International studies on clozapine use usually show lower than expected prescription proportions, under-dosing and delayed initiation of treatment, which has led to a number of initiatives aimed at improving its use and reducing the striking variability observed among practitioners. There are no similar studies on the Spanish population. Therefore we planned initial data collection from 4 territorial samples. We hypothesised that clozapine prescription would also be low and variable in our country. If this hypothesis were confirmed, a reflection on possible strategies would be necessary.

Material and methodsWe accessed data on clozapine prescription in Catalonia, Castile and Leon, the Basque Country and the Clinical Management Area of the Hospital 12 de Octubre (Madrid).

ResultsPatients diagnosed with schizophrenia under treatment in these territories comprise around .3% of their total population; treatment with clozapine ranges between 33.0 and 57.0 per 10,000 inhabitants; patients diagnosed with schizophrenia on current treatment with clozapine range between 13.7% and 18.6% of the total number of patients with this diagnosis. The coefficient of variation between centres and prescribers is often higher than 50%.

ConclusionsAlthough below the figures suggested as desirable in the literature, global prescribing data for clozapine in the areas we studied are not as low as the data collected in other international studies, and are in the range of countries in our environment. However, the variability in prescription is large and apparently not justified; this heterogeneity increases as we focus on smaller areas, and there is great heterogeneity at the level of individual prescription.

Los datos internacionales disponibles sobre uso de clozapina recogen en general una baja prescripción, infradosificación y retraso en el inicio del tratamiento, y han originado diversas iniciativas para mejorar su uso y disminuir la llamativa variabilidad. No disponemos de estudios que valoren estos aspectos en población española, por lo que nos hemos planteado una primera y modesta aproximación a través de 4 muestras territoriales. Nuestra hipótesis es que, al igual que las referencias comentadas, en nuestro país el consumo de clozapina podría ser bajo y variable. Nuestro objetivo, en caso de confirmarse la hipótesis, sería iniciar una reflexión sobre posibles estrategias a plantear.

Material y métodosLos autores han accedido a datos de consumo de clozapina en Cataluña, Castilla y León, País Vasco y un Área de Madrid (el Área de Gestión Clínica PSM del Hospital 12 de Octubre).

ResultadosLos pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia en tratamiento en los territorios estudiados oscilan en torno al 0,3%; los tratamientos con clozapina/10.000 habitantes entre el 33% y 57%; y los pacientes diagnosticados como esquizofrenia en tratamiento con clozapina suponen entre el 13,7% y 18,6% de los tratados. El coeficiente de variación entre centros y prescriptores es frecuentemente superior al 50%.

ConclusionesAunque por debajo de las cifras indicadas por la literatura, los datos globales de prescripción de clozapina en los territorios que hemos estudiado no son tan bajos como los recogidos en otros trabajos internacionales, y se sitúan en el rango de países de nuestro entorno. Sin embargo, la variabilidad en la prescripción es muy importante, aparentemente no justificada; y aumenta a medida que analizamos zonas menores, hasta una gran heterogeneidad de la prescripción individual.

Although conceptually challenged1 the psychotic syndrome which for a century we have being calling schizophrenia continues to be the paradigm of mental illness.2 Treatment with antipsychotic drugs (AP) partially helps to alleviate some of its symptoms and is considered a necessary part of more complex procedures.3 However these drugs are also prone to intense and prevalent reflection.4–7 The first generation of AP has been replaced by the so-called “atypical antipsychotics” (AA).8 Despite the fact the concept of being “atypical” is confusing, no difference in efficacy has been demonstrated,9–13 and the uniformity of the AA group is unsustainable14–18 New AP drugs have increased in consumption exponentially on the acceptance of new indications, or due to their off-label use.19,20

Clozapine was the first AP classified as “atypical”, based on its mechanism of action, which was a non-provoker of catalepsy in animal models, or of extrapyramidal effects in patients. These elements were mimicked in its design or at least in its marketing by the AA drugs that followed in its wake.

Global efficacy data on schizophrenia suggest the superiority of clozapine compared with other AP13,15,21–27; specifically compared with the first generation of these drugs,21,14 and in general with the rest of the so-called “atypical” antipsychotics.10,18,25,28–30 Readmittance rates with clozapine are low31–34 and adherence is higher than that of other AP,32,35,36 as is also cognitive performance, level of employment activity, independent living and voluntary treatment.37,25 Clozapine is particularly effective in some differentiated situations, such as risk of suicide in schizophrenia,38–42 aggression in psycosis43 and reduction in the consumption of toxic substances in patients who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia.44–46 It is also effective in bipolar disorder47,48 and in psychosis in patients with Parkinson's disease.49

The absence of the expected response to appropriately administered drugs over time and doses is currently called “resistant schizophrenia” and is observable in 18%–30% of cases.50–54 This concept is highly questionable for its simplification, which focuses on the so-called “positive symptoms” and does not consider grading in response levels,55–56 highly varied prevalence,5,58 resulting in very recent studies reminding us of the need for independent studies from the sector and finally with inclusion criteria and homogeneous assessment tools,59 particularly with regard to follow-up.14,60 In this type of situations, clozapine presents itself as clearly superior to other substances,10,24,28,51,54,61–64 with symptomatic response rates of around 60%–70%65 and is the only substance approved for this indication.53

In the present framework of open challenge to mass, indiscriminate and undefined use of AP,6,5 beyond the simplistic descriptive perspective of “resistance” the neurobiological substrate of which we follow without realising66 clozapine is proposed as an alternative4 in patients who do not respond to the standard D2 blocking of AP,67,68 or when they appear to drop in efficacy over time and mass use, possibly related to a situation of secondary hypersensitivity to a process of receptorial over-regulation.69,57,70

Clozapine is not risk-free, but this has to be appropriately brought into proportion. Rigorous haematological monitoring has meant that with a prevalence of agranulocytosis estimated to be 1.3%,71–73 the rate of mortality would be .1%–.3%. The rate of diabetic ketoacidosis varies between 1.2% and 3.1%, and gastrointestinal hypomotility is 4%. Interest in myocarditis is increasing, incidence rates between countries are imbalanced, with a worldwide mean of .02%–1%. In Australia it is 7%, no doubt due to the stricter monitoring.71,74,75 As a whole, clozapine could be associated with lower overall mortality compared with any other AP,76–78 always lower than the risk of death from schizophrenia.38

Consumption of clozapine is lower than predicted conceding its indications.79–81 Specifically, the proportion of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who receive clozapine is usually lower than the expected resistance percentages expressed79,82–88: 6.7% in Québec,80 10.2% in Denmark,89 12.7% in India, or 11% in Hong Kong90 as examples, rising to 23% in England and Wales.91,92 In general, usage rates of clozapine have increased over the past decade,90,93 and there has only been a drop in prescription in Colombia and in the population with pubic insurances in U.S.A.94 where, in 199986 6.1% of patients with this diagnosis received clozapine, 5.7% in 2006; 4.9% in 2007; 4.6% in 2008; and 4.3% in 2009.95 In 2014 the population of U.S.A. with private insurance policies was, together with Japan, the country with the lowest rates of prescription (14/100,000 inhabitants and .6/100,000 respectively). This opposite extreme to Finland (189.2/100,000) and New Zealand (116.3/100,000) is extraordinary.94

Clozapine prescription ranges between 1% and 2% of the total AP in many countries,96 but geographical variability is highly relevant. Thus in U.S.A the difference between states ranges from 2% in Louisiana to 15.6% in South Dakota.88,97 In Quebec, regional differences range between 3.9% and9%80 and in Great Britain, the raised variability between regions in the National Health System drastically dropped between 2000 and 2006, after definition of guides in this respect98 and the drop in prices.99 In a very recent international analysis, there was a 315 times factor difference between the countries studied.94

Protocols and guidelines regarding dose and indication criteria3,100–102 are systematically not complied with, delaying the beginning by a mean of 5 years,84,89,103–106 and 8.9 years in males.35,107 During this time the largest proportion of patients(68%35) received multiple AP and combinations despite the little evidence to sustain this practice,86,103 worsening the prognosis and increasing the risks.108 Prescription is not just low and late, it also appears to be arbitrary on occasions or conditioned by racial factors.109–111 Manuel et al. found in New York that, surprisingly, drug consumption is associated with a lower prescription of clozapine and coloured people and those of Hispanic descent receive it less than white people,112 This tendency is replicated throughout the U.S.A.88 Age and gender also condition access to the drug: young people and women globally receive lower prescriptions of clozapine than men aged between 40 and 59 years.94 Finally under-dosing is frequent,53 and not only in standard care, where doses are rarely customised using plasmatic levels, but also in trials which compare clozapine to other drugs.12,113 Unlike the succession of approvals of new indications for the other AA, the specific indications shown for clozapine, such as the risk of suicide, drug consumption or aggression, are not officially accepted.

As a whole, the available international data indicate general low prescription, under-dosing and delay in treatment initiation. There are no available studies to assess these aspects in the Spanish population and we therefore proposed an initial approach with 4 territorial samples. Our hypothesis was that, similar to the references already commented upon, the consumption of clozapine in Spain could also be low and variable. Should this hypothesis prove to be true, our aim was to stimulate reflection on possible strategies.

Material and methodsThe authors were able to gain access to consumption data regarding clozapine in Catalonia, Castile Leon, the Basque Country and an Area of Madrid (the Clinical Psychiatry and Mental Health Management Area of Hospital 12 de Octubre, AGCPSM H12O), with a higher detail level in the Basque Country and Madrid. Here, apart from consumption in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia during a temporary period, subterritories were able to be differentiated (provinces of the Basque Country, Mental health centres of Usera, Villaverde and Carabanchel) and even professionals in the last case. The source in the case of Catalonia was “Salut Mental i Addiccions Resum executiu 2015, Xarxa de Salut Mental de Catalunya”; in the Basque Country it was “The use of clozapine in el treatment of patients with schizophrenia in the CAV Project”; in Castile Leon and in Madrid the source were data from the AGCPSM H12O and the pharmacy service of these areas.

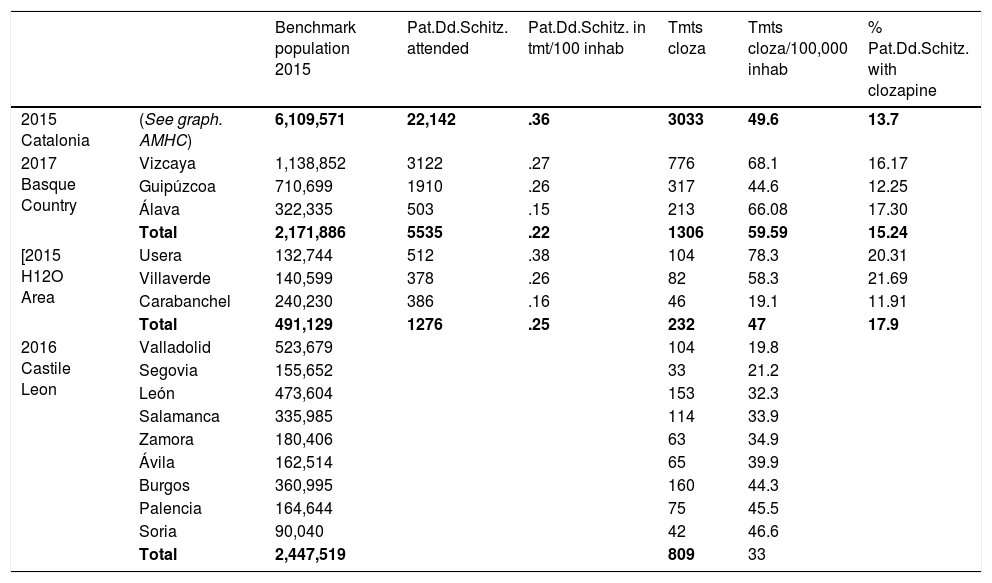

ResultsTable 1 shows the overall results.

Global results.

| Benchmark population 2015 | Pat.Dd.Schitz. attended | Pat.Dd.Schitz. in tmt/100 inhab | Tmts cloza | Tmts cloza/100,000 inhab | % Pat.Dd.Schitz. with clozapine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 Catalonia | (See graph. AMHC) | 6,109,571 | 22,142 | .36 | 3033 | 49.6 | 13.7 |

| 2017 Basque Country | Vizcaya | 1,138,852 | 3122 | .27 | 776 | 68.1 | 16.17 |

| Guipúzcoa | 710,699 | 1910 | .26 | 317 | 44.6 | 12.25 | |

| Álava | 322,335 | 503 | .15 | 213 | 66.08 | 17.30 | |

| Total | 2,171,886 | 5535 | .22 | 1306 | 59.59 | 15.24 | |

| [2015 H12O Area | Usera | 132,744 | 512 | .38 | 104 | 78.3 | 20.31 |

| Villaverde | 140,599 | 378 | .26 | 82 | 58.3 | 21.69 | |

| Carabanchel | 240,230 | 386 | .16 | 46 | 19.1 | 11.91 | |

| Total | 491,129 | 1276 | .25 | 232 | 47 | 17.9 | |

| 2016 Castile Leon | Valladolid | 523,679 | 104 | 19.8 | |||

| Segovia | 155,652 | 33 | 21.2 | ||||

| León | 473,604 | 153 | 32.3 | ||||

| Salamanca | 335,985 | 114 | 33.9 | ||||

| Zamora | 180,406 | 63 | 34.9 | ||||

| Ávila | 162,514 | 65 | 39.9 | ||||

| Burgos | 360,995 | 160 | 44.3 | ||||

| Palencia | 164,644 | 75 | 45.5 | ||||

| Soria | 90,040 | 42 | 46.6 | ||||

| Total | 2,447,519 | 809 | 33 |

AMHC: adult mental health centre, Catalonia; Pat.Dd.Schitz.: patients diagnosed with schizophrenia attended; Tmts cloza: treatments with clozapine.

Considering the population of reference in Catalonia in 2015 was 6,109,571 inhabitants, the rate of diagnosis of schizophrenia would amount to .36%; and the rate of treatment with clozapine to 4.9 per 10,000 inhabitants.

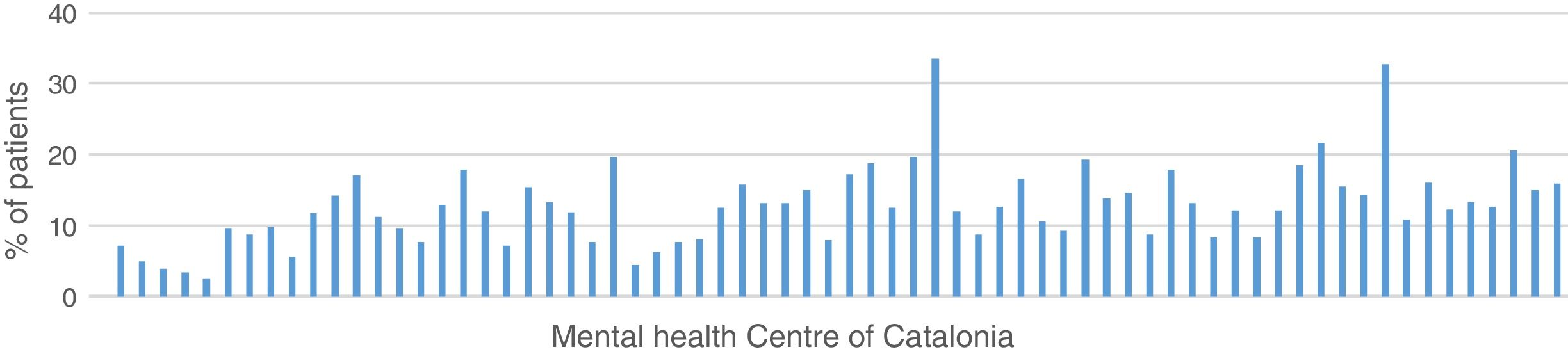

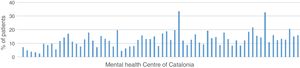

13.7% of the patients in treatment for a diagnosis of schizophrenia in Catalonia in 2015 received treatment with clozapine (11.6% women, 15% men), with a variation coefficient between centres above 50%, as reflected by the graph. This is a pharmaceutical prescription quality objective of the Mental Health Network of Catalonia (Fig. 1).

Basque CountryConsidering the population of the Basque Country in 2017 was 2,171,886 inhabitants, there were 5535 people in treatment diagnosed with schizophrenia, which amounts to .22% of the population (.26% in Guipúzcoa; .27% in Vizcaya and.15% in Álava).

In July 2017 there were 1306 patients in treatment with clozapine throughout the Basque Country, with no specified diagnoses. As a whole, the rate of treatments with clozapine in the autonomous community of the Basque Country would be 59.59/100,000 inhabitants, although their distribution was not uniform and the rate in Vizcaya was 68.1 treatments/100,000 inhabitants, in Guipúzcoa 44.6 and in Álava 66.08.

If we consider the patients in treatment diagnosed with schizophrenia and the number of treatments with clozapine, rates range between 12.25% of patients treated with this drug in Guipúzcoa, 17.30% in Álava, 16.17% in Vizcaya, with a mean of 15.24%.

Castile LeonWe only obtained the number of patients being treated with clozapine in each province in 2016, deducing the rate of treatments according to the population which, globally, was situated at 3.30/10,000 inhabitants, with some differences between provinces (from 1.98 in Valladolid to 4.66 in Scoria).

Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid AreaThe population attended in the whole of the H12O Madrid Area in 2015 was 491,129 inhabitants, 137,914 in Usera, 156,527 in Villaverde, and 196,688 in Carabanchel. Diagnostic rates for schizophrenia amounted to .25% (.37% in Usera; .24% in Villaverde; .19% in Carabanchel) and treatment rates with clozapine were 4.7/10,000 (5.9/10,000 in Usera; 5.2/10,000 in Villaverde; 2.3/10,000 in Carabanchel).

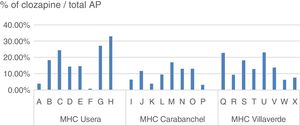

Seventeen point ninety seven per cent of patients in treatment after diagnosis of schizophrenia in the whole area received treatment with clozapine in 2015 (20.31% in Usera, 21.69% in Villaverde, and 11.1% in Carabanchel), as is reflected in Table 1.

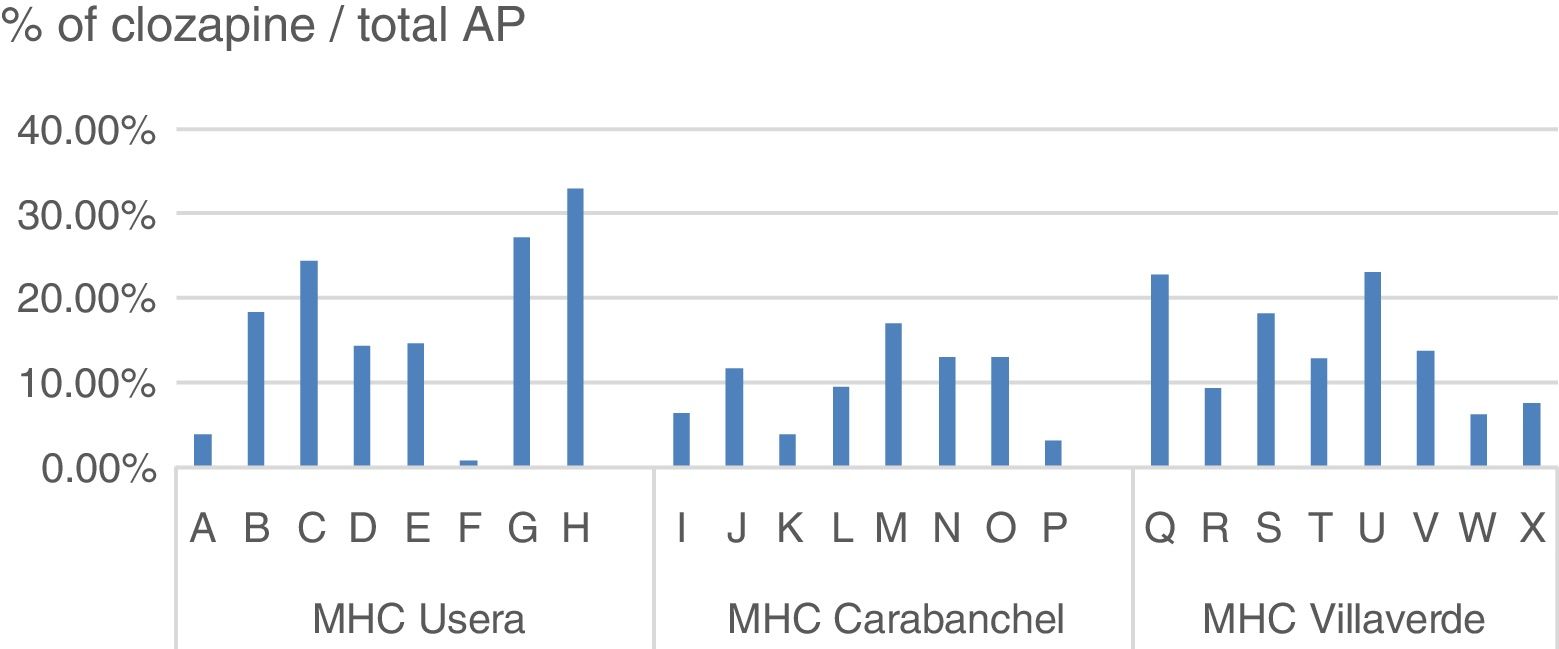

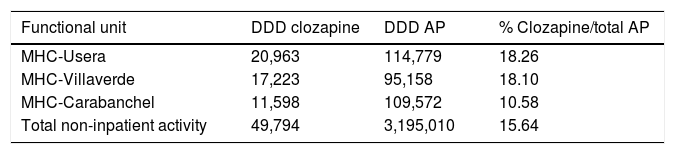

The daily defined dose (according to the Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology regulations) prescribed in 2015 in the H12O Area by the psychiatric specialists in the mental health centres (extra hospital treatment units which take on practically all the specialised follow-ups but do not include the primary care prescriptions), range between 10,239 and 20,963 in the districts mentioned, representing between 11.36% and 18.26% of the total AP indicated, as reflected in Table 2.

Daily defined dose of antipsychotics prescribed in mental health centres of the AGCPSM H12O.

| Functional unit | DDD clozapine | DDD AP | % Clozapine/total AP |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHC-Usera | 20,963 | 114,779 | 18.26 |

| MHC-Villaverde | 17,223 | 95,158 | 18.10 |

| MHC-Carabanchel | 11,598 | 109,572 | 10.58 |

| Total non-inpatient activity | 49,794 | 3,195,010 | 15.64 |

AGCPSM H12O: Clinical Psychiatry and Mental Health Management Area of Hospital 12 de Octubre; AP: antipsychotics; MHC: mental health centres; DDD: daily defined dose.

Within the same centre, the difference in prescription between specialists responsible for similar patient profiles was also notable (Fig. 2).

DiscussionOverall clozapine prescription data in the territories studied are not as low as those reflected in other international studies and they are similar to those in the range of neighbouring countries. However, the variability in prescription is highly pronounced and this increases as we analyse smaller areas, entailing great diversity of individual prescription.

As we mentioned between 18% and 30% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia will comply with the standard resistance criteria, and would be candidates for receiving clozapine. Of these 60%–70% would respond to the drug, and we should therefore find minimum rates of 20% of patients in treatment for this diagnosis, receiving clozapine.114

Although this minimum is not reached, overall data are close in H12O (17.9%); to a lower extent in the Basque Country (15.24%) and Catalonia (13.7%). These levels are above some of the countries referred to but very different from the British or the New Zealand data. However, these figures would vary notably when we observe the smaller territories: the 3 Basque Country provinces range between 17.30% in Álava, 16.17% in Vizcaya and 12.25% in Guipúzcoa; variations are very similar in the 3 districts of H12O: 21.69% in Villaverde, 20.31% in Usera, and 11.91% in Carabanchel. In Cataluña the differences between adult mental health centres ranged between .0% and 33.5%.

The notable variability between Spanish territories with no major socio-demographic differences, with a common usage guideline for clozapine and with a similar proportion of patients in treatment after diagnosis of schizophrenia (between .22% and .36% – lower than the theoretically expected prevalence of .5%–.7%115) is confirmed when, instead of patients in treatment, we study prescriptions. Overall, Spanish treatment rates with clozapine/100,000 inhabitants range between 33 and 59/100,000 inhabitants which are similar to countries such as France (43.1), Italy (41.8), Denmark (58k3) or Norway (50.1); but very different from New Zealand (116.3) or Holland (103.1); and very different from theoretical standards (200/100,000 inhabitants).94

However, as we analyse the prescriptions in smaller territories, variability increases, Thus, in Castile Leon the differences between provinces range from 19.8 to 46.6/100,000 inhabitants; in the Basque Country from 44.6 to 68.1/100,000 inhabitants. The proportion of clozapine treatments (daily defined doses) compared with the total AP which we found in the H12O districts ranged from 18.26% or 18.10% in Usera and Villaverde to 10.58% in Carabanchel. When we analysed prescription from different specialists, with similar consultation profiles and uniformity of population in number and quality, the differences between them rose to between .88% and 33.03% in the same centre.

Variability in practice is not exclusive to psychiatry,116,117 nor does it only affect drug prescription.118 On occasions, economic, social and cultural circumstances may condition that variability. We thus find the important change in the prescription of clozapine in England after the availability of cheaper generic drugs,99 or a drop in usage in China which although still high due to lower price and different usage regulations,119 is dropping in the most developed provinces and in families with a higher purchasing power level.120,121 In U.S.A. the use of clozapine in patients with private healthcare is low compared with the state system. This is probably due to the low number of patients who would be likely to be treated with clozapine, who work and therefore are able to have private healthcare.94 We believe in our case that although we have studied territories with undeniable sociocultural and economic differences, the weight of these factors is unable to explain the variability, and particularly if we observe that the highest differences are found in the smaller territories, such as the mental health centres for adults in Catalonia and even among prescribing practitioners of the same district in the case of H12O.

Although diversity does not explain our data, it is also striking in the regulations which govern the use of the drug in different countries, and which is proposed as the cause of the differences. Several factors are variable, including authorisation from the GP for prescribing it, availability of non-oral formulations, supply from normal pharmacies, maximum authorised dose, and the definition of “resistant” schizophrenia. Most of these differences do not have a clear clinical justification and there is a striking imbalance in access to the drug. However, although it seems probable that the restrictive regulations dissuade practitioners and patients from using the treatment, at least with regulations as extreme as those in Japan (which presents .6 treatments/100,000 inhabitants),94 there are no objective data regarding the effect of the different regulations in consumption,122 and it cannot be considered the essential factor, as illustrated in the case in Colombia, without restriction of usage by indications and without demand for haematological control, but with modest prescriptions.94

With regard to the general Spanish prescription framework, the AP market radically changed from the 1990s onwards, with the eruption of new drugs designed under its influence,55 without its risk,123 and which were initially believed to be as effective as clozapine. The new AP drugs have displaced the market of their predecessors despite their higher price,124–127 with aggressive marketing campaigns compared with the low economic interest in clozapine.88 These facts could partially account for prescription variability.111

Notwithstanding, although less defined than the previous factors those most frequently related to usage variability are as crude as that of the tradition in using a treatment in a certain territory, and the differences in criteria and knowledge of the prescribers.88,95 In the case of Spain, the relative social uniformity of the territories studied, the identity of a legal framework, and the increase in differences as we approach the prescriber's individual level leads us to believe that these are the factors with the most impact on our findings.

To date, few empirical research studies have been conducted on the reasons for underprescription of clozapine by psychiatrists.128 The arguments generally put forward are complications imposed by regulations, lack of expertise in management and fear of side effects by practitioners, patients or family members.129 The perception of risk in practitioners is disproportionate,114 and parallel to the lack of knowledge on usage.130,131

In recent years several different initiatives have been put into practice by the state bodies of several countries, which propose a use of clozapine adjusted to the patient volume which, with the appropriate risk–benefit balance, could benefit from treatment.95 These actions appear in the Clozapine Collaboration Group (DCCG), promoting a guide and other actions between professionals and patients. In 2014 a 56% increase in clozapine treatments had been achieved.114 In New Zealand between 2000 and 2004 the use of clozapine in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia increased from 21% to 32.8%.10,15,31 In 2010 the Best Practices Initiative—Clozapine was started in New York state. This developed facilitating actions for the prescribers and tools of assistance in the election for patients, in the framework of a shared decision model. New prescriptions increased by 40% between 2009 and 2013.132

The definition of a clear framework of knowledge is the necessary basis but is insufficient. Purely didactic approaches have little impact on the physician's behaviour,133 and it has been suggested that even the guidelines act as a further barrier.122 Actions need to be implemented at all healthcare levels, involving mental and general health teams, political actors and patients and family members28,134 with state support,135–137 using comprehensive care models with care support coordination systems for treatment implementation. The creation of specific devices131 is controversial. With regard to the law, despite being extraordinarily restrictive it is not complied with, and its solid grounding varies in different countries. An initiative needs to be generated to provide consistency to regulations122 and ensure their compliance.

It would be interesting to establish educational programmes for professionals, but also for patients and family members, provided this was within the framework of comprehensive care, shared decisions, care coordination and support for decision and implementation.131,138 To this end an initiative was developed in 2016 in the AGCPSM H12O, the aim of which was to promote appropriate use of clozapine. The initial stage, in keeping with this analysis of the prescription situation, consisted in the development of a practical usage guide for clozapine adapted to Spain, distributed through several actions among all Area professionals. A centralised, homogenous system was also organised for collection of accessible haematological protocols from any point in the network, including in the emergency unit. A second phase is to extend into primary care in a customised manner between patients and family members, with the use of specific material. The effects of these actions on prescription are to be studied.

LimitationsAs previously mentioned, this study was only intended as an initial action to motivate other broader and more uniform qualitative studies, and actions for correct prescription, should this be necessary. Although we consider that the main conclusions on global usage and variability are valid, the source of the data is multifarious in several aspects: the collection dates are different: Catalonia and the Basque Country collect prescription data in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia whilst although probably most prescriptions are for this diagnosis, the H12O does not specify this. Also, prescription data for the Basque Country and H12O refer to non-hospital activity. Catalonia offers us global data. Unlike the Basque Country, the prescription data from Catalonia and H12O refer to specialised care, without taking into account any prescriptions from in each territory. The data from Castile Leon only refer to prescriptions, with no consideration of diagnosis. We propose these differences be resolved in further, broader studies.

FundingThis study did not receive any public r private funding.

Conflict of interestsDr. Bernardo has been an adviser or has received fees or research funds from ABBiotics, Adamed, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Forum Pharmaceuticals, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, CIBERSAM, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Ministry of the Economy and Competitiveness, Ministry of Education Culture and Sport, 7th Framework Program of the European Union, Foundation Group for Research in Schizophrenia (EGRIS).

We would like to offer our thanks to Doctor Jiménez Arriero and Doctor Francisco Rivas for their help and drive in the coordination interests. Also to Doctor Oscar Pinar from the Pharmacy Service of the H12 de Octubre, and to Doctors Luis Agüera and Javier Rodríguez for their concerted efforts in data collection.

Please cite this article as: Sanz-Fuentenebro FJ, Uriarte Uriarte JJ, Bonet Dalmau P, Molina Rodriguez V, Bernardo Arroyo M. Patrón de uso de clozapina en España. Variabilidad e infraprescripción. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2018.02.005