There has been an increase in the prescription of antidepressants (AD) in primary care (PC). However, it is unclear whether this was explained by a rise in diagnoses with an indication for AD. We investigated the changes in frequency and the variables associated with AD prescription in Catalonia, Spain.

MethodsWe retrieved AD prescription, sociodemographic, and health-related data using individual electronic health records from a population-representative sample (N=947.698) attending PC between 2010 and 2019. Prescription of AD was calculated using DHD (Defined Daily Doses per 1000 inhabitants/day). We compared cumulative changes in DHD with cumulative changes in diagnoses with an indication for AD during the study period. We used Poisson regression to examine sociodemographic and health-related variables associated with AD prescription.

ResultsBoth AD prescription and mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD gradually increased. At the end of the study period, DHD of AD prescriptions and mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD reached cumulative increases of 404% and 49% respectively. Female sex (incidence rate ratio (IRR)=2.83), older age (IRR=25.43), and lower socio-economic status (IRR=1.35) were significantly associated with increased risk of being prescribed an AD.

ConclusionsOur results from a large and representative cohort of patients confirm a steady increase of AD prescriptions that is not explained by a parallel increase in mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD. A trend on AD off-label and over-prescriptions in the PC system in Catalonia can be inferred from this dissociation.

Antidepressants (AD) are one of the most prescribed pharmacological treatments in developed countries. AD efficacy is well-proven in anxiety, depressive and other mental disorders, but their use is also common in individuals without psychiatric health conditions.1,2 Indeed, recent evidence reported an increase in AD prescription over the latest years.3–12 Concern has been raised on the overuse of AD in several countries, and societal policies and national guidelines have been developed to regulate their use in the general population.13

Several factor might be used to explain this increase, including the more safety profile of new AD classes (i.e. SSRI, or vortioxetine) compared to old AD, a possible overall increase in the incidence of depressive and anxiety disorders,14 or their inappropriate prescription in mild conditions which could be managed without pharmacological treatment as first-step option in primary care (PC).15 Also, it should be noted that a high percentage of patients that starts an AD, usually continue the treatment in the long term, thus further increasing AD's prescription rates.7,16 In addition, it must be mentioned that the lack of consistent and clear agreements on how the biomedical evidence is summarized and applied in the diagnostic process and treatment guidelines of mental disorders might have also play a general role in these circumstances.17

Notably, this surge in AD prescriptions rates has been reported among patients at specialized psychiatric care as well as PC.1,12,18 General practitioners (GP) play a fundamental role within health care systems and in PC settings, since they have usually the first contact with patients. However, most health care systems fail to meet the care demand and available number of GPs, which derives in a significant increase of the workload for these physicians.19

Beyond the economic costs for the healthcare system, there are several potential health consequences for patients that should be considered when an AD is prescribed without a proper indication. Indeed, in spite of their good safety profile, they are not exempt from side effects. About 80% of patients report at least one side effect with the chronic use of AD while about 50% experience more than one, which usually become more frequent over time and are often underestimated by physicians.20 Most common side effects are sexual dysfunction, weight gain, dry mouth, nausea, sleep disturbance and sweating among others more serious adverse effects such as serotonin syndrome and liver toxicity.21,22 However, the highest concern comes from potentially severe adverse events and life-threating risks specially in the elderly population such as falls, seizures, gastrointestinal bleeds, stroke and Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH).23 Those are infrequent, but still present especially if AD are prescribed to a considerable amount of population. Moreover, some patients with depressive episodes receiving an antidepressant may present hypomanic or manic episodes. Therefore, when prescribing an AD, it is fundamental to assess the risks and benefits and also to perform a proper clinical evaluation, since AD might ‘unmask’ bipolar disorders.24

There is a lack of studies in the Spanish territory exploring AD prescription patterns in PC settings, as well as the factors associated. Furthermore, in international studies, the relation between AD prescription with mental health diagnoses and other factors involved has not always been considered. Thus, it is crucial to explore AD prescription patterns in relation to mental health diagnoses and to identify the most relevant factors involved in PC health systems. Understanding the variables influencing AD prescription would allow designing strategies and guidelines to make appropriate use of this pharmacological group in PC. As part of the PRESTO project (www.prestoclinic.cat),25 here we investigated the changes in frequency and the variables associated with AD prescription in a population-representative sample of people attending PC between 2010 and 2019 in Catalonia, Spain.

MethodsAnonymized and unidentified data for this study was extracted by Data Analytics Program for Health Research and Innovation (PADRIS) of the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS), in accordance with the legal and regulatory framework, the ethical principles and transparency. PADRIS periodically accesses detailed individual-level information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, and in-depth health-related and service-use data generated resulting from consultations of patients to the public Catalan healthcare system (CatSalut). CatSalut provides universal public health coverage to all residents from Catalonia, Spain.26

A total of 947,968 patients who attended PC between 2015 and 2019 and did not have any contact with public mental health services in the same period were included in our study. This sample constitutes the control group enrolled in the PRESTO project,25 matched by age, sex, and health-region (corresponding to PC centres distribution) with a sample of 479,000 individuals who consulted the public specialized mental health services of CatSalut during the same time period. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic information, diagnoses, and psychotropic drug prescriptions of these individuals were retrospectively collected from January 2010 to December 2019 by using electronic health records (EHR).

For this specific study, only data from the control cohort (n=947,698) were considered. Prescription of AD was calculated using DHD (Defined Daily Doses per 1000 inhabitants/day). Mental health diagnoses were performed and registered in EHR by the GPs according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-10-MC).

We conducted descriptive analyses to detail the sociodemographic characteristics as well as the specific AD prescribed and mental health diagnoses registered during the study period. Mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD included Mood disorders (F30-39), Neurotic, Stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F40-48), and Eating disorders (F50). We compared cumulative changes in DHD with cumulative changes in diagnoses with an indication for AD during the study period. To determine if the variations in AD prescription were due to continuation of treatment, we analyzed the percentage of individuals in the cohort with at least one AD prescription for each given year. Finally, we used Poisson regression to examine sociodemographic and health-related variables associated with AD prescription. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 28.0 was used for data processing and analyses (IBM Corp; Armonk, NY).

The research has been approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees (CEIC) of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (HCB/2020/0735).

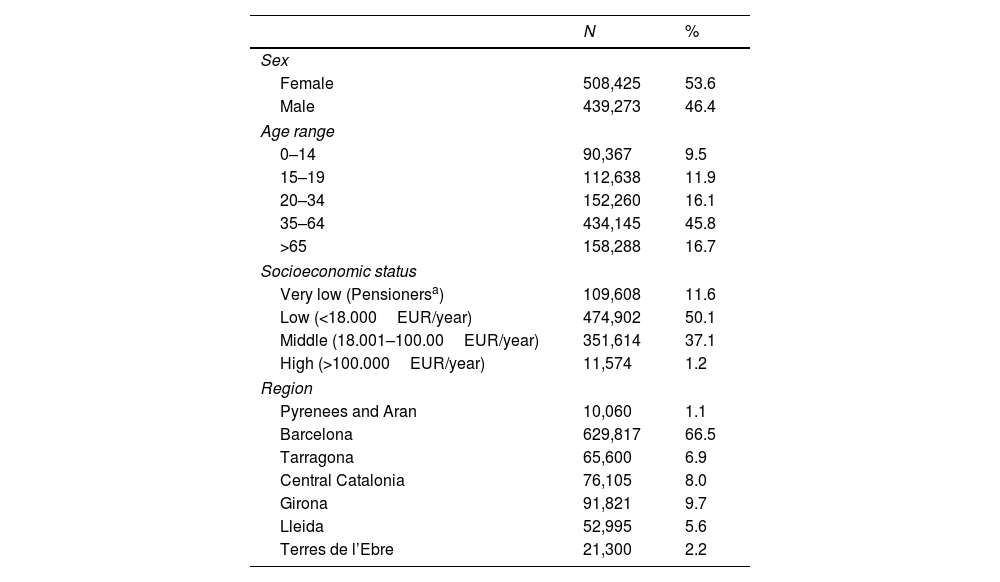

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics of the cohort are detailed in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the cohort (N=947,698).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 508,425 | 53.6 |

| Male | 439,273 | 46.4 |

| Age range | ||

| 0–14 | 90,367 | 9.5 |

| 15–19 | 112,638 | 11.9 |

| 20–34 | 152,260 | 16.1 |

| 35–64 | 434,145 | 45.8 |

| >65 | 158,288 | 16.7 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Very low (Pensionersa) | 109,608 | 11.6 |

| Low (<18.000EUR/year) | 474,902 | 50.1 |

| Middle (18.001–100.00EUR/year) | 351,614 | 37.1 |

| High (>100.000EUR/year) | 11,574 | 1.2 |

| Region | ||

| Pyrenees and Aran | 10,060 | 1.1 |

| Barcelona | 629,817 | 66.5 |

| Tarragona | 65,600 | 6.9 |

| Central Catalonia | 76,105 | 8.0 |

| Girona | 91,821 | 9.7 |

| Lleida | 52,995 | 5.6 |

| Terres de l’Ebre | 21,300 | 2.2 |

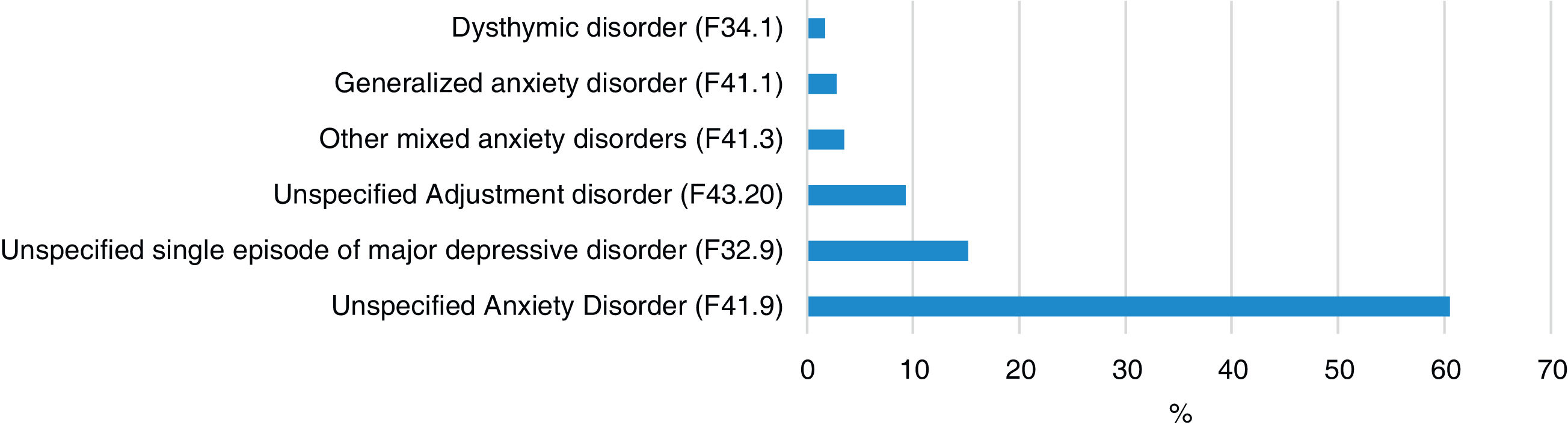

During the study period (2010–2019), 23.6% (223,107) individuals were diagnosed with a mental health condition by GPs, of which 50.2% (111,956) were diagnoses with an indication for AD. Mental health diagnoses with indication for AD are detailed in Fig. 1. The most frequent mental health diagnosis with indication for AD was Unspecified Anxiety Disorder (F41.9) (60.5%).

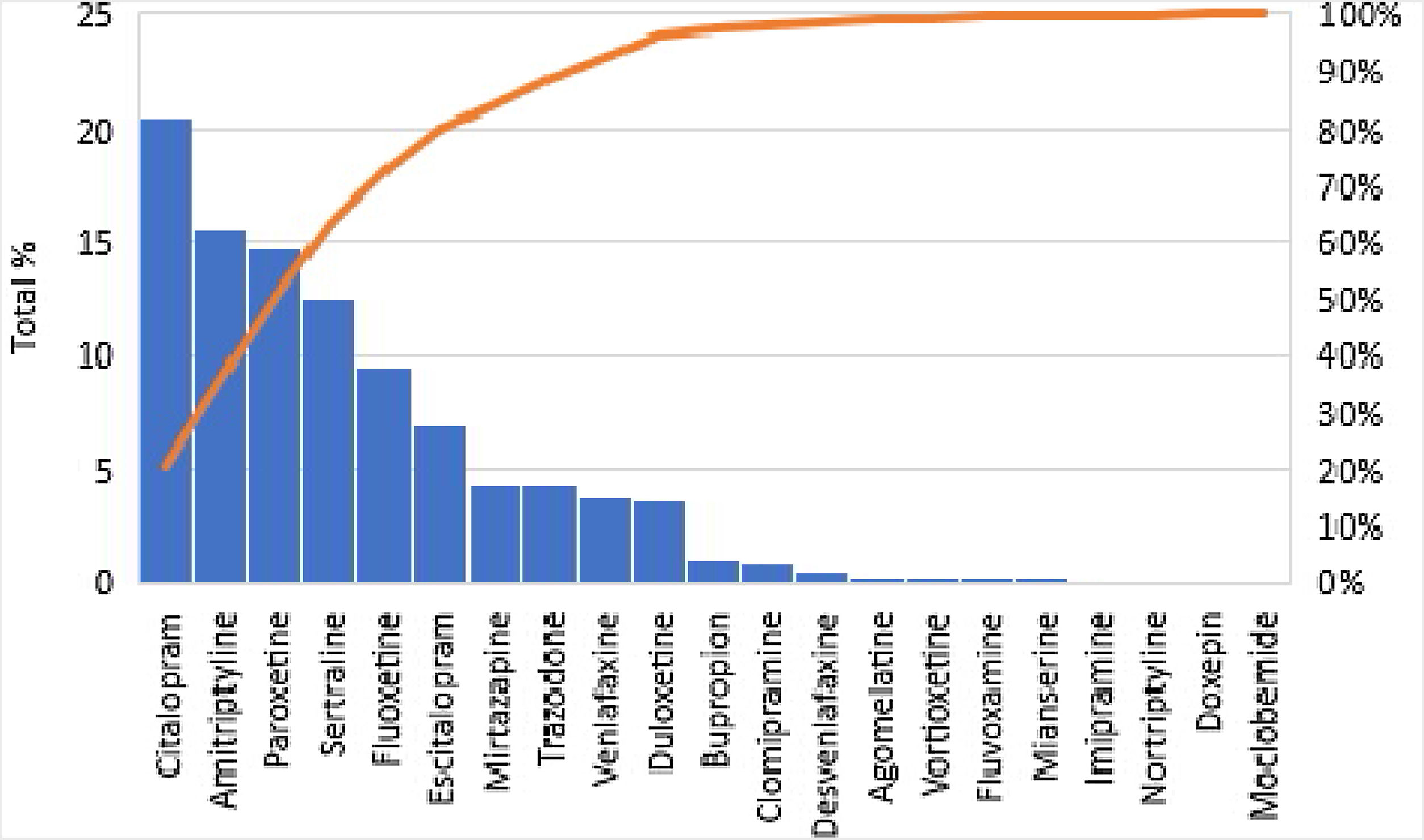

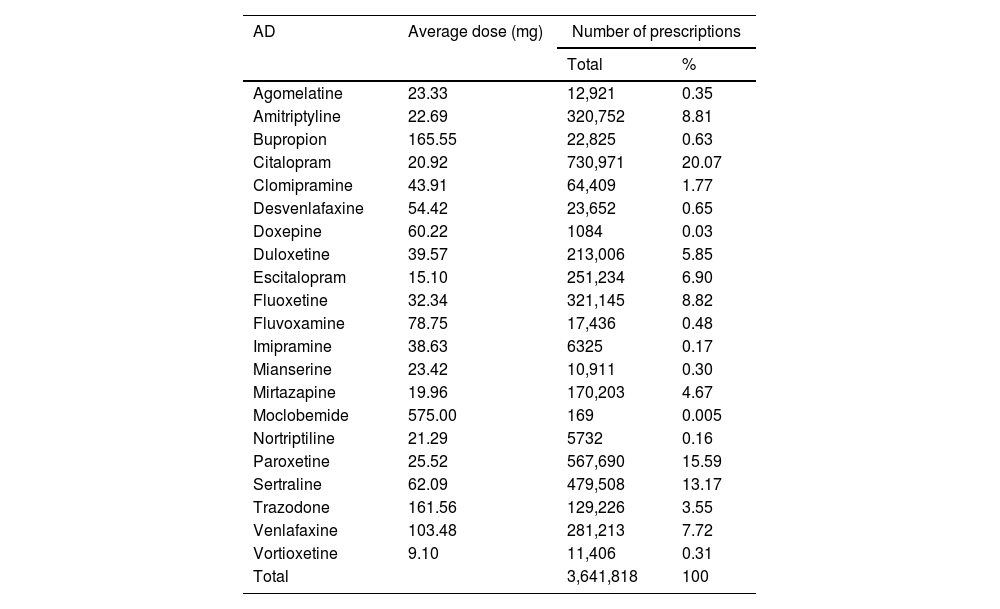

AD prescriptions frequency are detailed in Fig. 2. Citalopram (20.5%) was the most frequent antidepressant prescribed, followed by amitriptyline (15.6%). Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNIR) were prescribed more infrequently with venlafaxine and duloxetine, totalizing 3.8% and 3.7% of the AD prescriptions respectively. Table 2 offers a more detailed description of the average dose for each AD and the total number of prescriptions during the study period.

Average dose for each AD and Total number of prescriptions between 2010 and 2019.

| AD | Average dose (mg) | Number of prescriptions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | ||

| Agomelatine | 23.33 | 12,921 | 0.35 |

| Amitriptyline | 22.69 | 320,752 | 8.81 |

| Bupropion | 165.55 | 22,825 | 0.63 |

| Citalopram | 20.92 | 730,971 | 20.07 |

| Clomipramine | 43.91 | 64,409 | 1.77 |

| Desvenlafaxine | 54.42 | 23,652 | 0.65 |

| Doxepine | 60.22 | 1084 | 0.03 |

| Duloxetine | 39.57 | 213,006 | 5.85 |

| Escitalopram | 15.10 | 251,234 | 6.90 |

| Fluoxetine | 32.34 | 321,145 | 8.82 |

| Fluvoxamine | 78.75 | 17,436 | 0.48 |

| Imipramine | 38.63 | 6325 | 0.17 |

| Mianserine | 23.42 | 10,911 | 0.30 |

| Mirtazapine | 19.96 | 170,203 | 4.67 |

| Moclobemide | 575.00 | 169 | 0.005 |

| Nortriptiline | 21.29 | 5732 | 0.16 |

| Paroxetine | 25.52 | 567,690 | 15.59 |

| Sertraline | 62.09 | 479,508 | 13.17 |

| Trazodone | 161.56 | 129,226 | 3.55 |

| Venlafaxine | 103.48 | 281,213 | 7.72 |

| Vortioxetine | 9.10 | 11,406 | 0.31 |

| Total | 3,641,818 | 100 | |

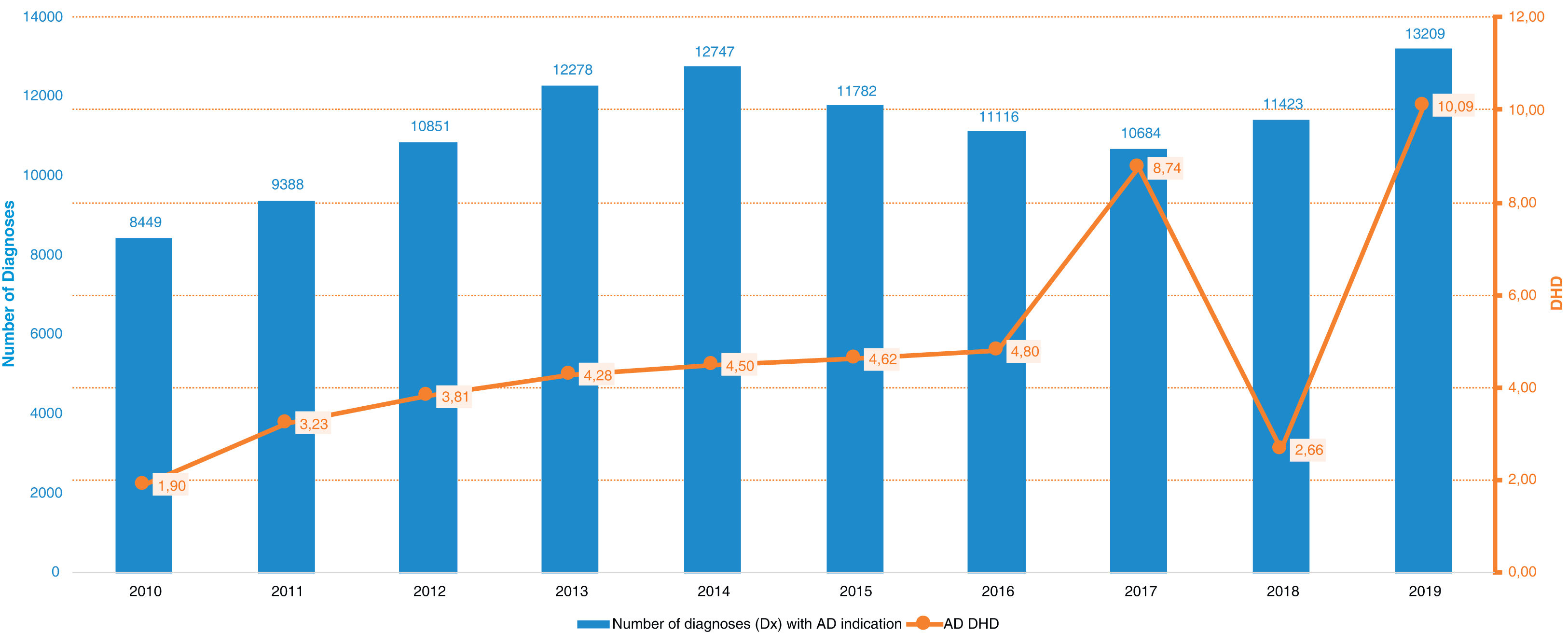

The yearly variations in the number of mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD in relation to DHD for AD prescriptions are shown in Fig. 3. During the study period, the cumulative percentage of diagnoses with an AD indication increased 49% while the AD prescriptions surged to 404%. Similarly, the percentage of individuals in the cohort with at least one AD prescription for each given year were 2.6% in 2010 with a constant rise reaching 6.6% individuals with at least one AD prescription in 2019.

The Poisson regression model showed that the following variables were significantly associated with an increased incidence rate ratio (IRR) of being prescribed an AD: female sex (IRR=2.83; IC=2.82–2.84), older age (IRR=25.44; IC=3.58–120.57), and a lower socio-economic status (IRR=1.35; IC=1.33–1.36).

DiscussionThe results of this study confirm an increase in both AD prescriptions and mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD between 2010 and 2019 in the PC system in Catalonia, Spain. Considering that the cohort studied includes more than 12% of the Catalan population, and is representative of the Catalan population proportionally according to each health-region, socioeconomic status, and sex, these results could be generalizable to the whole population in Catalonia and can be potentially extrapolated to other regions in Spain and international countries with similar characteristics. Noteworthy, while the mental health diagnoses with an AD indication presented a gradual steady increase until reaching a cumulative percentage of 49%, AD prescriptions continued to rise to a higher peak, with a cumulative 404% increase at the end of the study period. This dissociation suggests that there is a trend on AD off-label and over prescriptions in the PC system in Catalonia.

This trend is consistent with what has been previously reported in literature across several PC systems around the world. For instance, studies conducted in the Netherlands,7 Italy,3 UK10 and the United States8 during the last 20 years, using diverse metrics have repeatedly reported at a constant and steady increase in the prescription of AD, especially in PC settings across all age groups.6,9,10,12,18

In line with what we have found, several of the aforementioned studies have reported that the population with the older age ranges presented a higher prevalence of AD use, even when having a greater risk of having adverse effects.23,27 In fact, amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant with higher risk for severe adverse effects in older population, was the second most frequent AD prescribed in our cohort. This is again in line with similar recent studies on AD prescriptions trends in other countries.28–30

Likewise, several studies have also showed that the population that receives the most psychotropics are predominantly female.31,32 Even though this might be related to the higher prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women, other factors could be implicated suggesting on one hand an overtreatment in women and on the other an undertreatment in men. For instance, a large study in Sweden have shown that women have two times more possibilities than men to use ADs when not currently depressed. Among the factors implicated are the different presentation and timing of requesting help for mental issues alongside differences in treatment response and tolerance to diverse classes of ADs. Despite the extensive research on these gender differences, findings have not been reflected in guidelines so far.33

Furthermore, lower socioeconomic status was also associated with increased AD prescription in our results, as well as in other studies. This can be expected, since the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in these populations are in general higher.34,35 It should be noted that older people are usually poly-medicated, thus increasing the risk of pharmacological interactions with AD. Moreover, older people are usually pensioners, bearing lower socioeconomic status. Those are factors for restricted access to psychosocial resources, including psychological therapies, which may avoid the overuse of AD.

Despite its many contributing factors, the constant prescription increase of AD in PC remains a multifactorial problem, which has to do with the prescribing physician, healthcare systems’ resources and the individual who arrives at the PC consultation.36 In this scenario, it is relevant to remember the scarce therapeutic resources available in most PC settings to meet growing demands. Among them is the duration of appointments averaging 10min of duration with obvious consequences for the appropriate assessment, diagnosis and treatment. As consequence, there is usually an imbalance between their caseload, time and resources available, such as psychological services37–39 or mental health specialists to promptly refer severe cases and to provide a timely intervention. Among other reasons, these factors have been suggested as potential reasons for the over prescription of AD without a proper indication.40,41 The increase in the mental health resources available in PC would likely prevent the increase in the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms and avoid their chronification.

To add up to this complex situation, despite established guidelines on when to discontinue AD, their adherence by physicians and patients is frequently inconsistent and are also challenging due to patient's fears of a relapse. In addition, despite AD's long-term potential side-effects, there is emergent evidence about the high relapse risk of discontinuing ADs once started which makes even harder the decision and initiative of GPs and patients’ concerns of suffering from withdrawal symptoms.42,43 Owing to these factors, accumulating evidence indicate that the longer patients are on AD the more difficult is to stop them while GPs are also less inclined to re-assess the possibility of discontinuing them. In contrast, according to a study in UK, more than 50% of the patients do not have an indication to continue AD use after the recommended duration of treatment.44,13 Since long-term prescription of AD is rather the norm than the exception and it has been suggested as another if not the main reason for the steady rise in AD prescription over the last decade.13 Yet, in our results, continuation of treatment did not seem to be the only factor incrementing AD prescriptions as the percentage of individuals in the cohort with an AD prescription increased 4% denoting a three-fold increase (from 2.6% to 6.6%) during the 9 years study period. The chronicity of most prevalent disorders in PC might also play a role in the fact that patients remain far too long on AD as an important percentage of them never reach remission.45

There are also intricate societal and individual factors as well as expectations that might explain this surge in AD prescriptions over the last decades. Among them the decreased population's threshold of tolerance and management of emotional distress caused by the adverse life events (such as grief or job loss), which indirectly gives rise to a “medicalization” of society and of life in general.46,47 In this case, a reactive and proportional emotion to an unpleasant life event could be misinterpreted as pathological, while is a temporal, self-limited, legitimate, adaptative and necessary emotion to face the vicissitudes of life.40,48 In fact, several studies have demonstrated the high prevalence of subthreshold depressive symptoms in PC and the prescription of AD in this population despite the lack of evidence on their efficacy,49 especially in comparison to other effective interventions such as psychotherapies.50,51 These circumstances make it more challenging for GPs to reach a definitive diagnosis as there is usually a very thin and grey threshold between psychological distress and an explicit mental health diagnosis, especially when a decision needs to be made in just one short visit.52 For instance, a meta-analysis analyzing data from more than 50,000 cases in PC found that a false-positive diagnosis of depression is 50% more frequent in comparison to cases correctly diagnosed or missed.53 In fact, the three more prevalent diagnoses from our sample included Unspecified Anxiety (F41), Adjustment (F43), and Depressive (F32) disorders. This is in line with the most reported mental health problems in PC, namely anxiety and depression symptoms usually triggered by a life-stressor, which is usually conceptualized as a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. Despite their high prevalence, there has been little research on adjustment disorders, and neither their conceptualization, nor the biological underpinnings of the disorder have been clarified.54 Even the most effective treatments for the disorder, either psychotherapeutic55 or pharmacological56 are yet to be determined. Future research should explore risk and protective factors specific to adjustment disorder, and disorder-specific interventions should be developed and evaluated.54

We have recently seen the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic pushing an already overloaded PC system to its limits with substantial increases in mental health problems and prescription of psychotropic medications worldwide.57,58 It remains unclear the long-term effects of the pandemic and if and how long this increase of mental health problems and prescriptions will remain with some initial reports it is already receding.59 However, the recent pandemic serves yet as another example of the urgent need of a more robust and solid PC system as any adverse societal event directly and indirectly impact populations’ mental health.60

In this line, there are an increasing number of initiatives in PC to optimize the appropriate and rational use of AD in PC despite its incipient results. As an example, a training initiative by the World Health Organization (WHO) for GPs and nurses to integrate mental health care into PC have demonstrated to effectively resolve mild to moderate mental health issues in PC.38 Computerized decisions support tools have shown better outcomes in comparison to routine care in PC61,62 and others promising projects in the same line are currently being tested.63 Moreover, programmes to facilitate access to both conventional and digital (i.e., web, smartphone and chatbot-based) psychological therapies in PC have increase shown positive cost-efficient results.64–69 During the last decade, digital therapies in particular, are opening the door to narrowing and democratizing the gap between the high prevalence of mental health problems in PC and psychological treatments availability.70 In fact, our group is currently working in harnessing the advances in digital treatments and Artificial intelligence (AI) to develop a mental health digital decision-support for GPs in PC to predict severity in mental health and offer personalized psychological, pharmacological treatments and timely specialists’ consultations according to patient's characteristics (www.prestoclinic.cat).25

The new digital tools that have and are being developed should be accessible to everyone. Therefore, research groups and developers need to consider the most vulnerable groups of the population, such as older people, in order to avoid the digital gap. Also, since females seem to be at more risk of receiving an AD, digital tools ought to keep in mind the gender perspective of the interventions offered. Among some, depression and anxiety are more prevalent in women, and symptoms presentation vary widely according to gender (e.g. depressed mood and emotional lability are usually more present in depressed women than men). Furthermore, response to psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression and anxiety vary according to gender (e.g. some AD usually show better results in women than men and vice versa and this may be applied to specific components of psychotherapeutic approaches). Finally, women are bound to different biological and environmental situations than men. For instance, pregnancy, in which depression and anxiety are especially prevalent and urgent to treat, and some pharmacological treatments are contraindicated due to teratogenic risk. Other gender-related differential situations include menopause, in which mental health symptoms are also prevalent and require specific management, and gender-based violence of any kind, which has been related with mental health problems, including acute stress, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide.

LimitationsThere were some inherent limitations of working with big data sets such as working with age groups and truncated dates. However, our analyses were not affected by the latter, as we choose to analyze these data as categorical. Another limitation is the sudden decrease and then rise of AD prescriptions between 2018 and 2019 without obvious reasons beyond a delay on the consolidation of public data from one year to another. Curiously, a recent work by Espín-Martínez et al. analyzed public AD prescription registries in the paediatric population in Spain, and also found a decrease in AD prescription in the year 2018.71

Also, the increasing off-label use of AD for other very frequent conditions in PC such as chronic pain, fibromyalgia, insomnia and migraine which could overestimate the percentages.30,1 Although we could not discard this possibility, especially since amitriptyline was one of the most frequent AD. Amitriptyline at lower doses also has indication for migraine prophylaxis and chronic pain which seems to be the most frequent use in our sample considering the lower average dose of 22mg. However, the total cumulative percentual variation during the study period for amitriptyline was an increase of only 30% making a very small contribution to the overall 404% increase on AD prescriptions we found.

Lastly, another point worth mentioning is the possibility that some individuals of the cohort were under specialized mental health care at the private sector. This a possibility that cannot be determined by the data available at PADRIS-AQuAs registries and it has been estimated that around 20% patients had double (public and private) health coverage in Catalonia.72 Even in those circumstances, the EHR software (ECAP) that is used throughout the Catalan Health System only allows the prescription of medications by GPs that are associated with a clinical diagnosis. This reduced the bias, since many people consulting the private sector also have their prescriptions updated in the public register. Moreover, some patients with mental health problems requiring AD may have been missed since they are unable or unwilling to contact with the health services, due to lack of insight or stigma. This may indicate that the results found in this study may be even more marked. In that sense, a strength of this study is that the cohort excluded all potential individuals requiring specialized mental health care during the 10 years periods. Hence, results reflect as accurate as possible the AD prescription situation in PC independently of severe cases requiring more complex and long-term use of pharmacological treatments.25

This study allows us to take a close look at the precedent decade, not to startle readers, but to provide a critical analysis of the past in order to design strategies for a better future. Future directions hint towards the implementation of digital solutions in concordance with strengthening the mental health (especially psychological) resources in PC and provide personalized treatments. In addition, there is a need to promote the training of GPs on mental health, and endorse the educational policies of the population from an early age to facilitate identification and management of mental health problems and combat stigma to allow timely and appropriate consultations.

ConclusionOur results from a large population-representative cohort of non-psychiatric patients attending PC, confirm a steady increase of AD prescriptions in the Catalan PC system on the decade that preceded the COVID-19 pandemic that is not explained by a parallel increase in mental health diagnoses with an indication for AD. A trend on AD off-label and over prescriptions in the PC system in Catalonia can be inferred from this dissociation. Variables associated with increased risk of being prescribed an AD were female sex, older age, and lower socio-economic status. These results emphasize the need to further promote programmes allowing GPs to optimize their diagnosis, referrals and treatment decisions as well as facilitate access to therapeutic resources such as cost-efficient psychological treatments in PC.

Authors’ contributionsGA, MS, and DH drafted the first version of the manuscript. DH, MC, EV and GA designed the project, studies and drafted the manuscript. DH and GA coordinated the project development with the involved companies. JB advised and coordinated the data analysis with PADRIS-AQuAS. CVB, VAN, and JFMC performed the data extraction and its anonymization from PADRIS-AQuAS. JR, AS, and MF revised and suggested the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed and improved the final version of the manuscript.

Consent for publicationAnonymized data were extracted from electronic health records accessed by the Data Analytics Programme for Health Research and Innovation (PADRIS).

Availability of data and materialsDataset used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and according with the limitations in the agreement between PADRIS-AQuAS and the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona.

FundingThis study has been funded by a Pons Bartran 2020 research grant (project PI046549).

Conflicts of interestDr. Anmella has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck/Otsuka, and Angelini, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Dr. Murru has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Angelini, Idorsia, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Takeda, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Dr. Zahn has collaborations with EMIS PLC, Depsee Ltd, and EMOTRA, received honoraria from Lundbeck and Janssen and is a co-I for a Livanova-funded study, and provides private healthcare. Prof. Young received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards for all major pharmaceutical companies with drugs used in affective and related disorders with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Dra Cavero has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Lundbeck, Esteve, Pfizer, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Prof. Vieta has received research support from or served as consultant, adviser or speaker for AB-Biotics, Abbott, Abbvie, Adamed, Angelini, Biogen, Celon, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo SmithKline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Organon, Otsuka, Rovi, Sage pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, and Viatris, out of the submitted work. Dr. Hidalgo-Mazzei received CME-related honoraria or adviser from Abbott, Angelini, Janssen-Cilag and Ethypharm with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

This study has been carried out using the anonymized data ceded by the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AQuAS), within the framework of the Data Analytics Programme for Health Research and Innovation (PADRIS) (https://aquas.gencat.cat/). The PRESTO project is funded by Fundació Clínic per a la Recerca Biomèdica through the Pons Bartan 2020 grant (PI046549). Dr. Anmella is supported by a Rio Hortega 2021 grant (CM21/00017) from the Spanish Ministry of Health financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-financed by the Fondo Social Europeo Plus (FSE+). Dr. Sanabra's research is supported by a grant from Baszucki Brain Research Fund. Dr. Fico is supported by a fellowship from “La Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) – fellowship code – LCF/BQ/DR21/11880019. Dr. Martinez-Aran thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI18/00789, PI21/00787) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the ISCIII; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365), the CERCA Programme, and the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya for the PERIS grant SLT006/17/00177. Dr. Vieta thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PI15/00283, PI18/00805, PI19/00394, CPII19/00009) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII)-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the ISCIII; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365), and the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. We would like to thank the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya for the PERIS grant SLT006/17/00357. Dr. Murru thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI19/00672) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Dr. Radua is supported by a Miguel Servet Research ContractCPII19/00009 from theInstituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funded by European Union (ERDF/ESF, ‘Investing in your future’). Dr. Hidalgo-Mazzei's research is supported by a Juan Rodés JR18/00021 granted by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII). We would like to thank the PADRIS Programme for their administrative and statistical support as well as the CERCA Programme, and the Generalitat de Catalunya for the institutional support.