SR) | 100–250 | 250 | Combined with MAOI or 14 days before or after using them.Recent myocardial infarction.Congenital long-QT syndrome. | Once clear improvement is obtained, reduce the daily dose gradually until a mean maintenance level of 50–100mg/day (IR) or 75mg (SR) is reached.In chronic treatments, assess the need to continue every 6–12 months. |

| Escitalopram | Yes | 10 | 10–20 | 20 | 20 | Administration with MAOI or linezolid (reversible non-selective MAOI).History of long QT or receiving drugs that can prolong QT. | |

| Fluoxetine | Yes | NI | 20 | 40–60 | 60 | With reversible non-selective MAOIs.With metoprolol when it is used in heart failure cases. | Long-term efficacy (more than 24 weeks) has not been demonstrated in OCD. |

| Fluvoxamine | Yes | 50 | 100–300 | 200 | 300 | With tizanidine or MAOI. | Long-term efficacy (more than 24 weeks) has not been demonstrated in OCD.If the daily dosage exceeds 150mg, it should be divided and taken at 2 or 3 separate times. |

| Paroxetine | Yes | 20 | 40 | 40–60 | 60 | With MAOI.With thioridazine or with pimozide. | Increase the dosegradually, with 10-mg increments, until reaching the recommended dose. |

| Sertraline | Yes, including patients aged 6–17 years | 50 | 50–200 | 200 | 200 | With MAOI or reversibles.With pimozide. | Changes in dosage should be handled in 50-mg ranges, at intervals of at least 1 week. |

APA: American Psychiatric Association; DS: data sheet; IR: immediate release; MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NI: not indicated; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; SR: sustained release.

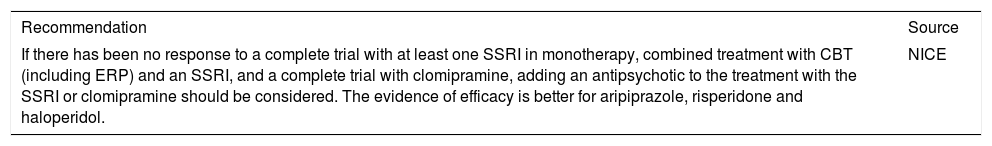

| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| If there has been no response to a complete trial with at least one SSRI in monotherapy, combined treatment with CBT (including ERP) and an SSRI, and a complete trial with clomipramine, adding an antipsychotic to the treatment with the SSRI or clomipramine should be considered. The evidence of efficacy is better for aripiprazole, risperidone and haloperidol. | NICE |

CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; ERP: exposure and response prevention; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Other therapeutic optionsThe guidelines consulted indicated that other therapeutic options had been assessed, but that these lacked enough evidence to recommend their general use. However, using these options should be considered when the recommended therapeutic options have failed, after evaluating the specific circumstances of each case. The following are found among these options:

- •

The combination of clomipramine with an SSRI, with or without CBT.

- •

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, pregabalin and topiramate.

- •

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressants (venlafaxine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) (phenelzine, tranylcypromine) or mirtazapine.

- •

Glutamatergic drugs such as N-acetylcysteine, memantine, riluzole, glycine and intravenous (i.v.) ketamine.

- •

The use of i.v. clomipramine in patients not responding to oral clomipramine.

- •

Stimulants such as d-amphetamine.

- •

Other drugs such as ondansetron, granisetron, pindolol, celecoxib, morphine and tramadol.

- •

Deep brain stimulation of specific brain targets (for example, nucleus accumbens or subthalamic nucleus) is a physical treatment that can be considered in patients with OCD that have been resistant to multiple drug trials and to CBT. Each case has to be evaluated individually, weighing the risk-benefit value of the intervention carefully.

- •

Neurosurgery (e.g., cingulotomy) can be considered in patients with OCD that have been resistant to multiple drug trials and to CBT. Each case has to be evaluated individually, weighing the risk-benefit value of the intervention carefully, because the possible adverse effects are often irreversible.

There is no evidence that makes it possible to give any specific recommendations for treating OCD in the elderly. However, the experience with psychopharmacological treatment in other psychiatric areas allows suggesting that treatment should be initiated at the lowest dose and increased more gradually than with young adults.10,14 Possible renal function alteration and its implication in dose regimens should be taken into account in handling psychopharmacological treatment of these patients. It is also important to consider that other drugs are often used for treating concomitant diseases in these patients and, consequently, drug interactions may exist.10,14

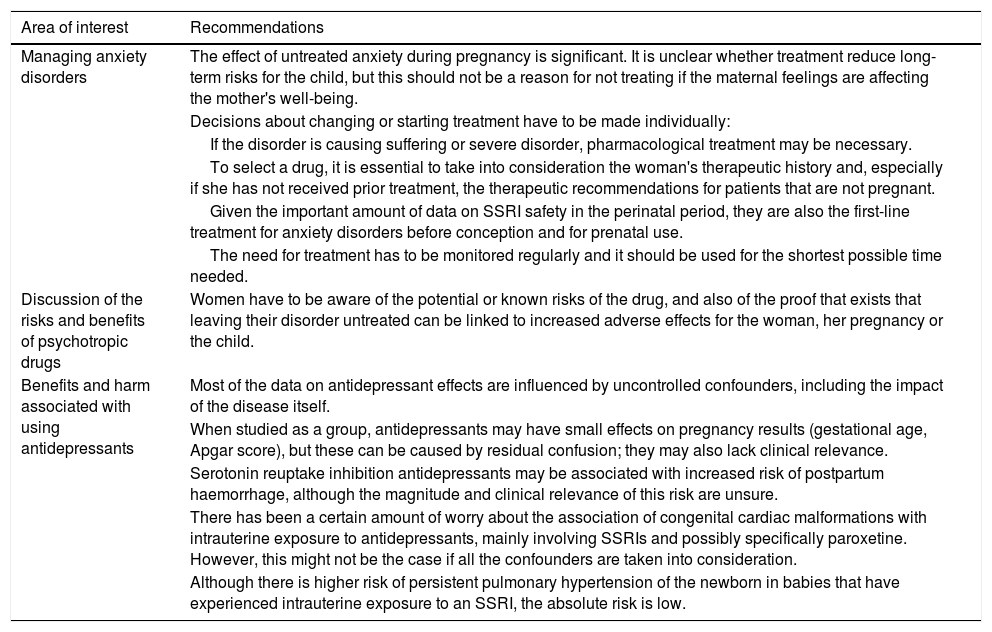

Pregnant and breast-feeding womenThe APA guideline states that “deciding to initiate or interrupt psychopharmacological treatment during pregnancy or breast-feeding makes it necessary to assess the risk-benefit relationship, but without having complete information available.”10 As the Canadian guideline indicates, such assessment has to take the risk of no treatment into account.14 Consequently, it is impossible to give any specific recommendations about this matter.

The British Association for Psychopharmacology has recently published a consensus guideline on the management of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy and the postpartum period.28Table 5Table 5 summarises the recommendations from this guideline that we have considered the most noteworthy in relationship to anxiety disorders, emphasising the comments about antidepressants, because these are the first-line drugs in treating OCD.

British Association for Psychopharmacology recommendations for the treatment of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

| Area of interest | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Managing anxiety disorders | The effect of untreated anxiety during pregnancy is significant. It is unclear whether treatment reduce long-term risks for the child, but this should not be a reason for not treating if the maternal feelings are affecting the mother's well-being. |

| Decisions about changing or starting treatment have to be made individually: | |

| If the disorder is causing suffering or severe disorder, pharmacological treatment may be necessary. | |

| To select a drug, it is essential to take into consideration the woman's therapeutic history and, especially if she has not received prior treatment, the therapeutic recommendations for patients that are not pregnant. | |

| Given the important amount of data on SSRI safety in the perinatal period, they are also the first-line treatment for anxiety disorders before conception and for prenatal use. | |

| The need for treatment has to be monitored regularly and it should be used for the shortest possible time needed. | |

| Discussion of the risks and benefits of psychotropic drugs | Women have to be aware of the potential or known risks of the drug, and also of the proof that exists that leaving their disorder untreated can be linked to increased adverse effects for the woman, her pregnancy or the child. |

| Benefits and harm associated with using antidepressants | Most of the data on antidepressant effects are influenced by uncontrolled confounders, including the impact of the disease itself. |

| When studied as a group, antidepressants may have small effects on pregnancy results (gestational age, Apgar score), but these can be caused by residual confusion; they may also lack clinical relevance. | |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibition antidepressants may be associated with increased risk of postpartum haemorrhage, although the magnitude and clinical relevance of this risk are unsure. | |

| There has been a certain amount of worry about the association of congenital cardiac malformations with intrauterine exposure to antidepressants, mainly involving SSRIs and possibly specifically paroxetine. However, this might not be the case if all the confounders are taken into consideration. | |

| Although there is higher risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in babies that have experienced intrauterine exposure to an SSRI, the absolute risk is low. |

Source: Based on McAllister-Williams et al.28

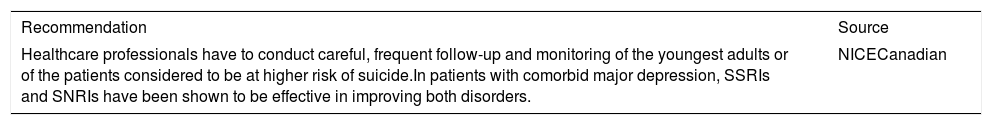

| Recommendation | Source |

|---|---|

| Healthcare professionals have to conduct careful, frequent follow-up and monitoring of the youngest adults or of the patients considered to be at higher risk of suicide.In patients with comorbid major depression, SSRIs and SNRIs have been shown to be effective in improving both disorders. | NICECanadian |

NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SNRI: serotonin reuptake inhibitor and norepinephrine; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

DiscussionThe guideline of recommendations for pharmacological treatment of OCD in adults that we have developed constitutes the first guideline prepared in Spain with this goal. However, this guideline has some limitations, which are detailed below.

The guideline is based on recommendations from other guidelines developed in other settings, mainly in Anglo-Saxon countries. During the assessment of the guidelines, we considered their applicability to be low (except for that published by the NICE). It should be noted that one of the objectives of our expert group involved in developing these guidelines was to include recommendations that were applicable to our setting. This group felt that the thoroughness of one of the guidelines chosen to be assessed—the Canadian—was low; it is consequently unsurprising that only one recommendation from that guideline has been included.

Our guideline does not cover various aspects relevant to managing OCD, particularly psychotherapy, other than in what concerns choosing the initial treatment; several initiatives about psychotherapeutic guidelines have been put into effect in our setting.29 There are other treatment aspects (such as the use of physical therapies) about which evidence confirming their usefulness is growing,30–32 which are not treated in depth in this document. Reviewing such OCD treatment elements has not been one of our objectives, but the specialist in managing this disorder should consider them.

Throughout the discussion of recommendations, it has also become clear that there are many features of pharmacological OCD management on which evidence is very limited, making it impossible to provide any specific recommendation. Examples of these aspects are personalising treatment by using predictive factors, using drugs in special populations such as the elderly, and managing OCD during pregnancy.

Lastly, it should be emphasised that the potential benefits of a clinical practice guideline depend on its quality, dissemination and application.33,34 Dissemination is planned through non-restricted access once it is published and diffusion by SEP among its members. However, guideline application activities are still undeveloped and the results of that application have yet to be assessed.

ConclusionsDespite the limitations mentioned, we hope that this guideline will be useful for psychiatrists working in Spain and will, as it was the initial objective, improve the management of the disorder in our setting and help to reduce the disease burden for the patient.

FundingThe preparation of this guideline has been sponsored and funded by the Spanish Society of Psychiatry (Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría).

Conflict of interestsDr Menchón has received research grants from the Medtronic institution AB Biotics; travel grants from Servier and fees from Janssen as a speaker. Dr Bobes has received research grants and has been a consultant, advisor or speaker in the last 5 years for AB-Biotics, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Angelini, Casen Recordati, D&A Pharma, Exeltis, Gilead, GSK, Ferrer, Indivior, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Mundipharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Reckitt-Benckiser, Roche, Servier, Shire and Schwabe Farma Ibérica; has obtained research funding from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Centre for Biomedical Research Network in the area of Mental Health [CIBERSAM is the Spanish acronym] and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III), the Spanish Ministry of Healthcare, Social Services and Equality-National Drug Plan and the 7th European Union Framework Programme. Dr Álamo has been an honorary speaker for Adamed, Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Exeltis, Ferrer, Fuinsa, Grunenthal Indivior, Janssen-Cilag, Juste SAQF, Kyowa Kiry, Lundbeck, Mudipharma, Normon, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Rovi, Rubió, Servier and Shire; an honorary consultant for Angelini, Casen-Recordati, Janssen-Cilag and Kyowa Kiry Mudipharma Normon. Dr García-Portilla is a member of the of the Angeline Advisory Committee, the European Medicines Agency and Janssen-Cilag; has received research grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Janssen-Cilag and Lundbeck; has participated in presentations for Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Pfizer. Dr Ibáñez has received grants and has been a speaker or an advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceutical SA and Servier. Dr Bousoño has been an honorary speaker for Lundbeck, Servier, Exeltis, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Otsuka; and has received travel grants from Lundbeck, Servier, Exeltis, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and Otsuka. Dr Saiz-González has participated as an expert or has given a conference for Otsuka, Janssen and Pfizer. Dr Saiz-Ruiz has participated as an expert or has given a conference for Adamed, Lundbeck, Servile, Neurofarmagen, Otsuka, Indivior, Schwabe and Janssen; and has received research funding from public agencies (CIBERSAM; FIS; CAM; Universidad de Alcalá), Fundación Canis Majoris, Lundbeck, Janssen, Medtronic and Ferrer.

The authors thank Fernando Rico-Villademoros (COCIENTE S.L., Madrid) for his methodological advice throughout the entire project, as well as for his editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript. This collaboration has been funded by the SEP.

Please cite this article as: Menchon JM, Bobes J, Alamo C, Alonso P, García-Portilla MP, Ibáñez Á, et al. Tratamiento farmacológico del trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo en adultos: una guía de práctica clínica basada en el método ADAPTE. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019;12:77–91.