Intensive treatment in acute day-care psychiatric units may represent an efficient alternative to inpatient care. However, there is evidence suggesting that this clinical resource may not be equally effective for every psychiatric disorder.

The primary aim of this study was to explore differences between main psychiatric diagnostic groups, in the effectiveness of an acute partial hospitalization program. And, to identify predictors of treatment response.

Material and methodsThe study was conducted at an acute psychiatric day hospital. Clinical severity was assessed using BPRS, CGI, and the HoNOS scales. Main socio-demographic variables were also recorded. Patients were clustered into 4wide diagnostic groups (i.e.: non-affective psychosis; bipolar; depressive; and personality disorders) to facilitate statistical analyses.

ResultsA total of 331 participants were recruited, 115 of whom (34.7%) were diagnosed with non-affective psychosis, 97 (28.3%) with bipolar disorder, 92 (27.8%) with affective disorder, and 27 (8.2%) with personality disorder. Patients with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder showed greater improvement in BPRS (F=5.30; P=0.001) and CGI (F=8.78; P<0.001) than those suffering from psychosis or depressive disorder. Longer length of stay in the day-hospital, and greater baseline BPRS severity, were identified as predictors of good clinical response. Thirty-day readmission rate was 3%; at long-term (6 months after discharge) only 11.8% (N=39) of patients were re-admitted to a psychiatric hospitalization unit, and no differences were observed between diagnostic groups.

ConclusionsIntensive care in an acute psychiatric day hospital is feasible and effective for patients suffering from an acute mental disorder. However, this effectiveness differs between diagnostic groups.

El tratamiento intensivo y agudo en unidades psiquiátricas de ingreso a tiempo parcial puede representar una alternativa eficaz a los ingresos hospitalarios a tiempo completo. Sin embargo, existe evidencia que indica que estos dispositivos podrían no ser igualmente eficaces para todos los trastornos psiquiátricos.

El objetivo primario del estudio fue explorar las diferencias entre los principales grupos de diagnóstico psiquiátrico en la efectividad de un programa de hospitalización parcial aguda, así como identificar predictores de respuesta al tratamiento.

Material y métodosEl estudio se realizó en un hospital psiquiátrico de día. La gravedad clínica se evaluó mediante las escalas BPRS, CGI y HoNOS. También se recogieron variables sociodemográficas. Los pacientes se agruparon en 4grupos diagnósticos amplios (psicosis no afectiva, bipolar, depresión, trastornos de la personalidad).

ResultadosSe seleccionó a 331 participantes, 115 de los cuales (34,7%) fueron diagnosticados de psicosis no afectiva, 97 (28,3%) de trastorno bipolar, 92 (27,8%) de trastorno afectivo y 27 (8,2%) de trastorno de personalidad. Los pacientes con trastorno bipolar mostraron una mayor mejoría BPRS (F=5,30; p=0,001) y CGI (F=8,78; p<0,001) que aquellos que presentaban psicosis o trastorno depresivo. Estancias más prolongadas en el hospital de día y una mayor gravedad inicial (BPRS) fueron factores predictores de buena respuesta. La tasa de reingreso en unidad psiquiátrica a los 30 días del alta fue del 3% y del 11,8% en los siguientes 6 meses.

ConclusionesEl cuidado intensivo en una unidad psiquiátrica de día es factible y eficaz para los pacientes con un trastorno mental agudo. Sin embargo, esta eficacia difiere entre los grupos de diagnóstico.

Intensive care of acute psychiatric patients, using partial hospitalization in an acute psychiatric day hospital, is becoming a relevant component of community care. It delivers personalized and intensive mental health care in a service that combines the close supervision of a standard acute psychiatric inpatient unit with the maintenance of patients in the community, using a less restrictive and stigmatizing clinical environment.1,2 For this, a structured treatment milieu, combining somatic-biological and psychotherapeutic methods, is generally used. From a clinical management perspective, the objectives of these units in the care of patients with acute and severe mental illness should be to prevent their admission into an acute psychiatric inpatient unit and/or to shorten their stay period in an acute inpatient unit.1 To facilitate the achievement of these objectives, these units should be closely associated with other psychiatric facilities, and ideally located in a general hospital.

There has been a series of studies comparing the efficacy of these units against the treatment provided in acute psychiatric inpatient units. The results tend to demonstrate that they could be regarded as a viable and cost-effective treatment alternative.2–6 However, it has not been addressed whether these alternative services are equally effective for the different psychiatric disorders. In fact, the meta-analysis by Horvitz-Lennon and colleagues,7 in accordance with other studies,3,8–10 reported no clear answer about which psychiatric pathology would benefit most from acute partial hospitalization in an acute psychiatric day hospital.

An additional key issue is the identification of predictors of treatment response for this modality of treatment. Previous research identified certain clinical factors, such as symptoms’ severity prior to admission that could be used as predictors for treatment response in these clinical programs.11 Similarly, some patients’ socio-demographic characteristics also appear to play a significant role in the patient's clinical response.6,10,12,13 However, studies on this area are scarce, limited to partial aspects, and often conducted on a reduced number of psychiatric cases. Thus, further research is needed to identify valid predictors of outcome for the treatment of acute and severe psychiatric patients in an acute psychiatric day hospital.

The aim of this study is to analyze the clinical outcome of a series of acute psychiatric patients treated in an acute psychiatric day hospital of a general hospital; secondly, to identify possible differences in the effectiveness of this modality of treatment in different mayor psychiatric disorders; and thirdly, to identify valid predictors of treatment response for those patients.

Material and methodsStudy design and settingThe study was conducted at an acute psychiatric day hospital. The catchment area of the unit covers the Autonomous Community of Cantabria, in Northern Spain.14 All patients, aged 18 years and older, and admitted to the unit between January 2015 and January 2017, were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) to have a main DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis of: non-affective psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, mood and anxiety disorders, personality disorder; (2) to present acute symptomatology for which the patient needed acute intensive treatment; and (3) to be voluntarily admitted to the acute psychiatric day hospital. Patients were excluded if they presented an organic brain syndrome, disruptive or aggressive behavior, active suicidality, severe substance abuse or an insufficient social support to be treated through partial hospitalization in the acute psychiatric day hospital.

The acute psychiatric day hospital team is formed by a psychiatrist, a psychologist, 4 mental-health specialized nurses, a social worker and an occupational therapist. The treatment provided is multi-component, following a bio-psycho-social approach, including psycho-pharmacological strategies and manual and evidence-based psychotherapy interventions (cognitive-behavioral therapy), both in individual and group settings.

All patients signed an informed consent to treatment and to the collection of information for evaluation and research purposes.

Clinical assessmentPatient's clinical status and severity were assessed at admission and prior to discharge from the unit, by the same experienced psychiatrist (JVB), using the assessment instruments established in the acute psychiatric day hospital's functional plan.15 Clinical severity was evaluated using the 24-items version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-E)16 and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI).17 The level of Social adjustment was evaluated using the HoNOS questionnaire,18 in particular with its social sub-scale (items 9–12). Socio-demographic characteristics were recorded at admission through a specifically design questionnaire. Primary diagnoses were established by means of DSM-IV criteria.

Outcome measuresOutcome was evaluated using the following criteria: (1) level of psychopathological and social improvement as measured by the different assessment instruments; (2) mean duration of treatment needed to achieve sufficient clinical improvement for being discharged; and (3) 30-day and 180-day readmission rates to an acute psychiatric hospitalization unit (either the acute psychiatric inpatient unit or the acute psychiatric day hospital) after discharge from the acute psychiatric day hospital.

Predictor measuresWe explored if baseline characteristics predicted outcome after treatment. Predictor variables included age, gender, marital status, employment status, living arrangements and social support. Baseline measures of clinical severity were also included as predictors.

Data analysesFor statistical analysis, patients were grouped according to four wide diagnostic categories (i.e.: non-affective psychosis; bipolar disorder; depressive disorder; personality disorder). Descriptive statistics were applied to generate a sample profile based on demographic and clinical data. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables were used for comparisons between groups.

To compare clinical improvement between diagnoses subgroups, univariate ANCOVA tests were applied, where mean differences (baseline minus discharge scores) in symptoms’ severity were defined as dependent variables and diagnostics groups as the independent variable. Relevant clinical and socio-demographic variables, including those significantly associated with diagnostic categories in earlier analyses (i.e.: baseline severity, gender, age, social support and civil status) were entered as co-variables.

Finally, to identify predictors of “better response”, chi-square and ANOVA tests were applied. “Better response” was defined using a nonspecific and broader BPRS criterion due to the heterogeneity of the sample, and according to previous research19; a reduction of 30% or more in the BPRS total score at discharge. Subsequently, those variables significantly associated to “better response”, and other relevant variables derived from previous research, were entered into a binary logistic regression model, where “better response” was the dependent variable. Secondary analyses with binary logistic regression models for each diagnostic group were carried out. The performance of the models was examined via Nagelkerke's R2, a measure of the proportion of explained variation in the logistic regression models. In addition, logistic regression yields odds ratios (ORs), which provide an additional measure of the strength of association. The percentage of patients correctly classified by the model and the proportion of variance explained, including the individual contribution of each variable to the model (OR), were investigated.

All the secondary analyses were two-tailed. The Statistical Package for Social Science, version 19.0 (SPSS Inc.,Chicago, IL, USA), was used. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

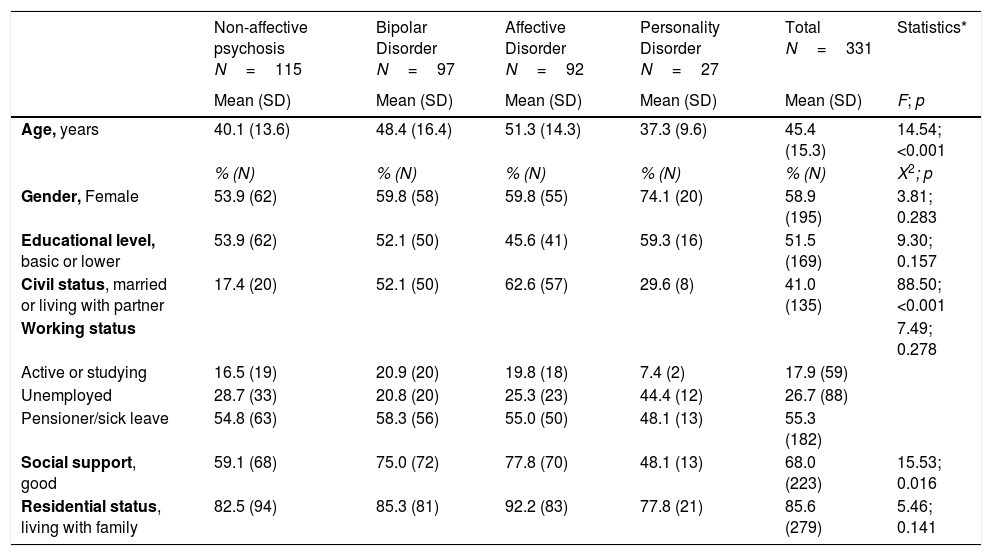

ResultsBaseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristicsA total of 331 subjects were included in the study. Among them, 115 (34.7%) had a diagnosis of non-affective psychosis, 97 (28.3%) of bipolar illness, 92 (27.8%) of affective disorder and 27 (8.2%) of personality disorder. The mean age of the total population was 45.4 years (SD=15.3). The diagnostic groups were similar regarding the socio-demographic characteristics (Table 1) except for civil status and social support. Patients with a diagnosis of non-affective psychosis were less frequently married (X2=88.50; p<0.001) and presented a lower social support (X2=15.53; p<0.016).

Socio-demographic characteristics.

| Non-affective psychosis N=115 | Bipolar Disorder N=97 | Affective Disorder N=92 | Personality Disorder N=27 | Total N=331 | Statistics* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F; p | |

| Age, years | 40.1 (13.6) | 48.4 (16.4) | 51.3 (14.3) | 37.3 (9.6) | 45.4 (15.3) | 14.54; <0.001 |

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | X2; p | |

| Gender, Female | 53.9 (62) | 59.8 (58) | 59.8 (55) | 74.1 (20) | 58.9 (195) | 3.81; 0.283 |

| Educational level, basic or lower | 53.9 (62) | 52.1 (50) | 45.6 (41) | 59.3 (16) | 51.5 (169) | 9.30; 0.157 |

| Civil status, married or living with partner | 17.4 (20) | 52.1 (50) | 62.6 (57) | 29.6 (8) | 41.0 (135) | 88.50; <0.001 |

| Working status | 7.49; 0.278 | |||||

| Active or studying | 16.5 (19) | 20.9 (20) | 19.8 (18) | 7.4 (2) | 17.9 (59) | |

| Unemployed | 28.7 (33) | 20.8 (20) | 25.3 (23) | 44.4 (12) | 26.7 (88) | |

| Pensioner/sick leave | 54.8 (63) | 58.3 (56) | 55.0 (50) | 48.1 (13) | 55.3 (182) | |

| Social support, good | 59.1 (68) | 75.0 (72) | 77.8 (70) | 48.1 (13) | 68.0 (223) | 15.53; 0.016 |

| Residential status, living with family | 82.5 (94) | 85.3 (81) | 92.2 (83) | 77.8 (21) | 85.6 (279) | 5.46; 0.141 |

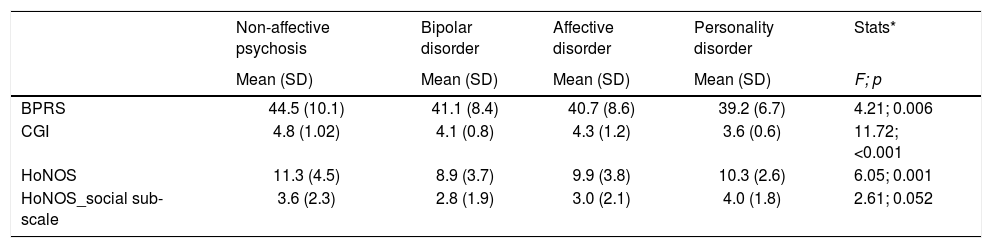

A significant association between diagnostic groups and baseline level of clinical severity was detected (Table 2). Post hoc analyses revealed that those patients with a diagnosis of non-affective psychosis were admitted to the acute psychiatric day hospital with significantly higher scores in the BPRS scale than those with bipolar or affective disorder (p=0.052 and p=0.019, respectively). Similarly, these patients presented higher scores in the CGI scale than those with bipolar, affective and personality disorders (p<0.001, p=0.002, and p<0.001, respectively). Finally, non-affective psychosis patients showed at baseline higher scores in the HoNOS scale than those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (p<0.001).

Baseline severity.

| Non-affective psychosis | Bipolar disorder | Affective disorder | Personality disorder | Stats* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F; p | |

| BPRS | 44.5 (10.1) | 41.1 (8.4) | 40.7 (8.6) | 39.2 (6.7) | 4.21; 0.006 |

| CGI | 4.8 (1.02) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.3 (1.2) | 3.6 (0.6) | 11.72; <0.001 |

| HoNOS | 11.3 (4.5) | 8.9 (3.7) | 9.9 (3.8) | 10.3 (2.6) | 6.05; 0.001 |

| HoNOS_social sub-scale | 3.6 (2.3) | 2.8 (1.9) | 3.0 (2.1) | 4.0 (1.8) | 2.61; 0.052 |

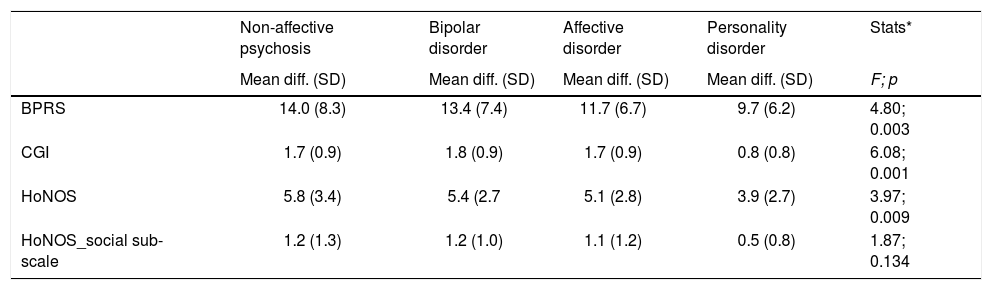

A significant association between diagnostic groups and improvement in clinical severity and social adjustment was found (Table 3). The post hoc-analyses (Bonferroni correction) showed that those patients with bipolar disorder presented greater improvements in BPRS than those with unipolar affective disorder (p=0.002). And greater improvements in CGI than those patients with non-affective psychosis, bipolar disorder and personality disorder (p=0.002, p=0.060, and p=0.025, respectively).

Clinical and social improvement after treatment in Acute Day Hospital.

| Non-affective psychosis | Bipolar disorder | Affective disorder | Personality disorder | Stats* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diff. (SD) | Mean diff. (SD) | Mean diff. (SD) | Mean diff. (SD) | F; p | |

| BPRS | 14.0 (8.3) | 13.4 (7.4) | 11.7 (6.7) | 9.7 (6.2) | 4.80; 0.003 |

| CGI | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.8) | 6.08; 0.001 |

| HoNOS | 5.8 (3.4) | 5.4 (2.7 | 5.1 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.7) | 3.97; 0.009 |

| HoNOS_social sub-scale | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.5 (0.8) | 1.87; 0.134 |

Regarding the HoNOS social sub-scale, we found an association between social improvement and diagnoses. Post hoc analyses showed that those patients with a personality disorder presented a significant smaller improvement than those with a bipolar disorder (p=0.042).

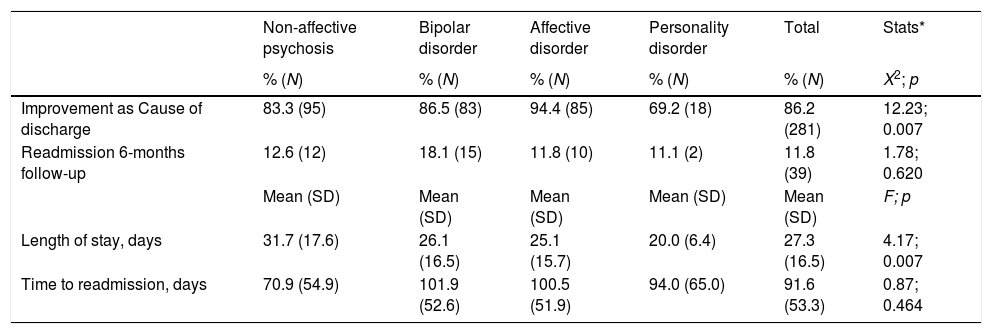

Secondary clinical outcomes: discharge characteristics and readmissionThe analyses of secondary outcomes (Table 4) showed that 86.2% of patients was discharged from the acute psychiatric day hospital after achieving clinical improvement. On the other hand, 8.5% of patients (N=28) had to be transferred from the acute psychiatric day-hospital to a full-time psychiatric hospitalization unit (either the acute psychiatric inpatient unit or the subacute inpatient unit) due to not achieving clinical improvement, or even experiencing a clinical deterioration during their treatment at the acute psychiatric day hospital; those diagnosed with affective disorder were the less transferred to a full-time psychiatric hospitalization unit (3.3% vs. 12.3% of those with non-affective psychosis, 9.3% of bipolar disorders, and 7.4% of personality disorder). Besides, 5.2% (N=17) of patients stopped attending the acute psychiatric day hospital (abandon treatment); those patients with a diagnosis of Personality disorder tended to abandon the treatment against the clinical advice more frequently than other patients (23.1% vs. 4.4% of non-affective psychosis, 4.2% of bipolar disorders, and 2.2% of affective disorder).

Secondary outcomes.

| Non-affective psychosis | Bipolar disorder | Affective disorder | Personality disorder | Total | Stats* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | X2; p | |

| Improvement as Cause of discharge | 83.3 (95) | 86.5 (83) | 94.4 (85) | 69.2 (18) | 86.2 (281) | 12.23; 0.007 |

| Readmission 6-months follow-up | 12.6 (12) | 18.1 (15) | 11.8 (10) | 11.1 (2) | 11.8 (39) | 1.78; 0.620 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F; p | |

| Length of stay, days | 31.7 (17.6) | 26.1 (16.5) | 25.1 (15.7) | 20.0 (6.4) | 27.3 (16.5) | 4.17; 0.007 |

| Time to readmission, days | 70.9 (54.9) | 101.9 (52.6) | 100.5 (51.9) | 94.0 (65.0) | 91.6 (53.3) | 0.87; 0.464 |

The global mean length of stay in the acute psychiatric day hospital was 27.3 days (SD=16.5), being significantly different in the various diagnostic groups (F=4.17, p=0.007). Post hoc analyses (Bonferroni) showed that those patients with a non-affective psychosis presented longer stays in the unit than those with affective or personality disorders (p=0.044 and p=0.033, respectively).

Only 3% of patients (N=10) had to be readmitted to an acute psychiatric hospitalization unit (either the acute psychiatric day hospital or the acute psychiatric inpatient unit) within the first 30 days after being discharged from the acute psychiatric day hospital. The mean time to re-admission was 16.9 days after day-hospital discharge. Readmission to an acute psychiatric hospitalization unit during the 6 months following discharge from the acute psychiatric day hospital was also analyzed as an indicator of long-term outcome (Table 4). We found that only 11.8% of patients (N=39) needed to be re-admitted in the following 6 months after being discharged. We did not found, however, any significant differences between diagnostic groups in the readmission rates. The mean length of time to re-admission was 91.6 days (SD=53.3). The mean number of days to readmission was smaller in non-affective psychosis, the difference not reaching statistical significance.

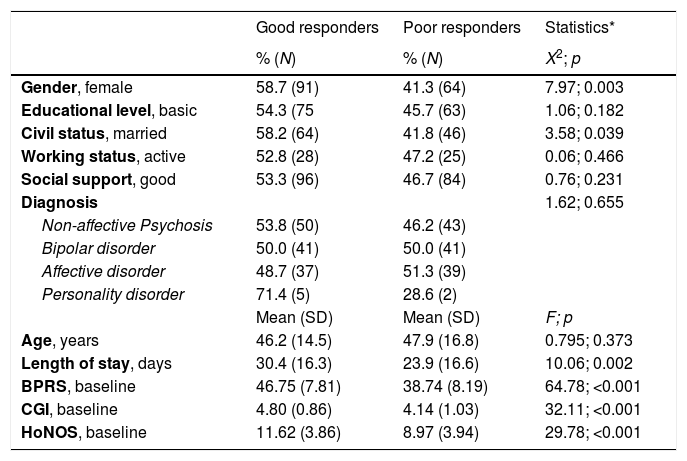

Prediction of clinical responseAt discharge, 133 patients (51.6%) were classified as having had a “better response”, which was significantly associated with gender (female), (X2=7.968, p=0.003), civil status (married) (X2=3.581, p=0.039), longer length of stay (F=10.056, p=0.002), and greater baseline clinical severity (BPRS: F=64.78, p<0.001; CGI: F=32.11, p<0.001; and HoNOS: F=29.78, p<0.001) (Table 5). In the subsequent predictor model (binary logistic regression) only length of stay in the acute psychiatric day hospital (OR=0.963; 95% CI=0.929–0.998; p=0.038) and baseline BPRS (OR=1.155; 95% CI=1.074–1.243; p<0.001) emerged as significant predictors. This model (X2(12)=63.82, p<0.001) predicted “response” with 76.5% accuracy and correctly classified 75.2% of ‘better responder’ patients and 77.8% of those with ‘poor response’.

Predictors of better clinical response.

| Good responders | Poor responders | Statistics* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | X2; p | |

| Gender, female | 58.7 (91) | 41.3 (64) | 7.97; 0.003 |

| Educational level, basic | 54.3 (75 | 45.7 (63) | 1.06; 0.182 |

| Civil status, married | 58.2 (64) | 41.8 (46) | 3.58; 0.039 |

| Working status, active | 52.8 (28) | 47.2 (25) | 0.06; 0.466 |

| Social support, good | 53.3 (96) | 46.7 (84) | 0.76; 0.231 |

| Diagnosis | 1.62; 0.655 | ||

| Non-affective Psychosis | 53.8 (50) | 46.2 (43) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 50.0 (41) | 50.0 (41) | |

| Affective disorder | 48.7 (37) | 51.3 (39) | |

| Personality disorder | 71.4 (5) | 28.6 (2) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F; p | |

| Age, years | 46.2 (14.5) | 47.9 (16.8) | 0.795; 0.373 |

| Length of stay, days | 30.4 (16.3) | 23.9 (16.6) | 10.06; 0.002 |

| BPRS, baseline | 46.75 (7.81) | 38.74 (8.19) | 64.78; <0.001 |

| CGI, baseline | 4.80 (0.86) | 4.14 (1.03) | 32.11; <0.001 |

| HoNOS, baseline | 11.62 (3.86) | 8.97 (3.94) | 29.78; <0.001 |

The prediction model was, however, significantly improved when applied to each of the diagnostic groups separately (for complete results see Supplementary material), predicting “better response” with higher accuracy.

DiscussionWe examined the main characteristics of the psychiatric patients admitted to an acute psychiatric day hospital based in a general hospital, as well as the clinical and social outcomes of treatment, and their prediction. The study demonstrates that globally the care provided in this unit is capable of producing a significant level of clinical improvement in a wide range of patients affected by acute psychiatric illness belonging to major diagnostic groups. This is very much in accordance with previous studies that have demonstrated that intensive treatment in an acute psychiatric day hospital is, at least, equally cost-effective than the one delivered on acute psychiatric inpatient units, for a considerable proportion of patients suffering from an acute and severe psychiatric illness.3–5,7 Moreover, due to its characteristics as more “community-oriented”, this setting provides clear advantages for patients, regarding stigma, maintaining social networks, and promoting autonomy, which may be reflected in social improvement, as shown by our results. However, we should emphasize that, as The European Day Hospital Study –EDEN- has demonstrated, day hospitals across countries have not consistent profiles of structural and procedural features, thus making comparisons with other studies to some point questionable.20 In this sense our acute psychiatric day hospital has been classified with the D1 code, according to the ESMS/DESDE methodology.15,21

The above described evidence on effectiveness justified for example, that treatment in an acute psychiatric day hospital was included in the recommendations made by the National Institute of Health Care Excellence (NICE) for the management and prevention of serious mental illness such as psychosis and schizophrenia.22 However, there is evidence suggesting that this sort of clinical service may not be equally effective for every psychiatric disorder. Horvitz-Lennon and colleagues7 conducted a meta-analysis of studies published from 1957 to 1997, and found a non-clear answer to this question, a conclusion which is in accordance with other studies.3,5,8,9,23 Contrary to this, our study found that, compared to other major diagnostic groups, patients with bipolar disorders presented higher level of clinical and social improvement. It is noteworthy that, in our study, the reported differences are especially marked in the comparison with the personality disorder group, which showed the lowest level of improvement, thus confirming previous studies.23 However, other studies have reported the effectiveness of specialized psycho-social interventions in psychiatric day hospitals for patients with severe personality disorders.24,25 These specific interventions are described as highly-structured, specialized and with a long-term duration (18 months).24 In this sense, not having provided an specialized psychosocial interventions to those patients with personality disorder, may be one of the underlying causes of their lesser clinical improvement achieved in our acute psychiatric day hospital. Another possible factor contributing to this difference could be the fact that these patients abandon more frequently the treatment against medical advice. This result goes in line with the findings described by previous authors, and may be due to their difficulty in engaging in treatment and to their postulated ambivalence to mental and behavioral change.26,27

Despite its relevance, research examining predictor variables for the efficacy of acute psychiatric day hospitals is rare, often conducted on a reduced number of psychiatric “cases” and limited to partial aspects.6,10,11,28 Our study identified gender, civil status, length of stay, and baseline clinical severity as predictors of “better clinical response”. However, the prediction model calculated from these and other variables of interest derived of previous studies13 showed that only length of stay and baseline BPRS acted as significant predictors of better clinical response. The model failed to reach robust results, with a 76.5% accuracy in the prediction of response. However, when diagnostic category was separately considered, the prediction models reached accuracies over 80%. We were not able to replicate in our study the relevance of certain key clinical and socio-demographic factors, such as the presence of previous psychiatric hospitalization, co-morbidity, level of motivation, chronicity, social support, and patient's “Subjective Initial Response”, described in previous studies.6,10,12,29–31

It is also important to highlight that readmission to a psychiatric unit is common among individuals with severe mental illness. It has been recently considered as a relevant quality indicator of in-patient psychiatric care, especially during the first 30 days after discharge.32,33 Our study found a 30-day readmission rate limited to 3% of patients, and 11.8% in the following 6 months after discharge from the acute psychiatric day hospital. This figure is placed on the range of international recommended goals of good care,34–36 and it is much lower than the rates reported in other studies, ranging between 40% and 54%.37,38

At the same time, we found no significant differences on the rate and time to re-hospitalization between diagnostic groups, which is in line with a previous study.37 Thus, our finding supports the idea that re-hospitalization is not so much dependent on the diagnostic categories but rather on other relevant clinical, and service-related factors.33,37 In this respect, as the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality emphasizes, further research should also include determining key components that are most effective in keeping those at high risk of re-hospitalization functioning in the community.33 Unfortunately, the small numbers of readmissions in our study limited the possibility of analysing risk factors associated to re-hospitalization, thus not allowing to establish comparisons with other studies.37–43

Limitations and strengthsOur study had some strengths and limitations. The strengths include the prospective methodology, containing a long-term outcome measure (i.e.: readmission in the following 6 months after discharge). Additionally, the naturalistic and observational characteristic of the study, which comprised all patients admitted to the unit from an extensive and well-defined socio-demographic and administrative area (the Autonomous Community of Cantabria), guarantees the analysis of a large and heterogeneous sample of acute psychiatric patients affected by major psychiatric disorders. This facilitates the generalization of the results to other acute psychiatric day hospitals.

However, the study counts with several relevant limitations. First, although our patient population was diverse in diagnostic categories, clinical manifestations and socio-demographic variables, it lacked representativeness in other important aspects. For example, we were unable to include patients who were discarded for admission such as those who did not provide consent for admission, presented severe substance abuse, lacked sufficient family support, or presented a high suicidal risk, thus not allowing generalization of the findings to these clinical groups. Secondly, and in order to facilitate the analysis, we have used rather broad diagnostic categories derived from clinical diagnosis and not from research diagnosis based on standardized instruments. In third place, we clustered the patients regarding their primary psychiatric diagnosis, without taking into consideration possible co-morbidities and personality traits that may had influenced outcome measures. Forth, we have to stress that although a naturalistic study design improves the generalization of findings, it is limited by a lack of control for the effects of important factors influencing the effectiveness of pharmacological and psychological treatment. Finally, the design of this study did not permit to make comparisons with other modalities of intensive in-patient care, thus not allowing making conclusions on the relative advantages and cost-effectiveness of this modality of care.

ConclusionsThe results of this study support the idea that intensive care in an acute psychiatric day hospital is feasible, effective, and capable of achieving significant clinical and social improvements in patients suffering from a wide variety of severe and acute mental illnesses. Its effectiveness is especially marked in bipolar disorder as compared with non-affective psychosis and depressive disorders. Moreover, those patients with personality disorders benefited the less, mainly due to their tendency to abandon the treatment. In the analysis of clinical response, duration of stay in the acute psychiatric day hospital and clinical severity at intake emerged as relevant predictors of better response explaining above 80% of better response in all the clinical groups. In addition, the study of secondary outcome indicators revealed low 30-day and 180-day readmission rates (3% and 11.8%, respectively).. The study, therefore, provides useful data for mental health managers, clinicians and researchers.

Further work should carefully specify the type of service being assessed in terms of structural and procedural features. They should also focus on delineating a better characterization of the predictors of better treatment response and on refining the criteria for admissions to these units. An additional objective should be to compare the clinical, social impact and cost-effectiveness of this model of care for severe psychiatric pathology, with the one provided in other intensive and time limited inpatient mental health services.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing the present study.

This study was carried out at the Acute Day Psychiatric Hospital of the University Hospital Marques de Valdecilla (Santander, Spain), and with the inestimable help from its nursing staff and social worker. Thus, we wish to thank Begoña Agüeros Pérez, Elena Cortázar López, Julia Cuétara Caso, and Concepción Villacorta Alonso.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Bourgon J, Gómez Ruiz E, Hoyuela Zatón F, Salvador Carulla L, Ayesa Arriola R, Tordesillas Gutiérrez D, et al. Diferencias en la efectividad clínica y funcional, entre trastornos psiquiátricos, de un hospital de día psiquiátrico de agudos para pacientes con enfermedad mental aguda. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2021;14:40–49.