To examine the significant differences in smoking, drug and alcohol use between adolescent boys and girls, and to raise the possible need to design and implement prevention programmes from a gender perspective.

MethodA qualitative study using eight discussion groups of adolescents aged 14–18 years (n=56) and 6 semi-structured interviews with experts and professionals in drug prevention in the Community of Madrid. Categorical interpretive analysis was performed.

ResultsThe adolescents and prevention professional indicated differences between boys and girls in drug and alcohol use. The significances, reasons associated with the consumption and the patterns of consumption were perceived differently by each sex. To lose weight, calm down or an image of rebelliousness was related to girls who smoked, while boys smoked less because they participated in more sports. The perception of certain precocity of drug consumption was associated with the step from school to Higher Education Institutions. They found smoking associated with a good social image among their groups. Adolescents showed the ineffectiveness of the campaigns and prevention messages they received, incoherence of adults between messages and actions, and the attraction of all behaviours that are banned. Professionals observed the need to include a gender perspective in prevention programmes, but did not know how to achieve it, mainly because it has been translated into different activities for each sex until now.

ConclusionsThe significant differences associated with smoking, drug and alcohol use observed in the adolescents should lead us to design and implement prevention programmes that incorporate a gender perspective. It is perhaps from this strategy where drug and alcohol use among girls can be reduced.

Explorar los significados diferenciales en el consumo de drogas, tabaco y alcohol entre chicos y chicas, y plantear la posible necesidad de diseñar e implementar los programas de prevención desde una perspectiva de género.

MétodosEstudio cualitativo mediante 8 grupos de discusión con adolescentes de 14–18 años (n=56) y 6 entrevistas semiestructuradas a expertos y profesionales de prevención de drogas en la Comunidad de Madrid. Análisis interpretativo categórico.

ResultadosLos adolescentes y profesionales de prevención señalaban diferencias entre chicos y chicas en los consumos de tabaco y alcohol. Los significados, motivos asociados al consumo y las pautas de consumo eran percibidos de forma diferente en cada sexo. Adelgazar, calmar los nervios o una imagen de rebeldía era relacionada al fumar de las chicas mientras que el menor consumo de tabaco en los chicos se asociaba con su participación en el deporte. La percepción de cierta precocidad en los consumos de drogas se asociaba al paso del colegio al instituto. Constataban la buena imagen social asociada a fumar entre sus grupos. Los adolescentes manifestaron la ineficacia de las campañas y mensajes de prevención que recibían, la incoherencia de los adultos entres sus mensajes y acciones, y la atracción de todas las conductas que les eran prohibidas. Los profesionales observaban la necesidad de incluir la perspectiva de género en los programas de prevención, pero desconocían cómo concretarlo, ya que principalmente lo traducían en actividades diferentes para cada sexo.

ConclusionesLos diferentes significados asociados al consumo que otorgan chicos y chicas nos llevan a diseñar y realizar programas preventivos que incorporen la perspectiva de género, pues es quizá desde esta estrategia desde donde se pueda reducir el consumo de tabaco y alcohol entre las chicas.

Over the last years the surveys designed by the Government Office for the Spanish National Drug Strategy given to secondary school students, as well as other studies,1–3 have been indicating important differences between boys and girls in the consumption of psychoactive substances. The feminine predominance in the consumption of legal substances (tobacco, alcohol and psychiatric drugs) is especially notable. The last Spanish National Survey on Drug Use by Secondary School Students4 shows that there are clear gender differences in the consumption of substances in these ages; boys consume all the illegal drugs in greater proportion than girls, while tobacco and tranquillisers or hypnotics are more consumed by female students. Likewise, the last student survey carried out in Madrid in 20085 indicated that in the last year 35% of the boys and 41.1% of the girls had smoked; 66.9% of boys and 70.5% of girls had consumed alcohol; and 5% of boys and 7.1% of girls had consumed tranquillisers without a prescription. This ratio was also found in the last month's consumption and in the life prevalence. However, these percentages switch when we talk about illegal drugs (hash, cocaine, ecstasy, etc.); the greatest consumptions appear in boys, which once again shows the different patterns of consumption by gender than have been mentioned several times.6,7

Tobacco and alcohol consumption generate in Spain the biggest drug-related problems, in terms of both accident rates and mortality.8 The incorporation of young females in these consumptions will in time lead to an increase in health problems that were of minority interest for them before. What is happening to adolescent girls to make them smoke and drink more than there masculine counterparts? What social representation and meaning do these substances have for these girls? Is it possible for us to think that the preventative strategies based on universal and selective prevention are less effective for girls?

These questions have motivated this research, considering that gender analysis helps to answer them. While in Spain the gender studies on the use and abuse of drugs are few or in the minority, that is not the case in the international context. Since the 1980s gender has been considered an important matter in the treatment of drug abuse9 and, to a lesser extent, in prevention programmes.10,11

The objective of this study was to explore and describe the differential perceptions and meanings in drug consumption (specifically of tobacco and alcohol) between boys and girls, and to pose the possible need to design and implement prevention programmes from a gender perspective.

MethodThe methodological focus used in this study was qualitative, utilising semi-structured interviews and discussion groups. Depending on the data collection technique used, the study subjects were different. Six interviews were given, recorded in audio and transcribed literally; the subjects were professionals at different entities that participated actively in the design or development of programmes of prevention of drug consumption in Madrid (Fundación of Ayuda contra la Drogadicción/Foundation for Help against Drug Addiction, Proyecto Hombre Madrid/Madrid Project Humanity, Madrid City Council, Madrid Red Cross and ATICA Health Services).

There were also 8 discussion groups including young people that were selected based on criteria of homogeneity (sex, type of education centre, area) and heterogeneity (sex, age, school year, consumption and non-consumption, type of consumption) in the Autonomous Community of Madrid (Table 1). The distribution was as follows: 2 mixed-sex groups, 1 group of only boys and 5 groups of only girls. In all there were 56 adolescent participants, from 14 to 18 years old; 26.8% males and 73.2% females. This majority of girls was intentional, to capture better the thoughts of girls. The mean age was 16 years (standard deviation=0.959); the students mainly attended the 4th and 5th years of Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE) (80.3%).

Data summary of the discussion groups with adolescents.

| Discussion groups | Profiles of the participants |

| GD1 | 9 girls (girls) |

| 14–18 years old | |

| 3rd year CSE to upper 6th Form (there are girls in the 4 courses) | |

| Subsidised school | |

| Western area of the Community of Madrid | |

| Upper middle class | |

| Consumption of alcohol, tobacco and psychoactive drugs. Two non-consuming girls | |

| GD2 | 4 girls and 5 boys (mixed) |

| 16–18 years old | |

| 4th year CSE to lower 6th Form | |

| State school | |

| Northern area | |

| Middle class | |

| Consumption of alcohol, tobacco and hash | |

| GD3 | 3 boys and 2 girls (mixed) |

| 16 years old | |

| Lower 6th Form (the students from CSE failed to come) | |

| State school | |

| Northern area | |

| Lower middle class | |

| 2 non-consumers, the rest consumers of tobacco, alcohol and hash | |

| GD4 | 5 girls (girls) |

| 16–17 years old | |

| 4th year CSE | |

| Private school | |

| Northern area | |

| High class | |

| 2 non-consumers and 3 consumers of alcohol, tobacco and hash | |

| GD5 | 4 girls (girls) |

| 16–17 years old | |

| 4th year CSE | |

| Private school | |

| Northern area | |

| High class | |

| 2 non-consumers and 2 consumers of alcohol, tobacco and hash | |

| GD6 | 8 girls (girls) |

| 4th year CSE | |

| Northern area | |

| Middle class | |

| State school | |

| All consumers of alcohol and tobacco, except for a Muslim girl that smoked hash | |

| GD7 | 8 girls (girls) |

| 3rd and 4th year CSE | |

| Eastern area | |

| Low class (blue-collar workers) | |

| State school | |

| 3 non-consumers, 5 consumers of alcohol, tobacco (1 of tranquillisers) | |

| GD8 | 7 boys (boys) |

| 4th year CSE and lower 6th Form | |

| Eastern area | |

| Low class (blue-collar workers) | |

| State school | |

| 2 non-consumers, 5 consumers of alcohol and tobacco (1 of hash) |

The discussion groups took place in the educational centres that had previously agreed to collaborate. All the young people participating had their parents’ written consent or authorisation, after receiving information about the purpose of the research. After the discussion groups finished, the young people were asked to fill in a very short questionnaire that would make it possible for us to collect their consumption profiles later. The groups were recorded in audio, and afterwards the students received a written confidentiality commitment and a gift for participating. The groups and interviews were carried out during the 2009–2010 school year.

Once the interviews and group discussions had been transcribed word-for-word, we performed a categorical interpretive analysis with the computer support of the programme Atlas ti v.6®. The concepts and categories obtained from a detailed reading of the data served as an initial stage for reduction and abstraction, which made a posterior coding of all the groups and interviews possible. Establishing the connections between categories and concepts was the next stage, which permitted the interpretation, guided at all times by the study objectives, research questions and the references consulted. The results are presented in Table 2 (Verbatim comments of the adolescents [VA]) and Table 3 (Verbatim comments of the professionals [VP]). We achieved saturation of content in the groups, mainly in the girls’ comments. This saturation is explained by 2 factors: on the one hand, there are more groups of girls than of boys and, on the other, because the main motives and circumstances associated with tobacco and alcohol consumption that the girls indicated were repeatedly expressed in the various discussion groups.

Verbatim comments of the adolescents in the discussion groups.

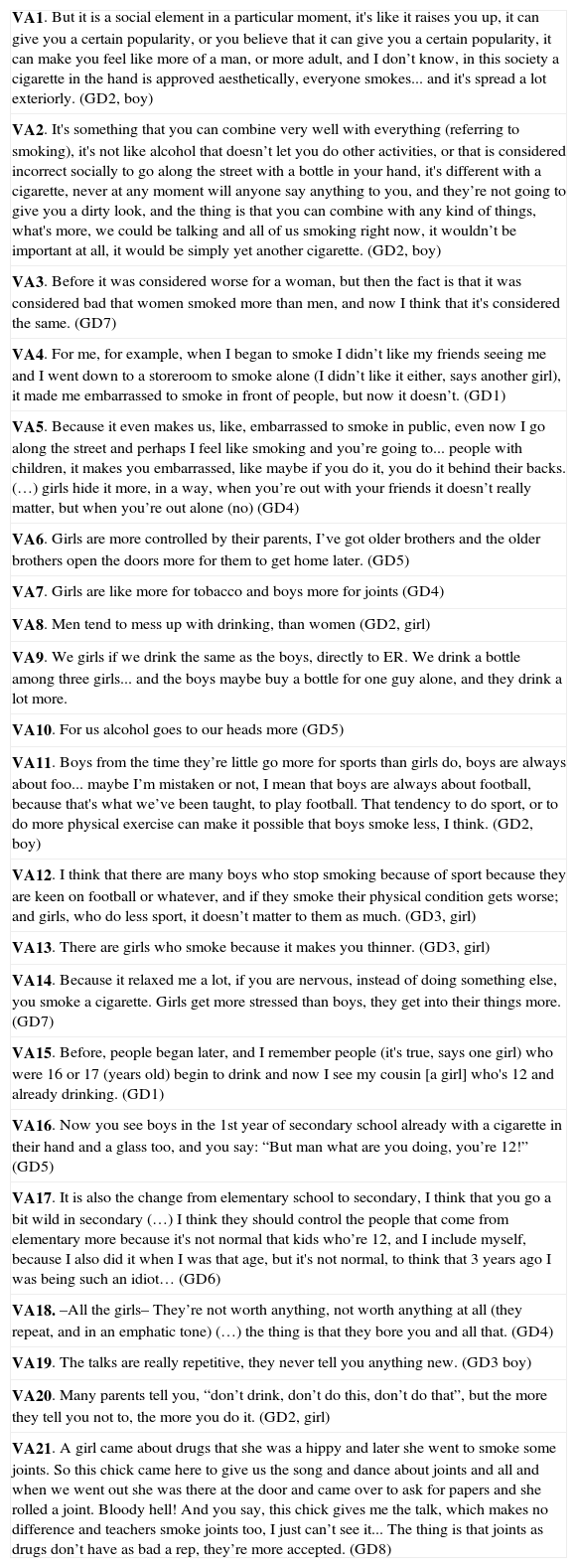

| VA1. But it is a social element in a particular moment, it's like it raises you up, it can give you a certain popularity, or you believe that it can give you a certain popularity, it can make you feel like more of a man, or more adult, and I don’t know, in this society a cigarette in the hand is approved aesthetically, everyone smokes... and it's spread a lot exteriorly. (GD2, boy) |

| VA2. It's something that you can combine very well with everything (referring to smoking), it's not like alcohol that doesn’t let you do other activities, or that is considered incorrect socially to go along the street with a bottle in your hand, it's different with a cigarette, never at any moment will anyone say anything to you, and they’re not going to give you a dirty look, and the thing is that you can combine with any kind of things, what's more, we could be talking and all of us smoking right now, it wouldn’t be important at all, it would be simply yet another cigarette. (GD2, boy) |

| VA3. Before it was considered worse for a woman, but then the fact is that it was considered bad that women smoked more than men, and now I think that it's considered the same. (GD7) |

| VA4. For me, for example, when I began to smoke I didn’t like my friends seeing me and I went down to a storeroom to smoke alone (I didn’t like it either, says another girl), it made me embarrassed to smoke in front of people, but now it doesn’t. (GD1) |

| VA5. Because it even makes us, like, embarrassed to smoke in public, even now I go along the street and perhaps I feel like smoking and you’re going to... people with children, it makes you embarrassed, like maybe if you do it, you do it behind their backs. (…) girls hide it more, in a way, when you’re out with your friends it doesn’t really matter, but when you’re out alone (no) (GD4) |

| VA6. Girls are more controlled by their parents, I’ve got older brothers and the older brothers open the doors more for them to get home later. (GD5) |

| VA7. Girls are like more for tobacco and boys more for joints (GD4) |

| VA8. Men tend to mess up with drinking, than women (GD2, girl) |

| VA9. We girls if we drink the same as the boys, directly to ER. We drink a bottle among three girls... and the boys maybe buy a bottle for one guy alone, and they drink a lot more. |

| VA10. For us alcohol goes to our heads more (GD5) |

| VA11. Boys from the time they’re little go more for sports than girls do, boys are always about foo... maybe I’m mistaken or not, I mean that boys are always about football, because that's what we’ve been taught, to play football. That tendency to do sport, or to do more physical exercise can make it possible that boys smoke less, I think. (GD2, boy) |

| VA12. I think that there are many boys who stop smoking because of sport because they are keen on football or whatever, and if they smoke their physical condition gets worse; and girls, who do less sport, it doesn’t matter to them as much. (GD3, girl) |

| VA13. There are girls who smoke because it makes you thinner. (GD3, girl) |

| VA14. Because it relaxed me a lot, if you are nervous, instead of doing something else, you smoke a cigarette. Girls get more stressed than boys, they get into their things more. (GD7) |

| VA15. Before, people began later, and I remember people (it's true, says one girl) who were 16 or 17 (years old) begin to drink and now I see my cousin [a girl] who's 12 and already drinking. (GD1) |

| VA16. Now you see boys in the 1st year of secondary school already with a cigarette in their hand and a glass too, and you say: “But man what are you doing, you’re 12!” (GD5) |

| VA17. It is also the change from elementary school to secondary, I think that you go a bit wild in secondary (…) I think they should control the people that come from elementary more because it's not normal that kids who’re 12, and I include myself, because I also did it when I was that age, but it's not normal, to think that 3 years ago I was being such an idiot… (GD6) |

| VA18. –All the girls– They’re not worth anything, not worth anything at all (they repeat, and in an emphatic tone) (…) the thing is that they bore you and all that. (GD4) |

| VA19. The talks are really repetitive, they never tell you anything new. (GD3 boy) |

| VA20. Many parents tell you, “don’t drink, don’t do this, don’t do that”, but the more they tell you not to, the more you do it. (GD2, girl) |

| VA21. A girl came about drugs that she was a hippy and later she went to smoke some joints. So this chick came here to give us the song and dance about joints and all and when we went out she was there at the door and came over to ask for papers and she rolled a joint. Bloody hell! And you say, this chick gives me the talk, which makes no difference and teachers smoke joints too, I just can’t see it... The thing is that joints as drugs don’t have as bad a rep, they’re more accepted. (GD8) |

Verbatim comments of the professionals interviewed.

| VP1. “… well in a purely descriptive phenomenon plane, when we analyse frequency of risk behaviour, ride drunk in cars, get into fights, provoke fights, have sexual relations without condoms, in absolute terms, boys do it more than girls, but the girls are divided into 2 groups, some that don’t do risk behaviours at all and others who do it much more, much more than the boys and you say, well... it is happening there... well, so, the truth is that we do not know how to do it.” (Interview 02) |

| VP2.“What I notice is the difference in the development of girls’ consumption in these last few years, that they consume more, more alcohol and with a more cocky approach, of why not, why can’t I consume, they exhibit it more, before girls hid more, now they don’t and tobacco yes, they smoke more, it's incredible.” (Interview 05) |

| VP3. “Yes, as I said, the equality of women is all very well but at the end we find ourselves with a class of 30 sheep, what has it served for the girls to abandon this stereotype of femininity, of we aren’t going to spit in someone's face, or I have found lots of kids at the door of the secondary school spitting and instead of being the boys the ones that get cosy with the most stereotypical behaviours of the girls it has been the complete opposite, the girls, but because socially, and they say it in the workshops, the thing is that the masculine attitude is still valued more than the feminine.” (Interview 06) |

| VP4. “… you hear it more and more, differential consumption between men and women, it's beginning to be differentiated, which is something very positive that hasn’t been happening until now and of course it is necessary, both in adult programmes and those for youngsters, it is also something that is beginning to be thought about, something has to be done, they are not the same consumptions, they are not the same set of problems and they also may need differentiated spaces where each of the circumstances can be handled. And the truth is that in prevention, when you called me I said, ah, well it's true, why not in prevention…” (Interview 03) |

| VP5. “We sincerely believe in personalised intervention programmes and that is for boys, girls, dogs… (Laughter). What I want to tell you is that we adapt to whether it is a young chap in a situation of social exclusion, an unaccompanied minor, or that is, the greatest difficulty, we work in personalised attention with people who are different because of gender, or that is, because of their personal circumstances, starting points in education, language, in the entire setting that surrounds the person there needs to be different adaptations and the referral or connection with different resources and that is our objective.” (Interview 01) |

| VP6. The thing is that perhaps they are the things that would have caught our attention and that we would have questioned but at the moment because the request was not given to us it wasn’t clear either, that is why I tell you that what we lacked was a mirror that made us see all those innate data and that made us see the need. (Interview 02) |

| VP7. “… and if you want to do something that represents a differential study I think it wouldn’t work because a group of girls wouldn’t accept working in a differentiated way separated from the boys”. (Interview 02) |

| VP8. “… it is important, it would be a good idea to consider it, we all reach the same point but nobody gives more specific guidelines and how it is done, how is that really translated into specific actions that should be included in a programme, this type of things perhaps it isn’t necessary, I don’t know, because the subject is there, or how it is managed if it is that way, really this controversy that is happening is real because in practice it is hard to decide what is to be done, the boys are mixed or not, how it is done.” (Interview 04) |

| VP9. “… in Spain we insist on denying the impact that gender involves, in saying, that all of us are equal so if you make a differential manoeuvre they even get angry, we don’t know how to do it, (…) because starting from the supposition that in Spain there has been a sexual and egalitarian revolution that has the effect that we are all equal and that's in everyone's head, when you dig a bit there are just as many differences as in the 1960s, it's tragic, you can’t get your head around it (…) the problem is that from the beginning there is a manoeuvre of negation, they tell you, no, we are all equal it is … then, how do I do it? if I am equal to and I want them to treat me equally, what strategies do I use. In America we are clear about working with boys, with girls and together, here we don’t know how, it is much clearer there and the entire world knows it. No only is it not accepted here but rather that it is not even seen, it is that we are all the young people that now feel the same, but I don’t see it, I don’t know how to do it, but, and this comes from way back, I think the 1st research I did on drugs in 1982.” (Interview 04) |

From the different subjects dealt with in the groups of adolescents, we can focus on 2: the perceived differences between what boys and girls about drug consumption, and the image they had of the preventative anti-consumption interventions they had received. We will now give further details on these 2 matters.

Adolescent perceptions of gender differences in consumptionAdolescents generally perceived differences in consumption of each sex. The main differences mentioned were as follows:

- -

First of all, and despite the perception that smoking was not frowned upon socially (VA1), that is, that neither of the 2 genders had any negative connotations (VA3), some girls indicated that they did not like to smoke in public and that they generally preferred to smoke in private (VA4-VA5). This was the opposite of what various boys said, which emphasises the visibility of smoking against how drinking is hidden; they felt that you could not drink in public but you could smoke tobacco publicly (VA2). The girls’ privacy could be related to parental control over them, given that they commented that they felt that their parents treated them with discrimination with respect to how parents treated boys (VA6); the girls felt that boys were indulged or got permission to do more than them within the family context. Other studies7 have revealed that women tend to consume psychoactive substances more privately than men do. In this sense, the consumption of tobacco or alcohol would not be equally permitted for boys and girls.

- -

Secondly, the substances consumed were perceived to be different depending on gender, mainly speaking about smoking. Boys smoked less tobacco and more hash, while the opposite was true for girls (VA7). In the case of alcohol, there did not seem to be any differences in the type of alcohol consumed, or at least the adolescents did not mention this in their comments. However, the girls did notice a greater intensity of consumption by boys over girls (VA8). Boys had greater resistance to alcohol consumption, drinking a greater amount, while the girls perceived that if they smoked or drank more it affected them physically to a greater extent than it did boys (VA9-VA10), and they showed more moderate behaviours.

- -

In third place, it was posed that boys smoked less than girls and that this was related to boys’ involvement in sport and physical activities, with this involvement being greater in boys than in girls (VA11-VA12). Participating in sport was seen as incompatible with smoking.

- -

In fourth place, we found similarities and differences among the motivations for consumption. Curiosity, influence and integration in the group were factors shared by both sexes. However, losing weight, showing an image of rebelliousness and calming feelings of stress or nervousness were found among the reasons that the girls gave for smoking, but were not mentioned by the boys (VA13-VA14).

The adolescents also indicated differences in perception with respect to consumption by age, not only by gender. It was mentioned that many younger boys and girls began to smoke very early and this was frowned upon, especially when the students smoking were in the 1st course of the CSE (VA15-VA16). Smoking was perceived to be associated with an activity for adults or for older boys and girls. This image acted as the main attraction for initiation in the younger children. Sex and age interacted jointly, producing intersectionality,12 in such a way that smoking was more attractive and had more positive meanings for the youngest girls than for the boys of the same age. Girls usually develop before boys and generally go out with older boys; the meaning of using tobacco and alcohol may be associated with these circumstances. The decrease in the age of initiating consumption of tobacco and alcohol is probably related to school context; that is, while Spanish students used to transfer to secondary school when they were 14 or 15 years old, now they do so when they are 11 or 12 (VA17). This change involves a rite of passage from being a young child to being an adolescent or young man/woman; such a change is closely associated with health-risk behaviours, especially consumption of tobacco and alcohol.

Based on the data from the experts and professionals interviewed, these individuals also perceived gender differences in the consumption of drugs. Not only the prevalence was different, the reasons, circumstances and meanings associated were different in boys and girls (VP1, VP2, and VP3). It was also seen that the frequency and intensity of consumption, as well as involvement in it, were different between the sexes (greater consumption of illegal drugs in boys and greater consumption of legal drugs in girls). These perceptions were backed up by both the surveys these specialists carried out in their entities and by their professional experience. Likewise, it was emphasised how the girls’ greater participation in legal drug consumption was related to the greater equality and social participation in all aspects of their environment, and to specific interpretations of what equality of the sexes meant.

Adolescents’ perception of the preventative campaigns and actionsThe lack of effectiveness of prevention campaigns was raised in all the groups (VA18). They considered the information and training that they received on drugs, which they called «chats» or «giving the sermon», to be ineffectual (VA19). Along with indicating this general evaluation, they mentioned 2 central ideas that should be taken into account when designing an intervention. The first one was that the more forbidden a behaviour was, the more attractive it was and, consequently, the more it was done (VA20). In second place, they pointed out the contradiction and incoherence adults, parents and teachers showed between what they said and what they did. The adolescents were not allowed to drink or smoke, and even the messages they received were about how these actions were prejudicial for your health, but these adults nevertheless did not act accordingly (VA21).

Need for the perspective of gender and its application in prevention programmesThe male and female professionals interviewed worked in universal or selective prevention and their responses were interpreted based on the intervention they carried out. Some of them raised the issue that, in the prevention indicated, applying the perspective of gender was essential and required for the success of the intervention and that this involved differential interventions (VP4). However, it was not so evident for other professionals that this question (so clearly proposed for the treatment of drug dependencies) was the same in universal or selective prevention. Those who worked in selective prevention suggested that such differentiation was not needed, indicating that because there was an individualised intervention (whether personal or in group), it was not necessary to include the perspective of gender (VP5). Others reported that the need had not come up for them; that is, they had not perceived that a differential intervention was necessary (VP6). Almost all of the professionals agreed that incorporating the gender perspective in intervention programmes was necessary (except for one of the experts interviewed). However, they all, both women and men, were unsure about–or did not know–how it should be included (VP7 and VP8).

The need for looking into this question in greater detail was posed, of investigating more and acquiring greater knowledge to know how to incorporate it in the preventative actions with the adolescents. The meaning that was associated with the perspective of gender seemed to involve differential action; that is, working boys and girls separately. However, this was an unclear point among the experts and professionals interviewed. The need to carry out actions focused on boys or on girls had not been seen either, nor had the request to do so been received, in spite of the fact that differences between sexes existed. One of the experts interviewed suggested that applying programmes aimed at each of the sexes separately would not yield good results, because they would be criticised from the start for the discrimination that they would cause (VP9). In other words, that the differential action would destroy the equality between the sexes and that, consequently, there would be a discrimination that would not be sustainable or accepted in a public health intervention. Although this discourse on equality between men and women is also shared by wide sectors of the general population and by the adolescents themselves, public health indicators still show significant gaps of inequality between the two sexes. This is especially true in cultural aspects, such as social images, the roles assigned to each gender and the values assigned to each. Consequently, indiscriminate preventative interventions not focused on the needs of gender, ethnic group, age and other society-structuring variables make preventing tobacco and alcohol consumption among young people ineffective. Over-zealous attention to equality may obscure the fact that the objective is not to eliminate differences, but to eliminate inequalities.

DiscussionGender differences in the consumption of drugs, especially tobacco and alcohol, were confirmed and perceived by the experts and the adolescents themselves. Our data validate and complement results obtained by quantitative strategies. The meanings of tobacco and alcohol consumption associated with the girls were different from those associated with the boys. A certain symbol of rebelliousness, easing stress and losing weight were some of the reasons and important meanings associated with the girls, which have been indicated in other international studies.13,14 A degree of hidden or private consumption by girls has also been mentioned,15 just as indicated in some of our female comments. On the other hand, smoking and drinking possess a positive social image among peer groups16,17; these behaviours are still not deviant or stigmatised as has been posed in certain adult contexts.18 Quite the contrary; this behaviour takes the form of a rite of passage to adult life19 and exercises a certain attraction because it is forbidden. The adolescents themselves confirmed, despite their scant life experience, that they had observed early initiation into tobacco and alcohol consumption in many of their classmates. As the adolescents themselves pointed out, a factor that very possibly contributed to this drop in the age of initiation in Spain (noticed in national student questionnaires) could be the change in educational context, that is, the transfer from primary to secondary school. The power of context and associated meanings, symbols and rites for adolescents explain many of their risk behaviours. Smoking is not only an individual act, but it is also a social one and a product of social interaction. The change to secondary school has important symbolic connotations for younger adolescents. Going to secondary school means being older, not being a little boy or little girl any longer, the same meaning that smoking and drinking have for both the sexes.

As some studies20,21 based on surveys administered to adolescent students indicate, our data also emphasise that physical activity and sport are related to the absence of or decrease in consumption of tobacco, and a possible explanation of the greater consumption of tobacco among the female adolescents might be that they participated less in sport, as the girls themselves indicated in their comments. This aspect should be taken into consideration in preventative actions. While physical activity and sport should be promoted for girls, it is enough to reinforce them for boys.

One of our research questions is difficult to answer based on the results achieved. Gender differences were confirmed and theoretically including the perspective of gender in prevention programmes is considered correct. However, how to do this is not known and there are even doubts about it. While interventions in the international context applying the perspective of gender have had various courses of action,10,14 the comments obtained from the Madrid experts and professionals interviewed indicate that the same is not true here. A possible explanation for the results obtained may be having assumed that the males and females interviewed knew the meaning of gender perspective (that is, they knew what it consisted of) and each of them attributed different conceptions and components to the term. That would explain why they reduced differential intervention in their comments to separating boys and girls in preventative activities, when this is just one of the possible options.10

It is necessary to put together preventative strategies that take the social meanings and image of drug consumption into account if the prevention is to be effective. Based on the adolescents’ comments, the model of student information about drugs should be reviewed. The need to include a gender perspective, as well as other categories such as cultural diversity and ethnicity,3,22,23 may be required at the present time to delay or prevent initiation into consumption of tobacco or alcohol. Individual, close relationships may possibly be more important than general, indiscriminate messages. The doctor-patient-adolescent relationship could be a source of information about and prevention of health problems. In spite of the fact that other studies24 have not found a relationship between consumption by parents and brothers or sisters and consumption by adolescents, the comments in this study indicate that these 2 factors are linked to a great degree, as other studies14 also indicate. The adolescents considered them to be important role models and criticised their incoherence.

Our study has a few limitations. First of all, it focuses on the Community of Madrid, so the meanings associated in other autonomous communities might be different. Furthermore, the design of the sample consisting of the discussion groups does not cover all the dimensions possible (rural/urban, very high or low social class, etc.). Neither are the groups composed of the younger boys and girls (1st year of the CSE). Lastly, although the comments collected may serve to illustrate general tendencies of adolescents and experts in prevention, they cannot be generalised to the entire autonomous community, much less to the national as a whole.

Our results highlight different meanings associated with the consumption of tobacco and alcohol among adolescent boys and girls and the need to include gender perspective to ensure that prevention actions are effective. We probably have not been able to translate the application of this perspective to preventative messages and interventions yet; this remains an issue that needs to be addressed in the future.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were carried out on human beings or on animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects to which the article refers. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThis study is part of the research project “Risk and Legality. Socio-cultural Factors that Facilitate the Use of Drugs Among Adolescent Women”. 2008–2010 Innovation and R&D Project of the Institute of Women, File no. 125/07; coordinated by the Universidad de Granada.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

We are grateful for the collaboration of the boys and girls that participated in the discussion groups. Likewise, we wish to thank the specialists and professionals for their participation and contributions, as well as their institutions for permitting them to perform the interview.

Please cite this article as: Meneses C, Charro B. ¿Es necesaria una intervención diferencial de género en la prevención universal y selectiva del consumo de drogas en adolescentes? Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2014;7:5–12.