In 2011 there were 94,920 petty offences for lesions, 136,907 crimes against people's life, integrity and liberty,1 11,347 seriously wounded individuals and 104,280 individuals with serious injuries caused by traffic accidents.2 Consequently, 347,454 individuals presented physical and/or mental lesions. Posttraumatic mental disorder (PTMD) is a disorder triggered by an external agent (of physical or mental nature) that can involve legal and economic repercussions. For legal assessment of PTMD, you need to know the type of lesion, its seriousness, the treatments received, its progression, time periods required for recovery and, principally, the individual's functionality once “lesion stability” is achieved; that is, the situation in which there is no possibility of improvement because all the scientifically accepted treatments have been applied. This implies that the both the expert and psychiatric reports have to focus on the diagnosis, on the seriousness and on the repercussion that the disability causes in the individual's life. There are some unique characteristics in PTMD3: (1) it can be produced with or without brain injury; (2) experiencing the trauma can trigger or worsen symptoms, and (3) there can be disproportion among trauma, symptoms and functionality.

To unify the parameters used to assess injuries, the use of required scales has been spreading. Although these scales may be imperfect and incomplete for quantifying personal injuries,4 they have approached functionality, attempting to make a separation from the symptoms.5 Among European Union members, until 1995 only Belgium, Spain, Greece and Portugal applied official scales for classifying or quantifying personal injury from road accidents.6 The other countries have used non-official scales, such as Mélennec's7 French scale, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health8 or the “permanent impairment” guide published by the American Medical Association.9 In Spain, what are called psychiatric syndromes, as well as their scoring, are currently covered by a scale including the stipulations of Law 34/2003 (on modification and adaptation to Community legislation of private insurance companies),10 Community regulations on private insurance legislation, and Legislative Royal Decree 8/2004, of 29 October (approving the restated text of the law on civil responsibility and insurance in motor vehicle circulation.11 There are several difficulties involved in applying this scale. Firstly, the terminology used does not conform to current psychiatric classifications (the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5]12,13). Secondly, the scale omits the specification of the procedure for establishing a score range (except in en el organic personality disorder). Finally, the margins are narrow and the score is limited with respect to mental sequelae14 (except for, once again, organic personality disorder). Given all of the preceding, a single sequela can receive a different score depending on the experience and knowledge of the individual examining the patient.

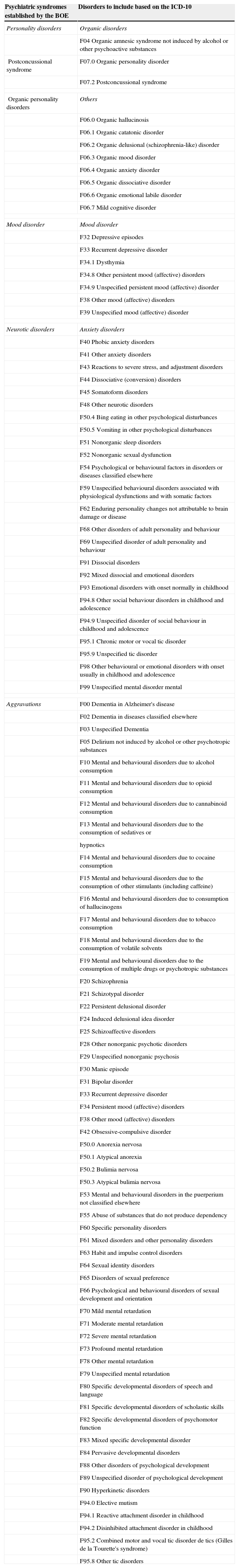

Consequently, we present a PTMD scoring procedure that adapts the current scale to the ICD-10 nosology12 and specifies an assessment method that unifies PTMD scoring. This procedure does not involve a modification of the present scale; it represents a clearer, more unified use of it.

MethodsA work group was established, consisting of a set of experts (2 judges appointed by the General Council of the Judiciary and 4 psychiatrists appointed by the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health, of which 2 were, in addition, medical pathologists). This work group prepared an initial draft procedure, which different professional forums then discussed. An example is Documentos Córdoba 2011, a meeting of law professionals (judges, public prosecutors and lawyers) and psychiatrists, published by the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health.15 There were several presentations about the legal and psychiatric need to unify the traffic scoring scale, discussing the proposal presented by the work group. This proposal was unanimously accepted and then a small legal modification was incorporated. Later, following the same method, it was presented at the 15th National Psychiatry Congress (Oviedo, 2011), at a monographic meeting (Sevilla, 2011), in collaboration with the Centre for Excellence in Forensic Research in Andalucía, about the subject with 25 forensic doctors from different autonomous communities in Spain, at which the authors (judges, psychiatrists and psychiatrists-forensic doctors) presented the reasons for the procedure; and, finally, at the 16th National Psychiatry Congress (Bilbao, 2012).

ProcedureEvaluation prior to scoringExpert evaluation should be based on “lesion stability”, the time when the lesion or mental disorder does not progress positively in spite of the treatment prescribed. Childhood psychiatric signs and symptoms need to be framed, for their evaluation, in the overall attitude of the parents in the face of the causal traumatic facts.

Diagnoses: concordance with the current scaleAs indicated previously, the ICD-10 diagnoses12 referring to mental diseases are linked to the psychiatric syndromes included in the official scale. To do so, the scale subsections would be changed to the current diagnoses (Table 1). To make application possible, the diagnosis has to fulfil the same criteria as those gathered in the ICD-10.12

Proposal for the ICD-10 disorder classification based on the organisation of psychiatric syndromes established by the Spanish Official Gazette (BOE).

| Psychiatric syndromes established by the BOE | Disorders to include based on the ICD-10 |

|---|---|

| Personality disorders | Organic disorders |

| F04 Organic amnesic syndrome not induced by alcohol or other psychoactive substances | |

| Postconcussional syndrome | F07.0 Organic personality disorder |

| F07.2 Postconcussional syndrome | |

| Organic personality disorders | Others |

| F06.0 Organic hallucinosis | |

| F06.1 Organic catatonic disorder | |

| F06.2 Organic delusional (schizophrenia-like) disorder | |

| F06.3 Organic mood disorder | |

| F06.4 Organic anxiety disorder | |

| F06.5 Organic dissociative disorder | |

| F06.6 Organic emotional labile disorder | |

| F06.7 Mild cognitive disorder | |

| Mood disorder | Mood disorder |

| F32 Depressive episodes | |

| F33 Recurrent depressive disorder | |

| F34.1 Dysthymia | |

| F34.8 Other persistent mood (affective) disorders | |

| F34.9 Unspecified persistent mood (affective) disorder | |

| F38 Other mood (affective) disorders | |

| F39 Unspecified mood (affective) disorder | |

| Neurotic disorders | Anxiety disorders |

| F40 Phobic anxiety disorders | |

| F41 Other anxiety disorders | |

| F43 Reactions to severe stress, and adjustment disorders | |

| F44 Dissociative (conversion) disorders | |

| F45 Somatoform disorders | |

| F48 Other neurotic disorders | |

| F50.4 Bing eating in other psychological disturbances | |

| F50.5 Vomiting in other psychological disturbances | |

| F51 Nonorganic sleep disorders | |

| F52 Nonorganic sexual dysfunction | |

| F54 Psychological or behavioural factors in disorders or diseases classified elsewhere | |

| F59 Unspecified behavioural disorders associated with physiological dysfunctions and with somatic factors | |

| F62 Enduring personality changes not attributable to brain damage or disease | |

| F68 Other disorders of adult personality and behaviour | |

| F69 Unspecified disorder of adult personality and behaviour | |

| F91 Dissocial disorders | |

| F92 Mixed dissocial and emotional disorders | |

| F93 Emotional disorders with onset normally in childhood | |

| F94.8 Other social behaviour disorders in childhood and adolescence | |

| F94.9 Unspecified disorder of social behaviour in childhood and adolescence | |

| F95.1 Chronic motor or vocal tic disorder | |

| F95.9 Unspecified tic disorder | |

| F98 Other behavioural or emotional disorders with onset usually in childhood and adolescence | |

| F99 Unspecified mental disorder mental | |

| Aggravations | F00 Dementia in Alzheimer's disease |

| F02 Dementia in diseases classified elsewhere | |

| F03 Unspecified Dementia | |

| F05 Delirium not induced by alcohol or other psychotropic substances | |

| F10 Mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol consumption | |

| F11 Mental and behavioural disorders due to opioid consumption | |

| F12 Mental and behavioural disorders due to cannabinoid consumption | |

| F13 Mental and behavioural disorders due to the consumption of sedatives or | |

| hypnotics | |

| F14 Mental and behavioural disorders due to cocaine consumption | |

| F15 Mental and behavioural disorders due to the consumption of other stimulants (including caffeine) | |

| F16 Mental and behavioural disorders due to consumption of hallucinogens | |

| F17 Mental and behavioural disorders due to tobacco consumption | |

| F18 Mental and behavioural disorders due to the consumption of volatile solvents | |

| F19 Mental and behavioural disorders due to the consumption of multiple drugs or psychotropic substances | |

| F20 Schizophrenia | |

| F21 Schizotypal disorder | |

| F22 Persistent delusional disorder | |

| F24 Induced delusional idea disorder | |

| F25 Schizoaffective disorders | |

| F28 Other nonorganic psychotic disorders | |

| F29 Unspecified nonorganic psychosis | |

| F30 Manic episode | |

| F31 Bipolar disorder | |

| F33 Recurrent depressive disorder | |

| F34 Persistent mood (affective) disorders | |

| F38 Other mood (affective) disorders | |

| F42 Obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| F50.0 Anorexia nervosa | |

| F50.1 Atypical anorexia | |

| F50.2 Bulimia nervosa | |

| F50.3 Atypical bulimia nervosa | |

| F53 Mental and behavioural disorders in the puerperium not classified elsewhere | |

| F55 Abuse of substances that do not produce dependency | |

| F60 Specific personality disorders | |

| F61 Mixed disorders and other personality disorders | |

| F63 Habit and impulse control disorders | |

| F64 Sexual identity disorders | |

| F65 Disorders of sexual preference | |

| F66 Psychological and behavioural disorders of sexual development and orientation | |

| F70 Mild mental retardation | |

| F71 Moderate mental retardation | |

| F72 Severe mental retardation | |

| F73 Profound mental retardation | |

| F78 Other mental retardation | |

| F79 Unspecified mental retardation | |

| F80 Specific developmental disorders of speech and language | |

| F81 Specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills | |

| F82 Specific developmental disorders of psychomotor function | |

| F83 Mixed specific developmental disorder | |

| F84 Pervasive developmental disorders | |

| F88 Other disorders of psychological development | |

| F89 Unspecified disorder of psychological development | |

| F90 Hyperkinetic disorders | |

| F94.0 Elective mutism | |

| F94.1 Reactive attachment disorder in childhood | |

| F94.2 Disinhibited attachment disorder in childhood | |

| F95.2 Combined motor and vocal tic disorder de tics (Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome) | |

| F95.8 Other tic disorders | |

When a diagnosis of mental sequela had occurred previously, it will be recorded as aggravation, and symptom intensity and degree of disability will be calculated as the difference resulting from the mental sequelae before and after the event.

Indication of the severity of the symptomsThe severity of the posttraumatic suffering will be evaluated according to the number and intensity (temporal frequency) of the symptoms present reported in the clinical history and examination, always based on the nosographic criterion description established for each entity in the ICD-10 international classification.12 To diagnose with this classification, the subject evaluated has to fulfil the minimum criteria specified for each entity. Starting from these minimums, the type of severity will be indicated in the following gradients:

- -

Moderate: up to 40 points. Subject fulfils the minimum number of required criteria established in the ICD-10 for diagnosis.

- -

Intense: up to 60 points. Exceeds the symptoms by 20% over the minimums required for this diagnosis.

- -

Very intense: up to 80 points. Exceeds the symptoms by 40% over the minimums required for this diagnosis and/or 1 of them is extremely severe.

- -

Extreme: 100 points. Has the maximum number of symptoms described for this diagnosis and/or several of them are extremely severe.

The category “Mild” would be eliminated, given that it supposes the existence of isolated psychopathological symptoms and/or indeterminate and diffuse mental distress that do not cause a decrease in the subject's functional capacities, with normal activities being maintained.

Degree of disability produced by the symptoms presentDisability means the difficulties for a subject's autonomous life and/or the negative repercussions on their working life.16 In this section we assume the specifications of Royal Decree 1971/1999, of 23 December, on the procedure for recognising, declaring and rating the degree of disability,17 and its posterior correction.18

Psychiatric sufferingThe concept of psychiatric suffering is incorporated into the scale. As indicated by the consensus group, such suffering should consider not only the severity of the sequelae but also the degree of disability that the illness produced or aggravated means for that subject. Consequently, psychiatric suffering would be the result of adding the scores for symptom intensity and disability and dividing both [the sum] by 2 (PS=[pS+pD]/2, where PS is the psychiatric suffering; pS, the points for severity of the disorder; and pD, the points for disability). In posttraumatic aggravation of pre-existing mental illness, it is necessary to obtain the difference of both scores, from the period before to that after the traumatism.

The maximum score for psychiatric suffering is 100. Consequently, we have to adapt this to the intervals that the current scale indicates for each of the syndromes referenced, taking the minimum and maximum scores into consideration. Thus, pSc=pmSc+(PS [pMSc−pmSc]/100), where pSc are the points of the scale; PS, the psychiatric suffering, pMSc, the maximum point score that is applied to the disorder; and pmSc, the minimum point score in the scale applied to the disorder.

LimitationsThis proposal has been established by means of a series of experts that have agreed on the procedures with other professionals. This method implicitly involves the subjectivity of those involves in its preparation. Further studies are required in which the validity of the procedure proposed is assessed, along with the difference that might exist between it and the current form of assessing mental harm.

FundingThe study presented was funded by the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health and by the Consortium for Excellence in Forensic Research in Andalucía.

In addition to the agencies that funded this study (mentioned in the previous section), we wish to thank the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health and the General Council of the Judiciary for their scientific support and facilitation. Likewise, we thank Antonia Rodríguez and Samuel Aidan Kelly for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Guija JA, Medina A, Giner L, Lledó C, Marín A, Arechederra JJ, et al. Un nuevo método de valoración de la enfermedad psiquiátrica postraumática. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:245–250.