Older Adults with Bipolar Disorder (OABD) show cognitive impairments with a negative impact on psychosocial functioning and quality of life. However, to date any intervention for the improvement of functioning has been developed for OABD. The current project aims to demonstrate the efficacy of the Functional Remediation program (FR) specifically adapted to OABD, over 60 years old, for improving functional outcome.

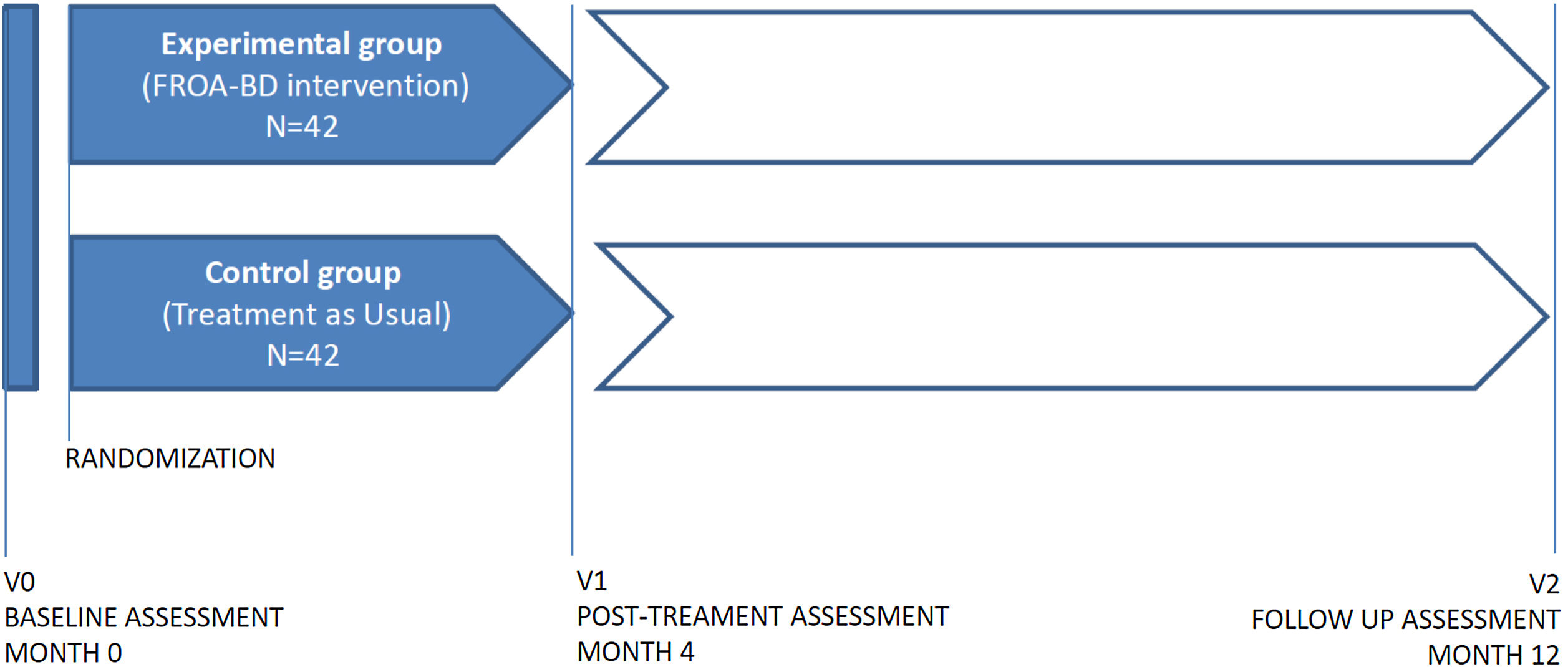

MethodsThis is an experimental, randomized-controlled trial. Two groups will be included: the experimental group (n=42) will receive a 4-month intervention consisting of 32 sessions of treatment and the control group which will receive treatment as usual (TAU) (n=42). The intervention will result from the adaptation of the Functional Remediation program for OABD (FROA-BD), that has already proven its efficacy at improving psychosocial functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Clinical, neuropsychological and functional evaluations will be carried out at baseline, post-intervention and follow-up (one year after baseline evaluation). We hypothesized that patients who have undergone the intervention FROA-BD will improve their psychosocial functioning, cognitive performance, quality of life and well-being. We also hypothesized that all these changes will remain stable after eight month follow-up.

ConclusionsThe results will provide evidence of the efficacy in improving psychosocial functioning, cognitive performance and quality of life applying the FROA-BD. This project consists in the first attempt to adapt the FR program to OABD population who needs specific needs and approaches. The novelty of this contribution represents an advance in the framework of psychological treatment in later-life bipolar disorder.

Los pacientes con trastorno bipolar en edad avanzada (TBEA) muestran alteraciones cognitivas que suponen un impacto negativo en el funcionamiento psicosocial y en la calidad de vida. Sin embargo, hasta la fecha no se ha desarrollado ninguna intervención para la mejora del funcionamiento psicosocial en TBEA. El presente proyecto tiene como objetivo demostrar la eficacia del programa de rehabilitación funcional (RF) adaptado a pacientes con trastorno bipolar (TB) mayores de 60 años en la mejora del funcionamiento psicosocial.

MétodosSe trata de un ensayo clínico experimental, aleatorizado y controlado. Se incluirán dos grupos: el grupo experimental (n = 42) que recibirá una intervención de 4 meses con un total de en 32 sesiones de tratamiento, y el grupo control que recibirá el tratamiento habitual (TAU) (n = 42). La intervención (FROA-BD) será el resultado de la adaptación a TBEA del programa de RF que ya ha demostrado su eficacia para mejorar el funcionamiento psicosocial en pacientes con TB. Se realizarán evaluaciones clínicas, neuropsicológicas y de funcionamiento al inicio de la intervención, después y en el seguimiento (un año después de la evaluación inicial). Nuestra hipótesis es que los pacientes que han recibido la intervención FROA-BD mejorarán en el funcionamiento psicosocial, rendimiento cognitivo, calidad de vida y bienestar. También se hipotetiza que todos estos cambios se mantendrán estables en el periodo de seguimiento (ocho meses tras la intervención).

ConclusionesLos resultados proporcionarán evidencia de la eficacia de FROA-BD en la mejora del funcionamiento psicosocial, en el rendimiento cognitivo y en la calidad de vida de los pacientes con TBEA. Este proyecto supone un primer intento de adaptar el programa de RF a los adultos mayores con TB, población que requiere abordajes y enfoques específicos. La novedad de esta contribución representa un avance en el marco del tratamiento psicológico en el TBEA.