Looked-after children are among the most vulnerable groups in our society, who suffer from a greater likelihood of poor educational, social and mental health outcomes. The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action released a technical note1 aimed at supporting child care practitioners and government officials in their response to the child protection concerns faced by children during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, especially those at risk of separation or in alternative care. As child and adolescent psychiatrists, we must continue to work with other medical and civil organizations in an advocacy effort to address the needs of this vulnerable group of young people.

In this Special article, we review previous social and economic disruptions and their impact on children and their families, and then discuss vulnerabilities caused by the COVID-19 crisis. Finally, we provide some ideas on how pediatric and adolescent practitioners can help socially disadvantaged children.

Lessons learned from previous economic and health crisesThe socioeconomic disruption caused by the Great Recession of 2008 was associated with adverse child mental health and well-being outcomes in subsequent years. The poorest and most vulnerable children suffered the greatest impact of the economic decline and possibly for the longest time.2 It has been demonstrated that parents’ psychological distress resulting from financial loss reduces their parenting skills and leads to impaired parent–child interactions, which are associated with a greater likelihood of contact with child protection services.3

Lockdown can be particularly challenging for children and adolescents, especially for those with neuropsychiatric conditions or disabilities, and for those in vulnerable social circumstances (for instance, refugee or migrant children, children living in alternative care or overcrowded settings, and those who have recently left alternative care).4,5

Evidence from previous health emergencies indicates that existing child protection risks are exacerbated, and new ones emerge, as a result not only of the epidemic, but also of the socioeconomic impact of the associated prevention and infection control measures.1 Children are at heightened risk when schools are closed, social services are interrupted, and movement is restricted.6 For instance, the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa resulted in spikes in child labor, neglect, sexual abuse, and teenage pregnancies, with specific gender-based violence focused against girls and young women.6 Moreover, adolescents could be more vulnerable to the consequences of physical distancing measures, as this coincides with a sensitive period for the onset of mental health problems, and peer interactions are important for healthy brain and social development.7

Impact of COVID-19 and related control measures on children and adolescentsWhile pandemic-related measures adopted to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19 are necessary to reduce the disease burden,1 public health authorities need to be aware of the potential negative consequences, deepening children's social, educational, and health inequalities.

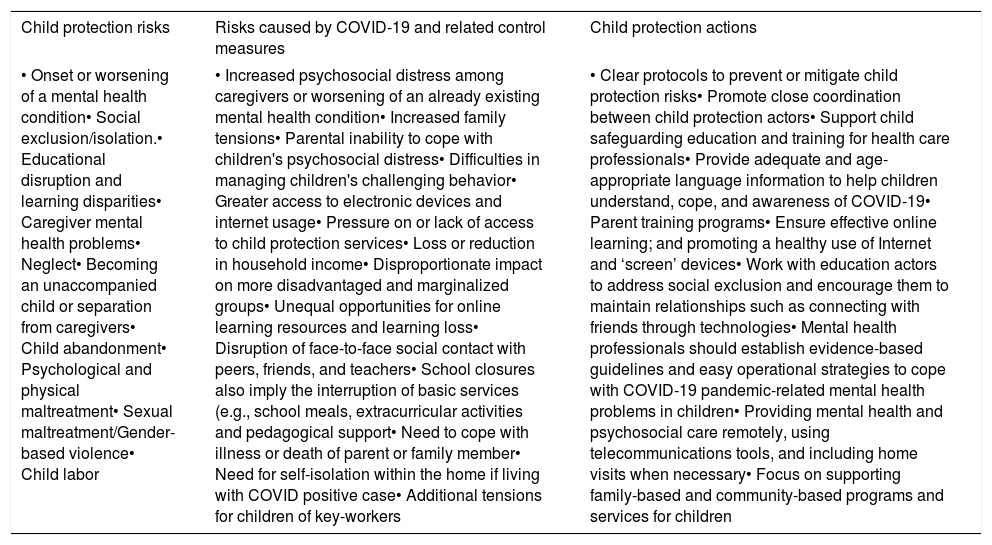

Stressors such as family and friendship disruptions, frustration, lack of personal space, reduced psychosocial support, inadequate information, and family financial loss may have detrimental and enduring effects on the development and wellbeing of children and adolescents. Table 1 captures the specific psychosocial and mental health problems that may arise during the current crisis, and the potential ways they can lead to harmful consequences.

A summary of the protection risks for children that can arise from COVID-19 outbreak, and actions that are required to prevent and respond to different child protection needs.

| Child protection risks | Risks caused by COVID-19 and related control measures | Child protection actions |

|---|---|---|

| • Onset or worsening of a mental health condition• Social exclusion/isolation.• Educational disruption and learning disparities• Caregiver mental health problems• Neglect• Becoming an unaccompanied child or separation from caregivers• Child abandonment• Psychological and physical maltreatment• Sexual maltreatment/Gender-based violence• Child labor | • Increased psychosocial distress among caregivers or worsening of an already existing mental health condition• Increased family tensions• Parental inability to cope with children's psychosocial distress• Difficulties in managing children's challenging behavior• Greater access to electronic devices and internet usage• Pressure on or lack of access to child protection services• Loss or reduction in household income• Disproportionate impact on more disadvantaged and marginalized groups• Unequal opportunities for online learning resources and learning loss• Disruption of face-to-face social contact with peers, friends, and teachers• School closures also imply the interruption of basic services (e.g., school meals, extracurricular activities and pedagogical support• Need to cope with illness or death of parent or family member• Need for self-isolation within the home if living with COVID positive case• Additional tensions for children of key-workers | • Clear protocols to prevent or mitigate child protection risks• Promote close coordination between child protection actors• Support child safeguarding education and training for health care professionals• Provide adequate and age-appropriate language information to help children understand, cope, and awareness of COVID-19• Parent training programs• Ensure effective online learning; and promoting a healthy use of Internet and ‘screen’ devices• Work with education actors to address social exclusion and encourage them to maintain relationships such as connecting with friends through technologies• Mental health professionals should establish evidence-based guidelines and easy operational strategies to cope with COVID-19 pandemic-related mental health problems in children• Providing mental health and psychosocial care remotely, using telecommunications tools, and including home visits when necessary• Focus on supporting family-based and community-based programs and services for children |

There is accumulating evidence on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic-related issues on children's mental health and well-being. Data from the first wave of COVID-19 in European countries showed that parents perceived a significant increase in their children's emotional, behavioral, and restless/attentional difficulties.8,9 Mental health problems appear to have decreased after the lockdown eased and through schools opened in September. However, when new restrictions were introduced, parental distress increased, with higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety, particularly among low-income families and parents of children with special educational needs.8

Family environments marked by poverty or limited resources will bear the full brunt of COVID-19 and associated containment measures. High-stress home environments increase the likelihood of family conflicts, as well as emotional and behavioral problems, domestic abuse and violence.2 The negative impact of loneliness and social isolation disproportionately affects children from disadvantaged backgrounds, thereby contributing to growing concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate existing health and social inequalities.4

Addressing mental health and psychosocial aspects of the COVID-19 outbreakIdeally, the integration of mental health concerns into COVID-19 care should be addressed through collaborative networks between child protection actors, pediatricians and mental health professionals, who should all be aware of mechanisms for preventing, identifying, and delivering psychosocial support to children and adolescents and their caregivers.4Table 1 lists the key strategies for providing psychosocial support to children that should be incorporated as part of the response to COVID-19.

A number of economic institutions worldwide have stated that the COVID-19 pandemic will increase poverty and global inequalities.4 It is expected that the number of children at risk of family separation and in need of alternative care will increase – both during the peak of the crisis and as a result of its long-term socio-economic impact on families’ capacity to care. Positive parenting skills become even more important when children are confined at home. Furthermore, access to extended family, who before the pandemic often provided critical support to primary caregivers in the care of children, is likely to be limited during home-based quarantines due to restrictive confinement measures in elders and general limitations of movement. This change poses an addition challenge which may contribute to an increasing need for residential care settings in vulnerable children.10

Coordinated child protection effortsIn light of the growing economic crisis and the extensive psychological distress surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, child psychosocial needs are increasing and require an immediate response from child protection and mental health services. The strategy must be inclusive of key risk groups such as children with disabilities.

Governments and local authorities should offer continuing support to families and communities to prioritize keeping children safe in family environments. Enabling families to cope with this situation will require reducing stressors such as food and economic instability and increasing parenting capabilities, along with mental health support.10 Such support can enhance family resilience and help minimize the need for residential care.

We suggest that an inter-agency collaboration between child protection, education, and mental health services should be adopted in the design and development of programs targeting the specific challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, we call on governments, health institutions, and non-governmental organizations to include and prioritize the needs of children and young people in any discussion or implementation of COVID-19 responses. If children's needs are not appropriately addressed, the mental health consequences for a generation of children could far exceed the immediate health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving long-term social and economic consequences.

FundingThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this work.

DisclosuresDr Solerdelcoll receives grant support from the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. Dr Arango has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Instituto de Salud Carlos III (SAM16PE07CP1, PI16/02012, PI19/024), co-financed by ERDF Funds from the European Commission, “A way of making Europe”, CIBERSAM. Madrid Regional Government (B2017/BMD-3740 AGES-CM-2), European Union Structural Funds. European Union Seventh Framework Program under grant agreements FP7-4-HEALTH-2009-2.2.1-2-241909 (Project EU-GEI), FP7-HEALTH-2013-2.2.1-2-603196 (Project PSYSCAN) and FP7-HEALTH-2013-2.2.1-2-602478 (Project METSY); and European Union H2020 Program under the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (grant agreement no. 115916, Project PRISM, and grant agreement no. 777394, Project AIMS-2-TRIALS), Fundación Familia Alonso and Fundación Alicia Koplowitz. Dr Sugranyes has received research support from the Spanish Ministry of Science (PI18/00696) integrated in the National Plan of I+D+I and co-financed by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Fundació Clínic Recerca Biomèdica (Ajut a la Recerca Pons Bartran, FCRB_PB1_2018).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Inmaculada Baeza, MD, PhD, and Luisa Lazaro, MD, PhD, of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, for their guidance and comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.